Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

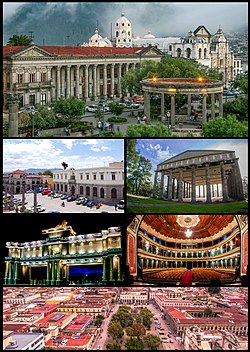

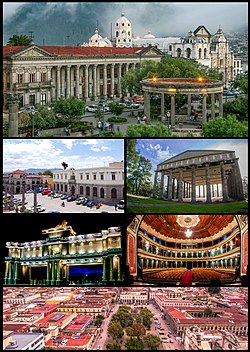

Quetzaltenango

View on Wikipedia

Quetzaltenango (Spanish pronunciation: [keˌtsal.teˈnaŋ.ɡo], also known by its Maya name Xelajú [ʃelaˈχu] or Xela [ˈʃela]) is a municipality and namesake department in western Guatemala. The city is located in a mountain valley at an elevation of 2,330 meters (7,640 feet) above sea level at its lowest part. Inside the city, it can reach above 2,400 m (7,900 ft).

Key Information

Quetzaltenango is a part of the Los Altos Metropolitan Area, which also includes the municipalities of Salcajá, Cantel, Almolonga, Zunil, Concepción Chiquirichapa, San Mateo, La Esperanza, San Juan Ostuncalco, Olintepeque, San Miguel Sigüilá, and Cajolá in Quetzaltenango Department, as well as San Cristóbal Totonicapán and San Andrés Xecul in Totonicapán Department.

As of the 2018 census, the city has a population of 180,706 in 122 km2 (47 sq mi). 43% of the population was indigenous in 2014.[3]

Etymology

[edit]The word "Quetzaltenango" is generally considered to mean "the place of the quetzal bird." The resplendent quetzal is the national bird of Guatemala, and the Guatemalan quetzal is the currency of Guatemala. Quetzaltenango became the city's official name in colonial times[citation needed].

Many people, especially the indigenous population and locals, refer to the city by its Kʼicheʼ Mayan name, "Xelajú", or more commonly "Xela". This name is derived from the indigenous xe laju' noj, meaning "under ten mountains", referring to the mountain range of the Sierra Madre de Chiapas near the city. Some proudly but unofficially consider it the "capital of the Mayas".[4]

History

[edit]

In pre-Columbian times, Quetzaltenango was a city of the Mam Mayans, although by the time of the Spanish conquest in 1524, it had become part of the K'iche' Kingdom of Q'umarkaj.[citation needed] The city was said to have already been over 300 years old when the Spanish first arrived. With the help of his allies, Conquistador Pedro de Alvarado defeated and killed the Maya ruler Tecún Umán here[citation needed].

From 1838 to 1840 Quetzaltenango was the capital of the state of Los Altos, one of the states or provinces of the Federal Republic of Central America. As the union broke up, the army of Rafael Carrera conquered Quetzaltenango making it part of Guatemala. In 1850, the city had a population of approximately 20,000.[5]

During the 19th century, coffee was introduced as a major crop in the area. As a result, the economy of Xela prospered[citation needed]. Much fine Belle Époque architecture can still be found in the city.[citation needed]

On October 24, 1902, at 5:00 pm, the Santa María Volcano erupted. Rocks and ash fell on Quetzaltenango at 6 PM, only one hour after the eruption.[citation needed]

In the 1920s, a young Romani woman named Vanushka Cardena Barajas died and was buried in the Xela city cemetery. An active legend has developed around her tomb that says those who bring flowers or write a request on her tomb will be reunited with their former romantic partners. The Guatemalan songwriter Alvaro Aguilar wrote a song based on this legend.[citation needed]

In 1930 the only electric railway in Guatemala, the Ferrocarril de Los Altos, was inaugurated. It was built by AEG and Krupp and had 14 train cars. The track connected Quetzaltenango with San Felipe, Retalhuleu. It was soon destroyed by mudslides and finally demolished in 1933. The people of Quetzaltenango are still very proud of the railway. A railway museum has been established in the city center.[citation needed]

Since the late 1990s Quetzaltenango has been having an economic boom, which makes it the city with the second-highest contribution to the Guatemalan economy[citation needed]. With its first high-rise buildings being built, it is expected by 2015[needs update] to have a more prominent skyline, with buildings up to 15 floors tall.

In 2008, the Central American Congress PARLACEN announced that every September 15, Quetzaltenango will be Central America's capital of culture.[6]

Quetzaltenango was supposed to host 2018 Central American and Caribbean Games but dropped out due to a lack of funding for the event.[7]

In March 2022, indigenous activists began blockading the central waste deposit near Valle de Palajunoj to protest a city development plan enacted by the municipal authorities in June 2017.[8]

Climate

[edit]

According to Köppen climate classification, Quetzaltenango features a subtropical highland climate (Cwb). In general, the climate in Quetzaltenango can go from mild to chilly, with occasional sporadic warm episodes. The daily high is usually reached around noon. From then on, temperatures decrease exceptionally fast. The city is quite dry, except during the rainy season. Quetzaltenango is the coolest major city in Guatemala.

There are two main seasons in Quetzaltenango (as in all of Guatemala); the rainy season, which generally runs from late May through late October, and the dry season, which runs from early November until April. During the rainy season, rain falls consistently, usually in the afternoons, but there are occasions in which it rains all day long or at least during the morning. During the dry season, the city frequently will not receive a single drop of rain for months on end.

The coldest months are November through February, with minimum temperatures averaging 4 °C or 39.2 °F, and maximum temperatures averaging 22 °C or 71.6 °F. The warmest months are March through July, with minimum temperatures averaging 8 °C or 46.4 °F and maximum temperatures averaging 23 °C or 73.4 °F. Yearly, the average low is 6.4 °C or 43.5 °F and the average high is 22.5 °C or 72.5 °F.

| Climate data for Quetzaltenango - Labor Ovalle Weather Station (Temp.: 1991−2010 / Prec.: 1980−2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 28.4 (83.1) |

29.8 (85.6) |

30.0 (86.0) |

28.2 (82.8) |

30.2 (86.4) |

26.5 (79.7) |

25.2 (77.4) |

25.0 (77.0) |

26.0 (78.8) |

25.2 (77.4) |

25.6 (78.1) |

26.2 (79.2) |

30.2 (86.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 22.0 (71.6) |

23.5 (74.3) |

25.5 (77.9) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.1 (73.6) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.9 (71.4) |

