Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

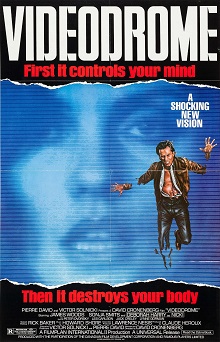

Videodrome

View on Wikipedia

| Videodrome | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | David Cronenberg |

| Written by | David Cronenberg |

| Produced by | Claude Héroux |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Mark Irwin |

| Edited by | Ronald Sanders |

| Music by | Howard Shore |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 89 minutes[1] |

| Country | Canada |

| Language | English |

| Budget | CAD$5.9 million |

| Box office | $2.1 million[2] |

Videodrome is a 1983 Canadian science fiction body horror film written and directed by David Cronenberg and starring James Woods, Sonja Smits, and Debbie Harry. Set in Toronto during the early 1980s, it follows the CEO of a small UHF television station who stumbles upon a broadcast signal of snuff films. Layers of deception and mind-control conspiracy unfold as he attempts to uncover the signal's source, complicated by increasingly intense hallucinations that cause him to lose his grip on reality.

Distributed by Universal Pictures, Videodrome was the first film by Cronenberg to gain backing from any major Hollywood studio. With the highest budget of any of his films at the time, the film was a box-office bomb, recouping only $2.1 million from a $5.9 million budget. The film received praise for the special makeup effects, Cronenberg's direction, Woods and Harry's performances, its "techno-surrealist" aesthetic, and its cryptic, psychosexual themes.[3] Cronenberg won the Best Direction award and was nominated for seven other awards at the 5th Genie Awards.[4]

Now considered a cult classic, the film has been cited as one of Cronenberg's best, and a key example of the body horror and science fiction horror genres.[5][6]

Plot

[edit]Max Renn is the president of CIVIC-TV, a Toronto UHF television station specializing in sensationalist programming. Harlan, the operator of CIVIC-TV's unauthorized satellite dish, shows Max Videodrome, a plotless show purportedly broadcast from Malaysia depicting victims being violently tortured and eventually murdered. Believing this to be the future of television, Max orders Harlan to begin unlicensed use of the show.

Nicki Brand, a sadomasochistic radio host[7] who becomes sexually involved with Max, is aroused by an episode of Videodrome.[8] Upon learning it is actually broadcast out of Pittsburgh, she goes to audition for the show but never returns. Max contacts Masha, a softcore pornographer, and asks her to help him investigate Videodrome. Masha informs Max that the footage is real and is the public "face" of a political movement, though Max remains skeptical, and that the enigmatic media theorist Brian O'Blivion knows about Videodrome.

Max tracks down O'Blivion to a homeless shelter where vagrants engage in marathon sessions of television viewing. He discovers that O'Blivion's daughter Bianca runs the mission, aiding her father's vision of a world where television replaces everyday life. Later, Max views a videotape of O'Blivion explaining that Videodrome is a socio-political battleground in which a war is being fought to control the minds of the people of North America. Max then hallucinates Nicki speaking directly to him, causing his television to undulate as he kisses the screen. Disturbed, Max returns to O'Blivion's shelter. Bianca tells him that Videodrome carries a broadcast signal that gives malignant brain tumors, which considers part of his vision, believing hallucinations are a higher form of reality. When O'Blivion found out it was to be used for malevolent purposes, he attempted to stop his partners, only to be killed by his own invention. In the year before his death, O'Blivion recorded thousands of videos, which now form the basis of his television appearances.

Later that night, Max hallucinates placing his handgun in a slit in his abdomen. He is contacted by Videodrome's producer, Barry Convex of the Spectacular Optical Corporation, an eyeglasses company that acts as a front for an arms company. Convex uses a device to record Max's hallucinations. Max envisions himself on the Videodrome set whipping Nicki, whose image then transforms into that of Masha. Max then wakes up at home to find Masha's corpse in his bed. He frantically calls Harlan to photograph the body as evidence, but, shortly after he arrives, her body is gone.

Wanting to see the latest Videodrome broadcast, Max meets Harlan at his studio. Harlan reveals that he has been working with Convex to recruit Max to their cause. They aim to end North America's cultural decay by using Videodrome to kill anyone too obsessed with sex and violence. Convex then inserts a brainwashing Betamax tape into Max's torso. Under Convex's influence, Max kills his colleagues at CIVIC-TV. He attempts to kill Bianca, who stops him by showing him a videotape of Nicki's murder on the Videodrome set. Bianca then "reprograms" Max to her father's cause: "Death to Videodrome. Long live the new flesh." Under her orders, he kills Harlan, whose hand transforms into a stielhandgranate after he inserts it into Max's torso slit and explodes, and Convex, whose body erupts into massive tumors and tears itself apart after Max shoots him with a gun fused to his hand.

