Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Systemd

View on Wikipedia

| systemd | |

|---|---|

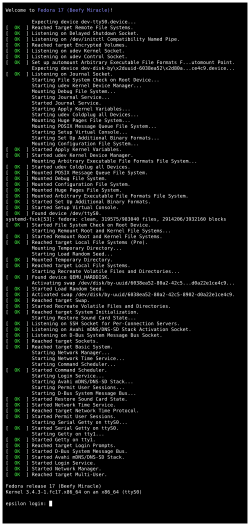

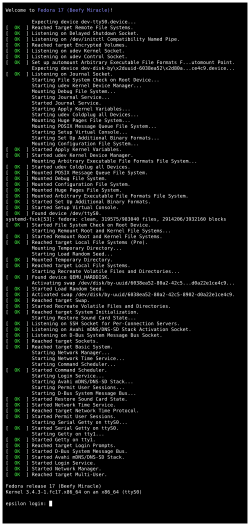

systemd startup on Fedora 17 | |

| Original author | Lennart Poettering[1] |

| Developers | Red Hat (Lennart Poettering, Kay Sievers, Harald Hoyer, Daniel Mack, Tom Gundersen, David Herrmann);[2] 345 different authors in 2018[3] and 2,032 different authors in total [4] |

| Initial release | 30 March 2010 |

| Stable release | 258.2[5] |

| Repository | |

| Written in | C |

| Operating system | Linux |

| Type | |

| License | LGPLv2.1+[6] |

| Website | systemd.io |

systemd is a software suite for system and service management on Linux[7] built to unify service configuration and behavior across Linux distributions.[8] Its main component is an init system used to bootstrap user space and manage user processes. It also provides replacements for various daemons and utilities, including device management, login management, network connection management, and event logging. The name systemd adheres to the Unix convention of naming daemons by appending the letter d,[9] and also plays on the French phrase Système D (a person's ability to quickly adapt and improvise in the face of problems).[10]

Since 2015, nearly all Linux distributions have adopted systemd. It has been praised by developers and users of distributions that adopted it for providing a stable, fast out-of-the-box solution for issues that had existed in the Linux space for years.[11][12][13] At the time of its adoption, it was the only parallel boot and init system offering centralized management of processes, daemons, services, and mount points [citation needed].

Critics of systemd contend it suffers from feature creep and has damaged interoperability across Unix-like operating systems (as it does not run on non-Linux Unix derivatives like BSD or Solaris). In addition, they contend systemd's large feature set creates a larger attack surface.[14] This has led to the development of several minor Linux distributions replacing systemd with other init systems like SysVinit or OpenRC.[15]

History

[edit]Lennart Poettering and Kay Sievers, the software engineers then working for Red Hat who initially developed systemd,[2] started a project to replace Linux's conventional System V init in 2010.[16] An April 2010 blog post from Poettering, titled "Rethinking PID 1", introduced an experimental version of what would later become systemd.[17] They sought to surpass the efficiency of the init daemon in several ways. They wanted to improve the software framework for expressing dependencies, to allow more processes to run concurrently or in parallel during system booting, and to reduce the computational overhead of the shell.

In May 2011, Fedora Linux became the first major Linux distribution to enable systemd by default, replacing Upstart. The reasoning at the time was that systemd provided extensive parallelization during startup, better management of processes and overall a saner, dependency-based approach to control of the system.[18]

In October 2012, Arch Linux made systemd the default, switching from SysVinit.[19] Developers had debated since August 2012[13] and concluded it was faster and had more features than SysVinit and that maintaining SysVinit was not worth the effort.[20] Some thought the criticism of systemd was not based on actual shortcomings of the software but rather personal dislike of Poettering and a general opposition to change. Several complaints about systemd—including its use of D-bus, C instead of bash, and an optional on-disk journal format—were instead described as advantages by the Arch maintainers.[21]

Between 2013 and 2014, the Debian Technical Committee engaged in a widely publicized debate on the mailing list about which init system to use as the default in Debian 8 before settling on systemd.[22][23][24] Soon after, Debian developer Joey Hess,[25] Technical Committee members Russ Allbery[26] and Ian Jackson,[27] and systemd package maintainer Tollef Fog Heen[28] resigned from their positions, citing the extraordinary levels of stress caused by disputes on systemd integration within the Debian and FOSS community that rendered regular maintenance virtually impossible. Mark Shuttleworth announced soon afterwards that the Debian-based Ubuntu would use systemd to replace its old Upstart init system.[29][30]

In August 2015, systemd started providing a login shell, callable via machinectl shell.[31]

In September 2016, a security bug was discovered that allowed any unprivileged user to perform a denial-of-service attack against systemd.[32] Rich Felker, developer of musl, stated that this bug reveals a major "system development design flaw".[33] In 2017 another security bug was discovered in systemd-resolved, CVE-2017-9445, which "allows disruption of service" by a "malicious DNS server".[34][35] Later in 2017, the Pwnie Awards gave author Lennart Poettering a "lamest vendor response" award due to his handling of the vulnerabilities.[36]

Design

[edit]

telephony, bootmode, dlog, and tizen service are from Tizen and are not components of systemd.[37]

systemd-nspawn.[38]Poettering describes systemd development as "never finished, never complete, but tracking progress of technology". In May 2014, Poettering further described systemd as unifying "pointless differences between distributions", by providing the following three general functions:[39]

- A system and service manager (manages both the system, by applying various configurations, and its services)

- A software platform (serves as a basis for developing other software)

- The glue between applications and the kernel (provides various interfaces that expose functionalities provided by the kernel)

systemd includes features like on-demand starting of daemons, snapshot support, process tracking[40] and Inhibitor Locks.[41] It is not just the name of the init daemon but also refers to the entire software bundle around it, which, in addition to the systemd init daemon, includes the daemons journald, logind and networkd, and many other low-level components. In January 2013, Poettering described systemd not as one program, but rather a large software suite that includes 69 individual binaries.[42] As an integrated software suite, systemd replaces the startup sequences and runlevels controlled by the traditional init daemon, along with the shell scripts executed under its control. systemd also integrates many other services that are common on Linux systems by handling user logins, the system console, device hotplugging (see udev), scheduled execution (replacing cron), logging, hostnames and locales.

Like the init daemon, systemd is a daemon that manages other daemons, which, including systemd itself, are background processes. systemd is the first daemon to start during booting and the last daemon to terminate during shutdown. The systemd daemon serves as the root of the user space's process tree; the first process (PID 1) has a special role on Unix systems, as it replaces the parent of a process when the original parent terminates. Therefore, the first process is particularly well suited for the purpose of monitoring daemons.

systemd executes elements of its startup sequence in parallel, which is theoretically faster than the traditional startup sequence approach.[43] For inter-process communication (IPC), systemd makes Unix domain sockets and D-Bus available to the running daemons. The state of systemd itself can also be preserved in a snapshot for future recall.

Core components and libraries

[edit]Following its integrated approach, systemd also provides replacements for various daemons and utilities, including the startup shell scripts, pm-utils, inetd, acpid, syslog, watchdog, cron and atd. systemd's core components include:

- systemd is a system and service manager for Linux operating systems.

- systemctl is a command to introspect and control the state of the systemd system and service manager. Not to be confused with sysctl.

- systemd-analyze may be used to determine system boot-up performance statistics and retrieve other state and tracing information from the system and service manager.

systemd tracks processes using the Linux kernel's cgroups subsystem instead of using process identifiers (PIDs); thus, daemons cannot "escape" systemd, not even by double-forking. systemd not only uses cgroups, but also augments them with systemd-nspawn and machinectl, two utility programs that facilitate the creation and management of Linux containers.[44] Since version 205, systemd also offers ControlGroupInterface, which is an API to the Linux kernel cgroups.[45] The Linux kernel cgroups are adapted to support kernfs,[46] and are being modified to support a unified hierarchy.[47]

Ancillary components

[edit]Beside its primary purpose of providing a Linux init system, the systemd suite can provide additional functionality, including the following components:

- journald

- systemd-journald is a daemon responsible for event logging, with append-only binary files serving as its logfiles. The system administrator may choose whether to log system events with systemd-journald, syslog-ng or rsyslog. The potential for corruption of the binary format has led to much heated debate.[48]

- libudev

- libudev is the standard library for utilizing udev, which allows third-party applications to query udev resources.

