Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lift (force)

View on Wikipedia

When a fluid flows around an object, the fluid exerts a force on the object. Lift is the component of this force that is perpendicular to the oncoming flow direction.[1] It contrasts with the drag force, which is the component of the force parallel to the flow direction. Lift conventionally acts in an upward direction in order to counter the force of gravity, but it may act in any direction perpendicular to the flow.

If the surrounding fluid is air, the force is called an aerodynamic force. In water or any other liquid, it is called a hydrodynamic force.

Dynamic lift is distinguished from other kinds of lift in fluids. Aerostatic lift or buoyancy, in which an internal fluid is lighter than the surrounding fluid, does not require movement and is used by balloons, blimps, dirigibles, boats, and submarines. Planing lift, in which only the lower portion of the body is immersed in a liquid flow, is used by motorboats, surfboards, windsurfers, sailboats, and water-skis.

Overview

[edit]

A fluid flowing around the surface of a solid object applies a force on it. It does not matter whether the object is moving through a stationary fluid (e.g. an aircraft flying through the air) or whether the object is stationary and the fluid is moving (e.g. a wing in a wind tunnel) or whether both are moving (e.g. a sailboat using the wind to move forward). Lift is the component of this force that is perpendicular to the oncoming flow direction.[1] Lift is always accompanied by a drag force, which is the component of the surface force parallel to the flow direction.

Lift is mostly associated with the wings of fixed-wing aircraft, although it is more widely generated by many other streamlined bodies such as propellers, kites, helicopter rotors, racing car wings, maritime sails, wind turbines, and by sailboat keels, ship's rudders, and hydrofoils in water. Lift is also used by flying and gliding animals, especially by birds, bats, and insects, and even in the plant world by the seeds of certain trees.[2] While the common meaning of the word "lift" assumes that lift opposes weight, lift can be in any direction with respect to gravity, since it is defined with respect to the direction of flow rather than to the direction of gravity. When an aircraft is cruising in straight and level flight, the lift opposes gravity. However, when an aircraft is climbing, descending, or banking in a turn the lift is tilted with respect to the vertical.[3] Lift may also act as downforce on the wing of a fixed-wing aircraft at the top of an aerobatic loop, and on the horizontal stabiliser of an aircraft. Lift may also be largely horizontal, for instance on a sailing ship.

The lift discussed in this article is mainly in relation to airfoils; marine hydrofoils and propellers share the same physical principles and work in the same way, despite differences between air and water such as density, compressibility, and viscosity.

The flow around a lifting airfoil is a fluid mechanics phenomenon that can be understood on essentially two levels: There are mathematical theories, which are based on established laws of physics and represent the flow accurately, but which require solving equations. And there are physical explanations without math, which are less rigorous.[4] Correctly explaining lift in these qualitative terms is difficult because the cause-and-effect relationships involved are subtle.[5] A comprehensive explanation that captures all of the essential aspects is necessarily complex. There are also many simplified explanations, but all leave significant parts of the phenomenon unexplained, while some also have elements that are simply incorrect.[4][6][7][8][9][10]

Simplified physical explanations of lift on an airfoil

[edit]

An airfoil is a streamlined shape that is capable of generating significantly more lift than drag.[11] A flat plate can generate lift, but not as much as a streamlined airfoil, and with somewhat higher drag. Most simplified explanations follow one of two basic approaches, based either on Newton's laws of motion or on Bernoulli's principle.[4][12][13][14]

Explanation based on flow deflection and Newton's laws

[edit]

An airfoil generates lift by exerting a downward force on the air as it flows past. According to Newton's third law, the air must exert an equal and opposite (upward) force on the airfoil, which is lift.[15][16][17][18]

As the airflow approaches the airfoil it is curving upward, but as it passes the airfoil it changes direction and follows a path that is curved downward. According to Newton's second law, this change in flow direction requires a downward force applied to the air by the airfoil. Then Newton's third law requires the air to exert an upward force on the airfoil; thus a reaction force, lift, is generated opposite to the directional change. In the case of an airplane wing, the wing exerts a downward force on the air and the air exerts an upward force on the wing.[19][20] The downward turning of the flow is not produced solely by the lower surface of the airfoil, and the air flow above the airfoil accounts for much of the downward-turning action.[21][22][23][24]

This explanation is correct but it is incomplete. It does not explain how the airfoil can impart downward turning to a much deeper swath of the flow than it actually touches. Furthermore, it does not mention that the lift force is exerted by pressure differences, and does not explain how those pressure differences are sustained.[4]

Controversy regarding the Coandă effect

[edit]Some versions of the flow-deflection explanation of lift cite the Coandă effect as the reason the flow is able to follow the convex upper surface of the airfoil. The conventional definition in the aerodynamics field is that the Coandă effect refers to the tendency of a fluid jet to stay attached to an adjacent surface that curves away from the flow, and the resultant entrainment of ambient air into the flow.[25][26][27]

More broadly, some consider the effect to include the tendency of any fluid boundary layer to adhere to a curved surface, not just the boundary layer accompanying a fluid jet. It is in this broader sense that the Coandă effect is used by some popular references to explain why airflow remains attached to the top side of an airfoil.[28][29] This is a controversial use of the term "Coandă effect"; the flow following the upper surface simply reflects an absence of boundary-layer separation, thus it is not an example of the Coandă effect.[30][31][32][33] Regardless of whether this broader definition of the "Coandă effect" is applicable, calling it the "Coandă effect" does not provide an explanation, it just gives the phenomenon a name.[34]

The ability of a fluid flow to follow a curved path is not dependent on shear forces, viscosity of the fluid, or the presence of a boundary layer. Air flowing around an airfoil, adhering to both upper and lower surfaces, and generating lift, is accepted as a phenomenon in inviscid flow.[35]

Explanations based on an increase in flow speed and Bernoulli's principle

[edit]There are two common versions of this explanation, one based on "equal transit time", and one based on "obstruction" of the airflow.

False explanation based on equal transit-time

[edit]The "equal transit time" explanation starts by arguing that the flow over the upper surface is faster than the flow over the lower surface because the path length over the upper surface is longer and must be traversed in equal transit time.[36][37][38] Bernoulli's principle states that under certain conditions increased flow speed is associated with reduced pressure. It is concluded that the reduced pressure over the upper surface results in upward lift.[39]

While it is true that the flow speeds up, a serious flaw in this explanation is that it does not correctly explain what causes the flow to speed up.[4] The longer-path-length explanation is incorrect. No difference in path length is needed, and even when there is a difference, it is typically much too small to explain the observed speed difference.[40] This is because the assumption of equal transit time is wrong when applied to a body generating lift. There is no physical principle that requires equal transit time in all situations and experimental results confirm that for a body generating lift the transit times are not equal.[41][42][43][44][45][46] In fact, the air moving past the top of an airfoil generating lift moves much faster than equal transit time predicts.[47] The much higher flow speed over the upper surface can be clearly seen in this animated flow visualization.

Obstruction of the airflow

[edit]

Like the equal transit time explanation, the "obstruction" or "streamtube pinching" explanation argues that the flow over the upper surface is faster than the flow over the lower surface, but gives a different reason for the difference in speed. It argues that the curved upper surface acts as more of an obstacle to the flow, forcing the streamlines to pinch closer together, making the streamtubes narrower. When streamtubes become narrower, conservation of mass requires that flow speed must increase.[48] Reduced upper-surface pressure and upward lift follow from the higher speed by Bernoulli's principle, just as in the equal transit time explanation. Sometimes an analogy is made to a venturi nozzle, claiming the upper surface of the wing acts like a venturi nozzle to constrict the flow.[49]

One serious flaw in the obstruction explanation is that it does not explain how streamtube pinching comes about, or why it is greater over the upper surface than the lower surface. For conventional wings that are flat on the bottom and curved on top this makes some intuitive sense, but it does not explain how flat plates, symmetric airfoils, sailboat sails, or conventional airfoils flying upside down can generate lift, and attempts to calculate lift based on the amount of constriction or obstruction do not predict experimental results.[50][51][52][53] Another flaw is that conservation of mass is not a satisfying physical reason why the flow would speed up. Effectively explaining the acceleration of an object requires identifying the force that accelerates it.[54]

Issues common to both versions of the Bernoulli-based explanation

[edit]A serious flaw common to all the Bernoulli-based explanations is that they imply that a speed difference can arise from causes other than a pressure difference, and that the speed difference then leads to a pressure difference, by Bernoulli's principle. This implied one-way causation is a misconception. The real relationship between pressure and flow speed is a mutual interaction.[4] As explained below under a more comprehensive physical explanation, producing a lift force requires maintaining pressure differences in both the vertical and horizontal directions. The Bernoulli-only explanations do not explain how the pressure differences in the vertical direction are sustained. That is, they leave out the flow-deflection part of the interaction.[4]

Although the two simple Bernoulli-based explanations above are incorrect, there is nothing incorrect about Bernoulli's principle or the fact that the air goes faster on the top of the wing, and Bernoulli's principle can be used correctly as part of a more complicated explanation of lift.[55]

Basic attributes of lift

[edit]Lift is a result of pressure differences and depends on angle of attack, airfoil shape, air density, and airspeed.

