Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sigma Orionis

View on Wikipedia| Observation data Epoch J2000 Equinox J2000 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Orion |

| Right ascension | 05h 38m 42.0s[1] |

| Declination | −02° 36′ 00″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | A: 4.07[2] B: 5.27 C: 8.79 D: 6.62 E: 6.66 (6.61 - 6.77[3]) |

| Characteristics | |

| AB | |

| Spectral type | O9.5V + B0.5V[4] |

| U−B color index | −1.02[5] |

| B−V color index | −0.31[5] |

| C | |

| Spectral type | A2 V[6] |

| U−B color index | −0.25[7] |

| B−V color index | −0.02[7] |

| D | |

| Spectral type | B2 V[6] |

| U−B color index | −0.87[8] |

| B−V color index | −0.17[8] |

| E | |

| Spectral type | B2 Vpe[9] |

| U−B color index | −0.84[10] |

| B−V color index | −0.09[10] |

| Variable type | SX Ari[3] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −29.45 ± 0.45[11] km/s |

| Parallax (π) | AB: 3.04 ± 8.92[12] mas D: 6.38 ± 0.90 mas[12] |

| Distance | 387.51 ± 1.32[13] pc |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | −3.49 (Aa) −2.90 (Ab) −2.79 (B)[14] |

| Orbit[13] | |

| Primary | Aa |

| Companion | Ab |

| Period (P) | 143.2002 ± 0.0024 days |

| Semi-major axis (a) | 0.0042860" (~360 R☉[15]) |

| Eccentricity (e) | 0.77896 ± 0.00043 |

| Inclination (i) | ~56.378 ± 0.085° |

| Semi-amplitude (K1) (primary) | 72.03 ± 0.25 km/s |

| Semi-amplitude (K2) (secondary) | 95.53 ± 0.22 km/s |

| Orbit[13] | |

| Primary | A |

| Companion | B |

| Period (P) | 159.896 ± 0.005 yr |

| Semi-major axis (a) | 0.2629 ± 0.0022″ |

| Eccentricity (e) | 0.024 ± 0.005 |

| Inclination (i) | 172.1 ± 4.6° |

| Details[14] | |

| σ Ori Aa | |

| Mass | 18 M☉ |

| Radius | 5.6 R☉ |

| Luminosity | 41,700 L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.20 cgs |

| Temperature | 35,000 K |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 135 km/s |

| Age | 0.3 Myr |

| σ Ori Ab | |

| Mass | 13 M☉ |

| Radius | 4.8 R☉ |

| Luminosity | 18,600 L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.20 cgs |

| Temperature | 31,000 K |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 35 km/s |

| Age | 0.9 Myr |

| σ Ori B | |

| Mass | 14 M☉ |

| Radius | 5.0 R☉ |

| Luminosity | 15,800 L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.15 cgs |

| Temperature | 29,000 K |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 250 km/s |

| Age | 1.9 Myr |

| Details[6] | |

| C | |

| Mass | 2.7 M☉ |

| Details[16] | |

| D | |

| Mass | 6.8 M☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.3 cgs |

| Temperature | 21,500 K |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 180 km/s |

| Details | |

| E | |

| Mass | 8.30[9] M☉ |

| Radius | 3.77[9] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 3,162[17] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.2±0.2[17] cgs |

| Temperature | 22,500[9] K |

| Rotation | 1.190847 days[9] |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 140±10[17] km/s |

| Age | 0.4-0.9[17] Myr |

| Other designations | |

| Sigma Orionis, Sigma Ori, σ Orionis, σ Ori, 48 Orionis, 48 Ori | |

| AB: HD 37468, HR 1931, HIP 26549, SAO 132406, BD−02°1326, 2MASS J05384476-0236001, Mayrit AB | |

| C: 2MASS J05384411-0236062, Mayrit 11238 | |

| D: HIP 26551, 2MASS J05384561-0235588, Mayrit 13084 | |

| E: V1030 Orionis, HR 1932, HD 37479, BD−02°1327, 2MASS J05384719-0235405, Mayrit 41062 | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | σ Ori |

| σ Ori C | |

| σ Ori D | |

| σ Ori E | |

| σ Ori Cluster | |

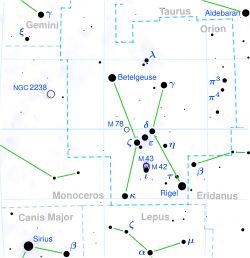

Sigma Orionis or Sigma Ori (σ Orionis, σ Ori) is a multiple star system in the constellation Orion, consisting of the brightest members of a young open cluster. It is found at the eastern end of the belt, south west of Alnitak and west of the Horsehead Nebula which it partially illuminates. The combined brightness of the component stars is magnitude 3.80.

