Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

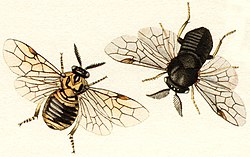

Sawfly

View on Wikipedia

| Sawfly Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Tenthredo mesomela | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Suborder: | Symphyta Gerstaecker, 1867[1] |

| Groups included | |

| Cladistically included but traditionally excluded taxa | |

Sawflies are wasp-like insects that belong to the suborder Symphyta within the order Hymenoptera. Their common name comes from the saw-shaped ovipositor of the female, which she uses to cut into plant tissue when laying eggs. The largest and most diverse group of sawflies is the Tenthredinoidea, a superfamily that includes most of the approximately 8,000 described species in more than 800 genera worldwide.[3]

Although Symphyta is traditionally ranked as a suborder, it is a paraphyletic grouping that represents several early lineages of Hymenoptera. The insects commonly called sawflies form a natural clade, however, this also includes the ancestors of the Apocrita—the ants, bees, and wasps.[4] Adult sawflies are distinguished from the Apocrita by the absence of a narrow "wasp waist" or petiole between the thorax and abdomen. In sawflies, these segments are broadly joined, which gives the body a smooth profile.[5]

Sawflies first appeared during the Triassic period, about 250 million years ago. The oldest known lineage, the Xyeloidea, is still represented by living species.[6] Around 200 million years ago, some sawfly lineages evolved a parasitoid lifestyle, with larvae that prey on other insects’ eggs or young.[7] Today, sawflies occur worldwide but they are most diverse in the temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere.[4]

Many sawflies are mimics of bees or wasps, and the female’s ovipositor is sometimes mistaken for a sting, though sawflies cannot sting.[7] Adults range in size from about 2.5 to 20 millimetres (3⁄32 to 25⁄32 in), with the largest species reaching about 55 millimetres (2+1⁄4 in) in length. Most species are herbivorous, feeding on foliage or other plant parts, while members of the Orussoidea are parasitoids.[3] Sawflies are preyed upon by birds, small mammals such as shrews, and predatory or parasitic insects including flies and other hymenopterans. The larvae of some species defend themselves by regurgitating irritating fluids or by clustering together for protection.[8]

The larvae resemble caterpillars but can be distinguished by their greater number of prolegs and the absence of crochets on the feet. Sawflies undergo complete metamorphosis with four distinct stages, from egg, larva, pupa to adult. Adult sawflies live only about a week, but the larval stage may last from months to more than a year depending on species and environment.[7] Many species reproduce through parthenogenesis, in which females produce fertile eggs without mating, though others reproduce sexually. Adults feed on pollen, nectar, sap, honeydew and sometimes on the hemolymph of other insects, using mouthparts adapted for these varied diets.[9]

Females use their ovipositors to cut into plant tissue—or into the bodies of host insects in parasitoid species—and deposit eggs in clusters called rafts or pods. As the larvae mature, they seek protected sites such as soil or under bark to pupate.[6]

Several species are significant pests. The pine sawfly can cause serious defoliation in forestry, while sawflies such as the iris sawfly damage ornamental plants. Outbreaks of larvae may lead to dieback or tree death. Control methods include the use of insecticides, natural predators and parasitoids, and manual removal of larvae.[8]

Recent phylogenomic research has refined the evolutionary relationships among sawfly lineages, placing Xyeloidea as sister to all other Hymenoptera and revealing complex gene-tree discordance and introgression events.[6][3] These studies highlight key evolutionary innovations such as the transition to parasitoidism and the development of the wasp waist, which underlie the diversification of the order.[4][5]

Etymology

[edit]

The suborder name "Symphyta" derives from the Greek word symphyton, meaning 'grown together', referring to the group's distinctive lack of a wasp waist between prostomium and peristomium.[10] Its common name, "sawfly", derives from the saw-like ovipositor that is used for egg-laying, in which a female makes a slit in either a stem or plant leaf to deposit the eggs.[11] The first known use of this name was in 1773.[12] Sawflies are also known as "wood-wasps".[13]

Phylogeny

[edit]

In his original description of Hymenoptera in 1863, German zoologist Carl Gerstaecker divided them into three groups, Hymenoptera aculeata, Hymenoptera apocrita and Hymenoptera phytophaga.[14] However, four years later in 1867, he described just two groups, H. apocrita syn. genuina and H. symphyta syn. phytophaga.[1] Consequently, the name Symphyta is given to Gerstaecker as the zoological authority. In his description, Gerstaecker distinguished the two groups by the transfer of the first abdominal segment to the thorax in the Apocrita, compared to the Symphyta. Consequently, there are only eight dorsal half segments in the Apocrita, against nine in the Symphyta. The larvae are distinguished in a similar way.[15]