Pressure differences

[edit]Pressure is the normal force per unit area exerted by the air on itself and on surfaces that it touches. The lift force is transmitted through the pressure, which acts perpendicular to the surface of the airfoil. Thus, the net force manifests itself as pressure differences. The direction of the net force implies that the average pressure on the upper surface of the airfoil is lower than the average pressure on the underside.[56]

These pressure differences arise in conjunction with the curved airflow. When a fluid follows a curved path, there is a pressure gradient perpendicular to the flow direction with higher pressure on the outside of the curve and lower pressure on the inside.[57] This direct relationship between curved streamlines and pressure differences, sometimes called the streamline curvature theorem, was derived from Newton's second law by Leonhard Euler in 1754:

The left side of this equation represents the pressure difference perpendicular to the fluid flow. On the right side of the equation, ρ is the density, v is the velocity, and R is the radius of curvature. This formula shows that higher velocities and tighter curvatures create larger pressure differentials and that for straight flow (R → ∞), the pressure difference is zero.[58]

Angle of attack

[edit]

The angle of attack is the angle between the chord line of an airfoil and the oncoming airflow. A symmetrical airfoil generates zero lift at zero angle of attack. But as the angle of attack increases, the air is deflected through a larger angle and the vertical component of the airstream velocity increases, resulting in more lift. For small angles, a symmetrical airfoil generates a lift force roughly proportional to the angle of attack.[59][60]

As the angle of attack increases, the lift reaches a maximum at some angle; increasing the angle of attack beyond this critical angle of attack causes the upper-surface flow to separate from the wing; there is less deflection downward so the airfoil generates less lift. The airfoil is said to be stalled.[61]

Airfoil shape

[edit]

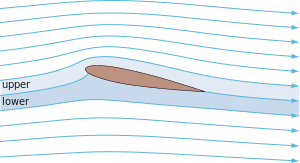

The maximum lift force that can be generated by an airfoil at a given airspeed depends on the shape of the airfoil, especially the amount of camber (curvature such that the upper surface is more convex than the lower surface, as illustrated at right). Increasing the camber generally increases the maximum lift at a given airspeed.[62][63]

Cambered airfoils generate lift at zero angle of attack. When the chord line is horizontal, the trailing edge has a downward direction and since the air follows the trailing edge it is deflected downward.[64] When a cambered airfoil is upside down, the angle of attack can be adjusted so that the lift force is upward. This explains how a plane can fly upside down.[65][66]

Flow conditions

[edit]The ambient flow conditions which affect lift include the fluid density, viscosity and speed of flow. Density is affected by temperature, and by the medium's acoustic velocity – i.e. by compressibility effects.

Air speed and density

[edit]Lift is proportional to the density of the air and approximately proportional to the square of the flow speed. Lift also depends on the size of the wing, being generally proportional to the wing's area projected in the lift direction. In calculations it is convenient to quantify lift in terms of a lift coefficient based on these factors.

Boundary layer and profile drag

[edit]No matter how smooth the surface of an airfoil seems, any surface is rough on the scale of air molecules. Air molecules flying into the surface bounce off the rough surface in random directions relative to their original velocities. The result is that when the air is viewed as a continuous material, it is seen to be unable to slide along the surface, and the air's velocity relative to the airfoil decreases to nearly zero at the surface (i.e., the air molecules "stick" to the surface instead of sliding along it), something known as the no-slip condition.[67] Because the air at the surface has near-zero velocity but the air away from the surface is moving, there is a thin boundary layer in which air close to the surface is subjected to a shearing motion.[68][69] The air's viscosity resists the shearing, giving rise to a shear stress at the airfoil's surface called skin friction drag. Over most of the surface of most airfoils, the boundary layer is naturally turbulent, which increases skin friction drag.[69][70]

Under usual flight conditions, the boundary layer remains attached to both the upper and lower surfaces all the way to the trailing edge, and its effect on the rest of the flow is modest. Compared to the predictions of inviscid flow theory, in which there is no boundary layer, the attached boundary layer reduces the lift by a modest amount and modifies the pressure distribution somewhat, which results in a viscosity-related pressure drag over and above the skin friction drag. The total of the skin friction drag and the viscosity-related pressure drag is usually called the profile drag.[70][71]

Stalling

[edit]

An airfoil's maximum lift at a given airspeed is limited by boundary-layer separation. As the angle of attack is increased, a point is reached where the boundary layer can no longer remain attached to the upper surface. When the boundary layer separates, it leaves a region of recirculating flow above the upper surface, as illustrated in the flow-visualization photo at right. This is known as the stall, or stalling. At angles of attack above the stall, lift is significantly reduced, though it does not drop to zero. The maximum lift that can be achieved before stall, in terms of the lift coefficient, is generally less than 1.5 for single-element airfoils and can be more than 3.0 for airfoils with high-lift slotted flaps and leading-edge devices deployed.[72]

Bluff bodies

[edit]The flow around bluff bodies – i.e. without a streamlined shape, or stalling airfoils – may also generate lift, in addition to a strong drag force. This lift may be steady, or it may oscillate due to vortex shedding. Interaction of the object's flexibility with the vortex shedding may enhance the effects of fluctuating lift and cause vortex-induced vibrations.[73] For instance, the flow around a circular cylinder generates a Kármán vortex street: vortices being shed in an alternating fashion from the cylinder's sides. The oscillatory nature of the flow produces a fluctuating lift force on the cylinder, even though the net (mean) force is negligible. The lift force frequency is characterised by the dimensionless Strouhal number, which depends on the Reynolds number of the flow.[74][75]

For a flexible structure, this oscillatory lift force may induce vortex-induced vibrations. Under certain conditions – for instance resonance or strong spanwise correlation of the lift force – the resulting motion of the structure due to the lift fluctuations may be strongly enhanced. Such vibrations may pose problems and threaten collapse in tall man-made structures like industrial chimneys.[73]

In the Magnus effect, a lift force is generated by a spinning cylinder in a freestream. Here the mechanical rotation acts on the boundary layer, causing it to separate at different locations on the two sides of the cylinder. The asymmetric separation changes the effective shape of the cylinder as far as the flow is concerned such that the cylinder acts like a lifting airfoil with circulation in the outer flow.[76]

A more comprehensive physical explanation

[edit]As described above under "Simplified physical explanations of lift on an airfoil", there are two main popular explanations: one based on downward deflection of the flow (Newton's laws), and one based on pressure differences accompanied by changes in flow speed (Bernoulli's principle). Either of these, by itself, correctly identifies some aspects of the lifting flow but leaves other important aspects of the phenomenon unexplained. A more comprehensive explanation involves both downward deflection and pressure differences (including changes in flow speed associated with the pressure differences), and requires looking at the flow in more detail.[77]

Lift at the airfoil surface

[edit]The airfoil shape and angle of attack work together so that the airfoil exerts a downward force on the air as it flows past. According to Newton's third law, the air must then exert an equal and opposite (upward) force on the airfoil, which is the lift.[17]

The net force exerted by the air occurs as a pressure difference over the airfoil's surfaces.[78] Pressure in a fluid is always positive in an absolute sense,[79] so that pressure must always be thought of as pushing, and never as pulling. The pressure thus pushes inward on the airfoil everywhere on both the upper and lower surfaces. The flowing air reacts to the presence of the wing by reducing the pressure on the wing's upper surface and increasing the pressure on the lower surface. The pressure on the lower surface pushes up harder than the reduced pressure on the upper surface pushes down, and the net result is upward lift.[78]

The pressure difference which results in lift acts directly on the airfoil surfaces; however, understanding how the pressure difference is produced requires understanding what the flow does over a wider area.