History

[edit]

σ Orionis is a naked eye star at the eastern end of Orion's Belt, and has been known since antiquity, but it was not included in Ptolemy's Almagest.[18] It was referred to by Al Sufi, but not formally listed in his catalogue.[19] In more modern times, it was measured by Tycho Brahe and included in his catalogue. In Kepler's extension it is described as "Quae ultimam baltei praecedit ad austr." (preceding the outermost of the belt, to the south).[20] It was then recorded by Johann Bayer in his Uranometria as a single star with the Greek letter σ (sigma). He described it as "in enſe, prima" (in the sword, first).[21] It was also given the Flamsteed designation 48.

In 1776, Christian Mayer described σ Ori as a triple star, having seen components AB and E, and suspected another between the two. Component D was confirmed by FGW Struve who also added a fourth (C), published in 1876. In 1892 Sherburne Wesley Burnham reported that σ Ori A was itself a very close double, although a number of later observers failed to confirm it. In the second half of the twentieth century, the orbit of σ Ori A/B was solved and at the time was one of the most massive binaries known.[22]

σ Ori A was discovered to have a variable radial velocity in 1904, considered to indicate a single-lined spectroscopic binary.[23] The spectral lines of the secondary were elusive and often not seen at all, possibly because they are broadened by rapid rotation. There was confusion over whether the reported spectroscopic binary status actually referred to the known visual companion B. Finally in 2011, it was confirmed that the system is triple, with an inner spectroscopic pair and a wider visual companion.[22] The inner pair was resolved interferometrically in 2013.[15]

σ Ori E was identified as helium-rich in 1956,[7] having variable radial velocity in 1959,[24] having variable emission features in 1974,[25] having an abnormally strong magnetic field in 1978,[26] being photometrically variable in 1977,[27] and formally classified as a variable star in 1979.[28]

In 1996, a large number of low-mass pre-main sequence stars were identified in the region of Orion's Belt.[29] A particular close grouping was discovered to lie around σ Orionis.[30] A large number of brown dwarfs were found in the same area and at the same distance as the bright σ Orionis stars.[31] Optical, infrared, and x-ray objects in the cluster, including 115 non-members lying in the same direction, were listed in the Mayrit Catalogue with a running number, except for the central star which was listed simply as Mayrit AB.[32]

Cluster

[edit]

HD 294268, F6e, probable member

HD 294275, A0

HD 294297, G0

HD 294300, G5 T Tauri star

HD 294301, A5

The σ Orionis cluster is part of the Ori OB1b stellar association, commonly referred to as Orion's Belt. The cluster was not recognised until 1996 when a population of pre-main sequence stars was discovered around σ Ori. Since then it has been extensively studied because of its closeness and the lack of interstellar extinction. It has been calculated that star formation in the cluster began 3 million years (myr) ago and it is approximately 360 pc away.[6]

In the central arc-minute of the cluster five particularly bright stars are visible, labelled A to E in order of distance from the brightest component σ Ori A. The closest pair AB are only separated by 0.2" - 0.3" but were discovered with a 12" telescope.[33] An infrared and radio source, IRS1, 3.3" from σ Ori A that was considered to be a patch of nebulosity has been resolved into two subsolar stars. There is an associated variable x-ray source that is assumed to be a T Tauri star.[34]

The cluster is considered to include a number of other stars of spectral class A or B:[6][35]

- HD 37699, an outlying B5 giant very close to the Horsehead Nebula

- HD 37525, a B5 main sequence star and spectroscopic binary

- HD 294271, a B5 young stellar object with two low mass companions

- HD 294272, a binary containing two B class young stellar objects

- HD 37333, a peculiar A1 main sequence star

- HD 37564, an A8 young stellar object

- V1147 Ori, a B9.5 giant and α2 CVn variable

- HD 37686, a B9.5 main sequence star close to HD 37699

- HD 37545, an outlying B9 main sequence

- HD 294273, an A8 young stellar object

- 2MASS J05374178-0229081, an A9 young stellar object

HD 294271 and HD 294272 make up the "double" star Struve 761 (or STF 761). It is three arc minutes from σ Orionis, which is also known as Struve 762.[36]

