Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Wealth

View on Wikipedia

Wealth is the abundance of valuable financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions. This includes the core meaning as held in the originating Old English word weal, which is from an Indo-European word stem.[1] The modern concept of wealth is of significance in all areas of economics, and clearly so for growth economics and development economics, yet the meaning of wealth is context-dependent. A person possessing a substantial net worth is known as wealthy. Net worth is defined as the current value of one's assets less liabilities (excluding the principal in trust accounts).[2]

At the most general level, economists may define wealth as "the total of anything of value" that captures both the subjective nature of the idea and the idea that it is not a fixed or static concept. Various definitions and concepts of wealth have been asserted by various people in different contexts.[3] Defining wealth can be a normative process with various ethical implications, since often wealth maximization is seen as a goal or is thought to be a normative principle of its own.[4][5] A community, region or country that possesses an abundance of such possessions or resources to the benefit of the common good is known as wealthy.

The United Nations definition of inclusive wealth is a monetary measure which includes the sum of natural, human, and physical assets.[6][7] Natural capital includes land, forests, energy resources, and minerals. Human capital is the population's education and skills. Physical (or "manufactured") capital includes such things as machinery, buildings, and infrastructure.

History

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2019) |

Around 35,000 years ago Homo sapiens groups began to adopt a more settled lifestyle, as evidenced by cave drawings, burial sites, and decorative objects.[8] Around this time, humans began trading burial-site tools and developed trade networks,[9] resulting in a hunter-gatherer lifestyle.[10] Those who had gathered abundant burial-site tools, weapons, baskets, and food, were considered part of the wealthy.[11][need quotation to verify]

Adam Smith, in his seminal work The Wealth of Nations, described wealth as "the annual produce of the land and labor of the society". This "produce" is, at its simplest, a good or service which satisfies human needs, and wants of utility.

In popular usage, wealth can be described as an abundance of items of economic value, or the state of controlling or possessing such items, usually in the form of money, real estate and personal property. A person considered wealthy, affluent, or rich is someone who has accumulated substantial wealth relative to others in their society or reference group.

In economics, net worth refers to the value of assets owned minus the value of liabilities owed at a point in time.[12] Wealth can be categorized into three principal categories: personal property, including homes or automobiles; monetary savings, such as the accumulation of past income; and the capital wealth of income producing assets, including real estate, stocks, bonds, and businesses. All these delineations make wealth an especially important part of social stratification. Wealth provides some people "safety nets" of protection against unforeseen declines in their living standard in the event of emergency and can be transformed into home ownership, business ownership, or college education by its expenditure.

Wealth has been defined as a collection of things limited in supply, transferable, and useful in satisfying human desires.[13] Scarcity is a fundamental factor for wealth. When a desirable or valuable commodity (transferable good or skill) is abundantly available to everyone, the owner of the commodity will possess no potential for wealth. When a valuable or desirable commodity is in scarce supply, the owner of the commodity will possess great potential for wealth.

'Wealth' refers to some accumulation of resources (net asset value), whether abundant or not. 'Richness' refers to an abundance of such resources (income or flow). A wealthy person, group, or nation thus has more accumulated resources (capital) than a poor one. The opposite of wealth is destitution. The opposite of richness is poverty.

The term implies a social contract on establishing and maintaining ownership in relation to such items which can be invoked with little or no effort and expense on the part of the owner. The concept of wealth is relative and not only varies between societies, but varies between different sections or regions in the same society. A personal net worth of US$10,000 in most parts of the United States would certainly not place a person among the wealthiest citizens of that locale. Such an amount would constitute an extraordinary amount of wealth in impoverished developing countries.

Concepts of wealth also vary across time. Modern labor-saving inventions and the development of the sciences have vastly improved the standard of living in modern societies for even the poorest of people. This comparative wealth across time is also applicable to the future; given this trend of human advancement, it is possible that the standard of living that the wealthiest enjoy today will be considered impoverished by future generations.

Industrialization emphasized the role of technology. Many jobs were automated. Machines replaced some workers while other workers became more specialized. Labour specialization became critical to economic success. Physical capital, as it came to be known, consisting of both the natural capital and the infrastructural capital, became the focus of the analysis of wealth.[citation needed]

Adam Smith saw wealth creation as the combination of materials, labour, land, and technology.[14] The theories of David Ricardo, John Locke, John Stuart Mill, in the 18th century and 19th century built on these views of wealth that we now call classical economics.

Marxian economics (see labor theory of value) distinguishes in the Grundrisse between material wealth and human wealth, defining human wealth as "wealth in human relations"; land and labour were the source of all material wealth. The German cultural historian Silvio Vietta links wealth/poverty to rationality. Having a leading position in the development of rational sciences, in new technologies and in economic production leads to wealth, while the opposite can be correlated with poverty.[15][16]

Global amount

[edit]

The wealth of households worldwide amounts to US$280 trillion (2017). According to the eighth edition of the Global Wealth Report, in the year to mid-2017, total global wealth rose at a rate of 6.4%, the fastest pace since 2012 and reached US$280 trillion, a gain of US$16.7 trillion. This reflected widespread gains in equity markets matched by similar rises in non-financial assets, which moved above the pre-crisis year 2007's level for the first time this year. Wealth growth also outpaced population growth, so that global mean wealth per adult grew by 4.9% and reached a new record high of US$56,540 per adult. Tim Harford has asserted that a small child has greater wealth than the 2 billion poorest people in the world combined, since a small child has no debt.[17]

According to the 2021 global wealth report by McKinsey & Company, the worldwide total net worth is currently at US$514 trillion in 2020, with China being the wealthiest nation with net worth of US$120 trillion.[18][19][20] Another report, by Credit Suisse in 2021, suggests the total wealth of the US exceeded that of China, US$126.3 trillion to US$74.9 trillion.[21]