The wider flow around the airfoil

[edit]

An airfoil affects the speed and direction of the flow over a wide area, producing a pattern called a velocity field. When an airfoil produces lift, the flow ahead of the airfoil is deflected upward, the flow above and below the airfoil is deflected downward leaving the air far behind the airfoil in the same state as the oncoming flow far ahead. The flow above the upper surface is sped up, while the flow below the airfoil is slowed down. Together with the upward deflection of air in front and the downward deflection of the air immediately behind, this establishes a net circulatory component of the flow. The downward deflection and the changes in flow speed are pronounced and extend over a wide area, as can be seen in the flow animation on the right. These differences in the direction and speed of the flow are greatest close to the airfoil and decrease gradually far above and below. All of these features of the velocity field also appear in theoretical models for lifting flows.[80][81]

The pressure is also affected over a wide area, in a pattern of non-uniform pressure called a pressure field. When an airfoil produces lift, there is a diffuse region of low pressure above the airfoil, and usually a diffuse region of high pressure below, as illustrated by the isobars (curves of constant pressure) in the drawing. The pressure difference that acts on the surface is just part of this pressure field.[82]

Mutual interaction of pressure differences and changes in flow velocity

[edit]

The non-uniform pressure exerts forces on the air in the direction from higher pressure to lower pressure. The direction of the force is different at different locations around the airfoil, as indicated by the block arrows in the pressure field around an airfoil figure. Air above the airfoil is pushed toward the center of the low-pressure region, and air below the airfoil is pushed outward from the center of the high-pressure region.

According to Newton's second law, a force causes air to accelerate in the direction of the force. Thus the vertical arrows in the accompanying pressure field diagram indicate that air above and below the airfoil is accelerated, or turned downward, and that the non-uniform pressure is thus the cause of the downward deflection of the flow visible in the flow animation. To produce this downward turning, the airfoil must have a positive angle of attack or have sufficient positive camber. Note that the downward turning of the flow over the upper surface is the result of the air being pushed downward by higher pressure above it than below it. Some explanations that refer to the "Coandă effect" suggest that viscosity plays a key role in the downward turning, but this is false. (see above under "Controversy regarding the Coandă effect").

The arrows ahead of the airfoil indicate that the flow ahead of the airfoil is deflected upward, and the arrows behind the airfoil indicate that the flow behind is deflected upward again, after being deflected downward over the airfoil. These deflections are also visible in the flow animation.

The arrows ahead of the airfoil and behind also indicate that air passing through the low-pressure region above the airfoil is sped up as it enters, and slowed back down as it leaves. Air passing through the high-pressure region below the airfoil is slowed down as it enters and then sped back up as it leaves. Thus the non-uniform pressure is also the cause of the changes in flow speed visible in the flow animation. The changes in flow speed are consistent with Bernoulli's principle, which states that in a steady flow without viscosity, lower pressure means higher speed, and higher pressure means lower speed.

Thus changes in flow direction and speed are directly caused by the non-uniform pressure. But this cause-and-effect relationship is not just one-way; it works in both directions simultaneously. The air's motion is affected by the pressure differences, but the existence of the pressure differences depends on the air's motion. The relationship is thus a mutual, or reciprocal, interaction: Air flow changes speed or direction in response to pressure differences, and the pressure differences are sustained by the air's resistance to changing speed or direction.[83] A pressure difference can exist only if something is there for it to push against. In aerodynamic flow, the pressure difference pushes against the air's inertia, as the air is accelerated by the pressure difference.[84] This is why the air's mass is part of the calculation, and why lift depends on air density.

Sustaining the pressure difference that exerts the lift force on the airfoil surfaces requires sustaining a pattern of non-uniform pressure in a wide area around the airfoil. This requires maintaining pressure differences in both the vertical and horizontal directions, and thus requires both downward turning of the flow and changes in flow speed according to Bernoulli's principle. The pressure differences and the changes in flow direction and speed sustain each other in a mutual interaction. The pressure differences follow naturally from Newton's second law and from the fact that flow along the surface follows the predominantly downward-sloping contours of the airfoil. And the fact that the air has mass is crucial to the interaction.[85]

How simpler explanations fall short

[edit]Producing a lift force requires both downward turning of the flow and changes in flow speed consistent with Bernoulli's principle. Each of the simplified explanations given above in Simplified physical explanations of lift on an airfoil falls short by trying to explain lift in terms of only one or the other, thus explaining only part of the phenomenon and leaving other parts unexplained.[86]

Quantifying lift

[edit]Pressure integration

[edit]When the pressure distribution on the airfoil surface is known, determining the total lift requires adding up the contributions to the pressure force from local elements of the surface, each with its own local value of pressure. The total lift is thus the integral of the pressure, in the direction perpendicular to the farfield flow, over the airfoil surface.[87]

where:

- S is the projected (planform) area of the airfoil, measured normal to the mean airflow;

- n is the normal unit vector pointing into the wing;

- k is the vertical unit vector, normal to the freestream direction.

The above lift equation neglects the skin friction forces, which are small compared to the pressure forces.

By using the streamwise vector i parallel to the freestream in place of k in the integral, we obtain an expression for the pressure drag Dp (which includes the pressure portion of the profile drag and, if the wing is three-dimensional, the induced drag). If we use the spanwise vector j, we obtain the side force Y.

The validity of this integration generally requires the airfoil shape to be a closed curve that is piecewise smooth.

Lift coefficient

[edit]Lift depends on the size of the wing, being approximately proportional to the wing area. It is often convenient to quantify the lift of a given airfoil by its lift coefficient , which defines its overall lift in terms of a unit area of the wing.

If the value of for a wing at a specified angle of attack is given, then the lift produced for specific flow conditions can be determined:[88]

where

- is the lift force

- is the air density

- is the velocity or true airspeed

- is the planform (projected) wing area

- is the lift coefficient at the desired angle of attack, Mach number, and Reynolds number[89]

Mathematical theories of lift

[edit]Mathematical theories of lift are based on continuum fluid mechanics, assuming that air flows as a continuous fluid.[90][91][92] Lift is generated in accordance with the fundamental principles of physics, the most relevant being the following three principles:[93]

- Conservation of momentum, which is a consequence of Newton's laws of motion, especially Newton's second law (which relates the net force on an element of air to its rate of momentum change) and third law.

- Conservation of mass, including the assumption that the airfoil's surface is impermeable for the air flowing around, and

- Conservation of energy, which says that energy is neither created nor destroyed.

Because an airfoil affects the flow in a wide area around it, the conservation laws of mechanics are embodied in the form of partial differential equations combined with a set of boundary condition requirements which the flow has to satisfy at the airfoil surface and far away from the airfoil.[94]

To predict lift requires solving the equations for a particular airfoil shape and flow condition, which generally requires calculations that are so voluminous that they are practical only on a computer, through the methods of computational fluid dynamics (CFD). Determining the net aerodynamic force from a CFD solution requires "adding up" (integrating) the forces due to pressure and shear determined by the CFD over every surface element of the airfoil as described under "pressure integration".

The Navier–Stokes equations (NS) provide the potentially most accurate theory of lift, but in practice, capturing the effects of turbulence in the boundary layer on the airfoil surface requires sacrificing some accuracy, and requires use of the Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes equations (RANS). Simpler but less accurate theories have also been developed.

Navier–Stokes (NS) equations

[edit]These equations represent conservation of mass, Newton's second law (conservation of momentum), conservation of energy, the Newtonian law for the action of viscosity, the Fourier heat conduction law, an equation of state relating density, temperature, and pressure, and formulas for the viscosity and thermal conductivity of the fluid.[95][96]

In principle, the NS equations, combined with boundary conditions of no through-flow and no slip at the airfoil surface, could be used to predict lift with high accuracy in any situation in ordinary atmospheric flight. However, airflows in practical situations always involve turbulence in the boundary layer next to the airfoil surface, at least over the aft portion of the airfoil. Predicting lift by solving the NS equations in their raw form would require the calculations to resolve the details of the turbulence, down to the smallest eddy. This is not yet possible, even on the most powerful computer.[97] So in principle the NS equations provide a complete and very accurate theory of lift, but practical prediction of lift requires that the effects of turbulence be modeled in the RANS equations rather than computed directly.

Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equations

[edit]These are the NS equations with the turbulence motions averaged over time, and the effects of the turbulence on the time-averaged flow represented by turbulence modeling (an additional set of equations based on a combination of dimensional analysis and empirical information on how turbulence affects a boundary layer in a time-averaged average sense).[98][99] A RANS solution consists of the time-averaged velocity vector, pressure, density, and temperature defined at a dense grid of points surrounding the airfoil.

The amount of computation required is a minuscule fraction (billionths)[97] of what would be required to resolve all of the turbulence motions in a raw NS calculation, and with large computers available it is now practical to carry out RANS calculations for complete airplanes in three dimensions. Because turbulence models are not perfect, the accuracy of RANS calculations is imperfect, but it is adequate for practical aircraft design. Lift predicted by RANS is usually within a few percent of the actual lift.

Inviscid-flow equations (Euler or potential)

[edit]The Euler equations are the NS equations without the viscosity, heat conduction, and turbulence effects.[100] As with a RANS solution, an Euler solution consists of the velocity vector, pressure, density, and temperature defined at a dense grid of points surrounding the airfoil. While the Euler equations are simpler than the NS equations, they do not lend themselves to exact analytic solutions.

Further simplification is available through potential flow theory, which reduces the number of unknowns to be determined, and makes analytic solutions possible in some cases, as described below.

Either Euler or potential-flow calculations predict the pressure distribution on the airfoil surfaces roughly correctly for angles of attack below stall, where they might miss the total lift by as much as 10–20%. At angles of attack above stall, inviscid calculations do not predict that stall has happened, and as a result they grossly overestimate the lift.

In potential-flow theory, the flow is assumed to be irrotational, i.e. that small fluid parcels have no net rate of rotation. Mathematically, this is expressed by the statement that the curl of the velocity vector field is everywhere equal to zero. Irrotational flows have the convenient property that the velocity can be expressed as the gradient of a scalar function called a potential. A flow represented in this way is called potential flow.[101][102][103][104]

In potential-flow theory, the flow is assumed to be incompressible. Incompressible potential-flow theory has the advantage that the equation (Laplace's equation) to be solved for the potential is linear, which allows solutions to be constructed by superposition of other known solutions. The incompressible-potential-flow equation can also be solved by conformal mapping, a method based on the theory of functions of a complex variable. In the early 20th century, before computers were available, conformal mapping was used to generate solutions to the incompressible potential-flow equation for a class of idealized airfoil shapes, providing some of the first practical theoretical predictions of the pressure distribution on a lifting airfoil.

A solution of the potential equation directly determines only the velocity field. The pressure field is deduced from the velocity field through Bernoulli's equation.

Applying potential-flow theory to a lifting flow requires special treatment and an additional assumption. The problem arises because lift on an airfoil in inviscid flow requires circulation in the flow around the airfoil (See "Circulation and the Kutta–Joukowski theorem" below), but a single potential function that is continuous throughout the domain around the airfoil cannot represent a flow with nonzero circulation. The solution to this problem is to introduce a branch cut, a curve or line from some point on the airfoil surface out to infinite distance, and to allow a jump in the value of the potential across the cut. The jump in the potential imposes circulation in the flow equal to the potential jump and thus allows nonzero circulation to be represented. However, the potential jump is a free parameter that is not determined by the potential equation or the other boundary conditions, and the solution is thus indeterminate. A potential-flow solution exists for any value of the circulation and any value of the lift. One way to resolve this indeterminacy is to impose the Kutta condition,[105][106] which is that, of all the possible solutions, the physically reasonable solution is the one in which the flow leaves the trailing edge smoothly. The streamline sketches illustrate one flow pattern with zero lift, in which the flow goes around the trailing edge and leaves the upper surface ahead of the trailing edge, and another flow pattern with positive lift, in which the flow leaves smoothly at the trailing edge in accordance with the Kutta condition.

Linearized potential flow

[edit]This is potential-flow theory with the further assumptions that the airfoil is very thin and the angle of attack is small.[107] The linearized theory predicts the general character of the airfoil pressure distribution and how it is influenced by airfoil shape and angle of attack, but is not accurate enough for design work. For a 2D airfoil, such calculations can be done in a fraction of a second in a spreadsheet on a PC.

Circulation and the Kutta–Joukowski theorem

[edit]

When an airfoil generates lift, several components of the overall velocity field contribute to a net circulation of air around it: the upward flow ahead of the airfoil, the accelerated flow above, the decelerated flow below, and the downward flow behind.

The circulation can be understood as the total amount of "spinning" (or vorticity) of an inviscid fluid around the airfoil.

The Kutta–Joukowski theorem relates the lift per unit width of span of a two-dimensional airfoil to this circulation component of the flow.[80][108][109] It is a key element in an explanation of lift that follows the development of the flow around an airfoil as the airfoil starts its motion from rest and a starting vortex is formed and left behind, leading to the formation of circulation around the airfoil.[110][111][112] Lift is then inferred from the Kutta-Joukowski theorem. This explanation is largely mathematical, and its general progression is based on logical inference, not physical cause-and-effect.[113]

The Kutta–Joukowski model does not predict how much circulation or lift a two-dimensional airfoil produces. Calculating the lift per unit span using Kutta–Joukowski requires a known value for the circulation. In particular, if the Kutta condition is met, in which the rear stagnation point moves to the airfoil trailing edge and attaches there for the duration of flight, the lift can be calculated theoretically through the conformal mapping method.

The lift generated by a conventional airfoil is dictated by both its design and the flight conditions, such as forward velocity, angle of attack and air density. Lift can be increased by artificially increasing the circulation, for example by boundary-layer blowing or the use of blown flaps. In the Flettner rotor the entire airfoil is circular and spins about a spanwise axis to create the circulation.

Three-dimensional flow

[edit]

The flow around a three-dimensional wing involves significant additional issues, especially relating to the wing tips. For a wing of low aspect ratio, such as a typical delta wing, two-dimensional theories may provide a poor model and three-dimensional flow effects can dominate.[114] Even for wings of high aspect ratio, the three-dimensional effects associated with finite span can affect the whole span, not just close to the tips.

Wing tips and spanwise distribution

[edit]The vertical pressure gradient at the wing tips causes air to flow sideways, out from under the wing then up and back over the upper surface. This reduces the pressure gradient at the wing tip, therefore also reducing lift. The lift tends to decrease in the spanwise direction from root to tip, and the pressure distributions around the airfoil sections change accordingly in the spanwise direction. Pressure distributions in planes perpendicular to the flight direction tend to look like the illustration at right.[115] This spanwise-varying pressure distribution is sustained by a mutual interaction with the velocity field. Flow below the wing is accelerated outboard, flow outboard of the tips is accelerated upward, and flow above the wing is accelerated inboard, which results in the flow pattern illustrated at right.[116]

There is more downward turning of the flow than there would be in a two-dimensional flow with the same airfoil shape and sectional lift, and a higher sectional angle of attack is required to achieve the same lift compared to a two-dimensional flow.[117] The wing is effectively flying in a downdraft of its own making, as if the freestream flow were tilted downward, with the result that the total aerodynamic force vector is tilted backward slightly compared to what it would be in two dimensions. The additional backward component of the force vector is called lift-induced drag.

The difference in the spanwise component of velocity above and below the wing (between being in the inboard direction above and in the outboard direction below) persists at the trailing edge and into the wake downstream. After the flow leaves the trailing edge, this difference in velocity takes place across a relatively thin shear layer called a vortex sheet.

Horseshoe vortex system

[edit]

The wingtip flow leaving the wing creates a tip vortex. As the main vortex sheet passes downstream from the trailing edge, it rolls up at its outer edges, merging with the tip vortices. The combination of the wingtip vortices and the vortex sheets feeding them is called the vortex wake.

In addition to the vorticity in the trailing vortex wake there is vorticity in the wing's boundary layer, called 'bound vorticity', which connects the trailing sheets from the two sides of the wing into a vortex system in the general form of a horseshoe. The horseshoe form of the vortex system was recognized by the British aeronautical pioneer Lanchester in 1907.[118]

Given the distribution of bound vorticity and the vorticity in the wake, the Biot–Savart law (a vector-calculus relation) can be used to calculate the velocity perturbation anywhere in the field, caused by the lift on the wing. Approximate theories for the lift distribution and lift-induced drag of three-dimensional wings are based on such analysis applied to the wing's horseshoe vortex system.[119][120] In these theories, the bound vorticity is usually idealized and assumed to reside at the camber surface inside the wing.

