Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sauropoda

View on Wikipedia

| Sauropods Temporal range:

Early Jurassic – Late Cretaceous (Sinemurian – Maastrichtian, (probable Late Triassic record) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Six sauropods (top left to bottom right): Patagotitan, Barosaurus, Giraffatitan, Omeisaurus, Shunosaurus, and Amargasaurus | |||||

| Scientific classification | |||||

| Kingdom: | Animalia | ||||

| Phylum: | Chordata | ||||

| Class: | Reptilia | ||||

| Clade: | Dinosauria | ||||

| Clade: | Saurischia | ||||

| Clade: | †Sauropodomorpha | ||||

| Clade: | †Sauropodiformes | ||||

| Clade: | †Sauropoda Marsh, 1878 | ||||

| Subgroups | |||||

| |||||

| Synonyms | |||||

| |||||

Sauropoda (/sɔːˈrɒpədə/), whose members are called sauropods (/ˈsɔːrəpɒdz/;[1][2] from sauro- + -pod; lit. 'lizard-footed'), is a clade of saurischian ('lizard-hipped') dinosaurs. Sauropods had very long necks, long tails, small heads (relative to the rest of their body), and four thick, pillar-like legs. They are notable for the enormous sizes attained by some species, and the group includes the largest animals to have ever lived on land. Well-known genera include Alamosaurus, Apatosaurus, Argentinosaurus, Brachiosaurus, Brontosaurus, Camarasaurus, Diplodocus, Dreadnoughtus, and Mamenchisaurus.[3][4]

The oldest known unequivocal sauropod dinosaurs are known from the Early Jurassic.[5] Isanosaurus and Antetonitrus were originally described as Triassic sauropods,[6][7] but their age, and in the case of Antetonitrus also its sauropod status, were subsequently questioned.[8][5][9] Sauropod-like sauropodomorph tracks from the Fleming Fjord Formation (Greenland) might, however, indicate the occurrence of the group in the Late Triassic.[5] By the Late Jurassic (150 million years ago), sauropods had become widespread (especially the diplodocids and brachiosaurids). By the Late Cretaceous, one group of sauropods, the titanosaurs, had replaced all others and had a near-global distribution. However, as with all other non-avian dinosaurs alive at the time, the titanosaurs died out in the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. Fossilised remains of sauropods have been found on every continent, including Antarctica.[10][11][12][13]

The name Sauropoda was coined by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1878, and is derived from Ancient Greek, meaning "lizard foot".[14] Sauropods are one of the most recognizable groups of dinosaurs, and have become a fixture in popular culture due to their enormousness.

Complete sauropod fossil finds are extremely rare. Many species, especially the largest, are known only from isolated and disarticulated bones. Many near-complete specimens lack heads, tail tips and limbs.

Description

[edit]Sauropods were herbivorous (plant-eating), usually quite long-necked[15] quadrupeds (four-legged), often with spatulate (spatula-shaped: broad at the tip, narrow at the neck) teeth. They had relatively tiny heads, massive bodies, and most had long tails. Their hind legs were thick, straight, and powerful, ending in club-like feet with five toes, though only the inner three (or in some cases four) bore claws. Their forelimbs were rather more slender and typically ended in pillar-like hands built for supporting weight; often only the thumb bore a claw. Many illustrations of sauropods in the flesh miss these facts, inaccurately depicting sauropods with hooves capping the claw-less digits of the feet, or more than three claws or hooves on the hands. The proximal caudal vertebrae are extremely diagnostic for sauropods.[16]

Size

[edit]

The sauropods' most defining characteristic was their size. Even the dwarf sauropods (perhaps 5 to 6 metres (16 to 20 ft) long) were counted among the largest animals in their ecosystem. Their only real competitors in terms of size are the rorquals, such as the blue whale. But, unlike whales, sauropods were primarily terrestrial animals.

Their body structure did not vary as much as other dinosaurs, perhaps due to size constraints, but they displayed ample variety. Some, like the diplodocids, possessed tremendously long tails, which they may have been able to crack like a whip as a signal or to deter or injure predators,[17] or to make sonic booms.[18][19] Supersaurus, at 33 to 34 metres (108 to 112 ft) long,[20] was the longest sauropod known from reasonably complete remains, but others, like the old record holder, Diplodocus, were also extremely long. The holotype (and now lost) vertebra of Amphicoelias fragillimus (now Maraapunisaurus) may have come from an animal 58 metres (190 ft) long;[21] its vertebral column would have been substantially longer than that of the blue whale. However, research published in 2015 speculated that the size estimates of A. fragillimus may have been highly exaggerated.[22] The longest dinosaur known from reasonable fossils material is probably Argentinosaurus huinculensis with length estimates of 35 to 36 metres (115 to 118 ft) according to the most recent researches.[23][24] However the giant Barosaurus specimen BYU 9024 might have been even larger reaching lengths of 45–48 meters (148–157 ft).[23][24][25] Others, like the brachiosaurids, were extremely tall, with high shoulders and extremely long necks. The tallest sauropod was the giant Barosaurus specimen at 22 m (72 ft) tall.[23] By comparison, the giraffe, the tallest of all living land animals, is only 4.8 to 5.6 metres (16 to 18 ft) tall.

The best evidence indicates that the most massive were Argentinosaurus (65 to 80 metric tons (72 to 88 short tons)[26][23][24]), Mamenchisaurus sinocanadorum (60 to 80 metric tons or 66 to 88 short tons[24]), the giant Barosaurus specimen (60-80+ metric tons[23][24][25]) and Patagotitan with Puertasaurus (50 to 55 metric tons (49 to 54 long tons; 55 to 61 short tons)[23][24]). Meanwhile, 'mega-sauropods' such as Bruhathkayosaurus has long been scrutinized due to controversial debates on its validity, but recent photos re-surfacing in 2022 have legitimized it,[27] allowing for more updated estimates that range between 110 to 170 metric tons (120 to 190 short tons), rivaling the blue whale in size.[28] The weight of Amphicoelias fragillimus was estimated at 122.4 metric tons (120.5 long tons; 134.9 short tons) tons with lengths of up to nearly 60 meters (200 ft)[21] but 2015 research argued that these estimates were based on a diplodocid rather than the more modern rebbachisaurid, suggesting a much shorter length of 35–40 meters (115–130 ft) with mass between 80 and 120 metric tons (79 and 118 long tons; 88 and 132 short tons).[22] Additional finds indicate a number of species likely reached or exceeded weights of 40 tons.[29] The largest land animal alive today, the bush elephant, weighs no more than 10.4 metric tons (11.5 short tons).[30]

Among the smallest sauropods were the primitive Ohmdenosaurus (4 metres or 13 feet long), the dwarf titanosaur Magyarosaurus (6 metres or 20 feet long), and the dwarf brachiosaurid Europasaurus, which was 6.2 meters (20 ft) long as a fully-grown adult.[31] Its small stature was probably the result of insular dwarfism occurring in a population of sauropods isolated on an island of the late Jurassic in what is now the Langenberg area of northern Germany.[32][33] The diplodocoid sauropod Brachytrachelopan was the shortest member of its group because of its unusually short neck. Unlike other sauropods, whose necks could grow to up to four times the length of their backs, the neck of Brachytrachelopan was shorter than its backbone.

Fossils from perhaps the largest dinosaur ever found (MOZ-Pv 1221) were discovered in 2021 in the Neuquén Province of northwest Patagonia, Argentina. It is believed that they are from a titanosaur, which were amongst the largest sauropods.[34][29]

On or shortly before 29 March 2017 a sauropod footprint about 1.7 meters (5.6 feet) long was found at Walmadany in the Kimberley Region of Western Australia.[35] The report said that it was the biggest known yet. In 2020 Molina-Perez and Larramendi estimated the size of the animal at 31 meters (102 feet) and 72 tonnes (79.4 short tons) based on the 1.75-meter (5.7-foot) long footprint.[23]

Limbs and feet

[edit]As massive quadrupeds, sauropods developed specialized "graviportal" (weight-bearing) limbs. The hind feet were broad, and retained three claws in most species.[36] Particularly unusual compared with other animals were the highly modified front feet (manus). The front feet of sauropods were very dissimilar from those of modern large quadrupeds, such as elephants. Rather than splaying out to the sides to create a wide foot as in elephants, the manus bones of sauropods were arranged in fully vertical columns, with extremely reduced finger bones (though it is not clear if the most primitive sauropods, such as Vulcanodon and Barapasaurus, had such forefeet).[37] The front feet were so modified in eusauropods that individual digits would not have been visible in life.

The arrangement of the forefoot bone (metacarpal) columns in eusauropods was semi-circular, so sauropod forefoot prints are horseshoe-shaped. Unlike elephants, print evidence shows that sauropods lacked any fleshy padding to back the front feet, making them concave.[37] The only claw visible in most sauropods was the distinctive thumb claw (associated with digit I). Almost all sauropods had such a claw, though what purpose it served is unknown. The claw was largest (as well as tall and laterally flattened) in diplodocids, and very small in brachiosaurids, some of which seem to have lost the claw entirely based on trackway evidence.[38] Titanosaurs may have lost the thumb claw completely (with the exception of early forms, such as Janenschia).

