Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Type (biology)

View on Wikipedia

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally associated. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes the defining features of that particular taxon. In older usage (pre-1900 in botany), a type was a taxon rather than a specimen.[1]

A taxon is a scientifically named grouping of organisms with other like organisms, a set that includes some organisms and excludes others, based on a detailed published description (for example a species description) and on the provision of type material, which is usually available to scientists for examination in a major museum research collection, or similar institution.[1][2]

Type specimen

[edit]

According to a precise set of rules laid down in the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) and the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICN), the scientific name of every taxon is almost always based on one particular specimen, or in some cases specimens. Types are of great significance to biologists, especially to taxonomists. Types are usually physical specimens that are kept in a museum or herbarium research collection, but failing that, an image of an individual of that taxon has sometimes been designated as a type.[3] Describing species and appointing type specimens is part of scientific nomenclature and alpha taxonomy.

When identifying material, a scientist attempts to apply a taxon name to a specimen or group of specimens based on their understanding of the relevant taxa,[clarification needed][citation needed] based on (at least) having read the type description(s),[citation needed] preferably also based on an examination of all the type material of all of the relevant taxa. If there is more than one named type that all appear to be the same taxon, then the oldest name takes precedence and is considered to be the correct name of the material in hand. If on the other hand, the taxon appears never to have been named at all, then the scientist or another qualified expert picks a type specimen and publishes a new name and an official description.[citation needed]

Depending on the nomenclature code applied to the organism in question, a type can be a specimen, a culture, an illustration, or (under the bacteriological code) a description.[4][5][6]

For example, in the research collection of the Natural History Museum in London, there is a bird specimen numbered 1886.6.24.20. This is a specimen of a kind of bird commonly known as the spotted harrier, which currently bears the scientific name Circus assimilis. This particular specimen is the holotype for that species; the name Circus assimilis refers, by definition, to the species of that particular specimen. That species was named and described by Jardine and Selby in 1828, and the holotype was placed in the museum collection so that other scientists might refer to it as necessary.[citation needed]

At least for type specimens there is no requirement for a "typical" individual to be used. Genera and families, particularly those established by early taxonomists, tend to be named after species that are more "typical" for them, but here too this is not always the case and due to changes in systematics cannot be. Hence, the term name-bearing type or onomatophore is sometimes used, to denote the fact that biological types do not define "typical" individuals or taxa, but rather fix a scientific name to a specific operational taxonomic unit. Type specimens are theoretically even allowed to be aberrant or deformed individuals or color variations, though this is rarely chosen to be the case, as it makes it hard to determine to which population the individual belonged.[1][2][7]

The usage of the term type is somewhat complicated by slightly different uses in botany and zoology. In the PhyloCode, type-based definitions are replaced by phylogenetic definitions.[citation needed]

Older terminology

[edit]In some older taxonomic works the word "type" has sometimes been used differently. The meaning was similar in the first Laws of Botanical Nomenclature,[8][9] but has a meaning closer to the term taxon in some other works:[10]

Ce seul caractère permet de distinguer ce type de toutes les autres espèces de la section. ... Après avoir étudié ces diverses formes, j'en arrivai à les considérer comme appartenant à un seul et même type spécifique.

Translation: This single character permits [one to] distinguish this type from all other species of the section ... After studying the diverse forms, I came to consider them as belonging to the one and the same specific type.

In botany

[edit]In botanical nomenclature, a type (typus, nomenclatural type), "is that element to which the name of a taxon is permanently attached." (article 7.2)[11] In botany, a type is either a specimen or an illustration. A specimen is a real plant (or one or more parts of a plant or a lot of small plants), dead and kept safe, "curated", in a herbarium (or the equivalent for fungi). Examples of where an illustration may serve as a type include:

- A detailed drawing, painting, etc., depicting the plant, from the early days of plant taxonomy. A dried plant was difficult to transport and hard to keep safe for the future; many specimens from the early days of botany have since been lost or damaged. Highly skilled botanical artists were sometimes employed by a botanist to make faithful and detailed illustrations. Some such illustrations have become the best record and have been chosen to serve as the type of taxon.

