Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Warren Commission.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Warren Commission

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Warren Commission

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

The President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, known as the Warren Commission, was a special investigative body established by President Lyndon B. Johnson through Executive Order 11130 on November 29, 1963, to examine the circumstances surrounding the assassination of President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963, in Dallas, Texas, including the subsequent killing of accused assassin Lee Harvey Oswald.[1][2]

Chaired by U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren, the commission comprised seven members: Democratic Senator Richard Russell Jr. of Georgia, Republican Senator John Sherman Cooper of Kentucky, Democratic House Majority Whip Hale Boggs of Louisiana, Republican Representative Gerald R. Ford of Michigan, former CIA Director Allen Dulles, and former World Bank President John J. McCloy.[1]

Over ten months, the commission reviewed thousands of documents, interviewed hundreds of witnesses, and relied heavily on FBI investigations before issuing its September 1964 report, which determined that Lee Harvey Oswald fired three shots from the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository, killing Kennedy and wounding Governor John Connally, with no evidence of conspiracy or foreign involvement, and that Jack Ruby acted independently in murdering Oswald two days later.[3][4]

Despite these findings, the report has been persistently contested for inconsistencies such as the improbable single-bullet trajectory required to match wounds and timelines, Oswald's disputed marksmanship proficiency, overlooked witness accounts of shots from other locations, and potential withholding of intelligence agency information, fostering enduring public doubt and prompting later probes like the 1979 House Select Committee on Assassinations, which affirmed Oswald as the shooter but indicated a probable conspiracy based on acoustic analysis later challenged on technical grounds.[5][6][7]

J. Lee Rankin served as general counsel, overseeing a staff of approximately 14 assistant counsels and 12 additional personnel drawn from prominent legal backgrounds.[16] Rankin, former U.S. Solicitor General, was appointed to direct the Commission's legal and investigative efforts.[17] The selection of members reflected a bipartisan composition, though initial reluctance was reported from Warren and Russell before their acceptance.[6]

This integrated approach yielded a coherent sequence supporting shots fired sequentially from a single elevated rear position, with the motorcade's arrival at Parkland Memorial Hospital by 12:35 p.m. marking the immediate aftermath.[30]

Establishment

Historical Context of the Assassination

On November 22, 1963, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated while riding in an open-top limousine through Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas, during a scheduled political visit to the state.[8] The event took place at approximately 12:30 p.m. local time, as the presidential motorcade proceeded from Dallas Love Field airport toward the downtown area, following a brief stopover from Fort Worth.[9] Kennedy had arrived in Texas the previous day as part of a multi-city tour aimed at mending intra-party divisions within the Democratic ranks, particularly between liberal and conservative factions in a state critical to his reelection prospects for 1964.[8] The trip reflected broader political dynamics of Kennedy's presidency, marked by efforts to consolidate support in the South amid ongoing civil rights advancements and economic recovery initiatives. Texas Governor John Connally, a Kennedy appointee, accompanied the president, underscoring the itinerary's focus on unifying Democratic leadership.[9] Advance preparations had been underway for weeks, involving coordination with local authorities for security along the 10-mile motorcade route, which included a slow passage through crowded streets to maximize public exposure.[9] Dallas, in particular, hosted a segment planned to culminate at a luncheon with business and political leaders, though the city had seen vocal anti-Kennedy demonstrations in prior months due to perceptions of his administration's liberal policies.[8] This assassination unfolded against the backdrop of intensified U.S.-Soviet rivalry during the Cold War, including the lingering effects of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, where Kennedy's naval quarantine of Cuba averted nuclear escalation but heightened domestic scrutiny of perceived communist threats.[10] Lee Harvey Oswald, a former U.S. Marine who had defected to the Soviet Union in 1959 before returning in 1962, was arrested within hours of the shooting; he had been employed at the Texas School Book Depository building overlooking Dealey Plaza and maintained pro-Castro sympathies through affiliations like the Fair Play for Cuba Committee.[8] The rapid sequence of events—Kennedy's death pronounced at Parkland Hospital shortly after the shots, followed by Oswald's murder two days later by nightclub owner Jack Ruby—fueled immediate public demands for a thorough federal inquiry into potential conspiracies amid the era's geopolitical suspicions.[11]Creation and Legal Mandate

