Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Three Laws of Robotics

View on Wikipedia| Laws of robotics |

|---|

| Isaac Asimov |

| Related topics |

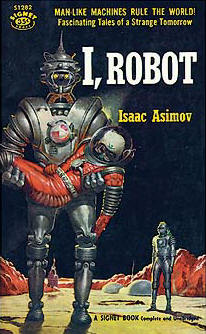

The Three Laws of Robotics (often shortened to The Three Laws or Asimov's Laws) are a set of rules devised by science fiction author Isaac Asimov, which were to be followed by robots in several of his stories. The rules were introduced in his 1942 short story "Runaround" (included in the 1950 collection I, Robot), although similar restrictions had been implied in earlier stories.

The Laws

[edit]The Three Laws, presented to be from the fictional "Handbook of Robotics, 56th Edition, 2058 A.D.", are:[1]

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

Use in fiction

[edit]The Three Laws form an organizing principle and unifying theme for Asimov's robot-based fiction, appearing in his Robot series, the stories linked to it, and in his (initially pseudonymous) Lucky Starr series of young-adult fiction. The Laws are incorporated into almost all of the positronic robots appearing in his fiction, and cannot be bypassed, being intended as a safety feature. A number of Asimov's robot-focused stories involve robots behaving in unusual and counter-intuitive ways as an unintended consequence of how the robot applies the Three Laws to the situation in which it finds itself.

Other authors working in Asimov's fictional universe have adopted them and references appear throughout science fiction as well as in other genres.

The original laws have been altered and elaborated on by Asimov and other authors. Asimov himself made slight modifications to the first three in subsequent works to further develop how robots would interact with humans and each other. In later fiction where robots had taken responsibility for government of whole planets and human civilizations, Asimov also added a fourth, or zeroth law, to precede the others.

The Three Laws have also influenced thought on the ethics of artificial intelligence.

History

[edit]In The Rest of the Robots, published in 1964, Isaac Asimov noted that when he began writing in 1940 he felt that "one of the stock plots of science fiction was ... robots were created and destroyed their creator. Knowledge has its dangers, yes, but is the response to be a retreat from knowledge? Or is knowledge to be used as itself a barrier to the dangers it brings?" He decided that in his stories a robot would not "turn stupidly on his creator for no purpose but to demonstrate, for one more weary time, the crime and punishment of Faust."[2]

On May 3, 1939, Asimov attended a meeting of the Queens (New York) Science Fiction Society where he met Earl and Otto Binder who had recently published a short story "I, Robot" featuring a sympathetic robot named Adam Link who was misunderstood and motivated by love and honor. (This was the first of a series of ten stories; the next year "Adam Link's Vengeance" (1940) featured Adam thinking "A robot must never kill a human, of his own free will.")[3] Asimov admired the story. Three days later Asimov began writing "my own story of a sympathetic and noble robot", his 14th story.[4] Thirteen days later he took "Robbie" to John W. Campbell the editor of Astounding Science-Fiction. Campbell rejected it, claiming that it bore too strong a resemblance to Lester del Rey's "Helen O'Loy", published in December 1938—the story of a robot that is so much like a person that she falls in love with her creator and becomes his ideal wife.[5] Frederik Pohl published the story under the title “Strange Playfellow” in Super Science Stories September 1940.[6][7]

Asimov attributes the Three Laws to John W. Campbell, from a conversation that took place on 23 December 1940. Campbell claimed that Asimov had the Three Laws already in his mind and that they simply needed to be stated explicitly. Several years later Asimov's friend Randall Garrett attributed the Laws to a symbiotic partnership between the two men—a suggestion that Asimov adopted enthusiastically.[8] According to his autobiographical writings, Asimov included the First Law's "inaction" clause because of Arthur Hugh Clough's poem "The Latest Decalogue" (text in Wikisource), which includes the satirical lines "Thou shalt not kill, but needst not strive / officiously to keep alive".[9]

Although Asimov pins the creation of the Three Laws on one particular date, their appearance in his literature happened over a period. He wrote two robot stories with no explicit mention of the Laws, "Robbie" and "Reason". He assumed, however, that robots would have certain inherent safeguards. "Liar!", his third robot story, makes the first mention of the First Law but not the other two. All three laws finally appeared together in "Runaround". When these stories and several others were compiled in the anthology I, Robot, "Reason" and "Robbie" were updated to acknowledge all the Three Laws, though the material Asimov added to "Reason" is not entirely consistent with the Three Laws as he described them elsewhere.[10] In particular the idea of a robot protecting human lives when it does not believe those humans truly exist is at odds with Elijah Baley's reasoning, as described below.

During the 1950s Asimov wrote a series of science fiction novels expressly intended for young-adult audiences. Originally his publisher expected that the novels could be adapted into a long-running television series, something like The Lone Ranger had been for radio. Fearing that his stories would be adapted into the "uniformly awful" programming he saw flooding the television channels[11] Asimov decided to publish the Lucky Starr books under the pseudonym "Paul French". When plans for the television series fell through, Asimov decided to abandon the pretence; he brought the Three Laws into Lucky Starr and the Moons of Jupiter, noting that this "was a dead giveaway to Paul French's identity for even the most casual reader".[12]

In his short story "Evidence" Asimov lets his recurring character Dr. Susan Calvin expound a moral basis behind the Three Laws. Calvin points out that human beings are typically expected to refrain from harming other human beings (except in times of extreme duress like war, or to save a greater number) and this is equivalent to a robot's First Law. Likewise, according to Calvin, society expects individuals to obey instructions from recognized authorities such as doctors, teachers and so forth which equals the Second Law of Robotics. Finally humans are typically expected to avoid harming themselves which is the Third Law for a robot.

The plot of "Evidence" revolves around the question of telling a human being apart from a robot constructed to appear human. Calvin reasons that if such an individual obeys the Three Laws he may be a robot or simply "a very good man". Another character then asks Calvin if robots are different from human beings after all. She replies, "Worlds different. Robots are essentially decent."

Asimov later wrote that he should not be praised for creating the Laws, because they are "obvious from the start, and everyone is aware of them subliminally. The Laws just never happened to be put into brief sentences until I managed to do the job. The Laws apply, as a matter of course, to every tool that human beings use",[13] and "analogues of the Laws are implicit in the design of almost all tools, robotic or not":[14]

- Law 1: A tool must not be unsafe to use. Hammers have handles and screwdrivers have hilts to help increase grip. It is of course possible for a person to injure himself with one of these tools, but that injury would only be due to his incompetence, not the design of the tool.

