Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

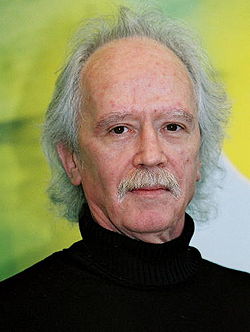

John Carpenter

View on Wikipedia

John Howard Carpenter (born January 16, 1948) is an American filmmaker, composer, and actor. Most commonly associated with horror, action, and science fiction films of the 1970s and 1980s, he is generally recognized as a master of the horror genre.[1] At the 2019 Cannes Film Festival, the French Directors' Guild gave him the Golden Coach Award and lauded him as "a creative genius of raw, fantastic, and spectacular emotions".[2][3] On April 3, 2025, he received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[4]

Key Information

Carpenter's early films included critical and commercial successes such as Halloween (1978), The Fog (1980), Escape from New York (1981), and Starman (1984). Though he has been acknowledged as an influential filmmaker, his other productions from the 1970s and the 1980s only later came to be considered cult classics; these include Dark Star (1974), Assault on Precinct 13 (1976), The Thing (1982), Christine (1983), Big Trouble in Little China (1986), Prince of Darkness (1987), They Live (1988), In the Mouth of Madness (1994), and Escape from L.A. (1996). He returned to the Halloween franchise as a composer and executive producer on Halloween (2018), Halloween Kills (2021), and Halloween Ends (2022).

Carpenter usually composes or co-composes the music in his films. He won a Saturn Award for Best Music for the soundtrack of Vampires (1998) and has released five studio albums: Lost Themes (2015), Lost Themes II (2016), Anthology: Movie Themes 1974–1998 (2017), Lost Themes III: Alive After Death (2021), and Lost Themes IV: Noir (2024). He also produces horror, science fiction, and children's comics through Storm King Comics, the publisher[5][6] founded by his wife, Sandy King, in 2013.[7]

Early life

[edit]John Howard Carpenter was born in Carthage, New York, on January 16, 1948, the son of Milton Jean (née Carter) and music professor Howard Ralph Carpenter.[8] In 1953, after his father accepted a job at Western Kentucky University, the family relocated to Bowling Green, Kentucky.[9] For much of his childhood, he and his family lived in a log cabin on the university's campus.[10][11] He was interested in films from an early age, particularly the westerns of Howard Hawks and John Ford, as well as 1950s low-budget horror films such as The Thing from Another World (which he would remake as The Thing in 1982) and high-budget sci-fi like Godzilla and Forbidden Planet.[12][13]

Carpenter began making short horror films with an 8 mm camera before he had even started high school.[14] Just before he turned 14 in 1962, he made a few major short films: Godzilla vs. Gorgo, featuring Godzilla and Gorgo via claymation, and the sci-fi western Terror from Space, starring the one-eyed creature from It Came from Outer Space.[15] He graduated from College High School, then enrolled at Western Kentucky University for two years as an English major and History minor.[10] With a desire to study filmmaking, which no university in Kentucky offered at the time, he moved to California upon transferring to the USC School of Cinematic Arts in 1968. He would ultimately drop out of school in his final semester in order to make his first feature film.[16]

Career

[edit]Early career: 1960s - 1970s

[edit]In a beginning film course at USC Cinema during 1969, Carpenter wrote and directed an eight-minute short film, Captain Voyeur. The film was rediscovered in the USC archives in 2011 and proved interesting because it revealed elements that would appear in his later film, Halloween (1978).[17]

The next year he collaborated with producer John Longenecker as co-writer, film editor, and music composer for The Resurrection of Broncho Billy (1970), which won an Academy Award for Best Live Action Short Film. The short film was enlarged to 35 mm, sixty prints were made, and the film was released theatrically by Universal Studios for two years in the United States and Canada.[18]

Carpenter's first major film as director, Dark Star (1974), was a science-fiction comedy that he co-wrote with Dan O'Bannon (who later went on to write Alien, borrowing freely from much of Dark Star). The film reportedly cost only $60,000 and was difficult to make as both Carpenter and O'Bannon completed the film by multitasking, with Carpenter doing the musical score as well as the writing, producing, and directing, while O'Bannon acted in the film and did the special effects (which caught the attention of George Lucas who hired him to work with the special effects for the film Star Wars). Carpenter received praise for his ability to make low-budget films.[19]

Carpenter's next film was Assault on Precinct 13 (1976), a low-budget thriller influenced by the films of Howard Hawks, particularly Rio Bravo. As with Dark Star, Carpenter was responsible for many aspects of the film's creation. He not only wrote, directed, and scored it, but also edited the film using the pseudonym "John T. Chance" (the name of John Wayne's character in Rio Bravo). Carpenter has said that he considers Assault on Precinct 13 to have been his first real film because it was the first film that he filmed on a schedule.[20] The film was the first time Carpenter worked with Debra Hill, who would collaborate with Carpenter on some of his most well-known films.

Carpenter assembled a main cast that consisted of experienced but relatively obscure actors. The two main actors were Austin Stoker, who had appeared previously in science fiction, disaster, and blaxploitation films, and Darwin Joston, who had worked primarily for television and had once been Carpenter's next-door neighbor.[21]

The film received a critical reassessment in the United States, where it is now generally regarded as one of the best exploitation films of the 1970s.[22]

Carpenter both wrote and directed the Lauren Hutton thriller Someone's Watching Me!. This television film is the tale of a single, working woman who, soon after arriving in L.A., discovers that she is being stalked.

Eyes of Laura Mars, a 1978 thriller featuring Faye Dunaway and Tommy Lee Jones and directed by Irvin Kershner, was adapted (in collaboration with David Zelag Goodman) from a spec script titled Eyes, written by Carpenter, and would become Carpenter's first major studio film of his career.

Halloween (1978) was a commercial success and helped develop the slasher genre. Originally an idea suggested by producer Irwin Yablans (titled The Babysitter Murders), who thought of a film about babysitters being menaced by a stalker, Carpenter took the idea and another suggestion from Yablans that it occur during Halloween and developed a story.[23] Carpenter said of the basic concept: "Halloween night. It has never been the theme in a film. My idea was to do an old haunted house film."[24]

Film director Bob Clark suggested in an interview released in 2005[25] that Carpenter had asked him for his own ideas for a sequel to his 1974 film Black Christmas (written by Roy Moore) that featured an unseen and motiveless killer murdering students in a university sorority house. As also stated in the 2009 documentary Clarkworld (written and directed by Clark's former production designer Deren Abram after Clark's tragic death in 2007), Carpenter directly asked Clark about his thoughts on developing the anonymous slasher in Black Christmas:

...I did a film about three years later, started a film with John Carpenter, it was his first film for Warner Bros. (which picked up 'Black Christmas'), he asked me if I was ever gonna do a sequel, and I said no. I was through with horror, I didn't come into the business to do just horror. He said, "Well, what would you do if you did do a sequel?" I said it would be the next year, and the guy would have actually been caught, escape from a mental institution, go back to the house, and they would start all over again. And I would call it 'Halloween'. The truth is John didn't copy 'Black Christmas', he wrote a script, directed the script, did the casting. 'Halloween' is his movie, and besides, the script came to him already titled anyway. He liked 'Black Christmas' and may have been influenced by it, but John Carpenter did not copy the idea. Fifteen other people had thought to do a movie called 'Halloween,' but the script came to John with that title on it.

