Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Irish language

View on Wikipedia

| Irish | |

|---|---|

| Irish Gaelic | |

| Standard Irish: Gaeilge | |

| Pronunciation | Connacht Irish: [ˈɡeːlʲɟə] Munster Irish: [ˈɡeːl̪ˠən̠ʲ] Ulster Irish: [ˈɡeːlʲəc] |

| Native to | Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland |

| Region | Ireland |

| Ethnicity | Irish people |

Native speakers | L1: unknown People aged 3+ stating they could speak Irish "very well": (ROI, 2022) 195,029 Daily users outside education system: (ROI, 2022) 71,968 (NI, 2021) 43,557 L2: unknown People aged 3+ stating they could speak Irish: (ROI, 2022) 1,873,997 (NI, 2021) 228,600 |

Early forms | |

Standard forms | An Caighdeán Oifigiúil (written only) |

| Dialects | |

| Latin (Irish alphabet) Ogham (historically) Irish Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ga |

| ISO 639-2 | gle |

| ISO 639-3 | gle |

| Glottolog | iris1253 |

| ELP | Irish |

| Linguasphere | 50-AAA |

Proportion of respondents who said they could speak Irish in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland censuses of 2011 | |

Irish is classified as Definitely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger.[3] | |

Irish (Standard Irish: Gaeilge), also known as Irish Gaelic or simply Gaelic (/ˈɡeɪlɪk/ ⓘ GAY-lik),[b] is a Celtic language of the Indo-European language family that belongs to the Goidelic languages and further to Insular Celtic, and is indigenous to the island of Ireland.[10] It was the majority of the population's first language until the 19th century, when English gradually became dominant, particularly in the last decades of the century, in what is sometimes characterised as a result of linguistic imperialism.

Today, Irish is still commonly spoken as a first language in Ireland's Gaeltacht regions, in which 2% of Ireland's population lived in 2022.[11]

The total number of people (aged 3 and over) in Ireland who declared they could speak Irish in April 2022 was 1,873,997, representing 40% of respondents, but of these, 472,887 said they never spoke it and a further 551,993 said they only spoke it within the education system.[11] Linguistic analyses of Irish speakers are therefore based primarily on the number of daily users in Ireland outside the education system, which in 2022 was 20,261 in the Gaeltacht and 51,707 outside it, totalling 71,968.[11] In the 2021 census of Northern Ireland, 43,557 individuals stated they spoke Irish on a daily basis, 26,286 spoke it on a weekly basis, 47,153 spoke it less often than weekly, and 9,758 said they could speak Irish, but never spoke it.[12] From 2006 to 2008, over 22,000 Irish Americans reported speaking Irish as their first language at home, with several times that number claiming "some knowledge" of the language.[13]

For most of recorded Irish history, Irish was the dominant language of the Irish people, who took it with them to other regions, such as Scotland and the Isle of Man, where Middle Irish gave rise to Scottish Gaelic and Manx. It was also, for a period, spoken widely across Canada, with an estimated 200,000–250,000 daily Canadian speakers of Irish in 1890.[14] On the island of Newfoundland, a unique dialect of Irish developed before falling out of use in the early 20th century.

With a writing system, Ogham, dating back to at least the 4th century AD, which was gradually replaced by Latin script since the 5th century AD, Irish has one of the oldest vernacular literatures in Western Europe. On the island, the language has three major dialects: Connacht, Munster, and Ulster Irish. All three have distinctions in their speech and orthography. There is also An Caighdeán Oifigiúil, a standardised written form devised by a parliamentary commission in the 1950s. The traditional Irish alphabet, a variant of the Latin alphabet with 18 letters, has been succeeded by the standard Latin alphabet (albeit with 7–8 letters used primarily in loanwords).

Irish has constitutional status as the national and first official language of the Republic of Ireland, and is also an official language of Northern Ireland and among the official languages of the European Union. The public body Foras na Gaeilge is responsible for the promotion of the language throughout the island. Irish has no regulatory body but An Caighdeán Oifigiúil, the standard written form, is guided by a parliamentary service and new vocabulary by a voluntary committee with university input.

Name of the language

[edit]In Irish

[edit]In An Caighdeán Oifigiúil ("The Official [Written] Standard") the name of the language is Gaeilge, from the south Connacht form, spelled Gaedhilge prior the spelling reform of 1948, in which the silent ⟨dh⟩ was removed. Gaedhilge was originally the genitive of Gaedhealg, the form used in Classical Gaelic.[15] Older spellings include Gaoidhealg [ˈɡeːʝəlˠəɡ] in Classical Gaelic and Goídelc [ˈɡoiðʲelɡ] in Old Irish. Goidelic, used to refer to the language family, is derived from the Old Irish term.

Endonyms of the language in the various modern Irish dialects include: Gaeilge [ˈɡeːlʲɟə] in Galway, Gaeilg/Gaeilic/Gaeilig [ˈɡeːlʲəc][16] in Mayo and Ulster, Gaelainn/Gaoluinn [ˈɡeːl̪ˠən̠ʲ] in West Cork and Kerry (Munster), as well as Gaedhealaing in mid- and eastern Munster (Waterford and parts of Cork and Kerry), to reflect local pronunciation.[17][18]

Gaeilge as a term can apply to the very closely related languages Scottish Gaelic and Manx as well as Irish. When context requires it, these three are distinguished as Gaeilge na hAlban, Gaeilge Mhanann and Gaeilge na hÉireann respectively.[19]

In English

[edit]In English (including Hiberno-English), the language is usually referred to as Irish, as well as Gaelic and Irish Gaelic.[20][21] The term Irish Gaelic may be seen when English speakers discuss the relationship between the three Goidelic languages (Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Manx).[22] Gaelic is a collective term for the Goidelic languages,[9][23][4][8][24] and when the context is clear it may be used without qualification to refer to each language individually. When the context is specific but unclear, the term may be qualified, as Irish Gaelic, Scottish Gaelic or Manx Gaelic. Historically the name "Erse" (/ɜːrs/ URS) was also sometimes used in Scots and then in English to refer to Irish;[25] as well as Scottish Gaelic.

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2024) |

Primitive Irish

[edit]Written Irish is first attested in Ogham inscriptions from the 4th century AD,[26] a stage of the language known as Primitive Irish. These writings have been found throughout Ireland and the west coast of Great Britain.

Old Irish

[edit]Primitive Irish underwent a change into Old Irish through the 5th century. Old Irish, dating from the 6th century, used the Latin alphabet and is attested primarily in marginalia to Latin manuscripts. During this time, the Irish language absorbed some Latin words, some via Old Welsh, including ecclesiastical terms: examples are easpag (bishop) from episcopus, and Domhnach (Sunday, from dominica).

Middle Irish

[edit]By the 10th century, Old Irish had evolved into Middle Irish, which was spoken throughout Ireland, the Isle of Man and parts of Scotland. It is the language of a large corpus of literature, including the Ulster Cycle. From the 12th century, Middle Irish began to evolve into modern Irish in Ireland, Scottish Gaelic in Scotland, and Manx on the Isle of Man.

Early Modern Irish

[edit]Early Modern Irish, dating from the 13th century, was the basis of the literary language of both Ireland and Gaelic-speaking Scotland.

Modern Irish

[edit]Modern Irish, sometimes called Late Modern Irish, as attested in the work of such writers as Geoffrey Keating, is said to date from the 17th century, and was the medium of popular literature from that time on.[27][28]

Decline

[edit]From the 18th century on, the language lost ground in the east of the country. The reasons behind this shift were complex but came down to a number of factors:

- Discouragement of its use by the Anglo-Irish administration.

- The Catholic Church's support of English over Irish.

- The spread of bilingualism from the 1750s onwards.[29]

The change was characterised by diglossia (two languages being used by the same community in different social and economic situations) and transitional bilingualism (monoglot Irish-speaking grandparents with bilingual children and monoglot English-speaking grandchildren). By the mid-18th century, English was becoming a language of the Catholic middle class (which descended from both the Hiberno-Norman and old Gaelic nobilities of Ireland), the Catholic Church and public intellectuals, especially in the east of the country. Increasingly, as the value of English became apparent, parents sanctioned the prohibition of Irish in schools.[30] Increasing interest in emigrating to the United States and Canada was also a driver, as fluency in English allowed the new immigrants to get jobs in areas other than farming. An estimated one quarter to one third of US immigrants during the Great Famine were Irish speakers.[31]

Irish was not marginal to Ireland's modernisation in the 19th century, as is often assumed. In the first half of the century there were still around three million people for whom Irish was the primary language, and their numbers alone made them a cultural and social force. Irish speakers often insisted on using the language in law courts (even when they knew English), and Irish was also common in commercial transactions. The language was heavily implicated in the "devotional revolution" which marked the standardisation of Catholic religious practice and was also widely used in a political context. Down to the time of the Great Famine and even afterwards, the language was in use by all classes, Irish being an urban as well as a rural language.[32]

This linguistic dynamism was reflected in the efforts of certain public intellectuals to counter the decline of the language. At the end of the 19th century, they launched the Gaelic revival in an attempt to encourage the learning and use of Irish, although few adult learners mastered the language.[33] The vehicle of the revival was the Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge), and particular emphasis was placed on the folk tradition, which in Irish is particularly rich. Efforts were also made to develop journalism and a modern literature.

