Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Metalsmith

View on Wikipedia

A metalsmith or simply smith is a craftsperson fashioning useful items (for example, tools, kitchenware, tableware, jewelry, armor and weapons) out of various metals.[1] Smithing is one of the oldest metalworking occupations. Shaping metal with a hammer (forging) is the archetypical component of smithing. Often the hammering is done while the metal is hot, having been heated in a forge. Smithing can also involve the other aspects of metalworking, such as refining metals from their ores (traditionally done by smelting), casting it into shapes (founding), and filing to shape and size.

The prevalence of metalworking in the culture of recent centuries has led Smith and its equivalents in various languages to be a common occupational surname (German Schmidt or Schmied, Portuguese Ferreiro, Ferreira, French Lefèvre, Spanish Herrero, Italian Fabbri, Ferrari, Ferrero, Ukrainian Koval etc.). As a suffix, -smith connotes the meaning of a specialized craftsperson—for example, wordsmith, meaning one who "smiths words", ie. a writer.

History

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2022) |

In pre-industrialized times, smiths held high or special social standing since they supplied the metal tools needed for farming (especially the plough) and warfare.[citation needed]

Types of smiths

[edit]A metalsmith is one who works with or has the knowledge and the capacity of working with "all" metals.

Types of smiths include:[2]

- A blacksmith works with iron and steel (this is what is usually meant when referring just to "smith"). A farrier is a type of blacksmith who specializes in making and fitting horseshoes.

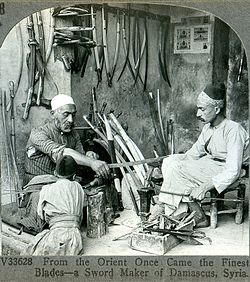

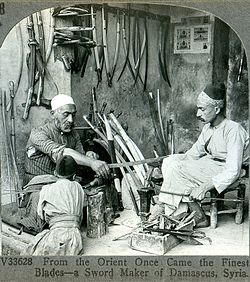

- A bladesmith forges knives, swords, and other blades.

- A brownsmith works with brass and copper.[3][citation needed]

- A coinsmith works strictly with coins and currency.

- A coppersmith works with copper.

- A goldsmith works with gold.

- A gunsmith builds and repairs firearms.

- An armourer working in an armoury maintaining and repairing small weapons traditionally had some duties of a gunsmith.

- A locksmith works with locks.

- A silversmith, or brightsmith, works with silver.[4]

- A swordsmith is a bladesmith who forges only swords.

- An arrowsmith is a blacksmith who specialises in forging arrowheads.

- A tinsmith, tinner, or tinker works with light metal (such as tinware) and can refer to someone who deals in tinware.

- A weaponsmith is a generalized bladesmith who forges weapons like axes, spears, flails, and other weapons.

- A whitesmith works with white metal (tin and pewter) and can refer to someone who polishes or finishes the metal rather than forging it.

- A tinker archaic term for an itinerant tinsmith.

Artisans and craftspeople

[edit]

The ancient traditional tool of the smith is a forge or smithy, which is a furnace designed to allow compressed air (through a bellows) to superheat the inside, allowing for efficient melting, soldering and annealing of metals. Today, this tool is still widely used by blacksmiths as it was traditionally.

The term, metalsmith, often refers to artisans and craftspersons who practice their craft in many different metals, including gold, copper and silver. Jewelers often refer to their craft as metalsmithing, and many universities offer degree programs in metalsmithing, jewelry, enameling and blacksmithing under the auspices of their fine arts programs.[5]

Machinists

[edit]Machinists are metalsmiths who produce high-precision parts and tools.[6] The most advanced of these tools, CNC machines, are computer controlled and largely automated.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Definition of METALSMITH". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ John Fuller Sr., Art of Coppersmithing, Astragal Press, 1993 (reprint of original edition, 1894) ISBN 1879335379[page needed]

- ^ "A Survey of English Bynames: Brownsmith". medievalscotland.org. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ Rupert Finegold and William Seitz, Silversmithing, Krause Publications, 1983, ISBN 0-8019-7232-9

- ^ Tim McCreight, Jewelry: Fundamentals of Metalsmithing, Hand Books Press, 1997, ISBN 1-880140-29-2

