Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

History of robots

View on Wikipedia

The history of robots has its origins in the ancient world. During the Industrial Revolution, humans developed the structural engineering capability to control electricity so that machines could be powered with small motors. In the early 20th century, the notion of a humanoid machine was developed.

The first uses of modern robots were in factories as industrial robots. These industrial robots were fixed machines capable of manufacturing tasks which allowed production with less human work. Digitally programmed industrial robots with artificial intelligence have been built since the 2000s.

Early legends

[edit]

Concepts of artificial servants and companions date at least as far back as the ancient legends of Cadmus, who is said to have sown dragon teeth that turned into soldiers and Pygmalion whose statue of Galatea came to life. Many ancient mythologies included artificial people, such as the talking mechanical handmaidens (Ancient Greek: Κουραι Χρυσεαι (Kourai Khryseai); "Golden Maidens"[1]) built by the Greek god Hephaestus (Vulcan to the Romans) out of gold.[2]

The Buddhist scholar Daoxuan (596-667 AD) described humanoid automata crafted from metals that recite sacred texts in a cloister which housed a fabulous clock. The "precious metal-people" weeped when Buddha Shakyamuni died.[3] Humanoid automations also feature in the Epic of King Gesar, a Central Asian cultural hero.[4]

Early Chinese lore on the legendary carpenter Lu Ban and the philosopher Mozi described mechanical imitations of animals and demons.[5] The implications of humanoid automatons were discussed in Liezi (4th century CE), a compilation of Daoist texts which went on to become a classic. In chapter 5 King Mu of Zhou is on tour of the West and upon asking the craftsman Master Yan Shi "What can you do?" the royal court is presented with an artificial man. The automation was indistinguishable from a human and performed various tricks for the king and his entourage. But the king flew into a rage when apparently the automation started to flirt with the ladies in attendance and threatened the automation with execution. So the craftsman cut the automation open and revealed the inner workings of the artificial man. The king is fascinated and experiments with the functional interdependence of the automation by removing different organlike components. The king marveled "is it then possible for human skill to achieve as much as the Creator?" and confiscated the automation.[6] A similar tale can be found in the near contemporary Indian Buddhist Jataka tales, but here the intricacy of the automation does not match that of Master Yan.[4] Prior to the introduction of Buddhism in the Common Era, Chinese philosophers did not seriously consider the distinction between appearance and reality. The Liezi rebuts Buddhist philosophies and likens human creative powers to that of the Creator.[7]

The Indian Lokapannatti, a collection of cycles and lores produced in the 11th or 12th century AD,[8] tells the story of how an army of automated soldiers (bhuta vahana yanta or "Spirit movement machines") were crafted to protect the relics of Buddha in a secret stupa. The plans for making such humanoid automatons were stolen from the kingdom of Rome, a generic term for the Greco-Roman-Byzantine culture. According to the Lokapannatti, the Yavanas ("Greek-speakers") used the automatons to carry out trade and farming, but also captured and executed criminals. Roman automation makers who left the kingdom were pursued and killed by the automatons. According to the Lokapannatti, the emperor Asoka hears the story of the secret stupa and sets out to find it. Following a battle between the fierce warrior automatons, Asoka finds the long-lived engineer who had constructed the automatons and is shown how to dismantle and control them. Thus emperor Asoka manages to command a large army of automated warriors. This Indian tale reflects the fear of losing control of artificial beings, which has also been expressed in Greek myths about the dragon-teeth army.[9]

Inspired by European Christian legend, medieval Europeans devised brazen heads that could answer questions posed to them. Albertus Magnus was supposed to have constructed an entire android which could perform some domestic tasks, but it was destroyed by Albert's student Thomas Aquinas for disturbing his thought.[10] The most famous legend concerned a bronze head devised by Roger Bacon which was destroyed or scrapped after he missed its moment of operation.[10] Automata resembling humans or animals were popular in the imaginary worlds of medieval literature.[11][12]

Automata

[edit]In the 4th century BC the mathematician Archytas of Tarentum postulated a mechanical bird he called "The Pigeon", which was propelled by steam.[13] Taking up the earlier reference in Homer's Iliad, Aristotle speculated in his Politics (ca. 322 BC, book 1, part 4) that automata could someday bring about human equality by making possible the abolition of slavery:

There is only one condition in which we can imagine managers not needing subordinates, and masters not needing slaves. This condition would be that each instrument could do its own work, at the word of command or by intelligent anticipation, like the statues of Daedalus or the tripods made by Hephaestus, of which Homer relates that "Of their own motion they entered the conclave of Gods on Olympus", as if a shuttle should weave of itself, and a plectrum should do its own harp playing.

When the Greeks controlled Egypt, a succession of engineers who could construct automata established themselves in Alexandria. Starting with the polymath Ctesibius (285-222 BC), Alexandrian engineers left behind texts detailing workable automata powered by hydraulics or steam. Ctesibius built human-like automata, often these were used in religious ceremonies and the worship of deities. One of the last great Alexandrian engineers, Hero of Alexandria (10-70 CE) constructed an automata puppet theater, where the figurines and the stage sets moved by mechanical means. He described the construction of such automata in his treatise on pneumatics.[14] Alexandrian engineers constructed automata as reverence for humans' apparent command over nature and as tools for priests, but also started a tradition where automata were constructed for anyone who was wealthy enough and primarily for the entertainment of the rich.[15]

The manufacturing tradition of automata continued in the Greek world well into the Middle Ages. On his visit to Constantinople in 949 ambassador Liutprand of Cremona described automata in the emperor Theophilos' palace, including

"lions, made either of bronze or wood covered with gold, which struck the ground with their tails and roared with open mouth and quivering tongue," "a tree of gilded bronze, its branches filled with birds, likewise made of bronze gilded over, and these emitted cries appropriate to their species" and "the emperor's throne" itself, which "was made in such a cunning manner that at one moment it was down on the ground, while at another it rose higher and was to be seen up in the air."[16]

Similar automata in the throne room (singing birds, roaring and moving lions) were described by Luitprand's contemporary, the Byzantine emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus, in his book Περὶ τῆς Βασιλείου Τάξεως.

In China the Cosmic Engine, a 10-metre (33 ft) clock tower built by Su Song in Kaifeng, China, in 1088 CE, featured mechanical mannequins that chimed the hours, ringing gongs or bells among other devices.[17] Feats of automation continued into the Tang dynasty. Daifeng Ma built an automated dresser servant for the queen.[18] Ying Wenliang built an automata man that proposed toasts at banquets and a wooden woman automata that played the sheng. Among the best documented automata of ancient China are that of Han Zhile, a Japanese who moved to China in the early 9th century CE.[19]

Post-classical societies such as the Byzantines and Arabs continued the construction of automata. The Byzantines inherited the knowledge on automata from the Alexandrians and developed it further to build water clocks with gear mechanisms, such as for example described by Procopius about 510. It was in the medieval Arab world where more significant advances in the construction of automata would take place. Harun al-Rashid built water clocks with complicated hydraulic jacks and moving human figures. One such clock was gifted to Charlemagne, King of the Franks, in 807.[20] Arab engineers such as Banu Musa and Al-Jazari published treatise on hydraulics and further advanced the art of water clocks. Al-Jazari built automated moving peacocks driven by hydropower.[21] He invented a water wheels with cams on their axle used to operate automata.[22] One of al-Jazari's humanoid automata was a waitress that could serve water, tea or drinks. The drink was stored in a tank with a reservoir from where the drink drips into a bucket and, after seven minutes, into a cup, after which the waitress appears out of an automatic door serving the drink.[23] Al-Jazari invented a hand washing automaton incorporating a flush mechanism now used in modern flush toilets. It features a female humanoid automaton standing by a basin filled with water. When the user pulls the lever, the water drains and the female automaton refills the basin.[24] Furthermore, he created a robotic musical band.[25] According to Mark Rosheim, unlike Greek designs Arab automata worked with dramatic illusion and manipulated the human perception for practical application.[26]

The segmental gears described in The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices, published by Al-Jazari shortly before his death in 1206, appeared 100 years later in the most advanced European clocks. Al-Jazari also published instructions on the construction of humanoid automata.[27] The first water clocks modeled on Arabic designs were constructed in Europe about 1000 CE, possibly on the basis of the information that was transmitted during Muslim-Christian contact in Sicily and Spain. Among the first recorded European water clocks is that of Gerbert of Aurillac, built in 985 CE.[28] Hero's works on automata were translated into Latin amid the 12th century Renaissance. The early 13th-century artist-engineer Villard de Honnecourt sketched plans for several automata. At the end of the 13th century, Robert II, Count of Artois, built a pleasure garden at his castle at Hesdin that incorporated a number of robots, humanoid and animal.[29] Automated bellstrikers, called jacquemart, became popular in Europe in the 14th century alongside mechanical clocks.[28]

