Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Neosauropoda

View on Wikipedia

| Neosauropods Temporal range: Early Jurassic - Late Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

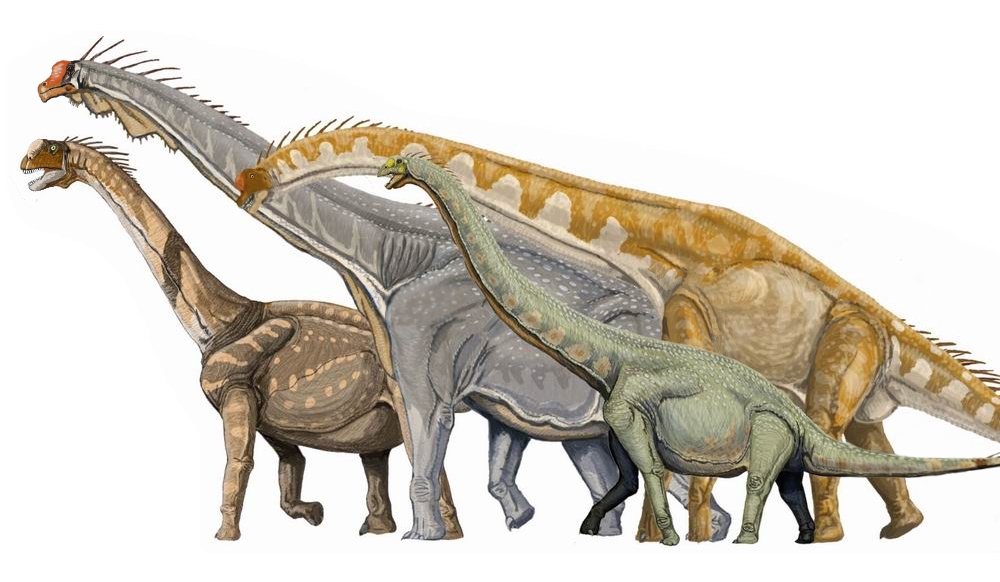

| Several macronarian sauropods | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Clade: | †Eusauropoda |

| Clade: | †Neosauropoda Bonaparte, 1986 |

| Subgroups | |

Neosauropoda is a clade within Dinosauria, coined in 1986 by Argentine paleontologist José Bonaparte and currently described as Saltasaurus loricatus, Diplodocus longus, and all animals directly descended from their most recent common ancestor. The group is composed of two subgroups: Diplodocoidea and Macronaria. Arising in the early Jurassic and persisting until the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, Neosauropoda contains the majority of sauropod genera, including genera such as Apatosaurus, Brachiosaurus, and Diplodocus.[1] It also includes giants such as Argentinosaurus, Patagotitan and Sauroposeidon, and its members remain the largest land animals ever to have lived.[2]

When Bonaparte first coined the term Neosauropoda in 1986, he described the clade as comprising "end-Jurassic" sauropods. While Neosauropoda does appear to have originated at the end of the Jurassic period, it also includes members throughout the Cretaceous. Neosauropoda is currently delineated by specific shared, derived characteristics rather than the time period in which its members lived.[3] The group was further refined by Upchurch, Sereno, and Wilson, who have identified thirteen synapomorphies shared among neosauropods.[4] As Neosauropoda is a subgroup of Sauropoda, all members also display basic sauropod traits such as large size, long necks, and columnar legs.[5]

History of discovery

[edit]Paleontologist Richard Owen named the first sauropod, Cetiosaurus, in 1841. Due to the fragmentary evidence, he originally believed it to be a type of massive crocodile. Cetiosaurus has at times been classified as a basal member of Neosauropoda, which would make it the first member of this group discovered.[6] Most current research, however, places Cetiosaurus outside Neosauropoda as a sister taxon.[7] The first dinosaurs discovered which are conclusively known to fall within Neosauropoda were Apatosaurus and Camarasaurus, both found in North America in 1877, and Titanosaurus discovered the same year in India.[8] There were other sauropods besides Cetiosaurus which were described before the 1870s, but most were known from only very fragmentary material and none were described in sufficient detail that they may conclusively be classified as neosauropods. A great number of neosauropod skeletons were unearthed in western North America during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, primarily Apatosaurus, Camarasaurus, and Diplodocus.[6]

Evolution

[edit]Sauropodomorpha, of which Neosauropoda is a subclade, first arose in the late Triassic. Around 230 million years ago, animals such as Eoraptor, the most basal known member of Dinosauria and also Saurischia, already displayed certain features of the Sauropod group.[9] These derived characters began to distinguish them from Theropoda.[10] There were several major trends in the evolution of sauropodomorphs, most notably increased size and elongated necks, both of which would reach their culmination in neosauropods. Basal members of Sauropodomorpha are often collectively termed prosauropods, although this is likely a paraphyletic group, the exact phylogeny of which has not been conclusively determined. True sauropods appear to have developed in the Upper Triassic, with trackways from a basal member known as the ichnogenus Tetrasauropus being dated to 210 million years ago.[11] At this point, the forelimbs had lengthened to at least 70% of the length of the hindlimbs and the animals moved from a facultatively bipedal to a quadrupedal posture. The limbs also rotated directly under the body, in order to better support the weight of the steadily increasing body size.[12] During the Middle Jurassic, sauropods began to display increased neck length and more specialized dentition. They also developed a digitigrade posture in the hindlimbs, in which the heel and proximal metatarsals were raised completely off the ground. The foot also became more spread out, with the ends of the metatarsals no longer in contact with each other. These developments have been used to distinguish a new clade among sauropods, termed Eusauropoda.[13]