Although it has been noted that the Catholic Church played a role in the decline of the Irish language before the Gaelic Revival, the Protestant Church of Ireland also made only minor efforts to encourage use of Irish in a religious context. An Irish translation of the Old Testament by Leinsterman Muircheartach Ó Cíonga, commissioned by Bishop Bedell, was published after 1685 along with a translation of the New Testament. Otherwise, Anglicisation was seen as synonymous with 'civilising' the native Irish. Currently, modern day Irish speakers in the church are pushing for language revival.[34]

It has been estimated that there were around 800,000 monoglot Irish speakers in 1800, which dropped to 320,000 by the end of the famine, and under 17,000 by 1911.[35]

The Gaelic Revival

[edit]The Gaelic revival (Irish: Athbheochan na Gaeilge) was the late-nineteenth-century national revival of interest in the Irish language[36] and Irish Gaelic culture (including folklore, mythology, sports, music, arts, etc.).

The Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge) was established in 1893 by Eoin MacNeill and other enthusiasts of Gaelic language and culture. Its first president was Douglas Hyde. The objective of the league was to encourage the use of Irish in everyday life in order to counter the ongoing anglicisation of the country. It organised weekly gatherings to discuss Irish culture, hosted conversation meetings, edited and periodically published a newspaper named An Claidheamh Soluis, and successfully campaigned to have Irish included in the school curriculum. The league grew quickly, having more than 48 branches within four years of its foundation and 400 within 10. It had fraught relationships with other cultural movements of the time, such as the Pan-Celtic movement and the Irish Literary Revival.

Important writers of the Gaelic revival include Peadar Ua Laoghaire, Patrick Pearse (Pádraig Mac Piarais) and Pádraic Ó Conaire.

Status and policy

[edit]Ireland

[edit]Irish is recognised by the Constitution of Ireland as the national and first official language of the Republic of Ireland (English being the other official language). Despite this, almost all government business and legislative debate is conducted in English.[37]

In 1938, the founder of Conradh na Gaeilge (Gaelic League), Douglas Hyde, was inaugurated as the first President of Ireland. The record of his delivering his inaugural Declaration of Office in Roscommon Irish is one of only a few recordings of that dialect.[38][39][40][41]

In the 2016 census, 10.5% of respondents stated that they spoke Irish, either daily or weekly, while over 70,000 people (4.2%) speak it as a habitual daily means of communication.[42]

From the foundation of the Irish Free State in 1922 (see History of the Republic of Ireland), new appointees to the Civil Service of the Republic of Ireland, including postal workers, tax collectors, agricultural inspectors, Garda Síochána (police), etc., were required to have some proficiency in Irish. By law, a Garda who was addressed in Irish had to respond in Irish as well.[43]

In 1974, in part through the actions of protest organisations like the Language Freedom Movement, the requirement for entrance to the public service was changed to proficiency in just one official language.

Nevertheless, Irish remains a required subject of study in all schools in the Republic of Ireland that receive public money (see Education in the Republic of Ireland). Teachers in primary schools must also pass a compulsory examination called Scrúdú Cáilíochta sa Ghaeilge. As of 2005, Garda Síochána recruits need a pass in Leaving Certificate Irish or English, and receive lessons in Irish during their two years of training. Official documents of the Irish government must be published in both Irish and English or Irish alone (in accordance with the Official Languages Act 2003, enforced by An Coimisinéir Teanga, the Irish language ombudsman).

The National University of Ireland requires all students wishing to embark on a degree course in the NUI federal system to pass the subject of Irish in the Leaving Certificate or GCE/GCSE examinations.[44] Exemptions are made from this requirement for students who were born or completed primary education outside of Ireland, and students diagnosed with dyslexia.

The University of Galway is required to appoint people who are competent in the Irish language, as long as they are also competent in all other aspects of the vacancy to which they are appointed. This requirement is laid down by the University College Galway Act 1929 (Section 3).[45] In 2016, the university faced controversy when it announced the planned appointment of a president who did not speak Irish. Misneach[further explanation needed] staged protests against this decision. The following year the university announced that Ciarán Ó hÓgartaigh, a fluent Irish speaker, would be its 13th president. He assumed office in January 2018; in June 2024, he announced he would be stepping down as president at the beginning of the following academic year.[46]

For a number of years there has been vigorous debate in political, academic and other circles about the failure of most students in English-medium schools to achieve competence in Irish, even after fourteen years of teaching as one of the three main subjects.[47][48][49] The concomitant decline in the number of traditional native speakers has also been a cause of great concern.[50][51][52][53]

In 2007, filmmaker Manchán Magan found few Irish speakers in Dublin, and faced incredulity when trying to get by speaking only Irish in Dublin. He was unable to accomplish some everyday tasks, as portrayed in his documentary No Béarla.[54]

There is, however, a growing body of Irish speakers in urban areas, particularly in Dublin. Many have been educated in schools in which Irish is the language of instruction. Such schools are known as Gaelscoileanna at primary level. These Irish-medium schools report some better outcomes for students than English-medium schools.[55] In 2009, a paper suggested that within a generation, non-Gaeltacht habitual users of Irish might typically be members of an urban, middle class, and highly educated minority.[56]

Article 25.4 of the Constitution of Ireland requires that an "official translation" of any law in one official language be provided immediately in the other official language, if not already passed in both official languages.[1] Notwithstanding this, legislation is frequently only available in English.

In November 2016, RTÉ reported that over 2.3 million people worldwide were learning Irish through the Duolingo app.[57] In 2017, Michael D. Higgins, president of Ireland, honoured several volunteer translators for developing the Irish edition, and said the push for Irish language rights remains an "unfinished project".[58]

Gaeltacht

[edit]

There are rural areas of Ireland where Irish is still spoken daily to some extent as a first language. These regions are known individually and collectively as the Gaeltacht (plural Gaeltachtaí). While the fluent Irish speakers of these areas, whose numbers have been estimated at 20–30,000,[59] are a minority of the total number of fluent Irish speakers, they represent a higher concentration of Irish speakers than other parts of the country and it is only in Gaeltacht areas that Irish continues to be spoken as a community vernacular to some extent.

According to data compiled by the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media, only 1/4 of households in Gaeltacht areas are fluent in Irish. The author of a detailed analysis of the survey, Donncha Ó hÉallaithe of the Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology, described the Irish language policy followed by Irish governments as a "complete and absolute disaster". The Irish Times, referring to his analysis published in the Irish language newspaper Foinse, quoted him as follows: "It is an absolute indictment of successive Irish Governments that at the foundation of the Irish State there were 250,000 fluent Irish speakers living in Irish-speaking or semi Irish-speaking areas, but the number now is between 20,000 and 30,000."[59]

In the 1920s, when the Irish Free State was founded, Irish was still a vernacular in some western coastal areas.[60] In the 1930s, areas where more than 25% of the population spoke Irish were classified as Gaeltacht. Today, the strongest Gaeltacht areas, numerically and socially, are those of South Connemara, the west of the Dingle Peninsula, and northwest Donegal, where many residents still use Irish as their primary language. These areas are often referred to as the Fíor-Ghaeltacht (true Gaeltacht), a term originally officially applied to areas where over 50% of the population spoke Irish.

There are Gaeltacht regions in the following counties:[61][62]

- County Galway (Contae na Gaillimhe)

- Connemara (Conamara)

- Aran Islands (Oileáin Árann)

- Carraroe (An Cheathrú Rua)

- Spiddal (An Spidéal)

- County Mayo (Contae Mhaigh Eo)

- County Donegal (Contae Dhún na nGall)

- County Kerry (Contae Chiarraí)

- Dingle Peninsula (Corca Dhuibhne)

- Iveragh Peninsula (Uibh Rathach)

- County Cork (Contae Chorcaí)

- County Waterford (Contae Phort Láirge)

- County Meath (Contae na Mí)

Gweedore (Gaoth Dobhair), County Donegal, is the largest Gaeltacht parish in Ireland. Irish language summer colleges in the Gaeltacht are attended by tens of thousands of teenagers annually. Students live with Gaeltacht families, attend classes, participate in sports, go to céilithe and are obliged to speak Irish. All aspects of Irish culture and tradition are encouraged.