The Symphyta have therefore traditionally been considered, alongside the Apocrita, to form one of two suborders of Hymenoptera.[16][17] Symphyta are the more primitive group, with comparatively complete venation, larvae that are largely phytophagous, and without a "wasp-waist", a symplesiomorphic feature. Together, the Symphyta make up less than 10% of hymenopteran species.[18] While the terms sawfly and Symphyta have been used synonymously, the Symphyta have also been divided into three groups, true sawflies (phyllophaga), woodwasps or xylophaga (Siricidae), and Orussidae. The three groupings have been distinguished by the true sawflies' ventral serrated or saw-like ovipositor for sawing holes in vegetation to deposit eggs, while the woodwasp ovipositor penetrates wood and the Orussidae behave as external parasitoids of wood-boring beetles. The woodwasps themselves are a paraphyletic ancestral grade. Despite these limitations, the terms have utility and are common in the literature.[17]

While most hymenopteran superfamilies are monophyletic, as is Hymenoptera, the Symphyta has long been seen to be paraphyletic.[19][20] Cladistic methods and molecular phylogenetics are improving the understanding of relationships between the superfamilies, resulting in revisions at the level of superfamily and family.[21] The Symphyta are the most primitive (basal) taxa within the Hymenoptera (some going back 250 million years), and one of the taxa within the Symphyta gave rise to the monophyletic suborder Apocrita (wasps, bees, and ants).[18][20] In cladistic analyses the Orussoidea are consistently the sister group to the Apocrita.[17][18]

The oldest unambiguous sawfly fossils date back to the Middle or Late Triassic. These fossils, from the family Xyelidae, are the oldest of all Hymenoptera.[22] One fossil, Archexyela ipswichensis from Queensland is between 205.6 and 221.5 million years of age, making it among the oldest of all sawfly fossils.[23] More Xyelid fossils have been discovered from the Middle Jurassic and the Cretaceous, but the family was less diverse then than during the Mesozoic and Tertiary. The subfamily Xyelinae were plentiful during these time periods, in which Tertiary faunas were dominated by the tribe Xyelini; these are indicative of a humid and warm climate.[24][25][26]

The cladogram is based on Schulmeister 2003.[27][28]

| Symphyta within Hymenoptera | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Symphyta (red bar) are paraphyletic as Apocrita are excluded. |

Taxonomy

[edit]

There are approximately 8,000 species of sawfly in more than 800 genera, although new species continue to be discovered.[29][30][31] However, earlier studies indicated that 10,000 species grouped into about 1,000 genera were known.[32] Early phylogenies such as that of Alexandr Rasnitsyn, based on morphology and behaviour, identified nine clades which did not reflect the historical superfamilies.[33] Such classifications were replaced by those using molecular methods, starting with Dowton and Austin (1994).[34] As of 2013, the Symphyta are treated as nine superfamilies (one extinct) and 25 families. Most sawflies belong to the Tenthredinoidea superfamily, with about 7,000 species worldwide. Tenthredinoidea has six families, of which Tenthredinidae is by far the largest with some 5,500 species.[2][35]

Extinct taxa are indicated by a dagger (†).

Superfamilies and families

[edit]- Superfamily Anaxyeloidea (Martynov, 1925)

- Family Anaxyelidae (Martynov, 1925) (1 species) and †12 genera

- Superfamily Cephoidea (Newman, 1834) (1 and †1 family)

- Superfamily †Karatavitoidea (Rasnitsyn, 1963) (1 family)

- Family †Karatavitidae (Rasnitsyn, 1963) (7 genera)

- Superfamily Orussoidea (Newman, 1834) (1 and †1 family)

- Family Orussidae (Newman, 1834) (16 genera, 82 spp.) and †3 genera

- Superfamily Pamphilioidea (Cameron, 1890) (2 and †1 families) (syn. Megalodontoidea)

- Family Megalodontesidae (Konow, 1897) (1 genera, 42 spp.) and †1 genus

- Family Pamphiliidae (Cameron, 1890) (10 genera, 291 spp.) and †3 genera

- Superfamily Siricoidea (Billberg, 1820) (2 and †5 families)

- Family Siricidae (Billberg, 1820) (11 genera, 111 spp.) and †9 genera

- Superfamily Tenthredinoidea (Latreille, 1803) (6 and †2 families)

- Family Argidae (Konow, 1890) (58 genera, 897 spp.) and †1 genus

- Family Blasticotomidae (Thomson, 1871) (2 genera, 12 spp.) and †1 genus

- Family Cimbicidae (W. Kirby, 1837) (16 genera, 182 spp.) and †6 genera

- Family Diprionidae (Rohwer, 1910) (11 genera, 136 spp.) and †2 genera

- Family Pergidae (Rohwer, 1911) (60 genera, 442 spp.)

- Family Tenthredinidae (Latreille, 1803) (400 genera, 5,500 spp.) and †14 genera

- Superfamily Xiphydrioidea (Leach, 1819)

- Family Xiphydriidae (Leach, 1819) (28 genera, 146 spp.)