Among the first verifiable automation is a humanoid drawn by Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) in around 1495. Leonardo's notebooks, rediscovered in the 1950s, contain detailed drawings of a mechanical knight in armor which was able to sit up, wave its arms and move its head and jaw.[30] In the mid-1400s, Johannes Müller von Königsberg created an automaton eagle and fly made of iron; both could fly. John Dee is also known for creating a wooden beetle, capable of flying.[31]

The 17th-century thinker René Descartes believed that animals and humans were biological machines. On his last trip to Norway, he took with him a mechanical doll that looked like his dead daughter Francine.[32] In the 18th century the master toymaker Jacques de Vaucanson built for Louis XV an automated duck with hundreds of moving parts, which could eat and drink. Vaucanson subsequently built humanoid automatons, a drummer and fife player were noted for their anatomical similarity to real human beings.[33] Vaucanson's creation inspired European watchmakers to manufacture mechanical automata and it became fashionable among the European aristocracy to collect sophisticated mechanical devices for entertainment.[32] In 1747 Julien Offray de La Mettrie anonymously published L'homme machine (Man a Machine), in which he called Vaucanson a "new Prometheus" and mused "the human body is a watch, a large watch constructed with such skill and ingenuity".[34]

In the 1770s the Swiss Pierre Jaquet-Droz created moving automata that looked like children, which delighted Mary Shelley, who went on to write the 1818 novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. The ultimate attempt at automation was The Turk by Wolfgang von Kempelen, a seemingly sophisticated machine that could play chess against a human opponent and toured Europe. When the machine was brought to the new world, it prompted Edgar Allan Poe to pen an essay, in which he concluded that it was impossible for mechanical devices to reason or think.[32] However, The Mechanical Turk was later revealed to be an elaborate hoax: The machine concealed a human, who operated it from the inside.

In the 19th century the Japanese craftsman Hisashige Tanaka, known as "Japan's Edison", created an array of extremely complex mechanical toys, some of which could serve tea, fire arrows drawn from a quiver, or even paint a Japanese kanji character. The landmark text Karakuri Zui (Illustrated Machinery) was published in 1796.[35] In 1898 Nikola Tesla demonstrated his "teleautomaton", a prototype remote-controlled boat at Madison Square Garden as "an automaton which left to itself, will act as though possessed of reason and without any willful control from the outside." He defended his invention against critical reporters, arguing that it was not a "wireless torpedo", but instead, "the first of a race of robots, mechanical men which will do the laborious work of the human race."[36]

Modern history

[edit]

1900s

[edit]Starting in 1900, L. Frank Baum introduced contemporary technology into children's books in the Oz series. In The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900) Baum told the story of the cyborg Tin Woodman, a human woodcutter who had his limbs, head and body replaced by a tinsmith after his wicked axe had severed them. In Ozma of Oz (1907) Baum describes the copper clockwork man Tik-Tok, who needs to be continuously wound up and runs down at inopportune moments.[38]

In 1903, the Spanish engineer Leonardo Torres Quevedo introduced a radio based control system called the "Telekino" at the Paris Academy of Science.[39] It was intended as a way of testing a dirigible of his own design without risking human lives. Unlike other methods, which carried out 'on/off' actions, Torres established a system for controlling any mechanical or electrical device with different states of operation.[40] The transmitter was capable of sending a family of different codewords by means of a binary telegraph signal, and the receiver was able to set up a different state of operation in the device being used, depending on the codeword. The Telekino could execute 19 different commands. In 1905, Torres chose to conduct initial Telekino testing in an electrical three-wheeled land vehicle.[41] In 1906, in the presence of an audience which included the King of Spain, Torres demonstrated the invention in the Port of Bilbao, guiding a boat from the shore with people on board, which was controlled at a distance over 2 km.[42]

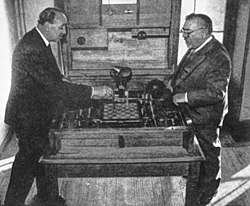

1910s

[edit]In 1912, Leonardo Torres Quevedo built the first truly autonomous machine capable of playing chess. As opposed to the human-operated The Turk and Ajeeb, El Ajedrecista (The Chessplayer) had a true integrated automation built to play chess without human guidance. It only played an endgame with three chess pieces, automatically moving a white king and a rook to checkmate the black king moved by a human opponent.[43][44] In 1951 El Ajedrecista defeats Savielly Tartakower at the Paris Cybernetic Conference, being the first Grandmaster to be defeated by a machine.[45] In his 1914 paper Essays on Automatics, Torres proposed a machine that makes "judgments" using sensors that capture information from the outside, parts that manipulate the outside world like arms, power sources such as batteries and air pressure, and most importantly, captured information and past information. It was defined as an organism that can control reactions in response to external information and adapt to changes in the environment to change its behavior.[46][47][48][49]

1920s

[edit]The term "robot" was first used in a play published by the Czech Karel Čapek in 1920. R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots) was a satire, robots were manufactured biological beings that performed all unpleasant manual labor.[50] According to Čapek, the word was created by his brother Josef from the Czech word robota 'corvée', or in Slovak 'work' or 'labor'.[51] (Karel Čapek was working on his play during his stay in Trenčianske Teplice in Slovakia where his father worked as a medical doctor.) The play R.U.R, replaced the popular use of the word "automaton".[52]

Westinghouse Electric Corporation built Televox in 1926; it was a cardboard cutout connected to various devices which users could turn on and off.[53] In 1927, Fritz Lang's Metropolis was released; the Maschinenmensch ("machine-human"), a gynoid humanoid robot, also called "Parody", "Futura", "Robotrix", or the "Maria impersonator" (played by German actress Brigitte Helm), was the first robot ever to be depicted on film.[54]

The most famous Japanese robotic automaton was presented to the public in 1927. The Gakutensoku was supposed to have a diplomatic role. Actuated by compressed air, it could write fluidly and raise its eyelids.[19] Many robots were constructed before the dawn of computer-controlled servomechanisms, for the public relations purposes of major firms. These were essentially machines that could perform a few stunts, like the automata of the 18th century. In 1928, one of the first humanoid robots was exhibited at the annual exhibition of the Model Engineers Society in London. Invented by W. H. Richards, the robot - named Eric - consisted of an aluminium suit of armour with eleven electromagnets and one motor powered by a 12-volt power source. The robot could move its hands and head and could be controlled by remote control or voice control.[55]

1930s

[edit]The earliest designs of industrial robots were put into production in the United States. These manipulators had joints modelled on human shoulder-arm-wrist kinetics to replicate human motions like pulling, pushing, pressing and lifting. Motions could be controlled through cam and switch programming. In 1938 Willard V. Pollard filed the first patent application for such an arm, the "Position Controlling Apparatus" with electronic controllers, pneumatic cylinder and motors that powered six axes of motion. But the large drum memory made programming time-consuming and difficult.[56]

In 1939, the humanoid robot known as Elektro appeared at the World's Fair.[57][58] Seven feet tall (2.1 m) and weighing 265 pounds (120 kg), it could walk by voice command, speak about 700 words (using a 78-rpm record player), smoke cigarettes, blow up balloons, and move its head and arms. The body consisted of a steel gear cam and motor skeleton covered by an aluminium skin.[59]

In 1939 Konrad Zuse constructed the first programmable electromechanical computer, laying the foundation for the construction of a humanoid machine that is now deemed a robot.[60] The practical application of binary logic to electric switches had been demonstrated by Claude Shannon, but his calculator was not programmable.[61]

1940s

[edit]In 1941 and 1942, Isaac Asimov formulated the Three Laws of Robotics, and in the process coined the word "robotics".[citation needed] In 1945 Vannevar Bush published As We May Think, an essay that investigated the potential of electronic data processing. He predicted the rise of computers, digital word processors, voice recognition and machine translation. He was later credited by Ted Nelson, the inventor of hypertext.[18]

In 1943 Arturo Rosenblueth, Norbert Wiener and Julian Bigelow adopted the human central nervous system as control paradigm for automatic weapons systems. In doing so they pioneered cybernetics (Greek for steersman) and modelled data processing on the assumption that an animal continually communicates its sensorial experience to its central nervous system as automatic and involuntary feedback, thus being able to regulate processes such as respiration, circulation and digestion.[62] Following the Second World War, at a 1946 conference on cybernetics, Warren McCulloch gathered a team of mathematicians, computer engineers, physiologists and psychologists to work on machine operation using biological systems as starting point. Following the publication of his book in 1948, Wiener's idea that inanimate systems could simulate biological and social systems through the use of sensors led to the adaption of cybernetic theories into industrial machines. But servo controllers proved inadequate in achieving the desired level of automation.[63]

The first electronic autonomous robots with complex behavior were created by William Grey Walter of the Burden Neurological Institute at Bristol, England in 1948 and 1949. He wanted to prove that rich connections between a small number of brain cells could give rise to very complex behaviors - essentially that the secret of how the brain worked lay in how it was wired up. His first robots, named Elmer and Elsie, were constructed between 1948 and 1949 and were often described as "tortoises" due to their shape and slow rate of movement. The three-wheeled tortoise robots were capable of phototaxis, by which they could find their way to a recharging station when they ran low on battery power.[citation needed]

Walter stressed the importance of using purely analogue electronics to simulate brain processes at a time when his contemporaries such as Alan Turing and John von Neumann were all turning towards a view of mental processes in terms of digital computation. Walter's work inspired subsequent generations of robotics researchers such as Rodney Brooks, Hans Moravec and Mark Tilden. Modern incarnations of Walter's "turtles" may be found in the form of BEAM robotics.[64]

In 1949 Tony Sale built a simple 6-foot (1.8 m) humanoid robot he named George, created from scrap metal from a grounded Wellington bomber. After being stored away in its inventor's shed, the robot was restored in 2010 and shown in an episode of Wallace & Gromit's World of Invention. After the reactivation, Tony Sale donated George to the National Museum of Computing, where it remains on display to the public.