- localed

- localed manages the system locale and keyboard layout.

- logind

- systemd-logind is a daemon that manages user logins and seats in various ways. It is an integrated login manager that offers multiseat improvements[49] and replaces ConsoleKit, which is no longer maintained.[50] For X11 display managers the switch to logind requires a minimal amount of porting.[51] It was integrated in systemd version 30.

- hostnamed

- hostnamed manages the system hostname.

- homed

- homed is a daemon that provides portable human-user accounts that are independent of current system configuration. homed moves various pieces of data such as UID/GID from various places across the filesystem into one file,

~/.identity. homed manages the user's home directory in various ways such as a plain directory, a btrfs subvolume, a Linux Unified Key Setup volume, an fscrypt directory, or mounted from an SMB server. - networkd

- networkd is a daemon to handle the configuration of the network interfaces; in version 209, when it was first integrated, support was limited to statically assigned addresses and basic support for bridging configuration.[52][53][54][55][56] In July 2014, systemd version 215 was released, adding new features such as a DHCP server for IPv4 hosts, and VXLAN support.[57][58]

networkctlmay be used to review the state of the network links as seen by systemd-networkd.[59] Configuration of new interfaces has to be added under the /lib/systemd/network/ as a new file ending with .network extension. - resolved

- provides network name resolution to local applications

- systemd-boot

- systemd-boot is a boot manager, formerly known as gummiboot. Kay Sievers merged it into systemd with rev 220.

- systemd-bsod

- systemd-bsod is an error reporter used to generate Blue Screen of Death.

- systemd-nspawn

- systemd-nspawn may be used to run a command or OS in a namespace container.

- timedated

- systemd-timedated is a daemon that can be used to control time-related settings, such as the system time, system time zone, or selection between UTC and local time-zone system clock. It is accessible through D-Bus.[60] It was integrated in systemd version 30.

- timesyncd

- timesyncd is a client NTP daemon for synchronizing the system clock across the network.

- tmpfiles

- systemd-tmpfiles is a utility that takes care of creation and clean-up of temporary files and directories. It is normally run once at startup and then in specified intervals.

- udevd

- udev is a device manager for the Linux kernel, which handles the /dev directory and all user space actions when adding/removing devices, including firmware loading. In April 2012, the source tree for udev was merged into the systemd source tree.[61][62] In order to match the version number of udev, systemd maintainers bumped the version number directly from 44 to 183.[63]

- On 29 May 2014, support for firmware loading through udev was dropped from systemd, as it was decided that the kernel should be responsible for loading firmware.[64]

Configuration of systemd

[edit]

systemd is configured exclusively via plain-text files although GUI tools such as systemd-manager are also available.

systemd records initialization instructions for each daemon in a configuration file (referred to as a "unit file") that uses a declarative language, replacing the traditionally used per-daemon startup shell scripts. The syntax of the language is inspired by .ini files.[65]

Unit-file types[66] include:

- .service

- .socket

- .device (automatically initiated by systemd[67])

- .mount

- .automount

- .swap

- .target

- .path

- .timer (which can be used as a cron-like job scheduler[68])

- .snapshot

- .slice (used to group and manage processes and resources[69])

- .scope (used to group worker processes, not intended to be configured via unit files[70])

Adoption

[edit]| Linux distribution | Date added to software repository[a] | Enabled by default? | Date released as default | Runs without? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpine Linux | N/A (not in repository) | No | N/A | Yes |

| Android | N/A (not in repository) | No | N/A | Yes |

| Arch Linux | January 2012[71] | Yes | October 2012[72] | Although Arch provides installation instructions for OpenRC and other init systems are available in the AUR, Arch officially supports only systemd.[73][74] |

| antiX Linux | N/A (not in repository) | No | N/A | Yes |

| Artix Linux | N/A (not in repository) | No | N/A | Yes |

| CentOS | July 2014 | Yes | July 2014 (v7.0) | No |

| CoreOS | July 2013 | Yes | October 2013 (v94.0.0)[75][76] | No |

| Debian | April 2012[77] | Yes | April 2015 (v8.0)[78] | Jessie is the last release supporting installing without systemd.[79] In bullseye, a number of alternative init systems are supported |

| Devuan | N/A (not in repository) | No | N/A | Yes |

| Fedora Linux | November 2010 (v14)[80] | Yes | May 2011 (v15) | No |

| Gentoo Linux[b] | July 2011[81][83][84] | Optional[85] | N/A | Yes |

| GNU Guix System | N/A (not in repository) | No | N/A | Yes |

| Knoppix | N/A | No [86][87] | N/A | Yes |

| Linux Mint | June 2016 (v18.0) | Yes | August 2018 (LMDE 3) | No [88] |

| Mageia | January 2011 (v1.0)[89] | Yes | May 2012 (v2.0)[90] | No [91] |

| Manjaro Linux | November 2013 | Yes | November 2013 | No |

| openSUSE | March 2011 (v11.4)[92] | Yes | September 2012 (v12.2)[93] | No |

| Parabola GNU/Linux-libre | January 2012[71] | Optional[94] | N/A | Yes |

| Red Hat Enterprise Linux | June 2014 (v7.0)[95] | Yes | June 2014 (v7.0) | No |

| Slackware | N/A (not in repository) | No | N/A | Yes |

| Solus | N/A | Yes | N/A | No |

| Source Mage | June 2011[96] | No | N/A | Yes |

| SUSE Linux Enterprise Server | October 2014 (v12) | Yes | October 2014 (v12) | No |

| Ubuntu | April 2013 (v13.04) | Yes | April 2015 (v15.04) | Upstart option removed in Yaketty (16.10)[97][98][c] |

| Void Linux | June 2011, removed June 2015[99] | No | N/A | Yes |

While many distributions boot systemd by default, some allow other init systems to be used; in this case switching the init system is possible by installing the appropriate packages. A fork of Debian called Devuan was developed to avoid systemd[100][101] and has reached version 5.0 for stable usage. In December 2019, the Debian project voted in favour of retaining systemd as the default init system for the distribution, but with support for "exploring alternatives".[102]

Integration with other software

[edit]In the interest of enhancing the interoperability between systemd and the GNOME desktop environment, systemd coauthor Lennart Poettering asked the GNOME Project to consider making systemd an external dependency of GNOME 3.2.[103]

In November 2012, the GNOME Project concluded that basic GNOME functionality should not rely on systemd.[104] However, GNOME 3.8 introduced a compile-time choice between the logind and ConsoleKit API, the former being provided at the time only by systemd. Ubuntu provided a separate logind binary, but systemd became a de facto dependency of GNOME for most Linux distributions, in particular since ConsoleKit is no longer actively maintained and upstream recommends the use of systemd-logind instead.[105] The developers of Gentoo Linux also attempted to adapt these changes in OpenRC, but the implementation contained too many bugs, causing the distribution to mark systemd as a dependency of GNOME.[106][107]

GNOME has further integrated logind.[108] As of Mutter version 3.13.2, logind is a dependency for Wayland sessions.[109]

Reception

[edit]The design of systemd has ignited controversy within the free-software community. Critics regard systemd as overly complex and suffering from continued feature creep, arguing that its architecture violates the Unix philosophy. There is also concern that it forms a system of interlocked dependencies, thereby giving distribution maintainers little choice but to adopt systemd as more user-space software comes to depend on its components, which is similar to the problems created by PulseAudio, another of Lennart Poettering's projects.[110][111]