Philosophical analysis

[edit]In Western civilization, wealth is connected with a quantitative type of thought, invented in the ancient Greek "revolution of rationality", involving for instance the quantitative analysis of nature, the rationalization of warfare, and measurement in economics.[15][16] The invention of coined money and banking was particularly important. Aristotle describes the basic function of money as a universal instrument of quantitative measurement – "for it measures all things [...]" – making things alike and comparable due to a social "agreement" of acceptance.[22] In that way, money also enables a new type of economic society and the definition of wealth in measurable quantities, such as gold and money. Modern philosophers like Nietzsche criticized the fixation on measurable wealth: "Unsere 'Reichen' – das sind die Ärmsten! Der eigentliche Zweck alles Reichtums ist vergessen!" ("Our 'rich people' – those are the poorest! The real purpose of all wealth has been forgotten!")[23]

Economic analysis

[edit]In economics, wealth (in a commonly applied accounting sense, sometimes savings) is the net worth of a person, household, or nation – that is, the value of all assets owned net of all liabilities owed at a point in time. For national wealth as measured in the national accounts, the net liabilities are those owed to the rest of the world.[24] The term may also be used more broadly as referring to the productive capacity of a society or as a contrast to poverty.[25] Analytical emphasis may be on its determinants or distribution.[26]

Economic terminology distinguishes between wealth and income. Wealth or savings is a stock variable – that is, it is measurable at a date in time, for example the value of an orchard on December 31 minus debt owed on the orchard. For a given amount of wealth, say at the beginning of the year, income from that wealth, as measurable over say a year is a flow variable. What marks the income as a flow is its measurement per unit of time, such as the value of apples yielded from the orchard per year.

In macroeconomic theory the 'wealth effect' may refer to the increase in aggregate consumption from an increase in national wealth. One feature of its effect on economic behavior is the wealth elasticity of demand, which is the percentage change in the amount of consumption goods demanded for each one-percent change in wealth.

There are several historical developmental economics points of view on the basis of wealth, such as from Principles of Political Economy by John Stuart Mill, The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, Capital by Karl Marx, etc.[27] Over the history, some of the key underlying factors in wealth creation and the measurement of the wealth include the scalable innovation and application of human knowledge in the form of institutional structure and political/ideological "superstructure", the scarce resources (both natural and man-made), and the saving of monetary assets.

Wealth may be measured in nominal or real values – that is, in money value as of a given date or adjusted to net out price changes. The assets include those that are tangible (land and capital) and financial (money, bonds, etc.). Measurable wealth typically excludes intangible or nonmarketable assets such as human capital and social capital. In economics, 'wealth' corresponds to the accounting term 'net worth', but is measured differently. Accounting measures net worth in terms of the historical cost of assets while economics measures wealth in terms of current values. But analysis may adapt typical accounting conventions for economic purposes in social accounting (such as in national accounts). An example of the latter is generational accounting of social security systems to include the present value projected future outlays considered to be liabilities.[28] Macroeconomic questions include whether the issuance of government bonds affects investment and consumption through the wealth effect.[29]

Environmental assets are not usually counted in measuring wealth, in part due to the difficulty of valuation for a non-market good. Environmental or green accounting is a method of social accounting for formulating and deriving such measures on the argument that an educated valuation is superior to a value of zero (as the implied valuation of environmental assets).[30]

Versus social class

[edit]Social class is not identical to wealth, but the two concepts are related (particularly in Marxist theory),[31] leading to the concept of socioeconomic status. Wealth at the individual or household level refers to value of everything a person or family owns, including personal property and financial assets.[32]

In both Marxist and Weberian theory, class is divided into upper, middle, and lower, with each further subdivided (e.g., upper middle class).[31]

The upper class are schooled to maintain their wealth and pass it to future generations.[33]

The middle class views wealth as something for emergencies and it is seen as more of a cushion. This class comprises people that were raised with families that typically owned their own home, planned ahead and stressed the importance of education and achievement. They earn a significant income and consume many things, typically limiting their savings and investments to retirement pensions and home ownership.[33] Below the middle class, the working class and poor have the least amount of wealth, with circumstances discouraging accumulation of assets.[33]

Distribution

[edit]Although precise data are not available, the total household wealth in the world, excluding the value of human capital, has been estimated at $418.3 trillion (US$418.3 trillion) at the end of the year 2020.[37] For 2018, the World Bank estimated the value of the world's produced capital, natural capital, and human capital to be $1,152 trillion.[38] According to the Kuznets curve, inequality of wealth and income increases during the early phases of economic development, stabilizes and then becomes more equitable.

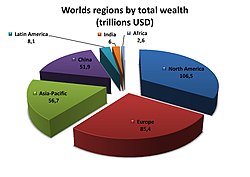

As of 2008[update], about 90% of global wealth is distributed in North America, Europe, and "rich Asia-Pacific" countries,[39] and in 2008, 1% of adults were estimated to hold 40% of world wealth, a number which falls to 32% when adjusted for purchasing power parity.[40] According to Richard H Ropers, the concentration of wealth in the United States is "inequitably distributed".[41]

In 2013, 1% of adults were estimated to hold 46% of world wealth[42] and around $18.5 trillion was estimated to be stored in tax havens worldwide.[43] A fraction of adults have negative net worth, where debt is higher than assets.[44]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "weal". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.). Houghton Mifflin Company. Retrieved February 21, 2009.