Titanosaurs were most unusual among sauropods, as, across their history as a clade, they lost not just the external claw but also completely lost the digits of the front foot. Advanced titanosaurs had no digits or digit bones, and walked only on horseshoe-shaped "stumps" made up of the columnar metacarpal bones.[39]

Print evidence from Portugal shows that, in at least some sauropods (probably brachiosaurids), the bottom and sides of the forefoot column was likely covered in small, spiny scales, which left score marks in the prints.[40] In titanosaurs, the ends of the metacarpal bones that contacted the ground were unusually broad and squared-off, and some specimens preserve the remains of soft tissue covering this area, suggesting that the front feet were rimmed with some kind of padding in these species.[39]

Matthew Bonnan[41][42] has shown that sauropod dinosaur long bones grew isometrically: that is, there was little to no change in shape as juvenile sauropods became gigantic adults. Bonnan suggested that this odd scaling pattern (most vertebrates show significant shape changes in long bones associated with increasing weight support) might be related to a stilt-walker principle (suggested by amateur scientist Jim Schmidt) in which the long legs of adult sauropods allowed them to easily cover great distances without changing their overall mechanics.

Air sacs

[edit]Along with other saurischian dinosaurs (such as theropods, including birds), sauropods had a system of air sacs, evidenced by indentations and hollow cavities in most of their vertebrae that had been invaded by them. Pneumatic, hollow bones are a characteristic feature of all sauropods.[43] These air spaces reduced the overall weight of the massive necks that the sauropods had, and the air-sac system in general, allowing for a single-direction airflow through stiff lungs, made it possible for the sauropods to get enough oxygen.[44] This adaptation would have advantaged sauropods particularly in the relatively low oxygen conditions of the Jurassic and Early Cretaceous.[45]

The bird-like hollowing of sauropod bones was recognized early in the study of these animals, and, in fact, at least one sauropod specimen found in the 19th century (Ornithopsis) was originally misidentified as a pterosaur (a flying reptile) because of this.[46]

Armor

[edit]

Some sauropods had armor. There were genera with small clubs on their tails, a prominent example being Shunosaurus, and several titanosaurs, such as Saltasaurus and Ampelosaurus, had small bony osteoderms covering portions of their bodies.

Teeth

[edit]A study by Michael D'Emic and his colleagues from Stony Brook University found that sauropods evolved high tooth replacement rates to keep up with their large appetites. The study suggested that Nigersaurus, for example, replaced each tooth every 14 days, Camarasaurus replaced each tooth every 62 days, and Diplodocus replaced each tooth once every 35 days.[47] The scientists found qualities of the tooth affected how long it took for a new tooth to grow. Camarasaurus's teeth took longer to grow than those for Diplodocus because they were larger.[48]

It was also noted by D'Emic and his team that the differences between the teeth of the sauropods also indicated a difference in diet. Diplodocus ate plants low to the ground and Camarasaurus browsed leaves from top and middle branches. According to the scientists, the specializing of their diets helped the different herbivorous dinosaurs to coexist.[47][48]

Necks

[edit]Sauropod necks have been found at over 15 metres (49 ft) in length, a full six times longer than the world record giraffe neck.[44] Enabling this were a number of essential physiological features. The dinosaurs' overall large body size and quadrupedal stance provided a stable base to support the neck, and the head was evolved to be very small and light, losing the ability to orally process food. By reducing their heads to simple harvesting tools that got the plants into the body, the sauropods needed less power to lift their heads, and thus were able to develop necks with less dense muscle and connective tissue. This drastically reduced the overall mass of the neck, enabling further elongation.

Sauropods also had a great number of adaptations in their skeletal structure. Some sauropods had as many as 19 cervical vertebrae, whereas almost all mammals are limited to only seven. Additionally, each vertebra was extremely long and had a number of empty spaces in them which would have been filled only with air. An air-sac system connected to the spaces not only lightened the long necks, but effectively increased the airflow through the trachea, helping the creatures to breathe in enough air. By evolving vertebrae consisting of 60% air, the sauropods were able to minimize the amount of dense, heavy bone without sacrificing the ability to take sufficiently large breaths to fuel the entire body with oxygen.[44] According to Kent Stevens, computer-modeled reconstructions of the skeletons made from the vertebrae indicate that sauropod necks were capable of sweeping out large feeding areas without needing to move their bodies, but were unable to be retracted to a position much above the shoulders for exploring the area or reaching higher.[49]

Another proposed function of the sauropods' long necks was essentially a radiator to deal with the extreme amount of heat produced from their large body mass. Considering that the metabolism would have been doing an immense amount of work, it would certainly have generated a large amount of heat as well, and elimination of this excess heat would have been essential for survival.[50] It has also been proposed that the long necks would have cooled the veins and arteries going to the brain, avoiding excessively heated blood from reaching the head. It was in fact found that the increase in metabolic rate resulting from the sauropods' necks was slightly more than compensated for by the extra surface area from which heat could dissipate.[51]

Palaeobiology

[edit]Ecology

[edit]Dental microwear texture analysis (DMTA) performed on a titanosauriform sauropod from the Turonian-aged Tamagawa Formation suggests that the sauropod fed on plant material that was softer than insect exoskeletons or mollusc shells, with the diet likely consisting of ferns and gymnosperms. The DMTA results also suggested that sauropods likely masticated more energetically than present-day lepidosaurs do.[52]

When sauropods were first discovered, their immense size led many scientists to compare them with modern-day whales. Most studies in the 19th and early 20th centuries concluded that sauropods were too large to have supported their weight on land, and therefore that they must have been mainly aquatic. Most life restorations of sauropods in art through the first three quarters of the 20th century depicted them fully or partially immersed in water.[53] This early notion was cast in doubt beginning in the 1950s, when a study by Kermack (1951) demonstrated that, if the animal were submerged in several metres of water, the pressure would be enough to fatally collapse the lungs and airway.[54] However, this and other early studies of sauropod ecology were flawed in that they ignored a substantial body of evidence that the bodies of sauropods were heavily permeated with air sacs. In 1878, paleontologist E.D. Cope had even referred to these structures as "floats".

Beginning in the 1970s, the effects of sauropod air sacs on their supposed aquatic lifestyle began to be explored. Paleontologists such as Coombs and Bakker used this, as well as evidence from sedimentology and biomechanics, to show that sauropods were primarily terrestrial animals. In 2004, D.M. Henderson noted that, due to their extensive system of air sacs, sauropods would have been buoyant and would not have been able to submerge their torsos completely below the surface of the water; in other words, they would float, and would not have been in danger of lung collapse due to water pressure when swimming.[53]

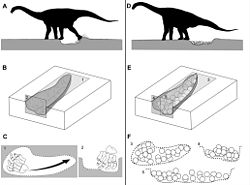

Evidence for swimming in sauropods comes from fossil trackways that have occasionally been found to preserve only the forefeet (manus) impressions. Henderson showed that such trackways can be explained by sauropods with long forelimbs (such as macronarians) floating in relatively shallow water deep enough to keep the shorter hind legs free of the bottom, and using the front limbs to punt forward.[53] However, due to their body proportions, floating sauropods would also have been very unstable and maladapted for extended periods in the water. This mode of aquatic locomotion, combined with its instability, led Henderson to refer to sauropods in water as "tipsy punters".[53]

While sauropods could therefore not have been aquatic as historically depicted, there is evidence that they preferred wet and coastal habitats. Sauropod footprints are commonly found following coastlines or crossing floodplains, and sauropod fossils are often found in wet environments or intermingled with fossils of marine organisms.[53] A good example of this would be the massive Jurassic sauropod trackways found in lagoon deposits on Scotland's Isle of Skye.[55] Studies published in 2021 suggest sauropods could not inhabit polar regions. This study suggests they were largely confined to tropical areas and had metabolisms that were very different to those of other dinosaurs, perhaps intermediate between mammals and reptiles.[56] New studies published by Taia Wyenberg-henzler in 2022 suggest that sauropods in North America declined due to undetermined reasons in regards to their niches and distribution during the end of the Jurassic and into the latest Cretaceous. Why this is remains unclear, but some similarities in feeding niches between iguanodontians, hadrosauroids, and sauropods have been suggested and may have resulted in some competition. However, this cannot fully explain the full decline in distribution of sauropods, as competitive exclusion would have resulted in a much more rapid decline than what is shown in the fossil record. Moreover, it must be determined as to whether sauropod declines in North America was the result of a change in preferred flora that sauropods ate, climate, or other factors. It is also suggested in this same study that iguanodontians and hadrosauroids took advantage of recently vacated niches left by a decline in sauropod diversity during the late Jurassic and the Cretaceous in North America.[57]

Herding and parental care

[edit]

Many lines of fossil evidence, from both bone beds and trackways, indicate that sauropods were gregarious animals that formed herds. However, the makeup of the herds varied between species. Some bone beds, for example a site from the Middle Jurassic of Argentina, appear to show herds made up of individuals of various age groups, mixing juveniles and adults. However, a number of other fossil sites and trackways indicate that many sauropod species travelled in herds segregated by age, with juveniles forming herds separate from adults. Such segregated herding strategies have been found in species such as Alamosaurus, Bellusaurus and some diplodocids.[58]

