Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

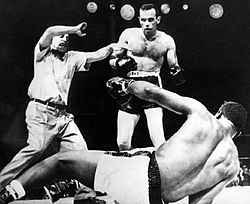

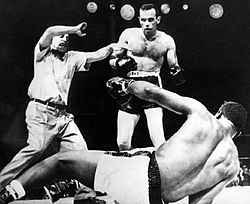

Knockout

View on Wikipedia

A knockout (abbreviated to KO or K.O.) is a fight-ending, winning criterion in several full-contact combat sports, such as boxing, kickboxing, Muay Thai, mixed martial arts, karate, some forms of taekwondo and other sports involving striking, as well as fighting-based video games. A full knockout is considered any legal strike or combination thereof that renders an opponent unable to continue fighting.

The term is often associated with a sudden traumatic loss of consciousness caused by a physical blow. Single powerful blows to the head (particularly the jawline and temple) can produce a cerebral concussion or a carotid sinus reflex with syncope and cause a sudden, dramatic KO. Body blows, particularly the liver punch, can cause progressive, debilitating pain that can also result in a KO.

In boxing and kickboxing, a knockout is usually awarded when one participant falls to the canvas and is unable to rise to their feet within a specified period of time, typically because of exhaustion, pain, disorientation, or unconsciousness. For example, if a boxer is knocked down and is unable to continue the fight within a ten-second count, they are counted as having been knocked out and their opponent is awarded the KO victory.

In mixed martial arts (MMA) competitions, no time count is given after a knockdown, as the sport allows submission grappling as well as ground and pound. If a fighter loses consciousness ("goes limp") as a result of legal strikes, it is declared a KO.[1] Even if the fighter loses consciousness for a brief moment and wakes up again to continue to fight, the fight may be stopped and a KO declared.[2] As many MMA fights can take place on the mat rather than standing, it is possible to score a KO via ground and pound, a common victory for grapplers.

In fighting games such as Street Fighter and Tekken, a player scores a knockout by fully depleting the opponent's health bar, with the victor being awarded the round. The player who wins the most rounds, either by scoring the most knockouts or by having more vitality remaining when time expires during each round, wins the match. In some fighting games like Soul Calibur as well as platform fighters like Super Smash Bros, the player can also score a KO when the opponent fall off the fighting area. This differs from combat sports in reality, where a knockout ends the match immediately. However, some fighting games aim for a more realistic experience, with titles like Fight Night adhering to the rules of professional boxing, although technically they are classified as sports games, and share many of the same features as NFL and NBA video games.

Technical knockout

[edit]

A technical knockout (TKO or T.K.O.), stoppage, or referee stopped contest (RSC) is declared when the referee decides during a round that a fighter cannot safely continue the match for any reason. Certain sanctioning bodies also allow the official attending physician at ringside to stop the fight as well. In amateur boxing, and in many regions professionally, including championship fights sanctioned by the World Boxing Association (WBA), a TKO is declared when a fighter is knocked down three times in one round (called an "automatic knockout" in WBA rules).[3] Furthermore, in amateur boxing, a boxer automatically wins by TKO if his opponent is knocked down four times in an entire match.[4][5]

In MMA bouts, the referee may declare a TKO if a fighter cannot intelligently defend themselves while being repeatedly struck.[1]

Double knockout

[edit]A double knockout, both in real-life combat sports and in fighting-based video games, occurs when both fighters trade blows and knock each other out simultaneously and are both unable to continue fighting.

In amateur boxing, a double knockout result is determined based on the round of competition. In all contests except the final, both fighters are declared to have lost the contest and are eliminated, since a boxer is suspended 30-540 days for a knockout under boxing regulations. In the final, where there must be a winner, the contest ends as if the bell sounded at the end of the final round, and the round is scored, with the winner determined by points. However, if both boxers are downed, both rise up, but one has reached the limit of knockdowns, the winning boxer is the one who has not reached the three/four knockdown limit.[5]

Physical characteristics

[edit]

Little is known as to what exactly causes one to be knocked unconscious, but many agree it is related to trauma to the brain stem. This usually happens when the head rotates sharply, often as a result of a strike. There are three general manifestations of such trauma:

- a typical knockout, which results in a sustained (three seconds or more) loss of consciousness (comparable to general anesthesia, in that the recipient emerges and has lost memory of the event).

- a "flash" knockout, when a very transient (less than three seconds) loss of consciousness occurs (in the context of a knock-down) and the recipient often maintains awareness and memory of the combat.

- a "stunning", a "dazing" or a fighter being "out on his feet", when basic consciousness is maintained (and the fighter never leaves his feet) despite a general loss of awareness and extreme distortions in proprioception, balance, visual fields, and auditory processing. Referees are taught specifically to watch for this state, as it cannot be improved by sheer willpower and usually means the fighter is already concussed and unable to safely defend themselves.

A basic principle of boxing and other combat sports is to defend against this vulnerability by keeping both hands raised about the face and the chin tucked in. This may still be ineffective if the opponent punches effectively to the solar plexus.