- A detailed picture of something that can be seen only through a microscope. A tiny "plant" on a microscope slide makes for a poor type: the microscope slide may be lost or damaged, or it may be very difficult to find the "plant" in question among whatever else is on the microscope slide. An illustration makes for a much more reliable type (Art 37.5 of the Vienna Code, 2006).

A type does not determine the circumscription of the taxon. For example, the common dandelion is a controversial taxon: some botanists consider it to consist of over a hundred species, and others regard it as a single species. The type of the name Taraxacum officinale is the same whether the circumscription of the species includes all those small species (Taraxacum officinale is a "big" species) or whether the circumscription is limited to only one small species among the other hundred (Taraxacum officinale is a "small" species). The name Taraxacum officinale is the same and the type of the name is the same, but the extent to which the name actually applies varies greatly. Setting the circumscription of a taxon is done by a taxonomist in a publication.

Miscellaneous notes:

- Only a species or an infraspecific taxon can have a type of its own. For most new taxa (published on or after 1 January 2007, article 37) at these ranks, a type should not be an illustration.

- A genus has the same type as that of one of its species (article 10).

- A family has the same type as that of one of its genera (article 10).

The ICN provides a listing of the various kinds of types (article 9 and the Glossary),[11] the most important of which is the holotype. These are

- holotype – the single specimen or illustration that the author(s) clearly indicated to be the nomenclatural type of a name

- lectotype – a specimen or illustration designated from the original material as the nomenclatural type when there was no holotype specified or the holotype has been lost or destroyed

- isotype – a duplicate of the holotype

- syntype – any specimen (or illustration) cited in the original description when there is no holotype, or any one of two or more specimens simultaneously designated as types

- paratype – any specimen (or illustration) cited in the original description that is not the holotype nor an isotype, nor one of the syntypes

- neotype – a specimen or illustration selected to serve as nomenclatural type if no material from the original description is available

- epitype – a specimen or illustration selected to serve as an interpretative type, usually when another kind of type does not show the critical features needed for identification

The word "type" appears in botanical literature as a part of some older terms that have no status under the ICN: for example a clonotype.

In zoology

[edit]

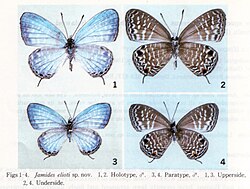

1) dorsal and 2) ventral aspect of holotype,

3) dorsal and 4) ventral aspect of paratype

In zoological nomenclature, the type of a species or subspecies is a specimen or series of specimens. The type of a genus or subgenus is a species. The type of a suprageneric taxon (e.g., family, etc.) is a genus. Names higher than superfamily rank do not have types. A "name-bearing type" is a specimen or image that "provides the objective standard of reference whereby the application of the name of a nominal taxon can be determined."[citation needed]

Definitions

[edit]- A type specimen is a vernacular term (not a formally defined term) typically used for an individual or fossil that is any of the various name-bearing types for a species. For example, the type specimen for the species Homo neanderthalensis was the specimen "Neanderthal-1" discovered by Johann Karl Fuhlrott in 1856 at Feldhofer in the Neander Valley in Germany, consisting of a skullcap, thigh bones, part of a pelvis, some ribs, and some arm and shoulder bones. There may be more than one type specimen, but there is (at least in modern times) only one holotype.

- A type species is the nominal species that is the name-bearing type of a nominal genus or subgenus.

- A type genus is the nominal genus that is the name-bearing type of a nominal family-group taxon.

- The type series are all those specimens included by the author in a taxon's formal description, unless the author explicitly or implicitly excludes them as part of the series.

