Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Surgical suture

View on Wikipedia| Surgical suture | |

|---|---|

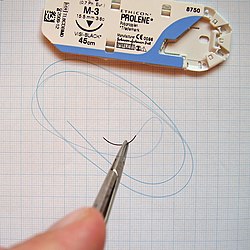

Surgical suture and 6-0 gauge polypropylene thread held with a needle holder. Packaging shown above. |

A surgical suture, also known as a stitch or stitches, is a medical device used to hold body tissues together and approximate wound edges after an injury or surgery. Application generally involves using a needle with an attached length of thread. There are numerous types of suture which differ by needle shape and size as well as thread material and characteristics. Selection of surgical suture should be determined by the characteristics and location of the wound or the specific body tissues being approximated.[1]

In selecting the needle, thread, and suturing technique to use for a specific patient, a medical care provider must consider the tensile strength of the specific suture thread needed to efficiently hold the tissues together depending on the mechanical and shear forces acting on the wound as well as the thickness of the tissue being approximated. One must also consider the elasticity of the thread and ability to adapt to different tissues, as well as the memory of the thread material which lends to ease of use for the operator. Different suture characteristics lend way to differing degrees of tissue reaction and the operator must select a suture that minimizes the tissue reaction while still keeping with appropriate tensile strength.[2]

Needles

[edit]

Historically, surgeons used reusable needles with holes (called "eyes"), which must be threaded before use just as is done with a needle and thread prior to sewing fabric. The advantage of this is that any combination of thread and needle may be chosen to suit the job at hand. Swaged (or "atraumatic") needles with sutures consist of a pre-packed eyeless needle already attached (by swaging) to a specific length of suture thread. This saves time, and eliminates the most difficult threading of very fine needles and sutures.

Two additional benefits are reduced drag and less potential damage to friable tissue during suturing. In a swaged suture the thread is of narrower diameter than the needle, whereas it protrudes on both sides in an eyed needle. Being narrower, the thread in a swaged suture has less drag when passing through tissue than the needle, and, not protruding, is less likely to traumatize friable tissue, earning the combination the designation "atraumatic".[citation needed]

There are several shapes of surgical needles. These include:[citation needed]

- Straight

- 1/4 circle

- 3/8 circle

- 1/2 circle. Subtypes of this needle shape include, from larger to smaller size, CT, CT-1, CT-2 and CT-3.[3]

- 5/8 circle

- compound curve

- half curved (also known as ski)

- half curved at both ends of a straight segment (also known as canoe)

The ski and canoe needle design allows curved needles to be straight enough to be used in laparoscopic surgery, where instruments are inserted into the abdominal cavity through narrow cannulas.

Needles may also be classified by their point geometry; examples include:

- taper (needle body is round and tapers smoothly to a point)

- cutting (needle body is triangular and has a sharpened cutting edge on the inside curve)

- reverse cutting (cutting edge on the outside)

- trocar point or tapercut (needle body is round and tapered, but ends in a small triangular cutting point)

- blunt points for sewing friable tissues

- side cutting or spatula points (flat on top and bottom with a cutting edge along the front to one side) for eye surgery

Finally, atraumatic needles may be permanently swaged to the suture or may be designed to come off the suture with a sharp straight tug. These "pop-offs" are commonly used for interrupted sutures, where each suture is only passed once and then tied.

Sutures can withstand different amounts of force based on their size; this is quantified by the U.S.P. Needles Pull Specifications.[citation needed]

Thread

[edit]Materials

[edit]

Suture material is often broken down into absorbable thread versus non-absorbable thread, which is further delineated into synthetic fibers versus natural fibers. Another important distinction among suture material is whether it is monofilament or polyfilament (braided) [2]

Monofilament versus polyfilament

[edit]Monofilament fibers have less tensile strength but create less tissue trauma and are more appropriate with delicate tissues where tissue trauma can be more significant such as small blood vessels. Polyfilament (braided) sutures are composed of multiple fibers and are generally greater in diameter with greater tensile strength, however, they tend to have greater tissue reaction and theoretically have more propensity to harbor bacteria.[1]

Other properties to consider

[edit]- Tensile strength: the ability of the suture to hold tissues in place without breaking.

- Elasticity: the ability of the suture material to adapt to changing tissues such as in cases of edema.

- Tissue reactivity: inflammatory response of the surrounding tissue that can cause materials to break down quicker and lose tensile strength. Non absorbable synthetic suture have the lowest of tissue reactivity, while the absorbable natural fibers have the highest rates of tissue reactivity.[4]

- Knot security: the ability of the suture to maintain a knot that holds the thread in place.[2]

Absorbable

[edit]Absorbable sutures are either degraded via proteolysis or hydrolysis and should not be utilized on body tissue that would require greater than two months of tensile strength. It is generally used internally during surgery or to avoid further procedures for individuals with low likelihood of returning for suture removal.[2] To-date, the available data indicates that the objective short-term wound outcomes are equivalent for absorbable and non-absorbable sutures, and there is equipoise amongst surgeons.[5]

Natural absorbable

[edit]Natural absorbable material includes plain catgut, chromic catgut and fast catgut which are all produced from the collagen extracted from bovine intestines. They are all polyfilaments which have different degradations times ranging from 3–28 days.[2] This material is often used for body tissue with low mechanical or shearing force and rapid healing time.

Plain gut (polyfilament)

[edit]- Description: Maintains original strength for 7–10 days and full degradation occurs in 10 weeks.

- Advantages/disadvantages: Excellent elasticity allowing for adaptation to tissue swelling. Passes through the skin with very little tissue trauma occurrence. Poor handling and high tissue reactivity causing quick loss of tensile strength.

- Common use: best used in rapidly healing tissues with good blood supply i.e. mucosal tissues.[6]

Chromic gut (polyfilament)

[edit]- Description: Maintains original strength for 21–28 days and full degradation occurs in 16–18 weeks.