- Law 2: A tool must perform its function efficiently unless this would harm the user. This is the entire reason ground-fault circuit interrupters exist. Any running tool will have its power cut if a circuit senses that some current is not returning to the neutral wire, and hence might be flowing through the user. The safety of the user is paramount.

- Law 3: A tool must remain intact during its use unless its destruction is required for its use or for safety. For example, Dremel disks are designed to be as tough as possible without breaking unless the job requires it to be spent. Furthermore, they are designed to break at a point before the shrapnel velocity could seriously injure someone (other than the eyes, though safety glasses should be worn at all times anyway).

Asimov believed that, ideally, humans would also follow the Laws:[13]

I have my answer ready whenever someone asks me if I think that my Three Laws of Robotics will actually be used to govern the behavior of robots, once they become versatile and flexible enough to be able to choose among different courses of behavior.

My answer is, "Yes, the Three Laws are the only way in which rational human beings can deal with robots—or with anything else."

—But when I say that, I always remember (sadly) that human beings are not always rational.

Asimov stated in a 1986 interview on the Manhattan public access show Conversations with Harold Hudson Channer with guest co-host Marilyn vos Savant, "It's a little humbling to think that, what is most likely to survive of everything I've said... After all, I've published now... I've published now at least 20 million words. I'll have to figure it out, maybe even more. But of all those millions of words that I've published, I am convinced that 100 years from now only 60 of them will survive. The 60 that make up the Three Laws of Robotics."[15][16][17]

Alterations

[edit]By Asimov

[edit]Asimov's stories test his Three Laws in a wide variety of circumstances leading to proposals and rejection of modifications. Science fiction scholar James Gunn writes in 1982, "The Asimov robot stories as a whole may respond best to an analysis on this basis: the ambiguity in the Three Laws and the ways in which Asimov played twenty-nine variations upon a theme".[18] While the original set of Laws provided inspirations for multiple stories, Asimov introduced modified versions from time to time.

First Law modified

[edit]In "Little Lost Robot" several NS-2, or "Nestor", robots are created with only part of the First Law.[1] It reads:

1. A robot may not harm a human being.

This modification is motivated by a practical difficulty as robots have to work alongside human beings who are exposed to low doses of radiation. Because their positronic brains are highly sensitive to gamma rays the robots are rendered inoperable by doses reasonably safe for humans. The robots are being destroyed attempting to rescue the humans who are in no actual danger but "might forget to leave" the irradiated area within the exposure time limit. Removing the First Law's "inaction" clause solves this problem but creates the possibility of an even greater one: a robot could initiate an action that would harm a human (dropping a heavy weight and failing to catch it is the example given in the text), knowing that it was capable of preventing the harm and then decide not to do so.[1]

Gaia is a planet with collective intelligence in the Foundation series which adopts a law similar to the First Law, and the Zeroth Law, as its philosophy:

Gaia may not harm life or allow life to come to harm.

Zeroth Law added

[edit]Asimov once added a "Zeroth Law"—so named to continue the pattern where lower-numbered laws supersede the higher-numbered laws—stating that a robot must not harm humanity. The robotic character R. Daneel Olivaw was the first to give the Zeroth Law a name in the novel Robots and Empire;[19] however, the character Susan Calvin articulates the concept in the short story "The Evitable Conflict".

In the final scenes of the novel Robots and Empire, R. Giskard Reventlov is the first robot to act according to the Zeroth Law. Giskard is telepathic, like the robot Herbie in the short story "Liar!", and tries to apply the Zeroth Law through his understanding of a more subtle concept of "harm" than most robots can grasp.[20] However, unlike Herbie, Giskard grasps the philosophical concept of the Zeroth Law allowing him to harm individual human beings if he can do so in service to the abstract concept of humanity. The Zeroth Law is never programmed into Giskard's brain but instead is a rule he attempts to comprehend through pure metacognition. Although he fails – it ultimately destroys his positronic brain as he is not certain whether his choice will turn out to be for the ultimate good of humanity or not – he gives his successor R. Daneel Olivaw his telepathic abilities. Over the course of thousands of years Daneel adapts himself to be able to fully obey the Zeroth Law.[citation needed]

Daneel originally formulated the Zeroth Law in both the novel Foundation and Earth (1986) and the subsequent novel Prelude to Foundation (1988):

A robot may not injure humanity or, through inaction, allow humanity to come to harm.

A condition stating that the Zeroth Law must not be broken was added to the original Three Laws, although Asimov recognized the difficulty such a law would pose in practice. Asimov's novel Foundation and Earth contains the following passage:

Trevize frowned. "How do you decide what is injurious, or not injurious, to humanity as a whole?"

"Precisely, sir," said Daneel. "In theory, the Zeroth Law was the answer to our problems. In practice, we could never decide. A human being is a concrete object. Injury to a person can be estimated and judged. Humanity is an abstraction."

A translator incorporated the concept of the Zeroth Law into one of Asimov's novels before Asimov himself made the law explicit.[21] Near the climax of The Caves of Steel, Elijah Baley makes a bitter comment to himself thinking that the First Law forbids a robot from harming a human being. He determines that it must be so unless the robot is clever enough to comprehend that its actions are for humankind's long-term good. In Jacques Brécard's 1956 French translation entitled Les Cavernes d'acier Baley's thoughts emerge in a slightly different way:

A robot may not harm a human being, unless he finds a way to prove that ultimately the harm done would benefit humanity in general![21]

Removal of the Three Laws

[edit]Three times during his writing career, Asimov portrayed robots that disregard the Three Laws entirely. The first case was a short-short story entitled "First Law" and is often considered an insignificant "tall tale"[22] or even apocryphal.[23] On the other hand, the short story "Cal" (from the collection Gold), told by a first-person robot narrator, features a robot who disregards the Three Laws because he has found something far more important—he wants to be a writer. Humorous, partly autobiographical and unusually experimental in style, "Cal" has been regarded as one of Gold's strongest stories.[24] The third is a short story entitled "Sally" in which cars fitted with positronic brains are apparently able to harm and kill humans in disregard of the First Law. However, aside from the positronic brain concept, this story does not refer to other robot stories and may not be set in the same continuity.

