Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Epigraphy

View on Wikipedia

Epigraphy (from Ancient Greek ἐπιγραφή (epigraphḗ) 'inscription') is the study of inscriptions, or epigraphs, as writing; it is the science of identifying graphemes, clarifying their meanings, classifying their uses according to dates and cultural contexts, and drawing conclusions about the writing and the writers. Specifically excluded from epigraphy are the historical significance of an epigraph as a document and the artistic value of a literary composition. A person using the methods of epigraphy is called an epigrapher or epigraphist. For example, the Behistun inscription is an official document of the Achaemenid Empire engraved on native rock at a location in Iran. Epigraphists are responsible for reconstructing, translating, and dating the trilingual inscription and finding any relevant circumstances. It is the work of historians, however, to determine and interpret the events recorded by the inscription as document. Often, epigraphy and history are competences practised by the same person. Epigraphy is a primary tool of archaeology when dealing with literate cultures.[1] The US Library of Congress classifies epigraphy as one of the auxiliary sciences of history.[2] Epigraphy also helps identify a forgery:[3] epigraphic evidence formed part of the discussion concerning the James Ossuary.[4][5]

An epigraph (not to be confused with epigram) is any sort of text, from a single grapheme (such as marks on a pot that abbreviate the name of the merchant who shipped commodities in the pot) to a lengthy document (such as a treatise, a work of literature, or a hagiographic inscription). Epigraphy overlaps other competences such as numismatics or palaeography. When compared to books, most inscriptions are short. The media and the forms of the graphemes are diverse: engravings in stone or metal, scratches on rock, impressions in wax, embossing on cast metal, cameo or intaglio on precious stones, painting on ceramic or in fresco. Typically the material is durable, but the durability might be an accident of circumstance, such as the baking of a clay tablet in a conflagration.

The character of the writing, the subject of epigraphy, is a matter quite separate from the nature of the text, which is studied in itself. Texts inscribed in stone are usually for public view and so they are essentially different from the written texts of each culture. Not all inscribed texts are public, however: in Mycenaean Greece the deciphered texts of "Linear B" were revealed to be largely used for economic and administrative record keeping. Informal inscribed texts are "graffiti" in its original sense.

The study of ideographic inscriptions, that is inscriptions representing an idea or concept, may also be called ideography. The German equivalent Sinnbildforschung was a scientific discipline in the Third Reich, but was later dismissed as being highly ideological.[6] Epigraphic research overlaps with the study of petroglyphs, which deals with specimens of pictographic, ideographic and logographic writing. The study of ancient handwriting, usually in ink, is a separate field, palaeography.[7] Epigraphy also differs from iconography, as it confines itself to meaningful symbols containing messages, rather than dealing with images.

History

[edit]

The science of epigraphy has been developing steadily since the 16th century. Principles of epigraphy vary culture by culture, and the infant science in Europe initially concentrated on Latin inscriptions. Individual contributions have been made by epigraphers such as Georg Fabricius (1516–1571); Stefano Antonio Morcelli (1737–1822); Luigi Gaetano Marini (1742–1815); August Wilhelm Zumpt (1815–1877); Theodor Mommsen (1817–1903); Emil Hübner (1834–1901); Franz Cumont (1868–1947); Louis Robert (1904–1985).

The Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum, begun by Mommsen and other scholars, has been published in Berlin since 1863, with wartime interruptions. It is the largest and most extensive collection of Latin inscriptions. New fascicles are still produced as the recovery of inscriptions continues. The Corpus is arranged geographically: all inscriptions from Rome are contained in volume 6. This volume has the greatest number of inscriptions; volume 6, part 8, fascicle 3 was just recently published (2000). Specialists depend on such on-going series of volumes in which newly discovered inscriptions are published, often in Latin, not unlike the biologists' Zoological Record – the raw material of history.

Greek epigraphy has unfolded in the hands of a different team, with different corpora. There are two. The first is Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum of which four volumes came out, again at Berlin, 1825–1877. This marked a first attempt at a comprehensive publication of Greek inscriptions copied from all over the Greek-speaking world. Only advanced students still consult it, for better editions of the texts have superseded it. The second, modern corpus is Inscriptiones Graecae arranged geographically under categories: decrees, catalogues, honorary titles, funeral inscriptions, various, all presented in Latin, to preserve the international neutrality of the field of classics.

Other such series include the Corpus Inscriptionum Etruscarum (Etruscan inscriptions), Corpus Inscriptionum Crucesignatorum Terrae Sanctae (Crusaders' inscriptions), Corpus Inscriptionum Insularum Celticarum (Celtic inscriptions), Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum (Iranian inscriptions), "Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia" and "Royal Inscriptions of the Neo-Assyrian Period" (Sumerian and Akkadian inscriptions) and so forth.