In a review of the evidence for various herd types, Myers and Fiorillo attempted to explain why sauropods appear to have often formed segregated herds. Studies of microscopic tooth wear show that juvenile sauropods had diets that differed from their adult counterparts, so herding together would not have been as productive as herding separately, where individual herd members could forage in a coordinated way. The vast size difference between juveniles and adults may also have played a part in the different feeding and herding strategies.[58]

Since the segregation of juveniles and adults must have taken place soon after hatching, and combined with the fact that sauropod hatchlings were most likely precocial, Myers and Fiorillo concluded that species with age-segregated herds would not have exhibited much parental care.[58] On the other hand, scientists who have studied age-mixed sauropod herds suggested that these species may have cared for their young for an extended period before reaching adulthood.[59] A 2014 study suggested that the time from laying the egg to the time of the hatching was likely to have been between 65 and 82 days.[60] Exactly how segregated versus age-mixed herding varied across different groups of sauropods is unknown. Further examples of gregarious behavior will need to be discovered from more sauropod species to detect possible distribution patterns.[58]

Multiple nesting sites discovered in Argentina and India contain 30-400 clutches of fossilized eggs that were found preserved, providing evidence of sauropod maternal care. Researchers suggest that sauropods might have settled in nesting grounds close to volcanic activity for geothermal incubation, in which the mothers keep their eggs warm. This behavior is similar to modern birds and reptiles who follow the same method.[61][62][63]

Rearing stance

[edit]

Since early in the history of their study, scientists, such as Osborn, have speculated that sauropods could rear up on their hind legs, using the tail as the third 'leg' of a tripod.[64] A skeletal mount depicting the diplodocid Barosaurus lentus rearing up on its hind legs at the American Museum of Natural History is one illustration of this hypothesis. In a 2005 paper, Rothschild and Molnar reasoned that if sauropods had adopted a bipedal posture at times, there would be evidence of stress fractures in the forelimb 'hands'. However, none were found after they examined a large number of sauropod skeletons.[65]

Heinrich Mallison (in 2009) was the first to study the physical potential for various sauropods to rear into a tripodal stance. Mallison found that some characters previously linked to rearing adaptations were actually unrelated (such as the wide-set hip bones of titanosaurs) or would have hindered rearing. For example, titanosaurs had an unusually flexible backbone, which would have decreased stability in a tripodal posture and would have put more strain on the muscles. Likewise, it is unlikely that brachiosaurids could rear up onto the hind legs, as their center of gravity was much farther forward than other sauropods, which would cause such a stance to be unstable.[66]

Diplodocids, on the other hand, appear to have been well adapted for rearing up into a tripodal stance. Diplodocids had a center of mass directly over the hips, giving them greater balance on two legs. Diplodocids also had the most mobile necks of sauropods, a well-muscled pelvic girdle, and tail vertebrae with a specialised shape that would allow the tail to bear weight at the point it touched the ground. Mallison concluded that diplodocids were better adapted to rearing than elephants, which do so occasionally in the wild. He also argues that stress fractures in the wild do not occur from everyday behaviour,[66] such as feeding-related activities (contra Rothschild and Molnar).[65]

Head and neck posture

[edit]

There is little agreement over how sauropods held their heads and necks, and the postures they could achieve in life.

Whether sauropods' long necks could be used for browsing high trees has been questioned based on calculations suggesting that just pumping blood up to the head in such a posture[67] for long would have used some half of its energy intake.[68] Further, to move blood to such a height—dismissing posited auxiliary hearts in the neck[69]—would require a heart 15 times as large as of a similar-sized whale.[70]

The above have been used to argue that the long neck must instead have been held more or less horizontally, presumed to enable feeding on plants over a wide area with less need to move about, yielding a large energy saving for such a large animal. Reconstructions of the necks of Diplodocus and Apatosaurus have therefore often portrayed them in near-horizontal, so-called "neutral, undeflected posture".[71]

However, research on living animals demonstrates that almost all extant tetrapods hold the base of their necks sharply flexed when alert, showing that any inference from bones about habitual "neutral postures"[71] is deeply unreliable.[72][73] Meanwhile, computer modeling of ostrich necks has raised doubts over the flexibility needed for stationary grazing.[74][75][76]

Trackways and locomotion

[edit]

Sauropod trackways and other fossil footprints (known as "ichnites") are known from abundant evidence present on most continents. Ichnites have helped support other biological hypotheses about sauropods, including general fore and hind foot anatomy (see Limbs and feet above). Generally, prints from the forefeet are much smaller than the hind feet, and often crescent-shaped. Occasionally ichnites preserve traces of the claws, and help confirm which sauropod groups lost claws or even digits on their forefeet.[77]

Sauropod tracks from the Villar del Arzobispo Formation of early Berriasian age in Spain support the gregarious behaviour of the group. The tracks are possibly more similar to Sauropodichnus giganteus than any other ichnogenera, although they have been suggested to be from a basal titanosauriform. The tracks are wide-gauge, and the grouping as close to Sauropodichnus is also supported by the manus-to-pes distance, the morphology of the manus being kidney bean-shaped, and the morphology of the pes being subtriangular. It cannot be identified whether the footprints of the herd were caused by juveniles or adults, because of the lack of previous trackway individual age identification.[78]

Generally, sauropod trackways are divided into three categories based on the distance between opposite limbs: narrow gauge, medium gauge, and wide gauge. The gauge of the trackway can help determine how wide-set the limbs of various sauropods were and how this may have impacted the way they walked.[77] A 2004 study by Day and colleagues found that a general pattern could be found among groups of advanced sauropods, with each sauropod family being characterised by certain trackway gauges. They found that most sauropods other than titanosaurs had narrow-gauge limbs, with strong impressions of the large thumb claw on the forefeet. Medium gauge trackways with claw impressions on the forefeet probably belong to brachiosaurids and other primitive titanosauriformes, which were evolving wider-set limbs but retained their claws. Primitive true titanosaurs also retained their forefoot claw but had evolved fully wide gauge limbs. Wide gauge limbs were retained by advanced titanosaurs, trackways from which show a wide gauge and lack of any claws or digits on the forefeet.[79]

Occasionally, only trackways from the forefeet are found. Falkingham et al.[80] used computer modelling to show that this could be due to the properties of the substrate. These need to be just right to preserve tracks.[81] Differences in hind limb and fore limb surface area, and therefore contact pressure with the substrate, may sometimes lead to only the forefeet trackways being preserved.

Biomechanics and speed

[edit]

In a study published in PLoS ONE on October 30, 2013, by Bill Sellers, Rodolfo Coria, Lee Margetts et al., Argentinosaurus was digitally reconstructed to test its locomotion for the first time. Before the study, the most common way of estimating speed was through studying bone histology and ichnology. Commonly, studies about sauropod bone histology and speed focus on the postcranial skeleton, which holds many unique features, such as an enlarged process on the ulna, a wide lobe on the ilia, an inward-slanting top third of the femur, and an extremely ovoid femur shaft. Those features are useful when attempting to explain trackway patterns of graviportal animals. When studying ichnology to calculate sauropod speed, there are a few problems, such as only providing estimates for certain gaits because of preservation bias, and being subject to many more accuracy problems.[82]

To estimate the gait and speed of Argentinosaurus, the study performed a musculoskeletal analysis. The only previous musculoskeletal analyses were conducted on hominoids, terror birds, and other dinosaurs. Before they could conduct the analysis, the team had to create a digital skeleton of the animal in question, show where there would be muscle layering, locate the muscles and joints, and finally find the muscle properties before finding the gait and speed. The results of the biomechanics study revealed that Argentinosaurus was mechanically competent at a top speed of 2 m/s (5 mph) given the great weight of the animal and the strain that its joints were capable of bearing.[83] The results further revealed that much larger terrestrial vertebrates might be possible, but would require significant body remodeling and possible sufficient behavioral change to prevent joint collapse.[82]

Body size

[edit]

Sauropods were gigantic descendants of surprisingly small ancestors. Basal dinosauriformes, such as Pseudolagosuchus and Marasuchus from the Middle Triassic of Argentina, weighed approximately 1 kg (2.2 lb) or less. These evolved into saurischia, which saw a rapid increase of bauplan size, although more primitive members like Eoraptor, Panphagia, Pantydraco, Saturnalia and Guaibasaurus still retained a moderate size, possibly under 10 kg (22 lb). Even with these small, primitive forms, there is a notable size increase among sauropodomorphs, although scanty remains of this period make interpretation conjectural. There is one definite example of a small derived sauropodomorph: Anchisaurus, under 50 kg (110 lb), even though it is closer to the sauropods than Plateosaurus and Riojasaurus, which were upwards of 1 t (0.98 long tons; 1.1 short tons) in weight.[50]

Evolving from sauropodomorphs, the sauropods were huge. Their giant size probably resulted from an increased growth rate made possible by tachymetabolic endothermy, a trait which evolved in sauropodomorphs. Once branched into sauropods, sauropodomorphs continued steadily to grow larger, with smaller sauropods, like the Early Jurassic Barapasaurus and Kotasaurus, evolving into even larger forms like the Middle Jurassic Mamenchisaurus and Patagosaurus. Responding to the growth of sauropods, their theropod predators grew also, as shown by an Allosaurus-sized coelophysoid from Germany.[50]