On November 29, 1963, seven days after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963, in Dallas, Texas, President Lyndon B. Johnson issued Executive Order 11130, formally establishing the President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, known as the Warren Commission.[2][12] The order responded to immediate public speculation and international concerns about potential conspiracies involving foreign powers, aiming to ascertain facts and mitigate risks of escalation.[13] The Commission's primary legal mandate, as outlined in the executive order, was to "ascertain, evaluate, and report upon the facts relating to the assassination of the late President John F. Kennedy and related events," including the circumstances of Lee Harvey Oswald's killing by Jack Ruby two days later.[2][14] This involved examining evidence gathered by federal agencies such as the FBI, conducting an independent review of all pertinent circumstances, and providing a comprehensive report to the President with any recommendations for preventing similar incidents.[1][6] Unlike a judicial body, the Commission lacked prosecutorial authority and served solely as an investigative panel to compile and analyze information without binding legal determinations. Executive Order 11130 granted the Commission specific powers, including the authority to subpoena witnesses or documents, administer oaths, and hold public or private hearings as deemed necessary.[15] Johnson appointed Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren as chairman, along with six other members: Senators Richard Russell Jr. and John Sherman Cooper, Representatives Hale Boggs and Gerald Ford, former CIA Director Allen Dulles, and banker John J. McCloy.[2] The order stipulated that the Commission report its findings as promptly as possible, emphasizing thoroughness amid pressures to resolve uncertainties surrounding the national trauma.[13]Organization and Operations

Membership and Key Personnel

The Warren Commission, formally the President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, was established by Executive Order 11130 signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson on November 29, 1963.[2] The order appointed seven members, selected for their prominence in government, law, and intelligence, to investigate the assassination of President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963, and the subsequent killing of Lee Harvey Oswald.[1]| Member | Position | Background |

|---|---|---|

| Earl Warren | Chairman | Chief Justice of the United States; former Governor and Attorney General of California.[1] |

| Richard B. Russell, Jr. | Member | U.S. Senator from Georgia (Democrat).[1] |

| John Sherman Cooper | Member | U.S. Senator from Kentucky (Republican).[1] |

| Hale Boggs | Member | U.S. Representative from Louisiana (Democrat).[1] |

| Gerald R. Ford | Member | U.S. Representative from Michigan (Republican); House Minority Leader.[1] |

| Allen W. Dulles | Member | Former Director of Central Intelligence (1953–1961).[1] |

| John J. McCloy | Member | Former President of the World Bank; former U.S. High Commissioner for Germany.[1] |