Now wanted for murder, Max takes refuge on a derelict boat in the Port Lands. Appearing to him on television, Nicki tells him he has weakened Videodrome, but to defeat it, he must "leave the old flesh" and ascend to the next level. The television shows an image of Max shooting himself in the head, which causes the set to explode. Reenacting what he has just seen, Max utters the words "Long live the new flesh" and shoots himself.

Cast

[edit]- James Woods as Max Renn

- Debbie Harry as Nicki Brand

- Sonja Smits as Bianca O'Blivion

- Peter Dvorsky as Harlan

- Leslie Carlson as Barry Convex

- Jack Creley as Dr. Brian O'Blivion

- Lynne Gorman as Masha

- Julie Khaner as Bridey James

- David Bolt as Raphael

- Reiner Schwarz as Moses

- Lally Cadeau as Rena King

- King Cosmos as Brolley

- Harvey Chao as Shinji Kuraki

- David Tsubouchi as Hiro Nakamura

- Kay Hawtrey as Matron

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]The basis for Videodrome came from David Cronenberg's childhood. Cronenberg used to pick up American television signals from Buffalo, New York, late at night after Canadian stations had gone off the air, and worry he might see something disturbing not meant for public consumption.[9] As Cronenberg explained, "I've always been interested in dark things and other people's fascinations with dark things. Plus, the idea of people locking themselves in a room and turning a key on a television set so that they can watch something extremely dark, and by doing that, allowing themselves to explore their fascinations."[10] Cronenberg watched Marshall McLuhan, on whom O'Blivion was based, and McLuhan later taught at the University of Toronto while Cronenberg was a student there, although he never took any of McLuhan's classes.[11][12]

Cronenberg's first exploration of themes of the branding of sex and violence and media impacting people's reality was writing a treatment titled Network of Blood in the early 1970s; its premise was a worker for an independent television company (who would become Max Renn in Videodrome) unintentionally finding, in the filmmaker's words, "a private television network subscribed to by strange, wealthy people who were willing to pay to see bizarre things."[10] He later planned the story to be told from the main character's first-person perspective, showcasing a duality between how insane he looks to other people and how he himself perceives a different reality in his head.[10] Concepts similar to Network of Blood's were further explored in a 1977 episode of the CBC Television series Peep Show Cronenberg directed, named "The Victim."[10] The film's fictional station CIVIC-TV was modeled on the real-life Toronto television station CITY-TV, which was known for broadcasting pornographic content and violent films in its late-night programming bloc The Baby Blue Movie.[13][14]

Victor Snolicki, Dick Schouten, and Pierre David of Vision 4, a company taking advantage of Canada's tax shelter policies, aided Cronenberg in the film's financing.[15] Vision 4 dissolved after Schouten's death and reorganized into Filmplan International which funded Scanners.[16] Solnicki, David, and Claude Héroux formed Filmplan II which gave financial backing to Videodrome. This was the last film Cronenberg made under Canada's film tax shelter policy.[17]

Cronenberg's increased reputation made it easier for his projects to get produced, leading to the film's $5.5 million budget, more interest from studios and producers, and a larger number of interested actors to choose from.[18] After the box office success of Scanners, Cronenberg turned down the chance of directing Return of the Jedi, having had no desire to direct material produced by other filmmakers.[19] Cronenberg met with David in Montreal to discuss ideas for a new film, with the former pitching two ideas, one of them being Videodrome.[20]

Cronenberg started writing the first draft of Videodrome in January 1981, and, as with first drafts of Cronenberg's prior projects, included many parts not featured in the final cut to make it more acceptable for audiences; this included Renn having an explosive grenade as a hand after he chops off his flesh gun during a hallucination, Renn and Nicki melting, via a kiss, into an object that then melts an on-looker, and five other characters besides Barry also dying of cancer.[18] Cronenberg admits that he was worried that the project would be rejected by Filmplan due to the excessive violent content of an early draft, but it was approved, with Claude Héroux joking that the movie would get a triple X rating.[20][17] Although talent for the film was attracted using the first draft, alterations were made constantly from pre-production to post-production.[18]

