Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ottawa dialect

View on Wikipedia| Ottawa | |

|---|---|

| Nishnaabemwin, Daawaamwin | |

| Native to | Canada, United States |

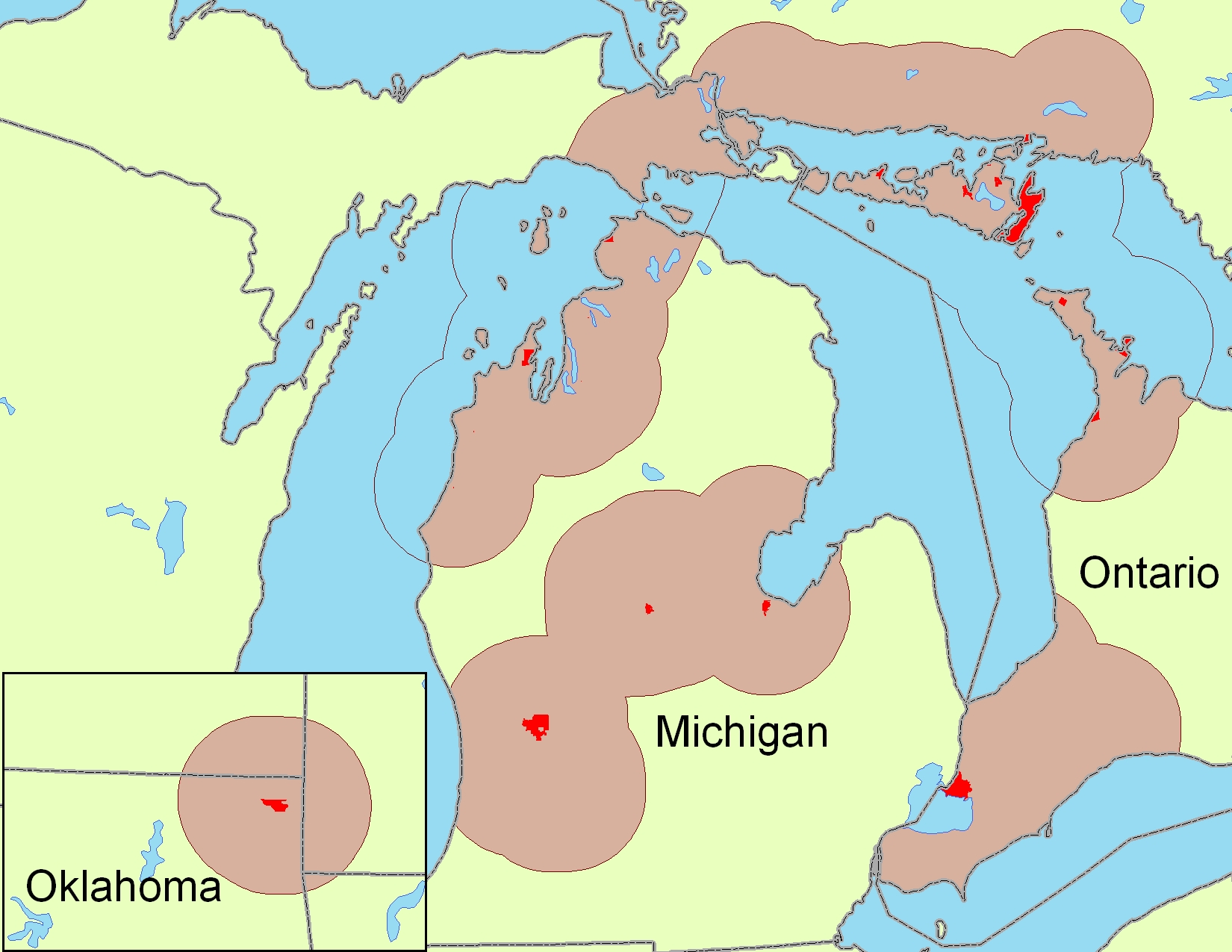

| Region | Ontario, Michigan, Oklahoma |

| Ethnicity | 60,000 Odawa[1] |

Native speakers | 5,108 US: 4,888[2] Canada: 220[3] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | otw |

| Glottolog | otta1242 |

| ELP | Ottawa |

| Linguasphere | (Odawa) 62-ADA-dd (Odawa) |

Ottawa population areas in Ontario, Michigan and Oklahoma. Reserves/Reservations and communities shown in red. | |