Use of type specimens

[edit]

Although in reality biologists may examine many specimens (when available) of a new taxon before writing an official published species description, nonetheless, under the formal rules for naming species (the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature), a single type must be designated, as part of the published description.[citation needed]

A type description must include a diagnosis (typically, a discussion of similarities to and differences from closely related species), and an indication of where the type specimen or specimens are deposited for examination. The geographical location where a type specimen was originally found is known as its type locality. In the case of parasites, the term type host (or symbiotype) is used to indicate the host organism from which the type specimen was obtained.[12]

Zoological collections are maintained by universities and museums. Ensuring that types are kept in good condition and made available for examination by taxonomists are two important functions of such collections. And, while there is only one holotype designated, there can be other "type" specimens, the following of which are formally defined:

Holotype

[edit]When a single specimen is clearly designated in the original description, this specimen is known as the holotype of that species.[13] The holotype is typically placed in a major museum, or similar well-known public collection, so that it is freely available for later examination by other biologists.

Paratype

[edit]When the original description designated a holotype, there may be additional specimens that the author designates as additional representatives of the same species, termed paratypes. These are not name-bearing types.[citation needed]

Allotype

[edit]An allotype is a specimen of the opposite sex to the holotype, designated from among paratypes. The word was also formerly used for a specimen that shows features not seen in the holotype of a fossil.[14] The term is not regulated by the ICZN.[citation needed]

Neotype

[edit]A neotype is a specimen later selected to serve as the single type specimen when an original holotype has been lost or destroyed or where the original author never cited a specimen.

Syntype

[edit]A syntype is any one of two or more specimens that is listed in a species description where no holotype was designated; historically, syntypes were often explicitly designated as such, and under the present ICZN this is a requirement, but modern attempts to publish species description based on syntypes are generally frowned upon by practicing taxonomists, and most are gradually being replaced by lectotypes. Those that still exist are still considered name-bearing types.[citation needed]

Lectotype

[edit]A lectotype is a specimen later selected to serve as the single type specimen for species originally described from a set of syntypes. In zoology, a lectotype is a kind of name-bearing type. When a species was originally described on the basis of a name-bearing type consisting of multiple specimens, one of those may be designated as the lectotype. Having a single name-bearing type reduces the potential for confusion, especially considering that it is not uncommon for a series of syntypes to contain specimens of more than one species.

Formally, Carl Linnaeus is the lectotype for Homo sapiens, designated in 1959.[15][16] He published the first book considered to be part of taxonomical nomenclature, the 10th edition of Systema Naturae, which included the first description of Homo sapiens and determined all valid syntypes for the species.[15] Crucially, in 1959, Professor William Stearne wrote in a passing remark on Linnaeus's contributions, "Linnaeus himself, must stand as the type of his Homo sapiens."[15][17] He justified his choice by noting that the specimen that Linnaeus, who wrote his own autobiography five times, had most studied was probably himself.[18] This sufficiently and correctly designated Linnaeus to be the lectotype for Homo sapiens.[15]

It has also been suggested that Edward Cope is the lectotype for Homo sapiens, based on the 1994 reporting by Louie Psihoyos of an unpublished proposal by Bob Bakker to do so.[15] However, this designation is invalid both because Edward Cope was not one of the specimens described in Systema Naturae 10th Ed., and therefore not being a syntype is not eligible, and because Stearne's designation in 1959 has seniority and invalidates future designations.[15]

Paralectotype

[edit]A paralectotype is any additional specimen from among a set of syntypes after a lectotype has been designated from among them. These are not name-bearing types.[19]

Hapantotype

[edit]A special case in protists where the type consists of two or more specimens of "directly related individuals" within a preparation medium such as a blood smear. The terms parahapantotype and lectohapantotype refer to type preparations additional to the hapantotype and designated by the describing author.[20] As with other type designations the use of the prefix "Neo-", such as Neohapantotype, is employed when a replacement for the original hapantotype is designated, or when an original description did not include a designated type specimen.[21]

Iconotype

[edit]An illustration on which a new species or subspecies was based. For instance, the Burmese python, Python bivittatus, is one of many species that are based on illustrations by Albertus Seba (1734).[22][23]