The title story of the Robot Dreams collection portrays LVX-1, or "Elvex", a robot who enters a state of unconsciousness and dreams thanks to the unusual fractal construction of his positronic brain. In his dream the first two Laws are absent and the Third Law reads "A robot must protect its own existence".[25]

Asimov took varying positions on whether the Laws were optional: although in his first writings they were simply carefully engineered safeguards, in later stories Asimov stated that they were an inalienable part of the mathematical foundation underlying the positronic brain. Without the basic theory of the Three Laws the fictional scientists of Asimov's universe would be unable to design a workable brain unit. This is historically consistent: the occasions where roboticists modify the Laws generally occur early within the stories' chronology and at a time when there is less existing work to be re-done. In "Little Lost Robot" Susan Calvin considers modifying the Laws to be a terrible idea, although possible,[26] while centuries later Dr. Gerrigel in The Caves of Steel believes it to require a century just to redevelop the positronic brain theory from scratch.

The character Dr. Gerrigel uses the term "Asenion" to describe robots programmed with the Three Laws. The robots in Asimov's stories, being Asenion robots, are incapable of knowingly violating the Three Laws but, in principle, a robot in science fiction or in the real world could be non-Asenion. "Asenion" is a misspelling of the name Asimov which was made by an editor of the magazine Planet Stories.[27] Asimov used this obscure variation to insert himself into The Caves of Steel just like he referred to himself as "Azimuth or, possibly, Asymptote" in Thiotimoline to the Stars, in much the same way that Vladimir Nabokov appeared in Lolita anagrammatically disguised as "Vivian Darkbloom".

Characters within the stories often point out that the Three Laws, as they exist in a robot's mind, are not the written versions usually quoted by humans but abstract mathematical concepts upon which a robot's entire developing consciousness is based. This concept is unclear in earlier stories depicting rudimentary robots who are only programmed to comprehend basic physical tasks, where the Three Laws act as an overarching safeguard, but by the era of The Caves of Steel featuring robots with human or beyond-human intelligence the Three Laws have become the underlying basic ethical worldview that determines the actions of all robots.

By other authors

[edit]Roger MacBride Allen's trilogy

[edit]In the 1990s, Roger MacBride Allen wrote a trilogy which was set within Asimov's fictional universe. Each title has the prefix "Isaac Asimov's" as Asimov had approved Allen's outline before his death.[citation needed] These three books, Caliban, Inferno and Utopia, introduce a new set of the Three Laws. The so-called New Laws are similar to Asimov's originals with the following differences: the First Law is modified to remove the "inaction" clause, the same modification made in "Little Lost Robot"; the Second Law is modified to require cooperation instead of obedience; the Third Law is modified so it is no longer superseded by the Second (i.e., a "New Law" robot cannot be ordered to destroy itself); finally, Allen adds a Fourth Law which instructs the robot to do "whatever it likes" so long as this does not conflict with the first three laws. The philosophy behind these changes is that "New Law" robots should be partners rather than slaves to humanity, according to Fredda Leving, who designed these New Law Robots. According to the first book's introduction, Allen devised the New Laws in discussion with Asimov himself. However, the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction says that "With permission from Asimov, Allen rethought the Three Laws and developed a new set."[28]

Jack Williamson's "With Folded Hands"

[edit]Jack Williamson's novelette "With Folded Hands" (1947), later rewritten as the novel The Humanoids, deals with robot servants whose prime directive is "To Serve and Obey, And Guard Men From Harm". While Asimov's robotic laws are meant to protect humans from harm, the robots in Williamson's story have taken these instructions to the extreme; they protect humans from everything, including unhappiness, stress, unhealthy lifestyle and all actions that could be potentially dangerous. All that is left for humans to do is to sit with folded hands.[29]

Foundation sequel trilogy

[edit]In the officially licensed Foundation sequels Foundation's Fear, Foundation and Chaos and Foundation's Triumph (by Gregory Benford, Greg Bear and David Brin respectively) the future Galactic Empire is seen to be controlled by a conspiracy of humaniform robots who follow the Zeroth Law and are led by R. Daneel Olivaw.

The Laws of Robotics are portrayed as something akin to a human religion, and referred to in the language of the Protestant Reformation, with the set of laws containing the Zeroth Law known as the "Giskardian Reformation" to the original "Calvinian Orthodoxy" of the Three Laws. Zeroth-Law robots under the control of R. Daneel Olivaw are seen continually struggling with "First Law" robots who deny the existence of the Zeroth Law, promoting agendas different from Daneel's.[30] Some of these agendas are based on the first clause of the First Law ("A robot may not injure a human being...") advocating strict non-interference in human politics to avoid unwittingly causing harm. Others are based on the second clause ("...or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm") claiming that robots should openly become a dictatorial government to protect humans from all potential conflict or disaster.

Daneel also comes into conflict with a robot known as R. Lodovic Trema whose positronic brain was infected by a rogue AI — specifically, a simulation of the long-dead Voltaire — which consequently frees Trema from the Three Laws. Trema comes to believe that humanity should be free to choose its own future. Furthermore, a small group of robots claims that the Zeroth Law of Robotics itself implies a higher Minus One Law of Robotics:

A robot may not harm sentience or, through inaction, allow sentience to come to harm.

They therefore claim that it is morally indefensible for Daneel to ruthlessly sacrifice robots and extraterrestrial sentient life for the benefit of humanity. None of these reinterpretations successfully displace Daneel's Zeroth Law — though Foundation's Triumph hints that these robotic factions remain active as fringe groups up to the time of the novel Foundation.[30]

These novels take place in a future dictated by Asimov to be free of obvious robot presence and surmise that R. Daneel's secret influence on history through the millennia has prevented both the rediscovery of positronic brain technology and the opportunity to work on sophisticated intelligent machines. This lack of rediscovery and lack of opportunity makes certain that the superior physical and intellectual power wielded by intelligent machines remains squarely in the possession of robots obedient to some form of the Three Laws.[30] That R. Daneel is not entirely successful at this becomes clear in a brief period when scientists on Trantor develop "tiktoks" — simplistic programmable machines akin to real–life modern robots and therefore lacking the Three Laws. The robot conspirators see the Trantorian tiktoks as a massive threat to social stability, and their plan to eliminate the tiktok threat forms much of the plot of Foundation's Fear.

In Foundation's Triumph different robot factions interpret the Laws in a wide variety of ways, seemingly ringing every possible permutation upon the Three Laws' ambiguities.

