Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pixel art

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2025) |

Pixel art[note 1] is a form of digital art drawn with graphical software where images are built using pixels as the only building block.[2] It is widely associated with the low-resolution graphics from 8-bit and 16-bit era computers, arcade machines and video game consoles, in addition to other limited systems such as LED displays and graphing calculators, which have a limited number of pixels and colors available.[3] The art form is still employed to this day by pixel artists and game studios, even though the technological limitations have since been surpassed.[3][4]

Most works of pixel art are also restrictive both in file size and the number of colors used in their color palette for reasons such as software limitations, to achieve a certain aesthetic, or to reduce the perceived noise. Older forms of pixel art tend to employ smaller palettes, with some video games being made using just two colors (1-bit color depth). Because of these self-imposed limitations, pixel art presents strong similarities with many traditional restrictive art forms such as mosaics, cross-stitch, and fuse beads.[2]

There is no precise classification for pixel art, but an artwork is usually considered as such if deliberate thought was put into each individual pixel of the image. Standard digital artworks or low-resolution photographs are also composed of pixels, but they would only be considered pixel art if the individual pixels were placed with artistic intent, even if the pixels are clearly visible or prominent.

The phrases "dot art" and "pixel pushing" are sometimes used as synonyms for pixel art, particularly by Japanese artists. The term spriting sometimes refers to the activity of making pixel art elements for video games specifically. The concept most likely originated from the word sprite, which is used in computer graphics to describe a two-dimensional bitmap that can be used as a building block in the construction of larger scenes.

Definition

[edit]

Pixel art is commonly differentiated from other digital imagery when the pixels used play an important individual role in the composition of the artwork, usually requiring deliberate control over the placement of each individual pixel. When purposefully editing in this way, changing the position of a few pixels can have a large effect on the image.

A common characteristic in pixel art is the low overall color count in the image. Pixel art as a medium mimics a lot of traits found in older video game graphics, rendered by machines capable of only outputting a limited number of colors at once.

As images get higher in resolution, pixels get harder to distinguish from each other, and the importance of their careful placement is diminished. The exact point at which this occurs and the conditions change to where a piece cannot be reasonably called "pixel art" is subjective.

History

[edit]Origin

[edit]

Some traditional art forms, like counted-thread embroidery (including cross-stitch) and some kinds of mosaic and beadwork, are very similar to pixel art and could be considered as non-digital counterparts or predecessors.[2] These art forms construct pictures out of small colored units similar to the pixels of modern digital computing.

Some of the earliest examples of pixel art could be found in analog electronic advertising displays, such as the ones from New York City during the early 20th century, with simple monochromatic light bulb matrix displays extant circa 1937.[5] Pixel art as it is known today largely originates from the golden age of arcade video games, with games such as Space Invaders (1978) and Pac-Man (1980), and 8-bit consoles such as the Nintendo Entertainment System (1983) and Master System (1985).

The term pixel art was first published in a journal letter by Adele Goldberg and Robert Flegal of Xerox Palo Alto Research Center in 1982.[6] The practice, however, goes back at least 11 years before that, for example in Richard Shoup's SuperPaint system in 1972, also at Xerox PARC.[7]system 22345

1970s

[edit]Because of the severe restrictions of early graphics, the first instances of pixel art in video games were relatively abstract. The low resolution of computers and game consoles forced game designers to carefully design game assets by deliberate placement of individual pixels, to form recognizable symbols, characters, or items. Simple function-based avatars (or player-surrogates) such as spaceships, cars, or tanks required a minimum of animation and computing power, while enemies, terrain, and power-ups were often represented by symbols or simple designs.[8] Due to the limited hardware of the 1970s, abstraction, as in the case of Pong's relatively simple design, sometimes led to better game readability and commercial success than attempting more detailed representational art.

Although computers had been used to create art since the 1960s and microcomputers were used in the late 1970s[9] and there are examples of digital art utilizing a more pixelated aesthetic,[10] there is no well-known tradition of pixel art from the 1970s that differentiated between the deliberate placement of pixels or the aestheticization of individual pixels in contrast to other forms of digital painting or digital art. For this reason, one could argue that pixel art was not a recognized medium or artform in the 1970s.

1980s

[edit]

In what is sometimes referred to as the golden age of video games or golden age of arcade video games, the 1980s saw a period of innovation in video games, both as a new artform and a form of entertainment. During the early 1980s, video game creators were mainly programmers and not graphic designers. Technological innovation led to market pressure for more representational and "realistic" graphics in games.[8] As graphics improved, it became possible to replace hand-drawn game assets with imported pictures or 3D polygons, which contributed to pixel art developing as a separate art form.

Gradually, professional artists and graphic designers had a bigger impact in the video game industry. Sierra Entertainment released Mystery House, pixelled by Roberta Williams, and the King's Quest series; and Lucasfilm Games released games such as Maniac Mansion, Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders, and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Graphic Adventure. Mark J. Ferrari, an artist at Lucasfilm Games, later said:[11]

When I was first hired by Lucasfilm Games in 1987 to do artwork for their computer games, pixel graphics was not thought of by anyone as an 'art form'. The use of pixels was not an aesthetic choice – as it certainly is now. If anything, pixels were an unavoidable and very irksome obstacle to the creation of any 'real art' for use in the exciting but bewildering new realm of computer entertainment. There were no pixel artists then – at all! There were only traditional artists.

Nevertheless, the aesthetic of 1980s video games had a major impact on contemporary and future pixel art, both in video games, the demoscene graphics and among independent artists. As computers became more affordable in the 1980s, software such as DEGAS Elite (1986) for the Atari ST, Deluxe Paint (1985) and Deluxe Paint 2 (1986) for the Commodore Amiga, and Paint Magic for the Commodore 64, inspired many later pixel artists to create digital art by careful placement of pixels. In the case of the Commodore 64 and the Amstrad CPC, some early pixel artists used joysticks and keyboards to pixel.[12]

With the rise of the demoscene movement in Europe in the late 1980s, artists who were proficient with creating pixel art using 8-bit computers like the Commodore 64 and ZX Spectrum or 16-bit computers like the Atari ST began to publish their pixel art as demos. Demogroups would often include coders (programmers), musicians, and graphicians, where graphicians were a common name for graphic designers and/or pixel artists. Although some graphicians worked on adding art to cracked video games (cracktros), the demoscene contributed to artistic communities creating pixel art for its own sake as art. These were often shared via floppy disks that were handed from person to person or via the postal service.[13] The golden age of the demoscene and its associated pixel art milieu, however, is often regarded as beginning in the early 1990s.[12]

1990s

[edit]

Before the 1990s, display systems were mostly based on a small 4-bit palette of imposed colors (16 fixed shades innate to each system, often incompatible with one another). The coming decade greatly improved the graphics standard with the appearance of increased color depth and indexed color palettes (For example, 512 colors for the Atari ST and the Mega Drive, 4,096 for the Amiga ECS, 32,768 for the Super Nintendo, and 16,777,216 for the Amiga AGA and the VGA mode of the PCs). During the 1990s, 2D games with manually painted graphics saw increasing competition from 3-dimensional games and games using pre-rendered 3D assets.[14] Still, pixel art games like Flashback, The Secret of Monkey Island, The Chaos Engine, Street Fighter III: 3rd Strike, Super Mario World, and The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past had a major influence on future artists in the game industry, the contemporary demoscene and the aesthetic of pixel art in later decades.[11]