- Advantages/disadvantages: Excellent elasticity allowing for adaptation to tissue swelling. Passes through the skin with very little tissue trauma occurrence. Improved handling and decreased tissue reactivity due to chromic salt coating.

- Common use: skin closure (face), mucosa, genitalia.[6]

Fast gut (polyfilament)

[edit]- Description: Treated with heat to further break down protein and allow for more rapid absorption in bodily tissues. Tensile strength less than a week (3–5 days).[2]

- Advantages/disadvantages: Excellent elasticity allowing for adaptation to tissue swelling. Passes through the skin with very little tissue trauma occurrence.

- Common use: Advised for skin closure only generally on the mucosa or face.[6]

Synthetic absorbable

[edit]Synthetic absorbable material includes polyglactic acid, polyglycolic acid, poliglecaprone, polydioxanone, and polytrimethylene carbonate. Among these are monofilaments, polyfilaments and braided sutures. In general synthetic materials will keep tensile strength for longer due to less local tissue inflammation.[2]

Poliglecaprone (monofilament, Monocryl, Monocryl Plus, Suruglyde)

[edit]- Description: copolymer of synthetic materials. Loses tensile strength quickly; sixty percent lost in the first week. All strength lost within 3 weeks.[7]

- Advantages/disadvantages: high tensile strength, excellent elasticity, excellent cosmetic outcomes, decreased hypertrophic scarring, minimal tissue reaction, good knot security originally; however, the material makes the security unreliable over time, thus it is important to keep ears of material long.

- Common use: Advised for subcutaneous and superficial tissue closure.

Polyglycolic acid (polyfilament, Dexon)

[edit]- Description: synthetic polymer that loses all tensile strength in by 25 days. Either dyed green for visibility or undyed.

- Advantages/disadvantages: minimal tissue reaction, good tensile strength, good handling, but poor knot security.

- Common use: subcutaneous tissue.

Polyglactin 910 (polyfilament, Vicryl)

[edit]- Description: loss of all tensile strength in 28 days.

- Advantages/disadvantages: minimal tissue reaction, good tensile strength, good knot security,

- Common use: subcutaneous tissue, skin closure (avoid dyed Vicryl on face).

Polyglactin 910 Irradiated (polyfilament, Vicryl Rapid)

[edit]- Description: sourced as vicryl is with irradiation to break down material for quicker absorption. Loss of all tensile strength in 5–7 days.

- Advantages/disadvantages: minimal tissue reaction, good tensile strength, fair good handling and good knot security.

- Common use: scalp and facial laceration closure.

Polyglyconate (monofilament, Maxon)

[edit]- Description: co polymer product of synthetic materials. Loses 75% of the tensile strength after 40 days.

- Advantages/disadvantages: minimal tissue reaction, excellent tensile strength, good handling.

- Common use: subcutaneous use often an alternative to PDS due to better handling and slightly superior tensile strength.

Polydioxanone closures (PDS, monofilament)

[edit]- Description: loss of tensile strength in 36–53 days.

- Advantages/disadvantages: minimal tissue reaction, good tensile strength, but poor handling.

- Common use: subcutaneous with need of high tensile strength (abdominal incision closure).[6]

Non-absorbable

[edit]These sutures hold greater tensile strength for longer periods of time and are not subject to degradation. They are appropriate for tissues with a high degree of mechanical or shear force (tendons, certain skin location). They also supply the operator with greater ease of use due to less thread memory.[6]

Natural

[edit]Silk (polyfilament, Permahand, Ethicon; Sofsilk, Covidien)

- Description: surgical silk is a protein derived from silkworms that is coated to minimize friction and water absorption.

- Advantages/disadvantages: This material has good tensile strength, is easy to handle and has excellent knot security. However, it is rarely used internally due to its significant tissue reaction which causes loss of tensile strength over months.

- Common use: Due to advancements in sutures, there is no longer indication for use of surgical silk. However, it is still commonly used in dentistry for mucosal surfaces[8] or to secure surgical tubes on the bodies surface.

Synthetic

[edit]Synthetic materials include nylon, polypropylene and surgical steel all of which are monofilaments with great tensile strength.[2]

Nylon (monofilaments, Dermalon, Ethilon)

- Description: polyamide

- Advantages/disadvantages: Excellent tensile strength. However, poor handling and poor knot security due to high material memory.

- Common use: Excellent for superficial skin closure due to minimal tissue reactivity.[6] It is the most commonly used skin suture due to its excellent adaptability to potentially expanding tissues (edema).[9]

Nylon (polyfilaments, Nurolon, Surgilon, Supramid)

- Description: polyamide

- Advantages/disadvantages: Excellent tensile strength, increased usability, and increased knot security as compared to its monofilamentous counterpart. However, its polyfilamentous nature is said[weasel words] to increase risk of infection.

- Common use: soft tissue, vessel ligations and superficial skin (specifically facial lacerations).[6]

Braided polyester (polyfilament, Ethibond, Dagrofil, Synthofil, PremiCron, Synthofil)

- Description: made from polyethylene terephthalate, there are various brands and configurations of this type of suture. Many are braided, coated in silicone and dyed for visibility.

- Advantages/disadvantages: Good handling, good knot security and high tensile strength due to low tissue reactivity. However, this suture can create more tissue trauma when passing through the skin and is more expensive than its counterparts

- Common use: Rare, pediatric valvular surgery,[10] alternative to surgical steel for orthopedic surgery due to superior handling.[11]

Polybutester (monofilament, Novafil)

- Description: A copolymer of polyester.

- Advantages/disadvantages: low tissue reactivity, good handling, high tensile strength that is greater than most other monofilaments, good elasticity during increasing edema.

- Common use: rare, tendon repairs, plastics (pull out subcuticular stitch)[6]

Surgical steel

- Description: synthetic mixture of multiple alloys.