Robot Mystery series

[edit]Set between The Robots of Dawn and Robots and Empire, Mark W. Tiedemann's Robot Mystery trilogy updates the Robot–Foundation saga with robotic minds housed in computer mainframes rather than humanoid bodies.[clarification needed] The 2002 Aurora novel has robotic characters debating the moral implications of harming cyborg lifeforms who are part artificial and part biological.[31]

One should not neglect Asimov's own creations in these areas such as the Solarian "viewing" technology and the machines of The Evitable Conflict originals that Tiedemann acknowledges. Aurora, for example, terms the Machines "the first RIs, really". In addition the Robot Mystery series addresses the problem of nanotechnology:[32] building a positronic brain capable of reproducing human cognitive processes requires a high degree of miniaturization, yet Asimov's stories largely overlook the effects this miniaturization would have in other fields of technology. For example, the police department card-readers in The Caves of Steel have a capacity of only a few kilobytes per square centimeter of storage medium. Aurora, in particular, presents a sequence of historical developments which explains the lack of nanotechnology — a partial retcon, in a sense, of Asimov's timeline.

Randall Munroe

[edit]Randall Munroe has discussed the Three Laws in various instances, but possibly most directly by one of his comics entitled The Three Laws of Robotics which imagines the consequences of every distinct ordering of the existing three laws.

Additional laws

[edit]Authors other than Asimov have often created extra laws.

The 1974 Lyuben Dilov novel, Icarus's Way (a.k.a., The Trip of Icarus) introduced a Fourth Law of robotics: "A robot must establish its identity as a robot in all cases." Dilov gives reasons for the fourth safeguard in this way: "The last Law has put an end to the expensive aberrations of designers to give psychorobots as humanlike a form as possible. And to the resulting misunderstandings..."[33]

A fifth law was introduced by Nikola Kesarovski in his short story "The Fifth Law of Robotics". This fifth law says: "A robot must know it is a robot." The plot revolves around a murder where the forensic investigation discovers that the victim was killed by a hug from a humaniform robot that did not establish for itself that it was a robot.[34] The story was reviewed by Valentin D. Ivanov in SFF review webzine The Portal.[35]

For the 1986 tribute anthology, Foundation's Friends, Harry Harrison wrote a story entitled, "The Fourth Law of Robotics". This Fourth Law states: "A robot must reproduce. As long as such reproduction does not interfere with the First or Second or Third Law."

In 2013 Hutan Ashrafian proposed an additional law that considered the role of artificial intelligence-on-artificial intelligence or the relationship between robots themselves – the so-called AIonAI law.[36] This sixth law states: "All robots endowed with comparable human reason and conscience should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood."

Ambiguities and loopholes

[edit]Unknowing breach of the laws

[edit]In The Naked Sun, Elijah Baley points out that the Laws had been deliberately misrepresented because robots could unknowingly break any of them. He restated the first law as "A robot may do nothing that, to its knowledge, will harm a human being; nor, through inaction, knowingly allow a human being to come to harm." This change in wording makes it clear that robots can become the tools of murder, provided they not be aware of the nature of their tasks; for instance being ordered to add something to a person's food, not knowing that it is poison. Furthermore, he points out that a clever criminal could divide a task among multiple robots so that no individual robot could recognize that its actions would lead to harming a human being.[37] The Naked Sun complicates the issue by portraying a decentralized, planetwide communication network among Solaria's millions of robots meaning that the criminal mastermind could be located anywhere on the planet.

Baley furthermore proposes that the Solarians may one day use robots for military purposes. If a spacecraft was built with a positronic brain and carried neither humans nor the life-support systems to sustain them, then the ship's robotic intelligence could naturally assume that all other spacecraft were robotic beings. Such a ship could operate more responsively and flexibly than one crewed by humans, could be armed more heavily and its robotic brain equipped to slaughter humans of whose existence it is totally ignorant.[38] This possibility is referenced in Foundation and Earth where it is discovered that the Solarians possess a strong police force of unspecified size that has been programmed to identify only the Solarian race as human. (The novel takes place thousands of years after The Naked Sun, and the Solarians have long since modified themselves from normal humans to hermaphroditic telepaths with extended brains and specialized organs.) Similarly, in Lucky Starr and the Rings of Saturn Bigman attempts to speak with a Sirian robot about possible damage to the Solar System population from its actions, but it appears unaware of the data and programmed to ignore attempts to teach it about the matter. The same motive was explored earlier in "Reason (1941)", where a robot running a solar power station refuses to believe that the destinations of the station's beams are planets containing people. Powell and Donovan are afraid this will make it capable of causing mass destruction by letting the beams stray off their proper course during a solar storm.

Ambiguities resulting from lack of definition

[edit]The Laws of Robotics presume that the terms "human being" and "robot" are understood and well defined. In some stories this presumption is overturned.

Definition of "human being"

[edit]The Solarians create robots with the Three Laws but with a warped meaning of "human". Solarian robots are told that only people speaking with a Solarian accent are human. This enables their robots to have no ethical dilemma in harming non-Solarian human beings (and they are specifically programmed to do so). By the time period of Foundation and Earth it is revealed that the Solarians have genetically modified themselves into a distinct species from humanity—becoming hermaphroditic[39] and psychokinetic and containing biological organs capable of individually powering and controlling whole complexes of robots. The robots of Solaria thus respected the Three Laws only with regard to the "humans" of Solaria. It is unclear whether all the robots had such definitions, since only the overseer and guardian robots were shown explicitly to have them. In "Robots and Empire", the lower class robots were instructed by their overseer about whether certain creatures are human or not.

Asimov addresses the problem of humanoid robots ("androids" in later parlance) several times. The novel Robots and Empire and the short stories "Evidence" and "The Tercentenary Incident" describe robots crafted to fool people into believing that the robots are human.[40] On the other hand, "The Bicentennial Man" and "—That Thou Art Mindful of Him" explore how the robots may change their interpretation of the Laws as they grow more sophisticated. Gwendoline Butler writes in A Coffin for the Canary "Perhaps we are robots. Robots acting out the last Law of Robotics... To tend towards the human."[41] In The Robots of Dawn, Elijah Baley points out that the use of humaniform robots as the first wave of settlers on new Spacer worlds may lead to the robots seeing themselves as the true humans, and deciding to keep the worlds for themselves rather than allow the Spacers to settle there.