- ^ "Definition of MACHINISTS". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

External links

[edit]Metalsmith

View on GrokipediaOverview and Fundamentals

Definition and Role

A metalsmith is a skilled craftsperson who shapes metal into functional or decorative objects through processes such as heating, hammering, and finishing, producing items like tools, weapons, jewelry, and ornaments.[1][13][3] This craft encompasses working with various metals, including gold, silver, copper, and iron, often as an artisanal trade that emphasizes manual techniques to create both utilitarian goods and artistic pieces.[14][15] The term "smith" derives from the Old English word smiþ, meaning a skilled worker who strikes or works metal, originating from Proto-Germanic smiþaz and Proto-Indo-European roots related to crafting with sharp tools.[16][17] Over time, this occupational title evolved into one of the most common surnames worldwide, such as Smith in English-speaking regions or Schmidt in German, reflecting the widespread prevalence of the profession in historical communities.[18][19] In pre-industrial societies, metalsmiths held significant societal importance as essential producers of tools, implements, and weaponry that supported agriculture, construction, and defense, making them central to community survival and economic stability. Their expertise often elevated them to respected artisan status, fostering economic influence and cultural reverence, as seen in ancient civilizations where metalworking drove social development and power structures.[20][6] Metalsmithing is distinct from broader metalworking practices, which include industrial methods like machining and casting for mass production; it specifically emphasizes hand-forging and bespoke craftsmanship over automated, large-scale manufacturing.[21][22] This focus on manual processes, such as heating metal to malleability and shaping it with hammers, preserves the artisanal tradition rooted in individual skill rather than mechanical replication.[23]Core Processes

Metalsmithing fundamentally involves manipulating metal through heat and mechanical force to achieve desired shapes and properties. The core processes begin with heating the metal in a forge to render it malleable, allowing it to deform without fracturing. This heating exploits the metal's ductility—the ability to stretch under tensile stress—and malleability—the capacity to flatten under compressive stress—which increase significantly at elevated temperatures for metals like iron, copper, and silver.[24][25] Once heated, forging follows, where the metal is hammered or pressed to shape it. This process, often performed on an anvil, compresses the material to refine its grain structure and form objects from simple bars to complex tools. Common metals for forging include iron (melting point 1538°C), steel (1425–1540°C), copper (1085°C), bronze (950–1000°C), gold (1064°C), and silver (962°C), each selected for their varying degrees of malleability under heat; for instance, copper and gold are notably ductile and malleable even at moderate temperatures, while iron requires higher heat for similar workability.[26][27][28] After shaping, annealing involves controlled heating followed by slow cooling to relieve internal stresses and restore ductility, preventing brittleness in the worked metal. This step is crucial for metals like steel, which can harden during forging. Quenching, by contrast, rapidly cools heated metal—often in water or oil—to harden it, enhancing strength but requiring subsequent tempering to balance toughness.[29][30] The basic workflow transforms a raw ingot or bar through these stages: initial heating and forging to rough shape, intermittent annealing to maintain workability, optional quenching for hardening, and finishing via filing or polishing to achieve a smooth, precise surface. This sequence ensures the metal's properties align with the intended function, from durable tools in iron to ornamental pieces in silver.[31][22]Historical Development