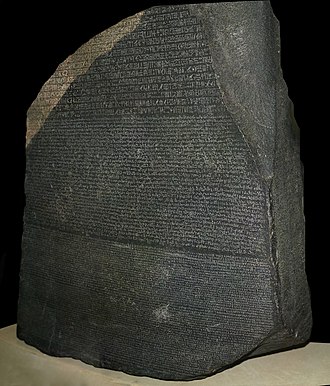

Egyptian hieroglyphs were solved using the Rosetta Stone, which was a multilingual stele in Classical Greek, Demotic Egyptian and Classical Egyptian hieroglyphs. The work was done by the French scholar, Jean-François Champollion, and the British scientist Thomas Young.

The interpretation of Maya hieroglyphs was lost as a result of the Spanish Conquest of Central America. However, recent work by Maya epigraphers and linguists has yielded a considerable amount of information on this complex writing system.[8]

Form

[edit]Materials and technique

[edit]

Content

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2019) |

Greek inscriptions

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2019) |

Political and social

[edit]Codes of law and regulations

[edit]Ancient writers state that the earliest laws of Athens were inscribed upon tablets of wood, put together in a pyramidal shape. These, owing to their material, have perished; but we have some very early codes of law preserved on stone, notably at Gortyna in Crete. Here an inscription of great length is incised on the slabs of a theatre-shaped structure in 12 columns of 50 lines each; it is mainly concerned with the law of inheritance, adoption, etc. Doubtless similar inscriptions were set up in many places in Greece. An interesting series of inscriptions deals with the conditions under which colonists were sent out from various cities, and the measures that were taken to secure their rights as citizens. A bronze tablet records in some detail the arrangements of this sort made when Locrians established a colony in Naupactus; another inscription relates to the Athenian colonisation of Salamis, in the 6th century BC.

Decrees of people and rulers, later of kings and emperors

[edit]A very large number of inscriptions are in the form of decrees of various cities and peoples, even when their subject matter suggests that they should be classified under other headings. Almost all legislative and many administrative measures take this form; often a decree prescribes how and where the inscription should be set up. The formulae and preambles of such decrees vary considerably from place to place, and from period to period. Those of Athens are by far the most exactly known, owing to the immense number that have been discovered; and they are so strictly stereotyped that can be classified with the precision of algebraic formulae, and often dated to within a few years by this test alone. Very full lists for this purpose have been drawn up by epigraphist Wilhelm Larfeld, in his work on the subject.[9] It is usual to record the year (by the name of the eponymous archon), the day of the month and of the prytany (or presiding commission according to tribes), various secretaries, the presiding officials and the proposer of the decree. It is also stated whether the resolution is passed by the senate (Boule) or the assembly of the people (Ecclesia), or both. The circumstances or the reason of the resolution are then given, and finally the decision itself. Some other cities followed Athens in the form of their decrees, with such local variations as were required; others were more independent in their development, and different magistracies or forms of government had various results. In the Hellenistic Age, and later, the forms of independent government were, to a great extent, kept up, though little real power remained with the people. On the other hand, it is common thing to find letters from kings, and later from Roman emperors, inscribed and set up in public places.

Public accounts, treasure lists, building inscriptions

[edit]It was customary to inscribe on stone all records of the receipt, custody and expenditure of public money or treasure, so that citizens could verify for themselves the safety and due control of the State in all financial matters. As in the case of temple accounts, it was usual for each temporary board of officials to render to their successors an account of their stewardship, and of the resources and treasures which they handed over. In all cases of public works, the expenditure was ordered by the State, and detailed reports were drawn up and inscribed on stone at intervals while the work was being carried out. In many cases there is a detailed specification of building work which makes it possible, not only to realise all the technical details and processes employed, but also the whole plan and structure of a building. A notable instance is the arsenal of Philon at the Peiraeus which has been completely reconstructed on paper by architects from the building specification.[10] In the case of the Erechtheum, we have not only a detailed report on the unfinished state of the building in 409 BC, but also accounts of the expenditure and payments to the workmen employed in finishing it. Similar accounts have been preserved of the building of the Parthenon, spread over 15 years; in the case of both the Parthenon and the Erechtheum, there are included the payments made to those who made the sculptures.[11][12]

Naval and military expenditure is also fully accounted for; among other information there are records of the galley-slips at the different harbours of the Piraeus, and of the ships of the Athenian navy, with their names and condition. In short, there is no department of state economy and financial administration that is not abundantly illustrated by the record of inscriptions.[10] A set of records of high historical value are the "tribute lists", recording the quota paid to Athens by her subject allies during the 5th century BC. These throw much light on her relations with them at various periods.(Cf. Delian League).