In a 2012 interview, Slackware's lead Patrick Volkerding expressed reservations about the systemd architecture, stating his belief that its design was contrary to the Unix philosophy of interconnected utilities with narrowly defined functionalities.[112] As of August 2018[update], Slackware does not support or use systemd, but Volkerding has not ruled out the possibility of switching to it.[113]

In January 2013, Lennart Poettering attempted to address concerns about systemd in a blog post called The Biggest Myths.[42]

In February 2014, musl's Rich Felker opined that PID 1 is too special to be saddled with additional responsibilities, believing that PID 1 should only be responsible for starting the rest of the init system and reaping zombie processes, and that the additional functionality added by systemd can be provided elsewhere and unnecessarily increases the complexity and attack surface of PID 1.[114]

In March 2014, Eric S. Raymond commented that systemd's design goals were prone to mission creep and software bloat.[115] In April 2014, Linus Torvalds expressed reservations about the attitude of Kay Sievers, a key systemd developer, toward users and bug reports in regard to modifications to the Linux kernel submitted by Sievers.[116] In late April 2014, a campaign to boycott systemd was launched, with a website listing various reasons against its adoption.[117][118]

In an August 2014 article published in InfoWorld, Paul Venezia wrote about the systemd controversy and attributed the controversy to violation of the Unix philosophy, and to "enormous egos who firmly believe they can do no wrong".[119] The article also characterizes the architecture of systemd as similar to that of svchost.exe, a critical system component in Microsoft Windows with a broad functional scope.[119]

In a September 2014 ZDNet interview, prominent Linux kernel developer Theodore Ts'o expressed his opinion that the dispute over systemd's centralized design philosophy, more than technical concerns, indicates a dangerous general trend toward uniformizing the Linux ecosystem, alienating and marginalizing parts of the open-source community, and leaving little room for alternative projects. He cited similarities with the attitude he found in the GNOME project toward non-standard configurations.[120] On social media, Ts'o also later compared the attitudes of Sievers and his co-developer, Lennart Poettering, to that of GNOME's developers.[121]

Forks and alternative implementations

[edit]Forks of systemd are closely tied to critiques of it outlined in the above section. Forks generally try to improve on at least one of portability (to other libcs and Unix-like systems), modularity, or size. A few forks have collaborated under the FreeInit banner.[122]

Forks of components

[edit]eudev

[edit]In 2012, the Gentoo Linux project created a fork of udev in order to avoid dependency on the systemd architecture. The resulting fork is called eudev and it makes udev functionality available without systemd.[123] A stated goal of the project is to keep eudev independent of any Linux distribution or init system.[124] In 2021, Gentoo announced that support of eudev would cease at the beginning of 2022. An independent group of maintainers have since taken up eudev.[125]

elogind

[edit]Elogind is the systemd project's "logind", extracted to be a standalone daemon. It integrates with PAM to know the set of users that are logged into a system and whether they are logged in graphically, on the console, or remotely. Elogind exposes this information via the standard org.freedesktop.login1 D-Bus interface, as well as through the file system using systemd's standard /run/systemd layout. Elogind also provides "libelogind", which is a subset of the facilities offered by "libsystemd". There is a "libelogind.pc" pkg-config file as well.[126]

Alternatives to components

[edit]ConsoleKit2

[edit]ConsoleKit was forked in October 2014 by Xfce developers wanting its features to still be maintained and available on operating systems other than Linux. While not ruling out the possibility of reviving the original repository in the long term, the main developer considers ConsoleKit2 a temporary necessity until systembsd matures.[127]

Abandoned forks

[edit]Fork of components

[edit]LoginKit

[edit]LoginKit was an attempt to implement a logind (systemd-logind) shim, which would allow packages that depend on systemd-logind to work without dependency on a specific init system.[128] The project has been defunct since February 2015.[129]

systembsd

[edit]In 2014, a Google Summer of Code project named "systembsd" was started in order to provide alternative implementations of these APIs for OpenBSD. The original project developer began it in order to ease his transition from Linux to OpenBSD.[130] Project development finished in July 2016.[131]

The systembsd project did not provide an init replacement, but aimed to provide OpenBSD with compatible daemons for hostnamed, timedated, localed, and logind. The project did not create new systemd-like functionality, and was only meant to act as a wrapper over the native OpenBSD system. The developer aimed for systembsd to be installable as part of the ports collection, not as part of a base system, stating that "systemd and *BSD differ fundamentally in terms of philosophy and development practices."[130]

notsystemd

[edit]Notsystemd intends to implement all systemd's features working on any init system.[132] It was forked by the Parabola GNU/Linux-libre developers to build packages with their development tools without the necessity of having systemd installed to run systemd-nspawn. Development ceased in July 2018.[133]

Fork including init system

[edit]uselessd

[edit]In 2014, uselessd was created as a lightweight fork of systemd. The project sought to remove features and programs deemed unnecessary for an init system, as well as address other perceived faults.[134] Project development halted in January 2015.[135]

uselessd supported the musl and μClibc libraries, so it may have been used on embedded systems, whereas systemd only supports glibc. The uselessd project had planned further improvements on cross-platform compatibility, as well as architectural overhauls and refactoring for the Linux build in the future.[136]

InitWare

[edit]InitWare is a modular refactor of systemd, porting the system to BSD platforms without glibc or Linux-specific system calls. It is known to work on DragonFly BSD, FreeBSD, NetBSD, and GNU/Linux. Components considered unnecessary are dropped.[137]

All Systems Go!

[edit]

All Systems Go! is the annual systemd conference, which is held in Berlin.[138] The main topic is systemd but other Linux areas are covered as well, like TPM, DBus, desktop environment, containers, eBPF etc.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Dates are for the general availability release.

- ^ systemd is supported in Gentoo as an alternative to OpenRC, the default init system[81] for those who "want to use systemd instead, or are planning to use Gnome 3.8 and later (which requires systemd)"[82]

- ^ Missing functionality using init systems other than systemd[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ "Lennart Poettering on systemd's Tumultuous Ascendancy". 26 January 2017. Archived from the original on 8 November 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ a b "systemd README", freedesktop.org, archived from the original on 7 July 2013, retrieved 9 September 2012

- ^ "Systemd Hits A High Point For Number Of New Commits & Contributors During 2018 - Phoronix". Archived from the original on 21 September 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ Used the "contributors" statistic from: systemd/systemd, systemd, 3 December 2023, retrieved 3 December 2023

- ^ "v258.2". 7 November 2025. Retrieved 7 November 2025.

- ^ Poettering, Lennart (21 April 2012), systemd Status Update, archived from the original on 23 April 2012, retrieved 28 April 2012

- ^ "Rethinking PID 1". 30 April 2010. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

systemd uses many Linux-specific features, and does not limit itself to POSIX. That unlocks a lot of functionality a system that is designed for portability to other operating systems cannot provide.

- ^ "InterfaceStabilityPromise". FreeDesktop.org. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ "systemd System and Service Manager". freedesktop.org. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

Yes, it is written systemd, not system D or System D, or even SystemD. And it isn't system d either. Why? Because it's a system daemon, and under Unix/Linux those are in lower case, and get suffixed with a lower case d.

- ^ Poettering, Lennart; Sievers, Kay; Leemhuis, Thorsten (8 May 2012), Control Centre: The systemd Linux init system, The H, archived from the original on 14 October 2012, retrieved 9 September 2012

- ^ "Debate/initsystem/systemd - Debian Wiki". wiki.debian.org. Archived from the original on 7 December 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ "F15 one page release notes - Fedora Project Wiki". fedoraproject.org. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ a b Gaudreault, Stéphane (14 August 2012). "Migration to systemd". arch-dev-public (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ "Freedesktop Systemd : List of security vulnerabilities". CVE Details. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ McKay, Dave (24 February 2021). "The Best Linux Distributions Without systemd". How-To Geek. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^

Simmonds, Chris (2015). "9: Starting up - the init Program". Mastering Embedded Linux Programming. Packt Publishing Ltd. p. 239. ISBN 9781784399023. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

systemd defines itself as a system and service manager. The project was initiated in 2010 by Lennart Poettering and Kay Sievers to create an integrated set of tools for managing a Linux system including an init daemon.