1950s

[edit]

In 1951 Walter published the paper A Machine that learns, documenting how his more advanced mechanical robots acted as intelligent agent by demonstrating conditioned reflex learning.[18]

Unimate, the first digitally operated and programmable robot, was invented by George Devol in 1950 and "represents the foundation of the modern robotics industry."[65][66]

In Japan, robots became popular comic book characters. Robots became cultural icons and the Japanese government was spurred into funding research into robotics. Among the most iconic characters was the Astro Boy, who is taught human feelings such as love, courage and self-doubt. Culturally, robots in Japan became regarded as helpmates to their human counterparts.[67]

The introduction of transistors into computers in the mid-1950s reduced their size and increased performance. Therefore, computing and programming could be incorporated into a range of applications, including automation.[68] In 1959 researchers of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) demonstrated computer-assisted manufacturing.[69]

1960s

[edit]Devol sold the first Unimate to General Motors in 1960, and it was installed in 1961 in a plant in Ewing Township, New Jersey, to lift hot pieces of metal from a die casting machine and place them in cooling liquid.[70][71] "Without any fanfare, the world's first working robot joined the assembly line at the General Motors plant in Ewing Township in the spring of 1961... It was an automated die-casting mold that dropped red-hot door handles and other such car parts into pools of cooling liquid on a line that moved them along to workers for trimming and buffing." Devol's patent for the first digitally operated programmable robotic arm represents the foundation of the modern robotics industry.[72]

The Rancho Arm was developed as a robotic arm to help handicapped patients at the Rancho Los Amigos Hospital in Downey, California; this computer-controlled arm was bought by Stanford University in 1963.[73] In 1967 the first industrial robot was put to productive use in Japan. The Versatran robot had been developed by American Machine and Foundry. A year later a hydraulic robot design by Unimation was put into production by Kawasaki Heavy Industries.[74] Marvin Minsky created the Tentacle Arm in 1968; the arm was computer-controlled and its 12 joints were powered by hydraulics.[73] In 1969 Mechanical Engineering student Victor Scheinman created the Stanford Arm, recognized as the first electronic computer-controlled robotic arm because the Unimate's instructions were stored on a magnetic drum.[73]

In the late-1960s the Vietnam War became the testing ground for automated command technology and sensor networks.[75] In 1966 the McNamara Line was proposed with the aim of requiring virtually no ground forces. This sensor network of seismic and acoustic sensors, photoreconnaissance and sensor-triggered land mines was only partially implemented due to high cost.[76] The first mobile robot capable of reasoning about its surroundings, Shakey, was built in 1970 by the Stanford Research Institute (now SRI International). Shakey combined multiple sensor inputs, including TV cameras, laser rangefinders, and "bump sensors" to navigate.[73]

1970s

[edit]

In the early 1970s precision munitions and smart weapons were developed. Weapons became robotic by implementing terminal guidance. At the end of the Vietnam War the first laser-guided bombs were deployed, which could find their target by following a laser beam that was pointed at the target. During the 1972 Operation Linebacker laser-guided bombs proved effective, but still depended heavily on human operators. Fire-and-forget weapons were also first deployed in the closing Vietnam War, once launched no further attention or action was required from the operator.[76]

The development of humanoid robots was advanced considerably by Japanese robotics scientists in the 1970s.[77] Waseda University initiated the WABOT project in 1967, and in 1972 completed the WABOT-1, the world's first full-scale humanoid intelligent robot.[78] Its limb control system allowed it to walk with the lower limbs, and to grip and transport objects with hands, using tactile sensors. Its vision system allowed it to measure distances and directions to objects using external receptors, artificial eyes and ears. And its conversation system allowed it to communicate with a person in Japanese, with an artificial mouth. This made it the first android.[79][80]

Freddy and Freddy II were robots built at the University of Edinburgh School of Informatics by Pat Ambler, Robin Popplestone, Austin Tate, and Donald Mitchie, and were capable of assembling wooden blocks in a period of several hours.[81] German based company KUKA built the world's first industrial robot with six electromechanically driven axes, known as FAMULUS.[82]

In 1974, Michael J. Freeman created Leachim, a robot teacher who was programmed with the class curricular, as well as certain biographical information on the 40 students whom Leachim was programmed to teach.[83] Leachim had the ability to synthesize human speech.[84] Leachim was tested in a fourth grade classroom in the Bronx borough of New York City.[85]

In 1974, David Silver designed The Silver Arm, which was capable of fine movements replicating human hands. Feedback was provided by touch and pressure sensors and analyzed by a computer.[73] The SCARA, Selective Compliance Assembly Robot Arm, was created in 1978 as an efficient, 4-axis robotic arm. Best used for picking up parts and placing them in another location, the SCARA was introduced to assembly lines in 1981.[86]

The Stanford Cart successfully crossed a room full of chairs in 1979. It relied primarily on stereo vision to navigate and determine distances.[73] The Robotics Institute at Carnegie Mellon University was founded in 1979 by Raj Reddy.[87]

1980s

[edit]

Takeo Kanade created the first "direct-drive arm" in 1981. The first of its kind, the arm's motors were contained within the robot itself, eliminating long transmissions.[89]

In 1984 Wabot-2 was revealed; capable of playing the organ, Wabot-2 had 10 fingers and two feet. Wabot-2 was able to read a score of music and accompany a person.[90]

In 1986, Honda began its humanoid research and development program to create robots capable of interacting successfully with humans.[91] A hexapodal robot named Genghis was revealed by MIT in 1989. Genghis was famous for being made quickly and cheaply due to construction methods; Genghis used 4 microprocessors, 22 sensors, and 12 servo motors.[92] Rodney Brooks and Anita M. Flynn published "Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control: A Robot Invasion of The Solar System". The paper advocated creating smaller cheaper robots in greater numbers to increase production time and decrease the difficulty of launching robots into space.[93]

1990s

[edit]In 1994 one of the most successful robot-assisted surgery appliances was cleared by the FDA. The Cyberknife had been invented by John R. Adler and the first system was installed at Stanford University in 1991. This radiosurgery system integrated image-guided surgery with robotic positioning. The Cyberknife is now deployed to treat patients with brain or spine tumors. An x-ray camera tracks displacement and compensates for motion caused by breathing.[94]

The biomimetic robot RoboTuna was built by doctoral student David Barrett at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1996 to study how fish swim in water. RoboTuna is designed to swim and to resemble a bluefin tuna.[95]

Honda's P2 humanoid robot was first shown in 1996. Standing for "Prototype Model 2", P2 was an integral part of Honda's humanoid development project; over 6 feet (1.8 m) tall, P2 was smaller than its predecessors and appeared to be more human-like in its motions.[96]

Expected to operate for only seven days, the Sojourner rover finally shuts down after 83 days of operation in 1997. This small robot (only 23 lbs or 10.5 kg) performed semi-autonomous operations on the surface of Mars as part of the Mars Pathfinder mission; equipped with an obstacle avoidance program, Sojourner was capable of planning and navigating routes to study the surface of the planet. Sojourner's ability to navigate with little data about its environment and nearby surroundings allowed it to react to unplanned events and objects.[97]