- Advantages/disadvantages: Tensile strength is exceptional with very little tissue reactivity, thus maintaining minimal degradation over time. This suture material has very poor handling.

- Common use: orthopedics, sternum closure.[2]

Sizes

[edit]Suture sizes are defined by the United States Pharmacopeia (U.S.P.). Sutures were originally manufactured ranging in size from #1 to #6, with #1 being the smallest. A #4 suture would be roughly the diameter of a tennis racquet string. The manufacturing techniques, derived at the beginning from the production of musical strings, did not allow thinner diameters. As the procedures improved, #0 was added to the suture diameters, and later, thinner and thinner threads were manufactured, which were identified as #00 (#2-0 or #2/0) to #000000 (#6-0 or #6/0).[citation needed]

Modern sutures range from #5 (heavy braided suture for orthopedics) to #11-0 (fine monofilament suture for ophthalmics). Atraumatic needles are manufactured in all shapes for most sizes. The actual diameter of thread for a given U.S.P. size differs depending on the suture material class.

| USP designation |

Collagen diameter (mm) |

Synthetic absorbable diameter (mm) |

Non-absorbable diameter (mm) |

American wire gauge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11-0 | 0.01 | |||

| 10-0 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| 9-0 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| 8-0 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| 7-0 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| 6-0 | 0.1 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 38–40 |

| 5-0 | 0.15 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 35–38 |

| 4-0 | 0.2 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 32–34 |

| 3-0 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 29–32 |

| 2-0 | 0.35 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 28 |

| 0 | 0.4 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 26–27 |

| 1 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 25–26 |

| 2 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 23–24 |

| 3 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 22 |

| 4 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 21–22 |

| 5 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 20–21 | |

| 6 | 0.8 | 19–20 | ||

| 7 | 18 |

Techniques

[edit]

Many different techniques exist. The most common is the simple interrupted stitch;[12] it is indeed the simplest to perform and is called "interrupted" because the suture thread is cut between each individual stitch. The vertical and horizontal mattress stitch are also interrupted but are more complex and specialized for everting the skin and distributing tension. The running or continuous stitch is quicker but risks failing if the suture is cut in just one place; the continuous locking stitch is in some ways a more secure version. The chest drain stitch and corner stitch are variations of the horizontal mattress.[citation needed]

Other stitches or suturing techniques include:

- Purse-string suture, a continuous, circular inverting suture which is made to secure apposition of the edges of a surgical or traumatic wound.[13][14]

- Figure-of-eight stitch

- Subcuticular stitch. A continuous suture where the needle enters and exits the epidermis along the plane of the skin. This stitch is for approximating superficial skin edges and provides the best cosmetic result. Superficial gapping wounds may be reduced effectively by using continuous subcuticular sutures.[15] It is unclear whether subcuticular sutures can reduce the rate of surgical site infections.when compared with other suturing methods.[16]

Placement

[edit]Sutures are placed by mounting a needle with attached suture into a needle holder. The needle point is pressed into the flesh, advanced along the trajectory of the needle's curve until it emerges, and pulled through. The trailing thread is then tied into a knot, usually a square knot or surgeon's knot. Ideally, sutures bring together the wound edges, without causing indenting or blanching of the skin,[17] since the blood supply may be impeded and thus increase infection and scarring.[18][19] Ideally, sutured skin rolls slightly outward from the wound (eversion), and the depth and width of the sutured flesh is roughly equal.[18] Placement varies based on the location.

Stitching interval and spacing

[edit]Skin and other soft tissue can lengthen significantly under strain. To accommodate this lengthening, continuous stitches must have an adequate amount of slack. Jenkin's rule was the first research result in this area, showing that the then-typical use of a suture-length to wound-length ratio of 2:1 increased the risk of a burst wound, and suggesting a SL:WL ratio of 4:1 or more in abdominal wounds.[19][20] A later study suggested 6:1 as the optimal ratio in abdominal closure.[21]

Layers

[edit]In contrast to single layer suturing, two layer suturing generally involves suturing at a deeper level of a tissue followed by another layer of suturing at a more superficial level. For example, Cesarean section can be performed with single or double layer suturing of the uterine incision.[22]

Removal

[edit]Whereas some sutures are intended to be permanent, and others in specialized cases may be kept in place for an extended period of many weeks, as a rule sutures are a short-term device to allow healing of a trauma or wound.

Different parts of the body heal at different speeds. Common time to remove stitches will vary: facial wounds 3–5 days; scalp wound 7–10 days; limbs 10–14 days; joints 14 days; trunk of the body 7–10 days.[23][better source needed]

Removal of sutures is traditionally achieved by using forceps to hold the suture thread steady and pointed scalpel blades or scissors to cut. For practical reasons the two instruments (forceps and scissors) are available in a sterile kit. In certain countries (e.g. US), these kits are available in sterile disposable trays because of the high cost of cleaning and re-sterilization.

Expansions

[edit]A pledgeted suture is one that is supported by a pledget, that is, a small flat non-absorbent pad normally composed of polytetrafluoroethylene, used as buttresses under sutures when there is a possibility of sutures tearing through tissue.[24]

Tissue adhesives

[edit]Topical cyanoacrylate adhesives (closely related to super glue), have been used in combination with, or as an alternative to, sutures in wound closure. The adhesive remains liquid until exposed to water or water-containing substances/tissue, after which it cures (polymerizes) and forms a bond to the underlying surface. The tissue adhesive has been shown to act as a barrier to microbial penetration as long as the adhesive film remains intact. Limitations of tissue adhesives include contraindications to use near the eyes and a mild learning curve on correct usage. They are also unsuitable for oozing or potentially contaminated wounds.[citation needed]

In surgical incisions it does not work as well as sutures as the wounds often break open.[25]

Cyanoacrylate is the generic name for cyanoacrylate based fast-acting glues such as methyl-2-cyanoacrylate, ethyl-2-cyanoacrylate (commonly sold under trade names like Superglue and Krazy Glue) and n-butyl-cyanoacrylate. Skin glues like Indermil and Histoacryl were the first medical grade tissue adhesives to be used, and these are composed of n-butyl cyanoacrylate. These worked well but had the disadvantage of having to be stored in the refrigerator, were exothermic so they stung the patient, and the bond was brittle. Nowadays, the longer chain polymer, 2-octyl cyanoacrylate, is the preferred medical grade glue. It is available under various trade names, such as LiquiBand, SurgiSeal, FloraSeal, and Dermabond. These have the advantages of being more flexible, making a stronger bond, and being easier to use. The longer side chain types, for example octyl and butyl forms, also reduce tissue reaction.