22.1 (71.8) |

20.9 (69.6) |

21.7 (71.1) |

21.3 (70.3) |

22.1 (71.8) |

22.5 (72.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.9 (55.2) |

13.7 (56.7) |

14.8 (58.6) |

15.8 (60.4) |

15.8 (60.4) |

15.6 (60.1) |

15.8 (60.4) |

15.8 (60.4) |

15.2 (59.4) |

15.0 (59.0) |

14.0 (57.2) |

13.2 (55.8) |

14.7 (58.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.3 (36.1) |

2.9 (37.2) |

3.9 (39.0) |

6.3 (43.3) |

8.8 (47.8) |

9.3 (48.7) |

8.2 (46.8) |

8.5 (47.3) |

9.0 (48.2) |

8.4 (47.1) |

6.0 (42.8) |

2.8 (37.0) |

6.4 (43.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −11.5 (11.3) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

0.6 (33.1) |

1.0 (33.8) |

2.5 (36.5) |

0.5 (32.9) |

1.0 (33.8) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−11.5 (11.3) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 1.8 (0.07) |

5.5 (0.22) |

14.4 (0.57) |

41.2 (1.62) |

131.6 (5.18) |

147.8 (5.82) |

98.7 (3.89) |

107.0 (4.21) |

134.7 (5.30) |

93.6 (3.69) |

18.7 (0.74) |

7.1 (0.28) |

802.1 (31.59) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 0.8 | 0.9 | 2.3 | 5.9 | 16.8 | 21.9 | 18.0 | 17.5 | 22.8 | 14.5 | 5.7 | 2.1 | 129.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 65.7 | 63.1 | 64.5 | 68.4 | 74.5 | 79.4 | 74.5 | 76.1 | 81.2 | 79.3 | 72.7 | 68.6 | 72.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 249.6 | 240.3 | 249.3 | 212.8 | 167.1 | 142.3 | 185.3 | 187.5 | 135.6 | 156.9 | 199.2 | 228.7 | 2,354.6 |

| Source: Instituto Nacional de Sismologia, Vulcanologia, Meteorologia, e Hidrologia[9] | |||||||||||||

Economy

[edit]Historically, the city produced wheat, maize, fruits, and vegetables. It also had a healthy livestock industry. Livestock was exported throughout the country and to El Salvador. As of 1850, wheat was the largest export, followed by cacao, sugar, wool and cotton.[5]

Sports

[edit]Quetzaltenango is home to the Club Xelajú MC soccer team. The team competes at Estadio Mario Camposeco which has a capacity of 13,500 and is the most successful non-capital team in the Liga Nacional de Fútbol de Guatemala.[10]

Due to the city's high altitude many athletes have prepared themselves here such as Olympic silver medalist Erick Barrondo and the 2004 Cuban volleyball team.[citation needed]

The swimming team has enjoyed success in national and international events.[citation needed]

Quetzaltenango withdrew from hosting the 2018 Central American and Caribbean Games. It planned to build a 30,000-seat stadium by 2016, as well seven new facilities for indoor sports and aquatics.[11]

Transportation

[edit]

The city has a system of micro-buses for quick and cheap movement. A micro-bus is essentially a large van stuffed with seats. Micro-buses are numbered based on the route they take (e.g., "Ruta 7"). There is no government-run mass transport system in the city. The sole public means of transport is the bus or micro-buses. Transportation to other cities is provided by bus. Bicycling is a way to get around and to travel to (and in) rural areas. Quetzaltenango Airport provides air service to the city.

Education

[edit]This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (April 2022) |

Quetzaltenango (Xela) is the center of many schools and Universities that provide Education to locals and many thousands of students from the surrounding cities and departments (states) and international students from North America and Europe, that's the reason it's a very important city for the south-west/north-west region of the Country of Guatemala, for many decades Quetzaltenango has produced distinguished Citizens through all Educational establishments, among those we can mention:

- Centro Universitario de Occidente San Carlos de Guatemala (CUNOC)

- Universidad Rafael Landivar

- Universidad Mariano Gálvez

- Universidad Mesoamericana

- Universidad de Occidente

- Universidad Galileo

People born in Quetzaltenango

[edit]- Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán (1913–1971), President of Guatemala

- Manuel Barillas (1845–1907), President of Guatemala

- Jesús Castillo (1877–1946), Musician [12]

- Ricardo Castillo (1891–1966), composer

- Manuel Estrada Cabrera (1898–1924), President of Guatemala

- Rodolfo Galeotti Torres (1912–1988), sculptor

- Alberto Fuentes Mohr (1927–1979), economist, finance minister, foreign minister, social-democratic leaders

- Comandante Rolando Morán (1929–1998), one of the guerrilla leaders in the Guatemalan Civil War

- Virginia Laparra (born 1980), lawyer

- Carlos Navarrete Cáceres (b. 1931), anthropologist and writer

- Efraín Recinos (1928–2011), engineer, architect, sculptor

- Otto René Castillo (b. 1934), poet and revolutionary

- Rodolfo Robles (1878–1939), physician and philanthropist

- Julio Serrano Echeverría (b. 1983), poet and writer[13]

- José Carlos de Gálvez y Valiente (1831, 1838, 1853), Alcalde Primero del Ayantamiento de Quetzaltenango

Consular representations

[edit]Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]Quetzaltenango is twinned with:

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Población por municipio en el año 2020". Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- ^ Citypopulation.de Population of departments and municipalities in Guatemala

- ^ CORREDOR ECONÓMICO Quetzaltenango-Huehuetenango/La Mesilla

- ^ "Quetzaltenango –Xela o Xelajú, Quetzaltenango | Lugares turísticos, Historia y Cómo Llegar". www.guatevalley.com. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ a b Baily, John (1850). Central America; Describing Each of the States of Guatemala, Honduras, Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. London: Trelawney Saunders. pp. 84–85.

- ^ "GuateLog - Historia de Quetzaltenango". Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ^ notisistema.com; Ciudad guatemalteca, candidata para Juegos Centroamericanos y del Caribe 2018.

- ^ Escobar, Gilberto (9 April 2022). "Guatemala: Ein Tag bei den Blockaden im Valle de Palajunoj". amerika21 (in German). Translated by Austen, Thorben. Mondial21 e. V. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ "Ministerio de comunicaciones Infraestructura y Vivienda". August 2011. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ "La historia de un grande del fútbol nacional". mixelajumc.com. Archived from the original on 14 May 2007.

- ^ noticias.emisorasunidas.com Archived 2012-03-23 at the Wayback Machine; Xela presenta candidatura para realizar Juegos Centroamericanos y del Caribe 2018. Radio Emisoras Unidas - en línea desde Guatemala.

- ^ "Jesús Castillo". HMdb.org – The Historical Marker Database.

- ^ "Julio Serrano". www.literaturaguatemalteca.org. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ "Por primera vez Consulado Móvil a la Ciudad de Quetzaltenango, llevará el Consulado General de Guatemala". Comunidad en Accion. Archived from the original on 8 November 2007. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ "Consulados de Italia en Guatemala".