Policy

[edit]Official Languages Act 2003

[edit]

The Act was passed 14 July 2003 with the main purpose of improving the number and quality of public services delivered in Irish by the government and other public bodies.[63] Compliance with the Act is monitored by An Coimisinéir Teanga (The Language Commissioner) which was established in 2004[64] and any complaints or concerns pertaining to the act are brought to them.[63] The act details different aspects of the use of Irish in official documentation and communication. Included in these sections are subjects such as Irish language use in courts, official publications, and place names.[65] The act was amended in December 2019 in order to strengthen the legislation.[66] All changes made took into account data collected from online surveys and written submissions.[67]

Official Languages Scheme 2019–2022

[edit]The Official Languages Scheme was enacted 1 July 2019 and is an 18-page document that adheres to the guidelines of the Official Languages Act 2003.[68] The purpose of the scheme is to provide services through the media of Irish and/or English. According to the Department of the Taoiseach, it is meant to "develop a sustainable economy and a successful society, to pursue Ireland's interests abroad, to implement the Government's Programme and to build a better future for Ireland and all her citizens".[69]

20-Year Strategy for the Irish Language 2010–2030

[edit]In December 2010, the government of Ireland launched the 20-Year Strategy for the Irish Language 2010–2030 (Straitéis 20 Bliain don Ghaeilge 2010–2030).[70][71][72] The 30-page policy and planning document, which is due to run until 2030, is intended to target language vitality and revitalization of the Irish language.[73] The policy is divided into four phases and is intended to improve nine main areas:

- Education

- The Gaeltacht

- Family Transmission of the Language – Early Intervention

- Administration, Services and Community

- Media and Technology

- Dictionaries

- Legislation and Status

- Economic Life

- Cross-cutting Initiatives[73]

In June 2018, Joe McHugh, Minister of State at the Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, launched the first cross-governmental Action Plan for the 20-Year Strategy for the strategy, which was to operate between 2018 and 2022.[74]

While the strategy aims to increase the number of daily Irish speakers in Ireland from 83,000 to 250,000 by 2030, the number of such speakers had fallen to 71,968 by 2022.[11]

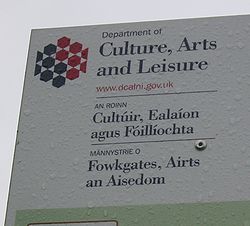

Northern Ireland

[edit]

Before the partition of Ireland in 1921, Irish was recognised as a school subject and as "Celtic" in some third level institutions. Between 1921 and 1972, government in Northern Ireland was devolved. During those years, the political party holding power in the Stormont Parliament, the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), was hostile to the language as it was almost exclusively used by nationalists.[75] In broadcasting, reporting minority cultural issues was prohibited and Irish was excluded from radio and television for almost the first fifty years of the devolved government.[76]

After the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, Irish in Northern Ireland gradually gained a degree of formal recognition from the United Kingdom.[77] In 2003, the British government ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages with respect to the use of Irish in Northern Ireland. In the 2006 St Andrews Agreement, the British government pledged to enact legislation to promote the language[78] and in 2022 it approved legislation to recognise Irish as an official language alongside English. The bill received royal assent on 6 December 2022.[2]

The status of Irish has often been used as a bargaining chip during government formation in Northern Ireland, prompting protests from organisations and groups such as An Dream Dearg.[79]

European Parliament

[edit]Irish became an official language of the EU on 1 January 2007, meaning that MEPs fluent in Irish can now speak the language in the European Parliament and at committees, though in the case of the latter they have to give prior notice to a simultaneous interpreter to ensure that what they say can be interpreted into other languages.

Although Irish was an official EU language, only co-decision regulations were available until 2022, due to a five-year derogation requested by the Irish government when negotiating the language's new official status. The Irish government had committed itself to train the necessary number of translators and interpreters and to bear the related costs.[80] When the derogation ended on 1 January 2022, Irish became a fully recognised EU language for the first time.[81] Before Irish became an official language, it was afforded the status of treaty language and only the highest-level documents of the EU were made available in Irish.

Outside Ireland

[edit]

The Irish language was carried abroad in the modern period by a vast diaspora, chiefly to Great Britain and North America, but also to Australia, New Zealand and Argentina.

The first large movements began in the 17th century, largely as a result of the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, which saw many Irish sent to the West Indies. Irish emigration to the United States was well established by the 18th century, and was reinforced in the 1840s by thousands fleeing from the Famine. This flight also affected Britain. Up until that time most emigrants spoke Irish as their first language, though English was establishing itself as the primary language. Irish speakers had first arrived in Australia in the late 18th century as convicts and soldiers, and many Irish-speaking settlers followed, particularly in the 1860s. New Zealand also received some of this influx. Argentina was the only non-English-speaking country to receive large numbers of Irish emigrants, and there were few Irish speakers among them.

Relatively few of the emigrants were literate in Irish, but manuscripts in the language were brought to both Australia and the United States, and it was in the United States that the first newspaper to make significant use of Irish was established: An Gaodhal. In Australia, too, the language found its way into print. The Gaelic revival, which started in Ireland in the 1890s, found a response abroad, with branches of Conradh na Gaeilge being established in all the countries to which Irish speakers had emigrated.

The decline of Irish in Ireland and a slowing of emigration helped to ensure a decline in the language abroad, along with natural attrition in the host countries. Despite this, small groups of enthusiasts continued to learn and cultivate Irish in diaspora countries and elsewhere, a trend which strengthened in the second half of the 20th century. Today the language is taught at tertiary level in North America, Australia and Europe, and Irish speakers outside Ireland contribute to journalism and literature in the language. There are significant Irish-speaking networks in the United States and Canada;[82] figures released for the period 2006–2008 show that 22,279 Irish Americans claimed to speak Irish at home.[13]

The Irish language is also one of the languages of the Celtic League, a non-governmental organisation that promotes self-determination, Celtic identity and culture in Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Brittany, Cornwall and the Isle of Man, known collectively as the Celtic nations.

Irish was spoken as a community language until the early 20th century on the island of Newfoundland, in a form known as Newfoundland Irish.[83] Certain Irish vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation features are still used in modern Newfoundland English.[84]

Usage

[edit]The Irish government collects data on the Irish language in the Republic of Ireland via census. As of the 2022 census, 1,873,997 respondents over the age of 3 indicated that they were able to speak Irish (an increase of 6% from the 2016 number of 1,761,420), accounting for 40% of the population aged 3 years and over who completed the question. Of the state's population over age 3, 13% said that they spoke Irish daily, and 4% spoke it daily outside the education system.

Of all Irish speakers who answered the 2022 census, 10% reported speaking it 'very well', 32% spoke it 'well' and 55% indicated they did not speak it well. There was a clear age factor: 63% of Irish speakers between the ages of 15 and 19 reported speaking it 'well' or 'very well', as opposed to only 27% of those between ages 50 to 54[85].

Compiling all-island data is more challenging due to differences in how the Northern Irish census is conducted. In 2021, 228,617 of respondents over the age of 3 indicated that they had some ability in Irish, accounting for 12.45% of the Northern Ireland's population of 1,836,612. Combining this figure with that of the Republic's census indicates that 30% of the island's population has some command over the language. The Northern Irish figure includes some 90,801 respondents categorised as 'Understands but does not read, write or speak Irish' and as such these respondents may possess a level of Irish which is below any of those in the Republic's census.[86].

Daily Irish speakers in Gaeltacht areas between 2011 and 2022

[edit]| Gaeltacht Area | 2011 | 2016 | 2022 | Change 2011–2022 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | ||||||||

| County Cork | 982 | 872 | 847 | ||||||

| County Donegal | 7,047 | 5,929 | 5,753 | ||||||

| Galway City | 636 | 646 | 646 | ||||||

| County Galway | 10,085 | 9,445 | 9,373 | ||||||

| County Kerry | 2,501 | 2,049 | 2,131 | ||||||

| County Mayo | 1,172 | 895 | 727 | ||||||

| County Meath | 314 | 283 | 276 | ||||||

| County Waterford | 438 | 467 | 508 | ||||||

| All Gaeltacht Areas | 23,175 | 20,586 | 20,261 | ||||||

In 1996, the three electoral divisions in the State where Irish had the most daily speakers were An Turloch (91%+), Scainimh (89%+), Min an Chladaigh (88%+).[89]

Technology

[edit]Social media has provided new tools for promoting the Irish language. Influencers on platforms like Instagram and TikTok,[90] such as Aisling O'Neill and Irish Language Learner, share lessons, challenges, and everyday phrases in Irish as a way to engage their followers. This creative content can help to increase awareness and encourage younger audiences to embrace their cultural heritage.[citation needed]

On YouTube, channels such as Briathra - The Irish Language and TG Lurgan offer instructional videos ranging from pronunciation guides to grammar explanations. TG Lurgan[91] is known for transforming popular songs into Irish versions, promoting the language and cultural pride through music.