Ephebic inscriptions

[edit]An institution as to which our knowledge is mainly derived from inscriptions is the ephebic system at Athens. There are not only records of lists of ephebi and of their guardians and instructors, but also decrees in honour of their services, especially in taking their due part in religious and other ceremonies, and resolutions of the ephebi themselves in honour of their officials. It is possible to trace in the inscriptions, which range over several centuries, how what was originally a system of physical and military training for Athenian youths from age of 18 to 20, with outpost and police duties, was gradually transformed. In later times there were added to the instructors in military exercises others who gave lectures on what we should now call arts and science subjects; so that in the Hellenistic and Roman times, when youths from all parts of the civilised world flocked to Athens as an intellectual centre, the ephebic system became a kind of cosmopolitan university.[13]

Treaties and political and commercial agreements; arbitration, etc.

[edit]In addition to inscriptions which are concerned with the internal affairs of various cities, there are many others recording treaties or other agreements of an international character between various cities and states. These were incised on bronze or stone, and set up in places of public resort in the cities concerned, or in common religious centres such as Olympia and Delphi. The simplest form of treaty is merely an alliance for a certain term of years, usually with some penalty for any breach of the conditions. Often an oath was prescribed, to be taken by representatives on each side; it was also not unusual to appeal to the god in whose temple the treaty was exhibited. In other cases a list of gods by whom the two parties must swear is prescribed. Commercial clauses were sometimes added to treaties of alliance, and commercial treaties are also found, agreeing as to the export and import of merchandise and other things. In later days, especially in the time of the Hellenistic kings, treaties tend to become more complicated and detailed in their provisions.[14]

Another series of records of great historical interest is concerned with arbitration between various states on various questions, mainly concerned with frontiers. In cases of dispute it was not uncommon for the two disputants to appoint a third party as arbitrator. Sometimes this third party was another State, sometimes a specified number of individuals. Thus, in a frontier dispute between Corinth and Epidaurus, 151 citizens of Megara were appointed by name to arbitrate, and when the decision was disputed, 31 from among them revised and confirmed it. In all such cases it was the custom for a full record to be preserved on stone and set up in the places concerned. In this case the initiative in referring the matter to arbitration came from the Achaean League.

Proxenia decrees

[edit]A very large class of inscriptions deals with the institution of proxenia. According to this a citizen of any State might be appointed proxenos of another State; his duties would then be to offer help and hospitality to any citizen of that other State who might be visiting his city, and to assist him in any dispute or in securing his legal rights. The office has been compared to the modern appointment of consuls, with the essential difference that the proxenos is always a citizen of the state in which he resides, not of that whose citizens and interests he assists. The decrees upon this matter frequently record the appointment of a proxenos, and the conferring on him of certain benefits and privileges in return for his services; they also contain resolutions of thanks from the city served by the proxenos, and record honours consequently conferred upon him.[15]

Honours and privileges given to individuals

[edit]This class of inscription is in form not unlike the last, except that honours recorded are given for all sorts of services, private and public, to the State and to individuals. A frequent addition is an invitation to dine in the Prytaneum at Athens. Some are inscribed on the bases of statues set up to the recipient. In early times these inscriptions are usually brief and simple. The bust of Pericles on the Acropolis held nothing but the names of Pericles himself and of the sculptor Kresilas. Later it became usual to give, in some detail, the reasons for the honours awarded; and in Hellenistic and Roman times, these became more and more detailed and fulsome in laudatory detail.

Signatures of artists

[edit]

These inscriptions are of special interest as throwing much light upon the history of art. The artist's name was usually, especially in earlier times, carved upon the base of the pedestal of a statue, and consequently was easily separated from it if the statue was carried off or destroyed. A case where both statue and pedestal are preserved is offered by the Victory, signed on its pedestal by Paeonius at Olympia. Occasionally, and more frequently in later times, the artist's signature was carved upon some portion of the statue itself. But in later copies of well-known works, it has to be considered whether the name is that of the original artist or of the copyist who reproduced his work. (see for example, the statue of Hercules/Heracles below)

A special class of artists' signatures is offered by the names signed by Attic and other vase painters upon their vases. These have been made the basis of a minute historical and stylistic study of the work of these painters, and unsigned vases also have been grouped with the signed ones, so as to make an exact and detailed record of this branch of Greek artistic production.[16]

Historical records

[edit]The great majority of these fall into one of the classes already referred to. But there are some instances in which an inscription is set up merely as a record. For instance, a victor in athletic or other contests may set up a list of his victories. The most famous historical record is the autobiographical account of the deeds and administration of Augustus, which was reproduced and set up in many places; it is generally known as the Monumentum Ancyranum, because the most complete copy of it was found at Ancyra. The Marmor Parium at Oxford, found in Paros, is a chronological record of Greek history, probably made for educational purposes, and valuable as giving the traditional dates of events from the earliest time down.[17]