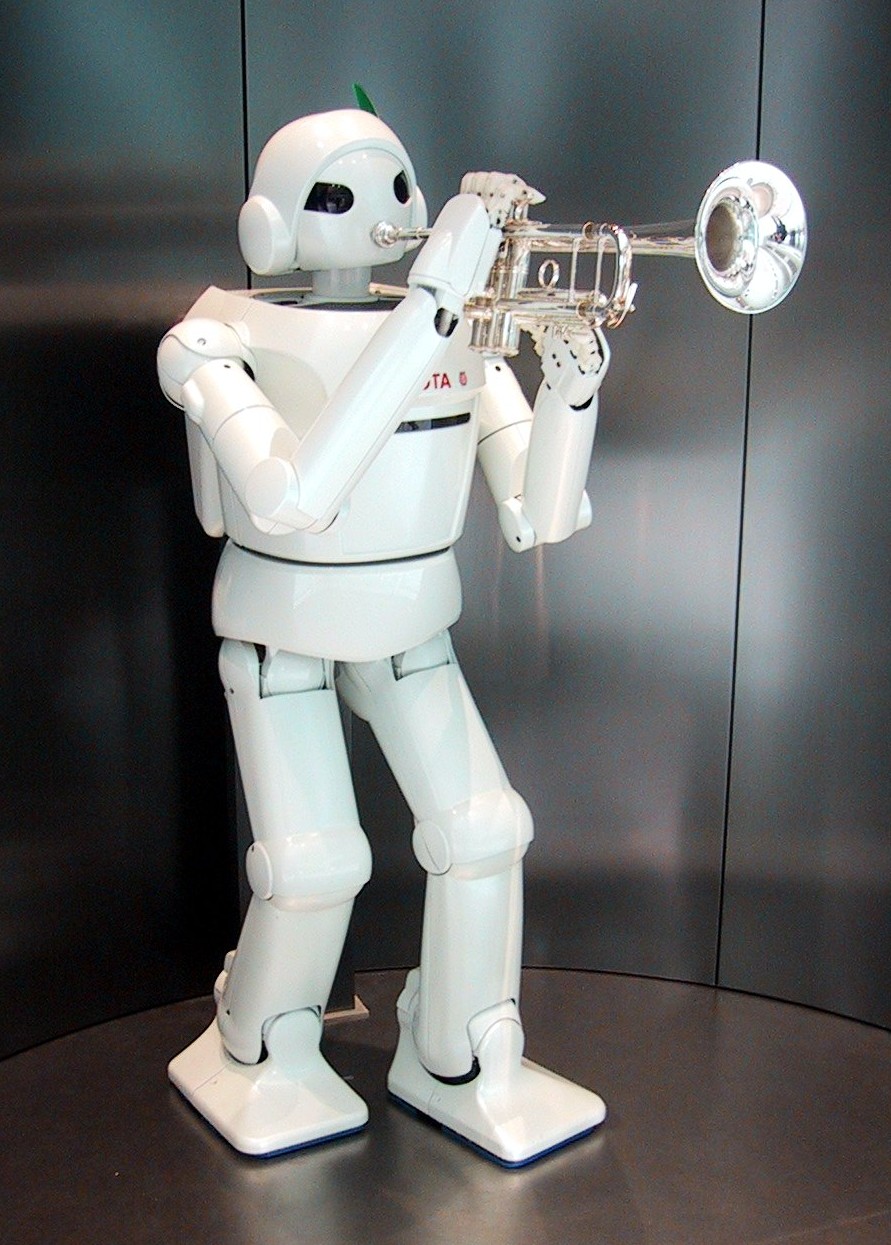

The P3 humanoid robot was revealed by Honda in 1998 as a part of the company's continuing humanoid project.[98] In 1999, Sony introduced the AIBO, a robotic dog capable of interacting with humans; the first models released in Japan sold out in 20 minutes.[99] Honda revealed the most advanced result of their humanoid project in 2000, named ASIMO. ASIMO can run, walk, communicate with humans, recognise faces, environment, voices and posture, and interact with its environment.[100] Sony also revealed its Sony Dream Robots, small humanoid robots in development for entertainment.[101] In October 2000, the United Nations estimated that there were 742,500 industrial robots in the world, with more than half of them being used in Japan.[31]

2000s

[edit]

In April 2001, the Canadarm2 was launched into orbit and attached to the International Space Station. The Canadarm2 is a larger, more capable version of the arm used by the Space Shuttle, and is hailed as "smarter".[102] Also in April, the Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Global Hawk made the first autonomous non-stop flight over the Pacific Ocean from Edwards Air Force Base in California to RAAF Base Edinburgh in Southern Australia. The flight was made in 22 hours.[103]

The popular Roomba, a robotic vacuum cleaner, was first released in 2002 by the company iRobot.[104]

In 2002, in her book Designing Sociable Robots, Cynthia Breazeal was one of the first to explore the idea of robots imitating humans, and published research on how, in the future, teaching humanoid robots to perform new tasks might be as simple as just showing them.[105] Throughout the early 2000s Breazeal was experimenting with expressive social exchange between humans and humanoid robots. Whilst completing her PhD at MIT, she worked on humanoid robots Kismet, Leonard, Aida, Autom and Huggable.[106] Doing this, Breazeal found that the issue was that robots too often only interacted with objects and not people and suggested that robots can be used to better relationships between humans.

In 2005, Cornell University revealed a robotic system of block-modules capable of attaching and detaching, described as the first robot capable of self-replication, because it was capable of assembling copies of itself if it was placed near more of the blocks which composed it.[107] Launched in 2003, on 3 and 24 January, the Mars rovers Spirit and Opportunity landed on the surface of Mars. Both robots drove many times the distance originally expected, and Opportunity was still operating as late as mid-2018, before communications were lost due to a major dust storm.[108]

Self-driving cars had made their appearance by around 2005, but there was room for improvement. None of the 15 devices competing in the DARPA Grand Challenge (2004) successfully completed the course; in fact no robot successfully navigated more than 5% of the 150-mile (240 km) off-road course, leaving the $1 million prize unclaimed.[109] In 2005, Honda revealed a new version of its ASIMO robot, updated with new behaviors and capabilities.[110] In 2006, Cornell University revealed its "Starfish" robot, a four-legged robot capable of self modeling[clarification needed] and learning to walk after having been damaged.[111] In 2007, TOMY launched the entertainment robot, i-sobot, a humanoid bipedal robot that can walk like a human and performs kicks and punches and also some entertaining tricks and special actions under "Special Action Mode".

2010s

[edit]The 2010s were defined by large-scale improvements in the availability, power and versatility of commonly available robotic components, as well as the mass proliferation of robots into everyday life, which caused both optimistic speculation and new societal concerns.

Development of humanoid robots continued to advance; Robonaut 2 was launched to the International Space Station aboard Space Shuttle Discovery on the STS-133 mission in 2011 as the first humanoid robot in space. While its initial purpose was to teach engineers how dextrous robots behave in space, the hope is that through upgrades and advancements, it could one day venture outside the station to help spacewalkers make repairs or additions to the station or perform scientific work.[112] By the end of the decade, humanoid and animal-like robots were capable of clearing difficult obstacle courses, maintaining balance, and even performing gymnastic feats.[113] However, the vast majority of robotic developments in the 2010s instead saw smaller, more specialized non-humanoid robots become cheaper, more capable, and more ubiquitous.

Moore's Law and the increasing integration of digital electronic components into lightweight and powerful systems on a chip allowed for the heavy computation necessary for the operation of a robotic system to be performed by smaller and smaller devices. Many of these advances in chip and sensor technology were driven by the growth and spread of smartphones, which demanded these new components to meet the increasing demands of everyday use.

The cost and weight reductions of these components have resulted in a proliferation of new kinds of special-purpose robots. Quadcopters, a novelty at the beginning of the decade, became a ubiquitous platform for robotic systems, featuring autonomous navigation and stabilization and carrying increasingly powerful sensors, including stabilized high definition cameras, radar, and surveying equipment. By the end of the decade, the cost of a robotic quadcopter with 4K cameras and autonomous navigation had dropped to within range of hobbyist budgets,[114] and companies like Amazon were exploring the use of quadcopters to autonomously deliver freight, though deployment of this systems did not happen on a large scale in the decade.[115]

The decade also saw a boom in the capabilities of artificial intelligence. Over the course of the 2010s, the capacity of onboard computers used within robots increased to the point that robots could perform increasingly complex actions without human guidance, as well as independently process data in more complex ways. The growth of mobile data networks and increasing power of graphics cards for artificial intelligence applications also allowed robots to communicate with distant clusters in real time, effectively boosting the capability of even very simple robots to include cutting-edge artificial intelligence techniques.

The 2010s also saw the growth of new software paradigms, which allowed robots and their AI systems to take advantage of this increased computing power. Neural networks became increasingly well developed in the 2010s, with companies like Google offering free and open access to products like TensorFlow, which allowed robot manufacturers to quickly integrate neural nets that allowed for abilities like facial recognition and object identification in even the smallest, cheapest robots.[116]

The growth of robots in the 2010s also coincided with the increasing power of the open source software movement, with many companies offering free access to their artificial intelligence software. Open source hardware, such as the Raspberry Pi line of compact single board computers and the Arduino line of microcontrollers, as well as a growing array of electronic components like sensors and motors dramatically increased in power and decreased in price over the 2010s. Combined with the drop in cost of manufacturing techniques like 3D printing, these components allowed hobbyists, researchers and manufacturers alike to quickly and cheaply build special-purpose robots that exhibited high degrees of artificial intelligence, as well as to share their designs with others around the world.