- ^ "The Millionaire Next Door". movies2.nytimes.com. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ^ Denis "Authentic Development: Is it Sustainable?", pp. 189–205 in Building Sustainable Societies, Dennis Pirages, ed., M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 978-1563247385. (1996)

- ^ Kronman, Anthony T. (March 1980). "Wealth Maximization as a Normative Principle". The Journal of Legal Studies. 9 (2): 227–242. doi:10.1086/467637. S2CID 153759163.

- ^ Robert L. Heilbroner, 1987 2008. The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 4, pp. 880–883. Brief preview link Archived June 1, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Free exchange: The real wealth of nations". The Economist. June 30, 2012. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- ^ "Inclusive Wealth Report". Ihdp.unu.edu. IHDP. July 9, 2012. Archived from the original on June 30, 2012. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- ^

Beinhocker, Eric D. (2006). The Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Radical Remaking of Economics. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Press. p. 7. ISBN 9781578517770. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

[...] around 35,000 years ago [...] we begin to see the first evidence of a more settled lifestyle, with burial sites, cave drawings, and decorative objects.

- ^

Beinhocker, Eric D. (2006). The Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Radical Remaking of Economics. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Press. p. 7. ISBN 9781578517770. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

During this period, archeologists also begin to see evidence of trading between groups of early humans; the evidence included burial-site tools made from nonlocal materials, seashell jewelry found with noncoastal tribes, and patterns of movement suggesting trading routes.

- ^

Beinhocker, Eric D. (2006). The Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Radical Remaking of Economics. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Press. p. 7. ISBN 9781578517770. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

With permanent settlements, a variety of tools, and the creation of trading networks, our ancestors achieved a level of cultural and economic sophistication that anthropologists refer to as a hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

- ^ Beinhocker, Eric D. (2007). The Origin of Wealth: The Radical Remaking of Economics and What it Means for Business and Society. Harvard Business Review Press; 1st edition.

- ^ "WWE Superstars net worth and salary". Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ "How Wealth is Created". World Book Encyclopedia. Vol. 15. The Grolier Society. 1949. p. 5357.

- ^ Smith, Adam. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations Archived August 1, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Vietta, Silvio (2013). A Theory of Global Civilization: Rationality and the Irrational as the Driving Forces of History. Kindle Ebooks.

- ^ a b Vietta, Silvio (2012). Rationalität. Eine Weltgeschichte. Europäische Kulturgeschichte und Globalisierung. Fink.

- ^ "Global Wealth Report." Archived July 11, 2019, at the Wayback Machine (October 18, 2018). Credit Suisse Research Institute. Credit-Suisse.com. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- ^ "Global wealth surges as China overtakes US to grab top spot: McKinsey report". The Straits Times. November 15, 2021.

- ^ "Global Wealth Surges as China Overtakes U.S. to Grab Top Spot". Bloomberg. November 14, 2021.

- ^ "China overtakes US as world's richest nation as global wealth surges". India Today. November 16, 2021.

- ^ "Research Institute: Global wealth report 2021" (PDF). Credit Suisse. June 2021. Retrieved August 29, 2022.

- ^ Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics. p. 1133a.

- ^ Nietzsche. Werke in drei Bänden. III. p. 419.

- ^ • Paul A. Samuelson and William D. Nordhaus, 2004, 18th ed. Economics, "Glossary of Terms."

• Nancy D. Ruggles, 1987. "social accounting" The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 4, pp. 377–382, [380]. - ^ • Adam Smith, 1776. The Wealth of Nations.

• David S. Landes, 1998. The Wealth and Poverty of Nations. Review. Archived October 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

• Partha Dasgupta, 1993. An Inquiry into Well-Being and Destitution. Description Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine and review. Archived December 15, 2018, at the Wayback Machine - ^ • John Bates Clark, 1902. The Distribution of Wealth Analytical Table of Contents.

• E.N. Wolff, 2002. "Wealth Distribution" International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, pp. 16394–16401. Abstract.

• Robert L. Heilbroner, 1987. [2008]). The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 4, pp. 880–883. Brief preview link Archived June 1, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. - ^ Charles Tuttle, The Wealth Concept. A Study in Economic Theory, Source: The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science , Apr., 1891, Vol. 1 (Apr., 1891), pp. 615–634, Published by: Sage Publications, Inc. in association with the American Academy of Political and Social Science, JSTOR 1008953

- ^ • Jagadeesh Gokhale, 2008. "Generational accounting." The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract Archived October 2, 2011, at the Wayback Machine and uncorrected proof.

• Laurence J. Kotlikoff, 1992, Generational Accounting. Free Press. - ^ Robert J. Barro, 1974. "Are Government Bonds Net Wealth?", Journal of Political Economy, 8(6), pp. 1095–1111. Archived June 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ • Sjak Smulders, 2008. "green national accounting" The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract. Archived May 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

• United States National Research Council, 1994. Assigning Economic Value to Natural Resources, National Academy Press. Chapter-preview links. Archived June 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine - ^ a b Grant, J. Andrew (2001). "class, definition of". In Jones, R.J. Barry (ed.). Routledge Encyclopedia of International Political Economy: Entries A–F. Taylor & Francis. p. 161. ISBN 978-0415243506.

- ^ Team, The Investopedia. "Wealth Definition". Investopedia. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c Sherraden, Michael. Assets and the Poor: A New American Welfare Policy. Armonk: M. E. Sharpe, Inc., 1991.

- ^ Fig. 2 of Sullivan, Briana (July 2025). "Wealth of Households: 2023 (P70BR-211)" (PDF). US Census Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 26, 2025.

- ^ Sullivan, Brianna; Hays, Donald; Bennett, Neil (June 2023). "The Wealth of Households: 2021 / Current Population Reports / P70BR-183" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. p. 5 (Figure 2). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 24, 2024.