- Superfamily Xyeloidea (Newman, 1834)

- Family Xyelidae (Newman, 1834) (5 genera, 63 spp.) and †47 genera

Description

[edit]Many species of sawfly have retained their ancestral attributes throughout time, specifically their plant-eating habits, wing veins and the unmodified abdomen, where the first two segments appear like the succeeding segments.[36] The absence of the narrow wasp waist distinguishes sawflies from other members of hymenoptera, although some are Batesian mimics with coloration similar to wasps and bees, and the ovipositor can be mistaken for a stinger.[37] Most sawflies are stubby and soft-bodied, and fly weakly.[38] Sawflies vary in length: Urocerus gigas, which can be mistaken as a wasp due to its black-and-yellow striped body, can grow up to 20 mm (3⁄4 in) in length, but among the largest sawflies ever discovered was Hoplitolyda duolunica from the Mesozoic, with a body length of 55 mm (2+1⁄4 in) and a wingspan of 92 mm (3+1⁄2 in).[37][39] The smaller species only reach lengths of 2.5 mm (3⁄32 in).[40]

Heads of sawflies vary in size, shape and sturdiness, as well as the positions of the eyes and antennae. They are characterised in four head types: open head, maxapontal head, closed head and genapontal head. The open head is simplistic, whereas all the other heads are derived.[41] The head is also hypognathous, meaning that the lower mouthparts are directed downwards. When in use, the mouthparts may be directed forwards, but this is only caused when the sawfly swings its entire head forward in a pendulum motion.[42] Unlike most primitive insects, the sutures (rigid joints between two or more hard elements on an organism) and sclerites (hardened body parts) are obsolescent or absent. The clypeus (a sclerite that makes up an insects "face") is not divided into a pre- and postclypeus, but rather separated from the front.[43] The antennal sclerites are fused with the surrounding head capsule, but these are sometimes separated by a suture. The number of segments in the antennae vary from six in the Accorduleceridae to 30 or more in the Pamphiliidae.[44] The compound eyes are large with a number of facets, and there are three ocelli between the dorsal portions of the compound eyes.[43] The tentorium comprises the whole inner skeleton of the head.[45]

Three segments make up the thorax: the mesothorax, metathorax and prothorax, as well as the exoskeletal plates that connect with these segments.[46] The legs have spurs on their fourth segments, the tibiae.[47] Sawflies have two pairs of translucent wings. The fore and hind wings are locked together with hooks.[48] Parallel development in sawfly wings is most frequent in the anal veins. In all sawflies, 2A and 3A tend to fuse with the first anal vein. This occurs in several families including Argidae, Diprionidae and Cimbicidae.[49]

The larvae of sawflies are easily mistaken for lepidopteran larvae (caterpillars). However, several morphological differences can distinguish the two: while both larvae share three pairs of thoracic legs and an apical pair of abdominal prolegs, lepidopteran caterpillars have four pairs of prolegs on abdominal segments 3–6 while sawfly larvae have five pairs of prolegs located on abdominal segments 2–6; crochets are present on lepidopteran larvae, whereas on sawfly larvae they are not; the prolegs of both larvae gradually disappear by the time they burrow into the ground, therefore making it difficult to distinguish the two; and sawfly larvae only have a single pair of minute eyes, whereas lepidopteran larvae have four to six eyes on each side of the head.[16][37] Sawfly larvae behave like lepidopteran larvae, walking about and eating foliage. Some groups have larvae that are eyeless and almost legless; these larvae make tunnels in plant tissues including wood.[38] Many species of sawfly larvae are strikingly coloured, exhibiting colour combinations such as black and white while others are black and yellow. This is a warning colouration because some larvae can secrete irritating fluids from glands located on their undersides.[37]

Distribution

[edit]Sawflies are widely distributed throughout the world.[50] The largest family, the Tenthredinidae, with some 5,000 species, are found on all continents except Antarctica, though they are most abundant and diverse in the temperate regions of the northern hemisphere; they are absent from New Zealand and there are few of them in Australia. The next largest family, the Argidae, with some 800 species, is also worldwide, but is most common in the tropics, especially in Africa, where they feed on woody and herbaceous angiosperms. Of the other families, the Blasticotomidae and Megalodontesidae are Palearctic; the Xyelidae, Pamphilidae, Diprionidae, Cimbicidae, and Cephidae are Holarctic, while the Siricidae are mainly Holarctic with some tropical species. The parasitic Orussidae are found worldwide, mostly in tropical and subtropical regions. The wood-boring Xiphydriidae are worldwide, but most species live in the subtropical parts of Asia.[29]

Behaviour and ecology

[edit]

Sawflies are mostly herbivores, feeding on plants that have a high concentration of chemical defences. These insects are either resistant to the chemical substances, or they avoid areas of the plant that have high concentrations of chemicals.[51] The larvae primarily feed in groups; they are folivores, eating plants and fruits on native trees and shrubs, though some are parasitic.[11][52][53] However, this is not always the case; Monterey pine sawfly (Itycorsia) larvae are solitary web-spinners that feed on Monterey pine trees inside a silken web.[54] The adults feed on pollen and nectar.[52]

