Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Ralik.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ralik

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

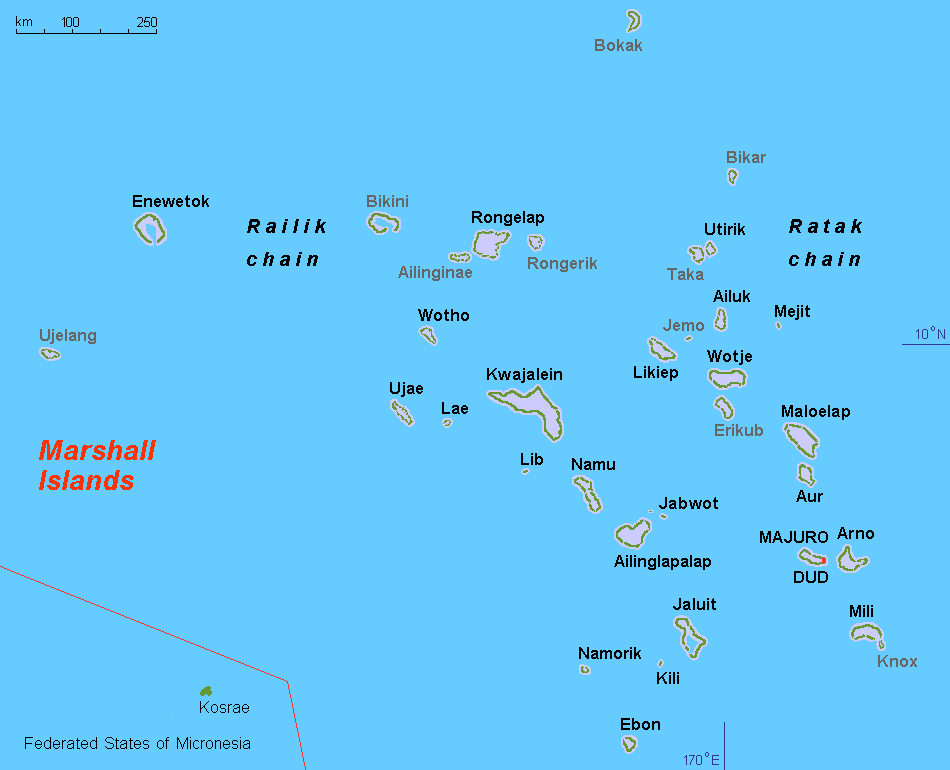

The Ralik Chain (Marshallese: Rālik, [rˠæːlʲik][1]) is a chain of islands within the island nation of the Marshall Islands. Ralik means "sunset". It is west of the Ratak Chain. In 1999 the total population of the Ralik islands was 19,915.[citation needed] Christopher Loeak, who became President of the Marshall Islands in 2012, was formerly Minister for the Ralik Chain.

Key Information

List of atolls and isolated islands in the chain:

Language

[edit]The Rālik Chain is home to the Rālik dialect (or western dialect) of the Marshallese language. It is mutually intelligible with the Ratak dialect (or eastern dialect) located on the Ratak Chain. The two dialects differ mainly in lexicon and in certain regular phonological reflexes.

References

[edit]Ralik

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

Geography

Location and Physical Features

The Ralik Chain forms the western of the two parallel island chains comprising the Republic of the Marshall Islands, extending in a northwest-southeast orientation across the central North Pacific Ocean, approximately halfway between Hawaii and Australia.[5] Named "Ralik," meaning "sunset" in the Marshallese language, it contrasts with the eastern Ratak Chain ("sunrise"), reflecting their relative positions.[6] The chain spans latitudes roughly from 5° to 11° N and longitudes 160° to 171° E, encompassing numerous atolls and isolated coral islands dispersed over a vast oceanic expanse.[7] Physically, the Ralik Chain is characterized by low-lying coral atolls, where narrow reef rims of sand and coral debris enclose large central lagoons, with individual islets rarely exceeding a few square kilometers in land area.[8] Elevations across the chain are minimal, typically 2-3 meters above mean sea level, with no significant hills or mountains; the highest points in the broader Marshall Islands reach about 10 meters.[9] These formations result from coral growth on submerged volcanic seamounts, lacking freshwater rivers or lakes and relying on rainwater catchment and lens aquifers for water supply.[5] Major atolls include Kwajalein, site of extensive lagoon systems, and Enewetak, both exemplifying the chain's reef-enclosed structure vulnerable to tidal influences and erosion.[10] The chain's physical configuration supports limited terrestrial biodiversity, dominated by coconut palms, pandanus, and salt-tolerant shrubs, while marine features like fringing reefs and lagoon ecosystems host diverse coral and fish species.[11] Soil is thin and sandy, derived from coral limestone, constraining agriculture to root crops and copra production.[5]Climate and Environment