Neosauropoda diverged from the rest of Eusauropoda in the Early Jurassic and quickly became the dominant group of large herbivores. The earliest known neosauropod is Lingwulong, a dicraeosaurid from the late Early Jurassic or early Middle Jurassic of China.[14] Diplodocid and brachiosaurid members of the group composed the greater portion of neosauropods during the Jurassic, but they began to be replaced by titanosaurs in most regions through the Cretaceous period.[3] By the late Cretaceous, titanosaurs were the dominant group of neosauropods, especially on the southern continents. In North America and Asia, much of their role as large herbivores had been supplanted by hadrosaurs and ceratopsians, although they remained in smaller numbers all the way until the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction.[15]

Description

[edit]In addition to the basic features of sauropods in general and eusauropods in particular, neosauropods share certain derived features, which have been used to distinguish them as a cohesive group. In their 1998 paper, Sereno and Wilson identified thirteen characteristics that distinguish neosauropods from more basal sauropods (described below).[16]

Skull

[edit]Neosauropods display a large opening in the skull located ventral to the antorbital fenestra, known as the preantorbital fenestra. This opening is differentially shaped among various species of neosauropods, and it has been proposed that the preanorbital fenestra is reduced or closes up completely in adult Camarasaurus, but is otherwise ubiquitous among neosauropods.[17] The ventral process of the postorbital bone is broader when viewed from the anterior when compared to the width when viewed from the lateral side.[18] Neosauropods lack a point of contact between the jugal bone and the ectopterygoid arch. Instead, the ecterpteryoid arch abuts the maxilla, anterior to the jugal. The external mandibular fenestra, present in prosauropods and some basal sauropods, is entirely closed.[19]

Dentition

[edit]Neosauropods lack denticles on the majority of their teeth. In some species, including Camarasaurus and Brachiosaurus, they are retained on the most posterior teeth, but most advanced forms have lost them entirely. Certain members of the subgroup Titanosauria have ridges along their posterior teeth, but these are not large enough to be considered denticles of a form similar to those found in more basal sauropods.[19]

Manus

[edit]The number of carpal bones in neosauropods is reduced to two or fewer. This continues a trend of successive carpal loss seen in the evolutionary record. Early dinosaurs such as Eoraptor tend to have four distal carpals. In prosauropods, this is reduced to three and the proximal carpals are usually lost or shrink in size. Basal sauropods also tend to have three carpal bones, but they are more block-like than in earlier forms. Neosauropods further reduce this number to two, and in some cases even fewer.[19]

The metacarpals of neosauropods are bound together, allowing a digitigrade posture with the manus raised up off the ground. Prosauropods and basal sauropods have metacarpals which are articulated at the base, but this is further developed in neosauropods such that the articulation continues down the shafts. The ends of the metacarpals also form a tight arch with wedge-shaped shafts fitting closely together.[20]

Tibia

[edit]The tibia of neosauropods has a subcircular proximal end. The transverse and anteroposterior dimensions of the proximal end are also equal or nearly so in neosauropods, whereas the transverse dimension of the tibia is always shorter than the anteroposterior dimension in prosauropods, theropods, and those basal sauropods for which evidence is available.[21]

Ankle

[edit]The astragalus displays two unique features in neosauropods. When viewed from the proximal side, the ascending process extends to the posterior end of the astragalus. The astragalus is also wedge shaped when viewed from the anterior side due to a reduction in the medial portion.[21]

Skin

[edit]

Among macronarians, fossilized skin impressions are only known from Haestasaurus, Tehuelchesaurus and Saltasaurus. Haestasaurus, the first dinosaur known from skin impressions, preserved integument over a portion of the arm around the elbow joint approximately 19.5 by 21.5 cm (7.7 by 8.5 in) in area. Small, hexagonal scales are preserved, ranging from 1–2.5 cm (0.39–0.98 in) in diameter. It has been suggested that the convex surface of the scales was from the internal size of the integument, facing the bones, but this has been rejected as the convex surfaces are preserved on the outside of Saltasaurus and titanosaur embryos.[22] Dermal impressions are more widespread in the material of Tehuelchesaurus, where they are known from the areas of the forelimb, scapula and torso. There are no bony plates or nodules, to indicate armour, but there are several types of scales. Skin associated with the scapular blade is the largest, arranged in rosettes (spiral formations) with a smooth, hexagonal shape. These largest tubercles are 2.5–3 cm (0.98–1.18 in), surrounded by smaller 1.5–2 cm (0.59–0.79 in) scales. The other type of scales are very small, only between 1 and 4 mm (0.039 and 0.157 in) in diameter, and are preserved in small fragments from the forelimb and thoracic region. These skin types are overall more similar to those found in diplodocids and Haestasaurus than in the titanosaur embryos of Auca Mahuevo.[23] As the shape and articulation of the preserved tubercles in these basal macronarians are similar in other taxa where skin is preserved, including specimens of Brontosaurus excelsus and intermediate diplodocoids, such dermal structures are probably widespread throughout Neosauropoda.[22]