History

[edit]

Through many millennia, various suture materials were used or proposed. Needles were made of bone or metals such as silver, copper, and aluminium bronze wire. Sutures were made of plant materials (flax, hemp and cotton) or animal material (hair, tendons, arteries, muscle strips and nerves, silk, and catgut).[citation needed]

The earliest reports of surgical suture date to 3000 BC in ancient Egypt, and the oldest known suture is in a mummy from 1100 BC. A detailed description of a wound suture and the suture materials used in it is by the Indian sage and physician Sushruta, written in 500 BC.[26] The Greek father of medicine, Hippocrates, described suture techniques, as did the later Roman Aulus Cornelius Celsus. The 2nd-century Roman physician Galen described sutures made of surgical gut or catgut.[27] In the 10th century, the catgut suture along with the surgery needle were used in operations by Abulcasis.[28][29] The gut suture was similar to that of strings for violins, guitars, and tennis racquets and it involved harvesting sheep or cow intestines. Catgut sometimes led to infection due to a lack of disinfection and sterilization of the material.[30]

Joseph Lister endorsed the routine sterilization of all suture threads. He first attempted sterilization with the 1860s "carbolic catgut", and chromic catgut followed two decades later. Sterile catgut was finally achieved in 1906 with iodine treatment.

The next great leap came in the twentieth century. The chemical industry drove production of the first synthetic thread in the early 1930s, which exploded into production of numerous absorbable and non-absorbable synthetics. The first synthetic absorbable was based on polyvinyl alcohol in 1931. Polyesters were developed in the 1950s, and later the process of radiation sterilization was established for catgut and polyester. Polyglycolic acid was discovered in the 1960s and implemented in the 1970s. Today, most sutures are made of synthetic polymer fibers. Silk and, rarely, gut sutures are the only materials still in use from ancient times. In fact, gut sutures have been banned in Europe and Japan owing to concerns regarding bovine spongiform encephalopathy. Silk suture is still used today, mainly to secure surgical drains.[31]

See also

[edit]- Alexis Carrel – French surgeon and biologist (1873–1944)

- Barbed suture – Type of knotless surgical suture

- Butterfly closure – Small self-adhesive medical dressing

- Cheesewiring – Cutting of tissue by a taut element

- Chitin – Long-chain polymer of a N-acetylglucosamine

- Cyanoacrylate – Type of fast-acting adhesive

- Knot – Method of fastening or securing linear materials

- Ligature – Piece of thread (suture) tied around an anatomical structure

- Outline of medicine – Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of illness

- Sewing – Craft of fastening textiles with a needle and thread

- Surgical staple – Staples used in surgery in place of sutures

- Wound closure strip – Porous surgical tape used for closing small wounds

References

[edit]- ^ a b Byrne, Miriam; Aly, Al (2019-03-14). "The Surgical Suture". Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 39 (Supp. 2): S67 – S72. doi:10.1093/asj/sjz036. ISSN 1090-820X. PMID 30869751.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Jeffrey M. Sutton; et al., eds. (2018). The Mont Reid surgical handbook. Philadelphia, PA. pp. 81–90. ISBN 978-0-323-53174-0. OCLC 1006511397.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Surgical Needle Guide Archived 2014-11-06 at the Wayback Machine from Novartis. Copyright 2005.

- ^ Shan R. Baker, ed. (2007). Local flaps in facial reconstruction. Mosby Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-03684-9. OCLC 489075341.

- ^ Lee, Alice; Stanley, Guy H. M.; Wade, Ryckie G.; Berwick, Daniele; Vinicombe, Victoria; Salence, Brogan K.; Musbahi, Esra; De Poli, Anderson R. C. S.; Savu, Mihaela; Batchelor, Jonathan M.; Abbott, Rachel A.; Gardiner, Matthew D.; Wernham, Aaron; Veitch, David; Ghaffar, S. A. (2023-02-08). "International, prospective cohort study comparing non-absorbable versus absorbable sutures for skin surgery: CANVAS service evaluation" (PDF). British Journal of Surgery. 110 (4): 462–470. doi:10.1093/bjs/znad008. ISSN 0007-1323. PMID 36753053.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Trott, Alexander (2012). Wounds and lacerations: emergency care and closure. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. ISBN 978-0-323-09132-9. OCLC 793588304.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Langley-Hobbs, S. J.; Demetriou, Jackie; Ladlow, Jane, eds. (2013). Feline soft tissue and general surgery. Edinburgh. ISBN 978-0-7020-5420-4. OCLC 865542682.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Singer, Adam J.; Hollander, Judd E.; Blumm, Robert M., eds. (2010). Skin and soft tissue injuries and infections: a practical evidence based guide. Shelton, Connecticut: People's Medical. ISBN 978-1-60795-201-5. OCLC 801407265.

- ^ Ducheyne, Paul; et al., eds. (2011). Comprehensive biomaterials. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-055294-1. OCLC 771916865.

- ^ Anderson, Robert H.; et al., eds. (2010). Paediatric cardiology. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-3735-1. OCLC 460904281.