Because the velocity is deduced from the vorticity in such theories, some authors describe the situation to imply that the vorticity is the cause of the velocity perturbations, using terms such as "the velocity induced by the vortex", for example.[121] But attributing mechanical cause-and-effect between the vorticity and the velocity in this way is not consistent with the physics.[122][123][124] The velocity perturbations in the flow around a wing are in fact produced by the pressure field.[125]

Manifestations of lift in the farfield

[edit]Integrated force/momentum balance in lifting flows

[edit]

The flow around a lifting airfoil must satisfy Newton's second law regarding conservation of momentum, both locally at every point in the flow field, and in an integrated sense over any extended region of the flow. For an extended region, Newton's second law takes the form of the momentum theorem for a control volume, where a control volume can be any region of the flow chosen for analysis. The momentum theorem states that the integrated force exerted at the boundaries of the control volume (a surface integral), is equal to the integrated time rate of change (material derivative) of the momentum of fluid parcels passing through the interior of the control volume. For a steady flow, this can be expressed in the form of the net surface integral of the flux of momentum through the boundary.[126]

The lifting flow around a 2D airfoil is usually analyzed in a control volume that completely surrounds the airfoil, so that the inner boundary of the control volume is the airfoil surface, where the downward force per unit span is exerted on the fluid by the airfoil. The outer boundary is usually either a large circle or a large rectangle. At this outer boundary distant from the airfoil, the velocity and pressure are well represented by the velocity and pressure associated with a uniform flow plus a vortex, and viscous stress is negligible, so that the only force that must be integrated over the outer boundary is the pressure.[127][128][129] The free-stream velocity is usually assumed to be horizontal, with lift vertically upward, so that the vertical momentum is the component of interest.

For the free-air case (no ground plane), the force exerted by the airfoil on the fluid is manifested partly as momentum fluxes and partly as pressure differences at the outer boundary, in proportions that depend on the shape of the outer boundary, as shown in the diagram at right. For a flat horizontal rectangle that is much longer than it is tall, the fluxes of vertical momentum through the front and back are negligible, and the lift is accounted for entirely by the integrated pressure differences on the top and bottom.[127] For a square or circle, the momentum fluxes and pressure differences account for half the lift each.[127][128][129] For a vertical rectangle that is much taller than it is wide, the unbalanced pressure forces on the top and bottom are negligible, and lift is accounted for entirely by momentum fluxes, with a flux of upward momentum that enters the control volume through the front accounting for half the lift, and a flux of downward momentum that exits the control volume through the back accounting for the other half.[127]

The results of all of the control-volume analyses described above are consistent with the Kutta–Joukowski theorem described above. Both the tall rectangle and circle control volumes have been used in derivations of the theorem.[128][129]

Lift reacted by overpressure on the ground under an airplane

[edit]

An airfoil produces a pressure field in the surrounding air, as explained under "The wider flow around the airfoil" above. The pressure differences associated with this field die off gradually, becoming very small at large distances, but never disappearing altogether. Below the airplane, the pressure field persists as a positive pressure disturbance that reaches the ground, forming a pattern of slightly-higher-than-ambient pressure on the ground, as shown on the right.[130] Although the pressure differences are very small far below the airplane, they are spread over a wide area and add up to a substantial force. For steady, level flight, the integrated force due to the pressure differences is equal to the total aerodynamic lift of the airplane and to the airplane's weight. According to Newton's third law, this pressure force exerted on the ground by the air is matched by an equal-and-opposite upward force exerted on the air by the ground, which offsets all of the downward force exerted on the air by the airplane. The net force due to the lift, acting on the atmosphere as a whole, is therefore zero, and thus there is no integrated accumulation of vertical momentum in the atmosphere, as was noted by Lanchester early in the development of modern aerodynamics.[131]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b "What is Lift?". Glenn Research Center | NASA. NASA Glenn Research Center. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ Kulfan (2010)

- ^ Clancy, L. J., Aerodynamics, Section 14.6

- ^ a b c d e f g Doug McLean Aerodynamic Lift, Part 2: A comprehensive Physical Explanation The Physics teacher, November, 2018

- ^ Doug McLean Aerodynamic Lift, Part 1: The Science The Physics teacher, November, 2018

- ^ a b "There are many theories of how lift is generated. Unfortunately, many of the theories found in encyclopedias, on web sites, and even in some textbooks are incorrect, causing unnecessary confusion for students." NASA "Incorrect lift theory #1". August 16, 2000. Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ "Most of the texts present the Bernoulli formula without derivation, but also with very little explanation. When applied to the lift of an airfoil, the explanation and diagrams are almost always wrong. At least for an introductory course, lift on an airfoil should be explained simply in terms of Newton's Third Law, with the thrust up being equal to the time rate of change of momentum of the air downwards." Cliff Swartz et al. Quibbles, Misunderstandings, and Egregious Mistakes – Survey of High-School Physics Texts The Physics Teacher Vol. 37, May 1999 p. 300 [1] Archived August 25, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Arvel Gentry Proceedings of the Third AIAA Symposium on the Aero/Hydronautics of Sailing 1971. "The Aerodynamics of Sail Interaction" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 7, 2011. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

One explanation of how a wing . . gives lift is that as a result of the shape of the airfoil, the air flows faster over the top than it does over the bottom because it has farther to travel. Of course, with our thin-airfoil sails, the distance along the top is the same as along the bottom so this explanation of lift fails.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "An explanation frequently given is that the path along the upper side of the aerofoil is longer and the air thus has to be faster. This explanation is wrong." A comparison of explanations of the aerodynamic lifting force Klaus Weltner, Am. J. Phys. Vol.55 January 1, 1987

- ^ "The lift on the body is simple...it's the reaction of the solid body to the turning of a moving fluid...Now why does the fluid turn the way that it does? That's where the complexity enters in because we are dealing with a fluid. ...The cause for the flow turning is the simultaneous conservation of mass, momentum (both linear and angular), and energy by the fluid. And it's confusing for a fluid because the mass can move and redistribute itself (unlike a solid), but can only do so in ways that conserve momentum (mass times velocity) and energy (mass times velocity squared)... A change in velocity in one direction can cause a change in velocity in a perpendicular direction in a fluid, which doesn't occur in solid mechanics... So exactly describing how the flow turns is a complex problem; too complex for most people to visualize. So we make up simplified "models". And when we simplify, we leave something out. So the model is flawed. Most of the arguments about lift generation come down to people finding the flaws in the various models, and so the arguments are usually very legitimate." Tom Benson of NASA's Glenn Research Center in an interview with AlphaTrainer.Com "Archived copy – Tom Benson Interview". Archived from the original on April 27, 2012. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ^ Clancy, L. J., Aerodynamics, Section 5.2

- ^ McLean, Doug (2012). Understanding Aerodynamics: Arguing from the Real Physics. John Wiley & Sons. p. 281. ISBN 978-1119967514.

Another argument that is often made, as in several successive versions of the Wikipedia article "Aerodynamic Lift," is that lift can always be explained either in terms of pressure or in terms of momentum and that the two explanations are somehow "equivalent." This "either/or" approach also misses the mark.