Self-driving cars transitioned from speculative to emergent during the decade. By the end of the decade, most new cars were manufactured with robotic subsystems capable of warning the car's human driver about dangers such as nearby vehicles or potential lane departures.[117] In 2014, new Tesla vehicles were fitted with the computer hardware necessary to eventually support a full autopilot software system, with increasingly autonomous software systems arriving as updates over later years.[118] By the end of the decade, autonomous driving was possible on large highways, but still required human supervision.[119]

The growth of robotic capabilities during the decade happened in tandem with the centralization of economic power into the hands of large multinational tech companies, which has prompted concerns that the capabilities of these robots could be abused by the companies that make them available to consumers. The acquisition of Roomba by Amazon led to concerns from data privacy advocates that data about the interiors of users' homes collected by the robots' sensors and cameras could be stored, shared and analyzed without those users' informed consent.[120] Likewise, the ubiquity of small flying quadcopters, home automation, and facial recognition capabilities by robots has caused serious concerns regarding human rights abuses, including allegations of repression of ethnic minorities in China[121] and concerns about violations of privacy rights by law enforcement in the United States.[122] As robotic systems showed the ability to perform more and more tasks once limited to human operators, many ethicists raised concerns that robots operating complex systems may not have the moral or ethical safeguards necessary to ensure public safety.[123]

Throughout the 2010s, humans continued to examine the nature of their relationships with robots, with trends indicating a general belief that robots were or would become conscious beings deserving of rights, and potential allies or rivals to humans. On 25 October 2017 at the Future Investment Summit in Riyadh, a robot called Sophia and referred to with female pronouns was granted Saudi Arabian citizenship, becoming the first robot ever to have a nationality.[124][125] This has attracted controversy, as it is not obvious whether this implies that Sophia can vote or marry, or whether a deliberate system shutdown can be considered murder; as well, it is controversial considering how few rights are given to Saudi human women.[126][127] Popular works of art in the 2010s, such as HBO's revival of Westworld, encouraged empathy for robots, and explored questions of humanity and consciousness.[128]

By the end of the decade, commercial and industrial robots were in widespread use, performing jobs more cheaply or with greater accuracy and reliability than humans, and were widely used in manufacturing, assembly and packing, transport, Earth and space exploration, surgery, weaponry, laboratory research, and mass production of consumer and industrial goods.[129] The growth of the use robots across industry, as well as in the service sector and in creative or highly skilled jobs formerly limited to humans, led to fears in the latter part of the decade of mass technological unemployment.[130]

By the very end of the decade, robotics had started to make advancements on the nanotechnology scale. In 2019, engineers at the University of Pennsylvania created millions of nanobots in just a few weeks using technology borrowed from the mature semiconductor industry. These microscopic robots, small enough to be injected into the human body and controlled wirelessly, could one day deliver medications and perform surgeries, revolutionizing medicine and health.[131]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Kourai Khryseai". Theoi Project. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ Deborah Levine Gera (2003). Ancient Greek Ideas on Speech, Language, and Civilization. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925616-7. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

- ^ Ronnie Littlejohn; Jeffrey Dippmann (2011). Riding the Wind with Liezi: New Perspectives on the Daoist Classic. SUNY Press. pp. 195–196. ISBN 978-1-4384-3455-1.

- ^ a b Ronnie Littlejohn; Jeffrey Dippmann (2011). Riding the Wind with Liezi: New Perspectives on the Daoist Classic. SUNY Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-1-4384-3455-1.

- ^ Ronnie Littlejohn; Jeffrey Dippmann (2011). Riding the Wind with Liezi: New Perspectives on the Daoist Classic. SUNY Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-1-4384-3455-1.

- ^ Ronnie Littlejohn; Jeffrey Dippmann (2011). Riding the Wind with Liezi: New Perspectives on the Daoist Classic. SUNY Press. pp. 194–195. ISBN 978-1-4384-3455-1.

- ^ Ronnie Littlejohn; Jeffrey Dippmann (2011). Riding the Wind with Liezi: New Perspectives on the Daoist Classic. SUNY Press. p. 197. ISBN 978-1-4384-3455-1.

- ^ Strong, J.S. (2007). Relics of the Buddha. Princeton University Press. pp. 133–134. ISBN 978-0-691-11764-5.

- ^ Adrienne Mayor (2018). Gods and Robots: Myths, Machines, and Ancient Dreams of Technology. Princeton University Press. pp. 205–206. ISBN 978-0-691-18544-6.

- ^ a b William Godwin (1876). "Lives of the Necromancers".

- ^ Haug, "Walewein as a postclassical literary experiment", pp. 23–4; Roman van Walewein, ed. G.A. van Es, De Jeeste van Walewein en het Schaakbord van Penninc en Pieter Vostaert (Zwolle, 1957): 877 ff and 3526 ff.

- ^ See also P. Sullivan, "Medieval Automata: The 'Chambre de beautés' in Benoît's Roman de Troie." Romance Studies 6 (1985): 1–20.

- ^ Currie, Adam (1999). "The History of Robotics". Archived from the original on 18 July 2006. Retrieved 10 September 2007.

- ^ Kevin LaGrandeur (2013). Androids and Intelligent Networks in Early Modern Literature and Culture: Artificial Slaves. Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-415-63121-1.

- ^ Kevin LaGrandeur (2013). Androids and Intelligent Networks in Early Modern Literature and Culture: Artificial Slaves. Routledge. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-415-63121-1.

- ^ Safran, Linda (1998). Heaven on Earth: Art and the Church in Byzantium. Pittsburgh: Penn State Press. p. 30. ISBN 0-271-01670-1. Records Liutprand's description.

- ^ "Su Song's Clock: 1088". Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- ^ a b c Hemal, Ashok K.; Menon, Mani (2018). Robotics in Genitourinary Surgery. Springer. p. 7. ISBN 978-3-319-20645-5.

- ^ a b Hemal, Ashok K.; Menon, Mani (2018). Robotics in Genitourinary Surgery. Springer. p. 8. ISBN 978-3-319-20645-5.

- ^ Kevin LaGrandeur (2013). Androids and Intelligent Networks in Early Modern Literature and Culture: Artificial Slaves. Routledge. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-415-63121-1.

- ^ al-Jazari (Islamic artist), Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Donald Hill (1996), A History of Engineering in Classical and Medieval Times, Routledge, p. 224

- ^ Ancient Discoveries, Episode 12: Machines of the East, History, 24 July 2008, archived from the original on 12 December 2021, retrieved 6 September 2008

- ^ Rosheim, Mark E. (1994), Robot Evolution: The Development of Anthrobotics, John Wiley & Sons, p. 9, ISBN 978-0-471-02622-8

- ^ "articles58". 29 June 2007. Archived from the original on 29 June 2007. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Rosheim, Mark E. (1994), Robot Evolution: The Development of Anthrobotics, John Wiley & Sons, p. 9, ISBN 978-0-471-02622-8

- ^ Kevin LaGrandeur (2013). Androids and Intelligent Networks in Early Modern Literature and Culture: Artificial Slaves. Routledge. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-415-63121-1.

- ^ a b Kevin LaGrandeur (2013). Androids and Intelligent Networks in Early Modern Literature and Culture: Artificial Slaves. Routledge. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-415-63121-1.

- ^ Truitt, Elly R. "The Garden of Earthly Delights: Mahaut of Artois and the Automata at Hesdin". Iowa Research Online, University of Iowa. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ a b Moran, Michael E. (December 2006). "The da Vinci robot". Journal of Endourology. 20 (12): 986–90. doi:10.1089/end.2006.20.986. PMID 17206888.

- ^ a b "Sir Richard Arkwright (1732–1792)". BBC. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- ^ a b c Ashok K. Hemal; Mani Menon (2018). Robotics in Genitourinary Surgery. Springer. p. 6. ISBN 978-3-319-20645-5.

- ^ Ashok K. Hemal; Mani Menon (2018). Robotics in Genitourinary Surgery. Springer. p. 5. ISBN 978-3-319-20645-5.

- ^ Armand Mattelart (1996). The Invention of Communication. University of Minnesota Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8166-2697-7.

- ^ T. N. Hornyak (2006). Loving the Machine: The Art and Science of Japanese Robots. Kodansha International.

- ^ Lisa Nocks (2006). The Robot: The Life Story of a Technology. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-313-33168-8.

- ^ Gizycki, Jerzy. A History of Chess. London: Abbey Library, 1972. Print.

- ^ Alex Goody (2011). Technology, Literature and Culture: Themes in twentieth and twenty-first-century literature and culture. Polity. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-7456-3954-3.