In addition to pixel art influenced by video games, pixel artists (or graphicians) in the demoscene continued to make pixel art for demos and cracktros. Some demoscene pixel artists active in the 1990s have cited movies and urban graffiti as important influences for their art, particularly in designing logos.[15][16] In addition to copying sprites from existing video games, demoscene pixel artists also copied the work of popular artists and illustrators such as Ian Miller and Simon Bisley.[17] Competition gradually became an increasingly important part of demoscene gatherings, including pixel art (graphics) competitions, and as teenagers and young adults were the major demographic in these gatherings, a lot of demoscene pixel art referenced familiar fantasy, science fiction and cyberpunk tropes. Demoscene competitions had a major effect in shaping the direction of pixel art. Prominent artists would look for ways to innovate, display superior technique, overcome technical restrictions, and in many cases aim for photorealism through anti-aliasing.[18]

As the internet became more available in the 1990s, pixel artists and demosceners gradually began to spread their pixel art via websites, instant messaging, and online file sharing. While the demoscene was arguably most popular among young men, an online movement began in the late 1990s known as pixel dolls or 'dollz', which was popular among young women. The increased popularity of online chatting and personal webpages at a time before digital cameras were common led to an increased demand for personal representation through personalized avatars. These avatars often took the form of pixel dolls, being pixel art characters that could be outfitted with different clothing and accessories. As pixel dolls grew more and more common, many pixel artists gradually began to develop this as an independent artform.

2000s

[edit]

The 2000s were a pivotal decade for pixel art establishing itself as an artform practiced around the world, separate from other forms of digital art. In particular, the Pixelation forum and Pixel Joint gallery are credited as the most influential English-speaking online communities, connecting pixel artists all over the world in a way that the mostly Western European demoscene movement had not.[19][20][14] Pixelation was a web forum where artists could share pixel art to give and receive feedback. Its main focus was critiquing, developing skills and understanding of pixel art, more so than simply sharing art for the sake of admiration, entertainment, or competition. Pixel Joint is an online gallery where members can submit personal work and comment on other members' pixel art. It has features such as weekly challenges, a forum, a hall of fame, and a monthly top 10-pixel art competition based on member voting.

Over time, the overlapping but separate communities of Pixelation and Pixel Joint were engaged in online discourse about the nature of pixel art, inspiring widely shared tutorials and arguably contributing to a new paradigm that was different from the pixel art of the 1990s.[21] A major concern was to establish pixel art as its own medium and/or art form, separate from other types of digital art, such as Oekaki. In particular, highly restricted palettes (e.g. a maximum of 8 or 16 colors) were argued by some to be a defining feature of pixel art. One example is the so-called "8 color gentlemen's club", consisting of pixel artists who celebrated pixel art with 8 colors.[22] The use of transparent layers and smudging tools was also considered non-pixel art and unacceptable for the Pixel Joint gallery. Whereas the demoscene had, to a large degree, revolved around physical gatherings and groups of artists, musicians, and programmers collaborating, pixel art communities on Pixel Joint and Pixelation were based mostly on online interaction among individual artists. On Pixel Joint, pixel art made through collaboration between artists was not accepted in the gallery but considered a separate pursuit. The relatively strict ideas of what constituted acceptable pixel art, enforced by moderators on Pixel Joint, led to repeated conflict but also contributed to pixel art standing out as a separate medium at a time when many types of digital paintings were shared on the internet, on websites like DeviantArt. In particular, several prominent artists mention Cure's tutorials as significant for learning about pixel art as a separate art medium or art form.[21]

After the golden age of demoscene pixel art in the 1990s, many notable pixel artists of that milieu took a break from pixel art in the 2000s - although some made an early transition to join Pixelation and Pixel Joint, such as Gas 13 and Tomic.[22] While activity did decline, the demoscene continued to explore pixel art on platforms from the late 1980s and early 1990s, particularly using the Commodore 64 and Atari computers.[23]

Pixel doll communities grew rapidly during the 2000s, in large part due to the continued growth of forums, message boards, and chat services. With websites like the Doll Palace, Eden Enchanted, DeviantArt, and many personal websites, pixel dolls were increasingly recognized as a new art form, with public feedback, competition, tutorials, best practices, and rules of conduct. The 2000s were arguably the height of pixel doll popularity, in part because of various online communities that made use of pixel dolls for avatars and the popularity of internet forums in an age before social media. Despite this, there was relatively little interaction between the pixel doll communities and other pixel art communities such as Pixel Joint, Pixelation, or the demoscene.

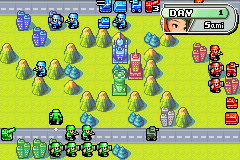

In video games for computers and consoles during the 2000s, pixel art was largely abandoned in favor of more modern graphics, particularly based on 3D. Many professional game artists who had been working with pixel art either left the industry or switched to other forms of digital art. This arguably contributed to pixel art establishing itself as an independent art form, practiced mostly by independent artists rather than game industry employees. There are a few notable exceptions, such as Habbo Hotel, which inspired a great amount of isometric pixel art, and Advance Wars, for Game Boy Advance.

2010s

[edit]

The popularity of pixel art accelerated during the 2010s.[24][25][14] One major contribution to this trend was the success of several 'retro' pixel art games such as Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP (2011), Terraria (2011), Fez (2012), Papers, Please (2013), Shovel Knight (2014), Undertale (2015), Owlboy (2016), Stardew Valley (2016), Deltarune (2018+), Celeste (2018), and Octopath Traveler (2018).[26] Many of these games combined low-resolution game assets with non-pixel art (NPA) elements such as filters, high definition UI, or special effects.[27][28] The increased attention on pixel art in media and the game industry coincided with the rapid growth of pixel art communities. Owlboy's art director, Simon Andersen, explained that he wanted to show the advantages of the pixel as an art medium, pushing the potential of the artistic technique and showcase pixel art done properly, without millions of colors or 3D captures.[29] In contrast, the heavily stylized and abstract Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP made extensive use of filters and non-pixel art graphics. Superbrothers: Sword and Sworcery also allowed players to share various in-game achievements on Twitter, the #sworcery hashtag went viral, contributing to the renewed interest in pixel art in video games.[30]

Pixel Joint and Pixelation remained important communities with a growing number of contributors, but the 2010s saw the rise of new communities on Reddit, DeviantArt, Instagram, and Twitter. While Pixelation, in particular, had a core of very dedicated, often professional, pixel artists and Pixel Joint had moderators who accepted or rejected submissions to its online gallery, new pixel art communities in social media were naturally less cohesive, yet more open. Not only did social media contribute significantly to the continued growth of pixel art, and more traffic to older pixel art websites, but websites like Tumblr, Twitter, and Instagram also gave significant global attention to new pixel artists outside of the traditional pixel art communities, such as Waneella and Pixel Jeff.[31][32]

During the 2010s, the demoscene arguably entered a silver age, as several older artists returned to their hobbies after a hiatus.[33][34] In addition, the increasing popularity of pixel art in this decade also attracted new artists to the demoscene, who had not been active during the 1990s and 2000s.[35] It is important to note that the demoscene and its graphics competitions never stopped, but the 2010s could nevertheless be considered a period of rejuvenation.

As advanced digital painting software like Photoshop became more widely available and easier to use, the pixel doll community split into a group of artists using traditional pixel art, known as pixel-shaders, and a group of artists using more advanced tools, known as tool-shaders. As internet forums lost popularity and drawn avatars were increasingly replaced by photos in internet communities, the pixel dolling community gradually became less active in this decade.