Sawflies are eaten by a wide variety of predators. While many birds find the larvae distasteful, some such as the currawong (Strepera) and stonechats (Saxicola) eat both adults and larvae.[55][56] The larvae are an important food source for the chicks of several birds, including partridges.[57] Sawfly and moth larvae form one third of the diet of nestling corn buntings (Emberiza calandra), with sawfly larvae being eaten more frequently on cool days.[58] Black grouse (Tetrao tetrix) chicks show a strong preference for sawfly larvae.[59][60] Sawfly larvae formed 43% of the diet of chestnut-backed chickadees (Poecile rufescens).[54] Small carnivorous mammals such as the masked shrew (Sorex cinereus), the northern short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda) and the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus) predate heavily on sawfly cocoons.[61] Insects such as ants and certain species of predatory wasps (Vespula vulgaris) eat adult sawflies and the larvae, as do lizards and frogs.[62][63] Pardalotes, honeyeaters and fantails (Rhipidura) occasionally consume laid eggs, and several species of beetle larvae prey on the pupae.[56]

The larvae have several anti-predator adaptations. While adults are unable to sting, the larvae of species such as the spitfire sawfly regurgitate a distasteful irritating liquid, which makes predators such as ants avoid the larvae.[11][64] In some species, the larvae cluster together, reducing their chances of being killed, and in some cases form together with their heads pointing outwards or tap their abdomens up and down.[56][65] Some adults bear black and yellow markings that mimic wasps.[37]

Parasites

[edit]Sawflies are hosts to many parasitoids, most of which are parasitic Hymenoptera; more than 40 species are known to attack them. However, information regarding these species is minimal, and fewer than 10 of these species actually cause a significant impact on sawfly populations.[66] Many of these species attack their hosts in the grass or in other parasitoids.[clarification needed] Well known and important parasitoids include Braconidae, Eulophidae and Ichneumonidae. Braconid wasps attack sawflies in many regions throughout the world, in which they are ectoparasitoids, meaning that the larvae live and feed outside of the hosts body; braconids have more of an impact on sawfly populations in the New World than they do in the Old World, possibly because there are no ichneumonid parasitoids in North America. Some braconid wasps that attack sawflies include Bracon cephi, B. lisogaster, B. terabeila and Heteropilus cephi.[66][67][68] Female braconids locate sawfly larvae through the vibrations they produce when feeding, followed by inserting the ovipositor and paralysing the larva before laying eggs inside the host. These eggs hatch inside the larva within a few days, where they feed on the host. The entire host's body may be consumed by the braconid larvae, except for the head capsule and epidermis. The larvae complete their development within two or three weeks.[66]

Ten species of wasps in the family Ichneumonidae attack sawfly populations, although these species are usually rare. The most important parasitoids in this family are species in the genus Collyria. Unlike braconids, the larvae are endoparasitoids, meaning that the larvae live and feed inside the hosts body.[66] One well known ichneumonid is Collyria coxator, which is a dominant parasitoid of C. pygmaeus. Recorded parasitism rates in Europe are between 20–76%, and as many as eight eggs can be found in a single larva, but only one Collyria individual will emerge from its host. The larva may remain inside of their host until spring, where it emerges and pupates.[66]

Several species in the family Eulophidae attack sawflies, although their impact is low. Two species in the genus Pediobius have been studied; the two species are internal larval parasitoids and have only been found in the northern hemisphere. Parasitism of sawflies by eulophids in grass exceeds 50%, but only 5% in wheat. It is unknown as to why the attack rate in wheat is low.[69] Furthermore, some fungal and bacterial diseases are known to infect eggs and pupa in warm wet weather.[56]

Outbreaks of certain sawfly species, such as Diprion polytomum, have led scientists to investigate and possibly collect their natural enemies to control them. Parasites of D. polytomum have been extensively investigated, showing that 31 species of hymenopterous and dipterous parasites attack it. These parasites have been used in successful biological control against pest sawflies, including Cephus cinctus throughout the 1930s and 1950s and C. pygmaeus in the 1930s and 1940s.[70][71]

Life cycle and reproduction

[edit]

Like all other hymenopteran insects, sawflies go through a complete metamorphosis with four distinct life stages – egg, larva, pupa and adult.[72] Many species are parthenogenetic, meaning that females do not need fertilization to create viable eggs. Unfertilized eggs develop as male, while fertilized eggs develop into females (arrhenotoky). The lifespan of an individual sawfly is two months to two years, though the adult life stage is often very short (approximately 7 – 9 days), only long enough for the females to lay their eggs.[37][56][73] The female uses its ovipositor to drill into plant material to lay her eggs (though the family Orussoidea lay their eggs in other insects). Plant-eating sawflies most commonly are associated with leafy material but some specialize on wood, and the ovipositors of these species (such as the family Siricidae) are specially adapted for the task of drilling through bark. Once the incision has been made, the female will lay as many as 30 to 90 eggs. Females avoid the shade when laying their eggs because the larvae develop much slower and may not even survive, and they may not also survive if they are laid on immature and glaucous leaves. Hence, female sawflies search for young adult leaves to lay their eggs on.[37][56]