- ^ Sullivan, Briana (July 2025). "Wealth of Households: 2023 (P70BR-211)" (PDF). US Census Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 26, 2025.

- ^ "The Global Wealth Report". Credit Suisse.

- ^ The Changing Wealth of Nations, 2021. World Bank Group. October 27, 2021. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-1590-4. hdl:10986/36400. ISBN 978-1-4648-1590-4. S2CID 244394817.

- ^ James B. Davies, Susanna Sandström, Anthony Shorrocks, and Edward N. Wolff. (2008). The World Distribution of Household Wealth, p8 Archived October 16, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. UNU-WIDER.

- ^ James B. Davies, Susanna Sandström, Anthony Shorrocks, and Edward N. Wolff. (2008). The World Distribution of Household Wealth Archived October 16, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. UNU-WIDER.

- ^ Ropers, Richard H, Ph.D. Persistent Poverty: The American Dream Turned Nightmare. New York: Insight Books, 1991.

- ^ "Global Wealth Report 2013". Archived from the original on February 14, 2015. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- ^ "Tax on the 'private' billions now stashed away in havens enough to end extreme world poverty twice over". Oxfam International. May 22, 2013. Archived from the original on December 23, 2015. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- ^ Dräger, Jascha; Pforr, Klaus; Müller, Nora (2023). "Why Net Worth Misrepresents Wealth Effects and What to Do About It" (PDF). Sociological Science. 10. Society for Sociological Science: 534–558. doi:10.15195/v10.a19. ISSN 2330-6696. Retrieved July 19, 2025.

Further reading

[edit]- Alfani, Guido (2023). As Gods Among Men: A History of the Rich in the West. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-22712-2.

- Lee, Dwight R. (2008). "Wealth and Poverty". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Cato Institute. pp. 537–539. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n326. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- Wiedmann, Thomas; Lenzen, Manfred; Keyßer, Lorenz T.; Steinberger, Julia K. (2020). "Scientists' warning on affluence". Nature Communications. 11 (3107): 3107. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.3107W. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-16941-y. PMC 7305220. PMID 32561753.

Wealth

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Measurement

Conceptual Definition

Wealth, in economic analysis, constitutes the net accumulation of assets exceeding liabilities, representing an individual's or entity's command over resources that can sustain or enhance future consumption and production. This encompasses tangible holdings such as land, buildings, and physical commodities, alongside intangible forms including financial instruments, patents, and claims on future earnings.[1][2] Unlike income, which measures periodic resource inflows, wealth functions as a static stock, embodying stored value derived from prior savings, investments, or transfers rather than ongoing earnings.[3] From a foundational perspective, wealth emerges as scarce goods or assets yielding utility—services or benefits for which individuals willingly exchange value—thereby enabling discretionary control over economic outcomes.[8] Economists quantify this conceptually as the discounted present value of prospective consumption streams, underscoring wealth's role in buffering against uncertainty and facilitating intertemporal choices, such as deferring gratification for compounded returns.[7] This definition prioritizes productive potential over nominal aggregates, distinguishing wealth from transient riches by its capacity to generate sustained utility amid scarcity.[9] Critically, conceptualizations must account for contextual variances: in market economies, wealth correlates with marketable claims, yet broader interpretations include human capital or natural endowments, though these evade precise valuation due to non-excludability and depreciation challenges.[8] Empirical assessments, such as those tracking household balance sheets, reveal wealth's concentration as a driver of inequality, yet its accumulation fundamentally traces to voluntary exchanges and risk-bearing rather than zero-sum redistribution.[2]Measurement Methods and Challenges

Wealth is primarily measured as net worth, defined as the current market value of an individual's or household's assets minus liabilities at a specific point in time. Assets encompass non-financial items such as real estate, vehicles, and valuables, alongside financial holdings like bank deposits, equities, bonds, and private pensions; liabilities include mortgages, consumer debts, and other obligations. This stock measure contrasts with income, which captures flows over time, though the two are sometimes conflated in public discourse.[10] Household surveys form the core method for collecting micro-level data, involving direct respondent reports on balance sheets via structured interviews, often using computer-assisted techniques for consistency checks. Examples include the U.S. Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), conducted triennially by the Federal Reserve since 1983, which oversamples high-wealth areas to capture the upper tail; the European Central Bank's Household Finance and Consumption Survey (HFCS), covering euro area countries with harmonized questionnaires; and national efforts like Canada's Survey of Financial Security. In countries with robust administrative systems, such as Nordic nations, register data from tax authorities and property records supplement or replace surveys, providing near-complete coverage of taxable assets and debts. Global aggregates, as in the UBS Global Wealth Report, integrate these micro sources with national accounts data, applying distributional assumptions like Pareto interpolation for the upper tail where surveys underperform.[11] Valuation relies on market prices where possible, with self-estimates or indexed costs for illiquid assets like primary residences or closely held businesses. Measuring the top wealth tail poses acute challenges, as household surveys systematically underrepresent the affluent due to non-response, deliberate underreporting, and sampling frames that miss private or offshore holdings.[12] [13] Wealthy respondents often refuse participation or provide incomplete data, leading to downward-biased inequality estimates; for instance, administrative-tax hybrids in the U.S. reveal SCF undercounts of top-1% wealth by factors of 2-3 times compared to Forbes billionaire lists or estate multipliers.[14] In low- and middle-income countries, informal economies exacerbate gaps, with unrecorded assets like unregistered land or livestock evading capture.[14] Valuation inconsistencies further complicate accuracy, particularly for non-tradable assets: self-reported home values can deviate 20-30% from appraisals due to recall bias or optimism, while private business equity—often 30-50% of top household wealth—relies on subjective owner estimates without arm's-length transactions. Pension wealth, including defined-benefit plans, requires actuarial projections prone to assumption errors, and liabilities like contingent debts (e.g., guarantees) are frequently omitted. Cross-country comparability suffers from divergent definitions, such as inclusion of human capital or state pensions, and exchange rate volatility distorts global rankings when using market versus purchasing power parity conversions. Privacy regulations and respondent fatigue yield high item non-response rates (e.g., over 20% for bonds or foreign assets), necessitating imputation models that introduce variance. These issues underscore reliance on hybrid methods, yet even advanced approaches like those in UBS reports acknowledge modeling uncertainties for 20-30% of global wealth estimates in data-sparse regions.[11]Historical Evolution