Classification

[edit]Phylogeny

[edit]José Bonaparte originally described Neosauropoda as comprising members of four sauropod groups: Dicraeosauridae, Diplodocidae, Camarasauridae, and Brachiosauridae.

Upchurch's 1995 paper on sauropod phylogeny proposed the current definition for Diplodocoidea, which was then classified as a subgroup of Titanosauridae. Cetiosaurus was linked to Neosauropoda by a trichotomy, as the genus' fragmentary and often dubious description meant that it could be placed as a sister taxon to the Titanosauridae-Diplodocoidae clade, the Brachiosauridae-Camarasauridae clade, or Neosauropoda as a whole.[24]

From Upchurch 1995:[25]

| Sauropoda |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 1998, Sereno and Wilson published a cladistic analysis of the sauropod family which proposed Macronaria as a new taxon containing Camarasaurus, Haplocanthosaurus, and Titanosauriformes. Titanosauriformes was considered to include Brachiosaurus, Saltasaurus, and all descendants of their most recent common ancestor. This represented a significant deviation from Upchurch's 1995 phylogeny as well as much of the traditional understanding of neosauropod taxonomy. Conventional cladistics had long considered titanosaurs and diplodocoids to be more closely related, with brachiosaurids and camarasaurids together forming a sister taxon.[26]

From Sereno and Wilson 1998:[27]

Subgroups

[edit]Neosauropoda is divided into two major subgroups: Macronaria and Diplodocoidea. These taxa are differentiated on the basis of several morphological features.

From Upchurch et al. 2004:[28]

| Neosauropoda | |

Macronaria

[edit]Macronaria is defined as all neosauropods more closely related to Saltasaurus loricatus than Diplodocus longus. This classification was introduced by Wilson and Sereno in 1998. Macronaria comes from the Latin for "large nose," referring to the large external naris.[29] The subgroup Titanosauriformes comprises all sauropods descended from the common ancestor of Brachiosaurus and Saltasaurus. Macronaria is an exceedingly diverse clade, with members ranging in size from anywhere between six and thirty-five meters in length and sporting a broad array of body shapes. Some synapomorphies which have been used to characterize macronarians include flared neural spines on the dorsal vertebrae and nearly coplanar ischial distal shafts.[30]

Diplodocoidea

[edit]Diplodocoidea is defined as all neosauropods more closely related to Diplodocus longus than Saltasaurus loricatus. The group is named after Diplodocus, its best known member. Other prominent dinosaurs contained in this clade include Apatosaurus, Supersaurus, and Brontosaurus. Diplodocoids are distinguished by a unique head shape, which displays certain highly derived features when compared to other sauropods. The teeth are located entirely anterior to the antorbital fenestra and the snout is especially broad. In some rebbachisaurids, this is taken to such an extreme that the teeth are packed into a row along the transverse portion of the jaw. Several unique features are also noted in the tails of certain diplodocoids. Among the diplodocids, there was a marked increase in the number of caudal vertebrae. Most sauropods have between forty and fifty caudal vertebrae, but in diplodocids this number jumps to eighty or more. In addition, the most distal vertebrae develop a biconvex shape and together form a long, bony rod at the end of the tail, often referred to as a "whiplash tail." Increased caudal count and a whiplash tail may be features shared by all members of the Diplodocoid group, but, due to a scarcity of evidence, this has yet to be proven.[29]

References

[edit]- ^ Rogers, Kristina Curry, and Jeffrey A. Wilson. The Sauropods: Evolution and Paleobiology. Berkeley: U of California, 2005.

- ^ Souza, L. M. De, and R. M. Santucci. "Body Size Evolution in Titanosauriformes (Sauropoda, Macronaria)." Journal of Evolutionary Biology J. Evol. Biol. 27.9 (2014): 2001-012.

- ^ a b Rogers, et al. 2005

- ^ Wilson, Jeffrey A., and Paul C. Sereno. "Early Evolution and Higher-Level Phylogeny of Sauropod Dinosaurs." Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 18.Sup002 (1998): 1-79.

- ^ Wilson, Jeffreya. "Sauropod Dinosaur Phylogeny: Critique and Cladistic Analysis." Zool J Linn Soc Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 136.2 (2002): 215-75.

- ^ a b Taylor, Mike P. "The Evolution of Sauropod Dinosaurs from 1841 to 2008." 2008.