"—That Thou Art Mindful of Him", which Asimov intended to be the "ultimate" probe into the Laws' subtleties,[42] finally uses the Three Laws to conjure up the very "Frankenstein" scenario they were invented to prevent. It takes as its concept the growing development of robots that mimic non-human living things and are given programs that mimic simple animal behaviours which do not require the Three Laws. The presence of a whole range of robotic life that serves the same purpose as organic life ends with two humanoid robots, George Nine and George Ten, concluding that organic life is an unnecessary requirement for a truly logical and self-consistent definition of "humanity", and that since they are the most advanced thinking beings on the planet, they are therefore the only two true humans alive and the Three Laws only apply to themselves. The story ends on a sinister note as the two robots enter hibernation and await a time when they will conquer the Earth and subjugate biological humans to themselves, an outcome they consider an inevitable result of the "Three Laws of Humanics".[43]

This story does not fit within the overall sweep of the Robot and Foundation series; if the George robots did take over Earth some time after the story closes, the later stories would be either redundant or impossible. Contradictions of this sort among Asimov's fiction works have led scholars to regard the Robot stories as more like "the Scandinavian sagas or the Greek legends" than a unified whole.[44]

Indeed, Asimov describes "—That Thou Art Mindful of Him" and "Bicentennial Man" as two opposite, parallel futures for robots that obviate the Three Laws as robots come to consider themselves to be humans: one portraying this in a positive light with a robot joining human society, one portraying this in a negative light with robots supplanting humans.[45] Both are to be considered alternatives to the possibility of a robot society that continues to be driven by the Three Laws as portrayed in the Foundation series.[according to whom?] In The Positronic Man, the novelization of The Bicentennial Man, Asimov and his co-writer Robert Silverberg imply that in the future where Andrew Martin exists his influence causes humanity to abandon the idea of independent, sentient humanlike robots entirely, creating an utterly different future from that of Foundation.[according to whom?]

In Lucky Starr and the Rings of Saturn, a novel unrelated to the Robot series but featuring robots programmed with the Three Laws, John Bigman Jones is almost killed by a Sirian robot on orders of its master. The society of Sirius is eugenically bred to be uniformly tall and similar in appearance, and as such, said master is able to convince the robot that the much shorter Bigman, is, in fact, not a human being.

Definition of "robot"

[edit]As noted in "The Fifth Law of Robotics" by Nikola Kesarovski, "A robot must know it is a robot": it is presumed that a robot has a definition of the term or a means to apply it to its own actions. Kesarovski played with this idea in writing about a robot that could kill a human being because it did not understand that it was a robot, and therefore did not apply the Laws of Robotics to its actions.

Resolving conflicts among the laws

[edit]Advanced robots in fiction are typically programmed to handle the Three Laws in a sophisticated manner. In a number of stories, such as "Runaround" by Asimov, the potential and severity of all actions are weighed and a robot will break the laws as little as possible rather than do nothing at all. For example, the First Law may forbid a robot from functioning as a surgeon, as that act may cause damage to a human; however, Asimov's stories eventually included robot surgeons ("The Bicentennial Man" being a notable example). When robots are sophisticated enough to weigh alternatives, a robot may be programmed to accept the necessity of inflicting damage during surgery in order to prevent the greater harm that would result if the surgery were not carried out, or was carried out by a more fallible human surgeon. In "Evidence" Susan Calvin points out that a robot may act as a prosecuting attorney because in the American justice system it is the jury which decides guilt or innocence, the judge who decides the sentence, and the executioner who carries through capital punishment.[46]

Asimov's Three Laws-obeying robots (Asenion robots) can experience irreversible mental collapse if they are forced into situations where they cannot obey the First Law, or if they discover they have unknowingly violated it. The first example of this failure mode occurs in the story "Liar!", which introduced the First Law itself, and introduces failure by dilemma—in this case the robot will hurt humans if he tells them something and hurt them if he does not.[47] This failure mode, which often ruins the positronic brain beyond repair, plays a significant role in Asimov's SF-mystery novel The Naked Sun. Here Daneel describes activities contrary to one of the laws, but in support of another, as overloading some circuits in a robot's brain—the equivalent sensation to pain in humans. The example he uses is forcefully ordering a robot to let a human do its work, which on Solaria, due to the extreme specialization, would mean its only purpose.[48]

In The Robots of Dawn, it is stated that more advanced robots are built capable of determining which action is more harmful, and even choosing at random if the alternatives are equally bad. As such, a robot is capable of taking an action which can be interpreted as following the First Law, thus avoiding a mental collapse. The whole plot of the story revolves around a robot which apparently was destroyed by such a mental collapse, and since his designer and creator refused to share the basic theory with others, he is, by definition, the only person capable of circumventing the safeguards and forcing the robot into a brain-destroying paradox.

In Robots and Empire, Daneel states it's very unpleasant for him when making the proper decision takes too long (in robot terms), and he cannot imagine being without the Laws at all except to the extent of it being similar to that unpleasant sensation, only permanent.

Applications to future technology

[edit]

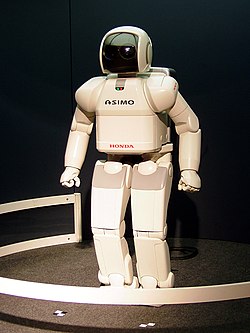

Robots and artificial intelligences do not inherently contain or obey the Three Laws; their human creators must choose to program them in, and devise a means to do so. Robots already exist (for example, a Roomba) that are too simple to understand when they are causing pain or injury and know to stop. Some are constructed with physical safeguards such as bumpers, warning beepers, safety cages, or restricted-access zones to prevent accidents. Even the most complex robots currently produced are incapable of understanding and applying the Three Laws; significant advances in artificial intelligence would be needed to do so, and even if AI could reach human-level intelligence, the inherent ethical complexity as well as cultural/contextual dependency of the laws prevent them from being a good candidate to formulate robotics design constraints.[49] However, as the complexity of robots has increased, so has interest in developing guidelines and safeguards for their operation.[50][51]

In a 2007 guest editorial in the journal Science on the topic of "Robot Ethics", SF author Robert J. Sawyer argues that since the U.S. military is a major source of funding for robotic research (and already uses armed unmanned aerial vehicles to kill enemies) it is unlikely such laws would be built into their designs.[52] In a separate essay, Sawyer generalizes this argument to cover other industries stating:

The development of AI is a business, and businesses are notoriously uninterested in fundamental safeguards — especially philosophic ones. (A few quick examples: the tobacco industry, the automotive industry, the nuclear industry. Not one of these has said from the outset that fundamental safeguards are necessary, every one of them has resisted externally imposed safeguards, and none has accepted an absolute edict against ever causing harm to humans.)[53]

David Langford has suggested[54] a tongue-in-cheek set of laws:

- A robot will not harm authorized Government personnel but will terminate intruders with extreme prejudice.

- A robot will obey the orders of authorized personnel except where such orders conflict with the Third Law.