Meetings, Procedures, and Resource Allocation

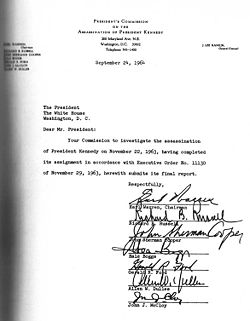

The Warren Commission convened its initial formal meeting on December 5, 1963, at the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C., where members organized their approach and assigned preliminary tasks. Subsequent executive sessions followed on December 6 and 16, 1963, focusing on early investigative priorities such as Oswald's potential connections to foreign entities, and additional sessions occurred, including one on January 27, 1964, to address specific allegations like Oswald's alleged FBI informant status. In total, the Commission held 12 formal meetings over its tenure, culminating in the September 24, 1964, session at which the final report was approved and delivered to President Lyndon B. Johnson.[18][19] Commission procedures centered on compiling evidence through agency-supplied materials rather than independent fieldwork, with staff divided into teams to examine discrete topics such as Oswald's biography, the shooting sequence, and possible conspiracies. Primary reliance was placed on the FBI's extensive investigation, which furnished thousands of documents, interviews, and forensic analyses, supplemented by inputs from the CIA, Secret Service, and other agencies; this dependence stemmed from the Commission's limited mandate and timeline under Executive Order 11130. Staff attorneys took sworn depositions from 395 witnesses, while 94 witnesses testified directly before one or more Commissioners in hearings requiring at least one member present; depositions involved oaths, rights to counsel, three-day notice (often waived), and stenographic transcripts, but lacked courtroom-style confrontation or compulsory process for most evidence, prioritizing cooperative requests over subpoenas. The Commission assessed credibility through cross-referencing reports and internal debates, diverging from trial standards by emphasizing comprehensive documentation over adversarial testing.[13][20][21] Resource allocation supported a compact operation, with a core staff of about 83 members—including 15-20 lead attorneys under General Counsel J. Lee Rankin, plus researchers, historians, and clerks—coordinated from temporary offices in the National Archives and later the VFW Building. This was augmented by roughly 222 detailed personnel from federal agencies, enabling focused efforts without a large permanent investigative force; for instance, FBI agents handled most witness interviews and physical evidence collection. The total expenditure reached $1.2 million across the approximately 10-month period, covering salaries, travel, transcription, and printing, with no formal congressional appropriation but funding drawn from executive contingency resources. Such constraints, while promoting efficiency, constrained original inquiries, as the Commission deferred to agency expertise on technical matters like ballistics and cryptography.[22][21]Core Investigations

Examination of Lee Harvey Oswald

The Warren Commission conducted an extensive investigation into Lee Harvey Oswald, compiling evidence from interviews, documents, forensic analysis, and witness statements to determine his role in the assassination of President Kennedy. This examination spanned Oswald's early life, military service, international travels, domestic activities, and immediate post-assassination behavior, ultimately concluding that he fired the fatal shots from the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository.[23][24] Key sources included testimony from Oswald's wife, Marina, FBI records, and ballistic comparisons, with no credible evidence emerging of foreign or domestic conspirators directing his actions.[23][24] Oswald was born on October 18, 1939, in New Orleans, Louisiana, to a widowed mother, Marguerite, following his father's death two months prior; the family faced financial instability, leading to frequent relocations and Oswald's placement in an orphanage from ages 3 to 6.[24] He exhibited early behavioral issues, including truancy and a 1953 psychiatric evaluation noting immaturity and hostility, though no severe pathology.[24] Enlisting in the U.S. Marine Corps in October 1956 at age 17, Oswald qualified as a sharpshooter with rifle scores of 212 in December 1956 and 191 in May 1959, receiving training in marksmanship and receiving an undesirable discharge in 1962 after his Soviet defection.[23][24] In October 1959, at age 19, he defected to the Soviet Union, renouncing U.S. citizenship and attempting suicide upon initial rejection; he resided in Minsk until June 1962, marrying Marina Prusakova in April 1961 and fathering a daughter, June, before returning to the U.S. disillusioned with Soviet life.[24] Upon repatriation via Fort Worth, Texas, Oswald secured intermittent employment while expressing Marxist sympathies, subscribing to publications like The Worker and The Militant, and founding a one-man chapter of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee in New Orleans by August 1963.[24] There, he distributed pro-Castro leaflets under the alias "A. Hidell," clashed with anti-Castro exiles, and was arrested on August 9, 1963, for disturbing the peace after a street altercation.[24] Relocating to Dallas in late September 1963, he obtained a job at the Texas School Book Depository on October 16, 1963, from which vantage point the shots were fired; he practiced with firearms, including hunting trips, and on April 10, 1963, attempted to assassinate retired Major General Edwin A. Walker, firing a shot that missed Walker's head, as corroborated by Marina Oswald's testimony, a farewell note, and ballistic evidence linking the bullet to Oswald's rifle with fair probability.[23][24] The Commission established Oswald's ownership of the 6.5-millimeter Mannlicher-Carcano rifle (serial C2766) used in the assassination through a March 13, 1963, mail-order purchase from Klein's Sporting Goods in Chicago, shipped to "A. J. Hidell" at Oswald's Dallas post office box on March 20, 1963, confirmed by handwriting analysis on the order form and envelope.[23] His palmprint appeared on the rifle barrel, fibers from his shirt matched those on the weapon, and backyard photographs dated March 31, 1963, depicted him holding the rifle and a pistol, authenticated by photographic experts.[23] On November 22, 1963, Oswald carried the disassembled rifle to the Depository in a paper bag, as evidenced by his prints on the bag and cartons positioned at the sixth-floor sniper's nest; three spent cartridge cases recovered there matched the rifle via FBI ballistic tests.[23] Eyewitness Howard Brennan identified Oswald in the window moments after the shots, describing a man aiming a rifle.[23] Following the assassination at approximately 12:30 p.m., Oswald departed the Depository around 12:33 p.m., traveling by bus and taxi to his rooming house at 1026 North Beckley Avenue, arriving near 1:00 p.m., then proceeding on foot.[23] At about 1:15-1:16 p.m., he fatally shot Dallas Police Officer J. D. Tippit on Tenth Street and Patton Avenue after Tippit stopped him; twelve eyewitnesses identified Oswald as the shooter, who emptied his Smith & Wesson revolver (serial V510210), with four bullets matching the weapon recovered from him upon arrest at the Texas Theatre around 1:50 p.m., where he resisted officers while armed.[23] The Commission found these actions indicative of flight and guilt, with Oswald possessing $13.87 and leaving $170 at home, inconsistent with routine behavior.[23][24] Oswald's political ideology—rooted in Marxism, admiration for Fidel Castro, and resentment toward U.S. policies, particularly on Cuba—combined with personal alienation, marital strife, and a quest for notoriety, formed the basis for inferred motives, as detailed in his writings and Marina's accounts of his post-Mexico City trip despondency in September-October 1963.[24] Despite contacts with Soviet and Cuban embassies in Mexico City and Fair Play for Cuba affiliations, the Commission uncovered no evidence of encouragement or employment by foreign powers, nor domestic conspiracy, attributing the assassination to Oswald's solitary initiative.[23][24] Interrogations of Oswald from 2:30 p.m. on November 22 until his death yielded no confession, but circumstantial and forensic linkages prevailed in the Commission's assessment.[25]Ballistics, Forensics, and Physical Evidence