- ^ Sarkar 2006, page 97

- ^ A. P. Yuste. Electrical Engineering Hall of Fame. Early Developments of Wireless Remote Control: The Telekino of Torres-Quevedo,(pdf) vol. 96, No. 1, January 2008, Proceedings of the IEEE.

- ^ H. R. Everett, Unmanned Systems of World Wars I and II, MIT Press - 2015, pages 91-95

- ^ "1902 – Telekine (Telekino) – Leonardo Torres Quevedo (Spanish)". 17 December 2010.

- ^ Williams, Andrew (16 March 2017). History of Digital Games: Developments in Art, Design and Interaction. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-317-50381-1.

- ^ Brian Randell, From Analytical Engine to Electronic Digital Computer: The Contributions of Ludgate, Torres and Bush. Annals of the History of Computing, Vol. 4, No. 4, Oct. 1982

- ^ Hooper & Whyld 1992 page 22. The Oxford Companion to Chess (2nd ed.). England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866164-9.

- ^ L. Torres Quevedo. Ensayos sobre Automática - Su definicion. Extension teórica de sus aplicaciones, Revista de la Academia de Ciencias Exacta, Revista 12, pp.391-418, 1914.

- ^ Torres Quevedo. L. (1915). "Essais sur l'Automatique - Sa définition. Etendue théorique de ses applications", Revue Génerale des Sciences Pures et Appliquées, vol. 2, pp. 601–611.

- ^ B. Randell. Essays on Automatics, The Origins of Digital Computers, pp.89-107, 1982.

- ^ McCorduck, Pamela (2004), Machines Who Think (2nd ed.), Natick, MA: A. K. Peters, Ltd., pp. 59–60, ISBN 978-1-56881-205-2, OCLC 52197627.

- ^ Ashok K. Hemal; Mani Menon (2018). Robotics in Genitourinary Surgery. Springer. p. 4. ISBN 978-3-319-20645-5.

- ^ "R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots)". Archived from the original on 26 August 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac; Frenkel, Karen (1985). Robots: Machines in Man's Image. New York: Harmony Books. p. 13.

- ^ "The checkered history of automation". newatlas.com. 10 November 2008. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ^ "MegaGiantRobotics". Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- ^ "AH Reffell & Eric Robot (1928)". Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ Lisa Nocks (2006). The Robot: The Life Story of a Technology. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-0-313-33168-8.

- ^ "Robot Dreams : The Strange Tale of a Man's Quest To Rebuild His Mechanical Childhood Friend". The Cleveland Free Times. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- ^ Scott Schaut (2006). Robots of Westinghouse: 1924-Today. Mansfield Memorial Museum. ISBN 0-9785844-1-4.

- ^ "Japan's first-ever robot". Yomiuri.co.jp. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ Armin Krishnan (2016). Killer Robots: Legality and Ethicality of Autonomous Weapons. Routledge. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-317-10912-9.

- ^ Lisa Nocks (2006). The Robot: The Life Story of a Technology. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-313-33168-8.

- ^ Lisa Nocks (2006). The Robot: The Life Story of a Technology. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-313-33168-8.

- ^ Lisa Nocks (2006). The Robot: The Life Story of a Technology. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-313-33168-8.

- ^ Owen Holland. "The Grey Walter Online Archive". Archived from the original on 9 October 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- ^ "George Devol Listing at National Inventor's Hall of Fame".

- ^ Waurzyniak, Patrick (July 2006). "Masters of Manufacturing: Joseph F. Engelberger". Society of Manufacturing Engineers. 137 (1). Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- ^ Ashok K. Hemal; Mani Menon (2018). Robotics in Genitourinary Surgery. Springer. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-3-319-20645-5.

- ^ Lisa Nocks (2006). The Robot: The Life Story of a Technology. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-313-33168-8.

- ^ Lisa Nocks (2006). The Robot: The Life Story of a Technology. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-313-33168-8.

- ^ "Robot Hall of Fame – Unimate". Carnegie Mellon University. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- ^ Mickle, Paul. "1961: A peep into the automated future", The Trentonian. Accessed 11 August 2011.

- ^ "National Inventor's Hall of Fame 2011 Inductee". Invent Now. Archived from the original on 4 November 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f "Computer History Museum – Timeline of Computer History". Retrieved 30 August 2007.

- ^ Ashok K. Hemal; Mani Menon (2018). Robotics in Genitourinary Surgery. Springer. p. 9. ISBN 978-3-319-20645-5.

- ^ Armin Krishnan (2016). Killer Robots: Legality and Ethicality of Autonomous Weapons. Routledge. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-317-10912-9.

- ^ a b Armin Krishnan (2016). Killer Robots: Legality and Ethicality of Autonomous Weapons. Routledge. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-317-10912-9.

- ^ Robotics and Mechatronics: Proceedings of the 4th IFToMM International Symposium on Robotics and Mechatronics, page 66

- ^ "Humanoid History -WABOT-".

- ^ Robots: From Science Fiction to Technological Revolution, page 130

- ^ Handbook of Digital Human Modeling: Research for Applied Ergonomics and Human Factors Engineering, Chapter 3, pages 1-2

- ^ "Edinburgh Freddy Robot". Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- ^ "first industrial robot with six electromechanically driven axes KUKA's FAMULUS". Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- ^ "1960 - Rudy the Robot - Michael Freeman (American)". cyberneticzoo.com. 13 September 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ The Futurist. World Future Society. 1978. pp. 152, 357, 359.

- ^ Colligan, Douglas (30 July 1979). The Robots Are Comming. New York Magazine.

- ^ "The Robot Hall of Fame : AIBO". Archived from the original on 6 September 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- ^ "Robotics Institute: About the Robotics Institute". Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- ^ "Cobot - collaborative robot". peshkin.mech.northwestern.edu.

- ^ "Takeo Kanade Collection: Envisioning Robotics: Direct Drive Robotic Arms". Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- ^ "2history". Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- ^ "P3". Honda Worldwide. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- ^ Angle, Colin (1989). Genghis, a six-legged autonomous walking robot (Thesis). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. hdl:1721.1/14531.

- ^ "Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control: A Robot Invasion of The Solar System" (PDF). Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- ^ Habib, Maki K. (2014). Handbook of Research on Advancements in Robotics and Mechatronics. IGI Global. p. 253. ISBN 978-1-4666-7388-5.

- ^ "Something's Fishy about this Robot". Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- ^ "ASIMO". Honda Worldwide. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- ^ "The Robot Hall of Fame : Mars Pathfinder Sojourner Rover". Archived from the original on 7 October 2007. Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- ^ "The Honda Humanoid Robots". Archived from the original on 11 September 2007. Retrieved 10 September 2007.

- ^ "AIBOaddict! About". Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 10 September 2007.

- ^ "ASIMO". Honda Worldwide – Technology. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 10 September 2007.

- ^ Williams, Martyn (21 November 2000). "Technology – Sony unveils prototype humanoid robot – November 22, 2000". CNN. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ^ "NASA – Canadarm2 and the Mobile Servicing System". Archived from the original on 23 March 2009. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ^ "Global Hawk Flies Unmanned Across Pacific". Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ^ "Maid to Order". Time. 14 September 2002. Archived from the original on 13 August 2007. Retrieved 15 September 2007.

- ^ Breazeal, Cynthia. "Robots that Imitate Humans". MIT Media Lab. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ Breazeal, Cynthia; Brooks, Rodney (28 April 2005), Fellous, Jean-Marc; Arbib, Michael A. (eds.), "Robot Emotion", Who Needs Emotions?, Oxford University Press, pp. 271–310, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195166194.003.0010, ISBN 978-0-19-516619-4, retrieved 8 October 2024

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ "Self-replicating blocks from Cornell University". YouTube. 2 February 2009. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ "Mars Opportunity Rover Mission: Status Reports". Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ "Robots fail to complete Grand Challenge – Mar 14, 2004". CNN. 6 May 2004. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ^ "Honda Debuts New ASIMO". Honda Worldwide. 13 December 2005. Archived from the original on 20 July 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2007.

- ^ "Cornell CCSL: Robotics Self Modeling". Retrieved 15 September 2007.