Perhaps because of the rise of pixel art in video games and social media, pixel art was also seen in other areas of popular culture and even made its way to public museums. Ivan Dixon and Paul Robertson received international attention for making a pixel art version of The Simpsons' introduction sequence.[36] Eboy became well known for their isometric pixel art displays, often used for advertisement or sold as independent art.[37][38][14] The work of pixel artists such as Octavi Navarro and Gustavo Viselner was featured in major newspapers and magazines.[39][40] French urban artist Invader received international attention for his urban pixel art mosaics, seen around the world.[41] Among 1980s-inspired synthwave artists and groups, pixel art was used to make music videos, such as Valenberg's work for Perturbator and a Gunship music video by pixel artists Jason Tammemagi, Gyhyom, Mary Safro, and Waneella.[42] In 2012, the Smithsonian Institution museum of Washington created an exhibition called The Art of Video Games, attended by almost 700,000 people.[43][44]

2020s

[edit]

Although some commenters had predicted the decline of "retro" pixel art after a wave of pixel art games in the 2010s, pixel art has continued to remain popular in the current decade.[28] One major contributing factor seems to have been the COVID-19 pandemic, as people around the world spent more time online, playing games, using social media and developing new hobbies. A second contributing factor seems to have been the rise of NFTs, as pixel art became an inexpensive way to produce large numbers of artworks.[45] As the market for NFTs grew rapidly, many pixel artists embraced the new technology as a new source of income. Many notable professional artists also expressed skepticism and disapproval of NFTs, citing environmental factors, pyramid scheme claims, and money laundering as reasons for rejecting offers. One of the most profiled examples of pixel artists expressing opposition to NFTs is Castpixel, citing environmental effects and artificial scarcity.[46] Furthermore, as is the case with other forms of digital art,[47] pixel artists have also discovered many cases of plagiarism and fraud by actors who download pixel art without permission to sell as NFTs. Although the discussion around pixel art theft is not new,[32] the issue has certainly become more controversial with the rise of NFTs.

Perhaps linked to the increased influence and attraction of social media platforms like Twitter, Mastodon, Reddit, and Instagram, older pixel art communities on Pixelation and DeviantArt declined in the 2020s. Discord became an important platform for pixel art communities like Pixel Joint, PAD (Pixel Art Discord), Lospec, and Trigonomicon. In the early fall of 2022, Pixelation announced the closing of its webforum and a transition to Twitter.

Pixel art continued to be a popular style in games across platforms, with releases such as Eastward (2021), Loop Hero (2021), Vampire Survivors (2022), Pizza Tower (2023), Blasphemous 2 (2023), Dave the Diver (2023), Balatro (2024) and Antonblast (2024). Some argued that the recent wave of pixel art games, released thirty years after the release of the SNES, was largely influenced by nostalgia and freedom from publishers, responding to unoriginal stories in modern video game blockbusters and wanting to integrate contemporary themes, such as ecological concerns and representation of queer characters.[48]

Techniques

[edit]

Pixel art typically involves more careful and deliberate placement of pixels compared to other forms of digital art.[26] Artists use different brush sizes (e.g. 1x1 or 2x2 pixels) and a variety of tools, such as free-hand/pencil, lines, and rectangles.[49] One key difference between pixel art and other digital art is that pixel artists tend to apply a single color at a time, avoiding tools such as soft edges, smudging, and blurring.[3] Agreeing on which tools and techniques are considered non-pixel art (NPA) is something that has caused considerable disagreement in the past. For example, applying layers with different filters that adjust hue or light values is considered a non-pixel art technique, but the resulting art may still be considered pixel art if there's a clear foundation of deliberate placement of pixels.[3] To preserve the careful pixel placement, pixel art is preferably stored in a file format utilizing lossless data compression. The JPEG format, for example, is often avoided because of its compression, as it introduces visible artifacts in the image.

Different restrictions are central to pixel art, and these are often traced back to technical limitations of hardware such as Amiga, Commodore 64, NES, and early computers. The two most common restrictions are resolution and palette, and pixel artists often work with a significantly reduced canvas size and number of colors compared to other digital artists. (Lee, p. 276)[citation needed] Examples include Commodore 64 restrictions (320x200 resolution, 16 colors), original ZX Spectrum restrictions (256x192 pixels, 15 colors), and GameBoy restrictions (160x144 pixels, 4 colors).

Some artists start the process of pixelling by drawing line art, while others begin by blocking in simple shapes and big clusters. Traditionally, pixel art was done on a single layer, similar to painting on a canvas, but modern software permits work with multiple layers, potentially adding animation or transparency to the foreground while keeping a static background.

To deal with the various restrictions of pixel art, such as reduced resolution or colors, pixel artists have traditionally employed several techniques specific to the art form. One widely used technique is dithering, commonly using noise or a repeating pattern such as a checkerboard or lines to create a third color when seen from a distance. Other common techniques include anti-aliasing (AA) where strong edges are softened by manually placing pixels, and sub-pixelling, changing the colors of pixels to create an illusion of movement.[3]

Styles

[edit]Because pixel art is a flexible medium, pixel artists can often imitate styles from traditional media, such as impressionism or pointillism in oil painting or cross-hatching in embroidery.[3] Pixel art is not a style itself, but a broad artistic medium.[28] However, there are different styles within pixel art that revolve around pixel placement. One common distinction in style is the use of clusters. A cluster is a field of connected pixels with the same color. The opposite of a cluster is an isolated pixel (1x1) surrounded by pixels of other colors. Cluster size has become an important marker of pixel art styles, where some pixel art uses large clusters and avoids isolated (orphan) pixels, whereas other works use clusters of all sizes in combination with isolated pixels, or even rely primarily on isolated pixels and small clusters for a more grainy, noisy texture. Styles that rely more on small clusters and isolated pixels often have similarities with pointillism and impressionism, whereas pixel art with larger clusters and geometric shapes has similarities with cubism and suprematism. Although some artists have been known for championing a particular style, many pixel artists alternate between different styles in their works.

Genres and subjects

[edit]Pixel art is a flexible medium and shares traditions of figure drawing, landscapes, and abstract with traditional media. However, certain genres have emerged as particularly popular. These genres often overlap, but include:

- Isometric: Pixel art drawn in a near-isometric dimetric projection. Originally used in games to provide a three-dimensional view without using any real three-dimensional processing. Normally drawn with a 1:2 pixel ratio along the X and Y-axis.

- Sprites: Characters and game assets typically drawn in the fashion of platformer games and fighting games such as Streets of Rage or Street Fighter II or JRPGs (Japanese Roleplaying Game) such as Final Fantasy.[3]

- Pixel dolls: Also known as dollz. Sets of pixel art characters, usually with customizable appearance and sets of clothing. Often used as avatars for chatting and forums, or in dress-up games.

- Mock-ups: Concepts for non-existing pixel art games, including a user interface and other game elements. Retro-style mock-ups based on modern games are called 'demakes'.[37]

Differences from Oekaki

[edit]

Oekaki is a form of digital art done at small resolutions that present many similarities with pixel art. However, in Oekaki, the placement of individual pixels is not considered as important compared to the general feel of the artwork, giving it a characteristic "messy" or jagged look.