Ottawa is classified as Severely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger. | |

| adaawe "to trade" / "to buy and sell" | |

|---|---|

| Person | Daawaa / Odaawaa Ojibwe Nishnaabe |

| People | Daawaak / Odaawaag Ojibweg Nishnaabeg |

| Language | Daawaamwin / Odaawaamwin Ojibwemowin Nishnaabemwin Hand Talk |

| Country | Daawaaying / Odaawaaying Daawaaw’kii / Odaawaaw’kii Ojibwewaki Nishnaabew’kii |

Ottawa or Odawa is a dialect of the Ojibwe language spoken by the Odawa people in southern Ontario in Canada, and northern Michigan in the United States. Descendants of migrant Ottawa speakers live in Kansas and Oklahoma. The first recorded meeting of Ottawa speakers and Europeans occurred in 1615 when a party of Ottawas encountered explorer Samuel de Champlain on the north shore of Georgian Bay. Ottawa is written in an alphabetic system using Latin letters, and is known to its speakers as Nishnaabemwin 'speaking the native language' or Daawaamwin 'speaking Ottawa'.

Ottawa is one of the Ojibwe dialects that has undergone the most language change, although it shares many features with other dialects. The most distinctive change is a pervasive pattern of vowel syncope that deletes short vowels in many words, resulting in significant changes in their pronunciation. This and other innovations in pronunciation, in addition to changes in word structure and vocabulary, differentiate Ottawa from other dialects of Ojibwe.

Like other Ojibwe dialects, Ottawa grammar includes animate and inanimate noun gender, subclasses of verbs that are dependent upon gender, combinations of prefixes and suffixes that are connected with particular verb subclasses, and complex patterns of word formation. Ottawa distinguishes two types of third person in sentences: proximate, indicating a noun phrase that is emphasized in the discourse, and obviative, indicating a less prominent noun phrase. Ottawa has a relatively flexible word order compared with languages such as English.

Ottawa speakers are concerned that their language is endangered as the use of English increases and the number of fluent speakers declines. Language revitalization efforts include second language learning in primary and secondary schools.

Classification

[edit]Ottawa is known to its speakers as Nishnaabemwin 'speaking the native language' (from Anishinaabe 'native person' + verb suffix -mo 'speak a language' + suffix -win 'nominalizer', with regular deletion of short vowels); the same term is applied to the Eastern Ojibwe dialect.[4] The corresponding term in other dialects is Anishinaabemowin.[5] Daawaamwin (from Odaawaa 'Ottawa' + verb suffix -mo 'speak a language' + suffix -win 'nominalizer', with regular deletion of short vowels) 'speaking Ottawa' is also reported in some sources.[6] The name of the Canadian capital Ottawa is a loanword that comes through French from odaawaa, the self-designation of the Ottawa people.[7][8] The earliest recorded form is Outaouan, in a French source from 1641.[9]

Ottawa is a dialect of the Ojibwe language, which is a member of the Algonquian language family.[10] The varieties of Ojibwe form a dialect continuum, a series of adjacent dialects spoken primarily in the area surrounding the Great Lakes as well as in the Canadian provinces of Quebec, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan, with smaller outlying groups in North Dakota, Montana, Alberta, and British Columbia. Mutual intelligibility is the linguistic criterion used to distinguish languages from dialects.[11][12] In straightforward cases, varieties of language that are mutually intelligible are classified as dialects, while varieties of speech that are not mutually intelligible are classified as separate languages.[13] Linguistic and social factors may result in inconsistencies in how the terms language and dialect are used.[14]

