Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

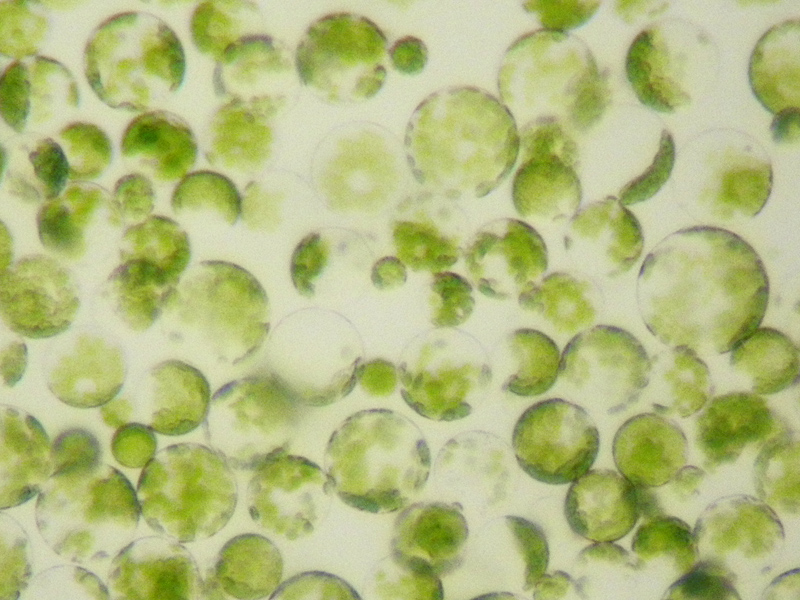

Protoplast

View on Wikipedia

Protoplast (from Ancient Greek πρωτόπλαστος (prōtóplastos) 'first-formed'), is a biological term coined by Hanstein in 1880 to refer to the entire cell, excluding the cell wall.[1][2] Protoplasts can be generated by stripping the cell wall from plant,[3] bacterial,[4][5] or fungal cells[5][6] by mechanical, chemical or enzymatic means.

Protoplasts differ from spheroplasts in that their cell wall has been completely removed.[4][5] Spheroplasts retain part of their cell wall.[7] In the case of Gram-negative bacterial spheroplasts, for example, the peptidoglycan component of the cell wall has been removed but the outer membrane component has not.[4][5]

Enzymes for the preparation of protoplasts

[edit]Cell walls are made of a variety of polysaccharides. Protoplasts can be made by degrading cell walls with a mixture of the appropriate polysaccharide-degrading enzymes:

| Type of cell | Enzyme |

|---|---|

| Plant cells | Cellulase, pectinase, xylanase[3] |

| Gram-positive bacteria | Lysozyme, N,O-diacetylmuramidase, lysostaphin[4] |

| Fungal cells | Chitinase[6] |

During and subsequent to digestion of the cell wall, the protoplast becomes very sensitive to osmotic stress. This means cell wall digestion and protoplast storage must be done in an isotonic solution to prevent rupture of the plasma membrane.[citation needed]

Uses for protoplasts

[edit]

Protoplasts can be used to study membrane biology, including the uptake of macromolecules and viruses . These are also used in somaclonal variation.

Protoplasts are widely used for DNA transformation (for making genetically modified organisms), since the cell wall would otherwise block the passage of DNA into the cell.[3] In the case of plant cells, protoplasts may be regenerated into whole plants first by growing into a group of plant cells that develops into a callus and then by regeneration of shoots (caulogenesis) from the callus using plant tissue culture methods.[8] Growth of protoplasts into callus and regeneration of shoots requires the proper balance of plant growth regulators in the tissue culture medium that must be customized for each species of plant.[9][10] Unlike protoplasts from vascular plants, protoplasts from mosses, such as Physcomitrella patens, do not need phytohormones for regeneration, nor do they form a callus during regeneration. Instead, they regenerate directly into the filamentous protonema, mimicking a germinating moss spore.[11]

Protoplasts may also be used for plant breeding, using a technique called protoplast fusion. Protoplasts from different species are induced to fuse by using an electric field or a solution of polyethylene glycol.[12] This technique may be used to generate somatic hybrids in tissue culture.[citation needed]

Additionally, protoplasts of plants expressing fluorescent proteins in certain cells may be used for Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting (FACS), where only cells fluorescing a selected wavelength are retained. Among other things, this technique is used to isolate specific cell types (e.g., guard cells from leaves, pericycle cells from roots) for further investigations, such as transcriptomics.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ von Hanstein JL (1880). Das Protoplasma als Träger der pflanzlichen und thierischen Lebensverrichtungen für Laien und Fachgenossen. Heidelberg: Selbstverlag.

- ^ Sharp LW (1921). An introduction to cytology. New York: McGraw-Hill book Company, Incorporated. p. 24.

- ^ a b c Davey MR, Anthony P, Power JB, Lowe KC (March 2005). "Plant protoplasts: status and biotechnological perspectives". Biotechnology Advances. 23 (2): 131–171. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2004.09.008. PMID 15694124.

- ^ a b c d Cushnie TP, O'Driscoll NH, Lamb AJ (December 2016). "Morphological and ultrastructural changes in bacterial cells as an indicator of antibacterial mechanism of action". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 73 (23): 4471–4492. doi:10.1007/s00018-016-2302-2. hdl:10059/2129. PMC 11108400. PMID 27392605. S2CID 2065821.

- ^ a b c d "Protoplasts and spheroplasts". www.encyclopedia.com. Encyclopedia.com. 2016. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ a b Dahiya N, Tewari R, Hoondal GS (August 2006). "Biotechnological aspects of chitinolytic enzymes: a review". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 71 (6): 773–782. doi:10.1007/s00253-005-0183-7. PMID 16249876. S2CID 852042.

- ^ "Definition of spheroplast". www.merriam-webster.com. Merriam-Webster. 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ Thorpe TA (October 2007). "History of plant tissue culture". Molecular Biotechnology. 37 (2): 169–180. doi:10.1007/s12033-007-0031-3. PMID 17914178. S2CID 25641573.

- ^ Sandgrind S, Li X, Ivarson E, Ahlman A, Zhu LH (16 November 2021). "Establishment of an Efficient Protoplast Regeneration and Transfection Protocol for Field Cress (Lepidium campestre)". Frontiers in Genome Editing. 3 757540. doi:10.3389/fgeed.2021.757540. PMC 8635052. PMID 34870274.

- ^ Li X, Sandgrind S, Moss O, Guan R, Ivarson E, Wang ES, et al. (2021-07-07). "Efficient Protoplast Regeneration Protocol and CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Editing of Glucosinolate Transporter (GTR) Genes in Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.)". Frontiers in Plant Science. 12 680859. Bibcode:2021FrPS...1280859L. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.680859. PMC 8294089. PMID 34305978.

- ^ Bhatla SC, Kiessling J, Reski R (2002): Observation of polarity induction by cytochemical localization of phenylalkylamine-binding receptors in regenerating protoplasts of the moss Physcomitrella patens. Protoplasma 219, 99–105.

- ^ Hain R, Stabel P, Czernilofsky AP, Steinbiß HH, Herrera-Estrella L, Schell J (May 1985). "Uptake, integration, expression and genetic transmission of a selectable chimaeric gene by plant protoplasts". Molecular and General Genetics MGG. 199 (2): 161–168. doi:10.1007/BF00330254.