Software

[edit]Essentially all raster graphics editors can be used in some way for pixel art, some of which include features designed to make the process easier. See Comparison of raster graphics editors for a list of notable raster graphics editors. The following notable programs were designed specifically to facilitate drawing pixel art.

| Software | Description | License | Financial cost | Supported platforms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aseprite | Aseprite features numerous tools for image and animation editing such as layers, frames, tilemaps, command-line interface, Lua scripting, among others. An open-source fork called Libresprite was created before Aseprite became proprietary, which has become a popular free alternative. | Proprietary | Free source code, paid precompiled binaries. | |

| Graphics Gale | Graphics Gale is a Japanese pixel art editor with animation features and a color-based transparency system which game artists extensively used during its early years. It was written in 2005, made freeware in 2017, and last updated in 2018.[50] | Proprietary | Free | |

| GrafX2 | GrafX2 was released in 1996, inspired by the Amiga programs Deluxe Paint and Brilliance. Specialized in 256-color drawing, it includes a broad array of tools and effects suitable for pixel art and 2D video game graphics. | Libre | Free | |

| Pro Motion NG | Pro Motion NG is primarily geared toward drawing art for video games, with features and tools for animation, spritework, and tilesets.[50] | Proprietary | Freemium |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]Books

[edit]- Silber, Daniel (2016). Pixel art for game developers. San Francisco, CA USA: William Pollock. ISBN 978-1-59327-886-1. Archived from the original on 2022-05-25. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- Dawe, Jennifer; Humphries, Matthew (2019). Make Your Own Pixel Art. San Francisco, CA USA: William Pollock. ISBN 978-1-59327-886-1. Archived from the original on 2022-05-25. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- Benjaminsson, Klas (2016a). The Masters Of Pixel Art Volume 1. Göteborg, Sweden: Nicepixel. ISBN 978-91-639-0485-1. Archived from the original on 2021-07-11. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- Benjaminsson, Klas (2016b). The Masters Of Pixel Art Volume 2. Göteborg, Sweden: Nicepixel. ISBN 978-91-639-0486-8. Archived from the original on 2021-05-15. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- Benjaminsson, Klas (2019). The Masters Of Pixel Art Volume 3. Göteborg, Sweden: Nicepixel. ISBN 978-91-519-3539-3. Archived from the original on 2021-06-20. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- Ekilson, Stephen J. (2012). Graphic Design: A New History (2 ed.). Göteborg, Sweden: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-300-17260-7. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

Other relevant sources

[edit]- Goldberg, Adele; Flegal, Robert (December 1982). "ACM president's letter: Pixel Art". Communications of the ACM. 25 (12): 861–862. doi:10.1145/358728.358731. S2CID 5150501.

- Perry, Tekla S.; Wallich, Pau (October 1985). "Inside the PARC: the information architects". IEEE Spectrum. 22 (10): 62–76. Bibcode:1985IEEES..22j..62P. doi:10.1109/MSPEC.1985.6370844. S2CID 36397557.

References

[edit]- ^ "Grand dictionnaire terminologique - art du pixel". gdt.oqlf.gouv.qc.ca (in Canadian French). Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- ^ a b c "What is Pixel Art? - Definition from Techopedia". 2022-05-26. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 2022-09-10.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lee, Cindy (2021). "Chapter 14: Best Practices for Pixel Art". In Dillon, Roberto (ed.). The Digital Gaming Handbook (1st ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 275–286. ISBN 978-0-367-22384-7.

- ^ Silber (2016), p. 11, preface.

- ^ Wilson Whiskey animated Times Square sign (1937), 2 June 2024, retrieved 2025-08-04

- ^ Goldberg & Flegal (1982), pp. 861–862.

- ^ Perry & Wallich (1985), pp. 62–76.

- ^ a b Wolf, Mark J. P.; Perron, Bernard (2003). The Video Game Theory Reader. New York and London: Routledge. pp. 47–64. ISBN 0-415-96578-0.

- ^ Swalwell, Melania; Garda, Maria B. (15 February 2019). "Art, Maths, Electronics and Micros: The Late Work of Stan Ostoja-Kotkowski". Arts. 8 (1): 23. doi:10.3390/arts8010023. hdl:1959.3/448415.

- ^ Clark, Sean, and Geoff Davis. "Revisiting and Re-presenting 1980s Micro Computer Art." (2021).

- ^ a b Benjaminsson, Klas (2020). The Masters of Pixel Art volume 3. Nicepixel Publications. pp. 51, 140, 156, 198. ISBN 978-91-519-3539-3.

- ^ a b Benjaminsson, Klas (2020). The Masters of Pixel Art volume 1. Nicepixel Publications. pp. 7, 52, 77. ISBN 978-91-639-0485-1.

- ^ Benjaminsson, Klas (2017). Masters of Pixel Art volume 2. Nicepixel Publications. p. 56. ISBN 978-91-639-0486-8.

- ^ a b c d Dewey, Caitlin (14 October 2014). "Nostalgia, Norwegian money and the unlikely resurgence of pixel art". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ Benjaminsson, Klas (2020). The Masters of Pixel Art volume 1. Nicepixel Publications. p. 52, 174. ISBN 978-91-639-0485-1.

- ^ Benjaminsson, Klas (2020). The Masters of Pixel Art volume 3. Nicepixel Publications. p. 51. ISBN 978-91-519-3539-3.

- ^ Benjaminsson, Klas (2020). The Masters of Pixel Art volume 1. Nicepixel Publications. p. 14, 45. ISBN 978-91-639-0485-1.

- ^ Benjaminsson, Klas (2020). The Masters of Pixel Art volume 1. Nicepixel Publications. p. 130, 133, 177. ISBN 978-91-639-0485-1.

- ^ "Art, One Click at a Time". Pogue's Posts Blog. 2006-09-15. Retrieved 2022-09-03.

- ^ "Weekly art websites: pixel art". The Independent. 2010-08-30. Retrieved 2022-09-03.

- ^ a b Benjaminsson, Klas (2020). The Masters of Pixel Art volume 3. Nicepixel Publications. p. 194. ISBN 978-91-519-3539-3.

- ^ a b Benjaminsson, Klas (2020). The Masters of Pixel Art volume 3. Nicepixel Publications. p. 39, 40, 115. ISBN 978-91-519-3539-3.

- ^ Benjaminsson, Klas (2017). Masters of Pixel Art volume 2. Nicepixel Publications. p. 14, 129, 155. ISBN 978-91-639-0486-8.

- ^ "Creativity Bytes: A Brief Guide To Pixel Art". Vice.com. 23 February 2011. Retrieved 2022-09-03.

- ^ "Nintendo SNES Classic Mini review: amazing games marred by hardware oversights". Wired UK. ISSN 1357-0978. Retrieved 2022-09-03.

- ^ a b "Talking Shop: Shovel Knight's Pixel Artist". GamesIndustry.biz. 2013-04-10. Retrieved 2022-09-03.

- ^ Sucasas, Ángel Luis (2018-07-07). ""No necesitamos el fotorrealismo para gozar de los videojuegos"". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 2022-09-03.

- ^ a b c Moher, Aidan. "The Pixel Art Revolution Will Be Televised". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2022-09-03.

- ^ "Owlboy: the indie platformer that took 10 years to build". the Guardian. 2016-11-07. Retrieved 2022-09-03.

- ^ "Sword and Sworcery – review". the Guardian. 2011-04-16. Retrieved 2022-09-03.

- ^ "Futuristic Landscapes Get a Retro Look, Thanks to Pixel Art". Vice.com. 12 December 2016. Retrieved 2022-09-03.

- ^ a b "An E-Gallery Of Video Games' Finest Pixel Art, But Who Owns It?". Vice.com. December 2013. Retrieved 2022-09-03.