- ^ "Both approaches are equally valid and equally correct, a concept that is central to the conclusion of this article." Charles N. Eastlake An Aerodynamicist's View of Lift, Bernoulli, and Newton The Physics Teacher Vol. 40, March 2002 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 11, 2009. Retrieved September 10, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Ison, David, "Bernoulli Or Newton: Who's Right About Lift?", Plane & Pilot, archived from the original on September 24, 2015, retrieved January 14, 2011

- ^ "...the effect of the wing is to give the air stream a downward velocity component. The reaction force of the deflected air mass must then act on the wing to give it an equal and opposite upward component." In: Halliday, David; Resnick, Robert, Fundamentals of Physics 3rd Ed., John Wiley & Sons, p. 378

- ^ Anderson and Eberhardt (2001)

- ^ a b Langewiesche (1944)

- ^ "When air flows over and under an airfoil inclined at a small angle to its direction, the air is turned from its course. Now, when a body is moving in a uniform speed in a straight line, it requires force to alter either its direction or speed. Therefore, the sails exert a force on the wind and, since action and reaction are equal and opposite, the wind exerts a force on the sails." In: Morwood, John, Sailing Aerodynamics, Adlard Coles Limited, p. 17

- ^ a. "Lift from Flow Turning". NASA Glenn Research Center. May 27, 2000. Archived from the original on July 5, 2011. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

Lift is a force generated by turning a moving fluid... If the body is shaped, moved, or inclined in such a way as to produce a net deflection or turning of the flow, the local velocity is changed in magnitude, direction, or both. Changing the velocity creates a net force on the body.

b. Vassilis Spathopoulos. "Flight Physics for Beginners: Simple Examples of Applying Newton's Laws The Physics Teacher Vol. 49, September 2011 p. 373". Archived from the original on June 18, 2013. Retrieved June 29, 2021.Essentially, due to the presence of the wing (its shape and inclination to the incoming flow, the so-called angle of attack), the flow is given a downward deflection. It is Newton's third law at work here, with the flow then exerting a reaction force on the wing in an upward direction, thus generating lift.

c. Langewiesche. Stick and Rudder, p. 6.The main fact of all heavier-than-air flight is this: the wing keeps the airplane up by pushing the air down.

- ^

a. Chris Waltham. "Flight without Bernoulli" (PDF). The Physics Teacher Vol. 36 Nov. 1998. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved August 4, 2011.

Birds and aircraft fly because they are constantly pushing air downwards: L = Δp/Δt where L= lift force, and Δp/Δt is the rate at which downward momentum is imparted to the airflow.

b. Clancy, L. J. Aerodynamics. Pitman 1975, p. 76.This lift force has its reaction in the downward momentum which is imparted to the air as it flows over the wing. Thus the lift of the wing is equal to the rate of transport of downward momentum of this air.

c. Smith, Norman F. (1972). "Bernoulli and Newton in Fluid Mechanics". The Physics Teacher. 10 (8): 451. Bibcode:1972PhTea..10..451S. doi:10.1119/1.2352317....if the air is to produce an upward force on the wing, the wing must produce a downward force on the air. Because under these circumstances air cannot sustain a force, it is deflected, or accelerated, downward. Newton's second law gives us the means for quantifying the lift force: Flift = m∆v/∆t = ∆(mv)/∆t. The lift force is equal to the time rate of change of momentum of the air.

- ^ "...when one considers the downwash produced by a lifting airfoil, the upper surface contributes more flow turning than the lower surface." Incorrect Theory #2 Glenn Research Center NASA https://www1.grc.nasa.gov/beginners-guide-to-aeronautics/foilw2/ Archived February 9, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ " This happens to some extent on both the upper and lower surface of the airfoil, but it is much more pronounced on the forward portion of the upper surface, so the upper surface gets the credit for being the primary lift producer. " Charles N. Eastlake An Aerodynamicist's View of Lift, Bernoulli, and Newton The Physics Teacher Vol. 40, March 2002 PDF Archived April 11, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The pressure reaches its minimum value around 5 to 15% chord after the leading edge. As a result, about half of the lift is generated in the first 1/4 chord region of the airfoil. Looking at all three angles of attack, we observe a similar pressure change after the leading edge. Additionally, in all three cases, the upper surface contributes more lift than the lower surface. As a result, it is critical to maintain a clean and rigid surface on the top of the wing. This is why most airplanes are cleared of any objects on the top of the wing." Airfoil Behavior: Pressure Distribution over a Clark Y-14 Wing David Guo, College of Engineering, Technology, and Aeronautics (CETA), Southern New Hampshire University https://www.jove.com/v/10453/airfoil-behavior-pressure-distribution-over-a-clark-y-14-wing Archived August 5, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "There's always a tremendous amount of focus on the upper portion of the wing, but the lower surface also contributes to lift." Bernoulli Or Newton: Who's Right About Lift? David Ison Plane & Pilot Feb 2016

- ^ Auerbach, David (2000), "Why Aircraft Fly", Eur. J. Phys., 21 (4): 289, Bibcode:2000EJPh...21..289A, doi:10.1088/0143-0807/21/4/302, S2CID 250821727

- ^ Denker, JS, Fallacious Model of Lift Production, archived from the original on March 2, 2009, retrieved August 18, 2008

- ^ Wille, R.; Fernholz, H. (1965), "Report on the first European Mechanics Colloquium, on the Coanda effect", J. Fluid Mech., 23 (4): 801, Bibcode:1965JFM....23..801W, doi:10.1017/S0022112065001702, S2CID 121981660

- ^ Anderson, David; Eberhart, Scott (1999), How Airplanes Fly: A Physical Description of Lift, archived from the original on January 26, 2016, retrieved June 4, 2008

- ^ Raskin, Jef (1994), Coanda Effect: Understanding Why Wings Work, archived from the original on September 28, 2007

- ^ Auerbach (2000)

- ^ Denker (1996)

- ^ Wille and Fernholz(1965)

- ^ White, Frank M. (2002), Fluid Mechanics (5th ed.), McGraw Hill

- ^ McLean, D. (2012), Section 7.3.2

- ^ McLean, D. (2012), Section 7.3.1.7

- ^ Burge, Cyril Gordon (1936). Encyclopædia of aviation. London: Pitman. p. 441. "… the fact that the air passing over the hump on the top of the wing has to speed up more than that flowing beneath the wing, in order to arrive at the trailing edge in the same time."

- ^ Illman, Paul (2000). The Pilot's Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 15–16. ISBN 0071345191. When air flows along the upper wing surface, it travels a greater distance in the same period of time as the airflow along the lower wing surface."

- ^ Dingle, Lloyd; Tooley, Michael H. (2005). Aircraft engineering principles. Boston: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 548. ISBN 0-7506-5015-X. The air travelling over the cambered top surface of the aerofoil shown in Figure 7.6, which is split as it passes around the aerofoil, will speed up, because it must reach the trailing edge of the aerofoil at the same time as the air that flows underneath the section."

- ^ "The airfoil of the airplane wing, according to the textbook explanation that is more or less standard in the United States, has a special shape with more curvature on top than on the bottom; consequently, the air must travel farther over the top surface than over the bottom surface. Because the air must make the trip over the top and bottom surfaces in the same elapsed time ..., the velocity over the top surface will be greater than over the bottom. According to Bernoulli's theorem, this velocity difference produces a pressure difference which is lift." Bernoulli and Newton in Fluid Mechanics Norman F. Smith The Physics Teacher November 1972 Volume 10, Issue 8, p. 451 [2] [permanent dead link]

- ^ Craig G.M. (1997), Stop Abusing Bernoulli

- ^ "Unfortunately, this explanation [fails] on three counts. First, an airfoil need not have more curvature on its top than on its bottom. Airplanes can and do fly with perfectly symmetrical airfoils; that is with airfoils that have the same curvature top and bottom. Second, even if a humped-up (cambered) shape is used, the claim that the air must traverse the curved top surface in the same time as it does the flat bottom surface...is fictional. We can quote no physical law that tells us this. Third—and this is the most serious—the common textbook explanation, and the diagrams that accompany it, describe a force on the wing with no net disturbance to the airstream. This constitutes a violation of Newton's third law." Bernoulli and Newton in Fluid Mechanics Norman F. Smith The Physics Teacher November 1972 Volume 10, Issue 8, p. 451 "Browse - the Physics Teacher". Archived from the original on March 17, 2012. Retrieved August 4, 2011.

- ^

Anderson, David (2001), Understanding Flight, New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 15, ISBN 978-0-07-136377-8,

The first thing that is wrong is that the principle of equal transit times is not true for a wing with lift.

- ^ Anderson, John (2005). Introduction to Flight. Boston: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. p. 355. ISBN 978-0072825695.

It is then assumed that these two elements must meet up at the trailing edge, and because the running distance over the top surface of the airfoil is longer than that over the bottom surface, the element over the top surface must move faster. This is simply not true

- ^ "Cambridge scientist debunks flying myth - Telegraph". Archived from the original on June 30, 2012. Retrieved June 10, 2012. Cambridge scientist debunks flying myth UK Telegraph 24 January 2012

- ^ Flow Visualization. National Committee for Fluid Mechanics Films/Educational Development Center. Archived from the original on October 21, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2009. A visualization of the typical retarded flow over the lower surface of the wing and the accelerated flow over the upper surface starts at 5:29 in the video.