- ^ "Robonaut | NASA". Nasa.gov. 9 December 2013. Archived from the original on 6 November 2010. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ Snider, Mike. "Boston Dynamics' latest robot video shows its 5-foot humanoid robot has moves like Simone Biles". USA TODAY. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "Months after launch, the DJI Mavic 3 is a much better drone". Engadget. 30 June 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "Amazon Prime Air prepares for drone deliveries". US About Amazon. 13 June 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "TensorFlow". TensorFlow. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "Lane Departure Warning & Lane Keeping Assist". Consumer Reports. 9 May 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "Tesla Autopilot Archives". Electrek. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "Tesla cars on autopilot have stopped on highways without cause, owners report". the Guardian. Associated Press. 3 June 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ Johnson, Khari. "The iRobot Deal Would Give Amazon Maps Inside Millions of Homes". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "AI emotion-detection software tested on Uyghurs". BBC News. 25 May 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ Guariglia, Jason Kelley and Matthew (15 July 2022). "Ring Reveals They Give Videos to Police Without User Consent or a Warrant". Electronic Frontier Foundation. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ Maxmen, Amy (24 October 2018). "Self-driving car dilemmas reveal that moral choices are not universal". Nature. 562 (7728): 469–470. Bibcode:2018Natur.562..469M. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-07135-0. PMID 30356197. S2CID 53023323.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia gives citizenship to a non-Muslim, English-Speaking robot". Newsweek. 26 October 2017.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia bestows citizenship on a robot named Sophia". TechCrunch. 26 October 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia takes terrifying step to the future by granting a robot citizenship". AV Club. 26 October 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia criticized for giving female robot citizenship, while it restricts women's rights". ABC News. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ^ "Westworld review – HBO's seamless marriage of robot cowboys and corporate dystopia". the Guardian. 5 October 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "About us". Archived from the original on 9 January 2014.

- ^ Douglas, Jacob (7 November 2019). "These American workers are the most afraid of A.I. taking their jobs". CNBC. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ Carne, Nick (8 March 2019). "Researchers make a million tiny robots". Cosmos Magazine. Archived from the original on 8 March 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

References

[edit]- Haug, Walter. "The Roman van Walewein as a postclassical literary experiment." In Originality and Tradition in the Middle Dutch Roman van Walewein, ed. B. Besamusca and E. Kooper. Cambridge, 1999. 17–28.

Further reading

[edit]- Balafrej, Lamia (2022). "Automated Slaves, Ambivalent Images, and Noneffective Machines in al-Jazari's Compendium of the Mechanical Arts, 1206". 21: Inquiries into Art, History, and the Visual. 3 (4): 737–774. doi:10.11588/xxi.2022.4.91685. ISSN 2701-1569.

- Baumgartner, Emmanuèlle. "Le temps des automates." In Le Nombre du temps, en hommage à Paul Zumthor. Paris: Champion, 1988. pp. 15–21.

- Brett, G. "The Automata in the Byzantine 'Throne of Solomon'." Speculum 29 (1954): 477–87.

- Glaser, Horst Albert and Rossbach, Sabine: The Artificial Human, Frankfurt/M., Bern, New York 2011 "The Artificial Human. A Tragical History", ebook "The Artificial Humans. A Real History of Robots, Androids, Replicants, Cyborgs, Clones and all the rest"

- Sullivan, P. "Medieval Automata: The 'Chambre de beautés' in Benoît's Roman de Troie." Romance Studies 6 (1985). pp. 1–20.

- History of Robots in 10 Minutes. Archived 20 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine

History of robots

View on GrokipediaMythological and Ancient Precursors

Legends and Myths

In Greek mythology, the smith-god Hephaestus forged automatons including self-moving golden tripods that could enter and exit his workshop autonomously and twenty tripods equipped with wheels for mobility.[9] These devices, described in Homer's Iliad (circa 8th century BCE), assisted in divine labors, embodying early imaginative concepts of mechanical agency without explicit human operation.[10] Hephaestus also created golden handmaidens—android-like figures with lifelike appearance, speech, and perception—programmed to accompany and aid him, highlighting mythical precedents for artificial intelligence integrated into humanoid forms.[9] Talos, a colossal bronze automaton forged by Hephaestus or commissioned by Zeus, served as guardian of Crete, patrolling its perimeter three times daily while hurling boulders at approaching ships to repel invaders.[11] Powered by a single vein of ichor connected to a protective nail at its ankle, Talos represented a sentinel mechanism vulnerable to precise disruption, as depicted in accounts from Apollonius Rhodius' Argonautica (3rd century BCE) where the Argonauts exploited this weakness.[12] This legend, rooted in Minoan-era folklore adapted into Hellenic narratives, illustrates rudimentary ideas of programmed patrol and defensive autonomy. The legendary artisan Daedalus, credited with inventing labyrinthine architecture, also crafted statues so animated and deceptive in their lifelikeness that they required binding with chains to prevent escape, as referenced in Plato's Meno (circa 380 BCE).[13] These "living" effigies, attributed to Daedalus' unparalleled mimetic skill, blurred boundaries between sculpture and sentience in myth, influencing philosophical discussions on the instability of artificial forms, as Aristotle echoed in Politics (circa 350 BCE).[14] In Jewish folklore, the golem—an anthropomorphic entity formed from clay and animated via rabbinic rituals invoking divine names—emerged as a protector against persecution, with the most enduring tale involving 16th-century Rabbi Judah Loew of Prague creating one to defend the ghetto.[15] Lacking true speech or independent will, the golem obeyed commands but grew uncontrollable, necessitating deactivation by erasing the animating word emeth (truth) from its forehead to revert it to meth (death).[15] This motif, drawn from Talmudic references to Adam as a proto-golem (Sanhedrin 65b, circa 500 CE), underscores causal limits of artificial creation, where obedience derives from imposed linguistics rather than innate cognition.Early Mechanical Automata

The earliest known mechanical automaton was constructed by the Greek philosopher and mathematician Archytas of Tarentum around 400–350 BCE, consisting of a steam-powered wooden pigeon that achieved sustained flight for approximately 200 meters along a guide wire before landing and perching.[16] This device utilized a boiler to generate steam jet propulsion, marking the first documented self-propelled flying mechanism, though its description survives only in later accounts by Aulus Gellius from the 2nd century CE.[17] During the Hellenistic era, pneumatic and hydraulic technologies enabled more intricate automata, as evidenced by the works of engineers in Alexandria. Ctesibius (c. 285–222 BCE), founder of the Alexandrian school of mechanics, developed water clocks (clepsydrae) incorporating moving figures driven by falling water weights, which animated indicators and chimes to mark time intervals.[18] His innovations in compressed air and siphons laid groundwork for subsequent devices, though surviving evidence relies on fragments preserved in later texts by Vitruvius and Hero.[18] Hero of Alexandria (c. 10–70 CE) advanced these principles in treatises such as Pneumatica and Automata, describing over 100 mechanisms powered by air pressure, steam, and counterweights. Notable examples include automated temple doors that opened via thermal expansion of air heated by an altar fire, triggering a hydraulic system to lift barriers; a coin-operated vending machine dispensing fixed measures of holy water upon detecting a drachma's weight and size through a slot and lever; and miniature programmable theaters up to 6 feet tall, where falling weights rotated axles connected to cords, pulleys, and cams to orchestrate scenes with moving figures, scenery changes, and sound effects lasting up to 10 minutes.[19] These constructs, often employing binary-like rope knots for sequencing, demonstrated rudimentary automation for entertainment and ritual but remained constrained by material limitations like unreliable seals and short operational durations, with no evidence of replication at scale.[19] Hero's aeolipile, a spinning steam turbine, further illustrated reactive motion principles, though it served demonstrative rather than propulsive purposes.[20]Medieval to Enlightenment Developments

Islamic and Byzantine Innovations

In the 9th century, the Byzantine Empire developed sophisticated mechanical automata primarily for imperial display and diplomatic intimidation. Leo the Mathematician constructed devices for Emperor Theophilos (r. 829–842), including a golden tree in the Magnaura Palace adorned with mechanical birds that sang and flapped wings, and roaring lions positioned at the throne's base.[21] These automata, powered by hidden mechanisms such as weights and pulleys, activated during audiences to awe foreign envoys, with the throne itself rising via mechanical lifts to enhance the emperor's divine aura.[22] Later, Emperor Constantine VII (r. 913–959) imported automata-makers from Baghdad to expand these displays, incorporating moving statues and self-operating devices that drew on Hellenistic precedents adapted for political theater.[23] During the Islamic Golden Age, engineers advanced automata toward more functional and programmable designs, building on earlier Hellenistic and Persian influences. Ismail al-Jazari (c. 1136–1206), a polymath serving the Artuqid dynasty in Mesopotamia, documented over 100 mechanical devices in his 1206 treatise The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices, including humanoid automata for practical tasks.[24] Notable examples encompass a hand-washing servant figure that dispensed soap and water via hidden floats and faucets, mimicking human service, and a programmable musical boat with four humanoid musicians—drummer, flautist, harpist, and cymbalist—that performed sequenced actions using pegged cylinders akin to early cam mechanisms.[25] Al-Jazari's elephant clock featured oscillating figures and a mechanical bird to mark hours, integrating hydraulics and gears for automated timekeeping with moving automata.[26] These innovations emphasized feedback control and sequential operations, precursors to cybernetic principles, though primarily for entertainment, hygiene, and irrigation rather than labor automation. Al-Jazari's detailed blueprints enabled replication and influenced subsequent engineering, with devices like the "castle clock" incorporating escapement mechanisms for precise timing and animated displays.[24] Byzantine and Islamic automata shared cross-cultural exchanges, as evidenced by Abbasid influences on Constantinopolitan designs, yet diverged in application: Byzantine focused on spectacle, Islamic on utility and ingenuity.[23]European Automata and Clockwork Devices