- ^ Benjaminsson, Klas (2020). The Masters of Pixel Art volume 1. Nicepixel Publications. p. 191. ISBN 978-91-639-0485-1.

- ^ Benjaminsson, Klas (2017). Masters of Pixel Art volume 2. Nicepixel Publications. p. 57, 181. ISBN 978-91-639-0486-8.

- ^ Benjaminsson, Klas (2017). Masters of Pixel Art volume 2. Nicepixel Publications. p. 57, 159, 185. ISBN 978-91-639-0486-8.

- ^ "Watch 'The Simpsons' Totally Reimagined as Stunning Pixel Art". Time. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

- ^ a b "Creativity Bytes: A Brief Guide To Pixel Art". Vice.com. 23 February 2011. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

- ^ "Weekly art websites: pixel art". The Independent. 2010-08-30. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

- ^ "Intricate Pixel Art Peels Back The Layers Of Imaginary Worlds". Vice.com. 19 September 2014. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

- ^ "Si las series de hoy se parecieran a los videjouegos de los 90". Verne (in Spanish). 2018-01-14. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

- ^ "Pixel art hors de prix : un portrait du Dalaï-Lama composé de Rubik's Cubes vendu 450.000 euros". LEFIGARO (in French). 2021-07-06. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

- ^ Liptak, Andrew (2018-03-11). "Ernie Cline's Ready Player One gets a tiny adaptation in this music video". The Verge. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

- ^ "The Art of Video Games | Smithsonian American Art Museum". americanart.si.edu. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

- ^ "Here's how many people saw The Smithsonian's Art of Games". finance.yahoo.com. 2 October 2012. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

- ^ Hughes, Stephanie (2021-08-19). "Reeling from the pandemic, more artists turn to augmented reality NFTs". Financial Post. Retrieved 2022-09-03.

- ^ Jiang, Sisi (2021-11-10). "These Game Developers Are Choosing To Turn Down NFT Money". Kotaku Australia. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved 2022-09-03.

- ^ "'Huge mess of theft and fraud:' artists sound alarm as NFT crime proliferates". the Guardian. 2022-01-29. Retrieved 2022-09-03.

- ^ "La console Super Nintendo inspire toujours des jeux vidéo modernes au design rétro, trente ans après sa sortie". Le Monde.fr (in French). 2022-06-06. Retrieved 2022-09-03.

- ^ Silber, D. (2015). Pixel art for game developers. CRC Press.

- ^ a b Dawe & Humphries (2019), p. 18, preface.

External links

[edit]Pixel art

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition and Characteristics

Pixel art is a form of digital art where images are created and edited at the individual pixel level within a raster graphics framework, treating each pixel—the smallest addressable element of an image—as a deliberate building block. This approach emphasizes manual control over every pixel's color and position to construct visuals, often constrained by low resolutions such as 128x128 or smaller, which originated from hardware limitations but now serve as a stylistic choice.[6][7] Core characteristics include restricted color palettes, typically limited to 16 to 256 colors, which force artists to select hues strategically for maximum expressiveness and to evoke a retro aesthetic. Techniques like dithering, where adjacent pixels of varying colors are alternated to simulate gradients, shading, or additional tones, and anti-aliasing, which softens edges through strategic pixel blending, create illusions of smoothness and depth on the inherently blocky grid. Each pixel holds significant meaning, contributing to the composition's overall form without reliance on automated tools, resulting in a crisp, stylized appearance that prioritizes precision over fluidity.[8][7][9] Pixel art differs fundamentally from vector graphics, which define shapes using scalable mathematical paths and remain sharp at any size, whereas pixel art's fixed raster grid leads to pixelation and loss of detail when enlarged, enhancing its characteristic blockiness. In contrast to high-resolution digital painting, which employs brush-based tools for continuous, layered strokes mimicking traditional media, pixel art demands pixel-by-pixel "pushing" for edits, underscoring its grid-bound, low-fidelity ethos over photorealistic rendering.[10][6][11]Historical Significance

Pixel art holds a foundational role in the development of early computer graphics, serving as the primary visual medium for digital displays constrained by limited processing power and memory in the late 20th century.[12] Its enduring cultural impact is evident in contemporary design, where it evokes nostalgia for retro computing eras while inspiring modern aesthetics in video games, animations, and graphic interfaces that prioritize simplicity and charm.[13] A key milestone in pixel art's significance lies in its transformation from a technical limitation to a deliberate artistic choice, allowing creators to embrace low-resolution constraints as a means to innovate within defined boundaries. This shift profoundly influenced game design aesthetics, where precise pixel placement—often termed the "pixel perfect" philosophy—fostered creativity by turning restrictions into opportunities for stylized expression and efficient storytelling.[14] Furthermore, pixel art has played a crucial role in preserving retro computing heritage, with emulators and archival projects maintaining access to thousands of artifacts from early systems, ensuring that this visual language remains a touchstone for understanding technological evolution.[15] Beyond its aesthetic contributions, pixel art bridged the disciplines of art and programming, encouraging interdisciplinary collaboration and giving rise to vibrant subcultures such as the demoscene, where participants craft real-time audiovisual demonstrations showcasing pixel-based graphics under severe size and hardware limits.[15] Its prevalence underscores this legacy: virtually all official Game Boy titles, released between 1989 and 2001, relied exclusively on pixel art due to the console's monochrome display capabilities, establishing it as a cornerstone of portable gaming culture.[16]History

Origins in Computing

The origins of pixel art are rooted in the technical constraints and experimental innovations of early computing hardware during the 1950s and 1960s, when monochrome displays and rudimentary graphics systems first enabled the visualization of digital images. The Whirlwind computer, developed at MIT and operational by 1951, marked a pivotal advancement as the first digital computer to incorporate a real-time video display using a cathode-ray tube (CRT), allowing for immediate graphical output in monochrome though primarily through vector-based rendering of lines and points.[17] Early CRT experiments in the same era, such as those at research institutions, focused on basic oscilloscope screens to depict simple patterns and data visualizations, establishing the foundation for pixel-like discrete elements on screens limited by low resolution and binary color capabilities.[18] A key conceptual breakthrough came in the mid-1960s with the shift toward raster graphics, which directly influenced pixel art by representing images as grids of individually addressable picture elements (pixels). In 1963, Ivan Sutherland's Sketchpad system on the TX-2 computer introduced interactive graphical editing, enabling users to draw and manipulate lines and shapes in real time on a vector display, which laid the groundwork for later pixel-based manipulation by demonstrating direct human-computer visual interaction.[19] Building on this, A. Michael Noll at Bell Telephone Laboratories developed one of the earliest raster-scanned displays in the late 1960s, using software-driven scan conversion to generate bitmap-like images on CRTs, allowing for the rendering of filled areas and patterns that approximated modern pixel grids.[20] These innovations transitioned computing from line-drawn vectors to sampled, grid-based representations, essential for pixel art's discrete aesthetic. Non-commercial experiments during the 1960s further explored visual potential on minicomputers, often by hobbyists and researchers pushing hardware limits. On the PDP-1 minicomputer introduced in 1960, Steve Russell and collaborators created Spacewar! in 1962, featuring rudimentary spaceship graphics and effects displayed on an oscilloscope in monochrome, highlighting the creative use of limited pixels for dynamic visuals in a non-commercial context.[21] This era also saw a gradual shift from vector to raster approaches in research hardware, as systems like those at Bell Labs began incorporating frame buffers to store and refresh pixel data, though affordability remained a barrier until the 1970s.[20] The first intentional creations resembling pixel art appeared in 1960s plotter-based computer art, where algorithms generated abstract, grid-like patterns output as line drawings on mechanical plotters, mimicking pixel mosaics through systematic point-to-point plotting. Pioneers like A. Michael Noll produced such works as early as 1962 at Bell Labs, using the IBM 7090 to compute probabilistic line compositions that evoked ordered chaos in a pixel-esque fashion.[22] Similarly, Georg Nees exhibited algorithmic plotter drawings in 1965, treating the plotter as a "drawing machine" to create geometric abstractions that prefigured pixel art's constrained palette and resolution.[23] However, true pixel art as a distinct form emerged only with the widespread availability of affordable raster displays in the following decade, enabling direct on-screen pixel editing beyond plotted approximations.[24]Early Commercial Use (1970s–1980s)