- ^ D.T. Ksepka and M.A. Norell, 2010, "The Illusory Evidence for Asian Brachiosauridae: New Material of Erketu ellisoni and a Phylogenetic Reappraisal of Basal Titanosauriformes", American Museum Novitates 3700: 1-27

- ^ Taylor 2008

- ^ Alcober, Oscar A.; Martinez, Ricardo N. (2010). "A new herrerasaurid (Dinosauria, Saurischia) from the Upper Triassic Ischigualasto Formation of northwestern Argentina". ZooKeys (63): 55–81. Bibcode:2010ZooK...63...55A. doi:10.3897/zookeys.63.550. PMC 3088398. PMID 21594020.

- ^ Sereno, Paul; Martinez Ricardo; Alcober, Oscar. 2012. Osteology of Eoraptor lunensis (Dinosauria, Sauropodomorpha). J Vertebr Paleontol. 32(Suppl 1):83–179.

- ^ Rogers, et al. 2005. p. 23

- ^ Rogers, et al. 2005 p. 23

- ^ Rogers, et al. 2005 p. 27-28

- ^ Xing Xu; Paul Upchurch; Philip D. Mannion; Paul M. Barrett; Omar R. Regalado-Fernandez; Jinyou Mo; Jinfu Ma; Hongan Liu (2018). "A new Middle Jurassic diplodocoid suggests an earlier dispersal and diversification of sauropod dinosaurs". Nature Communications. 9 (1) 2700. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.2700X. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-05128-1. PMC 6057878. PMID 30042444.

- ^ Lehman, T. M., 2001, Late Cretaceous dinosaur provinciality: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press.

- ^ Sereno and Wilson 1998 p. 46-49

- ^ Sereno and Wilson 1998 p. 46

- ^ Sereno and Wilson 1998 p.46-47

- ^ a b c Sereno and Wilson 1998 p. 47

- ^ Sereno and Wilson 1998 p. 48

- ^ a b Sereno and Wilson 1998 p. 49

- ^ a b Upchurch, P.; Mannion, P.D.; Taylor, M.P. (2015). "The Anatomy and Phylogenetic Relationships of "Pelorosaurus" becklesii (Neosauropoda, Macronaria) from the Early Cretaceous of England". PLOS ONE. 10 (6) e0125819. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1025819U. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0125819. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4454574. PMID 26039587.

- ^ Giménez, O. del V. (2007). "Skin impressions of Tehuelchesaurus (Sauropoda) from the Upper Jurassic of Patagonia". Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales. 9 (2): 119–124. doi:10.22179/revmacn.9.303.

- ^ Upchurch P. 1995. The evolutionary history of sauropod dinosaurs. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London Ser. B 349:365-90.

- ^ Upchurch 1995. p. 369

- ^ Sereno and Wilson 1998.

- ^ Sereno and Wilson 1998. p. 54

- ^ Upchurch P, Barrett PM, Dodson P (2004). "Sauropoda". In Weishampel DB, Dodson P, Osmólska H (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). University of California Press. p. 316. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ^ a b Rogers et al. 2005

- ^ Sereno and Wilson 1998

External links

[edit]- Vertebrate Paleontology (University of Bristol)

- TaxonSearch entry for Neosauropoda

Neosauropoda

View on GrokipediaHistory of Discovery

Early Finds

The earliest potential neosauropod fossils were described in 1841 by Richard Owen, who named the genus Cetiosaurus based on fragmentary remains including vertebrae and limb bones collected from the Inferior Oolite Formation near Chipping Norton in Oxfordshire, England.[4][5] Owen interpreted these specimens as belonging to a gigantic extinct saurian reptile, specifically misclassifying it as a large aquatic predator akin to a marine crocodile or cetacean, reflected in the etymology "whale lizard" (Cetus for whale and sauros for lizard).[6][7] No species epithet was assigned at the time, and Owen's original description lacked detailed measurements or illustrations, focusing instead on the bones' robust proportions suggestive of an immense body size exceeding any known contemporary reptile.[4] A major advance came during the "Bone Wars" rivalry between American paleontologists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope, when Marsh announced the discovery of more complete neosauropod skeletons in 1877 from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation in Colorado and Wyoming, USA.[8] Marsh named Apatosaurus ajax that year based on an incomplete juvenile skeleton (YPM 1860) featuring a long neck, tail, and pillar-like limbs, marking the first well-substantiated neosauropod material and solidifying sauropods' recognition as a distinct group of terrestrial dinosaurs rather than aquatic forms.[8][9] Shortly thereafter, in 1878, Marsh described Diplodocus from additional Morrison Formation fossils first collected in 1877, including elongated cervical vertebrae measuring up to 1 meter in length, which highlighted the clade's characteristic extreme neck elongation.[8] These finds, excavated amid intense competition, provided the foundational specimens that differentiated neosauropods from other reptiles through their quadrupedal stance and herbivorous adaptations.[10] These early discoveries sparked initial debates on neosauropod posture, particularly the orientation of the neck and overall body support. Owen's aquatic reconstruction implied a sprawling, semi-aquatic gait with a low-slung body, while Marsh's terrestrial interpretations emphasized pillar-like limbs akin to elephants, supporting a horizontal trunk but with uncertainty over neck elevation.[11] Marsh's original illustrations in his 1877 description of Apatosaurus depicted the neck in a nearly straight, horizontal pose relative to the body, based on articulated vertebrae showing gentle curvature and centrum lengths of approximately 0.5–0.8 meters for mid-cervicals.[11] Similarly, his 1878 Diplodocus diagrams illustrated a sub-horizontal neck posture, with measurements of neural arches indicating limited vertical flexion, fueling discussions on whether such giants browsed with elevated or level heads.[11] Cetiosaurus was later positioned phylogenetically as a basal eusauropod based on these early specimens.Naming and Definition