Dialects

[edit]Irish is represented by several traditional dialects and by various varieties of "urban" Irish. The latter have acquired lives of their own and a growing number of native speakers. Differences between the dialects make themselves felt in stress, intonation, vocabulary and structural features.

Roughly speaking, the three major dialect areas which survive coincide roughly with the provinces of Connacht (Cúige Chonnacht), Munster (Cúige Mumhan) and Ulster (Cúige Uladh). Records of some dialects of Leinster (Cúige Laighean) were made by the Irish Folklore Commission and others.[92] Newfoundland, in eastern Canada, had a form of Irish derived from the Munster Irish of the later 18th century (see Newfoundland Irish).

Connacht

[edit]Historically, Connacht Irish represents the westernmost remnant of a dialect area which once stretched across from the centre of Ireland. The strongest dialect of Connacht Irish is to be found in Connemara and the Aran Islands. Much closer to the larger Connacht Gaeltacht is the dialect spoken in the smaller region on the border between Galway (Gaillimh) and Mayo (Maigh Eo). There are a number of differences between the popular South Connemara form of Irish, the Mid-Connacht/Joyce Country form (on the border between Mayo and Galway) and the Achill and Erris forms in the northwest of the province.[citation needed]

Features in Connacht Irish differing from the official written standard include a preference for verbal nouns ending in -achan, e.g. lagachan instead of lagú, "weakening". The non-standard pronunciation of Cois Fharraige with lengthened vowels and heavily reduced endings gives it a distinct sound. Distinguishing features of Connacht and Ulster dialect include the pronunciation of word-final /w/ as [w], rather than as [vˠ] in Munster. For example, sliabh ("mountain") is [ʃlʲiəw] in Connacht and Ulster as opposed to [ʃlʲiəβ] in the south. In addition Connacht and Ulster speakers tend to include the "we" pronoun rather than use the standard compound form used in Munster, e.g. bhí muid is used for "we were" instead of bhíomar.[citation needed]

As in Munster Irish, some short vowels are lengthened and others diphthongised before ⟨ll, m, nn, rr, rd⟩, in monosyllabic words and in the stressed syllable of multisyllabic words where the syllable is followed by a consonant. This can be seen in ceann [cɑːn̪ˠ] "head", cam [kɑːmˠ] "crooked", gearr [ɟɑːɾˠ] "short", ord [ouɾˠd̪ˠ] "sledgehammer", gall [gɑːl̪ˠ] "foreigner, non-Gael", iontas [ˈiːn̪ˠt̪ˠəsˠ] "a wonder, a marvel", etc. The form ⟨(a)ibh⟩, when occurring at the end of words like agaibh, tends to be pronounced as [iː].[citation needed]

In South Connemara, for example, there is a tendency to replace word-final /vʲ/ with /bʲ/, in word such as sibh, libh and dóibh (pronounced respectively as "shiv", "liv" and "dófa" in the other areas). This placing of the B-sound is also present at the end of words ending in vowels, such as acu ([ˈakəbˠ]) and 'leo ([lʲoːbˠ]). There is also a tendency to omit /g/ in agam, agat and againn, a characteristic also of other Connacht dialects. All these pronunciations are distinctively regional.[citation needed]

The pronunciation prevalent in the Joyce Country (the area around Lough Corrib and Lough Mask) is quite similar to that of South Connemara, with a similar approach to the words agam, agat and againn and a similar approach to pronunciation of vowels and consonants but there are noticeable differences in vocabulary, with certain words such as doiligh (difficult) and foscailte being preferred to the more usual deacair and oscailte. Another interesting aspect of this sub-dialect is that almost all vowels at the end of words tend to be pronounced as [iː]: eile (other), cosa (feet) and déanta (done) tend to be pronounced as eilí, cosaí and déantaí respectively.[citation needed]

The northern Mayo dialect of Erris (Iorras) and Achill (Acaill) is in grammar and morphology essentially a Connacht dialect but shows some similarities to Ulster Irish due to large-scale immigration of dispossessed people following the Plantation of Ulster. For example, words ending -⟨bh, mh⟩ have a much softer sound, with a tendency to terminate words such as leo and dóibh with ⟨f⟩, giving leofa and dófa respectively. In addition to a vocabulary typical of other area of Connacht, one also finds Ulster words like amharc (meaning "to look"), nimhneach (painful or sore), druid (close), mothaigh (hear), doiligh (difficult), úr (new), and tig le (to be able to – i.e. a form similar to féidir).[citation needed]

Irish President Douglas Hyde was possibly one of the last speakers of the Roscommon dialect of Irish.[39][citation needed]

Munster

[edit]Munster Irish is the dialect spoken in the Gaeltacht areas of the counties of Cork (Contae Chorcaí), Kerry (Contae Chiarraí), and Waterford (Contae Phort Láirge). The Gaeltacht areas of Cork can be found in Cape Clear Island (Oileán Chléire) and Muskerry (Múscraí); those of Kerry lie in Corca Dhuibhne and Iveragh Peninsula; and those of Waterford in Ring (An Rinn) and Old Parish (An Sean Phobal), both of which together form Gaeltacht na nDéise. Of the three counties, the Irish spoken in Cork and Kerry is quite similar while that of Waterford is more distinct.

Some typical features of Munster Irish are:

- The use of synthetic verbs in parallel with a pronominal subject system, thus "I must" is caithfead in Munster, while other dialects prefer caithfidh mé (mé means "I"). "I was" and "you were" are bhíos and bhís in Munster but more commonly bhí mé and bhí tú in other dialects. These are strong tendencies, and the personal forms bhíos etc. are used in the West and North, particularly when the words are last in the clause.

- Use of independent/dependent forms of verbs that are not included in the Standard. For example, "I see" in Munster is chím, which is the independent form; Ulster Irish also uses a similar form, tchím, whereas "I do not see" is ní fheicim, feicim being the dependent form, which is used after particles such as ní ("not"). Chím is replaced by feicim in the Standard. Similarly, the traditional form preserved in Munster bheirim "I give"/ní thugaim is tugaim/ní thugaim in the Standard; gheibhim I get/ní bhfaighim is faighim/ní bhfaighim.

- When before ⟨ll, m, nn, rr, rd⟩ and so on, in monosyllabic words and in the stressed syllable of multisyllabic words where the syllable is followed by a consonant, some short vowels are lengthened while others are diphthongised, in ceann [cɑun̪ˠ] "head", cam [kɑumˠ] "crooked", gearr [ɟɑːɾˠ] "short", ord [oːɾˠd̪ˠ] "sledgehammer", gall [gɑul̪ˠ] "foreigner, non-Gael", iontas [uːn̪ˠt̪ˠəsˠ] "a wonder, a marvel", compánach [kəumˠˈpˠɑːnˠəx] "companion, mate", etc.

- A copular construction involving ea "it" is frequently used. Thus "I am an Irish person" can be said is Éireannach mé and Éireannach is ea mé in Munster; there is a subtle difference in meaning, however, the first choice being a simple statement of fact, while the second brings emphasis onto the word Éireannach. In effect the construction is a type of "fronting".

- Both masculine and feminine words are subject to lenition after insan (sa/san) "in the", den "of the", and don "to/for the": sa tsiopa "in the shop", compared to the Standard sa siopa (the Standard lenites only feminine nouns in the dative in these cases).

- Eclipsis of ⟨f⟩ after sa: sa bhfeirm, "in the farm", instead of san fheirm.

- Eclipsis of ⟨t⟩ and ⟨d⟩ after preposition + singular article, with all prepositions except after insan, den and don: ar an dtigh "on the house", ag an ndoras "at the door".

- Stress is generally on the second syllable of a word when the first syllable contains a short vowel, and the second syllable contains a long vowel or diphthong, or is -⟨(e)ach⟩, e.g. Ciarán is pronounced [ciəˈɾˠaːn̪ˠ] opposed to [ˈciəɾˠaːn̪ˠ] in Connacht and Ulster.