The commercialization of pixel art began in the 1970s with the advent of arcade and home video game systems, where hardware constraints necessitated the creation of simple, blocky raster graphics composed of individual pixels. One of the earliest examples was Atari's Pong, released in 1972 as an arcade game, which featured basic two-dimensional black-and-white graphics simulating a table tennis match on a raster display, marking an initial foray into pixel-based visuals driven by analog circuitry limitations.[25] This proto-pixel art approach laid groundwork for more complex designs, as Pong's success—selling over 8,000 arcade units by 1974—spurred the industry toward pixel-rendered elements in commercial entertainment.[26] The Atari 2600, launched in 1977, further propelled pixel art into home consoles with its 160x192 pixel resolution (NTSC) and a 128-color palette, though on-screen display was restricted to about four colors per scanline to manage hardware limits.[27] Games like Combat and Space Invaders variants showcased rudimentary sprites—movable pixel objects—programmed directly in assembly code, emphasizing the era's focus on efficient pixel manipulation for gameplay. Simultaneously, the Apple II computer, released the same year, enabled sprite-based graphics through software, supporting a high-resolution mode of 280x192 pixels in monochrome with color achieved via NTSC artifacting, allowing developers to create animated pixel elements for educational and gaming software.[28] By the 1980s, pixel art flourished amid a console and home computer boom, with systems imposing strict palette and resolution limits that fostered innovative techniques. The Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), known as the Famicom in Japan and released in 1983, utilized 8x8 pixel tiles for backgrounds and sprites sized 8x8 or 8x16 pixels, drawing from a 52-color palette but limiting to 16 colors on screen per area to fit within 2KB of video RAM.[29] Iconic titles like Super Mario Bros. (1985) exemplified this, employing precisely crafted sprites for Mario—composed of 12x16 pixels in key poses—and environmental tiles, where developers optimized dithering patterns to simulate gradients and shading within the 16-color constraint, enhancing visual depth without exceeding hardware bounds.[29] Home computers like the ZX Spectrum, introduced in 1982, offered a 256x192 pixel resolution with 15 colors (from an 8-color base with bright variants), but attribute clash—where adjacent pixels couldn't differ greatly in color—compelled artists to use strategic pixel placement and dithering for illusions of additional hues in games such as Manic Miner.[30] In adventure games, Sierra On-Line's King's Quest (1984), built on the AGI engine, rendered scenes at 160x200 pixels using a 16-color CGA palette, with vector-drawn backgrounds converted to pixels and animated sprites for characters, allowing larger, explorable pixel environments despite the era's memory restrictions of under 1MB total.[31] Artists at Sierra, including Roberta Williams, often iterated designs manually on graph paper before digitizing, adapting to palette limits by employing dithering to blend colors and create textured landscapes.[31] The decade also saw the origins of the demoscene, emerging from European cracking groups in the mid-1980s who modified commercial software to include custom pixel art intros, showcasing high-resolution graphics within tight file sizes on platforms like the Commodore 64.[32] These "cracktros" featured scrolling text, animated sprites, and dithered effects, pushing pixel art's creative boundaries as a non-commercial counterpoint to mainstream games, with groups competing to impress via efficient code and artistry. Overall, the 1970s–1980s era's hardware limitations—such as 16-color palettes and low resolutions—drove pixel art's distinctive aesthetic, where dithering emerged as a core technique to approximate continuous tones by interleaving available colors at the pixel level, simulating richer visuals on CRT displays.[29]Mainstream Adoption (1990s–2000s)

During the 1990s, pixel art reached a peak in mainstream video games with the release of the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES) in 1990, which supported a native resolution of 256x224 pixels and innovative graphical modes like Mode 7 for rotating and scaling backgrounds to create pseudo-3D effects in titles such as Super Mario World.[33][34][35] This era saw pixel art evolve into highly detailed sprites and environments, exemplified by role-playing games like Final Fantasy VI (1994), where artists crafted intricate character portraits and animated sequences that maximized the console's 256-color palette for expressive storytelling.[36] Concurrently, pixel art began emerging on the World Wide Web through animated GIFs, which became a staple for early website graphics due to their compact file size and looping capabilities, enabling simple animations in personal pages and early online communities.[37] In the 2000s, handheld consoles sustained pixel art's prominence, particularly with the Game Boy Advance (launched 2001), featuring a 240x160 resolution that allowed for vibrant, colorful sprites in portable RPGs and platformers like The Legend of Zelda: The Minish Cap.[38][39] Indie developers further popularized the style via Flash games on platforms like Newgrounds, where pixel art enabled accessible, browser-based experiences such as Fancy Pants Adventures (2005), blending retro aesthetics with modern interactivity.[40] However, the decade marked a decline in mainstream adoption as 3D graphics dominated console titles from the PlayStation 2 and Xbox eras, relegating pixel art to niche applications, though it persisted through retro game emulators that preserved and replayed 8-bit and 16-bit classics on PCs.[41][42] Key trends included pixel art's expansion into animations for music videos and idents, with experimental low-resolution visuals appearing in 1990s broadcast media to evoke digital futurism. Publications and online resources proliferated, offering tutorials on techniques like dithering and palette optimization, while communities like Pixel Joint—established in 2004—fostered sharing and challenges that sustained artist engagement amid the shift to higher-fidelity graphics.[43][44]Digital Revival (2010s–2020s)