— Bob Clark, 2005[25]

The film was written by Carpenter and Debra Hill with Carpenter stating that the music was inspired by both Dario Argento's Suspiria (which also influenced the film's slightly surreal color scheme) and William Friedkin's The Exorcist.[24]

Carpenter again worked with a relatively small budget, $300,000.[26] The budget was so small the actors provided their own costumes.[27] The film grossed more than $65 million initially, making it one of the most successful independent films of all time.[28]

Carpenter has described Halloween as "true crass exploitation. I decided to make a film I would love to have seen as a kid, full of cheap tricks like a haunted house at a fair where you walk down the corridor and things jump out at you".[29] The film has often been cited[by whom?] as an allegory on the virtue of sexual purity and the danger of casual sex, although Carpenter has explained that this was not his intent: "It has been suggested that I was making some kind of moral statement. Believe me, I'm not. In Halloween, I viewed the characters as simply normal teenagers."[23]

In addition to the film's critical and commercial success, Carpenter's self-composed "Halloween Theme" became recognizable apart from the film.[30]

In 1979, Carpenter began what was to be the first of several collaborations with actor Kurt Russell when he directed the television film Elvis.

Commercial successes: 1980s

[edit]Carpenter followed up the success of Halloween with The Fog (1980), a ghostly revenge tale (co-written by Hill) inspired by horror comics such as Tales from the Crypt[31] and by The Crawling Eye, a 1958 film about monsters hiding in clouds.[32]

Completing The Fog was an unusually difficult process for Carpenter. After viewing a rough cut of the film, he was dissatisfied with the result. For the only time in his filmmaking career, Carpenter had to devise a way to salvage a nearly finished film that did not meet his standards. In order to make the film more coherent and frightening, Carpenter filmed additional footage that included new scenes.[citation needed]

Despite production problems and mostly negative critical reception, The Fog was another commercial success for Carpenter. The film was made on a budget of $1,000,000,[33] but it grossed over $21,000,000 in the United States alone. Carpenter has said that The Fog is not his favorite film, although he considers it a "minor horror classic".[32]

Carpenter immediately followed The Fog with the science-fiction adventure Escape from New York (1981). Featuring several actors that Carpenter had collaborated with (Kurt Russell, Donald Pleasence, Adrienne Barbeau, Tom Atkins, Charles Cyphers, and Frank Doubleday) or would collaborate with again (Harry Dean Stanton), and other actors (Lee Van Cleef and Ernest Borgnine), it became both commercially successful (grossing more than $25 million) and critically acclaimed (with an 85% on Rotten Tomatoes).[34]

His next film, The Thing (1982), has high production values, including innovative special effects by Rob Bottin, special visual effects by matte artist Albert Whitlock, a score by Ennio Morricone and a cast including Russell and respected character actors such as Wilford Brimley, Richard Dysart, Charles Hallahan, Keith David, and Richard Masur. The Thing was distributed by Universal Pictures. Although Carpenter's film used the same source material as the 1951 Howard Hawks film, The Thing from Another World, it is more faithful to the John W. Campbell Jr. novella Who Goes There?, upon which both films were based. Moreover, unlike the Hawks film, The Thing was part of what Carpenter later called his "Apocalypse Trilogy", a trio of films (The Thing, Prince of Darkness, and In the Mouth of Madness) with bleak endings for the film's characters.[citation needed]

Being a graphic, sinister horror film,[35] In a 1999 interview, Carpenter said audiences rejected The Thing for its nihilistic, depressing viewpoint at a time when the United States was in the midst of a recession.[36] When it opened, it was competing against the critically and commercially successful E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial ($619 million), a family-friendly film released two weeks earlier that offered a more optimistic take on alien visitation.[37][38][39]

The impact on Carpenter was immediate – he lost the job of directing the 1984 science fiction horror film Firestarter because of The Thing's poor performance.[40] His previous success had gained him a multiple-film contract at Universal, but the studio opted to buy him out of it instead.[41] He continued making films afterward but lost confidence, and did not openly talk about The Thing's failure until a 1985 interview with Starlog, where he said, "I was called 'a pornographer of violence' ... I had no idea it would be received that way ... The Thing was just too strong for that time. I knew it was going to be strong, but I didn't think it would be too strong ... I didn't take the public's taste into consideration."[42]

While The Thing was not initially successful, it was able to find new audiences and appreciation on home video, and later on television.[43]

In the years following its release, critics and fans have reevaluated The Thing as a milestone of the horror genre.[44] A prescient review by Peter Nicholls in 1992, called The Thing "a black, memorable film [that] may yet be seen as a classic".[45] It has been called one of the best films directed by Carpenter.[46][47][48] John Kenneth Muir called it "Carpenter's most accomplished and underrated directorial effort",[49] and critic Matt Zoller Seitz said it "is one of the greatest and most elegantly constructed B-movies ever made".[50]Trace Thurman described it as one of the best films ever,[51] and in 2008, Empire magazine selected it as one of The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time,[52] at number 289, calling it "a peerless masterpiece of relentless suspense, retina-wrecking visual excess and outright, nihilistic terror".[53] It is now considered to be one of the greatest horror films ever made.[49][54]

Carpenter's next film, Christine, was the 1983 adaptation of the Stephen King novel of the same name. The story concerns a high-school nerd named Arnie Cunningham (Keith Gordon) who buys a junked 1958 Plymouth Fury which turns out to have supernatural powers. As Cunningham restores and rebuilds the car, he becomes unnaturally obsessed with it, with deadly consequences. Christine did respectable business upon its release and was received well by critics. He said he directed it because it was the only thing offered to him at the time.[55]

Starman (1984) was produced by Michael Douglas; the script was well received by Columbia Pictures, which chose it in preference to the script for E.T. and prompted Steven Spielberg to go to Universal Pictures. Douglas chose Carpenter to be the director because of his reputation as an action director who could also convey strong emotion.[56] Starman was reviewed favorably by the Los Angeles Times, New York Times, and LA Weekly, and described by Carpenter as a film he envisioned as a romantic comedy similar to It Happened One Night only with a space alien.[57][58] The film received Oscar and Golden Globe nominations for Jeff Bridges' portrayal of Starman and received a Golden Globe nomination for Best Musical Score for Jack Nitzsche.