The Warren Commission examined a 6.5-millimeter Italian Mannlicher-Carcano rifle, serial number C2766, recovered from the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository on November 22, 1963, along with three cartridge cases and matching live ammunition traced to Oswald's mail-order purchase under the alias "A. Hidell."[4] Firearms identification experts from the FBI and U.S. Army Ballistics Research Laboratory conducted tests, firing the rifle and comparing rifling marks, which conclusively matched the cartridge cases and two large bullet fragments recovered from the presidential limousine and Connally's stretcher to this weapon.[4][26] A nearly intact bullet, designated Commission Exhibit 399 (CE 399), found on a stretcher at Parkland Hospital, exhibited rifling characteristics consistent with the rifle, though its minimal deformation after purportedly traversing two bodies was noted in expert testimony as unusual but possible for full-metal-jacket ammunition.[4] Forensic analysis included neutron activation and emission spectrography of bullet fragments: two large pieces from the front seat of the limousine (one weighing 21.0 grains, the other 20.0 grains) and smaller fragments from Connally's wrist and thigh wounds showed lead composition and trace elements aligning with Western Cartridge Company ammunition used in the rifle tests.[26] These matches supported the Commission's determination that all recovered projectiles originated from Oswald's rifle, excluding other weapons.[4] However, the spectrographic method's limitations in distinguishing individual bullets from the same manufacturing batch were later highlighted in independent reviews, as it relied on bulk elemental similarities rather than unique isotopic signatures.[27] The autopsy, performed at Bethesda Naval Hospital on November 22, 1963, documented two bullet wounds to Kennedy: an entry in the upper back at the third thoracic vertebra (approximately 5.5 inches below the mastoid process), exiting the throat, and a fatal tangential entry in the rear skull above the external occipital protuberance, causing massive brain disruption with 1500 grams of fragmented tissue and exit fragmentation forward.[28][29] X-rays revealed metallic fragments along the head wound track, with the largest (7 by 2 millimeters) near the right orbit, consistent with a high-velocity 6.5-millimeter projectile's disintegration.[28] Pathologists noted no evidence of frontal entry wounds, attributing all damage to rear-origin shots, though chain-of-custody issues from Parkland to Bethesda, including unexamined initial hospital records, complicated wound trajectory reconstructions.[4] Connally's autopsy confirmed entry in the back below the right shoulder blade, shattering his fifth rib, exiting below the right nipple, then fragmenting his wrist and embedding in the thigh, with removed fragments matching the limousine debris.[4] Physical evidence from the limousine included a cracked windshield puncture attributed to a bullet fragment, bullet holes in the interior trim, and trace blood spatter patterns aligning with shots from above and behind.[4] The Commission relied on these elements, supplemented by wound ballistics simulations using gelatin blocks and animal proxies, to validate the rifle's capability for the observed damage at ranges of 175 to 265 feet.[4] Despite the linkages, critics of the Commission's forensic methodology, including subsequent analyses, have pointed to inconsistencies such as the back wound's shallow depth (not traversing fully as initially probed at Parkland) and potential contamination of fragments, underscoring reliance on 1960s-era techniques predating advanced forensic standards.[27]Witness Accounts and Timeline Reconstruction