Over 30 other probable cluster members have been detected within an arc minute of the central star, mostly brown dwarfs and planetary mass objects such as S Ori 60,[37] but including the early M red dwarfs 2MASS J05384746-0235252 and 2MASS J05384301-0236145.[34] In total, several hundred low mass objects are thought to be cluster members, including around a hundred spectroscopically measured class M stars, around 40 K class stars, and a handful of G and F class objects. Many are grouped in a central core, but there is a halo of associated objects scattered across more than 10 arc-minutes.[35] The cluster includes a few L-dwarfs, which are determined to be planetary mass objects.[38] In the past a few T-dwarfs were thought to be part of the cluster, but so far most of these T-dwarfs turned out to be brown dwarfs in the foreground.[39] Some of these L-dwarfs (around 29%) are surrounded by a dusty disk.[40] The cluster also contains a pair consisting out of the brown dwarf SE 70 and the planetary-mass object S Ori 68, which are separated by 1700 astronomical units.[41] In 2024 high-resolution imaging with ALMA of K-stars and early M-stars showed gaps and rings in the disks around these stars. One star called Haro 5-34 (SO 1274, K7-type star) showed five gaps, seemingly arranged in a resonant chain. The disks in the cluster are small, either due to external photoevaporation by σ Orionis or the intermediate age of the region.[42]

σ Orionis AB

[edit]The brightest member of the σ Orionis system appears as a late O class star, but is actually made up of three stars, designated Aa, Ab, and B. The inner pair complete a highly eccentric orbit every 143 days, while the outer star completes its near-circular orbit once every 157 years. It has not yet completed a full orbit since it was first discovered to be a double star. All three are very young main sequence stars with masses between 11 and 18 M☉.

Components

[edit]

The primary component Aa is the class O9.5 star, with a temperature of 35,000 K and a luminosity over 40,000 L☉. Lines representing a B0.5 main sequence star have been shown to belong to its close companion Ab, which has a temperature of 31,000 K and a luminosity of 18,600 L☉. Their separation varies from less than half an astronomical unit to around two AU. Although they cannot be directly imaged with conventional single mirror telescopes, their respective visual magnitudes have been calculated at 4.61 and 5.20.[14] The two components of σ Orionis A have been resolved interferometrically using the CHARA array, and the combination of interferometric and visual observations yields a very accurate orbit.[13]

The spectrum of component B, the outer star of the triple, cannot be detected. The luminosity contribution from σ Ori B can be measured and it is likely to be a B0-2 main sequence star. Its visual magnitude of 5.31 is similar to σ Ori Ab and so it should be easily visible, but it is speculated that its spectral lines are highly broadened and invisible against the backdrop of the other two stars.[14] The orbit of component B has been calculated precisely using the NPOI and CHARA arrays. The combined orbits of the three stars together give a parallax significantly more precise than the HIPPARCOS parallax.[13]

The inclinations of the two orbits are known accurately enough to calculate their relative inclination. The two orbital planes are within 30° of being orthogonal, with the inner orbit being prograde and the outer retrograde. Although slightly surprising, this situation is not necessarily rare in triple systems.[13]

Mass discrepancy

[edit]The masses of these three component stars can be calculated using: spectroscopic calculation of the surface gravity and hence a spectroscopic mass; comparison of evolutionary models to the observed physical properties to determine an evolutionary mass as well as the age of the stars; or determination of a dynamical mass from the orbital motions of the stars. The spectroscopic masses found for each component of σ Orionis have large margins of error, but the dynamical and spectroscopic masses are considered accurate to about one M☉, and the dynamical masses of the two components of σ Orionis A are known to within about a quarter M☉. However, the dynamical masses are all larger than the evolutionary masses by more than their margins of error, indicating a systemic problem.[14][13] This type of mass discrepancy is a common and long-standing problem found in many stars.[43]

Ages

[edit]Comparison of the observed or calculated physical properties of each star with theoretical stellar evolutionary tracks allows the age of the star to be estimated. The estimated ages of the components Aa, Ab, and B, are respectively 0.3+1.0

−0.3 Myr, 0.9+1.5

−0.9 Myr, and 1.9+1.6

−1.9 Myr. Within their large margins of error, these can all be considered to be consistent with each other, although it is harder to reconcile them with the 2-3 Myr estimated age of the σ Orionis cluster as a whole.[13]

σ Orionis C

[edit]The faintest member of the main σ Orionis stars is component C. It is also the closest to σ Ori AB at 11", corresponding to 3,960 astronomical units. It is an A-type main sequence star. σ Ori C has a faint companion 2" away, referred to as Cb[44] and MAD-4.[34] Cb is five magnitudes fainter than σ Ori Ca at infrared wavelengths, K band magnitude 14.07, and is likely to be a brown dwarf.[34]

σ Orionis D

[edit]Component D is a fairly typical B2 main sequence star of magnitude 6.62. It is 13" from σ Ori AB, corresponding to 4,680 AU. Its size, temperature, and brightness are very similar to σ Ori E but it shows none of the unusual spectral features or variability of that star.