- ^ "...do you remember hearing that troubling business about the particles moving over the curved top surface having to go faster than the particles that went underneath, because they have a longer path to travel but must still get there at the same time? This is simply not true. It does not happen." Charles N. Eastlake An Aerodynamicist's View of Lift, Bernoulli, and Newton The Physics Teacher Vol. 40, March 2002 PDF Archived April 11, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The actual velocity over the top of an airfoil is much faster than that predicted by the "Longer Path" theory and particles moving over the top arrive at the trailing edge before particles moving under the airfoil." Glenn Research Center (August 16, 2000). "Incorrect Lift Theory #1". NASA. Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ "As stream tube A flows toward the airfoil, it senses the upper portion of the airfoil as an obstruction, and stream tube A must move out of the way of this obstruction. In so doing, stream tube A is squashed to a smaller cross-sectional area as it flows over the nose of the airfoil. In turn, because of mass continuity (ρ AV = constant), the velocity of the flow in the stream tube must increase in the region where the stream tube is being squashed." J. D. Anderson (2008), Introduction to Flight (6th edition), section 5.19

- ^ "The theory is based on the idea that the airfoil upper surface is shaped to act as a nozzle which accelerates the flow. Such a nozzle configuration is called a Venturi nozzle and it can be analyzed classically. Considering the conservation of mass, the mass flowing past any point in the nozzle is a constant; the mass flow rate of a Venturi nozzle is a constant... For a constant density, decreasing the area increases the velocity." Incorrect Theory #3 Glenn Research Center NASA https://www1.grc.nasa.gov/beginners-guide-to-aeronautics/venturi-theory/ Archived February 9, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The problem with the 'Venturi' theory is that it attempts to provide us with the velocity based on an incorrect assumption (the constriction of the flow produces the velocity field). We can calculate a velocity based on this assumption, and use Bernoulli's equation to compute the pressure, and perform the pressure-area calculation and the answer we get does not agree with the lift that we measure for a given airfoil." NASA Glenn Research Center "Incorrect lift theory #3". August 16, 2000. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ "A concept...uses a symmetrical convergent-divergent channel, like a longitudinal section of a Venturi tube, as the starting point . . when such a device is put in a flow, the static pressure in the tube decreases. When the upper half of the tube is removed, a geometry resembling the airfoil is left, and suction is still maintained on top of it. Of course, this explanation is flawed too, because the geometry change affects the whole flowfield and there is no physics involved in the description." Jaakko Hoffren Quest for an Improved Explanation of Lift Section 4.3 American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics 2001 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 7, 2013. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "This answers the apparent mystery of how a symmetric airfoil can produce lift. ... This is also true of a flat plate at non-zero angle of attack." Charles N. Eastlake An Aerodynamicist's View of Lift, Bernoulli, and Newton "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 11, 2009. Retrieved September 10, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "This classic explanation is based on the difference of streaming velocities caused by the airfoil. There remains, however, a question: How does the airfoil cause the difference in streaming velocities? Some books don't give any answer, while others just stress the picture of the streamlines, saying the airfoil reduces the separations of the streamlines at the upper side. They do not say how the airfoil manages to do this. Thus this is not a sufficient answer." Klaus Weltner Bernoulli's Law and Aerodynamic Lifting Force The Physics Teacher February 1990 p. 84. [3] [permanent dead link]

- ^ Doug McLean Understanding Aerodynamics, section 7.3.1.5, Wiley, 2012

- ^ "There is nothing wrong with the Bernoulli principle, or with the statement that the air goes faster over the top of the wing. But, as the above discussion suggests, our understanding is not complete with this explanation. The problem is that we are missing a vital piece when we apply Bernoulli's principle. We can calculate the pressures around the wing if we know the speed of the air over and under the wing, but how do we determine the speed?" How Airplanes Fly: A Physical Description of Lift David Anderson and Scott Eberhardt "How Airplanes Fly". Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ A uniform pressure surrounding a body does not create a net force. (See buoyancy). Therefore pressure differences are needed to exert a force on a body immersed in a fluid. For example, see: Batchelor, G.K. (1967), An Introduction to Fluid Dynamics, Cambridge University Press, pp. 14–15, ISBN 978-0-521-66396-0

- ^ "...if a streamline is curved, there must be a pressure gradient across the streamline..." Babinsky, Holger (November 2003), "How do wings work?", Physics Education, 38 (6): 497, Bibcode:2003PhyEd..38..497B, doi:10.1088/0031-9120/38/6/001, S2CID 1657792

- ^ Thus a distribution of the pressure is created which is given in Euler's equation. The physical reason is the aerofoil which forces the streamline to follow its curved surface. The low pressure at the upper side of the aerofoil is a consequence of the curved surface." A comparison of explanations of the aerodynamic lifting force Klaus Weltner Am. J. Phys. Vol.55 No.January 1, 1987, p. 53 [4] Archived April 28, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "You can argue that the main lift comes from the fact that the wing is angled slightly upward so that air striking the underside of the wing is forced downward. The Newton's 3rd law reaction force upward on the wing provides the lift. Increasing the angle of attack can increase the lift, but it also increases drag so that you have to provide more thrust with the aircraft engines" Hyperphysics Georgia State University Dept. of Physics and Astronomy "Angle of Attack for Airfoil". Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ^ "If we enlarge the angle of attack we enlarge the deflection of the airstream by the airfoil. This results in the enlargement of the vertical component of the velocity of the airstream... we may expect that the lifting force depends linearly on the angle of attack. This dependency is in complete agreement with the results of experiments..." Klaus Weltner A comparison of explanations of the aerodynamic lifting force Am. J. Phys. 55(1), January 1987 p. 52

- ^ "The decrease[d lift] of angles exceeding 25° is plausible. For large angles of attack we get turbulence and thus less deflection downward." Klaus Weltner A comparison of explanations of the aerodynamic lifting force Am. J. Phys. 55(1), January 1987 p. 52

- ^ Clancy (1975), Section 5.2

- ^ Abbott, and von Doenhoff (1958), Section 4.2

- ^ "With an angle of attack of 0°, we can explain why we already have a lifting force. The air stream behind the aerofoil follows the trailing edge. The trailing edge already has a downward direction, if the chord to the middle line of the profile is horizontal." Klaus Weltner A comparison of explanations of the aerodynamic lifting force Am. J. Phys. 55(1), January 1987 p. 52

- ^ "...the important thing about an aerofoil . . is not so much that its upper surface is humped and its lower surface is nearly flat, but simply that it moves through the air at an angle. This also avoids the otherwise difficult paradox that an aircraft can fly upside down!" N. H. Fletcher Mechanics of Flight Physics Education July 1975 [5]

- ^ "It requires adjustment of the angle of attack, but as clearly demonstrated in almost every air show, it can be done." Hyperphysics GSU Dept. of Physics and Astronomy [6] Archived July 8, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ White (1991), Section 1-4

- ^ White (1991), Section 1-2

- ^ a b Anderson (1991), Chapter 17

- ^ a b Abbott and von Doenhoff (1958), Chapter 5

- ^ Schlichting (1979), Chapter XXIV

- ^ Abbott and Doenhoff (1958), Chapter 8

- ^ a b Williamson, C. H. K.; Govardhan, R. (2004), "Vortex-induced vibrations", Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics, 36: 413–455, Bibcode:2004AnRFM..36..413W, doi:10.1146/annurev.fluid.36.050802.122128, S2CID 58937745

- ^ Sumer, B. Mutlu; Fredsøe, Jørgen (2006), Hydrodynamics around cylindrical structures (revised ed.), World Scientific, pp. 6–13, 42–45 & 50–52, ISBN 978-981-270-039-1

- ^ Zdravkovich, M.M. (2003), Flow around circular cylinders, vol. 2, Oxford University Press, pp. 850–855, ISBN 978-0-19-856561-1

- ^ Clancy, L. J., Aerodynamics, Sections 4.5, 4.6

- ^ McLean (2012), Section 7.3.3

- ^ a b Milne-Thomson (1966), Section 1.41

- ^ Jeans (1967), Section 33.