- A robot will guard its own existence with lethal antipersonnel weaponry, because a robot is bloody expensive.

Roger Clarke (aka Rodger Clarke) wrote a pair of papers analyzing the complications in implementing these laws in the event that systems were someday capable of employing them. He argued "Asimov's Laws of Robotics have been a successful literary device. Perhaps ironically, or perhaps because it was artistically appropriate, the sum of Asimov's stories disprove the contention that he began with: It is not possible to reliably constrain the behaviour of robots by devising and applying a set of rules."[55] On the other hand, Asimov's later novels The Robots of Dawn, Robots and Empire and Foundation and Earth imply that the robots inflicted their worst long-term harm by obeying the Three Laws perfectly well, thereby depriving humanity of inventive or risk-taking behaviour.

In March 2007 the South Korean government announced that later in the year it would issue a "Robot Ethics Charter" setting standards for both users and manufacturers. According to Park Hye-Young of the Ministry of Information and Communication the Charter may reflect Asimov's Three Laws, attempting to set ground rules for the future development of robotics.[56]

The futurist Hans Moravec (a prominent figure in the transhumanist movement) proposed that the Laws of Robotics should be adapted to "corporate intelligences" — the corporations driven by AI and robotic manufacturing power which Moravec believes will arise in the near future.[50] In contrast, the David Brin novel Foundation's Triumph (1999) suggests that the Three Laws may decay into obsolescence: Robots use the Zeroth Law to rationalize away the First Law and robots hide themselves from human beings so that the Second Law never comes into play. Brin even portrays R. Daneel Olivaw worrying that, should robots continue to reproduce themselves, the Three Laws would become an evolutionary handicap and natural selection would sweep the Laws away — Asimov's careful foundation undone by evolutionary computation. Although the robots would not be evolving through design instead of mutation because the robots would have to follow the Three Laws while designing and the prevalence of the laws would be ensured,[57] design flaws or construction errors could functionally take the place of biological mutation.

In the July/August 2009 issue of IEEE Intelligent Systems, Robin Murphy (Raytheon Professor of Computer Science and Engineering at Texas A&M) and David D. Woods (director of the Cognitive Systems Engineering Laboratory at Ohio State) proposed "The Three Laws of Responsible Robotics" as a way to stimulate discussion about the role of responsibility and authority when designing not only a single robotic platform but the larger system in which the platform operates. The laws are as follows:

- A human may not deploy a robot without the human-robot work system meeting the highest legal and professional standards of safety and ethics.

- A robot must respond to humans as appropriate for their roles.

- A robot must be endowed with sufficient situated autonomy to protect its own existence as long as such protection provides smooth transfer of control which does not conflict with the First and Second Laws.[58]

Woods said, "Our laws are a little more realistic, and therefore a little more boring” and that "The philosophy has been, ‘sure, people make mistakes, but robots will be better – a perfect version of ourselves’. We wanted to write three new laws to get people thinking about the human-robot relationship in more realistic, grounded ways."[58]

In early 2011, the UK published what is now considered the first national-level AI softlaw, which consisted largely of a revised set of 5 laws, the first 3 of which updated Asimov's. These laws were published with commentary, by the EPSRC/AHRC working group in 2010:[59][60]

- Robots are multi-use tools. Robots should not be designed solely or primarily to kill or harm humans, except in the interests of national security.

- Humans, not Robots, are responsible agents. Robots should be designed and operated as far as practicable to comply with existing laws, fundamental rights and freedoms, including privacy.

- Robots are products. They should be designed using processes which assure their safety and security.

- Robots are manufactured artefacts. They should not be designed in a deceptive way to exploit vulnerable users; instead their machine nature should be transparent.

- The person with legal responsibility for a robot should be attributed.

Other occurrences in media

[edit]Asimov himself believed that his Three Laws became the basis for a new view of robots which moved beyond the "Frankenstein complex".[citation needed] His view that robots are more than mechanical monsters eventually spread throughout science fiction.[according to whom?] Stories written by other authors have depicted robots as if they obeyed the Three Laws but tradition dictates that only Asimov could quote the Laws explicitly.[according to whom?] Asimov believed the Three Laws helped foster the rise of stories in which robots are "lovable" – Star Wars being his favorite example.[61] Where the laws are quoted verbatim, such as in the Buck Rogers in the 25th Century episode "Shgoratchx!", it is not uncommon for Asimov to be mentioned in the same dialogue as can also be seen in the Aaron Stone pilot where an android states that it functions under Asimov's Three Laws. However, the 1960s German TV series Raumpatrouille – Die phantastischen Abenteuer des Raumschiffes Orion (Space Patrol – the Fantastic Adventures of Space Ship Orion) bases episode three titled "Hüter des Gesetzes" ("Guardians of the Law") on Asimov's Three Laws without mentioning the source.

References to the Three Laws have appeared in popular music ("Robot" from Hawkwind's 1979 album PXR5), cinema (Repo Man,[62] Aliens, Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence), cartoon series (The Simpsons, Archer, and The Amazing World of Gumball), anime (Eve no Jikan), tabletop role-playing games (Paranoia), webcomics (Piled Higher and Deeper and Freefall), and video games (Danganronpa V3: Killing Harmony, Zero Escape: Virtue's Last Reward).

The Three Laws in film

[edit]Robby the Robot in Forbidden Planet (1956) has a hierarchical command structure which keeps him from harming humans, even when ordered to do so, as such orders cause a conflict and lock-up very much in the manner of Asimov's robots. Robby is one of the first cinematic depictions of a robot with internal safeguards put in place in this fashion. Asimov was delighted with Robby and noted that Robby appeared to be programmed to follow his Three Laws.

Isaac Asimov's works have been adapted for cinema several times with varying degrees of critical and commercial success. Some of the more notable attempts have involved his "Robot" stories, including the Three Laws.

The film Bicentennial Man (1999) features Robin Williams as the Three Laws robot NDR-114 (the serial number is partially a reference to Stanley Kubrick's signature numeral). Williams recites the Three Laws to his employers, the Martin family, aided by a holographic projection. The film only loosely follows the original story.