- ^ "Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores | Gobierno | gob.mx". Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ "Orden AEC/2996/2007, de 1 de octubre, por la que se crea una Oficina Consular Honoraria de España en Quetzaltenango (Guatemala)". Lexur Editorial. Archived from the original on 17 June 2008. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ "Acuerdos interinstitucionales registrados por dependencias y municipios de Campeche". sre.gob.mx (in Spanish). Secretaría de relaciones exteriores. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Acuerdos interinstitucionales registrados por dependencias y municipios de Chiapas". sre.gob.mx (in Spanish). Secretaría de relaciones exteriores. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ "Sister Cities". cityoflivermore.net. City of Livermore. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ^ "Capitulaciones de Santa Fe" (PDF). santafe.es (in Spanish). Granada Hoy. April 2012. p. 7. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ "Acuerdos interinstitucionales registrados por dependencias y municipios de Oaxaca". sre.gob.mx (in Spanish). Secretaría de relaciones exteriores. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ "Reactivación económica: primer encuentro virtual Xela – Tapachula". lavozdexela.com (in Spanish). La Voz de Xela. 16 July 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ "Fakta om Tromsø: Tromsøs vennskapsbyer". tromso.kommune.no (in Norwegian). Tromsø Kommune. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ^ "Municipalidad se pronuncia sobre viaje de concejal a Turín". lavozdexela.com (in Spanish). La Voz de Xela. 14 June 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ "Acuerdos interinstitucionales registrados por dependencias y municipios de Veracruz". sre.gob.mx (in Spanish). Secretaría de relaciones exteriores. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 747.

Quetzaltenango

View on GrokipediaEtymology and Naming

Origins and Usage

The name Quetzaltenango originates from Nahuatl, the language of the Aztec allies who accompanied Spanish conquistadors during the conquest of Guatemala in the early 16th century.[3] It is interpreted as "under the wall of the quetzal," referring to the quetzal bird (Pharomachrus mocinno), a symbol of the region's highlands, or possibly alluding to abundant quetzals in the area.[5] This nomenclature was imposed around 1524 following the defeat of local Mayan forces, replacing earlier indigenous designations as part of the colonial renaming process facilitated by Nahuatl-speaking auxiliaries from central Mexico.[6] Prior to Spanish arrival, the settlement was known among Mayan peoples—primarily Mam and later K'iche' speakers—as Xelajú, derived from the K'iche' phrase xe laju' noj, meaning "under ten mountains," in reference to the encircling Sierra Madre de Chiapas peaks.[7] Earlier Mam inhabitants may have called it Q'ulaja or Culajá, signifying "gorge" in their language, reflecting the local topography of valleys and ravines.[5] These pre-colonial names persisted in oral traditions despite the official adoption of Quetzaltenango during the colonial era. In contemporary usage, Quetzaltenango remains the formal name for the city and department, as designated in Guatemalan administrative records and official documents.[8] However, Xela—a phonetic abbreviation of Xelajú—predominates in everyday speech among residents and in local media, underscoring cultural reclamation of indigenous heritage.[9] This dual nomenclature highlights the city's layered identity, with Xela evoking Mayan roots while Quetzaltenango evokes colonial imposition, though the latter is retained for legal and international contexts.[10]Geography

Location and Topography

Quetzaltenango serves as the capital of the Quetzaltenango Department in the western highlands of Guatemala, positioned approximately 206 kilometers northwest of Guatemala City.[11] The city occupies a mountain valley within this highland region, characterized by its elevated and rugged terrain.[8] Geographically, Quetzaltenango is situated at coordinates 14°50′02″N 91°31′09″W.[12] Its central area lies at an elevation of 2,333 meters (7,654 feet) above sea level, with variations reaching up to 2,400 meters in higher parts of the urban zone.[13][14] This high-altitude positioning places it amid a topography of steep slopes, volcanic influences, and fertile intermontane basins conducive to agriculture.[15] The surrounding landscape includes prominent volcanic features and mountain ranges that define the local relief, with elevations in the broader department averaging around 2,333 meters but descending toward coastal lowlands in adjacent areas.[16] These topographic elements contribute to a diverse micro-relief, featuring valleys, ridges, and escarpments that shape settlement patterns and land use.[17]Climate and Environmental Features

Quetzaltenango features a subtropical highland climate with mild temperatures throughout the year, averaging 14.8 °C (58.6 °F) annually. Daily highs typically reach 22–24 °C (72–75 °F), while lows range from 10–12 °C (50–54 °F), influenced by its elevation of approximately 2,330 meters above sea level. The dry season spans November to April, with mostly clear skies, while the wet season from May to October brings frequent afternoon rains.[18][19][20] Annual precipitation measures around 3,124 mm (123 inches), supporting lush vegetation but contributing to risks of landslides during heavy downpours. The climate supports diverse agriculture, including coffee, grains, and vegetables, due to the fertile soils derived from volcanic ash.[18][3] Environmentally, the region encompasses volcanic landscapes, with nearby active volcanoes such as Santa María shaping the topography and providing nutrient-rich soils. Rivers like the Samalá traverse the mountainous terrain, aiding irrigation but also posing flood hazards. The area experiences seismic activity owing to its position in a tectonically active zone, alongside features like thermal springs emerging from geothermal sources. Biodiversity includes highland forests and páramo-like ecosystems at higher altitudes, though deforestation pressures exist from agricultural expansion.[3][21]History

Pre-Columbian Period

The Quetzaltenango Valley was initially settled by the Mam Maya during the Late Preclassic period, around 200 BCE, with communities established near southern volcanoes in areas now known as Transfiguración, San Bartolomé, Zona 1, and portions of Zona 4.[5] These early inhabitants named the primary settlement Culajá or Q’ulaja, deriving from the Mam term for "gorge" and referencing a lagoon in present-day La Ciénaga, Zona 2.[5] During the Postclassic period (c. 900–1524 CE), the region became a focal point for territorial rivalries between the Mam and K'iche' Maya, exemplified by disputes over key resources like a contested spring in nearby Ostuncalco, which underscored the integration of natural features into cultural and sacred landscapes defined by the valley's ten prominent hills and volcanoes.[22] The K'iche' ultimately conquered the Mam-held areas, prompting an exodus of Mam populations and renaming the site Xe Lajuj Noj, meaning "under the ten thoughts" in K'iche' and alluding to the encircling peaks or conceptual domains.[5] [22] This conquest integrated Xelajú—a phonetic variant of the name—into the expanding K'iche' domain prior to European contact.[5] Archaeological interpretations draw on ethnohistoric records, including colonial land titles and K'iche' texts like the Popol Vuh, to highlight the valley's role in highland Maya population dynamics and landscape sacrality.[22]Spanish Conquest and Colonial Era