Size in Neosauropoda

[edit]Neosauropoda is quite plausibly the clade of dinosaurs with the largest body sizes ever to have existed. The few exceptions of smaller size are hypothesized to be caused by island dwarfism, or other ecological pressures, although there is a trend in some Titanosauria towards a smaller size. The titanosaurs, however, were some of the largest sauropods ever. Other than titanosaurs, diplodocoids also reached truly gigantic sizes. Meanwhile, a clade of diplodocoids, called Dicraeosauridae, are identified by a small to medium[clarification needed] body size. No sauropods were very small, however, for even "dwarf" sauropods are larger than 500 kg (1,100 lb), a size reached by only about 10% of all mammalian species.[50]

Independent gigantism

[edit]Although in general, sauropods were large, a gigantic size (40 t (39 long tons; 44 short tons) or more) was reached independently at multiple times in their evolution. Many gigantic forms existed in the Late Jurassic (specifically Kimmeridgian), such as the turiasaur Turiasaurus, the mamenchisaurids Mamenchisaurus and Xinjiangtitan, the diplodocoids Diplodocus, Apatosaurus, Supersaurus and Barosaurus, the camarasaurid Camarasaurus, and the brachiosaurids Brachiosaurus and Giraffatitan. Through the Early to Late Cretaceous, the giants Sauroposeidon, Paralititan, Argentinosaurus, Puertasaurus, Antarctosaurus, Dreadnoughtus, Notocolossus, Futalognkosaurus, Patagotitan and Alamosaurus lived, with all possibly being titanosaurs. One sparsely known possible giant is Huanghetitan ruyangensis, only known from 3 m (9.8 ft) long ribs. These giant species lived in the Late Jurassic to the Late Cretaceous, appearing independently over a time span of 85 million years.[50]

Dwarfism in sauropods

[edit]Two well-known island dwarf species of sauropods are the Cretaceous Magyarosaurus (at one point its identity as a dwarf was challenged) and the Jurassic Europasaurus, both from Europe. Even though these sauropods are small, the only way to prove they are true dwarfs is through a study of their bone histology. A study by Martin Sander and colleagues in 2006 examined eleven individuals of Europasaurus holgeri using bone histology and demonstrated that the small island species evolved through a decrease in the growth rate of long bones as compared to rates of growth in ancestral species on the mainland.[84] Two other possible dwarfs are Rapetosaurus, which existed on the island of Madagascar, an isolated island in the Cretaceous, and Ampelosaurus, a titanosaur that lived on the Iberian peninsula of southern Spain and France. Amanzia from Switzerland might also be a dwarf, but this has yet to be proven.[50] One of the most extreme cases of island dwarfism is found in Europasaurus, a relative of the much larger Camarasaurus and Brachiosaurus: it was only about 6.2 m (20 ft) long, an identifying trait of the species. As for all dwarf species, their reduced growth rate led to their small size.[31][50] Another taxon of tiny sauropods, the saltasaurid titanosaur Ibirania, 5.7 metres (19 feet) long, lived a non-insular context in Upper Cretaceous Brazil, and is an example of nanism resultant from other ecological pressures.[85]

Paleopathology and paleoparasitology

[edit]Sauropods are rarely known for preserved injuries or signs of illnesses, but more recent discoveries show they could suffer from such pathologies. A diplodocid specimen from the Morrison Formation referred to as "Dolly" was described in 2022 with evidence of a severe respiratory infection.[86][87] Sauropod ribs from Yunyang County, Chongqing, in southwest China show evidence of rib breakage by way of traumatic fracture, bone infection, and osteosclerosis.[88] A sauropod tibia exhibiting initial fracture has been described from the Middle Jurassic of Yunyang County in southwestern China.[89]

Ibirania, a nanoid titanosaur fossil from Brazil, suggests that individuals of various genera were susceptible to diseases such as osteomyelitis and parasite infestations. The specimen hails from the late cretaceous São José do Rio Preto Formation, Bauru Basin, and was described in the journal Cretaceous Research by Aureliano et al. (2021).[90] Examination of the titanosaur's bones revealed what appear to be parasitic blood worms similar to the prehistoric Paleoleishmania but are 10-100 times larger, that seemed to have caused the osteomyelitis. The fossil is the first known instance of an aggressive case of osteomyelitis being caused by blood worms in an extinct animal.[91][92][93]

History of discovery

[edit]The first scraps of fossil remains now recognized as sauropods all came from England and were originally interpreted in a variety of different ways. Their relationship to other dinosaurs was not recognized until well after their initial discovery.

The first sauropod fossil to be scientifically described was a single tooth known by the non-Linnaean descriptor Rutellum implicatum.[94] This fossil was described by Edward Lhuyd in 1699, but was not recognized as a giant prehistoric reptile at the time.[95] Dinosaurs would not be recognized as a group until over a century later.

Richard Owen published the first modern scientific descriptions of sauropods in 1841, in a book and a paper naming Cardiodon and Cetiosaurus. Cardiodon was known only from two unusual, heart-shaped teeth (from which it got its name), which could not be identified beyond the fact that they came from a previously unknown large reptile. Cetiosaurus was known from slightly better, but still scrappy remains. Owen thought at the time that Cetiosaurus was a giant marine reptile related to modern crocodiles, hence its name, which means "whale lizard". A year later, when Owen coined the name Dinosauria, he did not include Cetiosaurus and Cardiodon in that group.[96]

In 1850, Gideon Mantell recognized the dinosaurian nature of several bones assigned to Cetiosaurus by Owen. Mantell noticed that the leg bones contained a medullary cavity, a characteristic of land animals. He assigned these specimens to the new genus Pelorosaurus, and grouped it together with the dinosaurs. However, Mantell still did not recognize the relationship to Cetiosaurus.[46]

The next sauropod find to be described and misidentified as something other than a dinosaur were a set of hip vertebrae described by Harry Seeley in 1870. Seeley found that the vertebrae were very lightly constructed for their size and contained openings for air sacs (pneumatization). Such air sacs were at the time known only in birds and pterosaurs, and Seeley considered the vertebrae to come from a pterosaur. He named the new genus Ornithopsis, or "bird face" because of this.[46]

When more complete specimens of Cetiosaurus were described by Phillips in 1871, he finally recognized the animal as a dinosaur related to Pelorosaurus.[97] However, it was not until the description of new, nearly complete sauropod skeletons from the United States (representing Apatosaurus and Camarasaurus) later that year that a complete picture of sauropods emerged. An approximate reconstruction of a complete sauropod skeleton was produced by artist John A. Ryder, hired by paleontologist E.D. Cope, based on the remains of Camarasaurus, though many features were still inaccurate or incomplete according to later finds and biomechanical studies.[98] Also in 1877, Richard Lydekker named another relative of Cetiosaurus, Titanosaurus, based on an isolated vertebra.[46]

In 1878, the most complete sauropod yet was found and described by Othniel Charles Marsh, who named it Diplodocus. With this find, Marsh also created a new group to contain Diplodocus, Cetiosaurus, and their increasing roster of relatives to differentiate them from the other major groups of dinosaurs. Marsh named this group Sauropoda, or "lizard feet".[46]

Classification

[edit]The first phylogenetic definition of Sauropoda was published in 1997 by Salgado and colleagues. They defined the clade as a node-based taxon, containing "the most recent common ancestor of Vulcanodon karibaensis and Eusauropoda and all of its descendants".[99] Later, several stem-based definitions were proposed, including one by Yates (2007), who defined Sauropoda as "the most inclusive clade that includes Saltasaurus loricatus but not Melanorosaurus readi".[100][101]

Proponents of this definition also use the clade name Gravisauria, defined as the most recent ancestor of Tazoudasaurus naimi and Saltasaurus loricatus and all of its descendants[102] for the clade equivalent to Sauropoda as defined by Salgado et al.[103] The clade Gravisauria was appointed by the French paleontologist Ronan Allain and Moroccan paleontologist Najat Aquesbi in 2008 when a cladistic analysis of the dinosaur found by Allain, Tazoudasaurus, as the outcome was that the family Vulcanodontidae. The group includes Tazoudasaurus and Vulcanodon, and the sister taxon Eusauropoda, but also certain species such as Antetonitrus, Gongxianosaurus and Isanosaurus that do not belong in Vulcanodontidae but to an even more basic position occupied in Sauropoda. It made sense to have Sauropoda compared to this, more derived group that included Vulcanodontidae and Eusauropoda in a definition: defined as the group formed by the last common ancestor of Tazoudasaurus and Saltasaurus (Bonaparte and Powell, 1980) and all its descendants. Aquesbi mentioned two synapomorphies, shared derived characteristics of Gravisauria: the vertebrae are wider side to side than front to rear and possession of asymmetrical condyles femoris at the bottom of the femur. Those were previously not thought to be Eusauropoda synapomorphies but Allian found these properties also on Tazoudasaurus.[104]

Gravisauria split off in the Early Jurassic, around the Pliensbachian and Toarcian, 183 million years ago, and Aquesbi thought that this was part of a much larger revolution in the fauna, which includes the disappearance of Prosauropoda, Coelophysoidea and basal Thyreophora, which they attributed to a worldwide mass extinction.[104]

The phylogenetic relationships of the sauropods have largely stabilised in recent years, though there are still some uncertainties, such as the placement of Euhelopus, Haplocanthosaurus, Jobaria and Nemegtosauridae.