After the financial failure of his big-budget action–comedy Big Trouble in Little China (1986), Carpenter struggled to get films financed. He resumed making lower budget films such as Prince of Darkness (1987), a film influenced by the BBC series Quatermass. Although some of the films from this time, such as They Live (1988) did develop a cult audience, he never again realized mass-market potential.[citation needed]

Later career: 1990s - 2000s

[edit]Carpenter's 1990s films, including Memoirs of an Invisible Man (1992) and Village of the Damned (1995), did not achieve the same initial commercial success of his earlier work. Carpenter made Body Bags, a television horror anthology film in collaboration with Tobe Hooper and In the Mouth of Madness (1995), a Lovecraftian homage that was not successful commercially or with critics,[59] but now has a cult following.[60] Escape from L.A. (1996), the sequel of the cult classic Escape from New York, received mixed reviews but has also gained a cult following since its release.[61][62] Vampires (1998) featured James Woods as the leader of a band of vampire hunters in league with the Catholic Church.[citation needed]

In 1998, Carpenter composed the soundtrack (titled "Earth/Air") for the video game Sentinel Returns, published for PC and PlayStation.[63]

In 2001, his film Ghosts of Mars was released but was not successful. During 2005, there were remakes of Assault on Precinct 13 and The Fog, the latter being produced by Carpenter himself, though in an interview he defined his involvement as, "I come in and say hello to everybody. Go home."[citation needed]

Carpenter served as director for a 2005 episode of Showtime's Masters of Horror television series, one of the 13 filmmakers involved in the first season. His episode, "Cigarette Burns", received generally positive reviews from critics and praise from Carpenter's fans. He later directed another original episode for the show's second season in 2006 titled "Pro-Life".[citation needed]

2010s: The Ward, focus on music and return to Halloween

[edit]The Ward, Carpenter's first film since Ghosts of Mars, premiered at Toronto International Film Festival on September 13, 2010, before a limited release in the United States in July 2011. It received generally poor reviews from critics and grossed only $5.3 million worldwide against an estimated $10 million budget. As of 2025, it is the most recent film he directed.[citation needed]

Carpenter narrated the video game F.E.A.R. 3, while also consulting on its storyline.[64] On October 10, 2010, Carpenter received the Lifetime Award from the Freak Show Horror Film Festival.[65]

On February 3, 2015, the indie label Sacred Bones Records released his album Lost Themes.[66] On October 19, 2015, All Tomorrow's Parties announced that Carpenter will be performing old and new compositions in London and Manchester, England.[67] In February 2016, Carpenter announced a sequel to Lost Themes titled Lost Themes II, which was released on April 15 that year.[68] He released his third studio album, titled Anthology: Movie Themes 1974–1998, on October 20, 2017.[69]

Carpenter returned, as executive producer, co-composer, and creative consultant, on the 11th entry of the Halloween film series, titled Halloween, released in October 2018. The film is a direct sequel to Carpenter's original film, breaking the continuity of earlier sequels. It was his first direct involvement with the franchise since 1982's Halloween III: Season of the Witch.[70]

2020s: Halloween sequels, Toxic Commando, Suburban Screams, and Hollywood Walk of Fame

[edit]

Carpenter worked as a composer and executive producer on the 2021 sequel Halloween Kills and 2022's follow-up Halloween Ends.[71]

During Summer Game Fest in June 2023, it was announced that Carpenter was collaborating with Focus Entertainment and Saber Interactive on the zombie first-person shooter video game Toxic Commando.[72] The game is scheduled to be released in 2026 on PlayStation 5, Xbox Series X/S, and Windows via Steam and the Epic Games Store.[73] Carpenter worked on the game's story and also composed its musical score.[74]

In October 2023, he directed an episode of the Peacock streaming series Suburban Screams while also composing the series theme music and serving as an executive producer.[75][76]

On December 8, 2024, Carpenter received a Career Achievement Award from the Los Angeles Film Critics Association.[77] On April 3, 2025, Carpenter received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[4]

In October 2025, Carpenter served as an executive producer on the horror anthology series John Carpenter Presents.[78]

Style and influences

[edit]Carpenter's films are characterized by minimalist lighting and photography, panoramic shots, use of steadicam, and scores he usually composes himself.[79] With a few exceptions,[a] he has scored all of his films (some of which he co-scored), most famously the themes from Halloween and Assault on Precinct 13. His music is generally synthesized with accompaniment from piano and atmospherics.[80]

Carpenter is known for his widescreen shot compositions and is an outspoken proponent of Panavision anamorphic cinematography. With some exceptions,[b] all of his films were shot in Panavision anamorphic format with a 2.39:1 aspect ratio, generally favoring wider focal lengths. The Ward was filmed in Super 35, the first time Carpenter has ever used that system. He has stated that he feels the 35 mm Panavision anamorphic format is "the best movie system there is" and prefers it to both digital and 3D.[81]

Film music and solo records

[edit]

In a 2016 interview, Carpenter stated that it was his father's work as a music teacher that first sparked an interest in him to make music.[82] This interest was to play a major role in his later career: he composed the music to most of his films, and the soundtrack to many of those became "cult" items for record collectors. A 21st-Century revival of his music is due in no small amount to the Death Waltz record company, which reissued several of his soundtracks, including Escape from New York, Halloween II, Halloween III: Season of the Witch, Assault on Precinct 13, They Live, Prince of Darkness, and The Fog.[83]

Carpenter was an early adopter of synthesizers, since his film debut Dark Star, when he used an EMS VCS3 synth. His soundtracks went on to influence electronic artists who followed,[84][85] but Carpenter himself admitted he had no particular interest in synthesizers other than that they provided a means to "sound big with just a keyboard". For many years he worked in partnership with musician Alan Howarth, who would realize his vision by working on the more technical aspects of recording, allowing Carpenter to focus on writing the music.[82]

The renewed interest in John Carpenter's music thanks to the Death Waltz reissues and Lost Themes albums prompted him to, for the first time ever, tour as a musician.[86] As of 2016[update], Carpenter was more focused on his music career than filmmaking, although he was involved in 2018's Halloween reboot, and its sequels.[87]

Carpenter narrates the documentary film The Rise of the Synths, which explores the origins and growth of the synthwave genre, and features numerous interviews with synthwave artists who cite him and other electronic pioneers such as Vangelis, Giorgio Moroder and Tangerine Dream as significant influences.[88][89] The retro-1980s synthwave band Gunship are featured in the film; Carpenter narrated the opening to their track entitled "Tech Noir".[90]

Carpenter is featured on the track "Destructive Field" on his godson Daniel Davies' album Signals, released February 28, 2020.[91]

His third solo album Lost Themes III: Alive After Death was launched on February 2, 2021. A new (digital) single was released on October 27, 2020, titled Weeping Ghost, followed in December 2020 by another new track from the forthcoming album, titled The Dead Walk.[92] Two tracks that also appear on the album, Skeleton and Unclear Spirit, were released in July 2020. On the album, Carpenter collaborated again with his son Cody and his godson Daniel Davies.[93][94] In August 2023, a fifth collaboration with Cody Carpenter and Daniel Davies was announced for Sacred Bones Records, titled Anthology II: Movie Themes 1976–1988, and was released on October 6, 2023.[95]