The Ralik Chain experiences a tropical maritime climate with negligible seasonal temperature fluctuations, where mean daily highs range from 26°C to 31°C year-round, accompanied by persistently high humidity levels exceeding 80% on average.[12] Trade winds from the northeast dominate during the dry season (December to April), providing some relief from the heat, while the wet season (May to November) features calmer conditions influenced by the Intertropical Convergence Zone and occasional westerly winds.[13] Precipitation varies significantly by latitude within the chain, reflecting a north-south gradient; northern atolls such as Enewetak receive under 1,250 mm annually, whereas central locations like Kwajalein average around 2,540 mm per year, with wet-season months peaking at approximately 300 mm and dry-season totals near 100 mm.[13][14] Long-term records from Kwajalein indicate a slight declining trend in rainfall, at about 84 mm per decade since 1950, potentially linked to shifts in the El Niño-Southern Oscillation.[13] The natural environment consists of low-elevation coral atolls, with land surfaces rarely surpassing 2 meters above sea level and enclosing shallow lagoons rimmed by fringing reefs that foster biodiverse marine habitats, including diverse scleractinian corals, reef-associated fish, and benthic invertebrates.[13] Terrestrial ecosystems are constrained by saline soils and limited freshwater, supporting mainly drought- and salt-tolerant species like Cocos nucifera (coconut palms) and Pandanus tectorius. These fragile systems are acutely vulnerable to rising sea levels, measured at 7 mm per year since 1993 via tide gauges, which drive chronic erosion, saltwater intrusion into groundwater lenses, and stress on reefs from elevated seawater temperatures and declining aragonite saturation (from 4.5 to about 3.9 by 2000).[13] Infrequent but intensifying tropical cyclones and episodic droughts, as seen in severe conditions at Kwajalein and nearby atolls in early 2024, further compound these pressures.[13][15]History

Pre-Colonial and Early Contact Period

The Ralik Chain, comprising the western group of atolls in the Marshall Islands archipelago, was initially settled by Micronesian peoples through long-distance voyaging in outrigger canoes, with archaeological evidence from Kwajalein Atoll indicating human occupation beginning around 100 BCE to 1 CE. This early presence is supported by sediment layers containing artifacts and signs of land use, such as earth ovens and modified landscapes for taro cultivation and habitation. These settlers, part of broader Austronesian migrations across the Pacific, adapted to the low-lying coral atolls by developing intensive marine resource strategies, including fishing, shellfish gathering, and coconut processing, alongside limited agriculture on islet interiors.[10] Indigenous society in the Ralik Chain was matrilineal and hierarchical, structured around extended lineages (bwij) that traced descent and land rights through female lines, with flexible alliances for resource sharing and defense. Authority was distributed among local chiefs (iroij) managing individual atolls or islet groups, under a paramount chief (iroijlaplap) exerting influence over the broader chain, though political unity was absent and inter-chiefdom warfare over territory and prestige occurred periodically, as in conflicts around 1800 involving Ralik leaders. Navigation expertise was central, employing woven stick charts (rebbelib) to map wave patterns, currents, and island swells, enabling sustained voyaging and cultural exchange within the chain and occasionally to the eastern Ratak Chain. Social organization emphasized communal labor in canoe building, house construction, and weaving, with oral traditions preserving genealogies, myths, and navigational knowledge.[16][17][18] European contact commenced with the sighting of Marshall Islands atolls by Spanish explorer Alonso de Salazar on August 21, 1526, during his voyage on the Santa Maria de la Victoria, marking the first recorded European observation of the region, though no landing or interaction ensued. A subsequent Spanish expedition under Álvaro de Saavedra in 1529 approached some atolls but failed to make direct contact due to adverse conditions. These early sightings prompted nominal Spanish claims over select Ralik and Ratak atolls by 1565, yet visits remained sporadic and non-colonizing for centuries, with minimal disruption to local societies until whalers and traders increased in the late 18th century. British vessels conducted brief trades at eastern atolls like Mili in 1788, introducing iron tools and firearms, but Ralik communities experienced limited direct engagement until German commercial interests in the 1870s.[19][20]Colonial Administration