- ^ Wright, James G.; et al., eds. (2009). Evidence-based orthopaedics: the best answers to clinical questions. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4377-1113-4. OCLC 460904348.

- ^ Lammers, Richard L; Trott, Alexander T (2004). "Chapter 36: Methods of Wound Closure". In Roberts, James R; Hedges, Jerris R (eds.). Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. p. 671. ISBN 978-0-7216-9760-4.

- ^ Dorland's Medical Dictionary for Health Consumers. Copyright 2007

- ^ Miller-Keane Encyclopedia & Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, and Allied Health, Seventh Edition.

- ^ Gurusamy, Kurinchi Selvan; Toon, Clare D; Allen, Victoria B; Davidson, Brian R (2014-02-14). Cochrane Wounds Group (ed.). "Continuous versus interrupted skin sutures for non-obstetric surgery". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (2) CD010365. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010365.pub2. PMC 10692401. PMID 24526375.

- ^ Goto, Saori; Sakamoto, Takashi; Ganeko, Riki; Hida, Koya; Furukawa, Toshi A; Sakai, Yoshiharu (2020-04-09). Cochrane Wounds Group (ed.). "Subcuticular sutures for skin closure in non-obstetric surgery". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (4) CD012124. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012124.pub2. PMC 7144739. PMID 32271475.

- ^ Osterberg, B; Blomstedt, B (1979). "Effect of suture materials on bacterial survival in infected wounds: An experimental study". Acta Chir Scand. 145 (7): 431–4. PMID 539325.

- ^ a b Macht, SD; Krizek, TJ (1978). "Sutures and suturing - Current concepts". Journal of Oral Surgery. 36 (9): 710–2. PMID 355612.

- ^ a b Kirk, RM (1978). Basic Surgical Techniques. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

- ^ Grossman, JA (1982). "The repair of surface trauma". Emergency Medicine. 14: 220.

- ^ Varshney, S; Manek, P; Johnson, CD (September 1999). "Six-fold suture:wound length ratio for abdominal closure". Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 81 (5): 333–6. PMC 2503300. PMID 10645176.

- ^ Stark, M.; Chavkin, Y.; Kupfersztain, C.; Guedj, P.; Finkel, A. R. (1995). "Evaluation of combinations of procedures in cesarean section". International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 48 (3): 273–6. doi:10.1016/0020-7292(94)02306-J. PMID 7781869. S2CID 72559269.

- ^ "www.scribd.com". Archived from the original on 24 August 2013.

- ^ "Polytetrafluoroethylene Pledget".

- ^ Dumville, JC; Coulthard, P; Worthington, HV; Riley, P; Patel, N; Darcey, J; Esposito, M; van der Elst, M; van Waes, OJ (28 November 2014). "Tissue adhesives for closure of surgical incisions". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (11) CD004287. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004287.pub4. PMC 10074547. PMID 25431843.

- ^ Mysore, Venkataram (2012-12-15). Acs(I) Textbook on Cutaneous and Aesthetic Surgery. Jaypee Brothers. pp. 125–126. ISBN 978-93-5090-591-3. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ^ Nutton, Vivian (2005-07-30). Ancient Medicine. Taylor & Francis US. ISBN 978-0-415-36848-3. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

- ^ Rooney, Anne (2009). The Story of Medicine. Arcturus. ISBN 978-1-84858-039-8.

- ^ Rakel, David; Rakel, Robert E. (2011). Textbook of Family Medicine E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-1-4377-3567-3.

- ^ Chen, Hua; Wu, Kejian; Tang, Peifu; Zhang, Yixin; Fu, Zhongguo, eds. (2021). Tutorials in Suturing Techniques for Orthopedics. Springer Nature. p. 7. ISBN 978-981-336-330-4.

- ^ Rai, Anshul; Panneerselvam, Elavenil; Bonanthaya, Krishnamurthy; Manuel, Suvy; Kumar, Vinay V., eds. (2021). Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery for the Clinician. Springer Singapore. p. 231. ISBN 978-981-15-1346-6.

External links

[edit]Surgical suture

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition and purpose

Surgical sutures are sterile surgical threads designed to approximate the edges of divided tissues, facilitating wound closure, promoting healing, and reducing the risk of infection. They serve as a critical tool in surgical procedures by enabling precise alignment of tissue layers, which supports the natural healing process through primary intention. According to regulatory standards, sutures are classified as Class II medical devices intended for soft tissue approximation and/or ligation.[10][11] The primary purposes of surgical sutures include achieving hemostasis to control bleeding, ensuring tissue approximation for optimal edge alignment, obliterating dead space to prevent fluid accumulation and seroma formation, and promoting eversion of wound edges to minimize scarring and enhance cosmetic outcomes. These functions collectively minimize complications such as dehiscence and infection while supporting tissue regeneration. For instance, proper eversion maximizes epidermal contact and reduces tension on the wound, aiding in scarless healing.[11][12] Surgical sutures find common applications across diverse medical fields, including general surgery for abdominal wound closure, orthopedics for tendon repair and cerclage, cardiovascular procedures for vascular anastomosis, plastic surgery for precise cosmetic closures, and obstetrics for episiotomy repair. Their versatility stems from adaptability to various tissue types and procedural demands.[10][11] Basic principles guiding suture use emphasize tension distribution to avoid excessive stress on healing tissues, biocompatibility to minimize inflammatory responses, and appropriate tensile strength tailored to the specific tissue type—such as higher strength for musculoskeletal tissues versus finer gauges for delicate dermal layers. Selection considers factors like wound location and expected mechanical loads to ensure secure knotting and long-term integrity.[11][13][14]Historical context overview