Cladogram after an analysis presented by Sander and colleagues in 2011.[50]

| †Sauropoda | |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "sauropod". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. OCLC 1032680871.

- ^ "sauropod". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ Tschopp, E.; Mateus, O.; Benson, R. B. J. (2015). "A specimen-level phylogenetic analysis and taxonomic revision of Diplodocidae (Dinosauria, Sauropoda)". PeerJ. 3 e857. doi:10.7717/peerj.857. PMC 4393826. PMID 25870766.

- ^ blogs.scientificamerican.com tetrapod-zoology 2015-04-24 That Brontosaurus Thing

- ^ a b c Jens N. Lallensack; Hendrik Klein; Jesper Milàn; et al. (2017). "Sauropodomorph dinosaur trackways from the Fleming Fjord Formation of East Greenland: Evidence for Late Triassic sauropods". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 62 (4): 833–843. doi:10.4202/app.00374.2017. hdl:10362/33146.

- ^ Eric Buffetaut; Varavudh Suteethorn; Gilles Cuny; et al. (2000). "The earliest known sauropod dinosaur". Nature. 407 (6800): 72–74. Bibcode:2000Natur.407...72B. doi:10.1038/35024060. PMID 10993074. S2CID 4387776.

- ^ Adam M. Yates; James W. Kitching (2003). "The earliest known sauropod dinosaur and the first steps towards sauropod locomotion". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 270 (1525): 1753–1758. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2417. PMC 1691423. PMID 12965005.

- ^ Blair W. McPhee; Adam M. Yates; Jonah N. Choiniere; Fernando Abdala (2014). "The complete anatomy and phylogenetic relationships of Antetonitrus ingenipes (Sauropodiformes, Dinosauria): implications for the origins of Sauropoda". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 171 (1): 151–205. doi:10.1111/zoj.12127. S2CID 82631097.

- ^ Blair W. Mcphee; Emese M. Bordy; Lara Sciscio; Jonah N. Choiniere (2017). "The sauropodomorph biostratigraphy of the Elliot Formation of southern Africa: Tracking the evolution of Sauropodomorpha across the Triassic–Jurassic boundary". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 62 (3): 441–465. Bibcode:2017AcPaP..62.2017M. doi:10.4202/app.00377.2017.

- ^ Fernando E. Novas (2009). The Age of Dinosaurs in South America. Indiana University Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-253-35289-7.

- ^ Oklahoma Geology Notes. Oklahoma Geological Survey. 2003. p. 40.

- ^ Beau Riffenburgh (2007). Encyclopedia of the Antarctic. Taylor & Francis. p. 415. ISBN 978-0-415-97024-2.

- ^ J. J. Alistair Crame; Geological Society of London (1989). Origins and Evolution of the Antarctic Biota. Geological Society. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-903317-44-3.

- ^ Marsh, O.C. (1878). "Principal characters of American Jurassic dinosaurs. Part I"". American Journal of Science and Arts. 16 (95): 411–416. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-16.95.411. hdl:2027/hvd.32044107172876. S2CID 219245525.

- ^ Michael P. Taylor; Mathew J. Wedel (2013). "Why sauropods had long necks; and why giraffes have short necks". PeerJ. 1 e36. doi:10.7717/peerj.36. PMC 3628838. PMID 23638372.

The necks of the sauropod dinosaurs were by far the longest of any animal...

- ^ Tidwell, V., Carpenter, K. & Meyer, S. 2001. New Titanosauriform (Sauropoda) from the Poison Strip Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation (Lower Cretaceous), Utah. In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. D. H. Tanke & K. Carpenter (eds.). Indiana University Press, Eds. D.H. Tanke & K. Carpenter. Indiana University Press. 139-165.

- ^ Bakker, Robert (1994). "The Bite of the Bronto". Earth. 3 (6): 26–33.

- ^ Peterson, Ivars (March 2000). "Whips and Dinosaur Tails". Science News. Archived from the original on 2007-07-14. Retrieved 2007-07-07.

- ^ Myhrvold, Nathan P.; Currie, Philip John (1997). "Supersonic sauropods? Tail dynamics in the diplodocids" (PDF). Paleobiology. 23 (4): 393–409. Bibcode:1997Pbio...23..393M. doi:10.1017/S0094837300019801. ISSN 0094-8373. S2CID 83696153.

- ^ Lovelace, David M.; Hartman, Scott A.; Wahl, William R. (2007). "Morphology of a specimen of Supersaurus (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Morrison Formation of Wyoming, and a re-evaluation of diplodocid phylogeny". Arquivos do Museu Nacional. 65 (4): 527–544.

- ^ a b Carpenter, K. (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 36: 131–138. S2CID 56215581.

- ^ a b Cary Woodruff & John R Foster (July 15, 2015). "The fragile legacy of Amphicoelias fragillimus (Dinosauria: Sauropoda; Morrison Formation - Latest Jurassic)" (PDF). PeerJ PrePrints. 3 e1037. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 31, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Molina-Perez & Larramendi (2020). Dinosaur Facts and Figures: The Sauropods and Other Sauropodomorphs. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 42–267. Bibcode:2020dffs.book.....M.

- ^ a b c d e f Paul, Gregory S. (2019). "Determining the largest known land animal: A critical comparison of differing methods for restoring the volume and mass of extinct animals" (PDF). Annals of the Carnegie Museum. 85 (4): 335–358. Bibcode:2019AnCM...85..335P. doi:10.2992/007.085.0403. S2CID 210840060.

- ^ a b Taylor, Mike (2019). "Supersaurus, Ultrasaurus and Dystylosaurus in 2019, part 2b: the size of the BYU 9024 animal".

- ^ Mazzetta, G.V.; Christiansen, P.; Fariña, R.A. (2004). "Giants and Bizarres: Body Size of Some Southern South American Cretaceous Dinosaurs" (PDF). Historical Biology. 16 (2–4): 71–83. Bibcode:2004HBio...16...71M. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.694.1650. doi:10.1080/08912960410001715132. S2CID 56028251. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Pal, Saurabh; Ayyasami, Krishnan (27 June 2022). "The lost titan of Cauvery". Geology Today. 38 (3): 112–116. Bibcode:2022GeolT..38..112P. doi:10.1111/gto.12390. ISSN 0266-6979. S2CID 250056201.

- ^ Paul, Gregory S.; Larramendi, Asier (11 April 2023). "Body mass estimate of Bruhathkayosaurus and other fragmentary sauropod remains suggest the largest land animals were about as big as the greatest whales". Lethaia. 56 (2): 1–11. Bibcode:2023Letha..56..2.5P. doi:10.18261/let.56.2.5. ISSN 0024-1164. S2CID 259782734.

- ^ a b Otero, Alejandro; Carballido, José L.; Salgado, Leonardo; Canudo, José Ignacio; Garrido, Alberto C. (12 January 2021). "Report of a giant titanosaur sauropod from the Upper Cretaceous of Neuquén Province, Argentina". Cretaceous Research. 122 104754. Bibcode:2021CrRes.12204754O. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104754. S2CID 233582290.

- ^ Larramendi, A. (2015). "Shoulder height, body mass and shape of proboscideans" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 60. doi:10.4202/app.00136.2014. S2CID 2092950. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-04-11.

- ^ a b Martin Sander, P.; Mateus, Octávio; Laven, Thomas; Knötschke, Nils (2006). "Bone histology indicates insular dwarfism in a new Late Jurassic sauropod dinosaur". Nature. 441 (7094): 739–41. Bibcode:2006Natur.441..739M. doi:10.1038/nature04633. PMID 16760975. S2CID 4361820.

- ^ Nicole Klein (2011). Biology of the Sauropod Dinosaurs: Understanding the Life of Giants. Indiana University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-253-35508-9.

- ^ Reitner, Joachim; Yang, Qun; Wang, Yongdong; Reich, Mike (6 September 2013). Palaeobiology and Geobiology of Fossil Lagerstätten through Earth History: A Joint Conference of the "Paläontologische Gesellschaft" and the "Palaeontological Society of China", Göttingen, Germany, September 23-27, 2013. Universitätsverlag Göttingen. p. 21. ISBN 978-3-86395-135-1.

- ^ Baker, Harry (2021). "Massive new dinosaur might be the largest creature to ever roam Earth". LiveScience.com. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ Palazzo, Chiara (28 March 2017). "World's biggest dinosaur footprints found in 'Australia's Jurassic Park'". The Telegraph.

- ^ Bonnan, M.F. 2005. Pes anatomy in sauropod dinosaurs: implications for functional morphology, evolution, and phylogeny; pp. 346-380 in K. Carpenter and V. Tidwell (eds.), Thunder-Lizards: The Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- ^ a b Bonnan, Matthew F. (2003). "The evolution of manus shape in sauropod dinosaurs: Implications for functional morphology, forelimb orientation, and phylogeny" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 23 (3): 595–613. Bibcode:2003JVPal..23..595B. doi:10.1671/A1108. S2CID 85667519.

- ^ Upchurch, P. (1994). "Manus claw function in sauropod dinosaurs". Gaia. 10: 161–171.