A fourth Lost Themes album was announced in March 2024, subtitled "Noir". It was again recorded in collaboration with Cody Carpenter and Daniel Davies. It was released on May 3 on Sacred Bones Records. The album was preceded by the single and official video "My Name is Death".[96][97][98]

Personal life

[edit]

Carpenter met actress Adrienne Barbeau on the set of his television film Someone's Watching Me! (1978). They married on January 1, 1979, and divorced in 1984. During their marriage, she appeared in his films The Fog and Escape from New York.[99] They have one son, Cody Carpenter (born May 7, 1984), who became a musician and composer. Cody's godfather is English-American musician Daniel Davies, whose own godfather is Carpenter.[100]

Carpenter married film producer Sandy King in 1990. She produced his films In the Mouth of Madness, Village of the Damned, Vampires, and Ghosts of Mars. She was earlier the script supervisor for Starman, Big Trouble in Little China, Prince of Darkness, and They Live, as well as an associate producer of the latter.[101] She co-created (with Thomas Ian Griffith)[102] the comic book series Asylum, with which Carpenter is involved.[103]

In an episode of Animal Planet's Animal Icons titled "It Came from Japan", Carpenter discussed his admiration for the original Godzilla film.[104] He also appreciates video games as art, and particularly likes the Sonic the Hedgehog games Sonic Unleashed and Sonic Mania,[105] as well as the F.E.A.R. series. He offered to narrate and help direct the cinematics for F.E.A.R. 3, ultimately serving as the game's narrator and consulting on its storyline.[106] He has also praised video games such as Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy and Fallout 76.[107][108] He has also expressed an interest in making a film based on Dead Space.[107][109]

Carpenter has called his political views "inconsistent" and has said that he is against authority figures while also in favor of big government, admitting that this set of views "doesn't make any sense". When asked if he considered himself a libertarian-liberal, he simply responded "kinda".[110] He has been an outspoken critic of Donald Trump and has blamed modern problems in the United States on unrestrained capitalism.[111]

Carpenter holds a commercial pilot's license and flies helicopters. He has included helicopters in his films, many of which feature him in a cameo role as a pilot.[citation needed]

Legacy

[edit]

Many of Carpenter's films have been re-released on DVD as special editions with numerous bonus features. Examples of such are: the collector's editions of Halloween, Escape from New York, Christine, The Thing, Assault on Precinct 13, Big Trouble In Little China, and The Fog. Some were re-issued with a new anamorphic widescreen transfer. In the UK, several of Carpenter's films have been released as DVD with audio commentary by Carpenter and his actors (They Live, with actor/wrestler Roddy Piper, Starman with actor Jeff Bridges, and Prince of Darkness with actor Peter Jason).[citation needed]

Carpenter is the subject of the documentary film John Carpenter: The Man and His Movies, and American Cinematheque's 2002 retrospective of his films. Moreover, during 2006, the United States Library of Congress deemed Halloween to be "culturally significant" and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry.[112]

During 2010, writer and actor Mark Gatiss interviewed Carpenter about his career and films for his BBC documentary series A History of Horror. Carpenter appears in all three episodes of the series.[113] He was also interviewed by Robert Rodriguez for his The Director's Chair series on El Rey Network.

Filmmakers that have been influenced by Carpenter include: James Cameron,[114] Quentin Tarantino,[115][116] Guillermo del Toro,[117] Robert Rodriguez,[118][119] James Wan,[120] Edgar Wright,[121][122][123] Danny Boyle,[124] Nicolas Winding Refn,[125][126][127][128] Adam Wingard,[129][130][131] Neil Marshall,[132][133] Michael Dougherty,[134][135] Ben Wheatley,[136] Jeff Nichols,[137][138] Bong Joon-ho,[139][140][141][142] James Gunn,[143] Mike Flanagan,[144] David Robert Mitchell,[145][146] The Duffer Brothers,[147][148] Jeremy Saulnier,[129][149][150] Trey Edward Shults,[151][152] Drew Goddard,[153][154] David F. Sandberg,[155] James DeMonaco,[129] Adam Green,[156] Ted Geoghegan,[157][158] Keith Gordon,[159][160] Brian Patrick Butler,[161][162] Jack Thomas Smith,[163] and Marvin Kren.[164][165][166][167] The video game Dead Space 3 is said to be influenced by Carpenter's The Thing, The Fog, and Halloween, and Carpenter has stated that he would be enthusiastic to adapt that series into a feature film.[168] Specific films influenced by Carpenter's include Sean S. Cunningham's Friday the 13th, which was inspired by the success of Halloween,[169] Tarantino's The Hateful Eight, which was heavily influenced by The Thing,[115] Wingard's The Guest, which was inspired by Michael Myers[130] and influenced by Halloween III: Season of the Witch's music,[129][131] Nichols' Midnight Special, which is said to have used Starman as a reference point,[137][138] and Kren's Blood Glacier, which is said to be a homage to or recreation of The Thing.[164]

Hans Zimmer cited Carpenter as an influence on his compositions.[170] The 2016 film The Void is considered by many critics and fans to be heavily influenced by several of Carpenter's films.[171]

Filmography

[edit]| Year | Title | Distributor |

|---|---|---|

| 1974 | Dark Star | Bryanston Distributing Company |

| 1976 | Assault on Precinct 13 | Turtle Releasing Organization |

| 1978 | Halloween | Compass International Pictures/Aquarius Releasing |

| 1980 | The Fog | AVCO Embassy Pictures |

| 1981 | Escape from New York | |

| 1982 | The Thing | Universal Pictures |

| 1983 | Christine | Columbia Pictures |

| 1984 | Starman | |

| 1986 | Big Trouble in Little China | 20th Century Fox |

| 1987 | Prince of Darkness | Universal Pictures/Carolco Pictures |

| 1988 | They Live | |

| 1992 | Memoirs of an Invisible Man | Warner Bros. |

| 1994 | In the Mouth of Madness | New Line Cinema |

| 1995 | Village of the Damned | Universal Pictures |

| 1996 | Escape from L.A. | Paramount Pictures |

| 1998 | Vampires | Sony Pictures Releasing/Columbia Pictures |

| 2001 | Ghosts of Mars | Sony Pictures Releasing/Screen Gems |

| 2010 | The Ward | ARC Entertainment/XLrator Media |

Recurring collaborators

[edit]Work Collaborator

|

1974 | 1976 | 1978 | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | 1984 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1998 | 2001 | 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adrienne Barbeau | (voice) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Robert Carradine | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Nick Castle | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Dean Cundey | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Jamie Lee Curtis | (voice) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Charles Cyphers | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Keith David | |||||||||||||||||||||

| George Buck Flower | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Pam Grier | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Marjean Holden | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Alan Howarth | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Jeff Imada | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Peter Jason | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Gary B. Kibbe | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Al Leong | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Nancy Loomis | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Sam Neill | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Robert Phalen | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Donald Pleasence | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Marion Rothman | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Kurt Russell | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Harry Dean Stanton | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Shirley Walker | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Tommy Lee Wallace | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Victor Wong | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Dennis Dun | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Frank Doubleday | |||||||||||||||||||||