Tombs and epitaphs

[edit]This is by far the most numerous class of inscriptions, both Greek and Latin. In early times there is often no record beyond the name of the deceased in Athens, often with the name of his father and his deme. Sometimes a word or two of conventional praise is added, such as "a good and wise man". Occasionally the circumstances of death are alluded to, especially if it took place in battle or at sea. Such epitaphs were frequently in metrical form, usually either hexameter or elegiacs. Many of them have been collected, and they form an interesting addition to the Greek anthology. In later times it becomes usual to give more elaborate praise of the deceased; but this is hardly ever so detailed and fulsome as on more modern tombstones. The age and other facts about the deceased are occasionally given, but not nearly so often as on Latin tombstones, which offer valuable statistical information in this respect.[18]

Boundary stones

[edit]In the Roman Near East, the Diocletian boundary stones stand out as rare inscriptions recording rural land surveys and village names.[19][20]

Latin inscriptions

[edit]

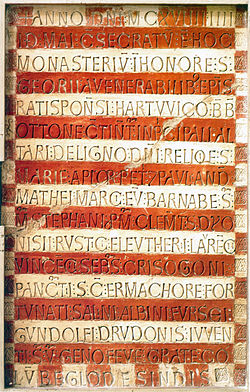

Latin inscriptions may be classified on much the same lines as Greek; but certain broad distinctions may be drawn at the outset. They are generally more standardised as to form and as to content, not only in Rome and Italy, but also throughout the provinces of the Roman Empire. One of the chief difficulties in deciphering Latin Inscriptions lies in the very extensive use of initials and abbreviations. These are of great number and variety, and while some of them can be easily interpreted as belonging to well-known formulae, others offer considerable difficulty, especially to the inexperienced student.[21] Often the same initial may have many different meanings according to the context. Some common formulae such as V.S.L.M. (votum solvit libens merito), or H.M.H.N.S. (hoc monumentum heredem non sequetur) offer little difficulty, but there are many which are not so obvious and leave room for conjecture. Often the only way to determine the meaning is to search through a list of initials, such as those given by modern Latin epigraphists, until a formula is found which fits the context.

Most of what has been said about Greek inscriptions applies to Roman also. The commonest materials in this case also are stone, marble and bronze; but a more extensive use is made of stamped bricks and tiles, which are often of historical value as identifying and dating a building or other construction. The same applies to leaden water pipes which frequently bear dates and names of officials. Terracotta lamps also frequently have their makers' names and other information stamped upon them. Arms, and especially shields, sometimes bear the name and corps of their owners. Leaden discs were also used to serve the same purpose as modern identification discs. Inscriptions are also found on sling bullets – Roman as well as Greek; there are also numerous classes of tesserae or tickets of admission to theatres or other shows.

As regards the contents of inscriptions, there must evidently be a considerable difference between records of a number of independent city states and an empire including almost all the civilised world; but municipalities maintained much of their independent traditions in Roman times, and consequently their inscriptions often follow the old formulas.

The classification of Roman inscriptions may, therefore, follow the same lines as the Greek, except that certain categories are absent, and that some others, not found in Greek, are of considerable importance.

Religious

[edit]Dedications and foundations of temples, etc.

[edit]

These are very numerous; and the custom of placing the name of the dedicator in a conspicuous place on the building was prevalent, especially in the case of dedications by emperors or officials, or by public bodies. Restoration or repair was often recorded in the same manner. In the case of small objects the dedication is usually simple in form; it usually contains the name of the god or other recipient and of the donor, and a common formula is D.D. (dedit, donavit) often with additions such as L.M. (libens merito). Such dedications are often the result of a vow, and V.S. (votum solvit) is therefore often added. Bequests made under the wills of rich citizens are frequently recorded by inscriptions; these might either be for religious or for social purposes.

Priests and officials

[edit]A priesthood was frequently a political office and consequently is mentioned along with political honours in the list of a man's distinctions. The priesthoods that a man had held are usually mentioned first in inscriptions before his civil offices and distinctions. Religious offices, as well as civil, were restricted to certain classes, the highest to those of senatorial rank, the next to those of equestrian status; many minor offices, both in Rome and in the provinces, are enumerated in their due order.

Regulations as to religion and cult

[edit]Among the most interesting of these is the ancient song and accompanying dance performed by the priests known as the Arval Brothers. This is, however, not in the form of a ritual prescription, but a detailed record of the due performance of the rite. An important class of documents is the series of calendars that have been found in Rome and in the various Italian towns. These give notice of religious festivals and anniversaries, and also of the days available for various purposes.