- ^ a b Apesteguía, S. (2005). "Evolution of the titanosaur metacarpus". Pp. 321-345 in Tidwell, V. and Carpenter, K. (eds.) Thunder-Lizards: The Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

- ^ Milàn, J.; Christiansen, P.; Mateus, O. (2005). "A three-dimensionally preserved sauropod manus impression from the Upper Jurassic of Portugal: implications for sauropod manus shape and locomotor mechanics". Kaupia. 14: 47–52.

- ^ Bonnan, M. F. (2004). "Morphometric Analysis of Humerus and Femur Shape in Morrison Sauropods: Implications for Functional Morphology and Paleobiology" (PDF). Paleobiology. 30 (3): 444–470. Bibcode:2004Pbio...30..444B. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2004)030<0444:maohaf>2.0.co;2. JSTOR 4096900. S2CID 86258781.

- ^ Bonnan, Matthew F. (2007). "Linear and Geometric Morphometric Analysis of Long Bone Scaling Patterns in Jurassic Neosauropod Dinosaurs: Their Functional and Paleobiological Implications". The Anatomical Record. 290 (9): 1089–1111. doi:10.1002/ar.20578. PMID 17721981. S2CID 41222371.

- ^ Wedel, M.J. (2009). "Evidence for bird-like air sacs in Saurischian dinosaurs". (pdf) Journal of Experimental Zoology, 311A: 18pp.

- ^ a b c Taylor, M.P.; Wedel, M.J. (2013). "Why sauropods had long necks; and why giraffes have short necks". PeerJ. 1 e36. doi:10.7717/peerj.36. PMC 3628838. PMID 23638372.

- ^ Ward, Peter Douglas (2006). "The Jurassic: Dinosaur Hegemony in a Low-Oxygen World". Out of Thin Air: Dinosaurs, Birds, and Earth's Ancient Atmosphere. Washington, D. C.: Joseph Henry Press. pp. 199–222. ISBN 0-309-10061-5.

- ^ a b c d e Taylor, M.P. (2010). "Sauropod dinosaur research: a historical review". In Richard Moody, Eric Buffetaut, David M. Martill and Darren Naish (eds.), Dinosaurs (and other extinct saurians): a historical perspective. HTML abstract.

- ^ a b D'Emic, Michael D.; Whitlock, John A.; Smith, Kathlyn M.; Fisher, Daniel C.; Wilson, Jeffrey A. (17 July 2013). "Evolution of High Tooth Replacement Rates in Sauropod Dinosaurs". PLOS ONE. 8 (7) e69235. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...869235D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069235. PMC 3714237. PMID 23874921.

- ^ a b Barber, Elizabeth (2004-06-09). "No toothbrush required: Dinosaurs replaced their smile every month". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2013-08-14.

- ^ Stevens, K.A. (2013). "The Articulation of Sauropod Necks: Methodology and Mythology". PLOS ONE. 8 (10) e78572. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...878572S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078572. PMC 3812995. PMID 24205266.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sander, P. Martin; Christian, Andreas; Clauss, Marcus; Fechner, Regina; Gee, Carole T.; Griebeler, Eva-Maria; Gunga, Hanns-Christian; Hummel, Jürgen; Mallison, Heinrich; Perry, Steven F.; et al. (2011). "Biology of the sauropod dinosaurs: the evolution of gigantism". Biological Reviews. 86 (1): 117–155. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00137.x. ISSN 1464-7931. PMC 3045712. PMID 21251189.

- ^ Henderson, D.M. (2013). "Sauropod Necks: Are They Really for Heat Loss?". PLOS ONE. 8 (10) e77108. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...877108H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0077108. PMC 3812985. PMID 24204747.

- ^ Sakaki, Homare; Winkler, Daniela E.; Kubo, Tai; Hirayama, Ren; Uno, Hikaru; Miyata, Shinya; Endo, Hideki; Sasaki, Kazuhisa; Takisawa, Toshio; Kubo, Mugino O. (August 2022). "Non-occlusal dental microwear texture analysis of a titanosauriform sauropod dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous (Turonian) Tamagawa Formation, northeastern Japan". Cretaceous Research. 136 105218. Bibcode:2022CrRes.13605218S. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2022.105218.

- ^ a b c d e Henderson, D.M. (2004). "Tipsy punters: sauropod dinosaur pneumaticity, buoyancy and aquatic habits". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 271 (Suppl 4): S180–S183. Bibcode:2004PBioS.271.0136H. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2003.0136. PMC 1810024. PMID 15252977.

- ^ Kermack, K.A. (1951). "A note on the habits of sauropods". Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. 4 (44): 830–832. doi:10.1080/00222935108654213.

- ^ "Giant wading sauropod discovery made on Isle of Skye (Wired UK)". Wired UK. 2015-12-02. Retrieved 2016-03-22.

- ^ "Sauropod dinosaurs were restricted to warmer regions of Earth".

- ^ Wyenberg-Henzler T. 2022. Ecomorphospace occupation of large herbivorous dinosaurs from Late Jurassic through to Late Cretaceous time in North America. PeerJ 10:e13174 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13174

- ^ a b c d Myers, T.S.; Fiorillo, A.R. (2009). "Evidence for gregarious behavior and age segregation in sauropod dinosaurs" (PDF). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 274 (1–2): 96–104. Bibcode:2009PPP...274...96M. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2009.01.002.

- ^ Coria, R.A. (1994). "On a monospecific assemblage of sauropod dinosaurs from Patagonia: implications for gregarious behavior". GAIA. 10: 209–213.

- ^ Ruxton, Graeme D.; Birchard, Geoffrey F.; Deeming, D. Charles (2014). "Incubation time as an important influence on egg production and distribution into clutches for sauropod dinosaurs". Paleobiology. 40 (3): 323–330. Bibcode:2014Pbio...40..323R. doi:10.1666/13028. S2CID 84437615.

- ^ A new Argentinean nesting site showing neosauropod dinosaur reproduction in a Cretaceous hydrothermal environment, Nature Communications, Volume: 1, Article number: 32, DOI: doi:10.1038/ncomms1031

- ^ H. Dhiman et al.. 2023. New Late Cretaceous titanosaur sauropod dinosaur egg clutches from lower Narmada Valley, India: Palaeobiology and taphonomy. PLoS ONE 18 (1): e0278242; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0278242

- ^ Tanaka, Kohei & Zelenitsky, Darla & Therrien, François & Kobayashi, Yoshitsugu. (2018). Nest substrate reflects incubation style in extant archosaurs with implications for dinosaur nesting habits. Scientific Reports. 8. 10.1038/s41598-018-21386-x.

- ^ Osborn, H. F. (1899). "A Skeleton of Diplodocus, Recently Mounted in the American Museum". Science. 10 (259): 870–4. Bibcode:1899Sci....10..870F. doi:10.1126/science.10.259.870. PMID 17788971.

- ^ a b Rothschild, B.M. & Molnar, R.E. (2005). "Sauropod Stress Fractures as Clues to Activity". In Carpenter, K. & Tidswell, V. (eds.). Thunder Lizards: The Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 381–391. ISBN 978-0-253-34542-4.

- ^ a b Mallison, H. (2009). "Rearing for food? Kinetic/dynamic modeling of bipedal/tripodal poses in sauropod dinosaurs". P. 63 in Godefroit, P. and Lambert, O. (eds), Tribute to Charles Darwin and Bernissart Iguanodons: New Perspectives on Vertebrate Evolution and Early Cretaceous Ecosystems. Brussels.

- ^ Bujor, Mara (2009-05-29). "Did sauropods walk with their necks upright?". ZME Science.

- ^ Seymour, RS (June 2009). "Raising the sauropod neck: it costs more to get less". Biol. Lett. 5 (3): 317–9. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0096. PMC 2679936. PMID 19364714.

- ^ Choy, DS; Altman, P (1992-08-29). "The cardiovascular system of barosaurus: an educated guess". Lancet. 340 (8818): 534–6. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(92)91722-k. PMID 1354287. S2CID 7378155.

- ^ Seymour, RS; Lillywhite, HB (September 2000). "Hearts, neck posture and metabolic intensity of sauropod dinosaurs". Proc. Biol. Sci. 267 (1455): 1883–7. Bibcode:2000PBioS.267.1883S. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1225. PMC 1690760. PMID 11052540.

- ^ a b Stevens, K.A.; Parrish, J.M. (1999). "Neck posture and feeding habits of two Jurassic sauropod dinosaurs". Science. 284 (5415): 798–800. Bibcode:1999Sci...284..798S. doi:10.1126/science.284.5415.798. PMID 10221910.

- ^ Taylor, M.P., Wedel, M.J., and Naish, D. (2009). "Head and neck posture in sauropod dinosaurs inferred from extant animals". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 54 (2), 2009: 213-220 abstract

- ^ Museums and TV have dinosaurs' posture all wrong, claim scientists. Guardian, 27 May 2009

- ^ Cobley MJ; Rayfield EJ; Barrett PM (14 August 2013). "Inter-Vertebral Flexibility of the Ostrich Neck: Implications for Estimating Sauropod Neck Flexibility". PLOS ONE. 8 (8) e72187. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...872187C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0072187. PMC 3743800. PMID 23967284.

- ^ n.d (2013-08-14). "Ostrich Necks Reveal Sauropod Movements, Food Habits". Science Daily. Retrieved 2013-08-16.

- ^ Ghose, Tia (2013-08-15). "Ouch! Long-necked dinosaurs may actually have had stiff necks". NBC News Live Science. Retrieved 2013-08-16.