- ^ a b Clancy (1975), Section 4.5

- ^ Milne-Thomson (1966.), Section 5.31

- ^ McLean 2012, Section 7.3.3.7

- ^ McLean (2012), Section 3.5

- ^ McLean 2012, Section 7.3.3.9"

- ^ McLean 2012, Section 7.3.3.9

- ^ McLean, Doug (2012). "7.3.3.12". Understanding Aerodynamics: Arguing from the Real Physics. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1119967514. Doug McLean, Common Misconceptions in Aerodynamics on YouTube

- ^ Anderson (2008), Section 5.7

- ^ Anderson, John D. (2004), Introduction to Flight (5th ed.), McGraw-Hill, p. 257, ISBN 978-0-07-282569-5

- ^ Yoon, Joe (December 28, 2003), Mach Number & Similarity Parameters, Aerospaceweb.org, archived from the original on February 24, 2021, retrieved February 11, 2009

- ^ Batchelor (1967), Section 1.2

- ^ Thwaites (1958), Section I.2

- ^ von Mises (1959), Section I.1

- ^ "Analysis of fluid flow is typically presented to engineering students in terms of three fundamental principles: conservation of mass, conservation of momentum, and conservation of energy." Charles N. Eastlake An Aerodynamicist's View of Lift, Bernoulli, and Newton The Physics Teacher Vol. 40, March 2002 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 11, 2009. Retrieved September 10, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ White (1991), Chapter 1

- ^ Batchelor (1967), Chapter 3

- ^ Aris (1989)

- ^ a b Spalart, Philippe R. (2000) Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Elsevier Science Publishers.

- ^ White (1991), Section 6-2

- ^ Schlichting(1979), Chapter XVIII

- ^ Anderson (1995)

- ^ "...whenever the velocity field is irrotational, it can be expressed as the gradient of a scalar function we call a velocity potential φ: V = ∇φ. The existence of a velocity potential can greatly simplify the analysis of inviscid flows by way of potential-flow theory..." Doug McLean Understanding Aerodynamics: Arguing from the Real Physics p. 26 Wiley "Continuum Fluid Mechanics and the Navier–Stokes Equations". Understanding Aerodynamics. 2012. p. 13. doi:10.1002/9781118454190.ch3. ISBN 9781118454190.

- ^ Elements of Potential Flow California State University Los Angeles "Faculty Web Directory". Archived from the original on November 11, 2012. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ^ Batchelor(1967), Section 2.7

- ^ Milne-Thomson(1966), Section 3.31

- ^ Clancy (1975), Section 4.8

- ^ Anderson(1991), Section 4.5

- ^ Clancy(1975), Sections 8.1–8

- ^ von Mises (1959), Section VIII.2

- ^ Anderson(1991), Section 3.15

- ^ Prandtl and Tietjens (1934)

- ^ Batchelor (1967), Section 6.7

- ^ Gentry (2006)

- ^ McLean (2012), Section 7.2.1

- ^ Milne-Thomson (1966), Section 12.3

- ^ McLean (2012), Section 8.1.3

- ^ McLean (2012), Section 8.1.1

- ^ Hurt, H. H. (1965) Aerodynamics for Naval Aviators, Figure 1.30, NAVWEPS 00-80T-80

- ^ Lanchester (1907)

- ^ Milne-Thomson (1966), Section 10.1

- ^ Clancy (1975), Section 8.9

- ^ Anderson (1991), Section 5.2

- ^ Batchelor (1967), Section 2.4

- ^ Milne-Thomson (1966), Section 9.3

- ^ Durand (1932), Section III.2

- ^ McLean (2012), Section 8.1

- ^ Shapiro (1953), Section 1.5, equation 1.15

- ^ a b c d Lissaman (1996), "Lift in thin slices: the two dimensional case"

- ^ a b c Durand (1932), Sections B.V.6, B.V.7

- ^ a b c Batchelor (1967), Section 6.4, p. 407

- ^ Prandtl and Tietjens (1934), Figure 150

- ^ Lanchester (1907), Sections 5 and 112

References

[edit]- Abbott, I. H.; von Doenhoff, A. E. (1958), Theory of Wing Sections, Dover Publications

- Anderson, D. F.; Eberhardt, S. (2001), Understanding Flight, McGraw-Hill

- Anderson, J. D. (1991), Fundamentals of Aerodynamics, 2nd ed., McGraw-Hill

- Anderson, J. D. (1995), Computational Fluid Dynamics, The Basics With Applications, McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-113210-7

- Anderson, J. D. (1997), A History of Aerodynamics, Cambridge University Press

- Anderson, J. D. (2004), Introduction to Flight (5th ed.), McGraw-Hill, pp. 352–361, §5.19, ISBN 978-0-07-282569-5

- Anderson, J. D. (2008), Introduction to Flight, 6th edition, McGraw Hill

- Aris, R. (1989), Vectors, Tensors, and the basic Equations of Fluid Mechanics, Dover Publications

- Auerbach, D. (2000), "Why Aircraft Fly", Eur. J. Phys., 21 (4): 289–296, Bibcode:2000EJPh...21..289A, doi:10.1088/0143-0807/21/4/302, S2CID 250821727

- Babinsky, H. (2003), "How do wings work?", Phys. Educ., 38 (6): 497, Bibcode:2003PhyEd..38..497B, doi:10.1088/0031-9120/38/6/001, S2CID 1657792

- Batchelor, G. K. (1967), An Introduction to Fluid Dynamics, Cambridge University Press

- Clancy, L. J. (1975), Aerodynamics, Longman Scientific and Technical

- Craig, G. M. (1997), Stop Abusing Bernoulli, Anderson, Indiana: Regenerative Press

- Durand, W. F., ed. (1932), Aerodynamic Theory, vol. 1, Dover Publications

- Eastlake, C. N. (2002), "An Aerodynamicist's View of Lift, Bernoulli, and Newton", The Physics Teacher, 40 (3): 166–173, Bibcode:2002PhTea..40..166E, doi:10.1119/1.1466553, S2CID 121425815

- Jeans, J. (1967), An Introduction to the Kinetic theory of Gasses, Cambridge University Press

- Kulfan, B. M. (2010), Paleoaerodynamic Explorations Part I: Evolution of Biological and Technical Flight, AIAA 2010-154

- Lanchester, F. W. (1907), Aerodynamics, A. Constable and Co.

- Langewiesche, W. (1944), Stick and Rudder – An Explanation of the Art of Flying, McGraw-Hill

- Lissaman, P. B. S. (1996), The facts of lift, AIAA 1996-161

- Marchai, C. A. (1985), Sailing Theory and Practice, Putnam

- McBeath, S. (2006), Competition Car Aerodynamics, Sparkford, Haynes

- McLean, D. (2012), Understanding Aerodynamics – Arguing from the Real Physics, Wiley

- Milne-Thomson, L. M. (1966), Theoretical Aerodynamics, 4th ed., Dover Publications

- Prandtl, L.; Tietjens, O. G. (1934), Applied Hydro- and Aeromechanics, Dover Publications

- Raskin, J. (1994), Coanda Effect: Understanding Why Wings Work, archived from the original on September 28, 2007

- Schlichting, H. (1979), Boundary-Layer Theory, Seventh Ed., McGraw-Hill

- Shapiro, A. H. (1953), The Dynamics and Thermodynamics of Compressible Fluid Flow, Ronald Press Co., Bibcode:1953dtcf.book.....S

- Smith, N. F. (1972), "Bernoulli and Newton in Fluid Mechanics", The Physics Teacher, 10 (8): 451, Bibcode:1972PhTea..10..451S, doi:10.1119/1.2352317

- Spalart, Philippe R. (2000), "Strategies for turbulence modeling and simulations", International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow, 21 (3): 252, Bibcode:2000IJHFF..21..252S, doi:10.1016/S0142-727X(00)00007-2

- Sumer, B.; Mutlu; Fredsøe, Jørgen (2006), Hydrodynamics around cylindrical structures (revised ed.)

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Thwaites, B., ed. (1958), Incompressible Aerodynamics, Dover Publications

- Tritton, D. J. (1980), Physical Fluid Dynamics, Van Nostrand Reinhold

- Van Dyke, M. (1969), "Higher-Order Boundary-Layer Theory", Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics, 1 (1): 265–292, Bibcode:1969AnRFM...1..265D, doi:10.1146/annurev.fl.01.010169.001405

- von Mises, R. (1959), Theory of Flight, Dover Publications

- Waltham, C. (1998), "Flight without Bernoulli", The Physics Teacher, 36 (8): 457–462, Bibcode:1998PhTea..36..457W, doi:10.1119/1.879927