Ancient Origins

The emergence of metalsmithing traces back to the Chalcolithic period, around 4500 BCE, when early communities in the Near East and Balkans began smelting copper from native ores to produce tools and ornaments. Archaeological evidence from sites such as Belovode in Serbia reveals the use of simple furnaces and crucibles for extracting copper, marking the transition from stone to metalworking technologies.[32] In the Near East, similar practices appeared at sites like Tel Tsaf in Israel, where a copper awl dating to the late 6th millennium BCE demonstrates the initial adoption of cold-hammered copper artifacts.[33] During the Bronze Age (c. 3300–1200 BCE), metalsmiths advanced their craft by alloying copper with tin to create bronze, a harder and more durable material ideal for tools, weapons, and ceremonial objects. This innovation originated in the Near East and spread across the Mediterranean through extensive trade networks, with tin ingots transported from distant sources like the Taurus Mountains or even as far as Britain, as evidenced by shipwrecks such as Uluburun off the coast of Turkey.[34] Key artifacts from this era include Ötzi the Iceman's copper axe from circa 3300 BCE, found in the Ötztal Alps and showcasing early arsenical copper working, as well as Sumerian bronze statues from the Early Dynastic period (c. 2900–2350 BCE) discovered in sites like Tell Asmar, which highlight intricate casting techniques.[35] Egyptian gold jewelry from the predynastic and early Bronze Age periods, such as broad-collar necklaces from tombs at Naqada, exemplifies the refinement of precious metalworking for elite adornment.[36] In Europe, Celtic iron swords from the Hallstatt culture (c. 800–450 BCE), like those from Hallstatt burials, represent the shift to iron smelting and forging for weaponry.[37] Metalsmiths in these ancient societies held elite status as specialized craftsmen, often operating under royal or religious patronage that granted them access to rare materials and workshops. In Egypt, goldsmiths and coppersmiths were integral to temple rituals and pharaonic burials, their work symbolizing divine power and ensuring the afterlife provisions of the elite.[38] Similarly, in Sumerian and other Near Eastern civilizations, metalsmiths were revered for producing votive figures and weapons tied to warfare and deity worship, elevating their social role within hierarchical communities.[39]Evolution Through Industrial Era

During the medieval period, from approximately 500 to 1500 CE, metalsmithing in Europe became increasingly organized through guild systems that regulated the practices of blacksmiths and goldsmiths, ensuring quality control, apprenticeships, and economic protection for members. These guilds, prominent in cities across England, France, and the Holy Roman Empire, controlled entry into the trade, set standards for workmanship, and often wielded significant political influence. For instance, the Worshipful Company of Blacksmiths in London, first documented in 1299, exemplified this structure by overseeing blacksmiths' activities and maintaining the craft's standards within the city.[40] Similarly, goldsmiths' guilds, such as those in medieval Paris and Florence, enforced hallmarks on precious metals to prevent fraud and monopolized the production of jewelry, religious artifacts, and tableware, elevating the profession's status amid growing urban trade.[41] The Renaissance, spanning the 14th to 17th centuries, marked a period of innovation in metalsmithing, particularly in ornamental techniques that refined medieval methods into more intricate and artistic forms. Goldsmiths like Benvenuto Cellini advanced casting, engraving, and enameling processes, creating elaborate pieces such as salt cellars and medallions that blended classical motifs with technical precision, laying groundwork for later opulent jewelry styles.[42] These developments emphasized the artisan's role as an intellectual creator, influenced by humanism and patronage from courts and churches, and extended to blacksmithing through decorative ironwork like ornate gates and balustrades that showcased filigree and repoussé.[43] The Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries profoundly transformed metalsmithing, leading to the decline of traditional hand-forging as steam-powered machinery enabled mass production and reduced reliance on individual craftsmen. Innovations like steam hammers and rolling mills mechanized iron and steel shaping, shifting blacksmiths from generalists to specialized roles in factories, while the Bessemer process, patented in 1856 by Henry Bessemer, revolutionized steelmaking by converting pig iron into steel in minutes through air injection, slashing costs from £40 to £6–7 per ton[44] and fueling infrastructure like railroads.[45] This industrialization diminished the autonomy and prestige of metalsmiths, as handcrafted items became luxury exceptions amid standardized output.[46] In response, the late 19th and early 20th centuries saw artisan revivals, notably the Arts and Crafts movement initiated by William Morris in the 1860s, which sought to counteract industrialization's dehumanizing effects by championing handcrafted metalwork. Morris's firm, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. (founded 1861), produced hammered iron and silver pieces emphasizing simplicity and medieval-inspired designs, inspiring guilds and workshops that preserved metalsmithing as a moral and aesthetic pursuit.[47] This movement influenced global craft education and elevated metalsmithing's cultural value, bridging traditional techniques with modern sensibilities.[48]Types of Metalsmiths