Accumulation of the cast and crew started in the summer of 1981 in Toronto, with most of the supporting actors being local performers of the city.[18] Videodrome's three producers, David, Claude Héroux and Victor Solnicki, suggested James Woods for the role of Max Renn; they unsuccessfully tried to attach him to another film they produced, Models (1982).[18] Woods was a fan of Rabid (1977) and Scanners, and met Cronenberg in Beverly Hills for the part; Cronenberg liked the fact that Woods was very articulate in terms of delivery,[9] and Woods appreciated the filmmaker's oddball style as well as being a "good controversialist" with "a lot of power."[18] Cronenberg doubled for Woods in the scene where Max puts on the Videodrome helmet since the actor was afraid of getting electrocuted.[9] Co-star Debbie Harry was recommended by David, and Cronenberg cast her after viewing her two times in Union City (1980) and a Toronto audition.[18] She had never had such a large part before, and said that the more experienced Woods gave her a number of helpful suggestions.[21]

Filming

[edit]The film was shot in Toronto from October 27 to December 23, 1981, on a budget of $5,952,000 (equivalent to $18,890,085 in 2023), with the financing equally coming from Canada and the United States. 50% of the film's budget came from Universal.[22] The initial week of filming was devoted to videotaping various monitor inserts. These included the television monologues of Professor Brian O'Blivion, as well as the Videodrome torture scenes and the soft-core pornographic programs Samurai Dreams and Apollo & Dionysus.[23] The video camera used for the monitor scenes was a Hitachi SK-91.[24] The film's cinematography was handled by Mark Irwin, who was very uncomfortable with doing the monitor scenes; he was far more experienced with composing shots for regular film cameras than videotapes, disliked the flat television standards of lighting and color, and couldn't compose his shots privately as all of the film crew watched the monitors as the shots were being set up.[24] Cronenberg stated that Videodrome was the first time that he fired a crew worker due to an incident between a hairdresser and Harry.[25]

The Samurai Dreams short was filmed in half a day without any audio recorded at a rented spot at a Global TV studio in Toronto, and lasted five minutes longer than what ended up in the final film.[24]

Three different endings were filmed. The ending used in the final film, wherein Max shoots himself on the derelict ship, was James Woods' idea.[26] One of the initial intentions for the ending was to include an epilogue after the suicide, wherein Max, Bianca, and Nicki appear on the set of Videodrome. Bianca and Nicki are shown to have chest slits like Max, from which grotesque, mutated sex organs emerge.[26] Another ending featured an orgy between Bianca, Max, and Nicki after Max shoots himself and sex-organs were designed for the scene, but Cronenberg decided to remove the scene.[27]

Effects

[edit]Rick Baker, who worked on the effects of An American Werewolf in London, did the effects for the film. However, his desired six months of preparation was reduced to two months, and fewer effects were created due to a reduced budget.[28]

One of the scenes cut from the script showed Max and Nicki's faces melting together while kissing and going across the floor to a bystander's leg and melting him.[27]

Michael Lennick served as special video effects supervisor. To create the breathing effects of the television set that Max interacts with, Frank C. Carere used an air compressor with valves hooked to a piano keyboard that he himself operated.[citation needed] The undulating screen of the television set was created using a video projector and a sheet of rubbery dental dam. Baker stated that "I knew we would need a flexible material ... we tested with a weather balloon first, stretching it over a frame the size of a TV screen, and pushed a hand through it to see how far it stretched, and then we rear-projected on it."[23] Betamax videotape cassettes were used as items to be inserted into Max's stomach slit, because VHS cassettes were too large to fit the faux abdominal wound.[29] Woods found the stomach slit uncomfortable,[26] and after a long day of wearing it, vented, "I am not an actor anymore. I'm just the bearer of the slit!"[21] Baker's original concept for Max's flesh gun featured eyes, mouth and foreskin, which Cronenberg found to be "too graphic".[citation needed] The cancer effects caused by Max's flesh gun went through various tests, with some tests having the face of the victim being distorted through the use of solvents, but Baker decided against this upon learning that his mentor, Dick Smith, had recently used the same technique in Spasms.[23] Baker settled on having the cancer tumors burst out from the body of Barry Convex, with his crew operating a dummy underneath the set. Lennick devised effects such as having the image of the Videodrome television set distort whenever Max would whip it through the use of a device which he called the "Videodromer", and glitch and twitch effects related to Max's visions through the Videodrome helmet, but these effects were scrapped due to budget and time concerns.[23][9][30]

Music

[edit]An original score was composed for Videodrome by Cronenberg's close friend, Howard Shore.[31] The score was composed to follow Max Renn's descent into video hallucinations, starting out with dramatic orchestral music that increasingly incorporates, and eventually emphasizes, electronic instrumentation. To achieve this, Shore composed the entire score for an orchestra before programming it into a Synclavier II digital synthesizer. The rendered score, taken from the Synclavier II, was then recorded being played in tandem with a small string section.[32] The resulting sound was a subtle blend that often made it difficult to tell which sounds were real and which were synthesized.

