Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Stannane.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Stannane

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Stannane

| |||

| Other names

tin tetrahydride

tin hydride tin(IV) hydride | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| SnH4 | |||

| Molar mass | 122.71 g/mol | ||

| Appearance | colourless gas | ||

| Density | 5.4 g/L, gas | ||

| Melting point | −146 °C (−231 °F; 127 K) | ||

| Boiling point | −52 °C (−62 °F; 221 K) | ||

| Structure | |||

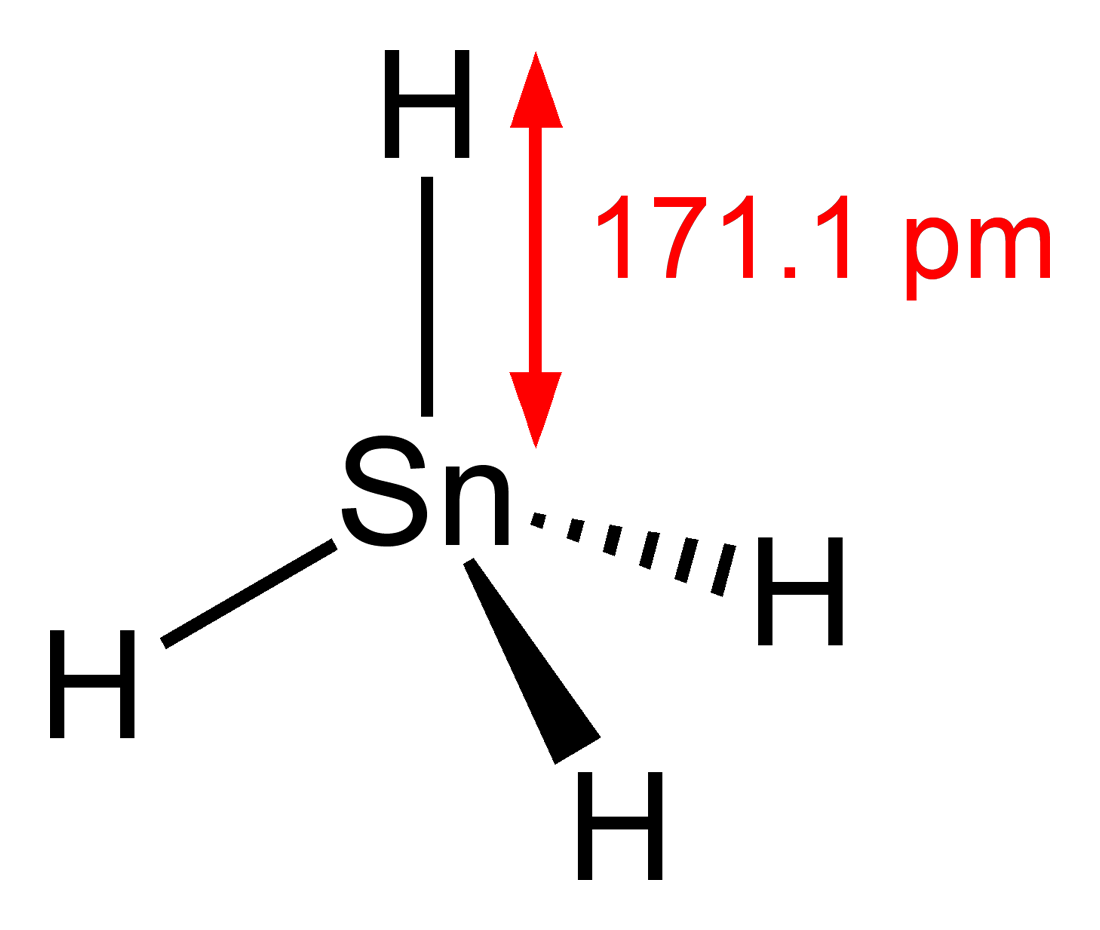

| Tetrahedral | |||

| 0 D | |||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Heat capacity (C)

|

1.262 kJ/(kg·K) | ||

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

162.8 kJ/mol | ||

Enthalpy of vaporization (ΔfHvap)

|

19.049 kJ/mol | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related organotins

|

tributylstannane (Bu3SnH) | ||

Related compounds

|

Methane Silane Germane Plumbane | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Stannane /ˈstæneɪn/ or tin hydride is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula SnH4. It is a colourless gas and the tin analogue of methane. Stannane can be prepared by the reaction of SnCl4 and Li[AlH4].[1]

- SnCl4 + Li[AlH4] → SnH4 + LiCl + AlCl3

Stannane decomposes slowly at room temperature to give metallic tin and hydrogen and ignites on contact with air.[1]

Variants of stannane can be found as a highly toxic, gaseous, inorganic metal hydrides and group 14 hydrides.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. doi:10.1016/C2009-0-30414-6. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

Stannane

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

Stannane, with the chemical formula SnH₄, is an inorganic compound consisting of one tin atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms in a tetrahedral arrangement, serving as the simplest hydride of tin and the group 14 analogue of methane.[1] It appears as a colorless, flammable gas with a molar mass of 122.71 g/mol, a melting point of -146 °C, a boiling point of -52 °C, and a density of approximately 5.4 kg/m³ in the gaseous state.[1] Due to its high reactivity and instability, stannane decomposes readily at room temperature into elemental tin and dihydrogen gas (Sn + 2H₂), making it pyrophoric and requiring careful handling under inert or cryogenic conditions.[2][3]

Stannane is typically synthesized through the reduction of tin halides, such as tin(IV) chloride (SnCl₄) with lithium aluminum hydride (LiAlH₄) in solvents like dibutyl ether or dimethoxyethane at temperatures ranging from -196 °C to -30 °C, or via tin(II) chloride (SnCl₂) with sodium borohydride (NaBH₄), which can achieve yields of up to 84%.[2] These methods produce the gas in situ for immediate use, as storage is impractical due to its thermal instability.[2]

Beyond its fundamental chemistry, stannane has emerged as a subject of significant research interest for its superconducting properties under high pressure. Synthesized experimentally at pressures of 180–210 GPa using diamond anvil cells—either by reacting SnCl₄ with LiAlH₄ or metallic tin with hydrogen sources like laser-heated ammonia borane—stannane adopts a face-centered cubic (fcc) structure (space group Fm3m).[4] This high-pressure phase exhibits superconductivity with a critical temperature (Tc) of 72 K at 180 GPa, rising to 75 K near 200 GPa, alongside a superconducting gap of 21.6 meV and non-Fermi-liquid behavior.[4] Such findings position stannane as a candidate for studying hydrogen-rich superconductors, though practical applications remain exploratory.

In industrial contexts, stannane arises as an unstable by-product during hydrogen plasma cleaning of tin deposits in extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography systems for semiconductor manufacturing, where its decomposition can lead to redeposition on optical components, necessitating advanced vacuum management strategies.[2] Overall, while primarily a laboratory compound, stannane's unique reactivity and pressure-induced properties highlight its role in advancing inorganic chemistry and materials science.