Traditional Specialists

Traditional metalsmith specialists emerged as distinct trades based on the properties of specific metals and the handcrafting techniques required to shape them into functional and decorative objects. These artisans relied on manual forging, hammering, and finishing methods, leveraging the ductility, malleability, and corrosion resistance of their chosen materials to produce enduring items without reliance on powered machinery. Each specialization adapted to the unique characteristics of ferrous or non-ferrous metals, focusing on products that served practical, ornamental, or ceremonial purposes across historical periods. Blacksmiths, working primarily with iron and steel, forged robust items essential for agriculture, transportation, and construction. These metals' high tensile strength and ability to withstand heat made them ideal for creating tools such as plows and axes, horseshoes to protect livestock hooves during travel, and ornate gates for enclosures and estates. Key techniques included drawing out, where a heated bar is hammered on an anvil using a cross-pein hammer to elongate and thin the metal while refining its grain structure for improved quality, and upsetting, the inverse process that shortens and thickens a heated section by hammering to build mass for structural components. These methods allowed blacksmiths to manipulate the metal's form efficiently, producing items with a characteristic hand-forged texture that enhanced both functionality and aesthetic appeal. Whitesmiths specialized in lighter, non-ferrous metals like tin and pewter, emphasizing polishing and finishing over heavy forging to achieve a bright, reflective surface. The softness and low melting point of these alloys enabled intricate work on thin sheets, resulting in decorative household goods such as candlesticks, lanterns, and utensils that combined utility with elegance. Unlike blacksmiths, whitesmiths often tinned iron bases for rust protection or crafted directly from malleable non-ferrous stock, focusing on precision assembly and surface refinement to highlight the metals' silvery sheen in everyday and ornamental settings. Goldsmiths and silversmiths handled precious metals renowned for their rarity, luster, and resistance to tarnish, crafting high-value items for personal adornment and elite table service. Goldsmiths shaped gold into jewelry like pendants and rings, while silversmiths produced tableware including platters, goblets, and cutlery, often for ceremonial or domestic use among nobility. Signature techniques encompassed repoussé, where annealed sheet metal is hammered from the reverse side against a pitch bed to raise three-dimensional relief designs without thinning the material, and chasing, which refines those forms from the front using specialized punches to compress and detail motifs like floral patterns or figures. These methods, rooted in ancient practices, allowed for intricate, lightweight constructions that showcased the metals' inherent beauty and symbolic prestige. Coppersmiths and bronzesmiths worked with copper and its alloys, exploiting the metal's excellent thermal conductivity, antimicrobial properties, and workability for both utilitarian and artistic ends. Coppersmiths hammered sheets into cookware such as kettles, pots, and casseroles, valued for even heat distribution in culinary applications, while bronzesmiths cast or forged bronze—copper alloyed with tin—for durable sculptures depicting figures, animals, or architectural elements. Techniques involved hot forging with sledgehammers on stone anvils and repoussé for surface decoration, as seen in ancient Greek statuary where lost-wax casting created hollow figures for temples and public spaces. In colonial Mexico, coppersmiths in Santa Clara del Cobre blended pre-Hispanic Purépecha methods of smelting scrap copper with European influences introduced by Franciscan friars, producing hammered vessels and ornate trays that evolved from indigenous tools and adornments into hybrid colonial artifacts.[49] These specialists' focus on the metals' reddish hue and patina ensured products that aged gracefully, serving from ancient rituals to everyday colonial life.Modern and Industrial Variants