In medieval Europe, accounts of automata were largely legendary, such as the 13th-century tale attributed to Franciscan friar Roger Bacon, who supposedly constructed a brazen head capable of speech and prophecy after years of labor, though no archaeological or documentary evidence confirms its existence.[27] These stories reflected early aspirations for mechanical simulation of intelligence but lacked empirical realization. During the Renaissance, Leonardo da Vinci designed a humanoid automaton known as the mechanical knight around 1495, consisting of a German suit of armor housing an internal system of pulleys, cables, and clockwork gears that enabled it to sit, stand, and wave its arms in a programmed sequence.[28] While sketches survive in his notebooks, no contemporary records indicate da Vinci built the device, though modern reconstructions have demonstrated its feasibility using period materials and techniques.[29] The 16th century saw the production of actual clockwork figures by European goldsmiths, particularly in central regions like Augsburg, including a mechanical monk automaton dated to that era, constructed from iron and wood with integrated clock mechanisms to perform repetitive actions such as walking and praying.[30] These devices, often table ornaments or curiosities for nobility, advanced gear trains and escapements derived from horology, enabling sustained autonomous motion. In the 18th-century Enlightenment, French inventor Jacques de Vaucanson created the Digesting Duck in 1739, a life-sized automaton with over 400 moving parts per wing that flapped realistically, ingested grain, and simulated digestion by excreting processed matter via concealed mechanisms, though later analysis revealed the "digestion" as a sleight involving pre-ground paste.[31] Vaucanson's earlier flute-playing android from 1738 further showcased bellows and articulated fingers for musical performance, influencing studies in biomechanics. Swiss watchmakers Pierre Jaquet-Droz, his son Henri-Louis, and associate Jean-Frédéric Leschot produced three renowned humanoid automata between 1768 and 1774: The Draughtsman, which sketched four predefined images using a cam-driven system; The Writer, programmable to compose up to 40 customizable letters via interchangeable cams; and The Musician, a girl figure playing a full organ with moving lips and eyes.[32] Preserved today, these 18th-century marvels employed over 2,000 components each, exemplifying precision engineering that blurred lines between mechanism and mimicry of human dexterity.19th-Century Conceptual and Literary Foundations

Scientific and Fictional Origins

In the early 19th century, European literature introduced conceptual frameworks for artificial beings that mimicked human form and agency, laying fictional groundwork for later robotic ideas. E.T.A. Hoffmann's short story Der Sandmann (1816) featured Olympia, an automaton constructed by the inventor Coppelius and presented as a lifelike daughter, capable of singing and dancing in a manner that blurred distinctions between machine and human, evoking psychological disturbance in the protagonist Nathanael.[33] This depiction anticipated concerns over deceptive artificiality and the "uncanny" effect of machines simulating life, themes echoed in Freud's later analysis of the story as emblematic of automaton fascination.[34] Mary Shelley's Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818) further advanced these notions by portraying Victor Frankenstein's assembly of a sentient creature from biological parts through chemical and galvanic processes, raising questions of creator responsibility and the perils of unchecked scientific ambition in animating non-organic or reassembled matter.[35] The narrative's "Frankenstein complex"—a term later coined by Isaac Asimov to describe innate human dread of self-willed machines—highlighted causal risks of artificial entities rebelling against their makers, influencing subsequent science fiction on autonomous agents.[36] These works shifted from mere mechanical toys to ethical explorations of agency, autonomy, and the boundaries between organic and synthetic life, without relying on purely mechanical constructs but emphasizing scientific intervention. Scientifically, 19th-century innovations in computation and mechanics provided theoretical precursors to robotic control systems. Charles Babbage's Difference Engine (conceived 1822) and Analytical Engine (designed 1837) represented the first efforts at general-purpose programmable machines, using punched cards for instructions and capable of iterative calculations, which foreshadowed algorithmic control in automated devices.[37] Babbage's examination of the hoax automaton "The Turk"—a chess-playing fake exposed in the 1820s—spurred his interest in mechanical intelligence limits, prompting designs that integrated feedback mechanisms akin to later cybernetic principles.[37] Concurrently, advances in electromechanics, such as Michael Faraday's invention of the electric motor (1821), enabled precise motion control, while James Clerk Maxwell's mathematical analysis of governors (1868) formalized stability in self-regulating machines, essential for robotic autonomy.[1] These developments emphasized deterministic causation over mysticism, grounding future robotics in empirical engineering rather than anthropomorphic fantasy.Early Electromechanical Prototypes

In the late 19th century, the integration of electric motors, batteries, and nascent wireless technologies enabled the first rudimentary electromechanical devices with programmable or remote behaviors, transitioning from purely mechanical automata to systems incorporating electrical actuation and control. Practical electric motors, developed following Michael Faraday's 1821 experiments with electromagnetic rotation, became viable for small-scale applications by the 1870s through improvements in dynamos and accumulators, allowing inventors to power mechanical figures beyond steam or clockwork limitations. Nikola Tesla advanced this field significantly with his 1898 demonstration of a radio-controlled boat, recognized as an early electromechanical prototype for remote manipulation. On November 8, 1898, Tesla patented "Method of and Apparatus for Controlling Mechanism of Moving Vessels or Vehicles" (U.S. Patent No. 613,809), describing a system using radio-frequency signals to direct electric motors in a steel-hulled vessel approximately 1 meter long. At Madison Square Garden's electrical exhibition, the boat executed commands transmitted wirelessly—such as forward motion, turns, and stops—via tuned circuits, without visible wires or operators aboard, astonishing audiences and foreshadowing teleoperated robotics.[38] Tesla's design employed a receiver that converted radio impulses into motor activations, enabling selective response to specific frequencies, a principle foundational to later robotic control hierarchies.[39] He explicitly extended the concept to "automatons" in lectures, proposing machines that could execute pre-programmed sequences autonomously after initial wireless setup, though practical implementation awaited 20th-century electronics.[40] Contemporary literary concepts, while not physical prototypes, reflected and influenced electromechanical ideation amid these technical advances. Dime novels serialized by Luis Senarens (as "Noname") featured battery-powered androids like the "Electric Man" in 1885 stories involving fictional inventor Frank Reade Jr., depicting humanoid figures with electric locomotion for tasks such as exploration or labor, powered by emerging lead-acid batteries invented by Gaston Planté in 1859.[41] These narratives, drawing from real electric motor demonstrations at world's fairs (e.g., 1889 Paris Exposition), popularized the notion of electrically animated mechanical men, though no verified builds materialized until borderline-20th-century efforts like Louis Philip Perew's circa-1900 electric walking automaton, which used storage batteries to propel a figure pulling a sulky at speeds up to 3 mph.[42] Tesla's verifiable apparatus thus stands as the era's principal electromechanical milestone, bridging empirical electrical engineering with proto-robotic functionality, unencumbered by the hoaxes or illusions plaguing earlier mechanical entertainments.[43]Generations of Robots

Robots are commonly classified into five generations based on historical and technological evolution, though classifications vary slightly across sources. No universal technical specifications define entire generations, as they encompass broad categories with varying payloads, degrees of freedom, and actuators by model; however, key characteristics trace progression in autonomy, sensing, and intelligence.[44] The first generation (1950s–1960s/1970s) featured simple manipulator arms with fixed, pre-programmed sequences in open-loop control, lacking sensors or feedback. Hydraulic or electric actuators enabled precise, repetitive tasks like material handling. The Unimate hydraulic arm, weighing about 3,000 pounds, exemplifies this era's focus on industrial basics. Second-generation robots (1960s/1970s–1980s) added programmability, sensors, and closed-loop feedback for improved precision and adaptation to variables, advancing to assembly and inspection with basic environmental perception. Third-generation systems (1970s/1980s–1990s) integrated sensors for vision and touch, self-programming, adaptive control, and computer reprogrammability, allowing environmental interaction and operator collaboration alongside enhanced error handling. Fourth-generation robots (1990s–2010s/2020s) incorporated advanced computing, AI, learning, and logic for intelligence; collaborative cobots facilitated human interaction with sophisticated sensors and tools like the Robot Operating System (ROS). Examples include the Roomba autonomous vacuum and ABB's YuMi dual-arm cobot. The fifth generation (2020s–present) relies on deep learning, large language models, and AI-driven decision-making for full autonomy; modular and reconfigurable designs prioritize human-centric integration into dynamic environments with minimal intervention. Overall, generations progress from fixed programming and repetition in early industrial applications to adaptive, intelligent, and collaborative systems emphasizing versatility, safety, and non-manufacturing uses like consumer services.Birth of Programmable Industrial Robots

Patent and Invention Milestones