Discography

[edit]Albums

[edit]| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1979 | Halloween | soundtrack to the 1978 film |

| 1980 | Dark Star | soundtrack to the 1974 film |

| 1981 | Escape from New York | soundtrack to the 1981 film, with Alan Howarth |

| Halloween II | ||

| 1982 | Halloween III: Season of the Witch | soundtrack to the 1982 film, with Alan Howarth |

| 1984 | The Fog | soundtrack to the 1980 film |

| 1986 | Big Trouble in Little China | soundtrack to the 1986 film, with Alan Howarth |

| 1987 | Prince of Darkness | soundtrack to the 1987 film, with Alan Howarth |

| 1988 | They Live | soundtrack to the 1988 film, with Alan Howarth |

| 1989 | Christine | soundtrack to the 1983 film, with Alan Howarth |

| 1993 | Body Bags | soundtrack to the 1993 TV movie, with Jim Lang |

| 1995 | In the Mouth of Madness | soundtrack to the 1994 film, with Jim Lang |

| Village of the Damned | soundtrack to the 1995 film, with Dave Davies | |

| 1996 | Escape from L.A. | soundtrack to the 1996 film, with Shirley Walker |

| 1998 | Vampires | soundtrack to the 1998 film |

| 2001 | Ghosts of Mars | soundtrack to the 2001 film |

| 2003 | Assault on Precinct 13 | soundtrack to the 1976 film |

| 2015 | Lost Themes | co-written with session musicians Cody Carpenter & Daniel Davies |

| 2016 | Lost Themes II | |

| 2018 | Halloween | soundtrack to the 2018 film, with Cody Carpenter & Daniel Davies |

| 2021 | Lost Themes III: Alive After Death | co-written with session musicians Cody Carpenter & Daniel Davies |

| Halloween Kills | soundtrack to the 2021 film, with Cody Carpenter & Daniel Davies | |

| 2022 | Firestarter | soundtrack to the 2022 film, with Cody Carpenter & Daniel Davies |

| Halloween Ends | ||

| 2024 | Lost Themes IV: Noir | co-written with session musicians Cody Carpenter & Daniel Davies |

| 2025 | Lost Themes: 10th Anniversary Expanded Edition | co-written with session musicians Cody Carpenter & Daniel Davies |

Remix albums

[edit]| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Lost Themes Remixed | Remixes of Lost Themes |

EPs

[edit]| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Classic Themes Redux EP | Followed by Anthology: Movie Themes 1974–1998 |

| 2020 | Lost Cues: The Thing | Newly recorded soundtrack for the 1982 film |

Singles

[edit]| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2020 | "Skeleton" b/w "Unclean Spirit" | non-album single[172] |

Compilation albums

[edit]| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2017 | Anthology: Movie Themes 1974–1998 | Rerecorded film scores, preceded in 2016 by EP Classic Themes Redux |

| 2023 | Anthology II: Movie Themes 1976–1988 |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Jason Zinoman (June 24, 2011). "A Lord of Fright Reclaims His Dark Domain". The New York Times.

- ^ Chu, Henry (March 28, 2019). "Cannes: John Carpenter to Receive Golden Coach Award at Directors' Fortnight". Variety. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- ^ Cotton, Johnny (May 15, 2019). "Cult horror director John Carpenter honored at Cannes". Reuters. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- ^ a b DiVincenzo, Alex (March 21, 2025). "John Carpenter to Receive His Hollywood Walk of Fame Star in April". Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved March 23, 2025.

- ^ Skye Fadroski, Kelli (September 26, 2023). "How Sandy and John Carpenter will celebrate 10 years of terror in graphic novels". Los Angeles Daily News. Archived from the original on October 11, 2025. Retrieved October 11, 2025.

- ^ "About Us". Storm King Comics. Archived from the original on October 11, 2025. Retrieved October 11, 2025.

- ^ "About Storm King". Storm King Comics. Archived from the original on October 11, 2025. Retrieved October 11, 2025.

- ^ "John Carpenter Biography (1948–)". Film Reference.

- ^ Kleber, John E., ed. (1992). "Carpenter, John Howard". The Kentucky Encyclopedia. Associate editors: Thomas D. Clark, Lowell H. Harrison, and James C. Klotter. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1772-0.

- ^ a b "John Carpenter Biography". Bowling Green Area Convention & Visitors Bureau.

- ^ "Pioneer Log Cabin". Kentucky Folklife Program. May 10, 2017.

- ^ Sokol, Tony (November 2, 2022). "John Carpenter: What Hollywood Doesn't Get About Godzilla". Den of Geek. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- ^ Lanzagorta, Marco (March 1, 2003). "John Carpenter". Senses of Cinema. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ "John Carpenter - Biography". AMC TV. Archived from the original on March 12, 2007.

- ^ Clarke, Frederick S. (December 12, 1979). "Carpenter's boyhood dream was making horror films". Cinefantastique. 9: 3.

- ^ "John CarpenterBiography, Movies, Albums, & Facts". Britannica . August 19, 2025. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- ^ Barnes, Mike (October 26, 2011). "'Halloween' Director John Carpenter's First Student Film Unearthed". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Phillips, William H. (1999). Writing Short Scripts: Second Edition. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. pp. 126–127. ISBN 0-8156-2802-1.

- ^ "John Carpenter: Press: London Times: 3–8–78". TheOfficialJohnCarpenter.com. March 8, 1978. Archived from the original on December 10, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ Goldwasser, Dan (May 9, 2012). "John Carpenter – Interview". Soundtrack.net. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ Q & A session with John Carpenter and Austin Stoker at American Cinematheque's 2002 John Carpenter retrospective, in the Assault on Precinct 13 2003 special edition DVD.

- ^ Production Gallery (included in the 2003 special edition Region 1 DVD of Assault on Precinct 13). 2003.

- ^ a b "Syfy – Watch Full Episodes | Imagine Greater". Scifi.com. Archived from the original on February 10, 2006. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ a b "John Carpenter: Press: Rolling Stone: 6–28–79". Rolling Stone. June 28, 1979. Archived from the original on February 28, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2015 – via Theofficialjohncarpenter.com.

- ^ a b "Bob Clark Interview". May 2005. Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- ^ Audio commentary by John Carpenter and Debra Hill in The Fog, 2002 special edition DVD

- ^ Ragusa, Gina (October 19, 2018). "What Was the Budget for The Original 'Halloween' And What Did The Cast Get Paid?". Showbiz Cheat Sheet. Retrieved September 24, 2025.

- ^ "Halloween". Houseofhorrors.com. Archived from the original on April 6, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ "John Carpenter: Press: Chic Magazine: August 1979". Theofficialjohncarpenter.com. Archived from the original on November 4, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ "Killing His Contemporaries: Dissecting The Musical Worlds Of John Carpenter". Archived from the original on June 13, 2006.