The soundtrack was also released on vinyl by Varèse Sarabande, and was re-released on compact disc in 1998. The album itself is not just a straight copy of Shore's score, but a remix. Shore has commented that while there were small issues with some of the acoustic numbers, "on the whole I think they did very well".[32]

Editing

[edit]Cronenberg stated that the first test screening of a 72-75 minute cut of the film was "the most disastrous screening you can imagine". He and editor Ronald Sanders "thought we had cut it really tight, but it was totally incomprehensible that you didn't even know that Max Renn worked at Civic TV, I'd cut out all the footage that explained that".[33][34]

The MPAA requested multiple edits to the film. Bob Remy, the head of Universal Pictures, also suggested removing the scene in Samurai Dreams showing the dildo. Cronenberg was confused by Remy's suggestion as the "MPAA didn't even ask me to cut that. Why is he asking me to cut that". Thom Mount told Cronenberg that it was due to Remy having "a problem with cocks".[35] The film's runtime was 87 minutes and 18 seconds in Canada and the United States, but was 15 seconds longer in the international version.[22]

Cronenberg was critical of edits Universal Pictures performed on the film without request from the MPAA.[36]

Themes

[edit]According to Tim Lucas, Videodrome deals with "the impression of a sprawlingly technological world on our human senses; the fascination and horror of sex and violence; and the boundaries of reality and consciousness."[37]

Release

[edit]David was able to get Universal Pictures to finance and distribute the film based "on a one-page description," according to Cronenberg.[38] Videodrome was distributed by Universal Pictures in Canada and the United States, and by Les Films Mutuels in Quebec. It was released in six hundred theatres on February 4, 1983.[22]

Cronenberg stated that Sidney Sheinberg regretted giving the film a wide theatrical release rather than treating it as an art film. Around 900 prints of the film were distributed according to Cronenberg, and the film was only in theaters for a short amount of time. Cronenberg stated that Videodrome "wasn't an exploitation sell, and it wasn't an art sell. I don't know what it was."[39]

Reception

[edit]The film holds a 83% aggregate rating on Rotten Tomatoes, based on 59 reviews, with an average score of 7.5/10. Its consensus states, "Visually audacious, disorienting, and just plain weird, Videodrome's musings on technology, entertainment, and politics still feel fresh today."[40] It has been described as a "disturbing techno-surrealist film"[3] and "burningly intense, chaotic, indelibly surreal, absolutely like nothing else".[41] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 58 out of 100 based on 6 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews."[42] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "D+" on an A+ to F scale.[43]

Janet Maslin of The New York Times remarked on the film's "innovativeness", and praised Woods' performance as having a "sharply authentic edge".[44] Adam Smith of Empire gave the film 4 out of 5 possible stars, calling it a "perfect example" of body horror.[45] The staff of Variety wrote that the film "proves more fascinating than distancing", and commended the "stunning visual effects".[46] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post gave the film a negative review, calling it "simultaneously stupefying and boring".[8]

John Nubbin reviewed Videodrome for Different Worlds magazine and stated that "It is a top-notch thriller, a hard-hitting commentary which does not stop at the boundaries of reality, but plunges deep into nightmare to show a contemporary evil in the brightest possible light."[47]

C.J. Henderson reviewed Videodrome in The Space Gamer No. 63.[48] Henderson commented that "Despite the fact that Videodrome came and went faster than Superman and his bullet, it is still an excellent picture. It is a genre film of high caliber, posing a number of important questions."[48]

Christopher John reviewed Videodrome in Ares Magazine #14 and commented that "As usual, Cronenberg has pulled no punches in getting his message across. The movie is tight, and perfectly clear for anyone willing to watch the screen and think about what they are seeing."[49]

Trace Thurman of Bloody Disgusting listed it as one of eight "horror movies that were ahead of their time".[50][51] It was also selected as one of the "23 weirdest films of all time" by Total Film.[52] Nick Schager of Esquire ranked the film at number 10 on their list of "the 50 best horror movies of the 1980s".[53] The BFI includes it in their list of the greatest films of all time at joint 243rd place.[54]

Awards

[edit]The film won a number of awards upon its release. At the 1984 Brussels International Festival of Fantasy Film, it tied with Bloodbath at the House of Death for Best Science-Fiction Film, and Mark Irwin received a CSC Award for Best Cinematography in a Theatrical Feature. Videodrome was also nominated for eight Genie Awards, with David Cronenberg tying Bob Clark's A Christmas Story for Best Achievement in Direction.

