Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

King-in-Parliament

View on Wikipedia

In the Westminster system used in many Commonwealth realms, the King-in-Parliament (Queen-in-Parliament during the reign of a queen) is a constitutional law concept that refers to the components of parliament – the sovereign (or vice-regal representative) and the legislative houses – acting together to enact legislation.[1][2][3][4][5]

Parliamentary sovereignty is a concept in the constitutional law of Westminster systems that holds that parliament has absolute sovereignty and is supreme over all other government institutions. The King-in-Parliament as a composite body (that is, parliament) exercises this legislative authority.

Bills passed by the houses are sent to the sovereign or their representative (such as the governor-general, lieutenant-governor, or governor), for royal assent in order to enact them into law as acts of Parliament. An Act may also provide for secondary legislation, which can be made by executive officers of the Crown such as through an order in council.[6][7]

Fusion of powers

[edit]The concept of the Crown as a part of parliament is related to the idea of the fusion of powers, meaning that the executive branch and legislative branch of government are fused together. This is a key concept of the Westminster system of government, developed in England and used in countries in the Commonwealth of Nations and beyond. It is in contradistinction to the idea of the separation of powers.

In Commonwealth realms that are federations, the concept of the King in parliament applies within that specific parliament only, as each sub-national parliament is considered separate and distinct from each other and from the federal parliaments (such as Australian states or the Canadian provinces).

United Kingdom

[edit]

According to constitutional scholar A.V. Dicey, "Parliament means, in the mouth of a lawyer (though the word has often a different sense in ordinary conversation), the King, the House of Lords, and the House of Commons; these three bodies acting together may be aptly described as the 'King in Parliament,' and constitute Parliament."[2] Legal philosopher H. L. A. Hart wrote that the Queen-in-Parliament is “considered as a single continuing legislative entity”.[8]