Languages spoken in a series of dialects occupying adjacent territory form a dialect continuum or language complex, with some of the dialects being mutually intelligible while others are not. Adjacent dialects typically have relatively high degrees of mutual intelligibility, but the degree of mutual intelligibility between nonadjacent dialects varies considerably. In some cases, speakers of nonadjacent dialects may not understand each other's speech.[14][15]

A survey conducted during the 1980s and 1990s found that the differences between Ottawa, the Severn Ojibwe dialect spoken in northwestern Ontario and northern Manitoba, and the Algonquin dialect spoken in western Quebec result in low levels of mutual intelligibility.[16] These three dialects "show many distinct features, which suggest periods of relative isolation from other varieties of Ojibwe."[17] Because the dialects of Ojibwe are at least partly mutually intelligible, Ojibwe is conventionally considered to be a single language with a series of adjacent dialects.[18] Taking account of the low mutual intelligibility of the most strongly differentiated dialects, an alternative view is that Ojibwe "could be said to consist of several languages",[18] forming a language complex.[19]

Geographic distribution

[edit]The Ottawa communities for which the most detailed linguistic information has been collected are in Ontario. Extensive research has been conducted with speakers from Walpole Island in southwestern Ontario near Detroit, and Wikwemikong on Manitoulin Island in Lake Huron. South of Manitoulin Island on the Bruce Peninsula are Cape Croker and Saugeen, for which less information is available.[20] The dialect affiliation of several communities east of Lake Huron remains uncertain. Although "the dialect spoken along the eastern shore of Georgian Bay" has been described as Eastern Ojibwe, studies do not clearly delimit the boundary between Ottawa and Eastern Ojibwe.[21][16][22]

Other Canadian communities in the Ottawa-speaking area extend from Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario along the north shore of Lake Huron: Garden River,[23] Thessalon,[24] Mississauga (Mississagi River 8 Reserve,[25][26] Serpent River,[27][28] Whitefish River,[24][29] Mattagami,[25] and Whitefish Lake.[24] In addition to Wikwemikong, Ottawa communities on Manitoulin Island are, west to east: Cockburn Island,[30] Sheshegwaning,[27][31] West Bay,[24] Sucker Creek,[24][32] and Sheguiandah.[27][33] Other Ottawa communities in southwestern Ontario in addition to Walpole Island are: Sarnia, Stoney and Kettle Point, and Caradoc (Chippewas of the Thames), near London, Ontario.[34][35]

Communities in Michigan where Ottawa linguistic data has been collected include Peshawbestown, Harbor Springs, Grand Rapids, Mount Pleasant, Bay City, and Cross Village.[34][36] The descendants of migrant Ottawas live in Kansas and Oklahoma;[37][38] available information indicates only three elderly speakers in Oklahoma as of 2006.[39]

Reliable data on the total number of Ottawa speakers is not available, in part because Canadian census data does not identify the Ottawa as a separate group.[40] One report suggests a total of approximately 8,000 speakers of Ottawa in the northern United States and southern Ontario out of an estimated total population of 60,000.[41] A field study conducted during the 1990s in Ottawa communities indicates that Ottawa is in decline, noting that "Today too few children are learning Nishnaabemwin as their first language, and in some communities where the language was traditionally spoken, the number of speakers is very small."[42] Formal second-language classes attempt to reduce the impact of declining first-language acquisition of Ottawa.[43]

Population movements

[edit]At the time of first contact with Europeans in the early 17th century, Ottawa speakers resided on Manitoulin Island, the Bruce Peninsula, and probably the north and east shores of Georgian Bay. The northern area of the Lower Peninsula of Michigan has also been a central area for Ottawa speakers since the arrival of Europeans.[44]