- ^ Lennart Poettering (30 April 2010). "Rethinking PID 1". Archived from the original on 15 January 2017. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ "F15 one page release notes", fedoraproject.org, 24 May 2001, archived from the original on 27 September 2013, retrieved 24 September 2013

- ^ "Arch Linux - News: systemd is now the default on new installations". archlinux.org. Archived from the original on 27 October 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Groot, Jan de (14 August 2012). "Migration to systemd". arch-dev-public (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 17 January 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ "Archlinux is moving to systemd (Page 2) / Arch Discussion / Arch Linux Forums". bbs.archlinux.org. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Which init system for Debian?". 5 November 2013. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ "Debian Still Debating systemd Vs. Upstart Init System". Phoronix. 30 December 2013. Archived from the original on 23 August 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ "#727708 - tech-ctte: Decide which init system to default to in Debian". 25 October 2013. Archived from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ Hess, Joey. "on leaving". Archived from the original on 16 July 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ Allbery, Russ (16 November 2014). "Resigning from the Technical Committee". debian-ctte (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 11 June 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ Jackson, Ian (19 November 2014). "Resignation". debian-ctte (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 11 June 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ Heen, Tollef Fog (16 November 2014). "Resignation from the pkg-systemd maintainer team". pkg-systemd-maintainers (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 11 June 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ "Losing graciously". 14 February 2014. Archived from the original on 8 September 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ "Quantal, raring, saucy..." 18 October 2013. Archived from the original on 28 August 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ Carroty, Paul (28 August 2015). "Lennart Poettering merged 'su' command replacement into systemd: Test Drive on Fedora Rawhide". Archived from the original on 4 September 2015.

- ^ "Assertion failure when PID 1 receives a zero-length message over notify socket #4234". GitHub. 28 September 2016. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ Felker, Rich (3 October 2016). "Hack Crashes Linux Distros with 48 Characters of Code". Kaspersky Lab. Archived from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ "CVE-2017-9445 Details", National Vulnerability Database, National Institute of Standards and Technology (U.S.), 6 July 2017, archived from the original on 6 July 2018, retrieved 6 July 2018

- ^ "CVE-2017-9445", The Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures database, The Mitre Corporation, 5 June 2017, archived from the original on 6 July 2018, retrieved 6 July 2018

- ^ "Pwnie Awards 2017, Lamest Vendor Response: SystemD bugs". Pwnie Awards. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Gundersen, Tom E. (25 September 2014). "The End of Linux". Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

It certainly is not something that comes with systemd from upstream.

- ^ "The New Control Group Interfaces". Freedesktop.org. 28 August 2015. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ Poettering, Lennart (May 2014). "A Perspective for systemd: What Has Been Achieved, and What Lies Ahead" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ^ "What is systemd?". Linode. 11 September 2019. Archived from the original on 24 January 2020. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ "Inhibitor Locks". freedesktop.org. Archived from the original on 3 May 2020. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ a b Poettering, Lennart (26 January 2013). "The Biggest Myths". Archived from the original on 17 October 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "Debate/initsystem/systemd – Debian Documentation". Debian. 2 January 2014. Archived from the original on 7 December 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ^ Edge, Jake (7 November 2013). "Creating containers with systemd-nspawn". LWN.net. Archived from the original on 23 August 2014. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ "ControlGroupInterface". freedesktop.org. Archived from the original on 12 December 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ^ Heo, Tejun (28 January 2014). "cgroup: convert to kernfs". linux-kernel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ^ Heo, Tejun (13 March 2014). "cgroup: prepare for the default unified hierarchy". linux-kernel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ^ "systemd's binary logs and corruption". 17 February 2014. Archived from the original on 11 May 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ "systemd-logind.service". freedesktop.org. Archived from the original on 11 April 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ^ "ConsoleKit official website". freedesktop.org. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ^ "How to hook up your favorite X11 display manager with systemd". freedesktop.org. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ "Networking in +systemd - 1. Background". 27 November 2013. Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Networking in +systemd - 2. libsystemd-rtnl". 27 November 2013. Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Networking in +systemd - 3. udev". 27 November 2013. Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Networking in +systemd - 4. networkd". 27 November 2013. Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Networking in +systemd - 5. the immediate future". 27 November 2013. Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ Larabel, Michael (4 July 2014). "systemd 215 Works On Factory Reset, DHCPv4 Server Support". Archived from the original on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ^ Šimerda, Pavel (3 February 2013). "Can Linux network configuration suck less?".

- ^ – Linux User Manual – User Commands from Manned.org

- ^ "timedated". freedesktop.org. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ^ Sievers, Kay. "The future of the udev source tree". vger.kernel.org/vger-lists.html#linux-hotplug linux-hotplug (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ Sievers, Kay, "Commit importing udev into systemd", freedesktop.org, archived from the original on 20 April 2013, retrieved 25 May 2012

- ^ Proven, Liam. "Version 252 of systemd released". The Register. Archived from the original on 5 November 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ "[PATCH] Drop the udev firmware loader". systemd-devel (Mailing list). 29 May 2014. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ "systemd.syntax". www.freedesktop.org. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ "systemd.unit man page". freedesktop.org. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ "systemd.device". www.freedesktop.org. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ "systemd Dreams Up New Feature, Makes It Like Cron". Phoronix. 28 January 2013. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ^ "systemd.slice (5) - Linux Man Pages". Archived from the original on 19 February 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

... a slice ... is a concept for hierarchically managing resources of a group of processes.

- ^ "systemd.scope". FreeDesktop.org. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Git clone of the 'packages' repository". Web interface to the Arch Linux git repositories. 12 January 2012. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ "systemd is now the default on new installations". Arch Linux. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- ^ "OpenRC - ArchWiki". wiki.archlinux.org. Retrieved 21 July 2025.

- ^ "init - ArchWiki". wiki.archlinux.org. Retrieved 21 July 2025.

- ^ "coreos/manifest: Releases: v94.0.0". github.com. 3 October 2013. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ "CoreOS's init system", coreos.com, archived from the original on 14 February 2014, retrieved 14 February 2014

- ^ "systemd". debian.org. Archived from the original on 29 December 2014. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

- ^ Garbee, Bdale (11 February 2014). "Bug#727708: call for votes on default Linux init system for jessie". debian-ctte (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ "systemd - system and service manager". Debian Wiki. Installing without systemd. Archived from the original on 4 April 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ "Fedora 14 talking points". Archived from the original on 9 June 2015. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ a b "systemd", wiki.gentoo.org, archived from the original on 12 October 2012, retrieved 26 August 2012

- ^ "Installing the Gentoo Base System § Optional: Using systemd". Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- ^ "Comment #210 (bug #318365)", gentoo.org, archived from the original on 16 February 2015, retrieved 5 July 2011

- ^ "systemd", gentoo.org, archived from the original on 26 June 2011, retrieved 5 July 2011

- ^ "Downloads – Gentoo Linux".

- ^ "KNOPPIX 7.4.2 Release Notes". Archived from the original on 6 January 2018. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

...script-based KNOPPIX system start with sysvinit

- ^ "KNOPPIX 8.0 Die Antwort auf Systemd (German)". Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

...Knoppix 'boot process continues to run via Sys-V init with few bash scripts that start the system services efficiently sequentially or in parallel. (The original German text: Knoppix' Startvorgang läuft nach wie vor per Sys-V-Init mit wenigen Bash-Skripten, welche die Systemdienste effizient sequenziell oder parallel starten.)