It was the first Genie Award that Cronenberg won.[55]

Videodrome was named the 89th-most-essential film in history by the Toronto International Film Festival.[56]

Home media

[edit]Videodrome was released on VHS and DVD in the late 1990s by Universal Studios Home Entertainment, who also released the film on LaserDisc.

The film was released on DVD by the Criterion Collection on August 31, 2004, and their Blu-ray edition was released on December 7, 2010.[57][58] The Criterion Blu-ray features two commentary tracks, one with Cronenberg and cinematographer Mark Irwin, and the other with actors James Woods and Deborah Harry. Among the other special features are a documentary titled Forging the New Flesh; the soft-core video Samurai Dreams; the 2000 short film Camera; three trailers for Videodrome; and Fear on Film, which consists of an interview with Cronenberg, John Carpenter and John Landis, hosted by Mick Garris.[59]

In 2015, Arrow Films released the film on Blu-ray in Region B with further special features, including Cronenberg's short films Transfer (1966) and From the Drain (1967), as well as his feature films Stereo (1969) and Crimes of the Future (1970).[50]

Novelization

[edit]A novelization of Videodrome was released by Zebra Books alongside the movie in 1983. Though credited to "Jack Martin", the novel was, in fact, the work of horror novelist Dennis Etchison.[60] Cronenberg reportedly invited Etchison up to Toronto, where they discussed and clarified the story, allowing the novel to remain as close as possible to the actions in the film. There are some differences, however, such as the inclusion of the "bathtub sequence", a scene never filmed in which a television rises from Max Renn's bathtub like in Sandro Botticelli's The Birth of Venus.[61] This was the result of the lead time required to write the book, which left Etchison working with an earlier draft of the script than was used in the film.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Videodrome (18)". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ "Videodrome (1983) - Financial Informantion". The Numbers. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ a b Dinello, Daniel (2005). Technophobia!: science fiction visions of posthuman technology. University of Texas Press. p. 153. ISBN 0-292-70986-2.

- ^ "Videodrome". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- ^ "Videodrome". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- ^ "Videodrome (1983) – Deep Focus Review – Movie Reviews, Critical Essays, and Film Analysis". Deep Focus Review. February 2011. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- ^ Yvonne Tasker (2002). Fifty Contemporary Filmmakers. Psychology Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-415-18974-3. Archived from the original on July 15, 2024.

- ^ a b Gary Arnold (February 9, 1983). "The Jumbled Signal Of 'Videodrome'". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Cronenberg, David. Director's commentary, Videodrome, Criterion Collection DVD.

- ^ a b c d Lucas 1983, p. 34.

- ^ Cronenberg 2006, p. 65-66.

- ^ "The Video Word Made Flesh: 'Videodrome' and Marshall McLuhan". The Millions. April 19, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ Torontoist (November 21, 2012). "Reel Toronto: Videodrome". Torontoist. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ Perkins, Will (May 21, 2015). "Videodrome". Art of the Title. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ Rodley 1997, p. 75.

- ^ Rodley 1997, p. 85.

- ^ a b Rodley 1997, p. 93.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lucas 1983, p. 35.

- ^ Collis, Clark (September 28, 2018). "David Cronenberg Says Decision Not to Direct Return of the Jedi Was Met with 'Stunned Silence'". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- ^ a b Cronenberg on Cronenberg (1992)

- ^ a b Harry, Debbie; Simmons, Sylvie (2019). Face It. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 248–252. ISBN 978-0-06-074958-3.

- ^ a b c Turner 1987, p. 377-378.

- ^ a b c d Lucas, Tim (2004). "Medium Cruel: Reflections on Videodrome". Criterion.com. The Criterion Collection. Retrieved December 7, 2010.

- ^ a b c Lucas 1983, p. 36.

- ^ Cronenberg 2006, p. 66.

- ^ a b c Burns, William (August 28, 2014). "Ten Things You Might Not Know About ... Videodrome!". HorrorNewsNetwork.net. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ a b Rodley 1997, p. 97.

- ^ Rodley 1997, p. 96-97.