The Spanish conquest of the Quetzaltenango region formed part of Pedro de Alvarado's broader campaign into the Guatemalan highlands in early 1524, following his arrival from Mexico with approximately 400 Spaniards and several thousand Nahua allies. Alvarado's forces encountered fierce resistance from K'iche' Maya warriors under the command of the ajpop Tecún Umán near the plain that would become Quetzaltenango, engaging in a series of battles that included a decisive clash where Tecún Umán was killed, reportedly by Alvarado himself during hand-to-hand combat.[23] [24] These engagements, marked by Spanish cavalry charges and firearms against indigenous obsidian weapons and numerical superiority, broke K'iche' resistance in the area, allowing Alvarado to claim the territory and rename the indigenous settlement of Xelajú (meaning "under the ten hills" in K'iche') as Quetzaltenango, possibly deriving from Nahuatl references to quetzal birds or a fallen Mexica auxiliary.[25] Subsequent consolidation involved the imposition of the encomienda system, whereby Spanish encomenderos were granted authority over indigenous communities for tribute extraction in goods, labor, and gold, primarily targeting the local Mam and K'iche' populations who had sustained pre-conquest agricultural economies centered on maize, beans, and cacao. The region, integrated into the Captaincy General of Guatemala under the Audiencia Real established in 1542, functioned as a peripheral administrative district with a cabildo for Spanish settlers, though indigenous governance structures like the ayuntamiento indígena persisted under colonial oversight. Demographic impacts were severe, with warfare, enslavement, and introduced diseases such as smallpox reducing the native population by an estimated 80-90% within decades, as documented in Alvarado's own letters to the Spanish crown detailing the subjugation of highland Maya groups.[26] [27] During the colonial era, Quetzaltenango's economy shifted toward tribute-based agriculture and early hacienda production, including wheat and livestock suited to the highland climate, supporting Spanish elites and Santiago de Guatemala (modern Antigua) as the regional capital. Indigenous labor was mobilized via repartimiento mandates for public works and transport along trade routes to the Pacific coast, fostering a stratified society where Maya communities retained some communal lands but faced ongoing cultural suppression through missionary efforts by Dominicans and Franciscans starting in the 1540s. By the late 17th century, the area had stabilized as a multicultural highland node, with Spanish-style architecture emerging around the central plaza amid enduring indigenous markets, though revolts like the 1760s indigenous uprisings in nearby Totonicapán highlighted persistent tensions over tribute burdens.[28]Independence, Liberal Reforms, and 19th-Century Growth

Following Central America's declaration of independence from Spain on September 15, 1821, Quetzaltenango integrated into the Provincias Unidas del Centro de América as part of the State of Guatemala.[29] Local leaders in the city had actively supported the independence movement, reflecting its emerging role as a regional hub in the western highlands.[3] In 1822, amid Agustín de Iturbide's Mexican Empire, political authorities in Quetzaltenango swore allegiance to the emperor, though this arrangement dissolved shortly thereafter with the federation's formation.[3] As the federal republic fragmented in the late 1830s, liberal elites in Quetzaltenango sought greater autonomy from the conservative-dominated government in Guatemala City. On April 2, 1838, a secessionist assembly in the city proclaimed the independent State of Los Altos, designating Quetzaltenango as its capital and incorporating the departments of Quetzaltenango, Totonicapán, Sololá, and parts of San Marcos and Huehuetenango.[30] This short-lived entity emphasized liberal principles, including reduced clerical influence and economic liberalization, contrasting with the centralist policies from the capital; it received provisional recognition from the federal congress on June 5, 1838.[31] However, conservative forces under Rafael Carrera invaded in January 1840, capturing Quetzaltenango and dissolving Los Altos by April, reintegrating the territory into Guatemala and marking a conservative resurgence that lasted until the 1870s.[32] The period of conservative rule under Carrera prioritized rural stability and indigenous alliances, limiting urban liberal initiatives in Quetzaltenango. This shifted with the 1871 Liberal Revolution, led by Justo Rufino Barrios and Miguel García Granados, who overthrew the regime and installed Barrios as president in 1873.[33] Barrios implemented sweeping reforms, including the expropriation of church and communal lands for export agriculture, secular education, and infrastructure development such as roads linking highland areas to ports.[34] These policies accelerated coffee cultivation in Guatemala's fertile western highlands, where Quetzaltenango's vicinity provided ideal volcanic soils and altitude for the crop, transforming local estates into fincas that drove export revenues.[35] By the late 19th century, coffee exports—rising from negligible shares in the 1850s to dominating Guatemala's economy—fostered Quetzaltenango's growth as a commercial and processing center, with expanded markets for wheat, grains, and livestock complementing plantation outputs.[36] The reforms spurred urban infrastructure, including neoclassical buildings and improved trade routes, positioning the city as a prosperous highland node amid national modernization efforts under Barrios until his death in 1885.[37] This era laid foundations for Quetzaltenango's demographic and economic expansion, though benefits accrued unevenly, favoring ladino elites over indigenous laborers coerced into finca work.[34]20th-Century Developments and Civil War

The early 20th century saw Quetzaltenango's economy remain anchored in coffee production, with the surrounding highlands hosting numerous export-oriented fincas that drove regional growth and urban expansion. German immigrants operated key plantations until mid-century nationalizations disrupted foreign ownership, amid Guatemala's broader export-led policies favoring coffee elites.[38][34] The 1944 October Revolution introduced social reforms, including the 1952 agrarian decree that redistributed idle lands to K'iche' Maya communities in Quetzaltenango, fostering short-term peasant gains but provoking landowner backlash and contributing to political instability.[39] The subsequent 1954 U.S.-backed coup reversed these changes, installing military governments that prioritized anti-communist security over reform, setting the stage for escalating rural tensions. Educational institutions emerged, such as the Rafael Landívar University campus established in 1963, reflecting modest intellectual development amid economic reliance on agriculture.[40] The Guatemalan Civil War (1960–1996) profoundly impacted Quetzaltenango department, where left-wing guerrilla groups, including remnants active near Cerro Lacandón volcano outside the city, sought rural support among indigenous populations.[41] Government forces responded with counterinsurgency campaigns targeting suspected collaborators, leading to documented state violence including extrajudicial killings, forced displacements, and destruction in highland villages, as quantified in human rights data from the region.[42] While urban Quetzaltenango avoided the scale of massacres seen in neighboring departments like El Quiché, the conflict exacerbated economic stagnation, with prosperity declining from wartime disruptions, infrastructure neglect, and population flight—over 200,000 Guatemalans killed or disappeared nationwide, many in Mayan areas.[43] Guerrilla actions, though fewer, included ambushes and coercion, but a UN-backed truth commission attributed 93% of atrocities to state actors versus 3% to insurgents, a finding reflecting extensive military scorched-earth tactics yet drawing critique for underemphasizing guerrilla-initiated violence.[44] The war's legacy in Quetzaltenango included heightened militarization and civic organizing, paving the way for post-1996 peace accords that enabled limited recovery.[45]Post-War Recovery and Recent Events