Since the arrival of Europeans, the population movements of Ottawa speakers have been complex,[44] with extensive migrations and contact with other Ojibwe groups.[45] Many Ottawa speakers in southern Ontario are descended from speakers of the Southwestern Ojibwe dialect (also known as "Chippewa") who moved into Ottawa-speaking areas during the mid-19th century. Ottawa today is sometimes referred to as Chippewa or Ojibwe by speakers in these areas.[36] As part of a series of population displacements during the same period, an estimated two thousand American Potawatomi speakers from Wisconsin, Michigan and Indiana moved into Ottawa communities in southwestern Ontario.[46] The non-Ottawa-speaking Ojibwes who moved to these areas shifted to speaking Ottawa, as did the Potawatomi migrants. As a result of the migrations, Ottawa came to include Potawatomi and Ojibwe loanwords.[47]

Two subdialects of Ottawa arise from these population movements and the subsequent language shift. The subdialects are associated with the ancestry of significant increments of the populations in particular communities and differences in the way the language is named in those locations.[48] On Manitoulin Island, where the population is predominantly of Ottawa origin, the language is called Ottawa, and has features that set it off from other communities that have significant populations of Southwestern Ojibwe (Chippewa) and Potawatomi descent. In the latter communities, the language is called Chippewa but is still clearly Ottawa. Dialect features found in "Ottawa Ottawa" that distinguish it from "Chippewa Ottawa" include deletion of the sounds w and y between vowels, glottalization of w before consonants,[49] changes in vowel quality adjacent to w,[50] and distinctive intonation.[48][51]

Phonology

[edit]Ottawa has seventeen consonants and seven oral vowels; there are also long nasal vowels whose phonological status is unclear.[52] In this article, Ottawa words are written in the modern orthography described below, with phonetic transcriptions in brackets using the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) as needed.[53]

The most prominent feature of Ottawa phonology is vowel syncope, in which short vowels are deleted, or in certain circumstances reduced to schwa [ə], when they appear in metrically defined weak syllables. Notable effects of syncope are:[54]

- Differences in pronunciation between Ottawa and other dialects of Ojibwe, resulting in a lower degree of mutual intelligibility.[55]

- Creation of new consonant clusters that do not occur in other dialects, through deletion of short vowels between two consonants.[56]

- Adjustments in the pronunciation of consonant sequences.[57]

- New forms of the person prefixes that occur on nouns and verbs.[58]

- Variability in the pronunciation of words that contain vowels subject to syncope, as speakers frequently have more than one way of pronouncing them.[59]

Consonants

[edit]The table of consonants uses symbols from the modern orthography with the corresponding symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) following where the two vary, or to draw attention to a particular property of the sound in question.[60]

| Bilabial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Postalveolar/ Palatal |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ||||

| Stop | Lenis | b | d | dʒ ⟨j⟩ | g | ʔ ⟨h⟩ |

| Fortis | pːʰ ⟨p⟩ | tːʰ ⟨t⟩ | tʃːʰ ⟨ch⟩ | kːʰ ⟨k⟩ | ||

| Fricative | Lenis | z | ʒ ⟨zh⟩ | |||

| Fortis | f[a] | sː ⟨s⟩ | ʃː ⟨sh⟩ | |||

| Approximant | r,[a] l[a] | j ⟨y⟩ | w | |||

The plosive, fricative, and affricate consonants are divided into two sets, referred to as fortis and lenis. Fortis (or "strong") consonants are typically distinguished from lenis (or "weak") consonants by features such as greater duration or length, are voiceless where lenis consonants are typically voiced, and may be aspirated.[62][63] In Ottawa, each fortis consonant is matched to a corresponding lenis consonant with the same place of articulation and manner of articulation. Ottawa fortis consonants are voiceless and phonetically long,[64] and are aspirated in most positions: [pːʰ], [tːʰ], [kːʰ], [tʃːʰ]. When following another consonant they are unaspirated or weakly articulated.[65] The lenis consonants are typically voiced between vowels and word-initially before a vowel, but are devoiced in word-final position. The lenis consonants are subject to other phonological processes when adjacent to fortis consonants.[66]

Labialized stop consonants [ɡʷ] and [kʷ], consisting of a consonant with noticeable lip rounding, occur in the speech of some speakers. Labialization is not normally indicated in writing, but a subscript dot is utilized in a widely used dictionary of Ottawa and Eastern Ojibwe to mark labialization: ɡ̣taaji 'he is afraid' and aaḳzi 'he is sick'.[67]