Modern metalsmithing has evolved significantly from its traditional roots, incorporating advanced machinery and digital technologies to meet the demands of large-scale production and precision engineering. While traditional metalsmiths focused on hand-forged items, contemporary variants emphasize automated processes and specialized alloys, bridging artisanal skills with industrial efficiency. These roles emerged prominently during the Industrial Revolution and accelerated post-World War II, driven by the need for complex components in expanding sectors like manufacturing and transportation.[50] Machinists represent a key modern variant, specializing in precision shaping of metal parts using lathes, milling machines, and computer numerical control (CNC) systems for manufacturing applications. This role traces its origins to 19th-century toolmakers who developed early machine tools during the Industrial Revolution, enabling interchangeable parts production that revolutionized assembly lines. Today, machinists produce components for machinery, electronics, and vehicles, with employment reaching approximately 298,790 in the United States as of May 2024.[51][52] Welders and fabricators focus on joining metals through techniques such as arc welding and gas welding to construct large-scale structures like bridges, ships, and automotive frames. Arc welding, invented in the late 19th century, gained industrial prominence during World War II for shipbuilding and vehicle production, evolving into shielded metal arc and gas metal arc methods for enhanced durability. Fabricators often combine cutting, bending, and assembly in workshops, supporting infrastructure and heavy industry, with over 421,730 employed in the U.S. as of May 2023.[53][54] In jewelry fabrication, modern practitioners integrate computer-aided design (CAD) software and laser etching with traditional handcrafting to create intricate pieces from precious metals and gems. CAD allows for precise 3D modeling and rapid prototyping, reducing material waste and enabling complex geometries unattainable by manual methods alone, a shift that began accelerating in the late 20th century with digital tools. Laser etching provides permanent, detailed markings or patterns on metals like gold and silver, enhancing customization for high-end markets. U.S. employment in this field stood at 35,100 as of May 2024.[55][56] Automotive and aerospace metalsmiths specialize in working with high-strength alloys, such as titanium and aluminum composites, to fabricate components like engine parts, fuselages, and chassis that withstand extreme conditions. These roles developed rapidly after World War II, as postwar aviation and automobile booms demanded lightweight, durable materials; for instance, aluminum alloys became central to aircraft design starting in the 1940s. Modern practitioners use CNC machining and advanced welding to meet stringent safety standards, contributing to innovations in electric vehicles and space exploration.[57][58] The transition from artisan metalsmiths to industrial roles has been marked by significant employment growth, reflecting broader economic shifts toward mechanization and specialization. In the U.S., machinists and welders alone account for over 700,000 jobs in recent years, underscoring the scale of modern metalworking in supporting global manufacturing, though projections from 2024 to 2034 indicate mixed outlooks with a modest decline for machinists and slight growth for welders due to automation and technological advancements.[51][54][59]Tools and Techniques

Essential Equipment

The forge serves as the central heating apparatus in metalsmithing, where metal is brought to a malleable state for shaping. Common types include solid fuel forges using coal, coke, or charcoal, which require bellows or blowers to supply airflow and achieve temperatures up to 2,500°F; gas forges powered by propane for cleaner, more controlled heating; and electric induction forges suitable for precise, indoor use without open flames.[60][61] An essential striking surface is the anvil, typically weighing 100–200 pounds for stability during heavy forging, constructed from wrought iron or cast steel with a hardened face to withstand repeated impacts. Hammers, such as the cross-peen variety with a flat striking face and wedged peen for drawing out metal, complement the anvil and are available in weights from 1.5 to 3 pounds for hand forging.[62][63] Tongs are critical for safely gripping and transferring hot metal between the forge and anvil, with designs like flat-jaw or bolt tongs tailored to specific stock sizes. Chisels, including hot and cold varieties, enable cutting and texturing, while files—such as flat, half-round, and square types—smooth and refine finished surfaces after cooling.[64] A proper workspace requires robust ventilation, such as exhaust fans or open-air setups, to disperse fumes and smoke from the forge. Fire safety measures include non-flammable flooring, fire extinguishers rated for metal fires, and clear zones around heat sources to prevent ignition of nearby materials. Protective gear, including leather aprons, gloves, safety glasses, and respirators with HEPA filters, guards against burns, sparks, and airborne particulates.[65][66] For hobbyists, traditional equipment can be costly, with a basic anvil starting at $200 and a coal forge setup exceeding $500, but modern replicas like portable propane forges offer accessibility at $100–300, allowing entry-level practice without extensive infrastructure.[67][68]Key Methods and Safety

