Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ratak

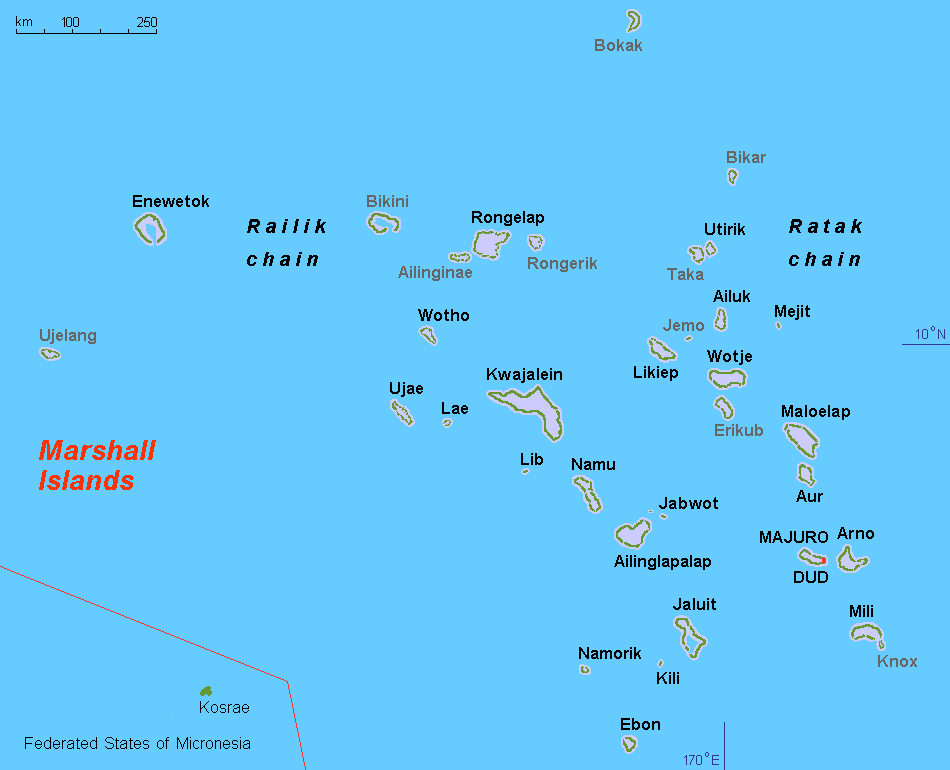

View on WikipediaThe Ratak Chain (Ratak [rˠɑːdˠɑk],[1] Marshallese for 'sunrise') is a chain of islands and atolls within the island nation of the Marshall Islands. It lies to the east of the country's other island chain, the Ralik Chain. In 1999, the total population of the Ratak islands was 30,925.[citation needed]

Key Information

The atolls and isolated islands in the chain are:

The Ratak Chain forms a continuous chain of seamounts with the Gilbert Islands to the south, which are part of Kiribati.

Language

[edit]The Ratak Chain is home to the Ratak dialect (or eastern dialect) of the Marshallese language. It is mutually intelligible with the Rālik dialect (or western dialect) located on the Rālik Chain. The two dialects differ mainly in lexicon and in certain regular phonological reflexes.

References

[edit]Ratak

View on GrokipediaGeography

Location and Physical Features

The Ratak Chain, the eastern of the two primary island chains in the Republic of the Marshall Islands, lies in the central North Pacific Ocean, centered approximately at 9°00′N 171°00′E. This northwest-southeast oriented chain extends roughly 1,100 kilometers, comprising 15 atolls and islands that form a dispersed archipelagic feature spanning from about 14°N to 4°N latitude.[5][6] Geologically, the Ratak Chain originated as a linear series of seamounts formed through intraplate volcanic activity during the Late Cretaceous period, primarily over the Rurutu hotspot, with ages ranging from 75 to 88 million years. These submerged volcanic edifices subsided over time, enabling upward coral growth and the development of atoll structures through the accumulation of reef limestones and calcareous algae, reaching elevations up to several thousand feet above the ocean floor in some cases. The chain represents the northern segment of a continuous seamount province that extends southward to connect with the Gilbert Islands in present-day Kiribati.[7][8][9][10] The Ratak Chain features a tropical maritime climate, with average annual air temperatures ranging from 27°C to 29°C and consistently high relative humidity around 80%, moderated by prevailing northeast trade winds. Annual rainfall typically measures 3,000 to 4,000 millimeters, concentrated in the southern portions due to the influence of the Intertropical Convergence Zone, though northern areas receive less. Its eastern position exposes the chain directly to moisture-laden trade winds, resulting in higher precipitation compared to the leeward western Ralik Chain. The low-lying coral landforms are particularly susceptible to tropical cyclones, which occur occasionally from May to November, and ongoing sea-level rise, observed at approximately 3.3 mm per year (1968-2023) with projections averaging 5-6 mm per year through 2050, exacerbating erosion and inundation risks.[4][11][12][13][14][15]Atolls and Islands

The Ratak Chain comprises 15 atolls and several isolated islands, spanning approximately 1,200 kilometers from northwest to southeast in the eastern Marshall Islands. These formations are primarily coral atolls consisting of narrow reef rims enclosing expansive lagoons, with a total land area of about 118 km² distributed across low-lying islets rarely exceeding 3 meters in elevation. The chain's islands are built upon ancient volcanic foundations capped by carbonate sediments, resulting in diverse reef structures that support unique marine habitats.[16] Key atolls and islands in the Ratak Chain include Majuro, the largest and most populous, along with Maloelap, Likiep, Wotje, Erikub, Ailuk, Utirik, Aur, and others such as Arno, Mili, and isolated features like Mejit and Jemo. Majuro Atoll features 64 connected coral islets linked by causeways, forming a nearly continuous landmass that serves as the national capital, with a land area of 9.17 km² enclosing a 295.05 km² lagoon. Mejit stands out as a single raised coral island without a lagoon, covering 1.86 km² and rising to about 12 meters, representing one of the few elevated limestone formations in the chain. Other notable atolls include Maloelap (land 9.82 km², lagoon 972.72 km²) and Likiep (land 10.26 km², lagoon 424.01 km²), both characterized by fragmented reef islets surrounding deep central lagoons. The following table summarizes land and lagoon areas for select Ratak atolls and islands, based on geological surveys:| Atoll/Island | Land Area (km²) | Lagoon Area (km²) | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Majuro | 9.17 | 295.05 | 64 islets, connected by causeways; urban development on eastern rim |

| Maloelap | 9.82 | 972.72 | Extensive reef with multiple passes; diverse pinnacle structures |

| Likiep | 10.26 | 424.01 | Historic copra sites; shallow fringing reefs |

| Wotje | 8.18 | 624.34 | Scattered islets; deep lagoon channels |

| Erikub | 1.53 | 230.30 | Remote, uninhabited; intact outer reefs |

| Ailuk | 5.36 | 177.34 | Patch reefs in lagoon; high fish biomass near passes |

| Utirik | 2.43 | 57.73 | Narrow rim; vulnerable to storm surges |

| Aur | 5.62 | 239.78 | Southern exposure; abundant coral genera |

| Mejit (island) | 1.86 | None | Raised coral; no enclosing reef |

| Jemo (island) | 0.16 | None | Small isolated islet; minimal vegetation |