Ergatotype

[edit]An ergatotype is a specimen selected to represent a worker member in hymenopterans which have polymorphic castes.[14]

Hypotype

[edit]A hypotype is a specimen whose details have previously been published that is used in a supplementary figure or description of the species.[24]

Kleptotype

[edit]The term "kleptotype" informally refers to a type specimen or a part of it that has been stolen, or improperly relocated.[25][26][27][28]

Alternatives to preserved specimens

[edit]Type illustrations have also been used by zoologists, as in the case of the Réunion parakeet, which is known only from historical illustrations and descriptions.[29]: 24

Recently, some species have been described where the type specimen was released alive back into the wild, such as the Bulo Burti boubou (a bushshrike), described as Laniarius liberatus, in which the species description included DNA sequences from blood and feather samples. Assuming there is no future question as to the status of such a species, the absence of a type specimen does not invalidate the name, but it may be necessary for the future to designate a neotype for such a taxon, should any questions arise. However, in the case of the bushshrike, ornithologists have argued that the specimen was a rare and hitherto unknown color morph of a long-known species, using only the available blood and feather samples. While there is still some debate on the need to deposit actual killed individuals as type specimens, it can be observed that given proper vouchering and storage, tissue samples can be just as valuable should dispute about the validity of a species arise.[citation needed]

Formalisation of the type system

[edit]The various types listed above are necessary[citation needed] because many species were described one or two centuries ago, when a single type specimen, a holotype, was often not designated. Also, types were not always carefully preserved, and intervening events such as wars and fires have resulted in the destruction of the original type material. The validity of a species name often rests upon the availability of original type specimens; or, if the type cannot be found, or one has never existed, upon the clarity of the description.

The ICZN has existed only since 1961 when the first edition of the Code was published. The ICZN does not always demand a type specimen for the historical validity of a species, and many "type-less" species do exist. The current edition of the Code, Article 75.3, prohibits the designation of a neotype unless there is "an exceptional need" for "clarifying the taxonomic status" of a species (Article 75.2).

There are many other permutations and variations on terms using the suffix "-type" (e.g., allotype, cotype, topotype, generitype, isotype, isoneotype, isolectotype, etc.) but these are not formally regulated by the Code, and a great many are obsolete and/or idiosyncratic. However, some of these categories can potentially apply to genuine type specimens, such as a neotype; e.g., isotypic/topotypic specimens are preferred to other specimens, when they are available at the time a neotype is chosen (because they are from the same time and/or place as the original type).[citation needed] A topotype is a specimen that was obtained from the same location that the original type specimen came from.[30]

The term fixation is used by the Code for the declaration of a name-bearing type, whether by original or subsequent designation.[citation needed]

Type species

[edit]

Each genus must have a designated type species (the term "genotype" was once used for this but has been abandoned because the word has become much better known as the term for a different concept in genetics). The description of a genus is usually based primarily on its type species, modified and expanded by the features of other included species. The generic name is permanently associated with the name-bearing type of its type species.[citation needed]

Ideally, a type species best exemplifies the essential characteristics of the genus to which it belongs, but this is subjective and, ultimately, technically irrelevant, as it is not a requirement of the Code. If the type species proves, upon closer examination, to belong to a pre-existing genus (a common occurrence), then all of the constituent species must be either moved into the pre-existing genus or disassociated from the original type species and given a new generic name; the old generic name passes into synonymy and is abandoned unless there is a pressing need to make an exception (decided case-by-case, via petition to the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature).[citation needed]

Type genus

[edit]A type genus is a genus from which the name of a family or subfamily is formed. As with type species, the type genus is not necessarily the most representative but is usually the earliest described, largest or best-known genus. It is not uncommon for the name of a family to be based upon the name of a type genus that has passed into synonymy; the family name does not need to be changed in such a situation.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Archetype

- Glossary of scientific naming

- Nomen dubium (zoology)