The use of surgical sutures dates back to ancient civilizations, with the earliest documented evidence appearing in ancient Egypt around 3000 BCE, where physicians employed linen threads and animal sinew to close wounds on both the living and in mummification practices.[15] In ancient India, around 600 BCE, the surgeon Sushruta, often regarded as the father of surgery, described innovative wound closure methods in the Sushruta Samhita, including the use of large black ants whose heads were applied to pinch skin edges together as natural staples, as well as bark fibers from trees like the asmantaka for threading sutures.[16] These early techniques relied on readily available natural materials and laid foundational principles for wound approximation, though infection risks remained high due to the absence of sterilization. During the medieval period, advancements in the Islamic world elevated suture practices, with 10th-century Arab surgeon Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (Albucasis) pioneering the use of catgut—derived from animal intestines—for internal stitches and silk for external wounds, as detailed in his comprehensive 30-volume medical encyclopedia Al-Tasrif.[17] These materials offered improved tensile strength and reduced tissue reaction compared to earlier options. By the 16th century in Europe, French military surgeon Ambroise Paré further popularized catgut sutures, integrating them into battlefield medicine and emphasizing ligatures over cauterization to control bleeding, which marked a shift toward more humane and effective surgical interventions.[18] The transition to modern suturing accelerated in the late 19th century with Joseph Lister's introduction of antiseptic techniques in 1867, which drastically reduced postoperative infections and enabled safer use of natural materials like catgut and silk.[19] In the early 20th century, mechanical alternatives emerged, such as the first surgical stapler invented by Hungarian surgeon Hümér Hültl in 1908, which used metal staples to approximate tissues more rapidly, serving as a precursor to contemporary devices.[20] Key regulatory milestones followed, including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) enforcement of sterility standards for surgical sutures under the 1938 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, with intensified oversight in the 1940s amid wartime medical demands to ensure device safety and efficacy.[21] The mid-20th century saw a pivotal shift toward synthetic materials, with the 1960s introduction of polymers like polyglycolic acid revolutionizing suture design by providing predictable absorption rates, greater uniformity, and reduced inflammatory responses compared to animal-derived options.[2] This era's innovations, driven by chemical advancements, set the foundation for today's diverse suture portfolio while maintaining the core objective of secure wound closure.Components

Needles

Surgical needles are precision instruments designed to penetrate biological tissues with controlled trauma, facilitating the accurate placement of suture material during surgical procedures. The basic anatomy of a surgical needle comprises three primary components: the point, the body, and the attachment end. The point, located at the distal tip, determines the manner of tissue entry and is engineered to balance penetration ease with minimal damage; common variants include tapered points for smooth displacement of soft tissues, cutting points with sharpened edges for tougher structures like skin, and blunt points to avoid tearing friable tissues. The body forms the shaft, providing structural integrity and defining the needle's trajectory, while the attachment end connects to the suture, either via an open eye or a seamless swage.[22][23] Needles are classified by body shape and point configuration to suit diverse surgical needs. Straight-bodied needles allow direct manual control and are typically employed for superficial closures, such as skin suturing, where visibility and access are straightforward. Curved-bodied needles, the predominant type, arc in fractions of a circle—ranging from 1/4 to 3/8 circle for confined spaces like cardiovascular or urologic procedures, to 1/2 or 5/8 circle for broader access in general surgery—to enable efficient tissue passage without excessive manipulation. Specialized forms include trocar-point needles, featuring a tapered, three-faceted tip for minimally invasive techniques, reducing the risk of unintended organ perforation. Cutting points, often reverse-cutting with the cutting edge on the convex side, excel in dense tissues by slicing cleanly and minimizing pull-through, whereas non-cutting tapered or blunt variants preserve tissue integrity in vascular or gastrointestinal applications.[24][25][5] Construction materials prioritize strength, flexibility, and biocompatibility to withstand surgical stresses without deformation or breakage. Most surgical needles are fabricated from 300-series stainless steel alloys, valued for their corrosion resistance, sharpness retention, and ability to maintain form under torsion. For enhanced durability in demanding applications, such as cardiovascular surgery, tungsten-rhenium alloys may be incorporated to increase tensile strength. Surface coatings, including silicone or polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), are applied to diminish frictional drag on tissues, thereby reducing insertion force and postoperative inflammation.[26][23] Attachment methods influence handling efficiency and sterility. Eyed needles feature a closed or open loop at the proximal end, necessitating intraoperative threading of the suture, which suits reusable scenarios but risks contamination and time loss. In contrast, swaged (or eyeless) needles integrate the suture directly into the shank via a crimped or molded attachment, ensuring a smooth, atraumatic profile and pre-sterilization; this design prevents suture slippage, enhances knot security, and is standard for disposable, single-use sutures in contemporary practice.[10][22] Needle selection hinges on tissue characteristics, procedural demands, and anatomical constraints to optimize outcomes and minimize complications. For delicate, low-density tissues like those in ophthalmic or microsurgery, fine-gauge tapered or blunt needles (e.g., 10-0 size) are preferred to avoid excessive trauma. In contrast, denser tissues such as abdominal fascia or dermis require robust cutting needles (e.g., 3/8 circle reverse-cutting) to ensure clean penetration with reduced surgeon fatigue. Access limitations, as in laparoscopic procedures, favor half-circle or ski-shaped designs for instrument compatibility, while overall needle length and diameter are scaled to match wound depth and suture caliber, always prioritizing the smallest viable size to limit tissue disruption.[23][27]Threads