The clade Neosauropoda was coined in 1986 by Argentine paleontologist José Bonaparte to designate a group of advanced sauropod dinosaurs, initially conceptualized as an evolutionary grade of advanced Upper Jurassic sauropods, including diplodocoids and macronarians but excluding more basal forms like cetiosaurids.[12] Bonaparte's original formulation did not include titanosaurs and lacked a formal phylogenetic definition, instead relying on morphological distinctions to separate "neosauropods" from earlier sauropods.[12] Upchurch (1995) proposed diagnostic traits for Neosauropoda, including the presence of a preantorbital fenestra—a large opening in the skull ventral to the antorbital fenestra—and a reduced number of carpal bones, typically two or fewer, continuing a trend of forelimb simplification observed in sauropod evolution.[13] These features were seen as shared derived characters (synapomorphies) marking the transition to more derived sauropod body plans, with examples including diplodocids like Diplodocus and macronarians like Camarasaurus.[13] Subsequent refinements to the definition and diagnosis occurred through cladistic analyses. Paul Upchurch in 1995 provided an early phylogenetic context, emphasizing Neosauropoda's monophyly within Sauropoda and incorporating additional synapomorphies such as modifications to vertebral pneumaticity.[12] Further elaboration by Jeffrey A. Wilson and Paul C. Sereno in 1998 established a node-based phylogenetic definition: the most recent common ancestor of Saltasaurus loricatus and Diplodocus longus, plus all its descendants.[14] Their work, building on Upchurch's framework, added synapomorphies like the position of the subnarial foramen separated from the anterior maxillary foramen by a narrow bony isthmus, enhancing the clade's diagnostic robustness.[14]Recent Advances

In the early 20th century, the Tendaguru Formation in southern Tanzania emerged as a pivotal site for neosauropod discoveries during the German Tendaguru Expedition (1909–1913), led by Werner Janensch, which unearthed multiple partial skeletons of the brachiosaurid Brachiosaurus brancai (now classified as Giraffatitan brancai), including well-preserved axial and limb elements that highlighted the clade's extreme long-necked morphology.[15] These finds, representing some of the largest known sauropods at the time, were systematically excavated from Late Jurassic sediments but sparked export controversies due to the colonial context, with thousands of tons of fossils shipped to Berlin's Museum für Naturkunde, many of which were later destroyed during World War II bombings, limiting subsequent study.[16] The expedition's efforts, building on earlier reports from 1906, established Tendaguru as a key African locality for understanding neosauropod paleobiogeography in Gondwana.[17] The 21st century has seen a global expansion in neosauropod fossil recoveries, particularly from South America, exemplified by the 2014 discovery of Patagotitan mayorum in Chubut Province, Argentina, from the Early Cretaceous Cerro Barcino Formation. This titanosaur, described in 2017 from over 50 bones representing at least six individuals, provided one of the most complete giant neosauropod skeletons known, with estimates of lengths exceeding 37 meters and masses around 70 tons, underscoring rapid growth rates in somphospondylans.[18] Further advancing titanosaur diversity, a 2024 study of the Portezuelo Formation (upper Turonian–lower Coniacian) in Neuquén Province, Patagonia, analyzed new specimens (MCF-PVPH 916 and 917), including caudal vertebrae, revealing basal somphospondylians closely allied to Malarguesaurus and potentially representing new taxa, thus expanding the known non-titanosaurian neosauropod assemblage in Late Cretaceous Gondwana.[19] Recent 2025 research has refined neosauropod understanding through reappraisals and new finds in Asia. The re-description of Liaoningotitan sinensis from the Lower Cretaceous Yixian Formation in Liaoning Province, China, confirmed its placement within Euhelopodidae (Titanosauriformes, a macronarian subclade) via updated phylogenetic analysis, with the holotype estimated at approximately 10 meters in length as an immature individual based on unfused sacral vertebrae, suggesting potential for greater mature size.[20] Complementing this, the description of Jinchuanloong niedu from the Middle Jurassic Xinhe Formation in Gansu Province, northwestern China, represents a non-neosauropod eusauropod positioned as sister to Turiasauria + Neosauropoda, filling stratigraphic gaps in early neosauropod evolution with a subadult specimen estimated at about 10 meters long, inferred from unfused vertebrae.[21] These updates, incorporating modern comparative methods, highlight ongoing technological enhancements in fossil preparation and analysis since Bonaparte's 1986 naming of Neosauropoda.[20]Evolution