Ulster

[edit]Ulster Irish is the dialect spoken in the Gaeltacht regions of Donegal. These regions contain all of Ulster's communities where Irish has been spoken in an unbroken line back to when the language was the dominant language of Ireland. The Irish-speaking communities in other parts of Ulster are a result of language revival – English-speaking families deciding to learn Irish. Census data shows that 4,130 people speak it at home.[citation needed]

Linguistically, the most important of the Ulster dialects today is that which is spoken, with slight differences, in both Gweedore (Gaoth Dobhair = Inlet of Streaming Water) and The Rosses (na Rossa).[citation needed]

Ulster Irish sounds quite different from the other two main dialects. It shares several features with southern dialects of Scottish Gaelic and Manx, as well as having many characteristic words and shades of meanings. However, since the demise of those Irish dialects spoken natively in what is today Northern Ireland, it is probably an exaggeration to see present-day Ulster Irish as an intermediary form between Scottish Gaelic and the southern and western dialects of Irish. Northern Scottish Gaelic has many non-Ulster features in common with Munster Irish.[citation needed]

One noticeable trait of Ulster Irish, Scots Gaelic and Manx is the use of the negative particle cha(n) in place of the Munster and Connacht ní. Though southern Donegal Irish tends to use ní more than cha(n), cha(n) has almost ousted ní in northernmost dialects (e.g. Rosguill and Tory Island), though even in these areas níl "is not" is more common than chan fhuil or cha bhfuil.[93][94] Another noticeable trait is the pronunciation of the first person singular verb ending -(a)im as -(e)am, also common to the Isle of Man and Scotland (Munster/Connacht siúlaim "I walk", Ulster siúlam).[citation needed]

Leinster

[edit]Down to the early 19th century and even later, Irish was spoken in all twelve counties of Leinster. The evidence furnished by placenames, literary sources and recorded speech can be interpreted that there was no Leinster dialect as such. Instead, the main dialect used in the province was represented by a broad central belt stretching from west Connacht eastwards to the Liffey estuary and southwards to Wexford, though with many local variations. Two smaller dialect areas were represented by the Ulster speech of counties Meath and Louth, which extended as far south as the Boyne valley, and a Munster dialect found in Kilkenny and south Laois.[citation needed]

This main dialect had characteristics which survive today only in the Irish of Connacht. It typically placed the stress on the first syllable of a word, and showed a preference (found in placenames) for the pronunciation ⟨cr⟩ where the standard spelling is ⟨cn⟩. The word cnoc (hill) would therefore be pronounced croc. Examples are the placenames Crooksling (Cnoc Slinne) in County Dublin and Crukeen (Cnoicín) in Carlow. Speakers in East Leinster showed the same diphthongisation or vowel lengthening as in Munster and Connacht Irish in words like poll (hole), cill (monastery), coill (wood), ceann (head), cam (crooked) and dream (crowd).[citation needed] A feature of the dialect was the pronunciation of ⟨ao⟩, which generally became [eː] in east Leinster (as in Munster), and [iː] in the west (as in Connacht).[95]

Early evidence regarding colloquial Irish in east Leinster is found in The Fyrst Boke of the Introduction of Knowledge (1547), by the English physician and traveller Andrew Borde.[96] The illustrative phrases he uses include the following:

| English | Leinster Irish | |

|---|---|---|

| Anglicised spelling | Irish spelling | |

| How are you? | Kanys stato? | [Conas 'tá tú?] |

| I am well, thank you | Tam a goomah gramahagood. | [Tá mé go maith, go raibh maith agat.] |

| Sir, can you speak Irish? | Sor, woll galow oket? | [Sir, 'bhfuil Gaeilig [Gaela'] agat?] |

| Wife, give me bread! | Benytee, toor haran! | [A bhean an tí, tabhair arán!] |

| How far is it to Waterford? | Gath haad o showh go part laarg?. | [Gá fhad as [a] seo go Port Láirge?] |

| It is one a twenty mile. | Myle hewryht. | [Míle a haon ar fhichid.] |

| When shall I go to sleep, wife? | Gah hon rah moyd holow? | [Gathain a rachamaoid a chodladh?] |

The Pale

[edit]

The Pale (An Pháil) was an area around late medieval Dublin under the control of the English government. By the late 15th century it consisted of an area along the coast from Dalkey, south of Dublin, to the garrison town of Dundalk, with an inland boundary encompassing Naas and Leixlip in the Earldom of Kildare and Trim and Kells in County Meath to the north. In this area of "Englyshe tunge" English had never actually been a dominant language – and was moreover a relatively late comer; the first colonisers were Normans who spoke Norman French, and before these Norse. The Irish language had always been the language of the bulk of the population. An English official remarked of the Pale in 1515 that "all the common people of the said half counties that obeyeth the King's laws, for the most part be of Irish birth, of Irish habit and of Irish language".[97]

With the strengthening of English cultural and political control, language change began to occur but this did not become clearly evident until the 18th century. Even then, in the decennial period 1771–1781, the percentage of Irish speakers in Meath was at least 41%. By 1851 this had fallen to less than 3%.[98]

General decline

[edit]English expanded strongly in Leinster in the 18th century but Irish speakers were still numerous. In the decennial period 1771–1781 certain counties had estimated percentages of Irish speakers as follows (though the estimates are likely to be too low):[98]

- Kilkenny 57%

- Louth 57%

- Longford 22%

- Westmeath 17%

The language saw its most rapid initial decline in counties Dublin, Kildare, Laois, Wexford, and Wicklow. In recent years, County Wicklow has been noted as having the lowest percentage of Irish speakers of any county in Ireland, with only 0.14% of its population claiming to have passable knowledge of the language.[99] The proportion of Irish-speaking children in Leinster went down as follows: 17% in the 1700s, 11% in the 1800s, 3% in the 1830s, and virtually none in the 1860s.[100] The Irish census of 1851 showed that there were still a number of older speakers in County Dublin.[98] Sound recordings were made between 1928 and 1931 of some of the last speakers in Omeath, County Louth (now available in digital form).[101] The last known traditional native speaker in Omeath, and in Leinster as a whole, was Annie O'Hanlon (née Dobbin), who died in 1960.[30] Her dialect was, in fact, a branch of the Irish of south-east Ulster.[102]

Urban use from the Middle Ages to the 19th century

[edit]Irish was spoken as a community language in Irish towns and cities down to the 19th century. In the 16th and 17th centuries it was widespread even in Dublin and the Pale. The English administrator William Gerard (1518–1581) commented as follows: "All English, and the most part with delight, even in Dublin, speak Irish",[103] while the Old English historian Richard Stanihurst (1547–1618) lamented that "When their posterity became not altogether so wary in keeping, as their ancestors were valiant in conquering, the Irish language was free dennized in the English Pale: this canker took such deep root, as the body that before was whole and sound, was by little and little festered, and in manner wholly putrified".[104]

The Irish of Dublin, situated as it was between the east Ulster dialect of Meath and Louth to the north and the Leinster-Connacht dialect further south, may have reflected the characteristics of both in phonology and grammar. In County Dublin itself the general rule was to place the stress on the initial vowel of words. With time it appears that the forms of the dative case took over the other case endings in the plural (a tendency found to a lesser extent in other dialects). In a letter written in Dublin in 1691 we find such examples as the following: gnóthuimh (accusative case, the standard form being gnóthaí), tíorthuibh (accusative case, the standard form being tíortha) and leithscéalaibh (genitive case, the standard form being leithscéalta).[105]

English authorities of the Cromwellian period, aware that Irish was widely spoken in Dublin, arranged for its official use. In 1655 several local dignitaries were ordered to oversee a lecture in Irish to be given in Dublin. In March 1656 a converted Catholic priest, Séamas Corcy, was appointed to preach in Irish at Bride's parish every Sunday, and was also ordered to preach at Drogheda and Athy.[106] In 1657 the English colonists in Dublin presented a petition to the Municipal Council complaining that in Dublin itself "there is Irish commonly and usually spoken".[107]

There is contemporary evidence of the use of Irish in other urban areas at the time. In 1657 it was found necessary to have an Oath of Abjuration (rejecting the authority of the Pope) read in Irish in Cork so that people could understand it.[108]

Irish was sufficiently strong in early 18th century Dublin to be the language of a coterie of poets and scribes led by Seán and Tadhg Ó Neachtain, both poets of note.[109] Scribal activity in Irish persisted in Dublin right through the 18th century. An outstanding example was Muiris Ó Gormáin (Maurice Gorman), a prolific producer of manuscripts who advertised his services (in English) in Faulkner's Dublin Journal.[110] There were still an appreciable number of Irish speakers in County Dublin at the time of the 1851 census.[111]

In other urban centres the descendants of medieval Anglo-Norman settlers, the so-called Old English, were Irish-speaking or bilingual by the 16th century.[112] The English administrator and traveller Fynes Moryson, writing in the last years of the 16th century, said that "the English Irish and the very citizens (excepting those of Dublin where the lord deputy resides) though they could speak English as well as we, yet commonly speak Irish among themselves, and were hardly induced by our familiar conversation to speak English with us".[113] In Galway, a city dominated by Old English merchants and loyal to the Crown up to the Irish Confederate Wars (1641–1653), the use of the Irish language had already provoked the passing of an Act of Henry VIII (1536), ordaining as follows:

- Item, that every inhabitant within oure said towne [Galway] endeavour themselfes to speake English, and to use themselfes after the English facon; and, speciallye, that you, and every one of you, doe put your children to scole, to lerne to speke English...[114]