The Ralik Chain, forming the western portion of the Marshall Islands archipelago, experienced nominal Spanish sovereignty after Spain formally claimed the islands in 1874, though effective control was limited to occasional exploratory or missionary visits with no established administrative infrastructure.[21] Spanish influence remained peripheral, focused on broader Pacific claims rather than localized governance or economic exploitation in remote atolls like those in Ralik.[22] Germany asserted a protectorate over the Marshall Islands, including Ralik, in 1885 via diplomatic agreements that effectively transferred Spanish rights without conflict, marking the onset of structured colonial administration.[21] Initial governance was outsourced to the Jaluit Gesellschaft, a Hamburg-based trading company chartered in 1887 with a 25-year concession to administer the protectorate, collect taxes, maintain order, and monopolize copra trade—the primary economic activity—in exchange for annual subsidies to the German Foreign Office.[23] [24] The company established trading stations and administrative outposts primarily on Jaluit Atoll in the Ralik Chain, which became the central hub, alongside Ebon Atoll, facilitating copra exports that reached over 10,000 tons annually by the 1890s.[21] Rule was indirect, preserving the authority of Marshallese high chiefs (iroij) for internal disputes and land matters while German commissioners enforced trade regulations, conducted censuses (recording about 15,000 inhabitants in 1900), and introduced limited public works like wells and schools emphasizing practical skills.[21] Direct imperial oversight increased after 1899, with the Jaluit station elevated to district headquarters under a landeshauptmann, though the company's economic dominance persisted until the concession's partial lapse around 1905.[24] Japanese naval forces occupied the Marshall Islands in October 1914 during World War I, capturing Jaluit Atoll without resistance and displacing German personnel, thereby initiating military administration across Ralik and the broader archipelago.[25] [26] Jaluit retained its role as the administrative center for the islands under Japanese command, serving as a base for patrols and trade oversight until 1920.[21] Following the Treaty of Versailles, the League of Nations awarded Japan a Class C mandate in 1920, incorporating the Marshalls into the South Seas Mandate with civilian governance directed from Koror in Palau, though Jaluit hosted the district office handling local affairs, shipping, and enforcement.[25] [27] Administration emphasized economic assimilation, promoting Japanese immigration (reaching several thousand by the 1930s, concentrated on larger atolls), copra and fishing expansion, and infrastructure such as seaplane ramps, wireless stations, and elementary schools teaching Japanese language and loyalty to the emperor, while subordinating iroij authority through appointed councils.[28] [29] Fortification and resource extraction accelerated in the late 1930s amid rising militarism, but pre-war oversight in remote Ralik atolls remained light, relying on itinerant officials and local intermediaries.[28]World War II and Japanese Occupation