Origins

Neosauropoda emerged during the Early to Middle Jurassic, representing a key evolutionary advancement among sauropod dinosaurs through innovations such as the hyposphene-hypantrum articulations in the posterior dorsal and anterior caudal vertebrae, which enhanced spinal stability and load-bearing capacity compared to more basal sauropods.[2] These features distinguished neosauropods from earlier forms like vulcanodontids, marking a transition toward the diverse, long-necked giants that dominated later Mesozoic ecosystems. Recent discoveries, such as fossils of the oldest known diplodocoid from the Middle Jurassic of India, suggest that India may have been a major center for neosauropod radiation in Gondwana.[22] The earliest known neosauropod is Lingwulong shenqi, discovered in the lower Middle Jurassic Yanan Formation at Ciyaopu in Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, northwestern China, dated to approximately 174 million years ago (late Toarcian to Bajocian stages).[23] This diplodocoid sauropod is represented by multiple partial skeletons, including skulls, vertebrae, and limb elements, recovered from fluviolacustrine deposits indicative of a semi-lacustrine habitat with fluvial influences.[24] Lingwulong exhibits transitional traits, including shallowly amphicoelous caudal centra that retain primitive features while incorporating advanced diplodocoid characteristics like a co-ossified skull roof and large supratemporal fenestrae, bridging basal sauropods and later neosauropod clades.[23] In contrast, basal sauropods such as Vulcanodon karibaensis from the uppermost Forest Sandstone of Zimbabwe, dated to around 183 million years ago (early Toarcian), lack hyposphene-hypantrum articulations and display more generalized vertebral morphology without the specialized load-bearing adaptations of neosauropods.[2] The origin of Neosauropoda likely occurred in rift basins spanning Gondwana and Laurasia amid the early stages of Pangea breakup, with fossil evidence suggesting divergence from basal sauropods around 190–180 million years ago.[23] Recent discoveries, such as the non-neosauropod eusauropod Jinchuanloong niedu from the Middle Jurassic Xinhe Formation in Gansu Province, China, further underscore the early diversification of advanced sauropods in Asia.[21]Diversification Patterns

Neosauropods underwent a major radiation during the Late Jurassic, particularly in floodplain environments of Laurasia, where diplodocoids and brachiosaurids achieved high diversity and gigantism. In the Morrison Formation of North America, approximately 10-13 genera of sauropods, predominantly neosauropods such as Apatosaurus, Diplodocus, Brachiosaurus, and Camarasaurus, coexisted, representing a peak in taxonomic richness driven by niche partitioning in resource-limited settings.[25][26] This diversification coincided with body sizes reaching 25-30 meters in length for diplodocids and brachiosaurids, facilitated by adaptations for high browsing and efficient herbivory in fern- and cycad-dominated ecosystems.[3] By the Early Cretaceous, neosauropod faunas shifted dramatically, with diplodocoids declining sharply in Laurasia and nearly disappearing globally, while titanosaurs rose to dominance in Gondwanan continents. This transition reflected ecological partitioning, as the spread of angiosperms from the Early Cretaceous onward altered vegetation structure, enabling titanosaurs to exploit new low- to mid-height browsing niches previously occupied by other herbivores.[27][28] In South America, titanosaurs like Argentinosaurus huinculensis exemplified this radiation, attaining lengths of up to 35 meters and masses of 70-100 tons, underscoring their evolutionary success in southern floodplains and coastal plains.[18] Neosauropods persisted until the end-Cretaceous extinction, with titanosaurs such as Alamosaurus sanjuanensis surviving in North America during the Maastrichtian, marking a reintroduction of large sauropods to the continent after a prolonged absence. In Gondwana, recent discoveries from the Late Cretaceous Portezuelo Formation in Patagonia reveal ongoing diversity, including non-titanosaurian titanosauriforms coexisting with derived titanosaurs like Futalognkosaurus dukei, indicating sustained neosauropod persistence in southern latitudes.[19] The Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) event at 66 million years ago, triggered by the Chicxulub asteroid impact and exacerbated by Deccan Traps volcanism, led to their extinction through global cooling, habitat disruption, and food chain collapse.[29]Description