σ Orionis E

[edit]

Component E is an unusual variable star, classified as an SX Arietis variable and also known as V1030 Orionis. It is helium-rich, has a strong magnetic field, and varies between magnitudes 6.61 and 6.77 during a 1.19 day period of rotation. It has a spectral type of B2 Vpe. The variability is believed to be due to large-scale variations in surface brightness caused by the magnetic field. The rotational period is slowing due to magnetic braking;[9] it is one of the few magnetic stars to have its rotation period change directly measured.[17] σ Ori E is 41" from σ Ori AB, approximately 15,000 AU.[2]

The magnetic field is highly variable from −2,300 to +3,100 gauss, matching the brightness variations and the likely rotational period. This requires a magnetic dipole of at least 10,000 G. Around minimum brightness, a shell type spectrum appears, attributed to plasma clouds rotating above the photosphere. The helium enhancement in the spectrum may be due to hydrogen being preferentially trapped towards the magnetic poles leaving excess helium near the equator.[26] It was at one point suggested that σ Ori E could be further away and older than the other members of the cluster, from modelling its evolutionary age and size.[16] However, Gaia parallaxes place σ Ori E within the cluster, and later modelling has suggested that it is very young, at less than a million years old.[17]

σ Ori E has a faint companion about a third of an arc-second away. It is about 5 magnitudes fainter than the helium-rich primary, about magnitude 10-11 at K band infrared wavelengths. It is presumed to be a low mass star 0.4 - 0.8 M☉.[34]

σ Orionis IRS1

[edit]The infrared source IRS1 is close to σ Ori A. It has been resolved to a pair of low mass objects, a proplyd, and a possible third object. The brighter object has an M1 spectral class, a mass around a half M☉, and appears to be a relatively normal low mass star. The fainter object is very unusual, showing a diluted M7 or M8 absorption spectrum with emission lines of hydrogen and helium. The interpretation is that it is a brown dwarf embedded within a proplyd that is being photoevaporated by σ Ori A. X-ray emission from IRS1 suggests the presence of an accretion disc around a T Tauri star, but it is unclear how this can fit with the proplyd scenario.[46]

Dust wave

[edit]

In infrared images, a prominent arc is visible centred on σ Ori AB. It is about 50" away from the class O star, around 0.1 parsecs at its distance. It is directed towards IC434, the Horesehead Nebula, in line with the space motion of the star. The appearance is similar to a bowshock, but the type of radiation shows that it is not a bowshock. The observed infrared emission, peaking at around 45 microns, can be modelled by two approximately black-body components, one at 68K and one at 197 K. These are thought to be produced by two different sizes of dust grains.

The material of the arc is theorised to be produced by photoevaporation from the molecular cloud around the Horsehead Nebula. The dust becomes decoupled from the gas that carried it away from the molecular cloud by radiation pressure from the hot stars at the centre of the σ Orionis cluster. The dust accumulates into a denser region that is heated and forms the visible infrared shape.

The term "dust wave" is applied when the dust piles up but the gas is largely unaffected, as opposed to a "bow wave" where both dust and gas are stopped. Dust waves occur when the interstellar medium is sufficiently dense and the stellar wind sufficiently weak that the dust stand-off distance is larger than the stand-off distance of a bow shock. This would clearly be more likely for slow-moving stars, but slow-moving luminous stars may not have lifetimes long enough to produce a bow wave. Low luminosity late class O stars should commonly produce bow waves if this model is correct.[47]

Another study does however find that this feature is due σ Ori AB being a runaway star. Evidence for the runaway nature of the star are a different proper motion compared to the cluster, an infrared arc along the predicted velocity vector and a disparity in protoplanetary disk masses inside the cluster. The disks yet to encounter σ Ori AB have a higher disk mass, than those already encountered σ Ori AB. The disks already encountered have a reduced disk mass due to photoevaporation by the powerful radiation by σ Ori AB. This result needs confirmation by better constraining the proper motion of σ Ori AB.[48]