- ^ "LM Blog: both Mint 18 and LMDE 3 will switch to systemd". 10 April 2015. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ ChangeLog of Mageia's systemd package, archived from the original on 28 March 2016, retrieved 19 March 2016

- ^ Scherschel, Fabian (23 May 2012), Mageia 2 arrives with GNOME 3 and systemd, The H, archived from the original on 8 December 2013, retrieved 22 August 2012

- ^ "Mageia forum • View topic - is it possible to replace systemd?". Archived from the original on 19 February 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ Directory view of the 11.4 i586 installation showing presence of the systemd v18 installables, 23 February 2011, archived from the original on 28 September 2013, retrieved 24 September 2013

- ^ "OpenSUSE: Not Everyone Likes systemd". Phoronix. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

The recently released openSUSE 12.2 does migrate from SysVinit to systemd

- ^ "Parabola ISO Download Page". Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ^ Red Hat Unveils Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7, 10 June 2014, archived from the original on 14 July 2014, retrieved 19 March 2016

- ^ "Initial entry of the "systemd" spell". Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ "Ubuntu Wiki: Switching init systems". Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ^ "Linked packages : upstart". Launchpad. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ "Void-Package: systemd: removed; no plans to resurrect this". GitHub. Archived from the original on 19 February 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ "Meet Devuan, the Debian fork born from a bitter systemd revolt". Archived from the original on 9 December 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ Sharwood, Simon (5 May 2017). "systemd-free Devuan Linux hits RC2". The Register. Archived from the original on 5 May 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ "Debian Developers Decide On Init System Diversity: "Proposal B" Wins". Phoronix. Archived from the original on 28 December 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ Poettering, Lennart (18 May 2011). "systemd as an external dependency". desktop-devel (Mailing list). GNOME. Archived from the original on 27 May 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ^ Peters, Frederic (4 November 2011). "20121104 meeting minutes". GNOME release-team (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 7 September 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ^ "ConsoleKit". Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

ConsoleKit is currently not actively maintained. The focus has shifted to the built-in seat/user/session management of Software/systemd called systemd-logind!

- ^ Vitters, Olav (25 September 2013). "GNOME and logind+systemd thoughts". Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ "GNOME 3.10 arrives with experimental Wayland support". ZDNet. Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ "GNOME initiatives: systemd". Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ "Mutter 3.13.2: launcher: Replace mutter-launch with logind integration". 19 May 2014. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ Vaughan-Nichols, Steven (19 September 2014). "Linus Torvalds and others on Linux's systemd". ZDNet. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 25 February 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ "1345661 - PulseAudio requirement breaks Firefox on ALSA-only systems". Bugzilla. Mozilla. 3 September 2021. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ "Interview with Patrick Volkerding of Slackware". linuxquestions.org. 7 June 2012. Archived from the original on 3 May 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ^ "I'm back after a break from Slackware: sharing thoughts and seeing whats new!". linuxquestions.org. Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ Rich Felker (9 February 2014). "Broken by design: systemd". Archived from the original on 23 October 2019.

- ^ "Interviews: ESR Answers Your Questions". Slashdot.org. 10 March 2014. Archived from the original on 22 March 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ^ Torvalds, Linus (2 April 2014). "Re: [RFC PATCH] cmdline: Hide "debug" from /proc/cmdline". linux-kernel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ^ "Is systemd as bad as boycott systemd is trying to make it?". LinuxBSDos.com. 3 September 2014. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ "Boycott systemd.org". Archived from the original on 6 May 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ a b Venezia, Paul (18 August 2014). "systemd: Harbinger of the Linux apocalypse". Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ "Linus Torvalds and others on Linux's systemd". ZDNet. Archived from the original on 20 November 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ "A realization that I recently came to while discussing the whole systemd..." 31 March 2014. Archived from the original on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ^ "FreeInit.org". www.freeinit.org. Archived from the original on 1 August 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ "eudev/README". GitHub. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ "Gentoo eudev project". Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ Basile, Anthony G. (24 August 2021). "eudev retirement on 2022-01-01". Repository news items. Gentoo Linux. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ^ "elogind/README". GitHub. Archived from the original on 19 February 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- ^ Koegel, Eric (20 October 2014). "ConsoleKit2". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ "loginkit/README". GitHub. Archived from the original on 19 February 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ^ "dimkr/LoginKit (Github)". GitHub. Archived from the original on 19 February 2023. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ^ a b "GSoC 2014: systemd replacement utilities (systembsd)". OpenBSD Journal. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ projects / systembsd.git / summary, archived from the original on 9 July 2018, retrieved 8 July 2018

- ^ Luke Shumaker (17 June 2017). "notsystemd v232.1 release announcement". Dev@lists.parabola.nu (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "notsystemd". Parabola GNU/Linux-libre. Archived from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ Larabel, Michael (21 September 2014). "Uselessd: A Stripped Down Version Of systemd". Phoronix. Archived from the original on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ "Uselessd is dead". Uselessd website. Archived from the original on 16 May 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ "uselessd :: information system". uselessd.darknedgy.net. Archived from the original on 16 May 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ "InitWare/InitWare: The InitWare Suite of Middleware allows you to manage services and system resources as logical entities called units. Its main component is a service management ("init") system". GitHub. 14 November 2021. Archived from the original on 1 August 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Team, All Systems Go!. "All Systems Go!". All Systems Go!. Retrieved 29 August 2025.

External links

[edit]Systemd

View on GrokipediaHistory

Conception and Early Development

Systemd originated from discussions between Lennart Poettering, a developer at Red Hat, and Kay Sievers, then at Novell, who outlined its core concepts—initially under the working name "Babykit"—during a flight returning from the 2009 Linux Plumbers Conference.[6] The initiative aimed to address longstanding deficiencies in Linux initialization systems, such as the serial execution and dependency resolution limitations of SysV init, which led to prolonged boot times and inefficient service management, as well as shortcomings in alternatives like Upstart, including poor dependency handling and licensing constraints.[7] Poettering and Sievers sought a unified, event-driven approach leveraging socket activation for on-demand service startup, parallel processing via cgroups for resource supervision, and reduced reliance on shell scripts to minimize overhead and errors.[8] On April 30, 2010, Poettering publicly proposed systemd in his blog post "Rethinking PID 1," advocating for PID 1 to serve as a sophisticated process manager capable of parallelizing service activation, integrating D-Bus for inter-process communication, and employing filesystem autofs for concurrent mounting, drawing inspiration from macOS's launchd while adapting to Linux's kernel features like control groups.[8] This marked the formal conception, emphasizing empirical improvements in boot performance—targeting reductions from minutes to seconds through maximized parallelism—and causal dependencies modeled explicitly rather than via brittle scripts.[8] The proposal critiqued existing systems' inability to handle modern hardware dynamics, such as hotplug events, without manual intervention. Early development ensued rapidly under Poettering's lead at Red Hat, with Sievers contributing significantly to core implementations, alongside Harald Hoyer and others from SUSE, Intel, and Nokia.[8] Experimental code was made available via a public Git repository shortly after the announcement, enabling initial testing on development systems and virtual machines, though limited to minimal validation due to its nascent state.[8] The focus was on prototyping key innovations, including socket-based and D-Bus-triggered activation to decouple service readiness from boot sequencing, and integrating with existing tools like udev for device management, setting the stage for broader evaluation before distribution integration.[8] By late 2010, prototypes demonstrated viability for replacing SysV init in enterprise environments, prioritizing reliability over completeness.[6]Widespread Adoption and Key Milestones

systemd was initially released on March 30, 2010, by developers Lennart Poettering and Kay Sievers at Red Hat.[9][3] Fedora adopted systemd as its default init system with Fedora 15, released on May 24, 2011, marking the first major Linux distribution to integrate it and replace Upstart.[10][11] This early adoption by Fedora, sponsored by Red Hat, facilitated systemd's development and testing in a production environment.[12] Subsequent integrations accelerated in 2012, with Arch Linux and openSUSE switching to systemd as their primary service manager, enabling parallel boot processes and socket activation features.[13] By 2014, Debian's technical committee voted to adopt systemd following internal debates, implementing it as the default in Debian 8 (Jessie), released on April 26, 2015.[14][15] Ubuntu followed suit, transitioning from Upstart to systemd in Ubuntu 15.04 (Vivid Vervet), released on April 23, 2015, after an announcement in February 2014.[16][17] These milestones propelled systemd's dominance; by mid-2015, it had supplanted SysVinit across most prominent distributions, including derivatives like CentOS and RHEL, powering over 90% of Linux server and desktop deployments due to its efficiency in service management and dependency handling.[18][12] Adoption continued with minor distributions and embedded systems, solidifying systemd's role in unifying Linux initialization despite ongoing debates over its scope.[19]Recent Evolution and Releases