The demise of native cultural institutions in the seventeenth century saw the social prestige of Irish diminish, and the gradual Anglicisation of the middle classes followed.[115] The census of 1851 showed, however, that the towns and cities of Munster still had significant Irish-speaking populations. Much earlier, in 1819, James McQuige, a veteran Methodist lay preacher in Irish, wrote: "In some of the largest southern towns, Cork, Kinsale and even the Protestant town of Bandon, provisions are sold in the markets, and cried in the streets, in Irish".[116] Irish speakers constituted over 40% of the population of Cork even in 1851.[117]

Modern urban usage

[edit]The late 18th and 19th centuries saw a reduction in the number of Dublin's Irish speakers, in keeping with the trend elsewhere. This continued until the end of the 19th century, when the Gaelic revival saw the creation of a strong Irish–speaking network, typically united by various branches of the Conradh na Gaeilge, and accompanied by renewed literary activity.[118] By the 1930s Dublin had a lively literary life in Irish.[119]

Urban Irish has been the beneficiary, from the last decades of the 20th century, of a rapidly expanding system of Gaelscoileanna, teaching entirely through Irish. As of 2019 there are 37 such primary schools in Dublin alone.[120]

It has been suggested that Ireland's towns and cities are acquiring a critical mass of Irish speakers, reflected in the expansion of Irish language media.[121] Many are younger speakers who, after encountering Irish at school, made an effort to acquire fluency, while others have been educated through Irish and some have been raised with Irish. Those from an English-speaking background are now often described as nuachainteoirí ("new speakers") and use whatever opportunities are available (festivals, "pop-up" events) to practise or improve their Irish.[122]

It has been suggested that the comparative standard is still the Irish of the Gaeltacht,[123] but other evidence suggests that young urban speakers take pride in having their own distinctive variety of the language.[124] A comparison of traditional Irish and urban Irish shows that the distinction between broad and slender consonants, which is fundamental to Irish phonology and grammar, is not fully or consistently observed in urban Irish. This and other changes make it possible that urban Irish will become a new dialect or even, over a long period, develop into a creole (i.e. a new language) distinct from Gaeltacht Irish.[121] It has also been argued that there is a certain elitism among Irish speakers, with most respect being given to the Irish of native Gaeltacht speakers and with "Dublin" (i.e. urban) Irish being under-represented in the media.[125] This, however, is paralleled by a failure among some urban Irish speakers to acknowledge grammatical and phonological features essential to the structure of the language.[121]

Standardisation

[edit]There is no single official standard for pronouncing the Irish language. Certain dictionaries, such as Foclóir Póca, provide a single pronunciation. Online dictionaries such as Foclóir Béarla-Gaeilge[126] provide audio files in the three major dialects. The differences between dialects are considerable, and have led to recurrent difficulties in conceptualising a "standard Irish." In recent decades contacts between speakers of different dialects have become more frequent and the differences between the dialects are less noticeable.[127]

An Caighdeán Oifigiúil ("The Official Standard"), often shortened to An Caighdeán, is a standard for the spelling and grammar of written Irish, developed and used by the Irish government. Its rules are followed by most schools in Ireland, though schools in and near Irish-speaking regions also use the local dialect. It was published by the translation department of Dáil Éireann in 1953[128] and updated in 2012[129] and 2017.

Phonology

[edit]In pronunciation, Irish most closely resembles its nearest relatives, Scottish Gaelic and Manx. One notable feature is that consonants (except /h/) come in pairs, one "broad" (velarised, pronounced with the back of the tongue pulled back towards the soft palate) and one "slender" (palatalised, pronounced with the middle of the tongue pushed up towards the hard palate). While broad–slender pairs are not unique to Irish (being found, for example, in Russian and Lithuanian), in Irish they have a grammatical function.

| Labial | Coronal | Dorsal | Glottal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| broad | slender | broad | slender | broad | slender | |||

| Stop | voiceless | pˠ | pʲ | t̪ˠ | tʲ | k | c | |

| voiced | bˠ | bʲ | d̪ˠ | dʲ | ɡ | ɟ | ||

| Continuant | voiceless | fˠ | fʲ | sˠ | ʃ | x | ç | h |

| voiced | w | vʲ | l̪ˠ | lʲ | ɣ | j | ||

| Nasal | mˠ | mʲ | n̪ˠ | nʲ | ŋ | ɲ | ||

| Tap | ɾˠ | ɾʲ | ||||||

| Front | Central | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | short | long | |

| Close | ɪ | iː | ʊ | uː | |

| Mid | ɛ | eː | ə | ɔ | oː |

| Open | a | ɑː | |||

The diphthongs of Irish are /iə, uə, əi, əu/.

Syntax and morphology

[edit]Irish is a fusional, VSO, nominative-accusative language. It is neither verb nor satellite framed, and makes liberal use of deictic verbs.

Nouns decline for 3 numbers: singular, dual (only in conjunction with the number dhá "two"), plural; 2 genders: masculine, feminine; and 4 cases: nomino-accusative (ainmneach), vocative (gairmeach), genitive (ginideach), and prepositional-locative (tabharthach), with fossilised traces of the older accusative (cuspóireach). Adjectives agree with nouns in number, gender, and case. Adjectives generally follow nouns, though some precede or prefix nouns. Demonstrative adjectives have proximal, medial, and distal forms. The prepositional-locative case is called the dative by convention, though it originates in the Proto-Celtic ablative.

Verbs conjugate for 3 tenses: past, present, future; 2 aspects: perfective, imperfective; 2 numbers: singular, plural; 4 moods: indicative, subjunctive, conditional, imperative; 2 relative forms, the present and future relative; and in some verbs, independent and dependent forms. Verbs conjugate for 3 persons and an impersonal form which is actor-free; the 3rd person singular acts as a person-free personal form that can be followed or otherwise refer to any person or number.

There are two verbs for "to be", one for inherent qualities with only two forms, is "present" and ba "past" and "conditional", and one for transient qualities, with a full complement of forms except for the verbal adjective. The two verbs share the one verbal noun.

Irish verb formation employs a mixed system during conjugation, with both analytic and synthetic methods employed depending on tense, number, mood and person. For example, in the official standard, present tense verbs have conjugated forms only in the 1st person and autonomous forms (i.e. molaim 'I praise', molaimid 'we praise', moltar 'is praised, one praises' ), whereas all other persons are conveyed analytically (i.e. molann sé 'he praises', molann sibh 'you pl. praise'). The ratio of analytic to synthetic forms in a given verb paradigm varies between the various tenses and moods. The conditional, imperative and past habitual forms prefer synthetic forms in most persons and numbers, whereas the subjunctive, past, future and present forms prefer mostly analytical forms.

The meaning of the passive voice is largely conveyed through the autonomous verb form, however there also exist other structures analogous to the passival and resultative constructions. There are also a number of preverbal particles marking the negative, interrogative, subjunctive, relative clauses, etc. There is a verbal noun and verbal adjective. Verb forms are highly regular, many grammars recognise only 11 irregular verbs.

Prepositions inflect for person and number. Different prepositions govern different cases. In Old and Middle Irish, prepositions governed different cases depending on intended semantics; this has disappeared in Modern Irish except in fossilised form.

Irish has no verb to express having; instead, the word ag ("at", etc.) is used in conjunction with the transient "be" verb bheith:

- Tá leabhar agam. "I have a book." (Literally, "there is a book at me", cf. Russian У меня есть книга, Finnish minulla on kirja, French le livre est à moi)

- Tá leabhar agat. "You (singular) have a book."

- Tá leabhar aige. "He has a book."

- Tá leabhar aici. "She has a book."

- Tá leabhar againn. "We have a book."

- Tá leabhar agaibh. "You (plural) have a book."

- Tá leabhar acu. "They have a book."

Numerals have three forms: abstract, general and ordinal. The numbers from 2 to 10 (and these in combination with higher numbers) are rarely used for people, numeral nominals being used instead:

- a dó "Two."

- dhá leabhar "Two books."

- beirt "Two people, a couple", beirt fhear "Two men", beirt bhan "Two women".

- dara, tarna (free variation) "Second."

Irish has both decimal and vigesimal systems:

- 10: a deich

- 20: fiche

- 30: vigesimal – a deich is fiche; decimal – tríocha

- 40: v. daichead, dá fhichead; d. ceathracha

- 50: v. a deich is daichead; d. caoga (also: leathchéad "half-hundred")

- 60: v. trí fichid; d. seasca

- 70: v. a deich is trí fichid; d. seachtó

- 80: v. cheithre fichid; d. ochtó

- 90: v. a deich is cheithre fichid; d. nócha

- 100: v. cúig fichid; d. céad

A number such as 35 has various forms:

- a cúigdéag is fichid "15 and 20"

- a cúig is tríocha "5 and 30"

- a cúigdéag ar fhichid "15 on 20"

- a cúig ar thríochaid "5 on 30"

- a cúigdéag fichead "15 of 20 (genitive)"

- a cúig tríochad "5 of 30 (genitive)"

- fiche 's a cúigdéag "20 and 15"

- tríocha 's a cúig "30 and 5"

The latter is most commonly used in mathematics.