Colleges

[edit]The various colleges for religious purposes were very numerous. Many of them, both in Rome and Italy, and in provincial municipalities, were of the nature of priesthoods. Some were regarded as offices of high distinction and were open only to men of senatorial rank; among these were the Augurs, the Fetiales, the Salii; also the Sodales Divorum Augustorum in imperial times. The records of these colleges sometimes give no information beyond the names of members, but these are often of considerable interest. Haruspices and Luperci were of equestrian rank.

Political and social

[edit]Codes of law and regulations

[edit]Our information as to these is not mainly drawn from inscriptions and, therefore, they need not here be considered. On the other hand, the word lex (law) is usually applied to all decrees of the senate or other bodies, whether of legislative or of administrative character. It is therefore, best to consider all together under the heading of public decrees.

Laws and plebiscites, senatus consulta, decrees of magistrates or later of emperors

[edit]A certain number of these dating from republican times are of considerable interest. One of the earliest relates to the prohibition of bacchanalian orgies in Italy; it takes the form of a message from the magistrates, stating the authority on which they acted. Laws all follow a fixed formula, according to the body which has passed them. First there is a statement that the legislative body was consulted by the appropriate magistrate in due form; then follows the text of the law; and finally the sanction, the statement that the law was passed. In decrees of the senate the formula differs somewhat. They begin with a preamble giving the names of the consulting magistrates, the place and conditions of the meeting; then comes the subject submitted for decision, ending with the formula QDERFP (quid de ea re fieri placeret); then comes the decision of the senate, opening with DERIC (de ea re ita censuerunt). C. is added at the end, to indicate that the decree was passed. In imperial times, the emperor sometimes addressed a speech to the senate, advising them to pass certain resolutions, or else, especially in later times, gave orders or instructions directly, either on his own initiative or in response to questions or references. The number and variety of such orders is such that no classification of them can be given here. One of the most famous is the edict of Diocletian, fixing the prices of all commodities. Copies of this in Greek as well as in Latin have been found in various parts of the Roman Empire.[23]

Records of buildings, etc.

[edit]

A very large number of inscriptions record the construction or repair of public buildings by private individuals, by magistrates, Roman or provincial, and by emperors. In addition to the dedication of temples, we find inscriptions recording the construction of aqueducts, roads, especially on milestones, baths, basilicas, porticos and many other works of public utility. In inscriptions of early period often nothing is given but the name of the person who built or restored the edifice and a statement that he had done so. But later it was usual to give more detail as to the motive of the building, the name of the emperor or a magistrate giving the date, the authority for the building and the names and distinctions of the builders; then follows a description of the building, the source of the expenditure (e.g., S.P., sua pecunia) and finally the appropriate verb for the work done, whether building, restoring, enlarging or otherwise improving. Other details are sometimes added, such as the name of the man under whose direction the work was done.

Military documents

[edit]

These vary greatly in content, and are among the most important documents concerning the administration of the Roman Empire. "They are numerous and of all sorts – tombstones of every degree, lists of soldiers' burial clubs, certificates of discharge from service, schedules of time-expired men, dedications of altars, records of building or of engineering works accomplished. The facts directly commemorated are rarely important."[24] But when the information from hundreds of such inscriptions is collected together, "you can trace the whole policy of the Imperial Government in the matter of recruiting, to what extent and till what date legionaries were raised in Italy; what contingents for various branches of the service were drawn from the provinces, and which provinces provided most; how far provincials garrisoned their own countries, and which of them, like the British recruits, were sent as a measure of precaution to serve elsewhere; or, finally, at what epoch the empire grew weak enough to require the enlistment of barbarians from beyond its frontiers."[24]

Treaties and agreements

[edit]There were many treaties between Rome and other states in republican times; but we do not, as a rule, owe our knowledge of these to inscriptions, which are very rare in this earlier period. In imperial times, to which most Latin inscriptions belong, international relations were subject to the universal domination of Rome, and consequently the documents relating to them are concerned with reference to the central authority, and often take the form of orders from the emperor.

Proxeny

[edit]This custom belonged to Greece. What most nearly corresponded to it in Roman times was the adoption of some distinguished Roman as its patron, by a city or state. The relation was then recorded, usually on a bronze tablet placed in some conspicuous position in the town concerned. The patron probably also kept a copy in his house, or had a portable tablet which would ensure his recognition and reception.