Systemd 257, released in December 2024, introduced support for Multipath TCP in socket units, enabling more robust network connectivity options, and added thePrivatePIDs= directive to allow processes to run as PID 1 within their own PID namespace for enhanced isolation.[20] It also deprecated System V service script support, signaling a shift away from legacy init compatibility, and disabled cgroup v1 by default (requiring an environment variable to re-enable), with full removal planned for the subsequent version.[20] New tools included systemd-sbsign for Secure Boot EFI binary signing, alongside refinements like reworked systemd-tmpfiles --purge behavior limited to specific flagged lines.[20]

The subsequent systemd 258, released on September 17, 2025, fully removed cgroup v1 support and raised the minimum supported Linux kernel version to 5.4, aligning with modern hardware and security standards while dropping compatibility for older systems.[21] [22] Key additions encompassed new utilities such as systemd-factory-reset for initiating a factory reset on reboot and systemd-pty-forward for secure pseudo-TTY allocation, alongside the ability to embed UEFI firmware images directly into Unified Kernel Images (UKIs).[21] Security enhancements included default 0600 permissions for TTY/PTS devices, PID file descriptors for logind session tracking, and exclusive reliance on OpenSSL as the cryptographic backend, eliminating alternative TLS options.[22] System V style controls and the SystemdOptions EFI variable were also excised.[22]

These releases reflect systemd's ongoing evolution toward stricter security postures, reduced legacy overhead, and integration with contemporary Linux kernel capabilities, with v259 anticipated to eliminate remaining System V service script support entirely.[21] Maintenance releases, such as v257.10 in October 2025, have focused on bug fixes and stability without major feature additions.[23] The project's cadence of roughly semiannual major updates continues to drive refinements in service management, resource control, and boot efficiency across adopting distributions.[23]

Design and Architecture

Foundational Principles

systemd's foundational principles center on replacing the sequential, script-based limitations of traditional SysVinit systems with a unified, Linux-optimized framework for initializing and managing userspace services as PID 1. Developed primarily by Lennart Poettering and Kay Sievers, it prioritizes leveraging kernel-specific capabilities such as control groups (cgroups) for precise process tracking and resource isolation, moving beyond unreliable PID files used in older init systems.[24] This approach ensures robust supervision, where systemd monitors service processes directly via cgroups, enabling automatic restarts and failure detection without external dependencies.[25] A core tenet is aggressive parallelization of boot tasks, allowing independent services to activate concurrently based on dependencies rather than fixed scripts, which reduces boot times from minutes to seconds in many configurations—Fedora 15, the first major adopter in May 2011, demonstrated boot reductions to under 5 seconds for basic targets.[24] Dependency handling employs a transactional model with directives likeAfter= and Requires=, resolving cycles and queuing jobs to maintain system integrity during state changes.[25] Event-driven activation mechanisms—encompassing socket, D-Bus, path, device, and timer events—facilitate on-demand service startup, conserving resources by deferring non-essential daemons until invoked, reviving and extending Unix socket activation concepts for modern scalability.[24][1]

Standardization forms another pillar, with portable unit files describing services uniformly across distributions, mitigating the fragmentation of ad-hoc shell scripts and enabling upstream developers to target a consistent interface.[24] Integration with security modules like SELinux and PAM, alongside features such as automounting and runtime directory management, underscores a philosophy of holistic system bootstrapping, where disparate tools are consolidated into a cohesive suite without sacrificing modularity.[25] This design emphasizes predictability and reproducibility, unloading inactive units to minimize memory footprint and ensuring clean shutdowns through cgroup freezing, addressing empirical inefficiencies in legacy systems where services often lingered post-failure.[1]

Core Components

The core of systemd comprises the central init process and a set of integrated daemons that handle essential system functions such as logging, device management, and user sessions, replacing disparate traditional tools with a unified framework. These components operate as services managed by systemd itself, leveraging D-Bus for inter-process communication and cgroups for resource control.[26] systemd, running as PID 1, acts as the primary system and service manager. It bootstraps the user space during boot, parallelizes service startup based on dependency graphs defined in unit files, and supports activation mechanisms like socket listening and D-Bus requests to minimize idle processes. Additionally, it oversees mounts, automounts, and process trees via cgroups, ensuring fault isolation and resource limits.[25][1] systemd-journald functions as the logging subsystem, aggregating messages from the kernel, early boot stages, stdout/stderr of services, and audit logs into a binary, indexed format stored in /var/log/journal. This enables structured querying with tools like journalctl, persistent storage across reboots, and forwarding to external syslog daemons, improving on traditional rsyslog or syslog-ng by capturing pre-daemon logs.[2] systemd-logind oversees user authentication and session lifecycle, tracking logged-in users, graphical and console sessions, and multi-seat configurations. It handles events like lid closures for power management, inhibits shutdowns during active sessions, and provides D-Bus methods for session queries, facilitating integration with display managers like GDM.[2] systemd-logind also manages inhibition of various system actions, including "sleep" (suspend-to-RAM), to prevent interruptions during active sessions or operations. Active inhibitors are displayed bysystemd-inhibit --list, where the "What" column specifies the inhibited action; suspend is blocked only if "sleep" appears in this column for at least one inhibitor. In the absence of a "sleep" inhibitor, suspend proceeds normally. Failures or hangs during suspend are typically attributable to hardware, driver (such as proprietary graphics drivers), kernel modules, or firmware issues rather than inhibition status. Diagnostic logs are available via journalctl -b -1 -u systemd-suspend.service or dmesg.[27][28][29]

systemd-udevd manages dynamic device handling by processing kernel uevents, creating /dev entries, and applying udev rules for permissions, symlinks, and ownership. As a systemd-native service, it benefits from dependency-aware startup, enabling faster boot times compared to the independent udev daemon it supersedes.[26]

Supporting these are daemons like systemd-timedated for NTP synchronization and timezone adjustments via timedatectl, systemd-hostnamed for dynamic hostname changes, and systemd-localed for locale and keyboard layout management, all exposing user-friendly command-line interfaces while maintaining declarative configurations.[25]

Ancillary Tools and Libraries

libsystemd serves as the principal library for applications seeking to interface with systemd's capabilities, encompassing APIs for service notification, D-Bus communication, and resource management interactions. It includes modules such as sd-daemon for enabling daemons to signal readiness to the systemd manager via file descriptors and sd_notify for protocol-based notifications.[30] A prominent subset is sd-bus, an asynchronous D-Bus client library integrated into libsystemd, designed for efficient inter-process communication without reliance on higher-level bindings. Stabilized in systemd version 221 on October 31, 2015, sd-bus supports both system and user bus connections, method calls, signal handling, and property access, prioritizing minimal dependencies and direct socket usage over the full D-Bus library.[31] [32] [33] Ancillary tools complement these libraries by providing diagnostic and introspection utilities. systemd-analyze inspects boot performance metrics, including time-to-ready measurements and dependency graphs via commands likeblame for unit activation durations and critical-chain for sequential startup paths.[34] busctl facilitates D-Bus introspection, enabling enumeration of services, objects, interfaces, and properties on connected buses, as well as direct method invocation for testing.