Surgical suture threads form the essential ligature component that approximates and holds tissue edges together during wound closure and healing. These threads are engineered to balance mechanical performance with biocompatibility, enabling precise surgical manipulation. The primary configurations of suture threads are monofilament and polyfilament, each offering distinct advantages in clinical application. Monofilament threads consist of a single, uniform strand of material, which allows for smooth passage through tissues, minimizes tissue drag, and reduces the risk of bacterial harboring due to the absence of voids.[23] In contrast, polyfilament threads are composed of multiple finer strands that are either braided or twisted together, resulting in enhanced pliability, superior knot security, and higher overall tensile strength compared to monofilaments of equivalent diameter, though they may require coatings to mitigate potential infection risks from interstices.[5] The core functions of suture threads revolve around providing sufficient tensile strength to withstand physiological stresses during the healing process, ensuring reliable knot security to prevent unraveling under tension, and offering optimal handling properties that facilitate ease of tying and placement without excessive memory or stiffness.[28] Tensile strength refers to the maximum load the thread can endure before breaking, which is critical for maintaining wound integrity, while knot security determines the knot's resistance to slippage, influenced by the thread's coefficient of friction and construction. Handling properties, including flexibility and knot run-down, allow surgeons to manipulate the thread efficiently, reducing operative time and tissue trauma.[23] Manufacturing of surgical suture threads involves extrusion or weaving processes followed by rigorous sterilization to achieve a sterility assurance level of at least 10^{-6}, ensuring no viable microorganisms remain. Common sterilization methods include ethylene oxide (EtO) gas, which penetrates packaging effectively for heat-sensitive materials, and gamma irradiation, a radiation-based technique using cobalt-60 sources that provides deep penetration without residues, suitable for both monofilament and polyfilament threads.[29] Post-sterilization, threads are packaged in moisture-proof, gas-permeable materials such as foil-laminated pouches or Tyvek envelopes to preserve sterility, prevent degradation, and protect against environmental contaminants until the point of use.[30] Key general properties of suture threads include their diameter, which influences strength and tissue penetration; length, typically ranging from 18 to 45 inches to accommodate various procedure depths; and color coding, where dyes or natural hues (e.g., violet for certain synthetics) aid in rapid identification during surgery.[5] These attributes are standardized to ensure consistency, with diameters inversely related to size numbering systems for precise selection. Effective knotting is vital for thread performance, with the square knot serving as a fundamental technique that involves two opposing half-hitches to achieve balanced tension and minimal slippage across most thread types. The surgeon's knot, featuring an initial double throw followed by additional single throws, enhances initial security for larger-diameter threads or high-tension closures, promoting secure approximation without compromising thread integrity.[31]Suture Materials

Absorbable sutures

Absorbable sutures are surgical threads designed to be broken down and eventually eliminated by the body through natural biological processes, providing temporary wound support until tissue healing occurs. These materials degrade primarily via two mechanisms: enzymatic degradation for natural sutures, which involves breakdown by proteolytic enzymes in body fluids, and hydrolysis for synthetic sutures, a non-enzymatic reaction where water molecules cleave the polymer chains.[32] Absorption timelines vary, with short-term options losing tensile strength in 1-2 weeks and long-term ones maintaining it for 3-6 months, allowing selection based on the required duration of wound support.[33] Natural absorbable sutures are derived from collagen sourced from the submucosa of bovine or ovine intestines, offering biodegradability through enzymatic proteolysis. Plain gut sutures, untreated forms of this material, typically retain about 50% of their tensile strength for 7-10 days before significant degradation, with complete absorption occurring over 60-70 days, making them suitable for superficial or short-term closures.[34] Chromic gut sutures are treated with chromic salts to cross-link the collagen and delay enzymatic breakdown, extending tensile strength retention to 10-21 days and complete absorption to 90-120 days, which reduces the risk of premature dissolution in inflamed tissues.[34] Fast-absorbing variants of gut sutures, often heat-treated, accelerate the process to provide tensile support for only 5-7 days with full absorption in 7-14 days, ideal for areas where minimal scarring is desired, such as facial skin.[35] Synthetic absorbable sutures, composed of polymers that undergo hydrolysis, offer more predictable degradation profiles and reduced tissue reactivity compared to natural options. Poliglecaprone 25 (Monocryl), a monofilament copolymer of glycolide and ε-caprolactone, maintains effective tensile strength for 10-14 days and achieves complete absorption in 90-120 days, commonly used for soft tissue approximation like subcutaneous layers.[36] Polyglycolic acid (Dexon), a braided multifilament homopolymer, retains 70% tensile strength at 2 weeks and is fully absorbed in 60-90 days, providing robust handling for gastrointestinal procedures.[37] Polyglactin 910 (Vicryl), a copolymer of lactide and glycolide in braided form, holds 75% tensile strength for 14 days and completes absorption in 56-70 days; its irradiated variant, Vicryl Rapid, shortens this to 10-14 days for faster resorption in external applications.[33] Polydioxanone (PDS), a monofilament polymer, sustains 50-70% tensile strength for 42 days and absorbs completely over 180 days, suitable for slow-healing sites like the abdominal wall.[38] Polyglyconate (Maxon), another monofilament copolymer of glycolide and trimethylene carbonate, similarly retains tensile strength for 42-92 days with full absorption in approximately 180 days, offering high pliability for vascular and biliary surgery.[39] The primary advantages of absorbable sutures include the elimination of suture removal procedures, reducing patient discomfort and follow-up visits, and their suitability for internal applications such as gastrointestinal, urogenital, or cardiovascular sites where retrieval is impractical.[40] However, they can elicit a localized inflammatory response due to degradation byproducts, particularly with natural types, and their strength loss may be less predictable in certain physiological conditions like infection or high metabolic activity.[41]Non-absorbable sutures