Distance

[edit]The distance to σ Orionis and the cluster of stars around it has historically been uncertain. Hipparcos parallaxes were available for several presumed members, but with very high uncertainties for the σ Orionis components. Published distance estimates ranged from 352 pc to 473 pc.[17] A dynamical parallax of 2.5806±0.0088 mas has been derived using the orbits of the two central stars, giving a distance of 387.5±1.3 pc.[13]

Gaia has published parallaxes for hundreds of cluster members, including brown dwarfs, and thousands of other stars in the field of the cluster. The cluster has been found to be quite extended, but around an average distance of 391+50

−40 pc.[17] Gaia Data Release 3 parallaxes for components C, D, and E are 2.4720±0.0293 mas,[49] 2.4744±0.0622 mas,[50] and 2.3077±0.0647 mas respectively.[51] These have low statistical uncertainties although significant astrometric excess noise. No Gaia parallax has been published for the central AB component. Corresponding distances are 402±4 pc, 401±9 pc, and 428±12 pc for components C, D, and E respectively.[52]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Wu, Zhen-Yu; Zhou, Xu; Ma, Jun; Du, Cui-Hua (2009). "The orbits of open clusters in the Galaxy". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 399 (4): 2146. arXiv:0909.3737. Bibcode:2009MNRAS.399.2146W. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.15416.x. S2CID 6066790.

- ^ a b Mason, Brian D.; Wycoff, Gary L.; Hartkopf, William I.; Douglass, Geoffrey G.; Worley, Charles E. (2001). "The 2001 US Naval Observatory Double Star CD-ROM. I. The Washington Double Star Catalog". The Astronomical Journal. 122 (6): 3466. Bibcode:2001AJ....122.3466M. doi:10.1086/323920.

- ^ a b Samus, N. N.; Durlevich, O. V.; et al. (2009). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: General Catalogue of Variable Stars (Samus+ 2007-2013)". VizieR On-line Data Catalog: B/GCVS. Originally Published in: 2009yCat....102025S. 1. Bibcode:2009yCat....102025S.

- ^ Caballero, J. A. (2014). "Stellar multiplicity in the sigma Orionis cluster: A review". The Observatory. 134: 273. arXiv:1408.2231. Bibcode:2014Obs...134..273C.

- ^ a b Echevarria, J.; Roth, M.; Warman, J. (1979). "Photometric Study of Trapezium-Type Systems". Revista Mexicana de Astronomía y Astrofísica. 4: 287. Bibcode:1979RMxAA...4..287E.

- ^ a b c d e Caballero, J. A. (2007). "The brightest stars of the σ Orionis cluster". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 466 (3): 917–930. arXiv:astro-ph/0701067. Bibcode:2007A&A...466..917C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20066652. S2CID 14991312.

- ^ a b c Greenstein, Jesse L.; Wallerstein, George (1958). "The Helium-Rich Star, Sigma Orionis E". Astrophysical Journal. 127: 237. Bibcode:1958ApJ...127..237G. doi:10.1086/146456.

- ^ a b Guetter, H. H. (1979). "Photometric studies of stars in ORI OB1 /belt/". Astronomical Journal. 84: 1846. Bibcode:1979AJ.....84.1846G. doi:10.1086/112616.

- ^ a b c d e f Townsend, R. H. D.; Rivinius, Th.; Rowe, J. F.; Moffat, A. F. J.; Matthews, J. M.; Bohlender, D.; Neiner, C.; Telting, J. H.; Guenther, D. B.; Kallinger, T.; Kuschnig, R.; Rucinski, S. M.; Sasselov, D.; Weiss, W. W. (2013). "MOST Observations of σ Ori E: Challenging the Centrifugal Breakout Narrative". The Astrophysical Journal. 769 (1): 33. arXiv:1304.2392. Bibcode:2013ApJ...769...33T. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/769/1/33. S2CID 39402058.

- ^ a b Ducati, J. R. (2002). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: Catalogue of Stellar Photometry in Johnson's 11-color system". CDS/ADC Collection of Electronic Catalogues. 2237. Bibcode:2002yCat.2237....0D.

- ^ Kharchenko, N. V.; Scholz, R.-D.; Piskunov, A. E.; Röser, S.; Schilbach, E. (2007). "Astrophysical supplements to the ASCC-2.5: Ia. Radial velocities of ˜55000 stars and mean radial velocities of 516 Galactic open clusters and associations". Astronomische Nachrichten. 328 (9): 889. arXiv:0705.0878. Bibcode:2007AN....328..889K. doi:10.1002/asna.200710776. S2CID 119323941.