In the 2010s, pixel art experienced a notable revival within the indie game development community, where its retro aesthetic provided a cost-effective and nostalgic alternative to high-fidelity graphics, appealing to both developers and players seeking authenticity in an era dominated by photorealistic visuals. Titles such as Undertale (2015), created by Toby Fox, utilized pixel art to craft emotionally resonant narratives and characters, achieving critical acclaim and commercial success that highlighted the style's enduring charm. Similarly, Celeste (2018), developed by Extremely OK Games, employed precise pixel art animations to enhance its challenging platforming mechanics, earning awards for its artistic direction and contributing to the broader indie renaissance.[45] This resurgence was fueled by platforms like Steam and itch.io, which democratized distribution for small teams, allowing pixel art to flourish as a deliberate stylistic choice rather than a technical limitation.[46] Mobile gaming further amplified this revival, with pixel art enabling intricate designs optimized for touch interfaces and smaller screens. For instance, Terraria (2011, mobile port 2013 by Codeglue and Re-Logic) delivered expansive sandbox exploration through layered pixel sprites, selling millions and demonstrating the style's adaptability to portable devices.[47] By the late 2010s, pixel art had become a hallmark of indie innovation, blending simplicity with expressive depth to stand out in crowded marketplaces.[47] Entering the 2020s, pixel art trends evolved with emerging technologies, integrating into blockchain-based projects like CryptoPunks (launched 2017 by Larva Labs), a collection of 10,000 procedurally generated 24x24 pixel characters that pioneered NFTs and revitalized pixel art as a valuable digital asset, with floor prices surging to over $200,000 in July 2025, though as of November 2025, the floor price is approximately $93,000 (about 30 ETH).[48][49] AI-assisted tools began emerging around 2023, such as fine-tuned Stable Diffusion models and Adobe Firefly's generative features in Photoshop beta, enabling faster iteration on pixel sprites while preserving artistic control.[50] Virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) applications also incorporated pixel art for immersive experiences, with titles on platforms like itch.io combining low-res aesthetics with spatial interactions to evoke retro futurism.[51] Key developments in the 2020s included pixel art's presence in esports, particularly through customizable Minecraft skins—blocky pixel-based avatars used in competitive events like the Minecraft Championship series, where they enhance player identity without compromising performance. By 2025, educational apps saw substantial growth, with tools like Code.org's Sprite Lab teaching coding fundamentals through pixel art creation, fostering skills in logic and design among young learners. Steam data for 2024 indicates that pixel art was a popular tag among the nearly 19,000 new game releases, particularly in the indie sector, with thousands of titles featuring the style.[52][53] A distinctive innovation during this period was "HD pixel art" hybrids, exemplified by Square Enix's HD-2D technique, which scales low-resolution pixel assets to high-resolution displays using advanced 3D modeling, dynamic lighting, and environmental effects to create visually striking results without losing the original pixelated essence, as seen in games like Octopath Traveler (2018) and Live A Live (2022). This approach bridged retro roots with modern hardware capabilities, expanding pixel art's applicability across genres.[54][55]Techniques

Creation Methods

Pixel art creation typically begins with planning the resolution and gathering references to establish the scope and inspiration for the piece. Artists often select standard low resolutions such as 32x32 pixels for tiles or sprites to maintain the characteristic blocky aesthetic while fitting technical constraints of early computing hardware. Reference gathering involves studying real-world subjects or existing artworks to inform shapes, proportions, and color choices, ensuring the final output aligns with the intended style without exceeding palette limits. This phase transitions into rough sketching on a higher-resolution canvas, where broad strokes outline the composition before downscaling to the target pixel grid. The core workflow proceeds through pixel-by-pixel editing, where individual pixels are placed and adjusted to build forms and details. This hands-on method allows precise control, starting with basic silhouettes and layering in shading or highlights using a limited color palette, typically 16 to 256 colors. Iterative refinement follows, involving zooming in for fine adjustments, testing visibility at native scale, and repeating cycles of addition and subtraction to achieve balance—often requiring multiple passes to correct inconsistencies. Once the base image is complete, colors are indexed to a fixed palette, mapping shades to specific slots for optimization and variations like palette swapping, which reassigns colors across frames or assets to create diversity without redrawing.[6] Palette swapping is particularly useful for generating enemy variants or environmental changes by altering hue mappings in an indexed image.[56] Key techniques enhance visual depth within these constraints. Dithering simulates gradients by alternating pixels of two or more colors in patterns; ordered dithering uses structured grids like checkerboards for predictable blends, while random dithering scatters pixels for a noisier, organic effect, both helping to expand perceived color range without additional shades. Anti-aliasing smooths edges using sub-pixel tricks, such as placing intermediate colors along boundaries to reduce jaggedness—for instance, blending a dark outline with a lighter adjacent pixel to mimic curves—though over-application can lead to unintended blurring that softens the crisp pixelated look.[57][58] For animation, workflows incorporate onion skinning, a transparency overlay of previous and next frames to guide consistent motion across sequences. Artists plan cycles with 4 to 8 frames for looping actions like walking, focusing on key poses (contact, down, passing, up) and in-betweens to ensure smooth transitions without redundancy. This frame-by-frame approach demands iterative testing for timing and fluidity, often revealing pitfalls like inconsistent line weights or excessive anti-aliasing that muddies movement. Detailed character animations may take 10 to 20 hours, depending on complexity, highlighting the labor-intensive nature of the medium.[59][60][61]Artistic Styles

Pixel art encompasses a variety of artistic styles that leverage the medium's inherent constraints to create distinct visual effects. Major styles include isometric pixel art, which simulates three-dimensional depth through a specific projection technique where objects are rendered at a 30-degree angle to convey spatial relationships without true 3D modeling.[62] Voxel-like approaches extend this into a pseudo-3D form, treating pixels as volumetric units to build blocky, low-poly structures that emphasize geometric solidity and modularity.[63] Representational styles dominate early pixel art, aiming to depict recognizable subjects like characters or landscapes with precise detail within grid limitations, while abstract variants prioritize patterns, colors, and forms over literal depiction, often exploring non-figurative compositions.[64] Influences from broader art movements have shaped pixel aesthetics, with cubism's emphasis on fragmented geometry and multiple perspectives resonating in pixel art's grid-based deconstruction of forms, adapting angular fragmentation to digital blocks for a sense of simultaneity and abstraction.[64] Pop art's celebration of consumer culture and bold, flat colors similarly informs pixel works that incorporate iconic motifs from media and advertising, rendered in simplified, high-contrast palettes to evoke nostalgia and irony.[65] These styles evolved from hardware-imposed limitations in early computing, where low resolution forced deliberate pixel placement, to intentional choices in contemporary practice that embrace the grid as an expressive tool. Aesthetics in pixel art have diversified between "clean" modern interpretations, featuring sharp edges, smooth gradients, and precise lines for a polished, scalable look, and "crunchy" retro styles that retain jaggy artifacts, dithering, and scanline effects to mimic vintage displays and add tactile grit.[66] Color theory plays a pivotal role, particularly through limited palettes that restrict hues to evoke specific emotions—such as cool metallics for industrial tension or pastel sets for calm whimsy—enhancing cohesion and forcing creative use of contrast, saturation, and value within few colors.[67] Unique examples highlight pixel art's versatility, including the use of Dutch angles—tilted perspectives originally from film to induce unease and dynamism—adapted to pixel grids for off-kilter compositions that inject motion and tension into static scenes.[68] Hybrid styles blend pixel elements with vector graphics, combining the former's discrete blocks for texture with the latter's smooth scalability to produce layered, striking visuals that bridge retro charm and contemporary precision.[69] By the 2010s, "pixel gore" emerged in horror genres, employing exaggerated, blocky blood and viscera to amplify visceral impact through the medium's stylized limitations, as seen in games like Blasphemous.[42]Genres and Common Subjects

Pixel art encompasses a variety of genres that leverage its blocky aesthetic to depict imaginative and realistic scenes. Primary genres include fantasy, often featuring elements like elves, dragons, enchanted forests, and castles in RPG tilesets, which evoke medieval or mythical worlds constrained by limited color palettes and resolutions.[70] Sci-fi is another prominent genre, showcasing spaceships, aliens, futuristic cityscapes, and underground tunnel systems inspired by retro video games.[70] Everyday scenes form a more grounded category, portraying cityscapes, seascapes at sunset, food items, or domestic objects to capture mundane life in a stylized, nostalgic form.[70] Common subjects in pixel art revolve around functional and narrative elements, particularly characters rendered as sprites with idle animations to convey personality or movement within tight pixel grids.[71] Environments, such as parallax scrolling backgrounds depicting dark woods, dungeons, or natural landscapes, provide immersive settings that enhance spatial depth despite resolution limits.[72] UI elements like icons, heads-up displays (HUDs), and buttons are also frequent, designed for clarity and integration into interactive digital interfaces.[73] Emerging trends in pixel art include horror, where pixelated blood effects and eerie silhouettes build tension through distortion and shadow play, as seen in indie games blending retro visuals with unsettling narratives.[74] Abstract forms, such as glitch art, manipulate digital errors to create chaotic, fragmented compositions that challenge traditional representation.[74] Many documented pixel art archives and datasets focus on game-related subjects, like platformer sprites and tilesets, underscoring its prevalence in interactive media.[75] A unique aspect of pixel art lies in adapting real-world subjects to its constraints, with artists attempting photorealism in limited spaces, such as 64x64 portraits that approximate facial details through careful dithering and color selection.[76] These efforts highlight how pixel limitations foster creative interpretation over exact replication.[77]Tools and Software