Ancient and Pre-Industrial Periods

In ancient Mesopotamia, around 3100–2500 B.C., wealth primarily derived from agricultural surplus along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, supplemented by extensive trade networks extending thousands of miles for resources like wool, lapis lazuli, and metals.[15] Silver emerged as a standard unit of value alongside barley, facilitating economic transactions recorded on clay tablets, while palaces and temples centralized redistribution through credit systems and labor mobilization.[16][17] This structure concentrated wealth among elites, with temples specifying production quotas for goods like spears or pottery to sustain temple economies.[18] In ancient Egypt, pharaonic control over Nile floodplain agriculture generated wealth through state-imposed taxes and estate management, funding monumental projects such as pyramids and temples from the Old Kingdom onward (c. 2686–2181 B.C.).[19] Temples amassed vast landholdings and resources, functioning as economic hubs that employed workers and traded goods, with pharaohs owning key productive assets to maintain social order and military strength.[20][21] Wealth inequality was pronounced, as evidenced by elite tombs filled with gold and imported luxuries, contrasting with peasant subsistence farming. During classical antiquity, Greek city-states from the 5th century B.C. emphasized private property rights, with wealth accumulated through land ownership, olive and wine production, and maritime trade; Athenian elites, for instance, invested in estates valued at 1,000–2,000 drachmas.[22][23] In the Roman Empire (27 B.C.–476 A.D.), conquest enabled vast accumulations of land, slaves, and coinage, with private banking (nummularii) handling deposits and loans; social tables indicate extreme inequality, where the top 1% controlled disproportionate shares compared to later pre-industrial societies.[24][25] Medieval Europe (c. 500–1500 A.D.) operated under feudal land tenure, where kings granted fiefs to vassals in exchange for military service, making land the principal form of wealth extracted via peasant labor and manorial dues.[26] Lords derived income from villein payments and rights over resources, fostering hierarchical inequality tied to arable output rather than liquid assets.[27] In parallel, pre-industrial Asian empires sustained large-scale wealth; India's Mughal era (1526–1857) accounted for about 24% of global GDP in 1700 through textile exports and agrarian taxation, while China's imperial systems relied on rice paddies and Silk Road commerce, both amplifying elite land and trade monopolies.[28] Across these societies, post-agricultural inequality intensified within 1,500 years, driven by elite control of scalable assets like land and coerced labor, as house sizes and grave goods reveal widening gaps from egalitarian hunter-gatherer baselines.[29][30]Industrial Revolution to 20th Century

The Industrial Revolution, commencing in Britain around 1760 with innovations in textiles, steam power, and iron production, marked the onset of sustained capital accumulation through mechanized production and factory systems, enabling unprecedented wealth generation via scalable manufacturing and trade expansion.[31] This period saw Britain's GDP per capita rise from approximately £1,200 in 1700 to £2,300 by 1820 (in 1990 international dollars), reflecting initial capital investments in machinery and infrastructure that outpaced population growth.[32] Empirical evidence from macroeconomic data indicates that technical change and capital deepening drove this growth, with savings rates increasing as industrial profits were reinvested, though living standards for the working class lagged initially due to wage stagnation amid rapid urbanization.[33] By the mid-19th century, the revolution spread to continental Europe and the United States, fueled by railway networks and steamships that lowered transport costs and integrated markets, amplifying wealth creation in sectors like steel and coal. In the U.S., national wealth expanded from $1.2 billion in 1805 to $20 billion by 1850, driven by canal and rail investments that facilitated resource extraction and commerce.[34] Europe's industrialization similarly concentrated capital in urban centers; for instance, France's wealth-to-income ratio climbed as bourgeois investors funded heavy industry, though unevenly across regions due to varying institutional adoption of property rights and banking.[35] Wealth became highly concentrated among industrial entrepreneurs, exemplified by figures like Andrew Carnegie, whose sale of Carnegie Steel to J.P. Morgan in 1901 yielded $480 million—equivalent to about 0.6% of U.S. GDP at the time—and John D. Rockefeller, who amassed a fortune controlling 90% of American oil refining by the 1880s through vertical integration and economies of scale.[36] These "robber barons" or captains of industry leveraged monopolistic practices and technological efficiencies to accumulate personal estates rivaling small nations' GDPs, with Carnegie's wealth peaking at over $300 million by 1911 after philanthropy adjustments.[37] Such accumulations stemmed from causal chains of innovation—e.g., Bessemer steel process enabling mass production—coupled with limited antitrust regulation, though critics like contemporary reformers attributed excesses to rent-seeking rather than pure value creation.[38] Inequality metrics underscore this era's divergence: in Europe, the top 10% held over 80% of national wealth in 1810, rising through the 19th century as industrial returns favored capital owners over labor.[39] In the U.S., the wealth Gini coefficient increased from 0.44 in 1774 to 0.53 by 1860, with the top 1% capturing nearly half of property income by the Gilded Age (circa 1870–1900), reflecting unequal gains from industrialization where skilled inventors and financiers outpaced agrarian and proletarian classes.[34] Global estimates show Western per-adult wealth surging from subsistence levels pre-1800 to multiples higher by 1900, while non-industrial regions stagnated, widening inter-regional gaps due to technology diffusion barriers and colonial resource drains.[40] Into the early 20th century, mass production via assembly lines—pioneered by Henry Ford in 1913—further propelled wealth via automobiles and electrification, with U.S. total wealth reaching $200 billion by 1920 amid corporate consolidations.[41] However, events like World War I (1914–1918) and the Great Depression (1929–1939) eroded fortunes through inflation, destruction, and policy shocks, temporarily compressing top wealth shares; Europe's top 1% wealth fell from 55–60% pre-1914 to under 40% by 1930 in some nations due to wartime capital levies and hyperinflation.[42] Despite disruptions, underlying mechanisms of savings, reinvestment, and innovation sustained aggregate wealth growth, setting stages for post-war expansions, with global wealth-to-GDP ratios stabilizing around 4–5 times income by mid-century.[43]Post-1945 Developments and Recent Trends