Cranial Features

The skulls of neosauropods are characterized by a generally box-like morphology, with the external nares positioned dorsally on the skull roof, forming large openings that reflect adaptations for their elongate necks and terrestrial lifestyle.[3] This configuration contrasts with more anteriorly placed nares in basal sauropods and underscores the clade's evolutionary shift toward efficient aerial intake in elevated feeding positions. A defining cranial synapomorphy of Neosauropoda is the presence of a preantorbital fenestra, a large opening located ventral to the antorbital fenestra and at the base of the ascending process of the maxilla; this feature is absent or much smaller in basal sauropods and serves to lighten the skull while accommodating expanded nasal passages. The antorbital fenestra itself is relatively small compared to that in non-sauropod sauropodomorphs, and the quadratojugal bone is reduced in size, contributing to a more streamlined posterior skull region that facilitates lateral jaw mobility. These fenestral modifications, combined with the loss of the jugal-ectopterygoid contact, represent key innovations that distinguish neosauropods from their ancestors. Computed tomography (CT) scans of neosauropod braincases, such as that of Diplodocus, reveal an expanded olfactory region with relatively large olfactory bulbs and tracts, indicating enhanced olfactory capabilities that likely aided in foraging for dispersed vegetation over vast areas. This sensory adaptation is evident in the increased olfactory ratio (the relative size of the olfactory bulbs to the cerebral hemispheres) within Neosauropoda, surpassing that of many basal sauropodomorphs and suggesting a reliance on smell for detecting food sources.[30] Cranial morphology varies notably between neosauropod subclades, with diplodocoids exhibiting markedly elongated snouts that extend anteriorly beyond the eye region, forming a narrow, horse-like profile suited to precise, lateral sweeping of foliage.[31] In contrast, macronarians possess deeper, more robust skulls with a U-shaped or boxier snout profile, as seen in taxa like Camarasaurus, which supported broader browsing strategies. Adult neosauropod skulls typically range from 30 to 80 cm in length, scaling with body size and reflecting the clade's diverse ecological niches.[32] These variations integrate with the feeding apparatus, where snout shape influences the positioning of simple, peg-like dentition for cropping vegetation.[33]Postcranial Skeleton

The postcranial skeleton of neosauropods is characterized by an elongated axial column adapted for gigantism and efficient locomotion, with the neck comprising 12 to 15 cervical vertebrae that exhibit high elongation indices, often exceeding 5 in length relative to height, facilitating extensive reach for high browsing.[34] These vertebrae display extensive pneumaticity, evidenced by complex laminae, fossae, and internal chambers, which are interpreted as traces of diverticula from cervical and abdominal air sacs, reducing skeletal mass while supporting a bird-like respiratory system.[35] The tail, serving primarily for balance during quadrupedal progression, includes up to 80 caudal vertebrae in some taxa such as diplodocids, with a corresponding series of up to 50 chevrons forming a robust haemal arch system that anchors caudal musculature and stabilizes the long counterbalance.[36] The appendicular skeleton supports a fully quadrupedal, pillar-like posture, with forelimbs nearly equal in length to hindlimbs, as indicated by humerus-to-femur length ratios typically ranging from 0.8 to 1.0 across neosauropod clades, correlating with body masses of 20 to 80 metric tons in large species such as diplodocids and titanosaurs.[37] The manus is digitigrade, featuring a semi-tubular arrangement of five robust, tightly appressed metacarpals forming a U-shaped colonnade in proximal view, with only 2 to 3 ossified carpals preserved in most specimens and prominent claws on digits I and II (with reduced unguals on III and vestigial phalanges on IV and V).[38] The tibia possesses a subcircular proximal articular surface for enhanced stability and is typically 60-80% the length of the femur in neosauropods, contributing to the fully erect limb posture that minimizes muscular effort in weight-bearing.[39] In the hindlimb, the ankle joint reflects adaptations for load distribution, with the astragalus and reduced calcaneum co-ossifying in adults to form a tight crurotarsal articulation that limits rotation while permitting flexion.[40] The pes is semi-digitigrade, with weight borne primarily on digits I-IV via a fleshy heel pad inferred from trackway evidence, and an asymmetrical configuration where the main axis passes through digits II-III for efficient propulsion and stability under immense body mass.[3] These features collectively underscore locomotor adaptations for slow, energy-efficient movement in terrestrial environments, prioritizing stability over speed.[41]Integument

The integument of neosauropods primarily consisted of scaly skin, as evidenced by numerous fossil impressions across the clade, with no confirmed presence of feathers or filamentous structures.[42] In diplodocoids such as Diplodocus, preserved skin patches reveal a diversity of non-overlapping scales, including small, rounded tubercles and larger, irregular polygonal forms, indicating a flexible, non-armored external covering suited to their elongated bodies.[43] These impressions, often from the tail and flanks, show a pebbly texture without osteoderms, contrasting with more derived neosauropod lineages.[44] Among macronarians, particularly derived titanosaurs, the integument included armored elements in the form of osteoderms—small, bony scutes embedded in the dermis—for potential defense against predators. In Saltasaurus loricatus from the Late Cretaceous of Argentina, these osteoderms comprise polygonal plates and ossicles, with histological analysis revealing a cancellous internal structure formed through dermal metaplasia, arranged in clusters along the back and sides.[45] Such armor is absent in earlier or more basal neosauropods, suggesting an evolutionary innovation within lithostrotian titanosaurs.[46] Direct evidence of scale morphology comes from exceptional skin impressions, such as those associated with Haestasaurus becklesii from the Early Cretaceous of England, which preserve small hexagonal scales measuring 1–2.5 cm in diameter alongside vascular patterns visible through laser-stimulated fluorescence imaging.[42] Similarly, impressions from Tehuelchesaurus benitezii in the Late Jurassic of Argentina display tuberculate skin with densely packed small tubercles (approximately 1–2 mm), forming a rough, non-imbricating surface on the thoracic region.[47] These features indicate a predominantly reptilian-style integument across neosauropods, likely facilitating thermoregulation and protection while attaching to the underlying pneumatic postcranial skeleton.[42] Coloration inferences for neosauropods remain speculative due to the rarity of melanosome preservation, but preserved skin textures and ecological context suggest countershading patterns with mottled brown-gray hues for camouflage in forested or riverine habitats, akin to modern large herbivores.[44] No melanosome-based direct evidence exists for neosauropods, distinguishing them from feathered theropods where such structures confirm iridescent or pigmented displays.[42]Classification