Digital Software

Digital software for pixel art encompasses a range of applications designed to facilitate the creation, editing, and animation of low-resolution graphics, often emphasizing grid-based drawing tools, color palette management, and frame-by-frame workflows. These tools have evolved to support both professional and hobbyist artists, enabling precise control over individual pixels while integrating modern features like layer organization and export options for game development. Key programs cater to different needs, from dedicated sprite editors to adaptable general-purpose graphics software. Aseprite, released in 2016, stands out as a leading dedicated pixel art tool, particularly for indie game developers creating 2D animations and sprites. Widely adopted in indie development, it supports layer and frame management, allowing users to compose complex artwork with separate concepts for organization and playback. Onion skinning enables viewing adjacent frames as semi-transparent overlays for smooth animation referencing, while a built-in palette editor permits copying, pasting, and resizing color sets with alpha channel adjustments. Export capabilities include PNG sequences for transparency, animated GIFs, and sprite sheets in PNG/JSON formats, making it ideal for integrating assets into game engines.[78] A free, open-source alternative is LibreSprite, a 2022 fork of Aseprite that retains core features like animation tools, layers, and palette editing while being accessible without cost.[79] GraphicsGale, a Windows-focused application now available as freeware since 2017, specializes in spriting and pixel animation with real-time preview capabilities. It features multiple layers per frame for detailed composition, onion skinning for animation guidance, and support for indexed color modes common in pixel art. The software allows batch editing of frames and exports to formats like PNG, emphasizing efficiency for animation workflows on limited hardware.[80] For broader graphic editing, Adobe Photoshop serves as a versatile option for pixel art when configured with pixel-specific brushes and grid snapping, though it requires plugins or custom setups for optimal low-resolution work. Its robust layer system and non-destructive editing tools enable precise pixel manipulation, with exports to PNG preserving transparency essential for game sprites. Free alternatives like GIMP offer similar layer-based editing and PNG export, making it accessible for pixel art creation without specialized hardware dependencies. Browser-based Piskel provides a lightweight, no-install option for quick sprite and animation editing, supporting layers and frame timelines for retro-style graphics.[81][82] The evolution of pixel art software traces back to 1990s programs like Deluxe Paint, which dominated sprite creation on platforms such as the Amiga with tools for bitmap editing and palette limitation, and early versions of Photoshop introduced in 1990 for photo-realistic adjustments adaptable to pixels. By the 2020s, tools have incorporated AI integrations, such as Krita's AI Diffusion plugin for generative assistance in image creation, enhancing workflows with automated elements like pattern suggestions while maintaining artist control. These advancements build on foundational paint programs like Microsoft Paint, shifting toward specialized editors with scripting support for batch operations. Workflow integration in modern pixel art software emphasizes layer systems for non-destructive edits and scripting for automation, as seen in Aseprite's Lua-based extensions for custom tools and repetitive tasks like palette swaps. Palette editors and onion skinning streamline color management and animation, while export formats ensure compatibility with development pipelines, allowing artists to iterate efficiently from concept to final assets.Hardware and Emulation Tools

Pixel art's development was profoundly shaped by the hardware constraints of early consoles, such as the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), which featured an 8-bit Ricoh 2A03 processor operating at 1.79 MHz. This setup limited graphical output to a 256x240 resolution via its picture processing unit (PPU), with a palette of 54 colors but only 25 usable simultaneously on screen, compelling artists to employ techniques like dithering to simulate gradients within these bounds. Sprite handling was further restricted to 64 total, with no more than eight per scanline to avoid flicker, directly influencing the blocky, optimized aesthetics seen in titles like Metroid.[29][83][84] Contemporary hardware recreations and input devices extend these historical platforms for modern pixel art creation. Raspberry Pi single-board computers, for instance, support projects like the official Pixel Art Editor, where users program LED matrices or displays to generate and animate low-resolution graphics, evoking 8-bit eras while adding programmability. Tablets equipped with styluses, such as Wacom Intuos or XP-Pen Artist models, offer pixel-level precision through pressure-sensitive tips and high tracking resolution (up to 8,192 levels), allowing artists to navigate grid-based editors with natural hand movements akin to traditional inking.[85][86] Emulation tools bridge original hardware limitations with current technology, enabling faithful reproduction of pixel art experiences. RetroArch serves as a versatile, open-source frontend that integrates cores for systems like the NES and Game Boy, running classic games on PCs, consoles, or mobiles while preserving sprite priorities and color palettes. Online emulators like JSNES, a pure JavaScript implementation, allow browser-based playback of NES ROMs, facilitating quick access to pixel art demos without installation. Hardware-focused solutions, such as the 2021 Analogue Pocket, employ field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) to natively execute Game Boy cartridges on a 3.5-inch, 1600x1440 LCD with 615 ppi density, accurately replicating pixel grids, backlight diffusion, and scanline effects absent in software emulation.[87][88][89] For viewing, modern setups often pair LCD monitors with shader-based CRT filters in emulators or standalone software, simulating the phosphor glow, scanlines, and slight defocus of cathode-ray tubes to mitigate the starkness of digital pixels. Emerging applications in VR headsets, like custom shaders in platforms such as Oculus Quest, approximate low-res displays by rendering pixelated textures at reduced effective resolutions, though adoption remains niche due to headset pixel densities exceeding 20 pixels per degree.[90][91] Key challenges persist in adapting pixel art to these tools, particularly scaling artifacts when upscaling low-res assets to HD resolutions, which introduce bilinear blurring or aliasing that distorts intended sharp edges. Emulation accuracy for analog phenomena like color bleeding—caused by CRT phosphor overlap—remains critical, as modern LCDs lack this natural blending, potentially altering artistic choices made under original hardware constraints.[92]AI-Powered Pixel Art Generators

As of late 2025 and early 2026, artificial intelligence has introduced powerful generative tools specifically suited for creating 2D pixel art assets used in game development. These tools are particularly popular among indie game developers due to their ability to produce high-quality sprites, tilesets, backgrounds, and other assets quickly and with minimal manual effort.- Leonardo.AI is highly regarded for its specialized pixel art models, which deliver strong consistency in artistic style and character appearance across generations. The platform includes a canvas editor that supports direct refinement and editing of game assets such as tilesets, sprites, and backgrounds, making it well-suited for integration into game development pipelines.[93]

- Recraft.AI excels in producing clean, high-quality pixel art alongside vector-based outputs. It is frequently praised for generating accurate, pixel-perfect results that align closely with the aesthetic requirements of retro and classic game assets.[94]

- Midjourney (accessible via Discord or its web interface) can generate effective pixel art when guided by detailed prompts specifying styles such as 16-bit or 32-bit. It is particularly useful for rapid concepting and ideation of game assets.[95]