Initial mutations

[edit]In Irish, there are two classes of initial consonant mutations, which express grammatical relationship and meaning in verbs, nouns and adjectives:

- Lenition (séimhiú) describes the change of stops into fricatives.[130] Indicated in Gaelic type by an overdot (ponc séimhithe), it is shown in Roman type by adding an ⟨h⟩.

- caith! "throw!" – chaith mé "I threw" (lenition as a past-tense marker, caused by the particle do, now generally omitted)

- gá "requirement" – easpa an ghá "lack of the requirement" (lenition marking the genitive case of a masculine noun)

- Seán "John" – a Sheáin! "John!" (lenition as part of the vocative case, the vocative lenition being triggered by a, the vocative marker before Sheáin)

- Eclipsis (urú) covers the voicing of voiceless stops, and nasalisation of voiced stops.

- Athair "Father" – ár nAthair "our Father"

- tús "start", ar dtús "at the start"

- Gaillimh "Galway" – i nGaillimh "in Galway"

Mutations are often the only way to distinguish grammatical forms. For example, the only non-contextual way to distinguish possessive pronouns "her", "his" and "their", is through initial mutations since all meanings are represented by the same word a.

- his shoe – a bhróg (lenition)

- their shoe – a mbróg (eclipsis)

- her shoe – a bróg (unchanged)

Due to initial mutation, prefixes, clitics, suffixes, root inflection, ending morphology, elision, sandhi, epenthesis, and assimilation; the beginning, core, and end of words can each change radically and even simultaneously depending on context.

Orthography

[edit]

A native writing system, Ogham, was used to write Primitive Irish and Old Irish until Latin script was introduced in the 5th century CE.[131] Since the introduction of Latin script, the main typeface used to write Irish was Gaelic type until it was replaced by Roman type during the mid-20th century.

The traditional Irish alphabet (áibítir) consists of 18 letters: ⟨a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, l, m, n, o, p, r, s, t, u⟩; it does not contain ⟨j, k, q, v, w, x, y, z⟩.[132][133] However, contemporary Irish uses the full Latin alphabet, with the previously unused letter used in modern loanwords; ⟨v⟩ occurs in a small number of (mainly onomatopoeic) native words and colloquialisms.

Vowels may be accented with an acute accent (⟨á, é, í, ó, ú⟩; Irish and Hiberno-English: (síneadh) fada "long (sign)"), but it is ignored for purposes of alphabetisation.[134] It is used, among other conventions, to mark long vowels, e.g. ⟨e⟩ is /ɛ/ and ⟨é⟩ is /eː/.

The overdot (ponc séimhithe "dot of lenition") was used in traditional orthography to indicate lenition; An Caighdeán uses a following ⟨h⟩ for this purpose, i.e. the dotted letters (litreacha buailte "struck letters") ⟨ḃ, ċ, ḋ, ḟ, ġ, ṁ, ṗ, ṡ, ṫ⟩ are equivalent to ⟨bh, ch, dh, fh, gh, mh, ph, sh, th⟩.

The use of Gaelic type and the overdot today is restricted to when a traditional style is consciously being used, e.g. Óglaiġ na h-Éireann on the Irish Defence Forces cap badge (see above). Extending the use of the overdot to Roman type would theoretically have the advantage of making Irish texts significantly shorter, e.g. gheobhaidh sibh "you (pl.) will get" would become ġeoḃaiḋ siḃ.

Spelling reform

[edit]Around the time of the Second World War, Séamas Daltún, in charge of Rannóg an Aistriúcháin (The Translation Department of the Irish government), issued his own guidelines about how to standardise Irish spelling and grammar. This de facto standard was subsequently approved by the State and developed into An Caighdeán Oifigiúil, which simplified and standardised the orthography and grammar by removing inter-dialectal silent letters and simplifying vowel combinations. Where multiple versions existed in different dialects for the same word, one was selected, for example:

- beirbhiughadh → beiriú "cook"

- biadh → bia "food"

- Gaedhealg / Gaedhilg / Gaedhealaing / Gaeilic / Gaelainn / Gaoidhealg / Gaolainn → Gaeilge "Irish language"

An Caighdeán does not reflect all dialects to the same degree, e.g. cruaidh /kɾˠuəj/ "hard", leabaidh /ˈl̠ʲabˠəj/ "bed", and tráigh /t̪ˠɾˠaːj/ "beach" were standardised as crua, leaba, and trá despite the reformed spellings only reflecting South Connacht realisations [kɾˠuə], [ˈl̠ʲabˠə], and [t̪ˠɾˠaː], failing to represent the other dialectal realisations [kɾˠui], [ˈl̠ʲabˠi], and [t̪ˠɾˠaːi] (in Mayo and Ulster) or [kɾˠuəɟ], [ˈl̠ʲabˠəɟ], and [t̪ˠɾˠaːɟ] (in Munster), which were previously represented by the pre-reformed spellings.[135] For this reason, the pre-reform spellings are used by some speakers to reflect the dialectal pronunciations.

Other examples include the genitive of bia "food" (/bʲiə/; pre-reform biadh) and saol "life, world" (/sˠeːlˠ/; pre-reform saoghal), realised [bʲiːɟ] and [sˠeːlʲ] in Munster, reflecting the pre-Caighdeán spellings bídh and saoghail, which were standardised as bia and saoil despite not representing the Munster pronunciations.[136][137]

Sample text

[edit]Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

| Irish: Saolaítear gach duine den chine daonna saor agus comhionann i ndínit agus i gcearta. Tá bua an réasúin agus an choinsiasa acu agus ba cheart dóibh gníomhú i dtreo a chéile i spiorad an bhráithreachais.[138] |

English: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.[139] |

See also

[edit]- Buntús Cainte, a course in basic spoken Irish

- Comparison of Scottish Gaelic and Irish

- Cumann Gaelach, Irish language Society

- Dictionary of the Irish Language

- English loanwords in Irish

- Fáinne, a lapel pin for Irish speakers

- Goidelic substrate hypothesis

- Hiberno-Latin, a variety of Medieval Latin used in Irish monasteries. It included Greek, Hebrew and Celtic neologisms.

- Irish language outside Ireland

- Irish name and Place names in Ireland

- Irish words used in the English language

- Irish, a subject of the Junior Cycle examination in Secondary schools in Ireland

- List of artists who have released Irish-language songs

- List of English words of Irish origin

- List of Ireland-related topics

- List of Irish-language given names

- List of Irish-language media

- Modern literature in Irish

- Status of the Irish language, a detailed account of the current state of the language.

- Teastas Eorpach na Gaeilge

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b "Constitution of Ireland". Government of Ireland. 1 July 1937. Archived from the original on 17 July 2009. Retrieved 19 June 2007.

- ^ a b Ainsworth, Paul (6 December 2022). "'Historic milestone' passed as Irish language legislation becomes law". The Irish News. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ^ Moseley, Christopher; Nicolas, Alexander, eds. (2010). Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger (PDF) (3rd ed.). Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-104096-2. Archived from the original on 23 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Gaelic". Cambridge English Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- ^ "Irish Language at UW-Milwaukee". Center for Celtic Studies. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ O'Gallagher, J. (1877). Sermons in Irish-Gaelic. Gill.

- ^ "Our Role Supporting You". Foras na Gaeilge. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

... between Foras na Gaeilge and Bòrd na Gàidhlig, promoting the use of Irish Gaelic and Scottish Gaelic in Ireland and Scotland ...'

- ^ a b "Gaelic: Definition of Gaelic by Merriam-Webster". Merriam-Webster.com. Merriam-Webster, Incorporated.

- ^ a b "Gaelic definition and meaning". Collins English Dictionary.

- ^ "Reawakening the Irish Language through the Irish Education System: Challenges and Priorities" (PDF). International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education.

- ^ a b c d "Irish Language and the Gaeltacht". CSO – Central Statistics Office. 19 December 2023.

- ^ "Frequency of Speaking Irish". nisra.gov.uk. 21 March 2023.

- ^ a b "1. Detailed Languages Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and Over for the United States: 2006–2008", Language (table), Census, 2010

- ^ Doyle, Danny (2015). Míle Míle i gCéin: The Irish Language in Canada. Ottawa: Borealis Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-88887-631-7.

- ^ Dinneen, Patrick S. (1927). Foclóir Gaedhilge agus Béarla [Irish and English dictionary] (in Irish) (2d ed.). Dublin: Irish Texts Society. pp. 507 s.v. Gaedhealg. ISBN 1-870166-00-0.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Hamilton, John (1974). A Phonetic Study of the Irish of Tory Island. The Queen's University of Belfast. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-85389-161-1.

- ^ Doyle, Aidan; Gussmann, Edmund (2005). An Ghaeilge, Podręcznik Języka Irlandzkiego. Redakcja Wydawnictw Katolickiego Uniwersytetu Lubelskiego. pp. 423k. ISBN 83-7363-275-1.