- ^ "10 Things You Didn't Know About... Videodrome". HMV. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ Videodrome, Criterion Collection Videodrome - Forging the New Flesh, documentary

- ^ Lucas, Tim (2008). Studies in the Horror Film: Videodrome. Lakewood, CO: Centipede Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-933618-28-9.

- ^ a b Lucas, Tim (2008). Studies in the Horror Film - Videodrome. Lakewood, CO: Centipede Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-933618-28-9.

- ^ Cronenberg 2006, p. 68.

- ^ Rodley 1997, p. 101.

- ^ Cronenberg 2006, p. 69.

- ^ Rodley 1997, p. 103.

- ^ Lucas 1983, p. 33.

- ^ Rodley 1997, p. 100.

- ^ Rodley 1997, p. 101-102.

- ^ "Videodrome". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ Beard & White 2002, p. 153.

- ^ "Videodrome Reviews". www.metacritic.com. Retrieved June 6, 2025.

- ^ Spokane Chronicle. Spokane Chronicle.

- ^ Janet Maslin (February 4, 1983). "'VIDEODROME,' LURID FANTASIES OF THE TUBE". The New York Times. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ Adam Smith (October 14, 2015). "Videodrome Review". Empire Online. Empire. Archived from the original on March 11, 2018. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ "Videodrome". Variety. December 31, 1982. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ Nubbin, John (March 1983). "Cinema News & Reviews". Different Worlds (27): 53.

- ^ a b Henderson, C.J. (May–June 1983). "Capsule Reviews". The Space Gamer (63). Steve Jackson Games: 39.

- ^ John, Christopher (Spring 1983). "Film". Ares Magazine (14). TSR, Inc.: 10–11.

- ^ a b Chris Coffel (August 27, 2015). "[Blu-ray Review] 'Videodrome' Gets the Ultimate Arrow Treatment". Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ Trace Thurman (July 30, 2015). "8 Horror Movies That Were Ahead Of Their Time". Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ "Total Film's 23 Weirdest Films of All Time on Lists of Bests". Listsofbests.com. April 6, 2007. Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- ^ Nick Schager (May 23, 2015). "The 50 Best Horror Films From the 1980s". Esquire. Archived from the original on August 9, 2017. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ "The Greatest Films of All Time".

- ^ Beard & White 2002, p. 152.

- ^ "2010 Press Releases - the Essential 100". Archived from the original on July 17, 2010. Retrieved July 24, 2010.

- ^ Jason Bovberg (August 30, 2004). "Videodrome: Criterion Collection". DVD Talk. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ Brad Brevet (December 7, 2010). "This Week On DVD and Blu-ray: December 7, 2010". ComingSoon.net. Archived from the original on March 12, 2018. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ Andre Dellamorte (December 15, 2010). "VIDEODROME Criterion Collection Blu-ray Review". Collider. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ ISFDB - Dennis Etchision Bibliography: Videodrome

- ^ Lucas, Tim (2008). Studies in the Horror Film - Videodrome. Lakewood, CO: Centipede Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-933618-28-9.

Works cited

[edit]- Beard, William; White, Jerry (2002). North of everything: English-Canadian Cinema Since 1980. The University of Alberta Press. ISBN 0-88864-398-5.

- Cronenberg, David (2006). David Cronenberg: Interviews with Serge Grünberg. Plexus Publishing. ISBN 0859653765.

- Lucas, Tim (December 1983). "Videodrome". Cinefantastique. pp. 32–49.

- Lucas, Tim. Studies in the Horror Film - Videodrome. Lakewood, CO: Centipede Press, 2008. ISBN 1-933618-28-0.

- Rodley, Chris, ed. (1997). Cronenberg on Cronenberg. Faber and Faber. ISBN 0571191371.

- Turner, D. John, ed. (1987). Canadian Feature Film Index: 1913-1985. Canadian Film Institute. ISBN 0660533642.

External links

[edit]- Videodrome at IMDb

- Videodrome at Box Office Mojo

- Videodrome at Rotten Tomatoes

- Videodrome at Metacritic

- Videodrome at the TCM Movie Database

- Videodrome review (archived) at InternalBleeding

- Videodrome: The Slithery Sense of Unreality an essay by Gary Indiana at the Criterion Collection

- understanding media - Videodrome, a list of academic texts about the film

_-_trailer.webm/232px--Videodrome_(1983)_-_trailer.webm.jpg)

_-_trailer.webm/632px--Videodrome_(1983)_-_trailer.webm.jpg)