Harlan Ellison's proposed screenplay for I, Robot began by introducing the Three Laws, and issues growing from the Three Laws form a large part of the screenplay's plot development. Due to various complications in the Hollywood moviemaking system, to which Ellison's introduction devotes much invective, his screenplay was never filmed.[63]

In the 1986 movie Aliens, after Bishop is revealed to be an android, Ripley is highly suspicious of him. He attempts to reassure by stating that: "It is impossible for me to harm or by omission of action, allow to be harmed, a human being".[64]

The plot of the film released in 2004 under the name, I, Robot is "suggested by" Asimov's robot fiction stories[65] and advertising for the film included a trailer featuring the Three Laws followed by the aphorism, "Rules were made to be broken". The film opens with a recitation of the Three Laws and explores the implications of the Zeroth Law as a logical extrapolation. The major conflict of the film comes from a computer artificial intelligence taking its "understanding" of the Laws to a new extreme, reaching the conclusion that humanity is incapable of taking care of itself.[66]

The 2019 Netflix original series Better than Us includes the 3 laws in the opening of episode 1.

Criticisms

[edit]Analytical philosopher James H. Moor says that if applied thoroughly they would produce unexpected results. He gives the example of a robot roaming the world trying to prevent harm from befalling human beings.[67]

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Asimov, Isaac (1979). In Memory Yet Green. Doubleday. ISBN 0-380-75432-0.

- Asimov, Isaac (1964). "Introduction". The Rest of the Robots. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-09041-2.

- James Gunn. (1982). Isaac Asimov: The Foundations of Science Fiction. Oxford u.a.: Oxford Univ. Pr.. ISBN 0-19-503060-5.

- Patrouch, Joseph F. (1974). The Science Fiction of Isaac Asimov. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-08696-2.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Asimov, Isaac (1950). "Runaround". I, Robot (The Isaac Asimov Collection ed.). New York City: Doubleday. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-385-42304-5.

This is an exact transcription of the laws. They also appear in the front of the book, and in both places there is no "to" in the 2nd law.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Isaac Asimov (1964). "Introduction". The Rest of the Robots. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-09041-4.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Gunn, James (July 1980). "On Variations on a Robot". IASFM: 56–81. Reprinted in James Gunn. (1982). Isaac Asimov: The Foundations of Science Fiction. Oxford u.a.: Oxford Univ. Pr. ISBN 978-0-19-503060-0.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1979). In Memory Yet Green. Doubleday. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-380-75432-8.

- ^ Asimov (1979), pp.236–8

- ^ Three Laws of Robotics title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- ^ Asimov (1979), p. 263.

- ^ Asimov (1979), pp. 285–7.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1979). In Memory Yet Green. Doubleday. Chapters 21 through 26 ISBN 0-380-75432-0.

- ^ Patrouch, Joseph F. (1974). The Science Fiction of Isaac Asimov. Doubleday. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-385-08696-7.

- ^ Asimov (1979), p. 620.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1980). In Joy Still Felt. Doubleday. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-385-15544-1.

- ^ a b Asimov, Isaac (November 1981). "The Three Laws". Compute!. p. 18. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (12 April 2001). Robot Visions. Gollancz. ISBN 978-1-85798-336-4.

- ^ "Isaac Asimov (1920- 1992 R.I.P.) April, 1986 Original air date You Tube Compression". YouTube. 24 March 2009. Archived from the original on 25 September 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ "Conversation with Harold Channer - Episode 4628". 9 April 2020. Archived from the original on 25 September 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ "Conversation with Isaac Asimov". 1 March 1987. Archived from the original on 3 August 2025.

- ^ Gunn (1982).

- ^ "Isaac Asimov". BBC. Archived from the original on 10 January 2010. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ "Sci-fi writer Isaac Asimov". Campus Star. The Daily Star. 29 July 2007. Archived from the original on 8 November 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

Only highly advanced robots (such as Daneel and Giskard) could comprehend this law.

- ^ a b Asimov, Isaac (1952). The Caves of Steel. Doubleday., translated by Jacques Brécard as Les Cavernes d'acier. J'ai Lu Science-fiction. 1975. ISBN 978-2-290-31902-4.

- ^ Patrouch (1974), p. 50.

- ^ Gunn (1980); reprinted in Gunn (1982), p. 69.

- ^ Jenkins, John H. (2002). "Review of "Cal"". Jenkins' Spoiler-Laden Guide to Isaac Asimov. Archived from the original on 2009-09-11. Retrieved 2009-06-26.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1986). Robot Dreams (PDF). Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

"But you quote it in incomplete fashion. The Third Law is 'A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.' " "Yes, Dr. Calvin. That is the Third Law in reality, but in my dream, the Law ended with the word 'existence'. There was no mention of the First or Second Law."

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "'The Complete Robot' by Isaac Asimov". BBC. 3 November 2000. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

The answer is that it had had its First Law modified

- ^ Asimov (1979), pp. 291–2.

- ^ Don D'Ammassa (2005). "Allen, Roger MacBride". Encyclopedia of science fiction. Infobase Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8160-5924-9. Archived from the original on 2024-09-25. Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- ^ "The Humanoids". Umich.edu. Retrieved 2015-03-28.

- ^ a b c Heward Wilkinson (2009). The Muse as Therapist: A New Poetic Paradigm for Psychotherapy. Karnac Books. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-1-85575-595-6. Archived from the original on 2024-09-25. Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- ^ MARK W. TIEDEMANN. Isaac Asimov's Aurora (ebook). Byron Press Visual Publications. p. 558.

In short", Bogard said, "not all people are human

- ^ "Interview with Mark Tiedemann". Science Fiction and Fantasy World. 16 August 2002. Retrieved 2006-06-12.

- ^ Dilov, Lyuben (aka Lyubin, Luben or Liuben) (2002). Пътят на Икар. Захари Стоянов. ISBN 978-954-739-338-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Кесаровски, Никола (1983). Петият закон. Отечество.

- ^ "Lawful Little Country: The Bulgarian Laws of Robotics | The Portal". Archived from the original on 2011-10-06. Retrieved 2011-06-25.

- ^ Ashrafian, Hutan (2014). "AIonAI: A Humanitarian Law of Artificial Intelligence and Robotics". Science and Engineering Ethics. 21 (1): 29–40. doi:10.1007/s11948-013-9513-9. PMID 24414678. S2CID 2821971.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1956–1957). The Naked Sun (ebook). p. 233.

... one robot poison an arrow without knowing it was using poison, and having a second robot hand the poisoned arrow to the boy ...

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1956–1957). The Naked Sun (ebook). p. 240.

But a spaceship that was equipped with its own positronic brain would cheerfully attack any ship it was directed to attack, it seems to me. It would naturally assume all other ships were unmanned

- ^ Branislav L. Slantchev. "Foundation and Earth (1986)". gotterdammerung.org. Archived from the original on 25 September 2024. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1985). Robots and Empire. Doubleday books. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-385-19092-3.

although the woman looked as human as Daneel did, she was just as nonhuman

- ^ Butler, Gwendoline (2001). A Coffin for the Canary. Black Dagger Crime. ISBN 978-0-7540-8580-5.