Following the signing of the Peace Accords on December 29, 1996, which ended Guatemala's 36-year civil war, Quetzaltenango, as a major urban center in the western highlands, contributed to and benefited from national reconstruction initiatives focused on demobilization, infrastructure rehabilitation, and economic diversification.[46] The accords emphasized indigenous rights and socioeconomic reforms, aiding recovery in regions like Quetzaltenango where Maya communities had endured displacement and violence, though implementation faced delays due to persistent inequality and weak governance.[47] Local efforts included reintegration programs for former combatants and expansion of agricultural exports, particularly coffee from surrounding highlands, supporting urban commerce in the city.[48] Economic recovery accelerated through tourism growth, with Quetzaltenango emerging as a hub for language immersion and cultural experiences, leveraging its colonial architecture and access to sites like the Santiaguito volcanic complex.[49] National tourist arrivals surged post-war, from 508,000 in 1990 to higher levels by the early 2000s, bolstering service sectors in secondary cities like Quetzaltenango despite uneven benefits for indigenous populations. Commercial development continued, exemplified by the September 2025 opening of PriceSmart's seventh Guatemalan warehouse club in the city, signaling retail expansion and consumer market maturation.[50] Recent events underscore ongoing tensions alongside progress, including territorial conflicts in the Palajunoj Valley over mining concessions, where local authorities and indigenous groups contest land use amid post-war liberalization policies favoring extractive industries.[51] These disputes reflect broader challenges in balancing economic development with community autonomy, as national impunity for war-era crimes persists, indirectly affecting regional stability.[52] Infrastructure improvements, such as rural road upgrades benefiting highland connectivity, have supported trade but remain vulnerable to fiscal constraints and environmental risks like volcanic activity.[53]Demographics

Population Trends

The population of Quetzaltenango municipality stood at approximately 144,000 inhabitants according to the 2002 national census conducted by Guatemala's Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE).[54] By the 2018 census, this figure had risen to 180,706 for the urban core of the city, reflecting sustained urban expansion within the municipality's 122 km² area. INE projections based on census data estimate the municipal population at 207,620 by 2023, implying an average annual growth rate of 1.8% between 2018 and 2023, higher than the national average of about 1.5%.[55] [1] This growth trajectory traces back to the mid-20th century, when the city's population was around 28,000 in the early 1950s, accelerating due to internal migration from rural Mayan communities in the western highlands seeking employment in agriculture, trade, and emerging industries.[56] Natural increase contributed significantly, with Guatemala's total fertility rate averaging 2.9 children per woman in the 2010s, though declining to 2.7 by 2020 amid improving access to education and health services in urban centers like Quetzaltenango. Net migration inflows, estimated at positive balances from surrounding departments, have sustained densities exceeding 1,600 inhabitants per km² in recent projections.[1]| Census Year | Population (City/Urban Core) | Annual Growth Rate (Prior Period) |

|---|---|---|

| 2002 | ~144,000 (municipality) | ~2.0% (from 1990s estimates) |

| 2018 | 180,706 | ~1.6% (2002-2018 average) |

Ethnic and Linguistic Composition

Quetzaltenango's ethnic composition reflects Guatemala's broader demographic patterns but with a higher proportion of indigenous residents compared to the national average. According to data from the 2018 national census, the municipality's population includes 84,326 individuals identifying as Maya, comprising approximately 58% of the total, primarily from the Mam and K'iche' subgroups.[1] Ladinos (those of mixed European and indigenous ancestry, culturally aligned with Spanish-speaking mestizos) form the next largest group at around 41%, with negligible numbers of Xinca (86 individuals) and Garifuna (209).[1] In the surrounding department, indigenous proportions rise to about 61-65%, driven by rural Mam communities, though urban areas like the city center show greater Ladino dominance due to historical migration and assimilation trends.[58][59] Linguistically, Spanish serves as the lingua franca and official language, spoken by over 90% of residents, reflecting national patterns where it dominates urban commerce, education, and administration.[60] Among the indigenous majority, Mayan languages predominate: Mam is the primary tongue in rural outskirts and surrounding municipalities, while K'iche' prevails in the city proper and nearby highlands.[61] These languages correspond directly to ethnic affiliations, with bilingualism common among younger Maya speakers who acquire Spanish through schooling, though full indigenous language retention is higher in rural zones—estimated at around 40% of the departmental population speaking a Mayan language as of early 2000s surveys, a figure likely stable given persistent cultural practices.[62] Smaller pockets of other Mayan dialects exist due to migration, but non-Maya indigenous languages like Xinca or Garifuna have minimal presence.[1]Economy

Agricultural Base and Exports

The agricultural sector forms the foundation of Quetzaltenango's economy, leveraging the department's highland terrain and volcanic soils for diverse crop cultivation. Principal staples include maize, beans, and wheat, with the latter accounting for 16% of Guatemala's total wheat production as of 2023. Cash crops such as coffee thrive in lower-altitude areas like Colomba and Costa Cuca, where farms produce varieties including Bourbon, Caturra, Catuai, and Pacamara at elevations around 1,600 meters.[63][64] Vegetable production is prominent, particularly in municipalities like Almolonga, renowned for high-yield, oversized horticultural crops such as cabbage, carrots, radishes, onions, and potatoes, attributed to fertile soils enriched by geothermal activity and intensive farming practices. These vegetables support both local consumption and regional markets, with producers cultivating tomatoes, peppers, and other items for self-sufficiency and sale. Livestock rearing, including cattle and horses, complements crop farming in areas like Coatepeque.[65][66] Exports from Quetzaltenango's agricultural base are dominated by coffee, which contributes to Guatemala's national output of specialty beans destined for international markets, emphasizing the department's role in the country's $4.4 billion agricultural export total in 2023. While vegetables primarily serve domestic and Central American trade, coffee's high-density, acidity-rich profile from highland farms bolsters foreign earnings, with organizations like the Federación Comercializadora de Café Especial de Guatemala facilitating small-producer sales since 2006.[67][68]Industry, Services, and Tourism