These eggs hatch in two to eight weeks, but such duration varies by species and also by temperature. Until the eggs have hatched, some species such as the small brown sawfly will remain with them and protects the eggs by buzzing loudly and beating her wings to deter predators. There are six larval stages that sawflies go through, lasting 2 – 4 months, but this also depends on the species. When fully grown, the larvae emerge from the trees en masse and burrow themselves into the soil to pupate. During their time outside, the larvae may link up to form a large colony if many other individuals are present. They gather in large groups during the day which gives them protection from potential enemies, and during the night they disperse to feed. The emergence of adults takes awhile, with some emerging anywhere between a couple months to 2 years. Some will reach the ground to form pupal chambers, but others may spin a cocoon attached to a leaf. Larvae that feed on wood will pupate in the tunnels they have constructed. In one species, the jumping-disc sawfly (Phyllotoma aceris) forms a cocoon which can act like a parachute. The larvae live in sycamore trees and do not damage the upper or lower cuticles of leaves that they feed on. When fully developed, they cut small perforations in the upper cuticle to form a circle. After this, they weave a silk hammocks within the circle; this silk hammock never touches the lower cuticle. Once inside, the upper-cuticle's disc separates and descends towards the surface with the larvae attaching themselves to the hammock. Once they reach the round, the larvae work their way into a sheltered area by jerking their discs along.[37][56]

The majority of sawfly species produce a single generation per year, but others may only have one generation every two years. Most sawflies are female, making males rare.[56]

- Life cycle of the sawfly Cladius difformis, the bristly rose slug

-

Larva

-

Pupa, dorsal view

-

Pupa, ventral view

-

Female

-

Male

Relationship with humans

[edit]

Sawflies are major economic pests of forestry. Species in the Diprionidae, such as the pine sawflies, Diprion pini and Neodiprion sertifer, cause serious damage to pines in regions such as Scandinavia. D. pini larvae defoliated 500,000 hectares (1,200,000 acres) in the largest outbreak in Finland, between 1998 and 2001. Up to 75% of the trees may die after such outbreaks, as D. pini can remove all the leaves late in the growing season, leaving the trees too weak to survive the winter.[74] Little damage to trees only occurs when the tree is large or when there is minimal presence of larvae. Eucalyptus trees can regenerate quickly from damage inflicted by the larvae; however, they can be substantially damaged from outbreaks, especially if they are young. The trees can be defoliated completely and may cause "dieback", stunting or even death.[56]

Sawflies are serious pests in horticulture. Different species prefer different host plants, often being specific to a family or genus of hosts. For example, Iris sawfly larvae, emerging in summer, can quickly defoliate species of Iris including the yellow flag and other freshwater species.[75] Similarly the rose sawflies, Arge pagana and A. ochropus, defoliate rose bushes.[76]

The giant woodwasp or horntail, Urocerus gigas, has a long ovipositor, which with its black and yellow colouration make it a good mimic of a hornet. Despite the alarming appearance, the insect cannot sting.[77] The eggs are laid in the wood of conifers such as Douglas fir, pine, spruce, and larch. The larvae eat tunnels in the wood, causing economic damage.[78]

Alternative measures to control sawflies can be taken. Small-scale, mechanical methods include visually confirming larval presence on a plant and subsequently removing them, either by pruning damaged leaves or removing the larvae from the leaves they are on. Larvae typically try to remain hidden on the underside of foliage. Upon removing larvae and/or the affected leaves from plants, they may be dispatched by squishing, or, alternatively, the cut leaves with larvae still attached may be fed to birds; if larger animals do not prey upon them, other insects will. However, this is not practical or useful for some, thus the larvae can be quickly dispatched by simply dropping foliage into a vessel of plain or saltwater, diluted hydrogen peroxide or isopropyl alcohol, insecticidal soap, or other garden chemical. In large-scale, industrial settings, where beneficial insect predators can also be used to eliminate larvae, as well as parasites, which have both been previously used in control programs.[56][70] Small trees can be sprayed with a number of chemicals, including maldison, dimethoate, carbaryl, imidacloprid, etc., if removing larvae from trees is not effective enough.[56]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Gerstaecker, C. E. A. (1867). "Ueber die Gattung Oxybelus Latr. und die bei Berlin vorkommenden Arten derselben". Zeitschrift für die Gesammten Naturwissenschaften (in German). 30 (7): 1–144.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Aguiar, A. P.; Deans, A. R.; Engel, M. S.; Forshage, M.; Huber, J. T.; Jennings, J. T.; Johnson, N. F.; Lelej, A. S.; Longino, J. T.; Lohrmann, V.; Mikó, I.; Ohl, M.; Rasmussen, C.; Taeger, A.; Yu, D. S. K. (2013). "Order Hymenoptera. In: Zhang, Z.-Q. (ed.) Animal biodiversity: an outline of higher-level classification and survey of taxonomic richness". Zootaxa. 3703 (1): 51–62. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3703.1.12. PMID 26146682.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

Wutke2024was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

Peters2017was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Blaimer2023was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

Herrig2024was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

Oeyen2020was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Davis2023was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Jervis2000was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Symphyta". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ a b c Australian Museum (20 October 2009). "Animal Species: Sawflies". Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ^ "Sawfly". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ Gordh, G.; Headrick, D.H. (2011). A Dictionary of Entomology (2nd ed.). Wallingford: CABI. p. 1344. ISBN 978-1-84593-542-9.