Honorary

[edit]Honorary inscriptions are extremely common in all parts of the Roman world. Sometimes they are placed on the bases of statues, sometimes in documents set up to record some particular benefaction or the construction of some public work. The offices held by the person commemorated, and the distinctions conferred upon him are enumerated in a regularly established order (cursus honorum), either beginning with the lower and proceeding step by step to the higher, or in reverse order with the highest first. Religious and priestly offices are usually mentioned before civil and political ones. These might be exercised either in Rome itself, or in the various municipalities of the empire. There was also a distinction drawn between offices that might be held only by persons of senatorial rank, those that were assigned to persons of equestrian rank, and those of a less distinguished kind. It follows that when only a portion of an inscription has been found, it is often possible to restore the whole in accordance with the accepted order.

Signatures of artists

[edit]When these are attached to statues, it is sometimes doubtful whether the name is that of the man who actually made the statue, or of the master whose work it reproduces. Thus there are two well-known copies of a statue of Hercules by Lysippus, of which one is said to be the work of Lysippus, and the other states that it was made by Glycon (see images). Another kind of artist's or artificer's signature that is commoner in Roman times is to be found in the signatures of potters upon lamps and various kinds of vessels; they are usually impressed on the mould and stand out in relief on the terracotta or other material. These are of interest as giving much information as to the commercial spread of various kinds of handicrafts, and also as to the conditions under which they were manufactured.

Historical records

[edit]Many of these inscriptions might well be assigned to one of the categories already considered. But there are some which were expressly made to commemorate an important event, or to preserve a record. Among the most interesting is the inscription of the Columna Rostrata in Rome, which records the great naval victory of Gaius Duilius over the Carthaginians; this, however, is not the original, but a later and somewhat modified version. A document of high importance is a summary of the life and achievements of Augustus, already mentioned, and known as the Monumentum Ancyranum. The various sets of Fasti constituted a record of the names of consuls, and other magistrates or high officials, and also of the triumphs accorded to conquering generals.

Inscriptions on tombs

[edit]

These are probably the most numerous of all classes of inscriptions; and though many of them are of no great individual interest, they convey, when taken collectively, much valuable information as to the distribution and transference of population, as to trades and professions, as to health and longevity, and as to many other conditions of ancient life. The most interesting early series is that on the tombs of the Scipios at Rome, recording, mostly in Saturnian Metre, the exploits and distinctions of the various members of that family.[25]

About the end of the republic and the beginning of the empire, it became customary to head a tombstone with the letters D.M. or D.M.S. (Dis Manibus sacrum), thus consecrating the tomb to the deceased as having become members of the body of ghosts or spirits of the dead. These are followed by the name of the deceased, usually with his father's name and his tribe, by his honours and distinctions, sometimes by a record of his age. The inscription often concludes with H.I. (Hic iacet), or some similar formula, and also, frequently, with a statement of boundaries and a prohibition of violation or further use – for instance, H.M.H.N.S. (hoc monumentum heredem non sequetur, this monument is not to pass to the heir). The person who has erected the monument and his relation to the deceased are often stated; or if a man has prepared the tomb in his lifetime, this also may be stated, V.S.F. (vivus sibi fecit). But there is an immense variety in the information that either a man himself or his friend may wish to record.[25]

Milestones and boundaries

[edit]Milliarium (milestones) have already been referred to, and may be regarded as records of the building of roads. Boundary stones (termini) are frequently found, both of public and private property. A well-known instance is offered by those set up by the commissioners called III. viri A.I.A. (agris iudicandis adsignandis) in the time of the Gracchi.[26]

Sanskrit inscriptions

[edit]Sanskrit epigraphy, the study of ancient inscriptions in Sanskrit, offers insight into the linguistic, cultural, and historical evolution of South Asia and its neighbors. Early inscriptions, such as those from the 1st century BC in Ayodhya and Hathibada, are written in Brahmi script and reflect the transition to classical Sanskrit. The Mathura inscriptions from the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, including the Mora Well and Vasu Doorjamb inscriptions, represent significant contributions to the early use of Sanskrit, often linked to Hindu and Jaina traditions.[27][28]

The turning point in Sanskrit epigraphy came with the Rudradaman I inscription from the mid-2nd century CE, which established a poetic eulogy style later adopted during the Gupta Empire. This era saw Sanskrit become the predominant language for royal and religious records, documenting donations, public works, and the glorification of rulers. In South India, inscriptions such as those from Nagarjunakonda and Amaravati illustrate early use in Buddhist and Shaivite contexts, transitioning to exclusive Sanskrit use from the 4th century CE.[27]: 89, 91–94, 110–126

Sanskrit inscriptions extended beyond South Asia, influencing Southeast Asia from the 4th century CE onward. Indic scripts adapted for Sanskrit were found in regions like Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Cambodia, where they evolved into local scripts such as Khmer, Javanese, and Balinese. These inscriptions highlight the spread of Indian cultural and religious practices.[29][30]: 143–144 [27]: 92–93

See also

[edit]Related fields of study

[edit]

|

|

Types of inscription

[edit]Notable inscriptions

[edit]- Behistun Inscription

- Bitola inscription

- Bryggen inscriptions

- Decree of Themistocles

- Dipylon inscription

- Duenos Inscription

- Edicts of Ashoka

- Inscription of Abercius

- Kedukan Bukit

- Kuntillet Ajrud inscriptions

- Laguna Copperplate Inscription

- La Mojarra Stela 1

- Malia altar stone

- Phaistos Disc

- Res Gestae Divi Augusti

- Rosetta Stone

- Shugborough inscription

- Priene Inscription

- Punic-Libyan Inscription

- The Antikythera mechanism is notable for the novel techniques used in reading the inscriptions.