The Ralik Chain fell under Japanese control following the Empire of Japan's seizure of the Marshall Islands from Germany on October 3, 1914, during World War I, with formal administration established via a League of Nations Class C mandate granted on December 17, 1920.[5] Jaluit Atoll, located in the Ralik Chain, served as the primary administrative center for the Japanese South Seas Mandate, housing the Jaluit Branch Bureau that oversaw governance, economic activities, and later military preparations across the islands.[30] [31] Under Japanese rule, the chain's economy centered on copra production, with Marshallese locals increasingly subjected to forced labor drafts for plantation work and infrastructure projects, alongside influxes of Japanese settlers and Korean laborers that altered demographic balances and strained local resources.[32] In violation of the mandate's non-militarization clauses, Japan initiated fortifications across the Ralik Chain in the late 1930s, constructing airfields, seaplane ramps, coastal gun batteries, and bunkers on key atolls such as Kwajalein, Enewetak, and Jaluit to support defensive and offensive operations in the Pacific.[33] [34] Kwajalein Atoll, the largest in the world and strategically vital in the western Ralik Chain, received extensive defenses including pillboxes, trenches, and artillery positions manned by approximately 8,000 Japanese troops by early 1944. These preparations reflected Japan's broader imperial strategy, though they imposed hardships on indigenous populations through conscripted construction labor and resource requisitions amid growing wartime shortages. As World War II escalated following Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Ralik Chain served as a peripheral outpost for Japanese naval and air operations, subjected to initial U.S. reconnaissance and bombing raids starting in late 1942.[28] Intensive U.S. air and naval bombardment commenced in November 1943 under preparatory strikes for Operation Flintlock, targeting Japanese installations on Kwajalein and Enewetak to soften defenses.[35] The U.S. assault on Kwajalein Atoll began on January 31, 1944, with landings by the 7th Infantry Division on Kwajalein Island and the 4th Marine Division on Roi-Namur; fierce close-quarters combat amid coral terrain and entrenched positions resulted in near-total annihilation of the Japanese garrison, with over 7,800 killed and only 174 captured, at a cost of 372 U.S. dead and 1,582 wounded. Enewetak Atoll followed from February 17-23, 1944, where U.S. forces, including the 27th Infantry Division and 4th and 22nd Marines, overcame dug-in Japanese defenders on Engebi, Eniwetok, and Parry islands, killing about 2,700 troops while suffering 313 fatalities.[35] While Kwajalein and Enewetak were secured as U.S. bases by March 1944, enabling further advances toward the Marianas, other Ralik atolls like Jaluit, Wotje, and Taroa—fortified but deemed less critical—were subjected to sustained aerial and naval bombardment but bypassed for direct assault, with their Japanese garrisons isolated and surrendering en masse after Japan's capitulation on September 2, 1945.[30] [34] The operations inflicted severe devastation on island infrastructure and ecosystems, with unexploded ordnance and wrecks persisting as hazards, while local Marshallese populations endured collateral hardships including displacement, famine risks from disrupted agriculture, and occasional reprisals amid the fighting.[36]Post-War U.S. Trusteeship and Nuclear Testing

Following the Allied capture of the Marshall Islands from Japanese forces in 1944, the United States implemented a military government over the territory, including the Ralik Chain's atolls, to secure strategic Pacific outposts and transition from wartime occupation.[4] On July 18, 1947, the United Nations Trusteeship Council approved the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI), designating the U.S. as administering authority for a strategic trusteeship encompassing the Marshalls, with the Ralik Chain—spanning western atolls like Bikini, Enewetak, and Kwajalein—integrated into the Marshall Islands District under High Commissioner oversight from Saipan.[37] Initial Navy administration emphasized infrastructure repair, copra production resumption, and basic governance via local chiefs, but strategic priorities soon dominated, particularly nuclear weapons development amid emerging Cold War tensions.[38] The U.S. initiated nuclear testing in the remote Ralik Chain atolls due to their isolation and low population density, selecting Bikini Atoll in early 1946 for Operation Crossroads, even before formal trusteeship.[4] On February 10, 1946, approximately 167 Bikini residents were relocated to Rongerik Atoll after their paramount chief consented under U.S. assurances of temporary exile and biblical parallels to the Israelites, though many later reported misunderstanding the tests' scale and risks.[38] Two detonations followed on July 1 (Able, 23 kilotons) and July 25 (Baker, 21 kilotons), marking the first postwar nuclear tests and revealing underwater blast effects on ships and marine life.[4] Enewetak Atoll, similarly evacuated, hosted its first tests in 1948 under Operation Sandstone, with residents moved to Ujelang Atoll.[39] From 1946 to 1958, the U.S. conducted 67 nuclear detonations across the Marshall Islands, with 23 at Bikini (total yield 78.6 megatons) and 43 at Enewetak (over 30 megatons equivalent), comprising operations like Greenhouse (1951), Ivy (1952, including the first thermonuclear test), and Castle (1954).[2][39] The March 1, 1954, Castle Bravo shot at Bikini—intended as 5 megatons but yielding 15 due to lithium deuteride yield underestimation—produced fallout exceeding predictions, contaminating lagoon waters, vaporizing islands, and scattering plutonium across the atoll.[40] These tests, conducted under TTPI authority, prioritized weapons data over local habitability, with monitoring often limited by classified protocols. Relocated Ralik communities endured acute hardships, including malnutrition on inadequate substitute atolls and radiation exposure from contaminated food chains, leading to elevated thyroid cancer, leukemia, and birth defects documented in subsequent epidemiological studies.[41] Environmental legacies included cratered landmasses, cesium-137 soil uptake, and marine biodiversity loss, rendering much of Bikini and Enewetak uninhabitable without remediation; U.S. efforts during trusteeship focused on military cleanup, such as the 1950s Enewetak soil scraping, but left persistent hotspots.[39] While U.S. officials provided some medical aid and reparations promises, independent analyses highlight systemic underestimation of fallout risks and insufficient consent processes, contributing to ongoing distrust in TTPI governance.[4]Path to Independence and Modern Era