- ^ Carus, J. V.; Gerstaecker, C. E. A. (1863). Gerstaecker, A.; Victor Carus, J. (eds.). Handbuch der Zoologie (in German). Vol. 2: Arthropoden, Raderthiere, Würmer, Echinodermen, Coelenteraten und Protozoen. Leipzig, Saxony: Engelmann. p. 189. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.1399. OCLC 2962429.

- ^ Dallas, W. S. (1867). Günther, A. C. L. G. (ed.). The Record of Zoological Literature. Vol. 3–4: Insecta. London, UK: John van Voorst. p. 307. OCLC 6344527.

- ^ a b Goulet & Huber 1993, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Sharkey, M. J. (2007). "Phylogeny and classification of Hymenoptera" (PDF). Zootaxa. 1668: 521–548. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1668.1.25.

- ^ a b c Mao, M.; Gibson, T.; Dowton, M. (2015). "Higher-level phylogeny of the Hymenoptera inferred from mitochondrial genomes". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 84: 34–43. Bibcode:2015MolPE..84...34M. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.12.009. PMID 25542648.

- ^ Sharkey, M. J.; Carpenter, J. M.; Vilhelmsen, L.; Heraty, J.; Liljeblad, J.; Dowling, A. P. G.; et al. (2012). "Phylogenetic relationships among superfamilies of Hymenoptera". Cladistics. 28 (1): 80–112. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.721.8852. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2011.00366.x. PMID 34861753. S2CID 33628659.

- ^ a b Song, S.-N.; Tang, P.; Wei, S.-J.; Chen, X.-X. (2016). "Comparative and phylogenetic analysis of the mitochondrial genomes in basal hymenopterans". Scientific Reports. 6 20972. Bibcode:2016NatSR...620972S. doi:10.1038/srep20972. PMC 4754708. PMID 26879745.

- ^ Hennig, W. (1969). Die Stammesgeschichte der Insekten. Frankfurt: Waldemar Kramer. pp. 291, 359. ASIN B0000BRK5P. OCLC 1612960.

- ^ Hermann, Henry R. (1979). Social Insects. Vol. 1. Oxford: Elsevier Science. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-323-14979-2.

- ^ Engel, M. S. (2005). "A new sawfly from the Triassic of Queensland (Hymenoptera: Xyelidae)". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 51 (2): 558.

- ^ Wang, M.; Rasinitsyn, A. P.; Ren, Dong (2014). "Two new fossil sawflies (Hymenoptera, Xyelidae, Xyelinae) from the Middle Jurassic of China". Acta Geologica Sinica. 88 (4): 1027–1033. Bibcode:2014AcGlS..88.1027W. doi:10.1111/1755-6724.12269. S2CID 129371522.

- ^ Wang, M.; Gao, T.; Shih, C.; Rasinitsyn, A. P.; Ren, D. (2016). "The diversity and phylogeny of Mesozoic Symphyta (Hymenoptera) from Northeastern China". Acta Geologica Sinica. 90 (1): 376–377. Bibcode:2016AcGlS..90..376W. doi:10.1111/1755-6724.12662. S2CID 87932664.

- ^ Rasnitsyn, A. P. (2006). "Ontology of evolution and methodology of taxonomy". Paleontological Journal. 40 (S6): S679 – S737. Bibcode:2006PalJ...40S.679R. doi:10.1134/S003103010612001X. S2CID 15668901.

- ^ Schulmeister, S. (2003). "Simultaneous analysis of basal Hymenoptera (Insecta), introducing robust-choice sensitivity analysis". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 79 (2): 245–275. doi:10.1046/j.1095-8312.2003.00233.x.

- ^ Schulmeister, S. "Symphyta". Archived from the original on 21 June 2010. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ a b Capinera 2008, pp. 3250–3252.

- ^ Taeger, A.; Blank, S. M.; Liston, A. (2010). "World catalog of symphyta (Hymenoptera)". Zootaxa. 2580: 1–1064. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2580.1.1. ISSN 1175-5334.

- ^ Skvarla, M. J.; Smith, D. R.; Fisher, D. M.; Dowling, A. P. G. (2016). "Terrestrial arthropods of Steel Creek, Buffalo National River, Arkansas. II. Sawflies (Insecta: Hymenoptera: "Symphyta")". Biodiversity Data Journal. 4 (4) e8830. doi:10.3897/BDJ.4.e8830. PMC 4867044. PMID 27222635.

- ^ Taeger, A.; Blank, S. M. (1996). "Kommentare zur Taxonomie der Symphyta (Hymenoptera): Vorarbeiten zu einem Katalog der Pflanzenwespen, Teil 1". Beiträge zur Entomologie (in German). 46 (2): 251–275.

- ^ Rasnitsyn, A. P. (1988). "An outline of evolution of hymenopterous insects (order Vespida)". Oriental Insects. 22: 115–145. doi:10.1080/00305316.1988.11835485.

- ^ Dowton, M.; Austin, A. D. (1994). "Molecular phylogeny of the insect order Hymenoptera: apocritan relationships". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 91 (21): 9911–9915. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.9911D. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.21.9911. PMC 44927. PMID 7937916.