Following World War II, wealth destruction in Europe and Asia from wartime devastation and hyperinflation led to a temporary compression of wealth inequality, with top wealth shares falling sharply in affected countries due to physical asset losses, capital flight, and progressive taxation policies. In the United States, spared major destruction, household wealth relative to national income stabilized at around 300% in the postwar decades, down from 400% in the early 20th century, reflecting broad-based accumulation amid economic expansion. Real GDP in the U.S. grew by approximately 37% from 1945 to 1960, driven by consumer spending, suburbanization, and increased home ownership rates, which rose from 44% in 1940 to 62% by 1960, bolstering middle-class net worth through real estate and durable goods.[44][45][46] Western Europe's reconstruction, aided by the Marshall Plan (disbursing $13 billion from 1948 to 1952), spurred industrial recovery and wealth rebuilding, with annual GDP growth averaging 4-5% in the 1950s and 1960s across the region. Globally, the capital-output ratio—a proxy for wealth relative to income—dropped to about 300% by 1950 amid war's leveling effects, but began recovering as savings rates rose and institutions like Bretton Woods stabilized trade and finance. From the 1970s onward, wealth inequality trends reversed in advanced economies: U.S. top 1% wealth share climbed from 22% in 1978 to over 30% by 2012, fueled by financial deregulation, stock market gains, and executive compensation structures, while total household wealth expanded to 450-500% of income by the 2000s.[47][48][49] The late 20th century saw accelerating global wealth growth through globalization and emerging market integration. Total global wealth, estimated at roughly $100-150 trillion in 1980 (in constant terms), surged with China's economic reforms post-1978 and India's liberalization in 1991, adding trillions in household assets via urbanization and manufacturing exports. By 2000, global wealth reached approximately $113 trillion, expanding to $195 trillion by 2011—a 72% increase—largely from rising property and equity values in Asia and the West. Since 1995, average wealth per adult has grown at 3.2% annually, with non-Western regions contributing disproportionately; for instance, Asia's share of global wealth rose from 20% in 2000 to over 30% by 2020, driven by population growth and per capita gains in countries like China, where median wealth per adult increased from under $1,000 in 1990 to $25,000 by 2020.[50][51] Recent trends since the 2008 financial crisis highlight asset price inflation from quantitative easing and low interest rates, which amplified wealth for asset owners: U.S. household net worth doubled from $60 trillion in 2009 to over $140 trillion by 2022, with the top 10% capturing 70% of gains via stocks and real estate. Globally, total wealth hit $463 trillion by 2023, up from $360 trillion pre-COVID, though growth slowed to 1-2% annually in 2022-2023 amid inflation and geopolitical tensions; the number of millionaires rose to 62 million adults by 2023, concentrated in the U.S. (22 million) and Europe. Despite rising top-end concentration—the global top 1% held 45-50% of wealth in the 2010s—median wealth per adult climbed 20-30% in emerging economies from 2010 to 2020, reflecting broader access to credit and property, though bottom 50% shares remained under 2% due to limited capital ownership. Technological innovation in fintech and digital assets, including cryptocurrencies reaching $2 trillion market cap by 2021, has introduced new wealth channels, primarily benefiting skilled investors in high-income nations.[52][11][53]Mechanisms of Wealth Creation