Advanced methods in metalsmithing extend beyond basic forging, which involves heating and hammering metal to shape it through compressive force, by incorporating techniques that allow for precise joining, replication of intricate forms, and decorative detailing. Soldering, for instance, uses a filler metal alloy with a lower melting point than the base metals to join components, often applied with a torch and flux to prevent oxidation, enabling the creation of seamless connections in jewelry and hollowware without altering the primary material's structure.[69] Casting, particularly the lost-wax process popular in jewelry making, differs markedly from forging by involving the creation of a wax model that is encased in investment plaster, melted out to form a mold, and then filled with molten metal, allowing for highly detailed and complex shapes that would be challenging to achieve through direct mechanical deformation. Engraving, in contrast to these formative processes, focuses on subtractive detailing by incising designs into the metal surface using specialized tools like gravers or rotary devices, adding ornamental patterns or text without significantly changing the object's overall form.[70][69] Safety protocols are essential in metalsmithing due to prevalent hazards such as thermal burns from hot tools or molten metal, inhalation of toxic fumes from soldering or casting, and eye injuries from sparks or flying debris. Personal protective equipment (PPE) mitigates these risks, including heat-resistant gloves to protect against burns, safety goggles or face shields with side shields to guard against projectiles and radiant energy, and respirators fitted for specific particulates like metal fumes when natural ventilation proves insufficient. Ventilation standards, as outlined in OSHA guidelines, require local exhaust systems for forge exhaust and welding operations to capture contaminants at the source, maintaining airflow rates of at least 100 linear feet per minute near the work area and ensuring spaces under 16 feet in ceiling height have mechanical ventilation providing no less than 2,000 cubic feet per minute per welder to prevent accumulation of hazardous substances.[71][72] Ergonomics and best practices further reduce injury risks, with proper hammer swing techniques emphasizing a loose grip to absorb shock and prevent transmission to the elbow and wrist, thereby avoiding repetitive strain injuries like carpal tunnel syndrome from prolonged forging sessions. Work surfaces should be adjusted to elbow height to maintain neutral posture, minimizing shoulder and back strain during extended hammering. For emergencies involving metal splatter or burns, immediate procedures include cooling the affected area under cool running water for at least 20 minutes to stop tissue damage progression, followed by seeking medical attention, while fire plans mandate accessible extinguishers rated for metal fires and evacuation protocols coordinated with local fire departments.[73][71] Post-2020 developments reflect a growing emphasis on sustainability and technology in metalsmithing safety, with the adoption of eco-friendly fluxes free of fluorides and other hazardous chemicals to reduce environmental impact and health risks during soldering, as promoted by professional guilds. Additionally, digital safety training apps and online platforms have emerged, offering interactive modules on hazard recognition and PPE use tailored to jewelry fabrication, enabling remote learning and simulation-based practice to enhance risk mitigation without on-site exposure.[71][74]Contemporary Practice

Education and Training

Education and training in metalsmithing encompass a range of formal and informal pathways, from hands-on apprenticeships to structured academic degrees, designed to build foundational skills and address the craft's technical demands. Traditional apprenticeships, reminiscent of guild-style systems, typically last 1 to 7 years, allowing learners to progress under experienced mentors while gaining practical expertise in forging, shaping, and finishing metals.[75][76][77] In modern contexts, unions such as the International Brotherhood of Boilermakers offer equivalent four-year programs that combine on-the-job training with classroom instruction, emphasizing welding, rigging, and fabrication for industrial applications.[78][79] Academic programs provide deeper theoretical and artistic foundations, often through university-level degrees in metalsmithing or jewelry design. For instance, the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) offers a Bachelor of Fine Arts (BFA) and Master of Fine Arts (MFA) in Jewelry + Metalsmithing, focusing on traditional techniques alongside experimental methods to develop personal visions in metalwork.[80][81] Similarly, Appalachian State University includes a BFA in Studio Art with a concentration in Jewelry & Metalsmithing, where students explore fabrication, stone setting, and digital craft processes.[82] These programs, established since the 1970s in many institutions, integrate art history and design principles to prepare graduates for professional practice.[83] Workshops and certifications offer flexible, short-term options for skill enhancement, particularly through organizations like the Artist-Blacksmith's Association of North America (ABANA), founded in 1973 to preserve and advance blacksmithing. ABANA provides conferences, classes, and a national curriculum that certifies blacksmiths across levels, from basic forging to advanced techniques.[84][85][86] Since around 2010, online platforms such as Metalsmith Academy and Victoria Lansford's Online School have expanded access with video-based courses on jewelry fabrication, enameling, and design, supported by handouts and community forums.[74][87] Skill progression in metalsmithing generally advances from basic forging and hammering—essential for shaping heated metal—to specialized areas like casting, stone setting, or welding, with practitioners often pursuing certifications to validate expertise.[88][89] The American Welding Society (AWS) Certified Welder program, a performance-based assessment, is particularly relevant for metalsmiths incorporating structural welds, testing proficiency in processes like gas metal arc welding without prerequisites.[90][91] Global variations in training reflect regional emphases, with Europe favoring rigorous vocational apprenticeships integrated into national systems, such as Germany's dual education model combining school-based learning with employer-sponsored practice.[92] In contrast, the United States relies more on community colleges for accessible, credit-based courses in metalsmithing, often as part of associate degrees or certificates in applied arts.[93] These approaches help bridge skill gaps by tailoring education to local industry needs, from artisanal jewelry in Europe to broader fabrication in the U.S.[94]Cultural and Artistic Impact