- ^ a b Riga, B.J.G.; Calvo, J.O. (2009). "A new wide-gauge sauropod track site from the Late Cretaceous of Mendoza, Neuquen Basin, Argentina" (PDF). Palaeontology. 52 (3): 631–640. Bibcode:2009Palgy..52..631G. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2009.00869.x.

- ^ Castanera, D.; Barco, J. L.; Díaz-Martínez, I.; Gascón, J. S. H.; Pérez-Lorente, F. L.; Canudo, J. I. (2011). "New evidence of a herd of titanosauriform sauropods from the lower Berriasian of the Iberian range (Spain)". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 310 (3–4): 227–237. Bibcode:2011PPP...310..227C. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2011.07.015.

- ^ Day, J.J.; Norman, D.B.; Gale, A.S.; Upchurch, P.; Powell, H.P. (2004). "A Middle Jurassic dinosaur trackway site from Oxfordshire, UK". Palaeontology. 47 (2): 319–348. Bibcode:2004Palgy..47..319D. doi:10.1111/j.0031-0239.2004.00366.x.

- ^ Falkingham, P. L.; Bates, K. T.; Margetts, L.; Manning, P. L. (2011-02-23). "Simulating sauropod manus-only trackway formation using finite-element analysis". Biology Letters. 7 (1): 142–145. Bibcode:2011BiLet...7..142F. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2010.0403. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 3030862. PMID 20591856.

- ^ Falkingham, P. L.; Bates, K. T.; Margetts, L.; Manning, P. L. (2011-08-07). "The 'Goldilocks' effect: preservation bias in vertebrate track assemblages". Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 8 (61): 1142–1154. Bibcode:2011JRSI....8.1142F. doi:10.1098/rsif.2010.0634. ISSN 1742-5689. PMC 3119880. PMID 21233145.

- ^ a b Sellers, W. I.; Margetts, L.; Coria, R. A. B.; Manning, P. L. (2013). Carrier, David (ed.). "March of the Titans: The Locomotor Capabilities of Sauropod Dinosaurs". PLOS ONE. 8 (10) e78733. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...878733S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078733. PMC 3864407. PMID 24348896.

- ^ Szabo, John (2011). Dinosaurs. University of Akron: McGraw Hill. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-121-09332-4.

- ^ Brian K. Hall; Benedikt Hallgrímsson (1 June 2011). Strickberger's Evolution. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 446. ISBN 978-1-4496-4722-3.

- ^ Navarro, Bruno A.; Ghilardi, Aline M.; Aureliano, Tito; Díaz, Verónica Díez; Bandeira, Kamila L. N.; Cattaruzzi, André G. S.; Iori, Fabiano V.; Martine, Ariel M.; Carvalho, Alberto B.; Anelli, Luiz E.; Fernandes, Marcelo A.; Zaher, Hussam (2022-09-15). "A New Nanoid Titanosaur (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Brazil". Ameghiniana. 59 (5): 477. Bibcode:2022Amegh..59..477N. doi:10.5710/AMGH.25.08.2022.3477. ISSN 0002-7014. S2CID 251875979.

- ^ "Achoo! Respiratory illness gave young 'Dolly' the dinosaur flu-like symptoms". Live Science. 10 February 2022.

- ^ "Discovery of what ailed Dolly the dinosaur is a first, researchers say". CNN. 10 February 2022.

- ^ Tan, Chao; Yu, Hai-Dong; Ren, Xin-Xin; Dai, Hui; Ma, Qing-Yu; Xiong, Can; Zhao, Zhi-Qiang; You, Hai-Lu (2022). "Pathological ribs in sauropod dinosaurs from the Middle Jurassic of Yunyang, Chongqing, Southwestern China". Historical Biology. 35 (4): 475–482. doi:10.1080/08912963.2022.2045979. S2CID 247172509.

- ^ Tan, Chao; Wang, Ping; Xiong, Can; Wei, Zhao-Ying; Tu, Yan; Ma, Qing-Yu; Ren, Xin-Xin; You, Hai-Lu (17 September 2024). "A sauropod tibia with initial fracture from the Middle Jurassic in Yunyang, Chongqing, southwest China". Historical Biology. 37 (9): 2131–2138. doi:10.1080/08912963.2024.2403598. ISSN 0891-2963. Retrieved 27 September 2024 – via Taylor and Francis Online.

- ^ Aureliano, Tito; Nascimento, Carolina S. I.; Fernandes, Marcelo A.; Ricardi-Branco, Fresia; Ghilardi, Aline M. (2021-02-01). "Blood parasites and acute osteomyelitis in a non-avian dinosaur (Sauropoda, Titanosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous Adamantina Formation, Bauru Basin, Southeast Brazil". Cretaceous Research. 118 104672. Bibcode:2021CrRes.11804672A. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104672. ISSN 0195-6671. S2CID 225134198.

- ^ Aureliano, Tito; Nascimento, Carolina S.I.; Fernandes, Marcelo A.; Ricardi-Branco, Fresia; Ghilardi, Aline M. (February 2021). "Blood parasites and acute osteomyelitis in a non-avian dinosaur (Sauropoda, Titanosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous Adamantina Formation, Bauru Basin, Southeast Brazil". Cretaceous Research. 118 104672. Bibcode:2021CrRes.11804672A. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104672. S2CID 225134198.

- ^ Baraniuk, Chris (January 2021). "Gruesome 'Blood Worms' Invaded a Dinosaur's Leg Bone, Fossil Suggests". Scientific American.

- ^ "Cretaceous Titanosaur Suffered from Blood Parasites and Severe Bone Inflammation | Paleontology | Sci-News.com". Breaking Science News | Sci-News.com.

- ^ Delair, J.B.; Sarjeant, W.A.S. (2002). "The earliest discoveries of dinosaurs: the records re-examined". Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 113 (3): 185–197. Bibcode:2002PrGA..113..185D. doi:10.1016/S0016-7878(02)80022-0.

- ^ Lhuyd, E. (1699). Lithophylacii Britannici Ichnographia, sive lapidium aliorumque fossilium Britannicorum singulari figura insignium. Gleditsch and Weidmann: London.

- ^ Owen, R. (1842). "Report on British Fossil Reptiles". Part II. Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, Plymouth, England.

- ^ Phillips, J. (1871). Geology of Oxford and the Valley of the Thames. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 523 pp.

- ^ Osborn, H. F.; Mook, C. C. (1919-01-01). "Camarasaurus, Amphicoelias, and other sauropods of Cope". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 30 (1): 379–388. Bibcode:1919GSAB...30..379O. doi:10.1130/GSAB-30-379. ISSN 0016-7606.

- ^ Salgado, L.; Coria, R. A.; Calvo, J. O. (1997). "Evolution of titanosaurid sauropods. 1: Phylogenetic analysis based on the postcranial evidence". Ameghiniana. 34 (1): 3–32. ISSN 1851-8044.

- ^ Peyre de Fabrègues, C.; Allain, R.; Barriel, V. (2015). "Root causes of phylogenetic incongruence observed within basal sauropodomorph interrelationships: Sauropodomorph Interrelationships". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 175 (3): 569–586. doi:10.1111/zoj.12290. S2CID 83180197.

- ^ Yates, A. M. (2007). "Solving a dinosaurian puzzle: the identity of Aliwalia rex Galton". Historical Biology. 19 (1): 93–123. Bibcode:2007HBio...19...93Y. doi:10.1080/08912960600866953. S2CID 85202575.

- ^ Allain, R.; Aquesbi, N. (2008). "Anatomy and phylogenetic relationships of Tazoudasaurus naimi (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the late Early Jurassic of Morocco". Geodiversitas. 30 (2): 345–424.

- ^ Pol, D.; Otero, A.; Apaldetti, C.; Martínez, R. N. (2021). "Triassic sauropodomorph dinosaurs from South America: The origin and diversification of dinosaur dominated herbivorous faunas". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 107 103145. Bibcode:2021JSAES.10703145P. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2020.103145. S2CID 233579282.

- ^ a b Allain, R. and Aquesbi, N. (2008). "Anatomy and phylogenetic relationships of Tazoudasaurus naimi (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the late Early Jurassic of Morocco." Geodiversitas, 30(2): 345-424.

External links

[edit] Media related to Sauropoda at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sauropoda at Wikimedia Commons- Strauss, Bob (2008). "Sauropods: The biggest dinosaurs that ever lived". about.com. Types of dinosaurs. Archived from the original on 2017-02-02. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- Rogers, K.C.; Wilson, J.A. (2005). The Sauropods: Evolution and Paleobiology. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24623-3.

- Upchurch, P.; Barrett, P.M.; Dodson, P. (2004). "Sauropoda". In Weishampel, D.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 259–322.