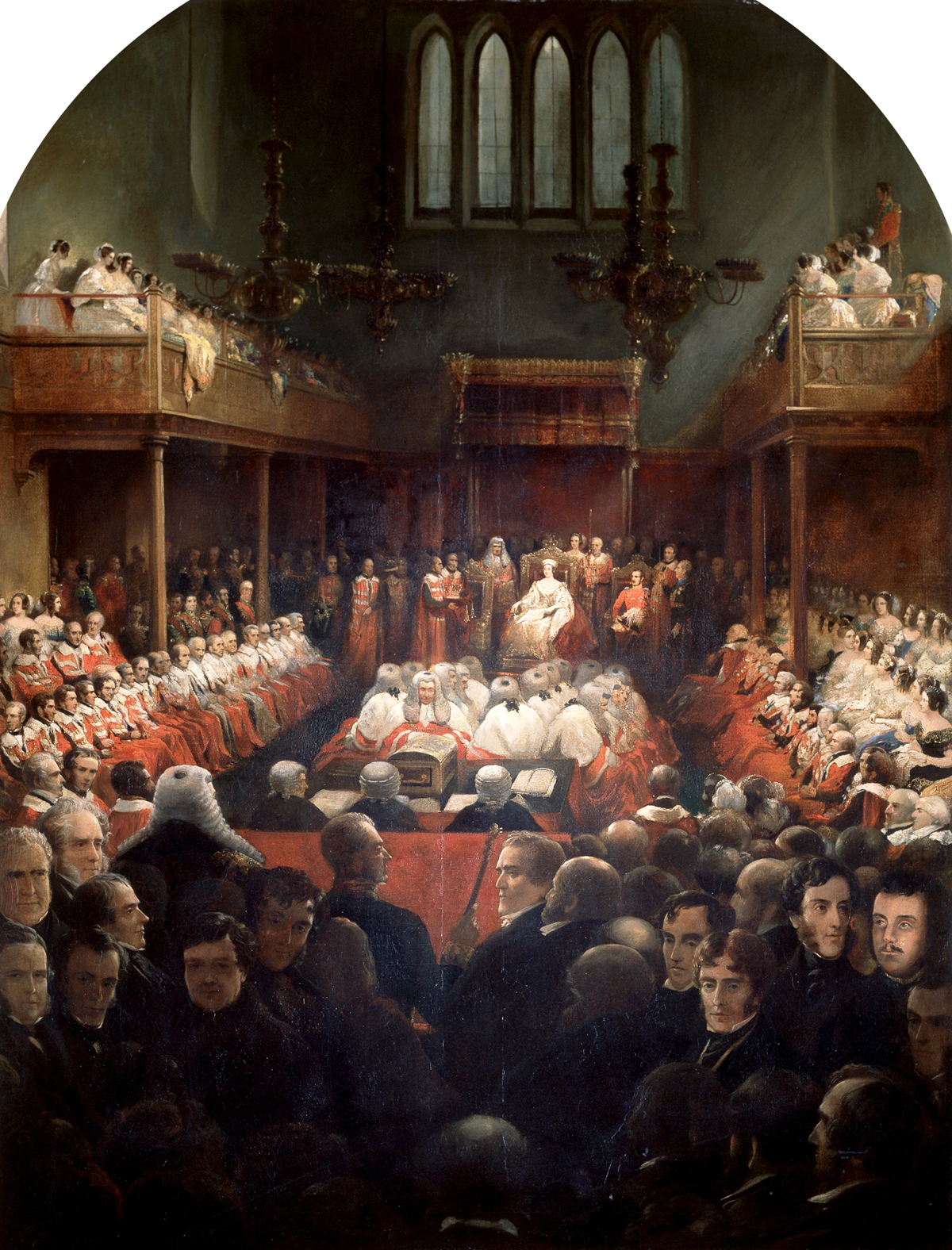

Constitutional scholar Ivor Jennings described the Queen-in-Parliament as "a purely formal body consisting of the Queen sitting on her Throne with the Lords of Parliament sitting before her and the Commons standing at the Bar."[1] This formal gathering was historically the only process by which legislation could be enacted. The Royal Assent by Commission Act 1541 allowed Lords Commissioners to stand in for the monarch, and the Royal Assent Act 1967 allowed legislation to be enacted by pronunciation, without a physical gathering. The assembling of the King, Lords, and Commons as the King-in-Parliament is now "notional rather than real",[9] only occurring ceremonially at the annual State Opening of Parliament.[1][10]

The composition of the King-in-Parliament is reflected in the enacting clause of acts of the British Parliament with: "Be it enacted by the King's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows...".

Development of parliamentary sovereignty

[edit]

In England, by the mid-16th century, it was established that the "King in Parliament" held supreme legislative authority.[12] However, this phrase was subject to two competing theories of interpretation.[12][13][14] The Royalist view interpreted the phrase as "King, in Parliament"; that is, the King acting with the consent of the Lords and Commons, but ultimately exercising his own sovereign authority.[13] The Parliamentarian view was that legislative authority was exercised by the "King-in-Parliament”, a composite institution of the King, Lords, and Commons acting together.[13]

As described by Jeffrey Goldsworthy, "The question that divided them was whether [the] final, unchallengeable decision-maker was the king alone, or the King, Lords, and Commons in parliament."[12] The dispute had implications for the ability of Parliament to limit the monarch’s powers, or "the supremacy of the King in Parliament over the King out of Parliament."[15] The clash between the Royalist and Parliamentarian views continued through the 16th century and much of the 17th, and was a factor in the English Civil War (1642-1651) and the execution of Charles I (1649).[13][16]

The Parliamentarian position ultimately prevailed with the Glorious Revolution (1688–89) and subsequent passing of the Bill of Rights 1689, which significantly limited the day-to-day powers of the monarch, including removing prerogative powers to unilaterally suspend or dispense with statutes.[17]

Balance of power within the King-in-Parliament

[edit]

The concept of the King-in-Parliament holding supreme legislative authority is a core tenet of the Constitution of the United Kingdom and has application in the Westminster system more generally.[18] As a concept, legislative authority being exercised by the King-in-Parliament is compatible with different distributions of power among its three components.[12][19] This allowed for increasing limitations on the monarch’s direct and unilateral influence within Parliament over the 18th and 19th centuries.[20] The influence of the House of Lords has also been significantly limited, most notably by the Parliament Acts 1911 and 1949, which allow money bills to be passed against the wishes of the House of Lords. Such legislation can still be understood in a constitutional sense to be an act of the King-in-Parliament, that is by the King, Lords, and Commons acting jointly as a single body known as parliament.[21]

Rules and procedures

[edit]In order to act as the King-in-Parliament, the individual components must act according to their established rules and procedures. The individuals involved must be "constituted as a public institution qua Parliament (on the basis of some rules and under certain circumstances)" in order to "[enjoy] the power to legislate as 'the [King] in Parliament' i.e., the ultimate legislature."[22] This creates a potential paradox when determining Parliament’s ability to modify its own rules or composition.[22]

Canada

[edit]

Section 17 of Canada's Constitution Act, 1867 establishes the Parliament of Canada as the legislative authority for the country, defining it as consisting of "the Queen [or King], an Upper House styled the Senate, and the House of Commons." The Parliament of Canada may be referred to as the King-in-Parliament,[4] and its three-part composition is based on "the British model of legislative sovereignty vesting in the [King]-in-Parliament".[23] Canadian acts of Parliament use the enacting clause: "Now, therefore, His Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate and House of Commons of Canada, enacts as follows..."