- Nomen nudum

- Genetypes – genetic sequence data from type specimens

- Pathotype – a type of intrasubspecific taxon of pathogenic bacteria

- Principle of typification

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Hitchcock, A.S. (1921), "The Type Concept in Systematic Botany", American Journal of Botany, 8 (5): 251–255, doi:10.2307/2434993, JSTOR 2434993

- ^ a b Nicholson, Dan H. "Botanical nomenclature, types, & standard reference works". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Department of Botany. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ^ Marshall, Stephen A.; Evenhuis, Neal L. (2015). "New species without dead bodies: a case for photo-based descriptions, illustrated by a striking new species of Marleyimyia Hesse (Diptera, Bombyliidae) from South Africa". ZooKeys (525): 117–127. Bibcode:2015ZooK..525..117M. doi:10.3897/zookeys.525.6143. ISSN 1313-2970. PMC 4607853. PMID 26487819.

- ^ "The Code Online | International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature". www.iczn.org. Retrieved 23 October 2025.

- ^ Lapage, S. P.; Sneath, P. H. A.; Lessel, E. F.; Skerman, V. B. D.; Seeliger, H. P. R.; Clark, W. A. (1992), "Rules of Nomenclature with Recommendations", International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria: Bacteriological Code, 1990 Revision, ASM Press, retrieved 23 October 2025

- ^ International Botanical Congress; Turland, Nicholas J.; Wiersema, John H.; Barrie, Fred R.; Gandhi, Kanchi N.; Gravendyck, Julia; Greuter, Werner; Hawksworth, David L.; Herendeen, Patrick S. (2025). International Code of Nomenclature for Algae, Fungi, and Plants. University of Chicago Press. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226839479.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-226-84199-1.

- ^ "Plant names – a basic introduction". Australian National Botanic Gardens, Centre for Australian National Biodiversity Research. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ^ de Candolle, A.P. (1867). Lois de la nomenclature botanique adoptées par le Congrès International de Botanique tenu à Paris en août 1867 suivies d'une deuxième édition de l'introduction historique et du commentaire qui accompagnaient la rédaction préparatoire présentée à la congrès. Genève et Bale: J.-B. Baillière et fils.

- ^ Weddell (1868). "Laws of Botanical Nomenclature adopted by the International Botanical Congress held at Paris in August 1867; together with an Historical Introduction and Commentary by Alphonse de Candolle, Translated from the French; Reprinted from the English translation published by L. Reeve and Co., London, 1868 (with three-page commentary by Asa Gray)". The American Journal of Science and Arts. Series II, Volume 46 (63–74, 75–77).

- ^ Crépin, F. (1886). "Rosa Synstylae: études sur les roses de la section Synstyleés". Bulletin de la Société Royale de Botanique de Belgique. 25 (2: Comptes-redus des séances de la Société Royale de Botanique de Belgique): 163–217.

- ^ a b McNeill, J.; Barrie, F.R.; Buck, W.R.; Demoulin, V.; Greuter, W.; Hawksworth, D.L.; Herendeen, P.S.; Knapp, S.; Marhold, K.; Prado, J.; Prud'homme Van Reine, W.F.; Smith, G.F.; Wiersema, J.H.; Turland, N.J. (2012). International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Melbourne Code) adopted by the Eighteenth International Botanical Congress Melbourne, Australia, July 2011. Vol. Regnum Vegetabile 154. A.R.G. Gantner Verlag KG. ISBN 978-3-87429-425-6.

- ^ Frey, Jennifer K.; Yates, Terry L.; Duszynski, Donald W.; Gannon, William L. & Gardner, Scott L. (1992). "Designation and Curatorial Management of Type Host Specimens (Symbiotypes) for New Parasite Species". The Journal of Parasitology. 78 (5): 930–993. doi:10.2307/3283335. JSTOR 3283335. S2CID 82003952.

- ^ "The Code Online | International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature". www.iczn.org.