Following the conclusion of World War II, the United States assumed administration of the Marshall Islands, including the Ralik Chain, as part of the United Nations Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI) under a 1947 trusteeship agreement, with the goal of promoting self-governance and economic development.[42] This period saw extensive U.S. nuclear testing in Ralik Chain atolls, beginning with the evacuation of Bikini Atoll's 167 residents on February 10, 1946, for Operation Crossroads, which conducted two tests in July 1946 yielding a combined 23 kilotons.[2] Over the next decade, Bikini hosted 23 nuclear detonations from 1946 to 1958, including the 15-megaton Castle Bravo shot on March 1, 1954, which produced widespread radioactive fallout affecting Rongelap and Utirik atolls in the Ralik Chain and beyond.[2] Similarly, Enewetak Atoll underwent 43 tests from 1948 to 1958, totaling 31.7 megatons, featuring the first successful hydrogen bomb detonation (Ivy Mike, 10.4 megatons) on November 1, 1952; these operations displaced local populations and left enduring radiological contamination.[3] The nuclear program profoundly shaped the path to independence, as displaced Ralik communities from Bikini and Enewetak faced failed resettlement attempts amid health crises, including elevated cancer rates documented in subsequent studies of exposed populations.[41] By the 1970s, growing Micronesian demands for autonomy led to a 1978 referendum where Marshallese voters opted to separate from the broader TTPI federation, establishing a distinct constitutional convention.[43] On May 1, 1979, the Marshall Islands adopted its constitution, becoming self-governing with Amata Kabua as president, while negotiations proceeded for a Compact of Free Association (COFA) to formalize ties with the U.S., addressing nuclear compensation alongside defense and economic provisions.[42] The COFA was approved by U.S. Congress in 1985 and entered into force on October 21, 1986, granting the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI) full sovereignty while delegating defense responsibilities to the U.S. and providing annual aid payments, initially $1.5 billion over 15 years adjusted for nuclear impacts.[43] The UN Security Council terminated the trusteeship on December 22, 1990, affirming RMI independence.[42] In the modern era, the Ralik Chain has grappled with legacy effects of testing, including a 1975 U.S.-funded cleanup at Enewetak that entombed 85,000 cubic meters of radioactive waste in Runit Dome, which faces erosion risks from rising sea levels; Bikini remains uninhabitable for permanent return despite intermittent fishing by exiles.[39] The Nuclear Claims Tribunal, established under the 1986 COFA, awarded over $2.3 billion in claims by 2000 but received only partial U.S. funding, leaving many Ralik survivors undercompensated.[43] Contemporary RMI governance under the COFA, renewed in 2003 for 20 years with amendments in 2023, sustains economic dependence on U.S. grants comprising over 80% of federal revenue, funding health and environmental remediation in Ralik atolls amid challenges like climate-induced inundation threatening low-lying islands.[42] Efforts to diversify include tourism at safer Ralik sites like Jaluit, but nuclear stigma and contamination limit development, with ongoing U.S. support for monitoring radiation levels in food chains and groundwater.[3] Political stability persists under presidents like Hilda Heine since 2018, though disputes over COFA renegotiations highlight tensions between sovereignty and aid reliance.[43]Administrative Divisions

Major Atolls and Islands

The Ralik Chain, the western archipelago of the Marshall Islands, encompasses 18 atolls and islands spanning approximately 550 miles from northwest to southeast.[6] Key atolls include Kwajalein, the largest in the world by lagoon area, enclosing 1,125 square miles of water within a coral reef loop supporting around 97 islets and a total land area of roughly 6 square miles.[44] This atoll's strategic lagoon facilitated U.S. military operations during World War II and subsequent missile defense testing under a long-term lease agreement with the Republic of the Marshall Islands.[45] Bikini Atoll, positioned in the northern segment of the Ralik Chain about 305 kilometers east of Enewetak, comprises 23 islands encircling a central lagoon and was designated for U.S. nuclear experimentation.[2] Between 1946 and 1958, the atoll hosted 23 atomic detonations as part of Operations Crossroads, Castle, and others, rendering significant portions radioactive and displacing residents.[46][2] Enewetak Atoll, at the northwestern extremity, features 40 islands around a 50-mile-diameter lagoon and served as the primary site for 43 U.S. nuclear tests from 1948 to 1958.[39][3] These explosions, including thermonuclear devices, necessitated post-test radiological remediation efforts, including crater filling with contaminated soil shipped to Runit Island, where a concrete dome encapsulates waste.[39] The atoll's military history also includes its capture by U.S. forces in February 1944 during World War II.[3] Other significant atolls in the chain include Namdrik, consisting of two main islands utilized for traditional copra production and marine resource management, and Jaluit, a historical hub with multiple islets that functioned as a colonial administrative center under German and Japanese governance.[47] These atolls collectively support sparse populations reliant on fishing, subsistence agriculture, and remittances, with environmental challenges stemming from their remote, low-lying coral structures vulnerable to sea-level rise.[8]Local Governance Structure