- ^ Interview with John Carpenter in the 2005 documentary film, Tales from the Crypt from Comic Books to Television.

- ^ a b Audio commentary by John Carpenter and Debra Hill in The Fog, 2002 special edition DVD.

- ^ "'The Fog': A Spook Ride On Film". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 28, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2019 – via theofficialjohncarpenter.com.

- ^ "Escape from New York". Rotten Tomatoes. July 10, 1981. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ [1] Archived July 30, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bauer 1999.

- ^ Kirk 2011.

- ^ Bacle 2014.

- ^ Nashawaty 2020.

- ^ Leitch & Grierson 2017.

- ^ Paul 2017.

- ^ Lambie 2018a.

- ^ Lambie 2017b.

- ^ Abrams 2016.

- ^ Nicholls 2016.

- ^ Corrigan 2017.

- ^ Anderson, K 2015.

- ^ O'Neill 2013.

- ^ a b Muir 2013, p. 285.

- ^ Zoller Seitz 2016.

- ^ Thurman 2017.

- ^ Empire500 2008.

- ^ Mahon 2018.

- ^ LegBoston 2007.

- ^ Interview with John Carpenter on the DVD documentary film "Christine: Ignition"

- ^ [2] Archived February 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "John Carpenter: Press: Los Angeles Herald Examiner: 12–14–84". Theofficialjohncarpenter.com. December 14, 1984. Archived from the original on November 4, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ "John Carpenter: Press: LA Weekly: 12-14/20-84". Theofficialjohncarpenter.com. Archived from the original on November 4, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ "In the Mouth of Madness". Rotten Tomatoes. February 3, 1995. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ Calia, Michael (December 5, 2014). "In the Mouth of John Carpenter's Misunderstood Masterpiece". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 20, 2016.

- ^ "John Carpenter Talks Cult Classic 'Escape from L.A.' and Being Open to Directing Again". Forbes.

- ^ "Escape from L.A. Director John Carpenter Looks Back at the Cult-Hit Action Film". February 18, 2022.

- ^ "Sentinel Returns Soundtrack – Review". Bestwesterngamessoundtracks.com. May 14, 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- ^ "Badass Announcement Trailer – F.E.A.R. 3". DreadCentral. August 29, 2012.

- ^ "John Carpenter to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award from the Freak Show Horror Film". DreadCentral. October 11, 2012.

- ^ "John Carpenter's Lost Themes". DreadCentral. January 13, 2015.

- ^ "John Carpenter To Perform His Film Soundtracks And New Compositions In London & Manchester Over Halloween 2016". All Tomorrow's Parties.

- ^ Minsker, Evan (February 1, 2016). "John Carpenter Announces New LP Lost Themes II". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ^ Grow, Kory (August 22, 2017). "Filmmaker John Carpenter to Revisit Greatest Hits on New Album". Rolling Stone. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

- ^ "Big Breaking Halloween Movie News from John Carpenter and Blumhouse". Dread Central. May 23, 2016. Retrieved May 24, 2016.

- ^ "The Official John Carpenter – The official website of John Carpenter". Theofficialjohncarpenter.com. October 15, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2022.

- ^ Marshall, Cass (June 8, 2023). "John Carpenter has a new Left 4 Dead-like game with zombies that 'blow up real good'". Polygon. Vox Media. Archived from the original on June 8, 2023. Retrieved June 19, 2023.

- ^ Romano, Sal (August 19, 2025). "John Carpenter's Toxic Commando launches in early 2026". Gematsu. Retrieved August 19, 2025.

- ^ Nelson, Samantha (August 25, 2025). "John Carpenter's newest horror is actually a game — and I played it". Polygon. Valnet. Retrieved August 26, 2025.

- ^ Tallerico, Brian (October 10, 2023). "John Carpenter Returns with Peacock Project That Doesn't Deserve His Name". Roger Ebert.com. Retrieved December 28, 2024.

- ^ Bergeson, Samantha (June 2, 2023). "John Carpenter Returns to Directing with TV Series He Made from His Couch". IndieWire. Retrieved December 28, 2024.

- ^ Richlin, Harrison (December 8, 2024). "'Anora' Wins Best Picture from Los Angeles Film Critics Association — Winners List". IndieWire. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ Vlessing, Etan (October 17, 2025). "John Carpenter to Exec Produce Supernatural Horror Anthology Series (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 19, 2025.

- ^ John Carpenter Season, starandshadow.org.uk: Village Voice, 2010, retrieved January 23, 2021

- ^ SLIS (January 28, 2015). "7 Best John Carpenter Soundtracks". Smells Like Infinite Sadness. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ "Interview with John Carpenter". outpost31.com. August 2012. Archived from the original on August 11, 2012.

- ^ a b "John Carpenter Interview & Gear Guide". PMT Online. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- ^ "Death Waltz announce reissue of John Carpenter and Alan Howarth's They Live OST – FACT Magazine: Music News, New Music". Factmag.com. February 8, 2013. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- ^ "We Asked John Carpenter (Almost) Every Question You Could Think of About His Career – Noisey". Noisey.vice.com. July 26, 2014. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- ^ Konow, David (April 9, 2015). "John Carpenter fans really need to listen to this killer mixtape based on his films". Consequence of Sound. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- ^ Jeremy Gordon (September 30, 2015). "John Carpenter Announces First Live Performance". Pitchfork. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- ^ Dave McNary (May 24, 2016). "'Halloween' Sequel Set Up With John Carpenter". Variety. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- ^ "The Rise of the Synths | A documentary of Synthwave". The Rise of the Synths (in Spanish). Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ "Doc'n Roll Film Festival – The Rise of The Synths". Docnrollfestival.com. Archived from the original on September 30, 2019. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ "GUNSHIP | Retro Futuristic Assault". Archived from the original on October 2, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- ^ "Daniel Davies Signals". Allmusic.com. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ^ "John Carpenter Shares Chilling New Song "The Dead Walk": Stream". Consequence of Sound. December 7, 2020. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ^ Ewing, Jerry (July 4, 2020). "John Carpenter Streams Two New Songs". Prog. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ^ Christie, Erin (October 27, 2020). "John Carpenter announces 'Lost Themes III" (listen to "Weeping Ghost")". Brooklyn Vegan. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ^ "Anthology II: Movie Themes 1976–1988".

- ^ "John Carpenter announces new album 'Lost Themes IV: Noir', shares "My Name is Death" video".

- ^ "John Carpenter".

- ^ Rettig, James (March 6, 2024). "John Carpenter, Cody Carpenter, & Daniel Davies – "My Name Is Death"". Stereogum. Retrieved February 8, 2025.

- ^ Roger Ebert (February 3, 1980). "Interview with Adrienne Barbeau". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on June 29, 2006. Retrieved March 9, 2006.

- ^ [3] Archived May 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [4] Archived December 24, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Earl, William (January 10, 2023). "Sandy King Carpenter Was Sick of Comic Book Industry Gatekeepers. A Decade Later, Her Self-Started Publishing House Is Scary Successful". Variety. Retrieved February 9, 2025.