- ^ a b Hawksworth, D.L. (2010). Terms Used in Bionomenclature. The naming of organisms (and plant communities). Copenhagen: Global Biodiversity Information Facility. p. 216. ISBN 978-87-92020-09-3.

- ^ a b c d e f "Who is the type of Homo sapiens?". International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ^ Spamer, Earle E. (1999). "Know Thyself: Responsible Science and the Lectotype of Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 149: 109–114. ISSN 0097-3157. JSTOR 4065043.

- ^ Stearn, W. T. (1 March 1959). "The Background of Linnaeus's Contributions to the Nomenclature and Methods of Systematic Biology". Systematic Biology. 8 (1): 4–22. doi:10.2307/sysbio/8.1.4. ISSN 1063-5157.

- ^ Spamer, Earle E. (1999). "Know Thyself: Responsible Science and the Lectotype of Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 149: 109–114. ISSN 0097-3157. JSTOR 4065043.

- ^ Hansen, Hans V.; Seberg, Ole (1984). "Paralectotype, a new type term in botany". Taxon. 33 (4): 707–711. Bibcode:1984Taxon..33..707H. doi:10.2307/1220790. JSTOR 1220790.

- ^ Bishop, M. A. W. (1989). "introduction". A taxonomic study of the Haemoproteidae (Apicomplexa: Haemosporina) of the Avian order Strigiformes (PDF) (Doctorate thesis). Memorial University of Newfound land. p. 3. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ Peirce, M. A.; Bennett, G. F. (1992). "Neohapantotype and paraneohapantotypes of Haemoproteus passeris Kruse, 1890". Journal of Natural History. 26 (3): 689–690. Bibcode:1992JNatH..26..689P. doi:10.1080/00222939200770431.

- ^ Seba, Albertus (1734). Locupletissimi Rerum naturalium Thesauri accurata Descriptio, et Iconibus artificiosissimus Expressio, per universam Physices Historiam. Opus, cui in hoc Rerum Genere, nullum par exstitit. Amsterdam: Janssonio-Waesbergios.

- ^ Bauer, Aaron M. (2002). "Albertus Seba, Cabinet of Natural Curiosities. The Complete Plates in Colour, 1734–1765. 2001". International Society for the History and Bibliography of Herpetology. 3.

- ^ "Compendium of Types". University of Basel.

- ^ Baker, N. T., & Timm, R. M. (1976). "Modern type concepts in entomology." Journal of the New York Entomological Society, 201–205.

- ^ Glime, J. M., & Wagner, D. H. (2013). "Herbarium methods and exchanges."

- ^ Kleptotype. (n.d.). Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved November 21, 2022, from https://en_ichthyology.en-academic.com/9763/kleptotype

- ^ "Terms Used in Bionomenclature: The Naming of Organisms and Plant Communities : Including Terms Used in Botanical, Cultivated Plant, Phylogenetic, Phytosociological, Prokaryote (bacteriological), Virus, and Zoological Nomenclature." (2010). United Kingdom: Global Biodiversity Information Facility.

- ^ Hume, Julian Pender (25 June 2007). "Reappraisal of the parrots (Aves: Psittacidae) from the Mascarene Islands, with comments on their ecology, morphology, and affinities" (PDF). Zootaxa. 1513 (1513): 1–76. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1513.1.1. ISSN 1175-5334. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ "Topotype Definition & Meaning". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

External links

[edit]- ICZN Code: International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, the official website

- Fishbase Glossary section (archived)

- A compendium of terms (archived)

- Zoological Type Nomenclature (Evenhuis) Archived 3 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine (PDF)

- Gruff, S. C.; Hodge, K. T. "What is a type specimen?". Cornell Plant Pathology Herbarium. Retrieved 24 February 2025.

.jpg/250px-Marocaster_coronatus_MHNT.PAL.2010.2.2_(Close_up).jpg)

.jpg/2000px-Marocaster_coronatus_MHNT.PAL.2010.2.2_(Close_up).jpg)