The Ralik Chain's local governance combines elected municipal councils with a preserved traditional chiefly hierarchy, reflecting the Marshall Islands' hybrid constitutional framework. The chain includes multiple municipalities—such as those encompassing Kwajalein, Jaluit, and Enewetak atolls—each governed by an elected mayor and council elected every four years, handling day-to-day administration including public works, sanitation, and community welfare as outlined in the Local Government Act 1980.[48] These bodies derive authority from Article IX of the Constitution, which mandates local governments for decentralized service delivery while remaining subordinate to national oversight by the Ministry of Interior and Outer Islands.[49] Traditional authority persists through four Iroijlaplap (paramount chief) domains in the Ralik Chain, excluding Ujelang Atoll, as declared by the Customary Law (Ralik Chain) Act 1991, which codifies succession, land tenure, and dispute resolution under customary practices.[50] Each domain's Iroijlaplap exercises veto-like influence over local matters involving inheritance, resources, and cultural protocols, supported by subordinate titles like Alap (lineage heads) and Dri-jerbal (working chiefs) who manage labor and advisory roles. This structure interfaces with elected bodies via consultation requirements, ensuring chiefly consent for land-related decisions. At the chain level, the four Ralik Iroijlaplap (plus one from Ujelang) hold seats in the national Council of Iroij, established under Article III of the Constitution, which reviews bills impacting customs and can delay legislation for up to 90 days.[51] This council, comprising 12 total members (five from Ralik districts), embodies the paramount chieftaincy historically divided between the Ralik (sunset) and Ratak chains since pre-colonial times.[5] Local governance thus balances democratic elections—introduced post-independence in 1979—with chiefly veto powers, though tensions arise in resource allocation, as evidenced by disputes over nuclear-affected lands where traditional rights supersede municipal claims.[52]Demographics

Population Distribution

The population of the Ralik Chain is distributed unevenly across its inhabited atolls, with a 2021 census total of approximately 15,141 residents in 13 primary inhabited locales, representing about 36% of the national population of 42,418. This figure excludes uninhabited or minimally occupied atolls such as Bikini, Rongelap, and Ailinginae, which remain largely depopulated due to persistent radiological contamination from U.S. nuclear testing programs conducted from 1946 to 1958. Kwajalein Atoll dominates the distribution, hosting 9,789 individuals—over 64% of the chain's total—concentrated primarily on Ebeye Island, where economic activity revolves around employment at the U.S.-operated Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site.[53][53] Secondary population centers include Jaluit Atoll (1,409 residents), Ailinglaplap Atoll (1,175), and Namu Atoll (525), where communities rely on subsistence fishing, copra production, and limited remittances from urban migrants. Smaller atolls exhibit markedly lower densities: Ebon (469), Kili (415), Ujae (310), Namdrik (299), Enewetak (296), Lib (156), Lae (133), Wotho (88), and Jabat (75). These disparities stem from geographic isolation, scarce arable land (averaging less than 1 km² per atoll), vulnerability to climate-induced sea-level rise, and historical factors including forced relocations during nuclear tests and post-independence migration to urban hubs like Majuro in the Ratak Chain.[53][53]| Atoll | Population (2021) |

|---|---|

| Kwajalein | 9,789 |

| Jaluit | 1,409 |

| Ailinglaplap | 1,175 |

| Namu | 525 |

| Ebon | 469 |

| Kili | 415 |

| Ujae | 310 |

| Namdrik | 299 |

| Enewetak | 296 |

| Lib | 156 |

| Lae | 133 |

| Wotho | 88 |

| Jabat | 75 |

| Total | 15,141 |