- ^ a b Van Leeuwen, F. (2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–664. arXiv:0708.1752. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. S2CID 18759600.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Schaefer, G. H.; Hummel, C. A.; Gies, D. R.; Zavala, R. T.; Monnier, J. D.; Walter, F. M.; Turner, N. H.; Baron, F.; ten Brummelaar, T. (2016-12-01). "Orbits, Distance, and Stellar Masses of the Massive Triple Star sigma Orionis". The Astronomical Journal. 152 (6): 213. arXiv:1610.01984. Bibcode:2016AJ....152..213S. doi:10.3847/0004-6256/152/6/213. ISSN 0004-6256. S2CID 36047128.

- ^ a b c d e Simón-Díaz, S.; Caballero, J. A.; Lorenzo, J.; Maíz Apellániz, J.; Schneider, F. R. N.; Negueruela, I.; Barbá, R. H.; Dorda, R.; Marco, A.; Montes, D.; Pellerin, A.; Sanchez-Bermudez, J.; Sódor, Á.; Sota, A. (2015). "Orbital and Physical Properties of the σ Ori Aa, Ab, B Triple System". The Astrophysical Journal. 799 (2): 169. arXiv:1412.3469. Bibcode:2015ApJ...799..169S. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/799/2/169. S2CID 118500350.

- ^ a b Hummel, C. A.; Zavala, R. T.; Sanborn, J. (2013). "Binary Studies with the Navy Precision Optical Interferometer". Central European Astrophysical Bulletin. 37: 127. Bibcode:2013CEAB...37..127H.

- ^ a b Hunger, K.; Heber, U.; Groote, D. (1989). "The distance of the helium-variable B star HD 37479". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 224: 57. Bibcode:1989A&A...224...57H.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Song, H. F.; Meynet, G.; Maeder, A.; Mowlavi, N.; Stroud, S. R.; Keszthelyi, Z.; Ekström, S.; Eggenberger, P.; Georgy, C.; Wade, G. A.; Qin, Y. (2022). "News from Gaia on σ Ori E: A case study for the wind magnetic braking process". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 657: A60. arXiv:2108.13734. Bibcode:2022A&A...657A..60S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202141512. S2CID 237363358.

- ^ The Almagest. Encyclopædia Britannica. 1990. ISBN 978-0-85229-531-1.

- ^ Hafez, Ihsan; Stephenson, F. Richard; Orchiston, Wayne (2011). "Abdul-Rahan al-Şūfī and His Book of the Fixed Stars: A Journey of Re-discovery". Highlighting the History of Astronomy in the Asia-Pacific Region. Astrophysics and Space Science Proceedings. Vol. 23. pp. 121–138. Bibcode:2011ASSP...23..121H. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-8161-5_7. ISBN 978-1-4419-8160-8.

- ^ Verbunt, F.; Van Gent, R. H. (2010). "Three editions of the star catalogue of Tycho Brahe. Machine-readable versions and comparison with the modern Hipparcos Catalogue". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 516: A28. arXiv:1003.3836. Bibcode:2010A&A...516A..28V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201014002. S2CID 54025412.

- ^ Johann Bayer (1987). Uranometria. Aldbrough St John Publications. ISBN 978-1-85297-021-5.

- ^ a b Simón-Díaz, S.; Caballero, J. A.; Lorenzo, J. (2011). "A Third Massive Star Component in the σ Orionis AB System". The Astrophysical Journal. 742 (1): 55. arXiv:1108.4622. Bibcode:2011ApJ...742...55S. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/742/1/55. S2CID 118383283.

- ^ Frost, E. B.; Adams, W. S. (1904). "Eight stars whose radial velocities vary". Astrophysical Journal. 19: 151. Bibcode:1904ApJ....19..151F. doi:10.1086/141098.

- ^ Wallerstein, George (1959). "The Radial Velocity of Sigma Orionis". Astrophysical Journal. 130: 338. Bibcode:1959ApJ...130..338W. doi:10.1086/146722.

- ^ Walborn, Nolan R. (1974). "A New Phenomenon in the Spectrum of Sigma Orionis E". Astrophysical Journal. 191: L95. Bibcode:1974ApJ...191L..95W. doi:10.1086/181558.

- ^ a b Landstreet, J. D.; Borra, E. F. (1978). "The magnetic field of Sigma Orionis E". Astrophysical Journal. 224: L5. Bibcode:1978ApJ...224L...5L. doi:10.1086/182746.

- ^ Warren, W. H.; Hesser, J. E. (1977). "A photometric study of the Orion OB 1 association. I - Observational data". Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 34: 115. Bibcode:1977ApJS...34..115W. doi:10.1086/190446.