- Beccut cippus

References

[edit]- ^ Bozia, Eleni; Barmpoutis, Angelos; Wagman, Robert S. (2014). "OPEN-ACCESS EPIGRAPHY. Electronic Dissemination of 3D-digitized. Archaeological Material" (PDF). Hypotheses.org: 12. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ Drake, Miriam A. (2003). Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science. Dekker Encyclopedias Series. Vol. 3. CRC Press. ISBN 0-8247-2079-2.

- ^ Orlandi, Silvia; Caldelli, Maria Letizia; Gregori, Gian Luca (November 2014). Bruun, Christer; Edmondson, Jonathan (eds.). "Forgeries and Fakes". The Oxford Handbook of Roman Epigraphy. Oxford Handbooks. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195336467.013.003. ISBN 9780195336467.

- ^ Silberman, Neil Asher; Goren, Yuval (September–October 2003). "Faking Biblical History: How wishful thinking and technology fooled some scholars – and made fools out of others". Archaeology. Vol. 56, no. 5. Archaeological Institute of America. pp. 20–29. JSTOR 41658744. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ^ Shanks, Hershel. "Related Coverage on the James Ossuary and Forgery Trial". Biblical Archaeology Review. Archived from the original on 7 September 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- ^ Mees, Bernard Thomas, The Science of the Swastika, Budapest / New York 2008.

- ^ Brown, Julian. "What is Palaeography?" (PDF). UMassAmherst. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Michael D. Coe (1992). Breaking the Maya Code. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05061-9. OCLC 26605966.

- ^ Cf. his classic work (downloadable) Griechische Epigraphik (1914) at University of Toronto – Robarts Library, eBook.

- ^ a b Built under the administration of Lycurgus, Smith, Sir William, ed. (1859). "Philon, A very eminent architect at Athens". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Vol. III. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. p. 314.. E. A. Gardner, op.cit. p. 557, observes that it "is perhaps known to us more in detail than any other lost monument of antiquity." It was to hold the rigging of the galleys; and was so contrived that all its contents were visible from a central hall, and so liable to the inspection of the Athenian democracy. Philon's arsenal was destroyed by the forces of Lucius Cornelius Sulla in the Roman conquest of Athens in 86 BC.

- ^ Ian Jenkins (2006). Greek Architecture And Its Sculpture. Harvard University Press. pp. 118–126. ISBN 978-0-674-02388-8. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ^ Jeffrey M. Hurwit (2000). The Athenian Acropolis: History, Mythology, and Archeology from the Neolithic Era to the Present. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42834-3.

- ^ Cf. O. W. Reinmuth (1971). The Ephebic Inscriptions of the Fourth Century B.C. Leiden Brill. pp. passim.

- ^ Cf. An Introduction to Greek Epigraphy, Cambridge University Press – (undated, no author cited) Googlebook; see also Ancient Athens, Haskell House Publ., 1902 (no author cited) Googlebook

- ^ Cf. Enrica Culasso Gastaldi (2004). Le prossenie ateniesi del IV secolo a.C.: gli onorati asiatici (Fonti e studi di storia antica, 10). Alessandria: Edizioni dell'Orso. pp. passim.

- ^ Cf. int. al., Joseph Veach Noble (1988). The Techniques of Painted Attic Pottery. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0500050477.; Martin Robinson (1992). The Art of Vase-Painting in Classical Athens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 41–43. ISBN 978-0521338813.

- ^ Cf. P. Botteri; G. Fangi (2003). The Ancyra Project: the Temple of Augustus and Rome. Ankara: ISPRS Archives, volume XXXIV part 5/W12 Commission V. pp. 84–88.; see also The Parian chronicle, or The chronicle of the Arundelian marbles; with a dissertation concerning its authenticity by Joseph Robertson 1788, from the Internet Archive.

- ^ Cf. int. al. the interesting Epitaph of Seikilos by C. V. Palisca & J. P. Burkholder, 2006.

- ^ Ecker, Avner; Leibner, Uzi (2025). "'Diocletian oppressed the inhabitants of Paneas' (ySheb. 9:2): A New Tetrarchic boundary stone from Abel Beth Maacah". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 157 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1080/00310328.2024.2435218.