- ^ Goulet & Huber 1993, p. 104.

- ^ Goulet & Huber 1993, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Burton, M.; Burton, R. (2002). International Wildlife Encyclopedia. Vol. 16 (3rd ed.). Tarrytown, New York: Marshall Cavendish. pp. 2240–2241. ISBN 978-0-7614-7282-7.

- ^ a b Goulet & Huber 1993, p. 6.

- ^ Gao, T.; Shih, C.; Rasnitsyn, A.P.; Ren, D.; Laudet, V. (2013). "Hoplitolyda duolunica gen. et sp. nov. (Insecta, Hymenoptera, Praesiricidae), the hitherto largest sawfly from the Mesozoic of China". PLOS ONE. 8 (5) e62420. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...862420G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062420. PMC 3643952. PMID 23671596.

- ^ Benson, R.B. (1952). Handbooks for the Identification of British Insects: VI Hymenoptera 2 Symphyta Section (b) (PDF). London: Royal Entomological Society of London. p. 51. OCLC 429798429. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015.

- ^ Ross 1937, p. 11.

- ^ Ross 1937, p. 9.

- ^ a b Ross 1937, p. 10.

- ^ Ross 1937, p. 21.

- ^ Ross 1937, p. 13.

- ^ Ross 1937, pp. 22–29.

- ^ Ross 1937, p. 27.

- ^ Adams, C.; Early, M.; Brook, J.; Bamford, K. (2014). Principles of Horticulture: Level 2. New York, New York: Routledge. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-317-93777-7.

- ^ Ross 1937, p. 29.

- ^ Looney, C.; Smith, D.R; Collman, S.J.; Langor, D.W.; Peterson, M.A. (2016). "Sawflies (Hymenoptera, Symphyta) newly recorded from Washington State". Journal of Hymenoptera Research. 49: 129–159. doi:10.3897/JHR.49.7104.

- ^ Rosenthal, G.A.; Berenbaum, M.R. (1991). Herbivores: Their Interactions with Secondary Plant Metabolites (2nd ed.). Oxford: Elsevier Science. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-323-13940-3.

- ^ a b "Sawflies (Tenthredinoidae)". BBC. 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ^ Bandeili, B.; Müller, C. (2009). "Folivory versus florivory—adaptiveness of flower feeding". Naturwissenschaften. 97 (1): 79–88. Bibcode:2010NW.....97...79B. doi:10.1007/s00114-009-0615-9. PMID 19826770. S2CID 25877174.

- ^ a b Kleintjes, P.K.; Dahlsten, D.L. (1994). "Foraging behaviour and nestling diet of Chestnut-Backed chickadees in monterey pine" (PDF). The Condor. 96 (3): 647–653. doi:10.2307/1369468. JSTOR 1369468.

- ^ Cummins, S.; O'Halloran, J. (2002). "An assessment of the diet of nestling Stonechats using compositional analysis: Coleoptera (beetles), Hymenoptera (sawflies, ichneumon flies, bees, wasps and ants), terrestrial larvae (moth, sawfly and beetle) and Arachnida (spiders and harvestmen) accounted for 81% of Stonechat nestling diet". Bird Study. 49 (2): 139–145. doi:10.1080/00063650209461258. S2CID 86569805.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Phillips, C. (1992). "Spitfires – Defoliating Sawflies" (PDF). Department of Primary Industries and Resources. Government of South Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2015. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ^ Campbell, L.H.; Avery, M.I.; Donald, P.; Evans, A.D.; Green, R.E.; Wilson, J.D. (1997). A Review of the Indirect Effects of Pesticides on Birds (PDF) (Report). Peterborough, UK: Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Report. no 227. p. 27. ISSN 0963-8091. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ^ Brickle, N.W.; Harper, D.G.C. (1999). "Diet of nestling Corn Buntings Miliaria calandra in southern England examined by compositional analysis of faeces". Bird Study. 46 (3): 319–329. Bibcode:1999BirdS..46..319B. doi:10.1080/00063659909461145.

- ^ Starling-Westerberg, A. (2001). "The habitat use and diet of Black Grouse Tetrao tetrix in the Pennine hills of northern England". Bird Study. 48 (1): 76–89. Bibcode:2001BirdS..48...76S. doi:10.1080/00063650109461205.

- ^ Cayford, J.T. (1990). "Distribution and habitat preferences of Black Grouse in commercial forests in Wales: conservation and management implications". Proceedings of the International Union Game of Biologists Congress. 19: 435–447.

- ^ Holling, C.S. (1959). "The components of predation as revealed by a study of small-mammal predation of the European Pine Sawfly" (PDF). The Canadian Entomologist. 91 (5): 293–320. doi:10.4039/Ent91293-5. S2CID 53474917.

- ^ Müller, Caroline; Brakefield, P.M. (2003). "Analysis of a chemical defense in sawfly larvae: easy bleeding targets predatory wasps in late summer". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 29 (12): 2683–2694. Bibcode:2003JCEco..29.2683M. doi:10.1023/B:JOEC.0000008012.73092.01. ISSN 1573-1561. PMID 14969355. S2CID 23689052.