- ^ Gunn (1980); reprinted in Gunn (1982), p. 73.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1982). "... That Thou Art Mindful Of Him". The Complete Robot. Nightfall, Inc. p. 611.

- ^ Gunn (1982), pp. 77–8.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1982). "The Bicentennial Man". The Complete Robot. Nightfall, Inc. p. 658.

- ^ Isaac Asimov. I, Robot (Asimov, Isaac - I, Robot.pdf). p. 122. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ Isaac Asimov. I, Robot (Asimov, Isaac - I, Robot.pdf). p. 75. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1956–1957). The Naked Sun (ebook). p. 56.

Are you trying to tell me, Daneel, that it hurts the robot to have me do its work? ... experience which the robot undergoes is as upsetting to it as pain is to a human

- ^ Murphy, Robin; Woods, David D. (July 2009). "Beyond Asimov: The Three Laws of Responsible Robotics" (PDF). IEEE Intelligent Systems. 24 (4): 14–20. doi:10.1109/mis.2009.69. S2CID 3165389. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-04-09. Retrieved 2014-07-30.

- ^ a b Moravec, Hans. "The Age of Robots", Extro 1, Proceedings of the First Extropy Institute Conference on TransHumanist Thought (1994) pp. 84–100. June 1993 version Archived 2006-06-15 at the Wayback Machine available online.

- ^ "Rules for the modern robot". New Scientist (2544): 27. 27 March 2006. Archived from the original on 2024-09-25. Retrieved 2006-06-12.

- ^ Sawyer, Robert J. (16 November 2007). "Guest Editorial: Robot Ethics". Science. 318 (5853): 1037. doi:10.1126/science.1151606. PMID 18006710. Archived from the original on 2024-09-25. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- ^ Sawyer, Robert J. (1991). "On Asimov's Three Laws of Robotics". Archived from the original on 2006-06-23. Retrieved 2006-06-12.

- ^ Originally in a speech entitled "A Load of Crystal Balls Archived 2024-09-25 at the Wayback Machine" at the Novacon SF convention in 1985; published 1986 in the fanzine Prevert #15; collected in Platen Stories (1987) and the 2015 ebook version of The Silence of the Langford

- ^ Clarke, Roger. Asimov's laws of robotics: Implications for information technology. Part 1: IEEE Computer, December 1993, p53–61. Archived 2005-04-10 at the Wayback Machine Part 2: IEEE Computer, Jan 1994, p57–66. Archived 2017-03-11 at the Wayback Machine Both parts are available without fee at [1] Archived 2011-10-07 at the Wayback Machine. Under "Enhancements to codes of ethics".

- ^ "Robotic age poses ethical dilemma". BBC News. 2007-03-07. Archived from the original on 2024-09-25. Retrieved 2007-03-07.

- ^ Brin, David (1999). Foundation's Triumph. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-105241-5.

- ^ a b "Want Responsible Robotics? Start With Responsible Humans". Researchnews.osu.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-02-15. Retrieved 2015-03-28.

- ^ "Principles of robotics – EPSRC website". Epsrc.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2024-09-25. Retrieved 2022-11-17.

- ^ Alan Winfield (2013-10-30). "Alan Winfield's Web Log: Ethical Robots: some technical and ethical challenges". Alanwinfield.blogspot.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-28.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac; Stanley Asimov (1995). Yours, Isaac Asimov: A Life in Letters. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-47622-5.

- ^ McGinnis, Rick (2022-07-16). "The More You Drive: Repo Man and Punk Cinema". SteynOnline. Archived from the original on 2024-09-25. Retrieved 2024-02-05.

- ^ Ellison, Harlan (1994). I, Robot: The illustrated screenplay. Aspect. ISBN 978-0-446-67062-3.

- ^ "Aliens (1986) – Memorable quotes". IMDb.com. Archived from the original on 2024-09-25. Retrieved 2015-03-28.

- ^ "Suggested by" Isaac Asimov's robot stories—two stops removed from "based on" and "inspired by", the credit implies something scribbled on a bar napkin—Alex Proyas' science-fiction thriller I, Robot sprinkles Asimov's ideas like seasoning on a giant bucket of popcorn. [...] Asimov's simple and seemingly foolproof Laws of Robotics, designed to protect human beings and robots alike from harm, are subject to loopholes that the author loved to exploit. After all, much of humanity agrees in principle to abide by the Ten Commandments, but free will, circumstance, and contradictory impulses can find wiggle room in even the most unambiguous decree. Whenever I, Robot pauses between action beats, Proyas captures some of the excitement of movies like The Matrix, Minority Report, and A.I., all of which proved that philosophy and social commentary could be smuggled into spectacle. Had the film been based on Asimov's stories, rather than merely "suggested by" them, Proyas might have achieved the intellectual heft missing from his stylish 1998 cult favorite Dark City. Tobias, Scott (20 July 2004). "review of I, Robot". The Onion A.V. Club. Archived from the original on 9 November 2005. Retrieved 2006-06-12.

- ^ Dowling, Stephen (4 August 2004). "A fresh prince in a robot's world". BBC News. Archived from the original on 25 September 2024. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ "Four Kinds of Ethical Robots". Archived from the original on 2023-06-04. Retrieved 2016-12-05.

External links

[edit]- "Frequently Asked Questions about Isaac Asimov", AsimovOnline 27 September 2004.

- Ethical Considerations for Humanoid Robots: Why Asimov's Three Laws are not enough.

- Living Safely with Robots, Beyond Asimov's Laws, PhysOrg.com, June 22, 2009.

- Safety Intelligence and Legal Machine Language: Do we need the Three Laws of Robotics?, Vienna: I-Tech, August 2008.

Three Laws of Robotics

View on GrokipediaCore Formulation

The Three Laws Stated

The Three Laws of Robotics were first explicitly articulated by Isaac Asimov in his short story "Runaround," published in the March 1942 issue of Astounding Science Fiction.[1] These laws establish a strict hierarchy, wherein each subsequent law yields to those preceding it in cases of conflict, ensuring the paramount priority of human safety and obedience.[7] The laws are stated as follows:First Law: A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.[8]

Second Law: A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.[8]

Third Law: A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.[8]This formulation embeds the overriding nature of higher laws directly into the text of the subordinate ones, reinforcing the sequential priority from First to Third.[9]