Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Teda language.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Teda language

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

| Teda | |

|---|---|

| Tedaga | |

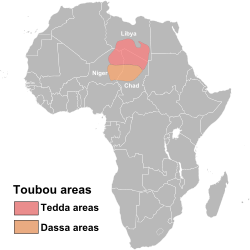

| Native to | Chad, Libya, Niger[1] |

| Region | BET, Kanem, Tibesti, Murzuq, Agadez |

| Ethnicity | Teda |

Native speakers | 130,000 (2020–2024)[1] |

| Latin | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | tuq |

| Glottolog | teda1241 |

| ELP | Tedaga |

| Linguasphere | 02-BAA-aa |

| |

The Teda language, also known as Tedaga, Todaga, Todga, or Tudaga is a Nilo-Saharan language spoken by the Teda, a northern subgroup of the Toubou people who inhabit southern Libya, northern Chad and eastern Niger. A small number also inhabit northeastern Nigeria.[1]

Along with the more populous southern dialect of Daza, the northern Teda dialect constitutes one of the two varieties of Tebu. However, Teda is also sometimes used for Tebu in general.

Phonology

[edit]Consonants

[edit]| Labial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | t | t͡ʃ | k | ||

| voiced | b | d | d͡ʒ | g | |||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | ç | h | |

| voiced | v | z | ɣ | ||||

| Approximant | l | j | w | ||||

Vowels

[edit]| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | ʉ | u |

| Near-close | ɪ | ʊ | |

| Close-mid | e | o | |

| Mid | ə | ||

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɔ | |

| Open | a |

Alphabet

[edit]

| A a | Ã ã | B b | Č č | D d | E e | Ê ê | G g | H h | I i | Î î | Ĩ ĩ | K k | L l | M m | N n | Ñ ñ |

| NJ nj | Ŋ ŋ | O o | Ô ô | P p | R r | S s | Š š | T t | U u | Û û | Ũ ũ | W w | Y y | Z z | Y y | Z z |

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Teda at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

- ^ a b Chanard, Christian; Hartell, Rhonda L. (2019). Moran, Steven; McCloy, Daniel (eds.). "Tedaga sound inventory (AA)". PHOIBLE. 2.0. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. Retrieved 2024-09-25.

- Barth, Heinrich (1854). "Schreiben an Prof. Lepsius über die Beziehung der Kanori- und Teda-Sprachen". Zeitschrift für Erdkunde. 2: 372–374, 384–387.

- Chonai, Hassan (1998). Gruppa teda-kanuri (centraľnosaxarskaja sem'ja jazykov) i ee genetičeskie vzaimootnošenija (ėtimologičeskij i fonologičeskij aspekt) (PhD thesis). Moskva: Rossijskij gosudarstvennyj gumanitarnyj universitet.

- Haggar, Inouss; Walters, K. (2005). Lexique tubu (dazaga)-français et glossaire français-tubu. Niamey: SIL Niger.

- Jourdan, P. (1935). Notes grammaticales et vocabulaire de la langue Daza. London: Kegan, Paul, Trench & Trubner.

- Le Cœur, C. (1950). Dictionnaire ethnographique téda, précédé d'un lexique français-téda. Dakar: IFAN.

- Le Cœur, C.; Le Cœur, M. (1956). "Grammaire et textes teda-daza". Mémoires de l'IFAN. 46. Dakar: Institut Français d’Afrique Noire.

- Lukas, Johannes (1951–1952). "Umrisse einer ostsaharanischen Sprachgruppe". Afrika und Übersee. 36: 3–7.

- Lukas, Johannes (1953). Die Sprache der Tubu in der zentralen Sahara. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

- "Audio records of Daza-Teda languages". 1946.

Teda language

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

Overview

Classification

The Teda language, also known as Tedaga, belongs to the Nilo-Saharan phylum, specifically the Saharan branch and the Tebu subgroup.[1] This classification positions Teda within a small but well-established family of Saharan languages characterized by shared areal features in the central Sahara.[4] Teda forms part of the Tebu language group alongside Daza, its closest relative, where Teda represents the northern dialect continuum spoken primarily by the Teda subgroup of the Toubou people. The two languages exhibit high mutual intelligibility, with phonological similarities such as vowel harmony patterns. The ISO 639-3 code for Teda is tuq, and its Glottolog identifier is teda1241.[4] The broader Nilo-Saharan phylum's genetic unity, first proposed by Greenberg in 1963, remains debated among linguists, though supporting evidence includes shared basic lexicon (e.g., pronouns and body part terms) and morphological elements like verbal extensions and case marking.[5] Within Saharan, Teda (Central subgroup via Tebu) is distinct from Western Saharan languages like Kanuri and Eastern Saharan ones like Zaghawa, differing in subgroup-specific innovations in syntax and nominal morphology.[6]Geographic distribution

The Teda language is primarily spoken across the Sahara Desert in northern Chad, particularly in the Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti region, including the Tibesti Mountains and areas around Bardai. Speakers are also present in southern Libya's Murzuq District within the Fezzan region, northern Niger's Agadez Region encompassing locales such as Bilma, Seguedine, and the Termit Massif, and to a lesser extent in northeastern Nigeria near the Chad border.[7][8][9] As of 2024, the language has approximately 130,000 native speakers worldwide, primarily in Chad and Niger (over 100,000 combined), with smaller populations (under 10,000 each) in Libya and Nigeria.[1][10] Teda is the primary language of the Teda subgroup within the broader Toubou (or Tubu) ethnic group, comprising both nomadic pastoralists who herd camels and goats across desert routes and sedentary communities involved in oasis agriculture, date palm cultivation, and caravan trade.[2][11] The nomadic traditions and transborder migrations of Teda speakers, facilitated by the fluid Saharan landscape, contribute to dialectal variations, with influences from adjacent interactions shaping local forms of the language.[8][2] Overall, Teda maintains stable vitality in its indigenous heartlands, though smaller diaspora populations in peripheral areas like Nigeria and Libya face risks of endangerment due to assimilation pressures.[1] Teda speakers coexist with Daza communities in overlapping Saharan zones, where the related Daza language is also prevalent.[4]Phonology

Consonants

The Teda language, part of the Teda-Daza dialect continuum within the Saharan branch of Nilo-Saharan, features a consonant inventory of 20 phonemes.[12] These include stops, fricatives, nasals, affricates, liquids, and glides, articulated across bilabial, labiodental, alveolar, alveopalatal, palatal, velar, and glottal places.[12] There is no phonemic /p/; instead, appears as an allophone of /b/.[12] The following table presents the consonant phonemes organized by place and manner of articulation, using IPA symbols:| Bilabial | Labiodental | Alveolar | Alveopalatal | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stops | b | t d | k ɡ | ||||

| Affricates | tʃ dʒ | ||||||

| Fricatives | f | s z | ʃ | h | |||

| Nasals | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | |||

| Liquids | l ɾ | ||||||

| Glides | w | j |

Vowels

The Teda-Daza language, also known as Teda or Tedaga in its eastern varieties, possesses a vowel inventory of nine phonemes organized into harmonic sets based on the advanced tongue root ([+ATR]) feature. These include four [+ATR] vowels (/i/, /u/, /e/, /o/) and five [-ATR] vowels (/ɪ/, /ʊ/, /ɛ/, /ɔ/, /a/), with the low vowel /a/ being inherently [-ATR] and transparent to harmony processes.[12] Vowel qualities are symmetrically distributed across height and backness, as shown in the following chart:| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i, ɪ | u, ʊ | |

| Mid | e, ɛ | o, ɔ | |

| Low | a |