Entrepreneurship and Innovation

Entrepreneurship entails the identification of unmet market needs, the mobilization of resources, and the commercialization of novel ideas or processes, thereby generating surplus value that manifests as wealth for founders, investors, and economies at large. Empirical analyses indicate that entrepreneurs create new wealth by transforming innovations into scalable enterprises, often outpacing established firms in productivity gains and market disruption. For example, a study using U.S. Panel Study of Income Dynamics data found that self-employment significantly contributes to wealth concentration and mobility, with entrepreneurial income explaining a substantial portion of high-net-worth transitions among households.[54] This process relies on risk-taking and resource reallocation, where successful ventures capture economic rents from efficiency improvements or consumer surplus previously untapped. Innovation, as the engine of entrepreneurship, propels wealth creation through technological and organizational advancements that enhance productivity and expand output frontiers. Joseph Schumpeter's concept of "creative destruction" posits that innovations supplant obsolete technologies and business models, fostering sustained growth despite short-term displacements; evidence from macroeconomic models and historical data corroborates that this dynamic accounts for a core component of long-term economic expansion, with barriers to entry amplifying its effects on wealth redistribution toward innovators.[55] In the United States, small businesses—predominantly entrepreneurial—generated 44% of economic activity and two-thirds of net new jobs as of 2014, underscoring their role in capital formation and GDP contributions.[56] Cross-country regressions further reveal that entrepreneurial activity correlates positively with per capita GDP in high-income nations, where attitudes favoring risk and opportunity recognition drive output per worker.[57] Prominent cases illustrate these mechanisms: Jeff Bezos launched Amazon in 1994 as an online bookstore, leveraging e-commerce innovation to disrupt retail; by 2023, the company's revenue exceeded $574 billion, elevating Bezos's net worth to approximately $194 billion and creating ancillary wealth via stock appreciation for employees and shareholders.[58] Similarly, Elon Musk's ventures, including Tesla founded in 2003, commercialized electric vehicle and battery technologies, yielding a market capitalization over $1 trillion by 2025 and Musk's wealth surpassing $250 billion, while spurring industry-wide investments in sustainable energy.[59] These outcomes stem from first-mover advantages and network effects, though success rates remain low—data from U.S. publicly traded firms show only a fraction of startups achieve outsized returns, with entrepreneurial activity nonetheless proving a net positive for aggregate wealth via spillovers like knowledge diffusion and competition-induced efficiencies.[60] Critically, institutional factors such as access to capital and regulatory environments modulate these effects; barriers disproportionately hinder certain demographics, yet empirical evidence attributes primary wealth gaps to entry frictions rather than inherent traits, with entrepreneurship mitigating income disparities through upward mobility channels.[61] Overall, entrepreneurship and innovation sustain wealth creation by reallocating resources toward higher-value uses, evidenced by their outsized role in historical growth episodes like the Industrial Revolution and modern tech booms, where incremental and radical inventions alike compounded societal prosperity.[62]Capital Accumulation and Investment

Capital accumulation denotes the process by which savings are channeled into additional capital goods—such as machinery, equipment, and infrastructure—to augment productive capacity within an economy.[63] This mechanism, central to classical economic thought, originates from the restraint of immediate consumption in favor of reinvesting surplus output, thereby expanding the means of production over time.[64] In neoclassical frameworks, accumulation equilibrates savings with investment opportunities, where the marginal productivity of capital determines returns and influences wage levels, with empirical models indicating that sustained capital deepening correlates with higher long-run real wages.[65] Investment serves as the operational conduit for accumulation, directing funds into income-generating assets like equities, real estate, and business ventures that yield returns exceeding depreciation and opportunity costs. Historical data from U.S. markets illustrate this dynamic: from 1928 to 2024, stocks delivered an arithmetic average annual return of 11.79% nominally, with geometric means around 9.80%, outpacing bonds (5.28% arithmetic) and bills (3.31% arithmetic), thus enabling compounding to transform initial principal into exponential wealth growth.[66] For example, a $100 investment in the S&P 500 at the start of 1928, with dividends reinvested, would have appreciated to over $1 million by 2024 in nominal terms, underscoring how persistent returns from productive capital deployment underpin individual and aggregate wealth formation.[66] Empirical analyses affirm investment's causal role in wealth disparities and growth, with studies in developing contexts demonstrating that diversified strategies—encompassing equities and fixed assets—significantly elevate household wealth, as measured by net asset increases over multi-year horizons.[67] However, returns exhibit volatility; equities experienced negative annual performance in roughly 30% of years from 1825 to 2019, necessitating risk-adjusted allocation to mitigate drawdowns while preserving accumulation's compounding benefits.[68] Modern extensions, including lifecycle models, highlight financial knowledge as amplifying accumulation, where informed investors achieve higher risk premia through asset selection, though institutional biases in advisory services may distort optimal paths for less affluent savers.[69] In macroeconomic terms, accumulation via investment drives Solow-style growth by shifting the production frontier outward, with cross-country evidence linking higher capital-output ratios to sustained GDP per capita advances, albeit tempered by diminishing returns absent technological progress.[70] Policies fostering secure property rights and low frictional taxes enhance this process by incentivizing reinvestment over hoarding, as evidenced by post-reform surges in capital stock in economies transitioning from central planning.[71]Inheritance, Transfers, and Other Factors

Inheritance constitutes a primary mechanism for wealth transmission across generations, enabling the preservation and compounding of assets without requiring new productive efforts from recipients. In the United States, data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics indicate that approximately 30 percent of households receive an inheritance over their lifetime, with these transfers accounting for nearly 40 percent of their accumulated net worth at that point.[72] Similarly, National Bureau of Economic Research analysis of Survey of Consumer Finances data shows that between 80 and 90 percent of wealth transfers to households consist of inheritances, underscoring their dominance over other forms of bequests.[73] These inflows often occur later in life, amplifying wealth through subsequent investment returns, though empirical evidence suggests recipients typically save about half of inherited amounts while dissipating the rest on consumption or debt reduction.[74] Intergenerational transfers, encompassing both inheritances and inter vivos gifts such as down payments on homes or educational funding, further facilitate wealth accumulation by providing liquidity and opportunities unavailable to those without familial support. In advanced economies, the flow of such transfers has risen notably; for instance, in France, annual inheritance and gift flows increased from 2 percent of national income in 1950 to 15 percent by 2010, reflecting demographic shifts and asset appreciation.[75] United States Federal Reserve studies highlight that these transfers contribute to wealth concentration, with intergenerational transmission explaining a portion of persistent disparities, such as 14 to 26 percent of the racial wealth gap between white and Black families depending on model specifications.[76][77] However, the net effect on inequality is context-dependent: inheritances temporarily reduce relative measures like the Gini coefficient by disproportionately benefiting lower-wealth recipients, but this equalizing impact reverses within a decade as high-wealth heirs leverage transfers more effectively for further accumulation.[78][79] Beyond direct transfers, other factors such as assortative mating—where individuals partner with those of similar socioeconomic status—amplify inherited advantages by pooling resources and enhancing access to networks and opportunities. Federal Reserve analysis of consumer finance surveys reveals that spousal wealth correlations contribute to intergenerational persistence, with children of high-wealth parents more likely to marry into affluent families, thereby sustaining family wealth trajectories independent of individual earnings.[80] Familial provision of non-monetary support, including education funding or business connections, also bolsters wealth creation, though quantitative estimates vary; studies attribute only a modest direct role to such indirect transfers in overall inequality, emphasizing instead their role in enabling higher returns on human and social capital.[81] Rare events like lottery winnings or legal settlements represent negligible contributors on aggregate, affecting far fewer than 1 percent of households meaningfully.[72] Collectively, these elements highlight how non-market mechanisms perpetuate wealth, often countering narratives of purely merit-based accumulation while empirical data cautions against overattributing inequality solely to inheritance flows.[82]Distribution and Inequality