- ^ "John Carpenter Hasn't Talked to Dwayne Johnson About 'Big Trouble in Little China' – Speakeasy – WSJ". Blogs.wsj.com. June 11, 2015. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- ^ "Animal Icons". TV Guide. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ Bowe, Miles (November 9, 2017). "Level Up: Horror master John Carpenter on his 20-year Sonic The Hedgehog addiction". Fact. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ^ "John Carpenter and Steve Niles Contributing To 'F.E.A.R. 3'". Multiplayerblog.mtv.com. April 8, 2010. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ a b Hughes, William (October 11, 2022). "John Carpenter talks us through his favorite video games of 2022, plus scoring Halloween Ends". The A.V. Club. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ^ Carpenter, John [@TheHorrorMaster] (November 21, 2023). "I've played FALLOUT 76 on and off for the last 5 years, and I'm here to say it's a great game!" (Tweet). Retrieved January 5, 2024 – via Twitter.

- ^ Armitage, Hugh (May 9, 2013). "John Carpenter wants 'Dead Space' film". Digitalspy.co.uk. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- ^ POST MORTEM: John Carpenter — Part 4, August 14, 2014, retrieved June 15, 2023

- ^ "John Carpenter Is Scared". Esquire. October 29, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2023.

- ^ "About This Program – National Film Preservation Board | Programs | Library of Congress". Loc.gov. Archived from the original on July 9, 2014. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ "A History of Horror with Mark Gatiss – Q&A with Mark Gatiss". BBC. Retrieved November 12, 2010.

- ^ Stice, Joel (October 25, 2014). "How James Cameron's Bad Dream Launched One Of Sci-fi's Biggest Franchises". Uproxx. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ^ a b Freer, Ian (January 7, 2016). "Paranoia, claustrophobia, lots of men: how The Thing inspired Tarantino's Hateful Eight". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ^ Fitzmaurice, Larry (August 28, 2015). "Quentin Tarantino: The Complete Syllabus of His Influences and References". Vulture. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ^ Nordine, Michael (May 23, 2016). "Guillermo del Toro Praises John Carpenter in Epic Twitter Marathon". IndieWire. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ^ Rodriguez, Robert (October 8, 2013). "'Machete Kills' Director Robert Rodriguez on His Favorite Cult Movies". The Daily Beast. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ^ Joiner, Whitney (January 28, 2007). "Directors Who Go Together, Like Blood and Guts". The New York Times. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- ^ Bowles, Duncan (June 13, 2016). "James Wan interview: The Conjuring 2, Fast 7, Statham". Den of Geek!. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- ^ Taylor, Drew (August 21, 2013). "Interview: Edgar Wright Talks 'The World's End,' Completing The Cornetto Trilogy, 'Ant-Man' & Much More". IndieWire. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ Hiatt, Brian (October 30, 2004). "Shaun of the Dead director: My top horror films". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- ^ Zinoman, Jason (August 19, 2011). "What Spooks the Masters of Horror?". The New York Times. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- ^ Monahan, Mark (May 21, 2005). "Film-makers on film: Danny Boyle". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ Brown, Todd (September 12, 2009). "TIFF 09: Nicolas Winding Refn Talks VALHALLA RISING". Screen Anarchy. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ^ Perez, Rodrigo (July 16, 2010). "Nicolas Winding Refn Talks The Druggy & Spiritual Science-Fiction Of 'Valhalla Rising'". theplaylist.net. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ^ Ebiri, Bilge (July 15, 2010). "Nicolas Winding Refn's Rising Star". IFC. IFC. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ^ Fitzmaurice, Larry (July 25, 2013). "Nicolas Winding Refn and Cliff Martinez". Pitchfork. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Collis, Clark (July 16, 2014). "2014's most influential director: John Carpenter?". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ^ a b Patches, Matt (September 10, 2014). "How Adam Wingard and Simon Barrett Distilled 'Re-Animator,' 'The Stepfather,' John Woo, and More Into 'The Guest'". Grantland. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ^ a b Taylor, Drew (October 9, 2014). "'The Guest' Writer & Director Discuss '80 Influences, Their Aborted 'You're Next' Sequel & More". IndieWire. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ^ Hewitt, Chris (October 30, 2015). "Neil Marshall And Axelle Carolyn: The First Couple Of Horror". Empire. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ^ Marshall, Neil (Director) (2008). Doomsday (Unrated DVD). Universal Pictures.

Feature commentary with director Neil Marshall and cast members Sean Pertwee, Darren Morfitt, Rick Warden and Les Simpson.

- ^ Phillips, Jevon (October 28, 2013). "'Trick 'R Treat' director Michael Dougherty on cult horror, Halloween". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- ^ Borders, Meredith (October 29, 2013). "Badass Interview: Mike Dougherty On What He'd Like To Include In The TRICK 'R TREAT Sequel". Birth.Movies.Death. birthmoviesdeath.com. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- ^ "Ben Wheatley's Top 10 Horrific Films". Film4. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ a b Walker, R.V. (November 21, 2015). "Michael Shannon is On the Run in Supernatural MIDNIGHT SPECIAL Trailer" Archived March 14, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Nerdist.

- ^ a b Foutch, Haleigh (November 13, 2015). "'Midnight Special': First Image and Poster Reveal Michael Shannon's Superpowered Son". Collider.

- ^ Joon-ho, Bong (October 30, 2013). "Joon-Ho Bong On Friends And Frenemies in Monster Films". Oyster. Archived from the original on March 25, 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- ^ Trunick, Austin (June 27, 2014). "Director Bong Joon-ho on his latest film, Snowpiercer". Under the Radar. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- ^ Bellette, Kwenton (October 15, 2013). "Busan 2013: Highlights From The Tarantino And Bong Joon-ho Open Talk". Screen Anarchy. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- ^ Weintraub, Steve (March 7, 2007). "Exclusive Interview with Bong Joon-ho". Collider. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- ^ Schager, Nick (March 30, 2016). "'Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2' Director James Gunn in Fan Chat: Groot's Based on My Dog". Yahoo!. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- ^ Grove, David (July 1, 2016). "Exclusive: Mike Flanagan Not Directing Next Halloween Film: 'I'm Not Doing It'". ihorror.com. Archived from the original on March 25, 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- ^ Gingold, Michael (March 12, 2015). "Q&A: Writer/Director David Robert Mitchell on His Terrifying Youth-Horror Film "IT FOLLOWS"". Fangoria. Archived from the original on May 1, 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ^ Taylor, Drew (March 12, 2015). "Director David Robert Mitchell Reveals The 5 Biggest Influences On 'It Follows'". IndieWire. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ^ Goldman, Eric (July 7, 2016). "How Steven Spielberg, John Carpenter and Stephen King Influenced Stranger Things". IGN. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ^ Zuckerman, Esther (July 13, 2016). "The Stranger Things creators want some scares with their Spielberg". The A.V. Club. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- ^ Jagernauth, Kevin (May 2, 2016). "'Green Room' Director Jeremy Saulnier's Top 5 John Carpenter Movies". theplaylist.net. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- ^ Lamble, Ryan (May 13, 2016). "Jeremy Saulnier interview: Green Room, John Carpenter". denofgeek.com. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- ^ Allen, Nick (June 5, 2017). "A Zombie with No Conscience: Trey Edward Shults on "It Comes at Night"". rogerebert.com. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- ^ Robinson, Tasha (June 8, 2017). "Why the director of It Comes At Night hopes audiences "don't catch on" to his technological tricks". The Verge. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- ^ Hoffman, Jordan (April 11, 2012). "Drew Goddard Interview: The Director Takes Us Inside the 'Cabin in the Woods'". ScreenCrush. Retrieved November 19, 2016.