- ^ Kholopov, P. N.; Kukarkina, N. P.; Perova, N. B. (1979). "64th Name-List of Variable Stars". Information Bulletin on Variable Stars. 1581: 1. Bibcode:1979IBVS.1581....1K.

- ^ Wolk, Scott J. (1996). Watching the Stars go 'Round and 'Round (Thesis). Bibcode:1996PhDT........63W.

- ^ Walter, F. M.; Wolk, S. J.; Freyberg, M.; Schmitt, J. H. M. M. (1997). "Discovery of the σ Orionis Cluster". Memorie della Società Astronomia Italiana. 68: 1081. Bibcode:1997MmSAI..68.1081W.

- ^ Béjar, V. J. S.; Osorio, M. R. Zapatero; Rebolo, R. (1999). "A Search for Very Low Mass Stars and Brown Dwarfs in the Young σ Orionis Cluster". The Astrophysical Journal. 521 (2): 671. arXiv:astro-ph/9903217. Bibcode:1999ApJ...521..671B. doi:10.1086/307583. S2CID 119366292.

- ^ Caballero, J. A. (2008). "Stars and brown dwarfs in the σ Orionis cluster: The Mayrit catalogue". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 478 (2): 667–674. arXiv:0710.5882. Bibcode:2008A&A...478..667C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20077885. S2CID 118592865.

- ^ Burnham, S. W. (1894). "Fourteenth Catalogue of New Double Stars Discovered at the Lick Observatory". Publications of Lick Observatory. 2: 185. Bibcode:1894PLicO...2..185B.

- ^ a b c d e Bouy, H.; Huélamo, N.; Martín, Eduardo L.; Marchis, F.; Barrado y Navascués, D.; Kolb, J.; Marchetti, E.; Petr-Gotzens, M. G.; Sterzik, M.; Ivanov, V. D.; Köhler, R.; Nürnberger, D. (2009). "A deep look into the cores of young clusters. I. σ-Orionis". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 493 (3): 931. arXiv:0808.3890. Bibcode:2009A&A...493..931B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200810267. S2CID 119113932.

- ^ a b Hernández, Jesús; Calvet, Nuria; Perez, Alice; Briceño, Cesar; Olguin, Lorenzo; Contreras, Maria E.; Hartmann, Lee; Allen, Lori; Espaillat, Catherine; Hernan, Ramírez (2014). "A Spectroscopic Census in Young Stellar Regions: The σ Orionis Cluster". The Astrophysical Journal. 794 (1): 36. arXiv:1408.0225. Bibcode:2014ApJ...794...36H. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/794/1/36. S2CID 118624280.

- ^ Struve, Friedrich Georg Wilhelm; Copeland, Ralph; Lindsay, James Ludovic (1876). "Struves (Revised) Table". Dun Echt Observatory Publications. 1: 1. Bibcode:1876PODE....1....1S.

- ^ Caballero, J. A.; Béjar, V. J. S.; Rebolo, R.; Eislöffel, J.; Zapatero Osorio, M. R.; Mundt, R.; Barrado Y Navascués, D.; Bihain, G.; Bailer-Jones, C. A. L.; Forveille, T.; Martín, E. L. (2007-08-01). "The substellar mass function in σ Orionis. II. Optical, near-infrared and IRAC/Spitzer photometry of young cluster brown dwarfs and planetary-mass objects". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 470 (3): 903–918. arXiv:0705.0922. Bibcode:2007A&A...470..903C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20066993. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ Barrado y Navascués, D.; Zapatero Osorio, M. R.; Béjar, V. J. S.; Rebolo, R.; Martín, E. L.; Mundt, R.; Bailer-Jones, C. A. L. (2001-10-01). "Optical spectroscopy of isolated planetary mass objects in the σ Orionis cluster". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 377: L9 – L13. arXiv:astro-ph/0108249. Bibcode:2001A&A...377L...9B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20011152. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ Peña Ramírez, K.; Zapatero Osorio, M. R.; Béjar, V. J. S. (2015-02-01). "Characterization of the known T-type dwarfs towards the σ Orionis cluster". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 574: A118. arXiv:1411.3370. Bibcode:2015A&A...574A.118P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201424816. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ Scholz, Alexander; Jayawardhana, Ray (2008-01-01). "Dusty Disks at the Bottom of the Initial Mass Function". The Astrophysical Journal. 672 (1): L49 – L52. arXiv:0711.2510. Bibcode:2008ApJ...672L..49S. doi:10.1086/526340. hdl:10023/4050. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Caballero, J. A.; Martín, E. L.; Dobbie, P. D.; Barrado Y Navascués, D. (2006-12-01). "Are isolated planetary-mass objects really isolated?. A brown dwarf-exoplanet system candidate in the σ Orionis cluster". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 460 (2): 635–640. arXiv:astro-ph/0608659. Bibcode:2006A&A...460..635C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20066162. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ Huang, Jane; Ansdell, Megan; Birnstiel, Tilman; Czekala, Ian; Long, Feng; Williams, Jonathan; Zhang, Shangjia; Zhu, Zhaohuan (4 Oct 2024). "High Resolution ALMA Observations of Richly Structured Protoplanetary Disks in σ Orionis". The Astrophysical Journal. 976 (1): 132. arXiv:2410.03823. Bibcode:2024ApJ...976..132H. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ad84df.