The Warren Commission gathered affidavits and testimonies from approximately 552 witnesses, including over 100 in Dealey Plaza, to reconstruct the timeline and sequence of the assassination on November 22, 1963. These accounts, supplemented by motion picture films such as Abraham Zapruder's 8-millimeter home movie and police radio logs, established that the presidential motorcade entered Dealey Plaza around 12:30 p.m. Central Standard Time, with shots fired as the limousine traversed Elm Street toward the Triple Underpass. Witnesses like Secret Service agent Rufus W. Youngblood and aide David F. Powers corroborated the 12:30 p.m. timing based on clocks at the Texas School Book Depository and expectations for arrival at the Trade Mart luncheon.[30][30] Eyewitness descriptions of the shots varied in number—most reported two to three fired in rapid succession over 4.8 to 5.6 seconds—but converged on a rifle-like report echoing in the plaza. Governor John Connally, seated ahead of President Kennedy, testified to hearing an initial shot, then feeling struck by a subsequent one in the back, followed by observing the fatal head wound; his wife, Nellie Connally, and driver William Greer described a similar sequence of reactions starting with a "backfire" noise, then slumping and the head shot.[30][30] A majority of witnesses who identified a direction, including those near the grassy knoll and underpass, attributed the sounds to the rear, specifically the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository; steamfitter Howard Brennan provided a detailed account of seeing a man aiming and firing a rifle from the Depository's southeast corner window, later identifying Lee Harvey Oswald in a lineup as resembling the shooter.[4][4] The Commission's timeline reconstruction synchronized these testimonies with the Zapruder film, which filmed at 18.3 frames per second and depicted the limousine traveling at 11.2 miles per hour, covering 186 feet in the critical 8.3 seconds (frames 150 to 302). The film showed Kennedy emerging from behind a sign at frame 225 with hands at throat (consistent with a neck wound reaction), Connally twisting at frame 235, and the head shot at frame 313, aligning with witness reports of the first perceptible hit around frames 210-225, a possible missed shot earlier, and the final shot causing forward-then-backward motion.[30][4] Discrepancies arose, such as a minority of witnesses perceiving shots from the grassy knoll (e.g., due to echoes or smoke puffs) or reporting four shots, but the Commission evaluated these against ballistic evidence and found no physical traces—like cartridge cases or positioned snipers—supporting alternative origins, attributing variances to acoustic confusion in the plaza's confines.[4][4]| Key Timeline Elements from Witness and Film Correlation |

|---|

| Event |

| Motorcade departs Love Field |

| Enters Dealey Plaza on Elm Street |

| Shots span |

| Arrives Parkland Hospital |