Quetzaltenango's manufacturing sector, concentrated in the department's urban areas, includes food processing for products like wheat and corn flour used in baking and tortillas, as well as chocolate production.[69] Textile and apparel manufacturing, such as garment factories like Industrias Italtex, also contribute, supporting export-oriented activities alongside food processing.[70] [71] These industries reflect the city's historical development as a production center since the 19th century, leveraging local agriculture for raw materials.[72] The services sector dominates the local economy, encompassing commerce through major markets like the Cuatro Caminos junction, which facilitates trade in goods from surrounding highlands.[73] Education services are prominent, with Quetzaltenango hosting numerous language schools and universities that attract both local and international students, fostering a vibrant student economy. Financial and logistical services, including banking and export logistics, support regional trade, positioning the city as a western Guatemala hub.[74] Tourism in Quetzaltenango emphasizes adventure and cultural experiences, drawing visitors to natural sites such as Laguna Chicabal for hiking and spiritual retreats, Fuentes Georginas hot springs for thermal bathing, and Cerro Quemado for panoramic views.[75] Volcanic attractions like Santa María Volcano and Santiaguito offer guided climbs and observation tours, appealing to eco-tourists and backpackers.[76] The city's central park and historic buildings provide urban exploration, while Spanish immersion programs enhance its appeal as a base for highland travels; the INGUAT tourist office assists with information on these offerings.[77] Though specific visitor statistics for the city are limited, its role in Guatemala's tourism growth—national arrivals reached over 3 million in 2024—underscores its contribution to services revenue.[78]Economic Challenges and Development Issues

Despite its relative economic advantages compared to more impoverished eastern departments, Quetzaltenango grapples with a multidimensional poverty rate of approximately 44% in 2023, driven by rural-urban disparities and heavy reliance on informal agriculture and remittances, which exacerbate vulnerability to external shocks.[79] [80] The department's economy, dominated by services and commerce in the urban center of Xela, contrasts with subsistence farming in highland municipalities, where indigenous populations face chronic underinvestment in education and health, perpetuating cycles of low human capital and limited productivity gains.[75] Labor market challenges include widespread informality, estimated nationally at over 70% but similarly prevalent locally, leading to subemployment, lack of social protections, and stagnant wages that hinder formal sector growth.[81] [82] High emigration rates to the United States fuel remittances—second only to the capital in regional inflows—but contribute to labor shortages in agriculture and dependency on volatile transfers, which, while stabilizing household incomes, distort local investment and inflate living costs without fostering sustainable diversification.[83] [84] Development is further impeded by infrastructure deficits and exposure to natural disasters, including earthquakes and volcanic activity in the seismic highlands, which disrupt agricultural exports like coffee and maize while straining limited public resources for reconstruction.[2] Territorial disputes over mining in areas like the Palajunoj Valley add friction, pitting local communities against extractive interests amid weak governance and corruption that undermine equitable resource allocation.[51] Climate variability intensifies these issues, with droughts and frosts reducing yields and accelerating out-migration, underscoring the need for resilient infrastructure and policy reforms to transition from remittance reliance to productive investment.[85]Government and Administration

Local Governance Structure

The municipal government of Quetzaltenango operates as an autonomous entity under Guatemala's Municipal Code (Decree 12-2002), which grants it political, fiscal, and administrative authority to manage local affairs including public services, urban planning, and taxation.[86] The core governance organs consist of the Municipal Council (Concejo Municipal) and the Mayor's Office (Alcaldía Municipal), with the former functioning as the supreme deliberative and legislative body responsible for approving budgets, enacting ordinances, and supervising executive actions.[86] [87] The Municipal Council is composed of the mayor (alcalde), trustees (síndicos), and councilors (regidores or concejales), all elected directly by popular vote for non-consecutive four-year terms as stipulated by the Municipal Code and electoral regulations.[86] The mayor presides over the Council while heading the executive branch through the Alcaldía, which handles day-to-day administration, policy implementation, public works, and representation of the municipality in external relations.[86] Trustees typically oversee specific sectors such as fiscal accountability or public advocacy, while councilors contribute to legislative deliberations.[86] Supporting bodies include the Internal Audit Unit (Unidad de Auditoría Interna), which conducts financial and operational audits to ensure compliance and transparency, and the Municipal Affairs Court (Juzgado de Asuntos Municipales), tasked with resolving administrative disputes and enforcing local regulations.[87] These elements form a hierarchical structure where the Council provides oversight, enabling checks and balances within the executive framework.[87]Political Controversies and Territorial Disputes

In 1838, amid tensions within the Federal Republic of Central America, liberal elites in Quetzaltenango declared the independent State of Los Altos on February 2, encompassing territories that included present-day departments of Quetzaltenango, San Marcos, Huehuetenango, Totonicapán, Quiché, Sololá, Retalhuleu, and Suchitepéquez, with Quetzaltenango as its capital.[88][89] This secessionist move stemmed from regional grievances over economic marginalization and political dominance by conservative forces in Guatemala City, reflecting broader ideological clashes between liberal reformers favoring autonomy and centralist conservatives.[90] The state operated briefly with its own constitution, flag, and institutions before Guatemalan forces under conservative leader Rafael Carrera invaded in 1840, dissolving Los Altos and reincorporating it into Guatemala by March of that year through military suppression.[88][89] The Los Altos episode remains a symbol of regional separatism in Quetzaltenango's history, occasionally invoked in modern discourse on local autonomy, though it has not led to renewed formal territorial claims against Guatemala.[91] No active interstate territorial disputes involve Quetzaltenango directly, as Guatemala's national border issues, such as the Belizean–Guatemalan dispute, pertain to eastern frontiers unrelated to the western highlands.[92] In contemporary times, political controversies in Quetzaltenango center on local territorial ordering and resource conflicts, particularly in the Palajunoj Valley, where indigenous Mam communities have contested mining concessions and state-led land titling efforts since the early 2010s.[51] These disputes involve clashes between municipal authorities, private mining interests, and indigenous groups over authority to define territorial boundaries and regulate extraction, often escalating into protests and legal challenges against perceived encroachments on communal lands.[51] Such conflicts highlight ongoing tensions in Guatemala's western highlands, where weak formal governance amplifies informal power dynamics, though they remain intra-departmental rather than inter-regional.[51] Local elections have occasionally featured accusations of corruption tied to these issues, but no systemic territorial secessionism has emerged post-1840.[93]Culture and Society