Global and Regional Patterns

Global wealth grew by 4.6% in 2024, following a 4.2% increase in 2023, driven primarily by asset price appreciation and economic expansion in key markets.[4] This growth reflects a concentration of wealth in advanced economies, where financial assets, real estate, and equities predominate, contrasting with lower levels in emerging regions reliant on commodities and human capital.[4] Wealth distribution exhibits stark regional disparities, with the Americas holding 35.9%, EMEA (Europe, Middle East, and Africa) 39.3%, and APAC (Asia-Pacific) 24.8% of global wealth as of December 31, 2024.[83] Within these, North America leads in average wealth per adult at $593,347, followed by Oceania at $496,696 and Western Europe at $287,688, underscoring the role of mature financial systems and high productivity in these areas.[4] Growth rates varied, with the Americas exceeding 11%, while APAC and EMEA lagged below 3% and 0.5%, respectively, highlighting divergent trajectories influenced by policy stability, innovation, and trade dynamics.[4] In North America, the United States accounts for the bulk of wealth, with total private wealth estimated at over $140 trillion, representing about 30% of the global total, fueled by technological innovation and capital markets depth.[84] China's rapid accumulation in APAC has elevated the region's share, though per capita figures remain lower due to population scale and uneven development.[84] Europe benefits from diversified assets and inheritance structures, but faces challenges from demographic aging and regulatory burdens. Emerging regions like Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa hold minimal shares, with median wealth per adult often below $10,000, attributable to institutional weaknesses, political instability, and limited capital formation.[4] These patterns persist despite global integration, as empirical data indicate that secure property rights and rule of law correlate strongly with higher wealth levels across regions.[5]Temporal Trends and Data

Global household wealth has expanded markedly since the late 20th century, driven by economic growth, asset price appreciation, and population increases. According to the UBS Global Wealth Report 2024, total global wealth grew by 4.2% in 2023 to reach an estimated $454 trillion, continuing a recovery from the 2022 downturn and reflecting cumulative annual growth averaging around 5-6% since 2000 in nominal terms.[85] This expansion has been uneven, with advanced economies accounting for the majority of absolute gains, while emerging markets like China contributed disproportionately to the rise in the number of wealthy individuals.[5] The global wealth-to-income ratio surged from approximately 390% of net domestic product in 1980 to over 625% by 2025, indicating accelerated capital accumulation relative to annual output, primarily through real estate and financial assets.[48] Wealth distribution metrics reveal high and persistent inequality, with the global Gini coefficient for wealth estimated at 0.89 as of recent assessments, far exceeding income Gini figures around 0.65-0.70.[6] Historically, within-country wealth inequality compressed in the mid-20th century across Western nations due to wartime destruction of capital, progressive inheritance taxes, and high marginal income tax rates, reducing top 1% wealth shares to lows of 20-25% by the 1970s in countries like the United States and France.[86] From the 1980s onward, deregulation, lower capital taxes, and globalization reversed this trend, elevating top 1% shares to 30-40% by the 2010s in many OECD economies; for instance, in the US, the top 1% wealth share climbed from 22% in 1980 to 32% in 2022.[87] Globally, the top 10% of adults captured about 76% of net personal wealth in 2021, while the bottom 50% held under 2%, a concentration that has remained stable since 2000 despite total wealth tripling.[88] Recent decades show mixed temporal shifts influenced by financial crises and policy responses. The 2008 global financial crisis initially widened gaps as asset values plummeted for leveraged middle-class households, but subsequent quantitative easing and low interest rates boosted equities and housing, disproportionately benefiting the asset-rich top decile.[89] In the US, wealth inequality as measured by the ratio of top-to-middle wealth fell slightly from 2008 peaks, with the wealthiest families' holdings dropping to 71 times middle-class levels by 2022 from 91 times in 2019, amid broader market recoveries.[90] [91] Globally, the proportion of adults with wealth under $10,000 declined from 75% in 2000 to about 40% by 2023, signaling a growing middle tier in Asia and Latin America, though ultra-high-net-worth individuals (over $50 million) saw their numbers rise by over 50% since 2012.[92] Post-2020 pandemic stimulus further concentrated gains at the top, with billionaire wealth surging 99% from 2020 to 2024 amid stock market rallies, while wage earners faced inflation erosion.[89]| Period | Key Global Wealth Trend | Example Metric (Top 1% Share) |

|---|---|---|

| 1910-1970 | Compression in developed nations | US: ~45% to 22%[87] |

| 1980-2000 | Divergence post-deregulation | Global top 10%: Rise to ~70% of wealth[93] |

| 2000-2023 | Stable high concentration with base broadening | Bottom 50%: <2%; adults >$10k: From 25% to 60%[92] |