A fighter who becomes unconscious from a strike with sufficient knockout power is referred to as having been knocked out or KO'd (kay-ohd). Losing balance without losing consciousness is referred to as being knocked down ("down but not out"). Repeated blows to the head, regardless of whether they cause loss of consciousness, may in severe cases cause strokes or paralysis in the immediacy,[6] and over time have been linked to permanent neurodegenerative diseases such as chronic traumatic encephalopathy ("punch-drunk syndrome"). Because of this, many physicians advise against sports involving knockouts.[7]

Knockdown

[edit]

A knockdown occurs when a fighter touches the floor of the ring with any part of the body other than the feet following a hit, but is able to rise back up and continue fighting. The term is also used if the fighter is hanging on to the ropes, caught between the ropes, or is hanging over the ropes and is unable to fall to the floor and cannot protect himself. A knockdown triggers a count by the referee (normally to 10); if the fighter fails the count, then the fight is ended as a KO.[8]

A flash knockdown is a knockdown in which the fighter hits the canvas but is not noticeably hurt or affected.[8]

Boxing's 50 knockout club (professional boxers with 50 or more knockouts)

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2024) |

- Billy Bird 138

- Archie Moore 132

- Young Stribling 126

- Sam Langford 126

- Buck Smith 120

- Kid Azteca 114

- George Odwell 111

- Sugar Ray Robinson 109

- Clarence Reeves 108

- Peter Maher (boxer) 107

- Sandy Saddler 103

- Henry Armstrong 101

- Joe Gans 100

- Jimmy Wilde 98

- Len Wickwar 94

- Jorge Castro (boxer) 90

- Tiger Jack Fox 89

- Jock McAvoy 88

- Julio César Chávez 86

- Yori Boy Campas 83

- Chalky Wright 83

- Tommy Freeman 83

- Jose Luis Ramirez 82

- Charles Ledoux 81

- Ted Kid Lewis 80

- Fritzie Zivic 80

- Rubén Olivares 79

- George Godfrey 77

- George Chaney 76

- Torpedo Billy Murphy 76

- Ceferino Garcia 74

- Lee Savold 72

- Primo Carnera 72

- Benny Bass 72

- Rodolfo Gonzalez (boxer) 71

- Tommy Ryan 71

- Roberto Durán 70

- Benny Leonard 70

- Earnie Shavers 70

- Jesus Pimentel 68

- Fred Fulton 68

- George Foreman 68

- Joe Jeanette 68

- Lou Brouillard 67

- Tommy Gomez 67

- Pedro Carrasco 66

- Billy Petrolle 66

- Marcel Cerdan 66

- Jack Dillon 66

- Willie Pep 65

- Elmer Ray 64

- George Chuvalo 63

- Carlos Zárate Serna 63

- Frank Moody 63

- Martín Vargas 63

- Eduardo Lausse 62

- Alexis Argüello 62

- Jack Kid Berg 61

- Barbados Joe Walcott 61

- Larry Gains 61

- Adilson Rodrigues 61

- Mickey Walker (boxer) 60

- Freddie Steele 60

- Ike Williams 60

- Cleveland Williams 60

- Gregorio Peralta 60

- Tami Mauriello 60

- Max Baer (boxer) 59

- Young Peter Jackson 59

- Carlos Monzon 59

- Joe Knight (boxer) 59

- Ricardo Moreno 59

- Panama Al Brown 59

- Kid Pascualito 59[9]

- James Red Herring 58

- Eric Esch 58

- Tony Galento 57

- John Henry Lewis 57

- Pascual Perez 57

- Charley White 57

- Kid Williams 57

- Len Harvey 57

- Jose Luis Castillo 57

- Bob Fitzsimmons 57

- Tiger Flowers 56

- Georges Carpentier 56

- Pedro Montanez 56

- Irish Bob Murphy 56

- Charles Kid McCoy 55

- Dixie Kid 55

- Gorilla Jones 55

- Freddie Mills 55

- Manuel Ortiz 54

- Marcel Thil 54

- Solly Krieger 54

- Jose Napoles 54

- Bennie Briscoe 53

- Obie Walker 53

- Peter Kane 53

- Wladimir Klitschko 53

- Shannon Briggs 53

- Eugene Criqui 53

- Joe Louis 52

- Mike McTigue 52

- Philadelphia Jack O'Brien 52

- Lew Jenkins 52

- Marvin Hagler 52

- Rocky Graziano 52

- Ezzard Charles 52

- Arturo Godoy 52

- Kid Chocolate 51

- Packey McFarland 51

- Jimmy Slattery 51

- Abe Attell 51

- Miguel Angel Castellini 51

- Jorge Vaca 51

- Jorge Paez 51

- Marco Antonio Rubio 51

- Charley Burley 50

- Jose Legra 50

- Eder Jofre 50

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Rules and Regulations - Unified Rules and Other MMA Regulations". www.ufc.com. Archived from the original on 2016-04-16.

- ^ http://mixedmartialarts.com/mma-news/341856/Herb-Dean-The-fight-is-over-when-hes-unconscious[permanent dead link]

- ^ "WBA Rules as Amended at Directorate Meeting in Orlando, Florida - December 2022" (PDF). WBA Boxing. Retrieved 2024-02-04.

- ^ Sugar, Bert. Boxing[usurped]. www.owingsmillsboxingclub.com. URL last accessed March 4, 2006.

- ^ a b "World Boxing Competition Rules" (PDF). World Boxing. Retrieved 2024-12-02.

- ^ "Boxer gets record $22 million settlement from New York in brain injury case". mmafighting.com. 8 September 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-09-18.

- ^ Lieberman, Abraham (1 April 2005), Causing Parkinson: Boxing, Brain Injury, archived from the original on 15 May 2006, retrieved 24 June 2010

- ^ a b Boxing Terminology Archived 2012-06-25 at the Wayback Machine Ringside by Gus. URL last accessed June 17, 2008.

- ^ "BoxRec: Kid Pascualito". Archived from the original on 2023-09-09. Retrieved 2020-08-12.