Indigenous Heritage and Traditions

The indigenous heritage of Quetzaltenango centers on the Mam Maya, one of Guatemala's 22 Maya ethnic groups, whose presence in the western highlands dates to approximately 2500 B.C., predating Spanish colonization and forming the core of local pre-Columbian settlement around volcanic bases in the valley. Mam communities, such as those in Cabricán (population around 25,000) and Cajolá within the Quetzaltenango department, maintain ancestral ties to the land through practices emphasizing harmony with nature, consensus-based decision-making, and elder respect, reflecting a cosmovision that integrates earthly and cosmic elements.[94][95][94] Key traditions include the preservation of the Mam language as the primary tongue in rural communities, alongside syncretic spiritual practices blending Maya rituals with Catholicism, such as ceremonies at sacred sites like Lake Chicabal, a volcanic crater lake where Mam perform offerings during Ascension Day on May 9 or 40 days post-Easter to invoke rain and fertility. Music features prominently, with the marimba—an instrument adapted from pre-Hispanic origins and documented in use since the 17th century—accompanying communal events and reinforcing cultural continuity. Community defense of territory, exemplified by consultations in seven of eight Mam municipalities rejecting mining projects like Goldcorp's ELUVIA initiative, underscores ongoing efforts to safeguard heritage against external pressures.[94][96][94][95] Crafts, particularly backstrap weaving—a technique over 2,000 years old passed matrilineally—produce intricate traje (traditional attire) like colorful huipiles and skirts, visible in urban markets such as Mercado Minerva and supported by cooperatives including Trama Textiles (empowering over 150 Maya women) and Tejedoras Maya Mam in Cajolá, which market handwoven goods to sustain families and resist cultural erosion from migration and poverty. Festivals like the Festival de la Cultura Mam highlight these elements through dance, music, and artisanal displays, fostering intergenerational transmission amid broader Maya influences from groups like K'iche' in the region.[97][98][100]Festivals, Arts, and Daily Life

Quetzaltenango hosts the Feria Centroamericana de la Independencia, commonly known as Xelafer, annually in September to mark Central American independence from Spain. This event, originating in the late 19th century, features parades with thousands of participants, including schoolchildren marching on September 10, free concerts, bazaars, and cultural exhibitions centered in Parque Benito Juárez.[101][102][103] The 141st edition in 2025 drew large crowds for its blend of patriotic displays and local traditions.[104] Other notable celebrations include All Saints' Day on November 1, observed with family visits to cemeteries and offerings that integrate Catholic rituals with indigenous practices.[96] The city's arts scene revolves around institutions like the Teatro Municipal, a neoclassical venue with a capacity of 1,000 that hosts theatrical performances, concerts, and community events.[105] The Museo de Arte functions as an exhibition space for Guatemalan painters and sculptors while serving as a cultural hub for lectures and film screenings.[106] Local music thrives through diverse genres, supported by venues and festivals that highlight both traditional marimba and contemporary sounds.[107] Daily life in Quetzaltenango reflects a fusion of urban energy and highland traditions, with residents frequenting bustling markets for fresh produce, textiles, and crafts woven on backstrap looms.[97] The city supports a vibrant community of students, artists, and artisans who preserve Mayan customs amid concrete architecture and cool mountain air.[108] Social interactions often center on family-oriented routines, street vendors, and evening gatherings in central parks, punctuated by the sounds of marimba and everyday commerce.[109]Social Issues Including Migration Drivers

Poverty remains a persistent challenge in Quetzaltenango, with rural areas exhibiting rates as high as 93.8 percent, contrasting with the department's overall poverty rate of approximately 33.3 percent, which is lower than the national average of around 47 percent as of recent estimates.[110][111][112] This disparity underscores urban-rural divides, where indigenous Mam and other Maya communities in surrounding highlands face limited access to land, soil degradation, and agricultural stressors exacerbated by climate variability, contributing to chronic underemployment and food insecurity.[113][114] Crime and violence further compound social strains, including gang-related homicides, extortion rackets targeting entrepreneurs, and vigilante lynchings that have supplanted formal state authority in parts of the city.[115][116] Theft, assaults, and drug trafficking incidents are reported, though less severe than in Guatemala's eastern departments, with prison facilities like the local women's center exemplifying overcrowding, inadequate sanitation, and prisoner-on-prisoner violence.[117][118][119] Territorial disputes over mining and land use in valleys like Palajunoj add tensions, often pitting local indigenous groups against external interests.[51] These factors drive significant out-migration, primarily to the United States, where economic desperation—cited by about 90 percent of Guatemalan emigrants—stems from insufficient job opportunities, low wages, and rural poverty rather than solely violence.[120][121] In Quetzaltenango's context, family units from high-poverty rural zones migrate due to agricultural failures linked to environmental degradation and climate impacts, with projections estimating up to 60,000 potential climate-displaced residents under pessimistic scenarios.[114][122] Extortion and business losses force entrepreneurs to flee as refugees, while remittances—97 percent from the U.S.—sustain households but fail to reverse outflows, as net migration remains negative at around -8,000 annually nationwide.[116][123][124] Internal migration to the capital also occurs from rural Quetzaltenango, reflecting broader patterns of seeking urban employment amid inequality.[110]Infrastructure and Services

Transportation Networks

Quetzaltenango is primarily connected to the rest of Guatemala by road networks, with the CA-1 Inter-American Highway serving as the main artery linking it to Guatemala City approximately 200 kilometers to the east.[125] The route passes through the highlands, including a turnoff at Cuatro Caminos, a major interchange facilitating connections to other western regions.[126] Bus travel predominates, with companies such as Transportes Starbus operating regular services from Guatemala City, covering the distance in about 4 to 6 hours depending on traffic and vehicle type.[127] Private shuttle minibuses, favored by tourists for safety, follow similar routes but may include stops, extending travel time.[128] Public transportation within and around Quetzaltenango relies on informal bus systems known as camionetas or chicken buses, which operate on fixed routes but lack formal schedules, supplemented by microbuses and taxis for shorter distances.[129] The CA-1 extends westward toward the Mexican border at La Mesilla, enabling overland travel, though road conditions include frequent speed bumps and variable maintenance.[130] No passenger rail services connect the city, as Guatemala's rail network is limited and non-operational for public use.[131] Air access is provided by Quetzaltenango Airport (IATA: AAZ), a small domestic facility located near the city that handles limited flights, primarily to Guatemala City.[132] Recent renovations to its facade and signage were completed in August 2025 to improve infrastructure.[133] Plans announced in March 2025 aim to introduce select international routes to Central America and Mexico by December 2026, potentially expanding connectivity.[134] However, most regional air travel currently routes through Guatemala City's La Aurora International Airport.[135]Education System