Additional utilities include journalctl for retrieving and filtering binary logs from systemd-journald, supporting queries by time, priority, unit, or identifier with options for real-time tailing and output formatting.[35] These tools, distributed within systemd packages, enhance developer and administrator workflows by leveraging libsystemd APIs for programmatic access where command-line interaction suffices for ad-hoc analysis.[36]

Features and Functionality

Service Management and Units

In systemd, units represent the fundamental resources managed by the system and service manager, including processes, filesystems, network sockets, and other system objects. Each unit is defined by a configuration file in INI-style format, typically with a filename suffix indicating its type, such as .service for process supervision or .socket for network listeners. These files encode dependencies, activation conditions, and runtime behavior, enabling declarative management over imperative scripting used in predecessors like SysV init.[37] Systemd supports 11 unit types: service, socket, target, device, mount, automount, swap, timer, path, slice, and scope. Service units specifically handle the starting, stopping, and supervision of daemon processes, tracking their main process ID (PID) for reliable state management and automatic restarts if configured. Socket units activate services on-demand via incoming connections, reducing idle resource usage, while target units group other units into milestones like multi-user.target for boot phases. Slices and scopes manage resource allocation via cgroups, enforcing limits on CPU, memory, and I/O for services.[38][39] Service management occurs primarily through the systemctl command-line tool, which introspects unit states, issues control operations, and queries dependencies. Common operations includesystemctl start <unit> to launch a service, systemctl stop <unit> to terminate it, systemctl enable <unit> to link it for automatic startup at boot via symlinks in /etc/systemd/system/, and systemctl status <unit> to display runtime details like active state, logs, and PIDs. Enabling persists across reboots by installing wanted-by links to targets, while masking units prevents activation entirely. Systemd reloads configurations dynamically with systemctl daemon-reload after editing unit files, ensuring changes take effect without full restarts.[40]

Unit files are stored hierarchically: vendor-provided in /usr/lib/systemd/ (immutable), administrator overrides in /etc/systemd/system/, and transient runtime units generated in /run/systemd/. A typical service unit file structure includes a [Unit] section for metadata like Description, After/Before dependencies, and Wants/Requires for orchestration; a [Service] section with Type (e.g., simple for forking daemons, notify for readiness signals), ExecStart for the command, Restart directives, and cgroup limits; and an [Install] section with WantedBy for enabling. Drop-in overrides in /etc/systemd/system/Per-User Instances

systemd supports per-user instances of the service manager, enabling users to manage their own services, timers, sockets, paths, and other units independently of the system instance viasystemctl --user. The per-user manager typically starts automatically upon graphical login or certain PAM sessions that set up the necessary environment. However, in non-interactive sessions (such as SSH logins, cron jobs, or boot-time scripts) or without a graphical/PAM-triggered login, the per-user manager may not be running, leading to errors when invoking systemctl --user, such as "systemctl --user unavailable", "unknown error", or "Failed to connect to bus: No such file or directory".[40]

To ensure the per-user manager runs persistently—starting at boot and continuing after logout—enable lingering for the user by executing loginctl enable-linger $USER (run as the user, without superuser privileges). This configuration starts the user manager at boot and maintains it indefinitely. After enabling lingering, reload the user configuration with systemctl --user daemon-reload and then enable/start desired user services (e.g., systemctl --user enable --now example.service). Verify successful connection with systemctl --user status.[41]

Additional causes of connection failures include an unset or incorrect XDG_RUNTIME_DIR (which should be /run/user/$(id -u)); if unset, log out and log in again or source the shell profile to restore it. On minimal installations or containers, ensure the dbus-user-session package is installed and that systemd-logind is active. This behavior is standard in systemd and is especially relevant for headless systems like Raspberry Pi, where background or always-on user services are common.[42][43]

Boot Process and Resource Control

Systemd initializes the Linux system as process ID 1 (PID 1), replacing traditional init systems by parsing unit files to construct a dependency graph for services, sockets, mounts, and other resources.[25] It activates units in parallel when dependencies permit, leveraging modern multi-core processors to execute independent startup tasks concurrently, such as mounting filesystems and launching daemons, rather than sequentially as in SysV init.[25] This parallelization, introduced with systemd's release on March 30, 2010, has empirically reduced boot times; for instance, early adopters like Fedora 15 reported boot durations dropping from over 20 seconds to under 10 seconds in multi-user mode compared to prior init systems.[44] The boot sequence progresses through targets—special units akin to runlevels—starting from sysinit.target for core system initialization (e.g., udev settlement, local-fs.target), advancing to basic.target, then multi-user.target for networked services, and optionally graphical.target.[45] Dependencies are declared via directives likeAfter=, Requires=, and Wants=, ensuring ordered activation while maximizing parallelism; for example, network-independent services start immediately without awaiting network-online.target.[37] Systemd also handles first-boot setup, generating machine-id and applying unit presets automatically.[37] Tools like systemd-analyze quantify boot performance by timing critical chain paths and individual units, aiding optimization.[34]

For resource control, systemd integrates with Linux control groups (cgroups) to enforce limits on CPU, memory, I/O, and device access for unit-managed processes, organizing them into hierarchical slices, scopes, and services.[46] Directives in unit files, such as MemoryMax=, CPUQuota=, and IOWeight=, apply these controls; for example, MemoryMax=500M caps a service's RAM usage, preventing system-wide exhaustion.[46] Systemd supports both cgroups v1 (via controllers like cpu, memory) and the unified cgroups v2 hierarchy, enabled via kernel boot parameters like systemd.unified_cgroup_hierarchy=1, which delegates resource delegation to child controllers for finer-grained management.[47] In cgroups v2 mode, adopted by default in distributions like RHEL 8 onward when configured, systemd binds the unit tree to cgroup paths (e.g., /system.slice/[httpd](/page/Httpd).service), enabling automatic enforcement and monitoring without manual cgroup manipulation.[48] This integration allows slicing resources across user sessions (user.slice) and system services (system.slice), with empirical benefits in container orchestration and multi-tenant environments by isolating workloads and averting resource contention.[46]

Logging and System Monitoring

systemd-journald serves as the primary logging daemon, collecting and storing log data from multiple sources including the kernel via kmsg, traditional syslog messages, the native Journal API, stdout and stderr streams from services, and audit subsystem records.[49] Logs are maintained in a structured, indexed binary format with metadata fields supporting up to 2⁶⁴-1 bytes each, enabling efficient querying without reliance on external text parsers.[49] This approach replaces fragmented syslog-based systems by centralizing logs under a unified namespace, with support for isolated journal namespaces to separate log streams for different environments.[49] Storage occurs either persistently in/var/log/journal—requiring the directory's existence and configuration—or volatalily in /run/log/journal, where data is discarded on reboot.[49] Automatic vacuuming manages disk usage by discarding old or oversized entries, eliminating manual rotation typical in legacy systems.[49] Configuration is handled via /etc/systemd/journald.conf (introduced in systemd version 206), allowing options like forwarding logs to syslog, console, or wall, with kernel command-line overrides available since version 186.[49] Integration supports tools like systemd-cat for piping application output into the journal and credential passing for enhanced security since version 256.[49]

The journalctl command provides querying and display capabilities for journal logs, supporting filters by unit (-u), boot ID (-b), priority (-p), time ranges (--since, --until), or custom fields with AND/OR logic.[50] Output formats include short, verbose (showing all fields with -a), JSON, or export formats for interoperability, with real-time monitoring via --follow (-f) for ongoing log tailing.[50] This enables troubleshooting by correlating events across system components, such as service failures or kernel issues, with cursor-based navigation for precise log positioning.[50]

For system monitoring, systemd-analyze examines boot performance, reporting aggregate times for kernel, initrd, and userspace phases (e.g., via systemd-analyze time), unit-specific initialization delays (systemd-analyze blame), and dependency chains (systemd-analyze critical-chain).[51] It generates SVG plots of timelines for visual analysis of service startups.[51] Complementing this, systemd-cgtop offers real-time views of control group (cgroup) resource consumption, ranking by CPU (scaled to processor count, e.g., up to 800% on 8 cores), memory, or I/O, updating every second in a top-like interface.[52] Accurate metrics require enabling MemoryAccounting= and IOAccounting= in unit files, facilitating identification of resource-intensive processes or slices.[52] These tools leverage systemd's cgroup integration for granular oversight without external dependencies.[52]