- ^ Marom, Roy (2025). "A Toponymic Reassessment of the Abil al-Qamḥ Diocletianic Boundary Stone: Identifying Golgol at al-Zūq al-Fauqānī". Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology. 8: 51–59.

- ^ A mere list of such initials and abbreviations occupies 68 pages in René Cagnat's Cours d'épigraphie Latine (repr. 1923). A selection is included in Wikipedia's "List of classical abbreviations".

- ^ It reads: Victo(riae) Fl(avius) P/rimus cur(ator) / tur(mae) Maxi/mini.

- ^ Cf. E.R. Graser (1940). T. Frank (ed.). An Economic Survey of Ancient Rome Volume V: Rome and Italy of the Empire. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press – esp. "A text and translation of the Edict of Diocletian".

- ^ a b Francis Haverfield, "Roman Authority" in S. R. Driver, D. G. Hogarth, F. L. Griffith, et al. Authority and Archaeology, Sacred and Profane: Essays on the Relation of Monuments to Biblical and Classical Literature, Ulan Press (repr. 2012), p. 314.

- ^ a b Cf. Edward Courtney (1995). MUSA Lapidaria: A Selection of Latin Verse Inscriptions. Atlanta: Scholars Press.

- ^ Cf. Arthur E. Gordon, Latin Epigraphy, University of California Press, 1983, Introd., pp. 3–6.

- ^ a b c Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3. Archived from the original on 2 July 2023. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: ca. 150 BCE – 100 CE. BRILL Academic. p. 260. ISBN 978-90-04-15537-4. Archived from the original on 2 July 2023. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ^ Court, Christopher (1996). "The Spread of Brahmi Script into Southeast Asia". In Daniels, Peter T. (ed.). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7. Archived from the original on 29 March 2024. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ^ Masica, Colin P. (1993). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2. Archived from the original on 1 February 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

External links

[edit]- "EAGLE: Europeana Network of Ancient Greek and Latin Epigraphy". EAGLE project. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- Bodel, John (1997–2009). "U.S. Epigraphy Project". Brown University. Archived from the original on 7 April 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- Centre d'études épigraphiques et numismatiques de la faculté de Philosophie de l'Université de Beograd. "Inscriptions de la Mésie Supérieure" (in French). Archived from the original on 25 July 2009. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- "Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents". Oxford: Oxford University. 1995–2009. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- Clauss, Manfred. "Epigraphik-Datenbank Clauss-Slaby (EDCS)" (in German, Italian, Spanish, English, and French). Archived from the original on 25 August 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- "EAGLE: Electronic Archive of Greek and Latin Epigraphy" (in Italian). Federazione Internazionale di Banche dati Epigrafiche presso il Centro Linceo Interdisciplinare "Beniamino Segre" – Roma. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- "Epigraphische Datenbank Heidelberg (EDH)". 1986–2012. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- International Federation of Epigraphic Databases. "Epigraphic Database Roma (EDR)" (in Italian). Association Internationale d'Épigraphie Grecque et Latine – AIEGL. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- International Federation of Epigraphic Databases. "Epigraphic Database Bari: Documenti epigrafici romani di committenza cristiana – Secoli III – VIII" (in Italian). Association Internationale d'Épigraphie Grecque et Latine – AIEGL. Archived from the original on 25 January 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- "Hispania Epigraphica Online (HEpOl)" (in Spanish and English). Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- Greek Epigraphy Project, Cornell University; Epigraphical Center; Ohio State University (2009). "Searchable Greek Inscriptions". Packard Humanities Institute. Archived from the original on 10 December 2009. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- The Institute for Ancient History (1993–2009). "Epigraphic database for ancient Asia Minor". Universität Hamburg. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- Reynolds, Joyce; Roueché, Charlotte; Bodard, Gabriel (2007). Inscriptions of Aphrodisias (IAph2007). London: King's College. ISBN 978-1-897747-19-3.

- "The American Society for Greek and Latin Epigraphy (ASGLE)". Case Western Reserve University. Archived from the original on 30 March 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- "Ubi Erat Lupa" (in German). Universität Salzburg. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- Poinikastas: Epigraphic Sources For Early Greek Writing, Oxford University

- Current Epigraphy a journal of news and short reports on inscriptions

- The Epigraphic Society Formed in 1974 by Professor Barry Fell of Harvard University and Professor Norman Totten of Bentley College, its journal, the Epigraphic Society Occasional Papers (ESOP), is shelved by numerous universities and research institutions worldwide.

- Signs of Life a Virtual Exhibition on Epigraphy, presenting several aspects of it with examples.

- Edwin Whitfield Fay (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.