Metalsmithing has profoundly influenced artistic expressions, particularly through the studio jewelry movement that emerged in the mid-20th century and gained momentum from the 1960s onward, emphasizing handmade, innovative designs that challenged industrial production norms.[95] This movement, rooted in modernist principles, promoted the use of non-precious metals and abstract forms to democratize jewelry as wearable art, fostering a shift toward personal expression over commercial luxury.[95] Artists like Gijs Bakker exemplified this evolution with sculptural works that blurred boundaries between jewelry, furniture, and installation art, such as his "Holes Collection" series from the 1980s, which repurposed industrial materials into conceptual pieces critiquing consumerism.[96] Bakker's designs, influential in international circles since the late 1960s, integrated metalsmithing techniques with broader design philosophy, inspiring generations to view metalwork as a medium for social commentary.[96] In cultural symbolism, metalsmithing products like weapons and jewelry have long embodied folklore and identity, as seen in Viking swords, which served not only as tools of warfare but as emblems of status, wealth, and heroic legacy in Norse sagas and mythology.[97] These blades, often inscribed with runes or patterns symbolizing protection and valor, reinforced narratives of divine favor and warrior prowess in oral traditions passed down through generations.[98] In modern pop culture, custom knives crafted by contemporary metalsmiths continue this legacy, appearing in films, literature, and media as icons of craftsmanship and adventure, with makers like Chelsea Miller gaining recognition for blades that blend functionality with artistic narrative, evoking a romanticized return to handmade heritage.[99] Globally, metalsmithing traditions carry deep ritualistic and spiritual weight, as evidenced by African ironworking practices where blacksmiths are revered as mediators between the physical and supernatural realms, often performing ceremonies to honor ancestors during smelting to ensure the metal's purity and power.[100] In central African cultures, such as among the Luba people, iron forges are treated as sacred sites, linking metallurgy to kingship and societal order through burial rites that equate anvils with royal authority.[101] Similarly, Japanese swordsmithing via the tamahagane process embeds cultural reverence for discipline and impermanence, where forging "jewel steel" from iron sand in tatara furnaces is viewed as a meditative ritual symbolizing the samurai ethos of harmony between blade and spirit, preserved as intangible cultural heritage.[102] This method, dating back centuries, underscores metalsmithing's role in embodying national identity and philosophical depth in Japan.[103] Economically, metalsmithing contributes to vibrant handmade markets, with platforms like Etsy facilitating sales of forged jewelry and tools that form a significant portion of the site's $12.6 billion in gross merchandise sales for 2024, reflecting growing demand for artisanal metal crafts amid a broader handicrafts economy valued at approximately $727 billion in 2024.[104][105] Sustainability trends further amplify this impact, as artists increasingly incorporate recycled metals into sculptures and jewelry to address environmental concerns, reducing mining demands and promoting circular economies through works that transform scrap into public installations symbolizing resilience and reuse.[106] Contemporary revivals of metalsmithing thrive within the maker movement, which has spurred a resurgence of hands-on crafting since the early 2010s, encouraging hobbyists and professionals to reclaim traditional techniques in community workshops and online forums to foster innovation and local economies.[107] Events like the Quad-State Blacksmithing Conference, held annually since 1984 by the Southern Ohio Forge and Anvil group, exemplify this revival by drawing over 800 participants for demonstrations, competitions, and vendor markets, solidifying metalsmithing's place in modern cultural gatherings that blend education with artistic exchange.[108]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/metalsmith

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/smith