Definition

Neosauropoda is a node-based clade within Sauropoda, defined as the most recent common ancestor of Diplodocus longus and Saltasaurus loricatus and all of its descendants. The clade was originally proposed by José F. Bonaparte in 1986 to encompass advanced, predominantly Late Jurassic sauropods, but it was refined and formally defined in 1998 by Jeffrey A. Wilson and Paul C. Sereno to include a broader array of derived forms. Key diagnostic apomorphies of Neosauropoda include the presence of a preantorbital fenestra—a large opening in the maxilla ventral to the antorbital fenestra—and the hyposphene-hypantrum articulation system in the dorsal vertebrae, which consists of a hypantrum (a fossa below the postzygapophysis) and a hyposphene (a process above the neural canal) that interlock adjacent vertebrae. Another core synapomorphy is the reduction in length of the sacral ribs relative to those in basal sauropods, contributing to a more compact sacrum. These traits distinguish Neosauropoda from basal eusauropods, such as those exhibiting spatulate teeth or other plesiomorphic features. Neosauropoda encompasses the vast majority of described sauropod taxa and exhibits a temporal range from the Middle Jurassic (around 174 Ma) to the Late Cretaceous (66 Ma), excluding basal forms like Antetonitrus.[48] This clade dominates sauropod diversity after the Early Jurassic, with representatives in nearly all major continental faunas until the end-Cretaceous extinction.[48]Phylogeny

Neosauropoda represents a monophyletic clade of advanced sauropod dinosaurs within Eusauropoda, positioned as the sister group to basal eusauropods such as Jobaria tiguidensis. This placement stems from cladistic analyses that distinguish Neosauropoda from earlier-diverging eusauropods based on shared derived traits like hyposphene-hypantrum articulations in presacral vertebrae and a deep lateral pneumatic foramen on the cervical centra.[49] The clade was originally proposed by Bonaparte in 1986 but redefined by Wilson and Sereno in 1998 as the node-based group uniting Diplodocoidea and Macronaria, thereby expanding its scope to encompass Titanosauriformes within Macronaria and emphasizing its role as a crownward branch of sauropod evolution.[49] Internally, Neosauropoda exhibits a basal dichotomy between the two major subclades, Diplodocoidea (encompassing peg-toothed sauropods like Diplodocus) and Macronaria (including broad-nostriled forms like Camarasaurus and titanosaurs). This topology is consistently recovered in parsimony and model-based analyses, with Diplodocoidea characterized by elongate cervicals and a downturned mandibular symphysis, while Macronaria features a boxy skull and robust limb elements. Recent Bayesian phylogenetic analyses, incorporating stratigraphic and morphological data from over 150 taxa, affirm this split with strong nodal support, including posterior probabilities exceeding 0.95 for the Neosauropoda crown and its primary branches. A simplified cladogram of Neosauropoda, derived from integrated Bayesian tip-dating frameworks, illustrates these relationships:Neosauropoda

├── [Diplodocoidea](/page/Diplodocoidea) (PP > 0.95)

│ ├── Rebbachisauridae

│ ├── [Diplodocidae](/page/Diplodocidae)

│ └── Dicraeosauridae

└── [Macronaria](/page/Macronaria) (PP > 0.95)

├── Basal macronarians (e.g., [Camarasaurus](/page/Camarasaurus))

└── Titanosauriformes (PP > 0.98)

├── [Brachiosauridae](/page/Brachiosauridae)

└── Somphospondyli

Neosauropoda

├── [Diplodocoidea](/page/Diplodocoidea) (PP > 0.95)

│ ├── Rebbachisauridae

│ ├── [Diplodocidae](/page/Diplodocidae)

│ └── Dicraeosauridae

└── [Macronaria](/page/Macronaria) (PP > 0.95)

├── Basal macronarians (e.g., [Camarasaurus](/page/Camarasaurus))

└── Titanosauriformes (PP > 0.98)

├── [Brachiosauridae](/page/Brachiosauridae)

└── Somphospondyli