Canada's provincial legislatures are constitutionally defined as consisting of the province's lieutenant governor (as the representative of the King) and a popularly elected legislative assembly. The concept of King-in-Parliament also applies to these sub-national legislatures.[4]

Legal scholar Paul McHugh describes Canada as having "a crisis of constitutional identity" in the later 20th century, finding "the old Whig narrative of an absolute sovereign self (the Crown in Parliament)" to be inadequate. The Canadian response was to "not seek to refurbish a historical order so much as to fundamentally reorder it by adopting the Charter of Rights and Freedoms limiting the power of government, the Crown in Parliament (federal and provincial) included."[18]

New Zealand

[edit]The New Zealand Parliament consists of the monarch and the New Zealand House of Representatives.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Jennings, Ivor (1967). The Queen's Government. Penguin. pp. 66–68.

- ^ a b Dicey, A.V. (1915). Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution (8th ed.). London: Macmillan. p. 3.

- ^ House of Commons Library. "Chapter 5: The King in Parliament" (PDF). p. 32.

- ^ a b c A Crown of Maples (PDF). Government of Canada. 2015. p. XVII. ISBN 978-1-100-20079-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ "Definition of KING-IN-PARLIAMENT". Merriam-Webster. 23 October 2023. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ "Guide to Making Federal Acts and Regulations". www.canada.ca. Privy Council Office, Government of Canada. 13 December 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ "Meetings & Orders". Privy Council. Archived from the original on 9 May 2024. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ Hart, H.L.A. (1972). The Concept of Law. Clarendon law series. Clarendon Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-19-876072-6. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ Brazier, R. (1998). Constitutional Reform. Oxford University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-19-876524-0. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ Adonis, A. (1993). Parliament Today. Politics today. Manchester University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-7190-3978-2. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ "The Wriothesley Garter book". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d Goldsworthy, J.D. (2000). "Chapter 2: The Development of Parliamentary Sovereignty". In Dickinson, H.T.; Lynch, M. (eds.). The Challenge to Westminster: Sovereignty, Devolution and Independence. Tuckwell. pp. 12–21. ISBN 978-1-86232-152-6.

- ^ a b c d Goldsworthy, J.D. (1999). The Sovereignty of Parliament: History and Philosophy. Clarendon Press. pp. 9, 53, 65–69. ISBN 978-0-19-826893-2. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ Edlin, Douglas E. (2002). "Rule Britannia". University of Toronto Law Journal. 52 (Summer, 2002): 313. doi:10.2307/825998. JSTOR 825998.

- ^ Phillips, O.H.; Jackson, P. (1987). Constitutional and Administrative Law. Sweet & Maxwell. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-421-35030-4.

- ^ Davis, Louis B.Z. "Review of the Fundamentals: The Source of the Government's Authority and the Justification of Its Power, in Terms of Constitutional Morality". Journal of Parliamentary and Political Law. 8 (August, 2014): 489.

- ^ Horsman, Karen; Morley, Gareth (2023). "§ 1:3. The Development of the English/British Monarchy". Government Liability: Law and Practice. Thomson Reuters.

- ^ a b McHugh, P.G. (2002). "Tales of Constitutional Origin and Crown Sovereignty in New Zealand". University of Toronto Law Journal. 52 (Winter, 2002): 69. doi:10.2307/825928. JSTOR 825928.

- ^ Fenwick, H.; Phillipson, G.; Williams, A. (2020). Text, Cases and Materials on Public Law and Human Rights. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-135-07133-2. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ Rowe, Malcolm. "The History of Administrative Law". Canadian Journal of Administrative Law and Practice. 34 (March, 2021): 87.

- ^ Ekins, Richard; Gee, Graham (2022). "Ten Myths about Parliamentary Sovereignty". In Horne, A.; Thompson, L.; Yong, B. (eds.). Parliament and the Law. Hart Studies in Constitutional Law. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 299. ISBN 978-1-5099-3411-9. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ a b Eleftheriadis, Pavlos (2009). "Parliamentary Sovereignty and the Constitution". Canadian Journal of Law and Jurisprudence. 22 (July, 2009): 267. doi:10.1017/S0841820900004690.

- ^ Newman, Warren J. "Some Observations on the Queen, the Crown, the Constitution, and the Courts" (PDF). Centre for Constitutional Studies. Retrieved 6 April 2024.