- ^ Petre, C.-A.; Detrain, C.; Boevé, J.-L. (2007). "Anti-predator defence mechanisms in sawfly larvae of Arge (Hymenoptera, Argidae)". Journal of Insect Physiology. 53 (7): 668–675. Bibcode:2007JInsP..53..668P. doi:10.1016/j.jinsphys.2007.04.007. hdl:2268/151323. PMID 17540402.

- ^ Phillips, Charlma (December 1992). "Spitfires - Defoliating Sawflies". PIRSA. Archived from the original on 6 November 2009. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- ^ Hairston, N.G. (1989). Ecological Experiments: Purpose, Design and Execution. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cambridge University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-521-34692-4.

- ^ a b c d e Capinera 2008, p. 1827.

- ^ Alberta Agriculture (1988). Guide to Crop Protection in Alberta. Vol. 2. Alberta: University of Alberta. p. 73.

- ^ Nelson, W.A.; Farstad, C.W. (2012). "Biology of Bracon cephi (Gahan) (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), an important native parasite of the wheat stem sawfly, Cephus cinctus Nort. (Hymenoptera: Cephidae), in Western Canada". The Canadian Entomologist. 85 (3): 103–107. doi:10.4039/Ent85103-3. S2CID 85132364.

- ^ Capinera 2008, p. 1827–1828.

- ^ a b Capinera 2008, p. 1828.

- ^ Morris, K.R.S.; Cameron, E.; Jepson, W.F. (1937). "The insect parasites of the spruce sawfly (Diprion polytomum, Htg.) in Europe". Bulletin of Entomological Research. 28 (3): 341–393. doi:10.1017/S0007485300038840.

- ^ Hartman, J.R.; Pirone, T.P.; Sall, M.A. (2000). Pirone's Tree Maintenance (7th ed.). New York, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 235. ISBN 978-0-19-802817-8.

- ^ Müller, C.; Barker, A.; Boevé, J.-L.; De Jong, P.W.; De Vos, H.; Brakefield, P.M. (2004). "Phylogeography of two parthenogenetic sawfly species (Hymenoptera: Tenthredinidae): relationship of population genetic differentiation to host plant distribution". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 83 (2): 219–227. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2004.00383.x.

- ^ Krokene, Paal (6 December 2014). "The common pine sawfly – a troublesome relative". Science Nordic. Archived from the original on 29 November 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ "Iris sawfly". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ "Large rose sawfly". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ "Great Wood Wasps". UK Safari. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ "Giant Woodwasp". Massachusetts Introduced Pests Outreach Project. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

Bibliography

[edit]- Capinera, J.L. (2008). Encyclopedia of Entomology (2nd ed.). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4020-6242-1.

- Goulet, H.; Huber, J.T. (1993). Hymenoptera of the World: An Identification guide to families (PDF). Ottawa, Ontario: Agriculture Canada. ISBN 978-0-660-14933-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016.

- Ross, H.H. (1937). A Generic Classification of the Nearctic Sawflies (Hymenoptera, Symphyta). Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.50339. hdl:2142/27324.

Further reading

[edit]- Blank, S.M.; Schmidt, S.; Taeger, A. (2006). Recent Sawfly Research Synthesis and Prospects. Keltern, Germany: Goecke und Evers. ISBN 978-3-937783-19-2.

- Schedl, Wolfgang. (2016). Hymenoptera, Unterordnung Symphyta: Pflanzenwespen. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-085790-0.

- Smith, D.R. (1969). Nearctic Sawflies I. Blennocampinae: Adults and Larvae (Hymenoptera: Tenthredinidae) (Technical Bulletin 1397). Washington, D.C.: US Department of Agriculture.

- Smith, D.R. (1969). Nearctic Sawflies II. Selandriinae: Adults and Larvae (Hymenoptera: Tenthredinidae) (Technical Bulletin 1398). Washington, D.C.: US Department of Agriculture.

- Smith, D.R. (1971). Nearctic Sawflies III. Heterarthrinae: Adults and Larvae (Hymenoptera: Tenthredinidae) (Technical Bulletin 1420). Washington, D.C.: US Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- Smith, D.R. (1979). Nearctic Sawflies IV. Allantinae: Adults and Larvae (Hymenoptera: Tenthredinidae) (Technical Bulletin 1595). Washington, D.C.: US Department of Agriculture.

- Wagner, M.R.; Raffa, K.F. (1993). Sawfly Life History Adaptations to Woody Plants. San Diego, California: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-730030-6.

External links

[edit]General

[edit]- Symphyta: Encyclopædia Britannica

- Sawflies: a close relative of wasps at CSIRO

- Symphyta" - Sawflies, Horntails, and Wood Wasps at BugGuide

Taxonomy

[edit]- Taxonomy of Hymenoptera – Chrysis.net

- ECatSym - Electronic World Catalog of Symphyta (Insecta, Hymenoptera) – Digital Entomological Information

- Checklist of British and Irish Hymenoptera - Sawflies, 'Symphyta' Biodiversity Data Journal 2: e1168