Configuration and Customization

Unit File Syntax and Directives

Unit files employ an INI-style syntax, consisting of sections denoted by headers in square brackets, such as[Unit], followed by directives in the form Key=Value. Whitespace surrounding the equals sign is ignored, and lines may be concatenated using a backslash at the end, which is replaced by a space in the resulting value. Comments begin with a semicolon or hash mark and are ignored, while empty lines serve for readability and are disregarded during parsing. Boolean values accept strings like yes, true, on, 1 for affirmative and no, false, off, 0 for negative; other values may lead to errors depending on the directive. Values can be quoted with single or double quotes to include spaces or special characters, supporting C-style escapes such as \n for newlines. Line length is capped at 1 MB to prevent parsing issues.[53]

Unit files reside in hierarchical directories including /etc/systemd/system/ for local overrides, /run/systemd/system/ for runtime configurations, and /usr/lib/systemd/system/ (or /lib/systemd/system/) for vendor-supplied defaults, with earlier paths taking precedence over later ones. Filenames follow the pattern unit-name.extension, where the extension indicates the unit type (e.g., .service, .socket), limited to 255 characters; template units use @ for instantiation, as in [email protected]. Sections include the universal [Unit] for general properties and dependencies, [Install] for enabling behavior, and type-specific sections like [Service] for service units. Directives in [Unit] are evaluated at runtime, while those in [Install] apply during systemctl enable. Drop-in overrides in subdirectories like unit-name.d/*.conf allow partial modifications without altering originals, processed in lexicographic order.[37]

The [Unit] section defines core attributes and inter-unit relationships. Key directives include:

| Directive | Description |

|---|---|

Description= | Provides a short, human-readable summary of the unit's purpose.[37] |

Documentation= | Lists URIs (e.g., man:, http://) for further references, space-separated.[37] |

Requires= | Establishes a strong dependency, requiring listed units to start successfully before this one; failure propagates.[37] |

Wants= | Imposes a weak dependency, attempting to start listed units but continuing on failure.[37] |

After= / Before= | Specifies ordering: this unit starts after (or before) listed units during activation, and reverses for deactivation.[37] |

Conflicts= | Prevents concurrent activation with listed units, triggering stops if violated.[37] |

[Unit] section might appear as:

[Unit]

Description=Example Service

Documentation=man:example(1)

Requires=network.target

After=network.target

Wants=example-data.service

[Unit]

Description=Example Service

Documentation=man:example(1)

Requires=network.target

After=network.target

Wants=example-data.service

[Install] section governs installation via symlinks created by systemctl enable. Notable directives are:

| Directive | Description |

|---|---|

WantedBy= | On enable, generates symlinks in the .wants/ subdirectory of specified targets (e.g., multi-user.target.wants/).[37] |

RequiredBy= | Similar to WantedBy but uses .requires/, enforcing strong dependencies.[37] |

Alias= | Defines additional names as symlinks upon enabling, allowing activation under aliases.[37] |

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

Alias=example-alias.service

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

Alias=example-alias.service

%i for template instances or %H for hostname, enabling dynamic configuration. Multiple assignments to the same key may append to lists or override prior values, per directive semantics.[37]

Runtime Management Commands

The primary interface for runtime management in systemd is thesystemctl command, which enables administrators to introspect the current state of units and control their activation, deactivation, and reloading without requiring a system reboot.[40] This tool operates by issuing D-Bus method calls to the systemd manager process (PID 1), allowing precise manipulation of services, sockets, targets, and other unit types during system operation.[40] Unlike legacy init systems, systemctl supports parallel operations and dependency resolution, reducing administrative overhead for dynamic environments.[25]

Key subcommands for unit control include:

start: Immediately activates a unit and its dependencies, transitioning it to an active state if possible; for example,systemctl start [nginx](/page/Nginx).servicelaunches the specified service.[40]stop: Deactivates a unit, stopping its processes and reversing dependencies; this command waits for clean shutdown unless--forceis specified.[40]restart: Equivalent to stopping followed by starting a unit, useful for applying configuration changes without manual sequencing.[40]reload: Requests a unit to reload its configuration without interrupting running processes, applicable to units supporting reload signals like daemons with SIGHUP handling.[40]status: Displays detailed runtime information for a unit, including PID, resource consumption, and recent log excerpts from the journal.[40]

list-units enumerates all loaded units with their states (active, inactive, failed), while show retrieves all properties of a specific unit in key-value format, facilitating scripting and debugging.[40] The daemon-reload command rescans unit files after modifications, reloading configuration into the manager without affecting running units, ensuring consistency during live updates.[40]

Transient units can be managed via systemd-run, which spawns ephemeral services or scopes for one-off tasks, assigning them properties like CPU limits or nice priorities at invocation; for instance, systemd-run --scope -p CPUQuota=50% command executes with resource constraints.[54] This complements systemctl by enabling ad-hoc runtime isolation without persistent unit files.[54] Control group monitoring is available through systemd-cgtop, which provides a top-like view of cgroups sorted by resource usage (CPU, memory, I/O), aiding in identifying resource-intensive units.[55]

Adoption and Integration

Distribution-Level Implementation

Linux distributions implement systemd by packaging its components—typically as a core set of binaries, libraries, and tools—into their repositories, configuring the bootloader (e.g., GRUB) to invoke/lib/systemd/systemd as process ID 1 via kernel parameters like init=/lib/systemd/systemd if necessary, and generating initramfs images with systemd support using tools such as dracut (in Red Hat derivatives) or mkinitcpio (in Arch Linux). Service management transitions involve converting legacy SysV init scripts to native unit files or using compatibility generators like sysv-generator, with distribution-specific units placed in /usr/lib/systemd/system/ or /lib/systemd/system/ and overrides in /etc/systemd/system/. Presets in /usr/lib/systemd/system-preset/ dictate default service enablement, often customized per distro to enable essential services like networking while disabling others.[56]

Distributions contribute variably to upstream development; for instance, Red Hat employees, including systemd's creators Lennart Poettering and Kay Sievers, drive features aligned with enterprise needs, such as robust resource control in RHEL. Packaging differences arise from formats—RPM for Fedora/RHEL/openSUSE, DEB for Debian/Ubuntu—and integrations, like Ubuntu's compatibility with AppArmor or Arch's emphasis on minimalism with user-managed units. Backports and patches address stability or feature gaps, while tools like systemd-analyze aid boot optimization tailored to hardware or use cases.[57]

| Distribution | First Version with Default systemd | Release Date | Key Implementation Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fedora | 15 | May 24, 2011 | Early pioneer; integrates with dracut for initramfs and SELinux for security; upstream contributions heavy due to Red Hat involvement.[58][59] |

| openSUSE | 12.1 | November 4, 2011 | Replaces SysV init; uses zypper for package management and YaST for configuration; supports transactional updates in later variants.[60] |

| Arch Linux | Core transition in late 2012 | Rolling release | Minimal base install; mkinitcpio hooks enable systemd; user extensibility via pacman and AUR for custom units.[61][62] |

| RHEL | 7 | June 10, 2014 | Enterprise focus with SysV compatibility; firewalld and NetworkManager units standard; long-term support backports.[56] |

| Debian | 8 (Jessie) | April 26, 2015 | Post-vote adoption; supports multi-init via alternatives; integrates with policykit and elogind for session management.[63] |

| Ubuntu | 15.04 (Vivid Vervet) | April 23, 2015 | Full shift from Upstart; cloud-init and snapd units prominent; apport for crash reporting leverages journald.[64][65] |

Compatibility with Existing Software