Non-absorbable sutures are surgical threads designed to provide prolonged or permanent mechanical support to tissues without degrading in the body, either remaining in situ or being removed post-healing. These materials are essential in procedures requiring long-term tensile strength, such as those involving slow-healing tissues or external closures. Unlike absorbable alternatives, they resist enzymatic and hydrolytic breakdown, encapsulating within fibrous tissue over time to minimize migration or extrusion.[23] Non-absorbable sutures are categorized into natural and synthetic types. Natural materials include silk, derived from silkworm cocoons, which offers good handling and knot security but may elicit mild tissue reactions due to its protein composition; cotton and linen, both plant-based fibers, provide similar pliability but are less commonly used today owing to higher reactivity risks. Synthetic variants dominate modern practice for their consistency and biocompatibility, encompassing nylon (polyamide), a versatile monofilament with high initial strength; polypropylene (e.g., Prolene), a hydrophobic monofilament resistant to tissue ingrowth; polyester (e.g., Ethibond), typically braided for enhanced grip; and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), prized for its inertness in vascular applications.[5][42][43][28] These sutures exhibit high tensile strength and low reactivity, maintaining over 50% of their original strength indefinitely in vivo, which suits applications in skin closure, tendon repairs, and cardiovascular surgeries like vascular grafts where durability prevents dehiscence. Braided configurations, such as polyester, excel in knot security and ease of tying, ideal for deep tissues, while monofilaments like polypropylene and nylon facilitate smooth passage through tissues with reduced drag and infection risk due to their non-porous nature.[23][5][44][28] For external applications, such as skin wounds or orthopedic fixes needing extended support, non-absorbable sutures are selected to ensure structural integrity during remodeling. In cardiovascular contexts, materials like PTFE minimize thrombogenicity and promote endothelialization. Surface-placed non-absorbable sutures are typically removed after 7-14 days to avert track marks or hypertrophic scarring, with timing adjusted by site—earlier for facial areas (3-5 days) and later for extremities.[23][45][46][47]Material properties and classifications

Surgical sutures are evaluated based on several mechanical properties that determine their performance during and after implantation. Initial tensile strength refers to the maximum load a suture can withstand before breaking under straight pull, while knot tensile strength measures the same under knotted conditions, which is critical for maintaining wound closure integrity.[48] Elasticity allows the suture to stretch and recover without permanent deformation, accommodating tissue movement and reducing breakage risk.[49] Suture memory, or the material's tendency to return to its packaged coil shape, influences handling ease; high memory can cause uncoiling resistance, complicating knot tying.[50] Biological properties also play a key role in suture compatibility with host tissues. Tissue reactivity describes the inflammatory response elicited by the material, with synthetic sutures generally provoking minimal reaction compared to natural ones, thereby supporting faster healing and lower complication rates.[13] Capillarity, the ability of multifilament sutures to wick fluids along their strands, can facilitate bacterial migration and increase infection risk in contaminated wounds.[51] Suture materials are classified by origin, structure, and standardized sizing systems to ensure consistency and performance. Natural sutures derive from biological sources such as animal collagen or silk, while synthetic ones are manufactured from polymers like polyesters or polyamides, offering greater uniformity and reduced immunogenicity.[23] The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) classifies nonabsorbable sutures into three classes: Class I composed of silk or synthetic fibers of monofilament, twisted, or braided construction with diameter larger than 0.15 mm; Class II composed of multifilament silk or synthetic fibers with diameter equal to or less than 0.15 mm; Class III composed of coated multifilament metallic or synthetic fibers with diameter equal to or less than 0.15 mm, with sizes ranging from 11-0 (finest) to 7 (coarsest) defined by diameter and minimum knot-pull tensile strength.[52] In Europe, the European Pharmacopoeia (EP) and British Pharmacopoeia (BP) use a metric decimal system for thread gauge (0.01 to 10), specifying diameters and breaking loads harmonized with USP for global interoperability.[53] Recent advancements include antimicrobial-coated sutures (e.g., triclosan-impregnated polyglactin) to reduce surgical site infections and novel bioengineered materials like high-performance soluble collagen sutures for improved biocompatibility, as of 2025.[54] Additional factors enhance suture functionality and safety. Sterility assurance levels (SAL) for surgical sutures are typically set at 10^{-6}, meaning the probability of a single viable microorganism surviving sterilization is less than one in a million, achieved through methods like ethylene oxide or gamma irradiation.[10] Dyes, such as gentian violet, may be added to improve intraoperative visibility without compromising strength, though undyed options are preferred for superficial or long-term use to avoid tattooing.[23] Coatings, including calcium stearate combined with polymers like polyglactin, provide lubricity to reduce tissue drag and improve knot security in braided sutures.[55] Sutures are further categorized by filament structure: monofilament (single strand) versus polyfilament (multifilament, braided, or twisted). Monofilament sutures exhibit lower infection risk due to their smooth surface and lack of interstices for bacterial harboring, but they possess higher memory and are harder to knot securely.[23] Polyfilament sutures offer superior handling, flexibility, and knot strength from their pliable nature, though they generate more tissue drag and elevate capillarity-related infection potential.[42]Sizing and Selection

Size standards

Surgical sutures are sized according to standardized systems that specify diameter and tensile strength to ensure uniformity and reliability in clinical use. The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) system is the predominant standard in the United States, categorizing sutures from the finest (11-0) to the coarsest (7), with sizes denoted by numbers and zeros (e.g., 6-0 indicates six times finer than size 0). For collagen-based sutures, diameters range from approximately 0.07 mm for size 6-0 to 1.2 mm for size 7, while synthetic sutures have comparable but marginally narrower limits to optimize handling and knot security.[10][56] The metric sizing system, aligned with international pharmacopeias, directly measures suture diameter in millimeters (e.g., metric 0.7 corresponds to 0.07 mm for USP 6-0, and metric 1.5 for USP 5-0 at 0.15 mm) and specifies minimum tensile strength in kilograms for each size. This system facilitates global consistency, with synthetic materials often exhibiting higher strength per diameter than collagen due to their uniform structure. Representative diameter ranges for common USP sizes are shown below for synthetic sutures, which are more widely used today:| USP Size | Average Diameter (mm) | Minimum Tensile Strength (N) |

|---|---|---|

| 6-0 | 0.070–0.099 | 3.0 |

| 5-0 | 0.100–0.149 | 5.0 |

| 3-0 | 0.200–0.249 | 10.0 |

| 0 | 0.350–0.399 | 25.0 |

| 2 | 0.500–0.599 | 50.0 |

| 7 | 0.899–1.157 | 180.0 |