- ^ Kirk, Jeremy (April 13, 2012). "Interview: 'Cabin in the Woods' Co-Writer & Director Drew Goddard". firstshowing.net. Retrieved November 19, 2016.

- ^ Brooks, Tamara (August 10, 2017). "Shazam Director Revives Old-School Horror with Annabelle: Creation". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- ^ Weinberg, Scott (August 13, 2007). "Interview: 'Hatchet' Grinder Adam Green!". Moviefone. Archived from the original on March 24, 2017. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- ^ Geoghegan, Ted (September 29, 2015). "13 Films That Influenced Ted Geoghegan's 'We Are Still Here'". frightday.com. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ^ Asch, Mark (June 4, 2015). ""I pine for the cinema of my youth": Talking to We Are Still Here Director Ted Geoghegan". L Magazine. Archived from the original on November 16, 2016. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ^ Tonguette, Peter (October 1, 2004). "Keith Gordon on Keith Gordon, Part One: From Actor to Director". sensesofcinema.com. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ^ Smith, Mike (February 3, 2011). "Interview with Keith Gordon". mediamikes.com. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ^ Stone, Ken (July 25, 2020). "San Diego's Spielberg? Q&A With Director Brian Butler Near Sci-Fi Film Premiere". Times of San Diego. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ Halen, Adrian (November 17, 2021). "'Friend of the World' streaming and on demand Nov 22nd". Horror News | HNN. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ Wien, Gary (October 19, 2014). "Infliction: An Interview With Jack Thomas Smith". New Jersey Stage.

- ^ a b Zimmerman, Samuel (May 1, 2014). "'Blood Glacier' (Movie Review)" Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Fangoria.

- ^ Gonzalez, Ed (April 27, 2014). "Review: Blood Glacier". Slant Magazine.

- ^ Abrams, Simon. "BLOOD GLACIER (review)". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- ^ Hunter, Rob (April 30, 2014). "'Blood Glacier' Review: A Nature Trail to Hell". Film School Rejects. FSR. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- ^ Holland, Luke (May 15, 2013). "Top 10 games that should be movies – and their ideal directors". The Guardian.

- ^ David Grove (February 2005). Making Friday the 13th: The Legend of Camp Blood. FAB Press. pp. 11–12. ISBN 1-903254-31-0.

- ^ Mentioned on Durch die Nacht mit …. Episode dated October 3, 2003.

- ^ Wilner, Norman (March 29, 2017). "The Void is chock full of imaginative thrills". NOW Magazine. Retrieved June 15, 2019.[dead link]

- ^ Reed, Ryan (July 3, 2020). "Hear John Carpenter's New Songs 'Skeleton,' 'Unclean Spirit'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

Works cited

[edit]- Abrams, Simon (October 13, 2016). "The Men Who Were The Thing Look Back on a Modern Horror Classic". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on February 3, 2018. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- Anderson, K (January 19, 2015). "Directors Cuts: Top 5 John Carpenter Movies". Nerdist. Archived from the original on February 12, 2018. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

- Bacle, Ariana (April 22, 2014). "'E.T.': Best Summer Blockbusters, No. 6". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on February 11, 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- Bauer, Erik (January 1999). "John Carpenter on The Thing". creativescreenwriting. Archived from the original on January 27, 2018. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- Corrigan, Kalyn (October 31, 2017). "Every John Carpenter Movie, Ranked from Worst to Best". Collider. Archived from the original on February 7, 2018. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- "Empire's The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire. 2008. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- Greene, Andy (October 8, 2014). "Readers' Poll: The 10 Best Horror Movies of All Time". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 8, 2018. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- Kirk, Jeremy (July 13, 2011). "The 36 Things We Learned From John Carpenter's 'The Thing' Commentary Track". Film School Rejects. Archived from the original on January 30, 2018. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- Lambie, Ryan (June 26, 2017b). "Examining the critical reaction to The Thing". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on June 26, 2017. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- Lambie, Ryan (January 4, 2018a). "John Carpenter's The Thing Had An Icy Critical Reception". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on June 26, 2016. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- "1. 'The Thing' (1982) (Boston.com's Top 50 Scary Movies of All Time)". The Boston Globe. October 25, 2007. Archived from the original on October 25, 2007. Retrieved June 5, 2016 – via Internet Archive.

- Leitch, Will; Grierson, Tim (September 6, 2017). "Every Stephen King Movie, Ranked From Worst to Best". Vulture.com. Archived from the original on September 6, 2017. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- Mahon, Christopher (January 16, 2018). "How John Carpenter'S The Thing Went From D-List Trash To Horror Classic". SYFY WIRE. Syfy. Archived from the original on January 17, 2018. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- Muir, John Kenneth (2013). Horror Films of the 1980s. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-5501-0.

- Nashawaty, Chris (June 25, 2020). "38 Years Ago Today Two of the Best Sci-Fi Films of All Time Bombed in Theaters. What Happened?". Esquire. Archived from the original on October 21, 2022. Retrieved December 29, 2022.

- Nicholls, Peter (June 28, 2016). "Thing, The". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Archived from the original on June 28, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- O'Neill, Phelim (October 31, 2013). "John Carpenter: 'Halloween's a very simple film'". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on February 13, 2018. Retrieved February 13, 2018.

- Paul, Zachary (June 25, 2017). "From "Instant Junk" to "Instant Classic" – Critical Reception of 'The Thing'". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on February 7, 2018. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- Thurman, Trace (June 25, 2017). "John Carpenter's 'The Thing' Turns 35 Today!". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on February 4, 2018. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- Zoller Seitz, Matt (October 9, 2016). "30 Minutes On: "The Thing" (1982)". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

Bibliography

[edit]- Conrich, Ian, Woods, David eds (2004). The Cinema of John Carpenter: The Technique of Terror (Directors' Cuts). Wallflower Press. ISBN 1904764142.

- Hanson, Peter, Herman, Paul, Robert eds. (2010). Tales from the Script (Paperback ed.). New York, NY: HarperCollins Inc. ISBN 9780061855924.

- Muir, John, Kenneth. The Films of John Carpenter, McFarland & Company, Inc. (2005). ISBN 0786422696.