- ^ Marconi, M.; Molinaro, R.; Bono, G.; Pietrzyński, G.; Gieren, W.; Pilecki, B.; Stellingwerf, R. F.; Graczyk, D.; Smolec, R.; Konorski, P.; Suchomska, K.; Górski, M.; Karczmarek, P. (2013). "The Eclipsing Binary Cepheid OGLE-LMC-CEP-0227 in the Large Magellanic Cloud: Pulsation Modeling of Light and Radial Velocity Curves". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 768 (1): L6. arXiv:1304.0860. Bibcode:2013ApJ...768L...6M. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/768/1/L6. S2CID 119194645.

- ^ Caballero, J. A. (2005). "Ultra low-mass star and substellar formation in σ Orionis". Astronomische Nachrichten. 326 (10): 1007–1010. arXiv:astro-ph/0511166. Bibcode:2005AN....326.1007C. doi:10.1002/asna.200510468. S2CID 16515794.

- ^ "MAST: Barbara A. Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes". Space Telescope Science Institute. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- ^ Hodapp, Klaus W.; Iserlohe, Christof; Stecklum, Bringfried; Krabbe, Alfred (2009). "σ Orionis IRS1 a and B: A Binary Containing a Proplyd". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 701 (2): L100. arXiv:0907.3327. Bibcode:2009ApJ...701L.100H. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/701/2/L100. S2CID 18151435.

- ^ Ochsendorf, B. B.; Cox, N. L. J.; Krijt, S.; Salgado, F.; Berné, O.; Bernard, J. P.; Kaper, L.; Tielens, A. G. G. M. (2014). "Blowing in the wind: The dust wave around σ Orionis AB". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 563: A65. arXiv:1401.7185. Bibcode:2014A&A...563A..65O. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201322873. S2CID 59022322.

- ^ Coleman, Gavin A. L.; Haworth, Thomas J.; Jinyoung Serena Kim (2025). "Runaway origins of a disc mass gradient in σ Orionis". arXiv:2509.20227 [astro-ph.EP].

- ^ Vallenari, A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (2023). "Gaia Data Release 3. Summary of the content and survey properties". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 674: A1. arXiv:2208.00211. Bibcode:2023A&A...674A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202243940. S2CID 244398875. Gaia DR3 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ Vallenari, A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (2023). "Gaia Data Release 3. Summary of the content and survey properties". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 674: A1. arXiv:2208.00211. Bibcode:2023A&A...674A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202243940. S2CID 244398875. Gaia DR3 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ Vallenari, A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (2023). "Gaia Data Release 3. Summary of the content and survey properties". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 674: A1. arXiv:2208.00211. Bibcode:2023A&A...674A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202243940. S2CID 244398875. Gaia DR3 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ Bailer-Jones, C. A. L.; Rybizki, J.; Fouesneau, M.; Demleitner, M.; Andrae, R. (2021). "Estimating Distances from Parallaxes. V. Geometric and Photogeometric Distances to 1.47 Billion Stars in Gaia Early Data Release 3". The Astronomical Journal. 161 (3): 147. arXiv:2012.05220. Bibcode:2021AJ....161..147B. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/abd806. S2CID 228063812.

External links

[edit]- Turn Left at Orion Naked eye and telescopic views

- σ Orionis Archived 2016-04-15 at the Wayback Machine Researchers page at Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía

- January double star Observing guide from Astronomical Society of Southern Africa

- Bright and Multiple Stars Gallery taken at Fresno State's Campus Observatory, largely by students

- A Quintuple Star in the Constellation Orion for simpler explanation and pictures