Sauropoda

View on GrokipediaDescription

Size and proportions

Sauropods exhibited remarkable gigantism, with body lengths typically ranging from 10 to 30 meters in most species, though maximum estimates reach up to 35–40 meters in titanosaurs such as Argentinosaurus huinculensis and Patagotitan mayorum. Shoulder heights varied from 3–5 meters in basal forms to 6–7 meters at the hips in larger derived taxa, allowing these quadrupeds to tower over contemporary herbivores. Such dimensions underscore their status as the largest terrestrial animals, far surpassing modern elephants in scale.[6][7] Mass estimates for sauropods are derived primarily from volumetric modeling of skeletal reconstructions and scaling equations based on limb bone circumferences, which account for the animals' overall body proportions. A widely used method involves the equation , where is body mass in kilograms and is the combined midshaft circumference (in meters) of the humerus and femur; this approach, calibrated on extant vertebrates and applied to dinosaurs, provides robust predictions for quadrupedal forms like sauropods. For instance, Dreadnoughtus schrani yielded an initial mass estimate of 59 metric tons using this limb-scaling technique on its near-complete skeleton, though subsequent volumetric reassessments suggested a lower value around 30–40 tons to avoid implausibly high tissue densities. Similarly, Patagotitan mayorum was estimated at 69 tons (±17 tons) via femoral and humeral scaling, with volumetric models ranging from 45 to 77 tons depending on soft-tissue assumptions. Argentinosaurus huinculensis, known from fragmentary remains, reached approximately 73 tons based on multivariate regressions incorporating vertebral cross-sections and fibular length.[8][9][10][7][6] Proportional differences among sauropods reflect evolutionary trends toward extreme elongation in specific regions, contributing to their overall size. Basal sauropods, such as Vulcanodon karibaensis, possessed more compact bodies with relatively shorter necks (comprising about 20–30% of total length) and tails, resembling transitional forms from bipedal ancestors. In contrast, derived diplodocids like Diplodocus longus featured disproportionately elongated tails that could account for over 50% of body length (up to 14 meters alone), paired with moderately long necks for a whip-like counterbalance. Macronarian lineages, including titanosaurs, emphasized neck elongation, with some reaching 15 meters, while maintaining robust trunks and shorter tails relative to diplodocoids. These scaling patterns, quantified through three-dimensional phylogenetic models, highlight how regional allometry enabled gigantism without uniform body expansion.[11]Neck and head

Sauropod necks exhibit remarkable elongation, primarily achieved through an increased number of cervical vertebrae compared to other dinosaurs. Basal sauropodomorphs typically possessed around 12 cervical vertebrae, but this count increased iteratively in sauropod lineages, reaching 13–18 in most eusauropods and up to 19 in advanced forms such as Mamenchisaurus hochuanensis.[12] For instance, Diplodocus has 15 cervicals, a configuration considered standard for diplodocoids.[13] This elongation was enabled by modifications to vertebral morphology, including the proportional lengthening of centra and neural arches, as well as extensive pneumaticity that invaded the bone tissue. Pneumatic diverticula from cervical air sacs hollowed out the vertebrae, substantially reducing their density and mass—sometimes by over 50% in mid-cervical elements—while maintaining structural integrity under gravitational loads.[14] This lightweighting was crucial for supporting necks that could exceed 14 meters in length without compromising locomotion or stability.[5] Sauropod skulls were disproportionately small relative to body size, typically accounting for about 1/200th of total body mass and less than 3% of overall length in large species.[15] For example, the skull of an adult Diplodocus, from a 30-meter-long animal, measured under 1 meter.[16] Morphologically, skulls varied by clade: diplodocids featured narrow, elongate snouts with a prominent subnarial fenestra and laterally compressed rostra adapted for precise cropping, while titanosaurs often displayed more boxy, robust crania with shorter, broader snouts and reduced fenestration.[17] Some titanosaurs, like Nemegtosaurus, converged on diplodocid-like elongation, highlighting plasticity in cranial form.[18] The head incorporated sensory adaptations centered on the enlarged, dorsally positioned external nares, which occupied up to 25% of the skull's dorsal surface in some taxa. These nares likely supported expanded olfactory epithelium for enhanced scent detection, with the anterior placement of fleshy nostrils maximizing exposure to odor plumes.[19] Comparative studies suggest a possible nasal valve function, where soft tissues within the narial passage directed airflow efficiently for both olfaction and respiration, akin to mechanisms in modern vertebrates.[2] Debates on neck flexibility emphasize structural constraints from zygapophyseal articulations, which interlocked pre- and postzygapophyses to limit lateral bending and twisting, promoting a primarily sagittal range of motion. Finite element analysis of cervical vertebrae confirms this, revealing high stiffness in lateral directions to prevent buckling under the neck's mass, with maximum deflections estimated at 10–20 degrees per joint in the horizontal plane.[20] Such adaptations supported a near-horizontal resting posture, with flexibility concentrated in the anterior neck for foraging.[21]Limbs and posture

Sauropod limbs were adapted as graviportal structures, featuring robust, columnar bones that supported immense body masses through a fully upright posture, with the long axis of each limb oriented vertically beneath the body to minimize bending moments and optimize load distribution. The humerus, radius, ulna, femur, tibia, and fibula exhibited thick cortical bone and straight shafts, facilitating weight transmission directly from the girdles to the ground without significant lateral deviation.[22] Forelimb and hindlimb proportions varied significantly across sauropod clades, reflecting adaptations to different body plans and potential feeding strategies. In diplodocids such as Diplodocus, forelimbs were markedly shorter than hindlimbs, with forelimb/hindlimb length ratios typically below 0.60, resulting in a more horizontal trunk orientation. Conversely, brachiosaurids like Brachiosaurus displayed pillar-like forelimbs with ratios of 0.66 or greater, where humeri were elongated and nearly equal in length to femora, elevating the anterior body and supporting a more inclined posture. These ratios underscore the mechanical efficiency of sauropod quadrupedalism, as evidenced by the semi-tubular arrangement of metacarpals and metatarsals that enhanced forelimb stability under load.[21] Sauropod feet featured specialized anatomy for weight-bearing, with the manus and pes forming compact, pillar-like units. The manus typically comprised five metacarpals arranged in a semi-circular arcade, held nearly vertical to distribute pressure evenly across digits I–V, though only the pollex (digit I) bore a prominent claw, while the structure functioned as a rigid block for support rather than grasping.[22] In the pes, three weight-bearing claws were present on digits I–III, with columnar metapodials and broad, padded soles inferred from trackway impressions, enabling stable ground contact for massive bodies.[23] For instance, articulated manus and pes remains of Camarasaurus reveal a phalangeal formula of 2-2-1-1-1 (manus) and 2-3-4-2-0 (pes), with robust phalanges reinforcing the foot's role in load transmission.[23] Pelvic and vertebral adaptations further reinforced the upright stance, with the sacrum incorporating high neural spines and a wedge-shaped morphology to align the vertebral column vertically over the limb girdles. The fused sacral vertebrae, often numbering five, featured elevated neural spines that anchored powerful epaxial muscles, stabilizing the pelvis against shear forces during locomotion.[24] This configuration, combined with robust ilia and ischia flaring outward to accommodate massive gluteal musculature, ensured efficient weight transfer to the hindlimbs.[21] Articulated skeletons provide direct evidence of these adaptations, particularly in load-bearing scaling of the forelimbs. In Apatosaurus, well-preserved specimens such as those from the Carnegie Museum exhibit proportionally robust humeri and radii, with cross-sectional areas scaling positively with body size to withstand compressive loads exceeding 20 tons, as confirmed by three-dimensional moment arm analyses of neosauropod forelimbs.[25] These structures demonstrate how forelimb geometry minimized stress concentrations, supporting the pillar-erect posture essential for sauropod terrestrial life.[26]Respiratory system

Sauropod dinosaurs possessed a bird-like respiratory system characterized by an extensive network of air sacs, evidenced by pneumatic foramina and internal chambers in their vertebrae. These foramina, which served as entry points for air sac diverticula, are particularly prominent in the cervical and dorsal vertebrae, indicating the presence of cervical air sacs that extended into the neck region. In taxa such as Apatosaurus, pneumatization is extensive, with fossae and foramina visible on the centra and neural arches of most presacral vertebrae, supporting the invasion of diverticula from both cervical and abdominal air sacs. Abdominal air sacs are inferred from pneumatic features in the posterior dorsal, sacral, and sometimes caudal vertebrae, forming a comprehensive system that permeated the axial skeleton.[27][28][29] This air sac system facilitated unidirectional airflow through the lungs, analogous to that in modern birds, where air passes continuously in one direction across gas-exchange surfaces during both inhalation and exhalation. In sauropods, the pulmonary apparatus likely included a series of air sacs—cervical, clavicular, cranial thoracic, caudal thoracic, and abdominal—that minimized dead space and maximized oxygen extraction efficiency. Quantitative assessments of vertebral pneumaticity suggest this system reduced skeletal mass by 30-40% or more relative to solid bone, alleviating structural demands in gigantic bodies while maintaining rigidity through interconnected bony laminae. Such mass reduction was crucial for supporting the metabolic costs of extreme body sizes.[27][30][31] The respiratory system's integration with sauropod neck elongation is evident in the extensive pneumatic diverticula that filled spaces within elongated cervical vertebrae, preventing collapse under gravitational stress and optimizing weight distribution. These cervical diverticula, branching from the air sacs, not only lightened the skeleton but also enhanced ventilatory efficiency by extending the respiratory tract. Comparatively, this avian-style physiology enabled higher oxygen delivery rates than in reptiles, supporting elevated metabolic rates necessary for the growth and maintenance of sauropod giants, potentially approaching endothermic levels during ontogeny.[32][30][27]Dentition and feeding apparatus