- ^ Dillon, Myles; Ó Cróinín, Donncha (1961). Teach Yourself Irish. London: English Universities Press. p. 227.

- ^ Ó Dónaill, Niall, ed. (1977). Foclóir Gaeilge–Béarla. p. 600 s.v. Gaeilge.

- ^ "Ireland speaks up loudly for Gaelic". The New York Times. 29 March 2005. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2017. An example of the use of the word "Gaelic" to describe the language, seen throughout the text of the article.

- ^ "Irish: Ethnologue". Ethnologue. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

Alternate names: Erse, Gaelic Irish, Irish Gaelic

- ^ Dalton, Martha (July 2019). "Nuclear Accents in Four Irish (Gaelic) Dialects". International Conference of Phonetic Science. XVI. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.486.4615.

- ^ "Interinstitutional Style Guide: Section 7.2.4. Rules governing the languages of the institutions". European Union. 27 April 2016.

- ^ "Gaelic". The Free Dictionary.

- ^ "House of Commons, 1 August 1922: Ireland: Erse language (18)". Hansard. 157. London, UK: Houses of Parliament. 1240–1242. 1 August 1922.

Sir CHARLES OMAN asked the Secretary of State for the Colonies whether he has protested against the recent attempt of the Provisional Government in Ireland to force compulsory Erse into all official correspondence, in spite of the agreement that Erse and English should be equally permissible .. MR CHURCHILL .. I do not anticipate that Irish Ministers will willingly incur the very great confusion which would inevitably result from the use of Irish for the material parts of their correspondence.

- ^ Irving, Jenni. "Ogham". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ Doyle, Aidan (2015). A History of the Irish Language: From the Norman Invasion to Independence. Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-872476-6. Retrieved 26 September 2024.

Modern Irish (MI), sometimes called Late Modern Irish (LMI), is regarded as beginning about 1600 and extending to the present day.

- ^ Doyle, Aidan (2015). A History of the Irish Language: From the Norman Invasion to Independence. Oxford University Press. pp. 75–77. ISBN 978-0-19-872476-6. Retrieved 26 September 2024.

- ^ De Fréine, Seán (1978). The Great Silence: The Study of a Relationship Between Language and Nationality. Irish Books & Media. ISBN 978-0-85342-516-8.

- ^ a b Ó Gráda 2013.

- ^ O'Reilly, Edward (17 March 2015). ""The unadulterated Irish language": Irish Speakers in Nineteenth Century New York". New-York Historical Society. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- ^ See the discussion in Wolf, Nicholas M. (2014). An Irish-Speaking Island: State, Religion, Community, and the Linguistic Landscape in Ireland, 1770–1870. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-30274-0.

- ^ McMahon 2008, pp. 130–131.

- ^ "The Irish language and the Church of Ireland". Church of Ireland. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- ^ Watson, Iarfhlaith; Nic Ghiolla Phádraig, Máire (September 2009). "Is there an educational advantage to speaking Irish? An investigation of the relationship between education and ability to speak Irish". International Journal of the Sociology of Language (199): 143–156. doi:10.1515/IJSL.2009.039. hdl:10197/5649. S2CID 144222872.

- ^ Blackshire-Belay, Carol (23 February 1994). Current Issues in Second Language Acquisition and Development. University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-8191-9182-3. Retrieved 23 February 2025 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Ireland speaks up loudly for Gaelic". The New York Times. 29 March 2005. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ Murphy, Brian (25 January 2018). "Douglas Hyde's inauguration – a signal of a new Ireland". RTÉ. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^ a b "Douglas Hyde Opens 2RN 1 January 1926". RTÉ News. 15 February 2012. Archived from the original on 6 January 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ^ "Allocution en irlandais, par M. Douglas Hyde". Bibliothèque nationale de France. 28 January 1922. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^ "The Doegen Records Web Project". Archived from the original on 7 September 2018.

- ^ "Census of Population 2016 – Profile 10 Education, Skills and the Irish Language". CSO – Central Statistics Office. 23 November 2017. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ Ó Murchú, Máirtín (1993). "Aspects of the societal status of Modern Irish". In Ball, Martin J.; Fife, James (eds.). The Celtic Languages. London: Routledge. pp. 471–90. ISBN 0-415-01035-7.

- ^ "NUI Entry Requirements –". Ollscoil na hÉireann – National University of Ireland. Archived from the original on 5 July 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ "Obligation to appoint Irish speakers". Archived from the original on 30 November 2005.

- ^ Wilson, Jade (26 June 2024). "University of Galway president Ciarán Ó hÓgartaigh to step down from his role". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2 August 2024.

- ^ "Academic claims the forced learning of Irish 'has failed'". Independent.ie. 19 January 2006.

- ^ Regan, Mary (4 May 2010). "End compulsory Irish, says FG, as 14,000 drop subject". Irish Examiner.

- ^ Donncha Ó hÉallaithe: "Litir oscailte chuig Enda Kenny": BEO.ie Archived 20 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Siggins, Lorna (16 July 2007). "Study sees decline of Irish in Gaeltacht". The Irish Times.

- ^ Nollaig Ó Gadhra, 'The Gaeltacht and the Future of Irish, Studies, Volume 90, Number 360

- ^ Welsh Robert and Stewart, Bruce (1996). 'Gaeltacht,' The Oxford Companion to Irish Literature. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Hindley, Reg (1991). The Death of the Irish Language: A Qualified Obituary. Taylor & Francis.

- ^ Magan, Manchán (9 January 2007). "Cá Bhfuil Na Gaeilg eoirí? *". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 29 January 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ "Why choose Irish-medium education? | Gaeloideachas". gaeloideachas.ie. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ See the discussion and the conclusions reached in 'Language and Occupational Status: Linguistic Elitism in the Irish Labour Market,' The Economic and Social Review, Vol. 40, No. 4, Winter, 2009, pp. 435–460: Ideas.repec.org Archived 29 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Over 2.3m people using language app to learn Irish". RTÉ. 25 November 2016. Archived from the original on 4 September 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ "Ar fheabhas! President praises volunteer Duolingo translators". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ a b Siggins, Lorna (6 January 2003). "Only 25% of Gaeltacht households fluent in Irish – survey". The Irish Times. p. 5.

- ^ Hindley 1991, Map 7: Irish speakers by towns and distinct electoral divisions, census 1926.

- ^ "The Gaeltacht | Our Language & the Ghaeltacht". Údarás na Gaeltachta. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ "Gaeltacht Affairs". Gov.ie. Department of Rural and Community Development and the Gaeltacht. 30 September 2025 [2020-10-05]. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ a b Trinity College Dublin (5 November 2020). "Official Languages Act 2003".

- ^ "Official Languages Act 2003". www.gov.ie. 22 July 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ An Coimisinéir Teanga. Official Languages Act 2003: Guidebook (PDF). pp. 1–3.

- ^ "Official Languages Act 2003 (and related legislation)". Gov.ie. 31 August 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "Review of Official Language Act 2003". Gov.ie. 3 July 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "Irish Language Policy". Gov.ie. July 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ Roinn an Taoisigh (2019). Official Languages Act 2003: Language Scheme 2019–2022. p. 3.

- ^ Seán Ó Briain (22 December 2010). Straitéis 20 Bliain don Ghaeilge. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ "Taoiseach launches 20-Year Strategy for the Irish Language 2010–2030". Department of the Taoiseach. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ Breadun, Deaglan De. "Plan could treble number speaking Irish, says Cowen". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ a b Government of Ireland (2010). 20-Year Strategy for the Irish Language 2010–2030. p. 11.

- ^ "Action Plan for the Irish Language launched by Minister of State McHugh". Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ "CAIN: Issues: Language: O'Reilly, C. (1997) Nationalists and the Irish Language in Northern Ireland: Competing Perspectives". CAIN. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ^ "GPPAC.net". Archived from the original on 13 May 2007.

- ^ "Belfast Agreement – Full text – Section 6 (Equality) – "Economic, Social and Cultural issues"". CAIN. Archived from the original on 22 November 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ "Irish language future is raised". BBC News. 13 December 2006. Archived from the original on 15 March 2007. Retrieved 19 June 2007.

- ^ "Thousands call for Irish Language Act during Belfast rally". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ "Is í an Ghaeilge an 21ú teanga oifigiúil den Aontas Eorpach" [Irish is the 21st official language of the European Union] (in Irish). Archived from the original on 18 March 2008. Retrieved 14 June 2008.

- ^ Boland, Lauren (31 December 2021). "Irish to be fully recognised as an official EU language from New Year's Day". TheJournal.ie. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ O Broin, Brian. "An Analysis of the Irish-Speaking Communities of North America: Who are they, what are their opinions, and what are their needs?". Academia (in Irish). Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2012.