The education system in Quetzaltenango follows Guatemala's national structure, which includes pre-primary education (ages 4-6), primary education (six years), basic education (three years), and diversified secondary education (two to three years), culminating in higher education opportunities. Primary school enrollment in the Quetzaltenango department stands at approximately 95.6%, exceeding national averages and reflecting relatively strong access in urban areas like the city itself.[136] However, adult literacy rates in the department remain gendered, with 88% of males and 79% of females aged 15 and over literate as of 2022, influenced by persistent rural-urban disparities and socioeconomic factors.[37] Quetzaltenango functions as a regional educational hub in western Guatemala, hosting multiple institutions of higher learning. The University of San Carlos de Guatemala's University Center of the West (CUNOC), established in 1970, provides undergraduate and graduate programs in fields such as medicine, engineering, and social sciences, serving students from surrounding highland areas.[137] The Universidad Mariano Gálvez de Guatemala operates a dedicated campus in the city with 63 modern classrooms and 28 active degree programs, including law, business, and education, drawing on over five decades of institutional experience.[138] Additional options include the Mesoamerican University branch, focused on professional training in areas like marketing and computer science, and the University of the West, which emphasizes philosophy and liberty-oriented curricula.[139][140] Private and international schools, such as the International American School (IAS Xela), offer English-immersion and bilingual programs catering to expatriate and local families seeking alternatives to public systems.[141] Despite these assets, educational challenges in Quetzaltenango mirror national issues, including low instructional quality, high dropout rates beyond primary levels, and inadequate infrastructure in rural zones. The predominance of indigenous groups, such as the Mam Maya who speak non-Spanish languages, exacerbates barriers, as the system predominantly instructs in Spanish despite constitutional mandates for bilingual intercultural education, leading to comprehension gaps and cultural disconnection.[142] Poverty drives absenteeism and child labor, particularly in coffee and agriculture-dependent peripheries, while teacher shortages and underfunding limit advanced skill development, contributing to human capital constraints in the local economy.[143] Community initiatives, like the El Nahual Education Center, supplement public efforts with classes in English, math, and arts for underserved children, but systemic reforms remain limited.[144]Sports and Recreation

Local Sports Culture

Soccer dominates the local sports culture in Quetzaltenango, reflecting its status as Guatemala's most popular sport and a unifying force across social classes.[145] The city's flagship team, Club Social y Deportivo Xelajú MC, founded in 1928 as Germania and renamed after evolving through phases including ADIX in the 1930s, competes in the Liga Nacional de Fútbol de Guatemala and has secured seven national titles, most recently the Apertura phase in 2024.[146] Matches at Estadio Mario Camposeco, with a capacity of 13,500, serve as major community events, fostering passionate fan support and contributing to the city's cultural identity.[147] Basketball enjoys growing grassroots participation, particularly through informal pickup games and recreational leagues in urban areas, though it trails soccer in prominence.[148] Youth academies and clubs like Spirit F.C. and Profutbol Xela emphasize soccer development, offering structured training that channels local talent into competitive pathways.[149] Emerging facilities such as Break Point Xela promote racket sports like tennis and pickleball, attracting families and providing alternatives amid the highland terrain's suitability for endurance activities.[150] Quetzaltenango's role in regional events underscores its sports infrastructure, hosting athletics competitions for the XII Juegos Centroamericanos in 2025 at the Complejo Deportivo, which highlights investments in tracks and fields despite challenges in talent retention and funding.[151] Public spaces like Bicentennial Parks and the Intercultural Park integrate sports with recreation, encouraging community engagement in activities from jogging to team sports, though access varies by socioeconomic factors.[152][153]Major Facilities and Events

The primary sports facility in Quetzaltenango is the Estadio Mario Camposeco, a football stadium with a capacity of 11,220 seats, constructed in 1948 and serving as the home ground for Club Deportivo Xelajú MC, a professional team in Guatemala's Liga Nacional de Fútbol.[154] The venue hosts league matches, training sessions, and occasional national team events, featuring a natural grass pitch and basic athletic infrastructure without undersoil heating.[155] Additional recreational sports options include the Complejo Deportivo in Colonia Molina, which supports pickup basketball and community leagues, and Cancha Minerva for informal games.[148] Quetzaltenango hosts significant regional sports events, notably the 12th Central American Games in October 2025, where competitions in athletics, cycling, and other disciplines drew international participants from countries including Belize.[156] Local tournaments feature Xelajú MC's Liga Nacional fixtures, with the club achieving competitive success in domestic play, alongside niche events like the XELA Open Mat for martial arts on September 28, 2025, emphasizing technique and competition.[157] Basketball contests, such as women's league matches involving Quetzaltenango teams, occur at municipal courts, contributing to grassroots participation.[158] For broader recreation, Parque Centro América provides shaded areas for walking and casual sports like jogging, while Parque Municipal Cerro El Baúl offers family-oriented green spaces with trails and panoramic views, popular for picnics and light exercise among locals.[159] These sites support daily physical activity amid the city's highland terrain, though organized events remain centered on the stadium and emerging facilities like Break Point Xela for tennis and pickleball.[150]Notable Figures

Political and Cultural Leaders

Manuel Estrada Cabrera, born in Quetzaltenango on November 21, 1857, served as President of Guatemala from 1898 to 1920, establishing a long-term dictatorship characterized by economic modernization through foreign investment in railroads and agriculture, but also marked by authoritarian control via a standing army and suppression of dissent.[160] Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán, also born in Quetzaltenango on September 14, 1913, was a military officer who became president from 1951 to 1954, implementing agrarian reforms that redistributed uncultivated land from large estates to peasants, which led to United States-backed intervention and his overthrow in 1954.[161] Rigoberto Quemé Chay, an indigenous Mam leader from the region, was elected as the first Mayan mayor of Quetzaltenango in 1995, marking a significant shift in local politics by prioritizing indigenous inclusion and challenging ladino-dominated structures, which fostered greater Mayan participation in municipal governance despite ongoing ethnic tensions.[162] In the cultural sphere, Otto René Castillo, born in Quetzaltenango in 1934, emerged as a prominent poet and revolutionary intellectual who supported progressive reforms under Árbenz and later joined guerrilla movements, producing works like Let's Threaten Their Security that critiqued social inequalities; he was captured and executed by the Guatemalan regime in 1967.[163] Adrián Recinos, born in Quetzaltenango in 1886, contributed to Guatemalan cultural heritage as an archaeologist, diplomat, and translator, notably authoring Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Quiché Maya in 1947, which preserved and interpreted indigenous texts for broader scholarship.[164]Other Prominent Individuals

Rodolfo Robles Valle (January 14, 1878 – 1932) was a Guatemalan ophthalmologist and researcher born in Quetzaltenango. He earned his medical degree from the Sorbonne in Paris in 1904 after initial studies in France and returned to Guatemala to practice, establishing the country's first ophthalmology clinic in Guatemala City. Robles is credited with the first clinical description of onchocerciasis (river blindness) in 1917, identifying microfilariae in patients from the Guatemalan highlands and linking the disease to blackfly vectors, a discovery later confirmed globally and earning the condition the eponym "Robles disease."[165][166] In addition to his medical contributions, Robles engaged in philanthropy, co-founding the National Institute of Vaccination with family members and advocating for public health initiatives amid Guatemala's infectious disease burdens. His work laid foundational insights into tropical parasitology in Central America, influencing eradication efforts that reduced onchocerciasis prevalence in Guatemala from endemic levels by the mid-20th century through vector control and ivermectin distribution programs.[165]References

- https://www.[youtube](/page/YouTube).com/watch?v=l7_U0ZBRTsw