Vowels

[edit]Ottawa has seven oral vowels, four long and three short. There are four long nasal vowels whose status as either phonemes or allophones (predictable variants) is unclear.[68] The long vowels /iː, oː, aː/ are paired with the short vowels /i, o, a/,[50] and are written with double symbols ⟨ii⟩, ⟨oo⟩, ⟨aa⟩ that correspond to the single symbols used for the short vowels ⟨i⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨a⟩. The long vowel /eː/ does not have a corresponding short vowel, and is written with a single e.[69] The phonological distinction between long and short vowels plays a significant role in Ottawa phonology, as only short vowels can be metrically weak and undergo syncope. Long vowels are always metrically strong and never undergo deletion.[70]

The table below gives the orthographic symbol and the primary phonetic values for each vowel.[71]

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short | Long | Short | Long | |

| High | ⟨i⟩ ɪ | ⟨ii⟩ iː | ||

| Mid | ⟨e⟩ eː | ⟨o⟩ ʊ~ə | ⟨oo⟩ oː~uː | |

| Low | ⟨a⟩ ə~ɑ | ⟨aa⟩ ɑː | ||

The long nasal vowels are iinh ([ĩː]), enh ([ẽː]), aanh ([ãː]), and oonh ([õː]). They most commonly occur in the final syllable of nouns with diminutive suffixes or words with a diminutive connotation,[72] as well as in the suffix (y)aanh ([-(j)ãː]) 'first person (Conjunct) Animate Intransitive'.[73] Orthographically the long vowel is followed by word-final ⟨nh⟩ to indicate that the vowel is nasal; while n is a common indicator of nasality in many languages such as French, the use of ⟨h⟩ is an orthographic convention and does not correspond to an independent sound.[74] One analysis treats the long nasal vowels as phonemic,[75] while another treats them as derived from sequences of long vowel followed by /n/ and underlying /h/; the latter sound is converted to [ʔ] or deleted.[76] A study of the Southwestern Ojibwe (Chippewa) dialect spoken in Minnesota describes the status of the analogous vowels as unclear, noting that while the distribution of the long nasal vowels is restricted, there is a minimal pair distinguished only by the nasality of the vowel: giiwe [ɡiːweː] 'he goes home' and giiwenh [ɡiːwẽː] 'so the story goes'.[77] Other discussions of Ottawa phonology and phonetics are silent on the issue.[74][78]

| Nasal Vowel | Example | English |

|---|---|---|

| iinh | kiwenziinh | 'old man' |

| wesiinh | '(small) animal' | |

| enh | mdimooyenh | 'old woman' |

| nzhishenh | 'my uncle' | |

| aanh | bnaajaanh | 'nestling' |

| oonh | zhashkoonh | 'muskrat' |

| boodoonh | 'polliwog, tadpole' |

Grammar

[edit]

Ottawa shares the general grammatical characteristics of the other dialects of Ojibwe. Word classes include nouns, verbs, grammatical particles, pronouns, preverbs, and prenouns.[80]

Ottawa grammatical gender classifies nouns as either animate or inanimate.[81] Transitive verbs encode the gender of the grammatical object, and intransitive verbs encode the gender of the grammatical subject, creating a set of four verb subclasses.[82] The distinction between the two genders also affects verbs through agreement patterns for number and gender.[83] Similarly, demonstrative pronouns agree in gender with the noun they refer to.[84]

Morphology

[edit]Ottawa has complex systems of both inflectional and derivational morphology. Inflectional morphology has a central role in Ottawa grammar. Noun inflection and verb inflection indicate grammatical information through prefixes and suffixes that are added to word stems.[85]

Notable grammatical characteristics marked with inflectional prefixes and suffixes include:

- A distinction between obviative and proximate third person, marked on both verbs and nouns.[86]

- Extensive marking on verbs of inflectional information concerning person.[87]

- Number (singular and plural).[88]

- Tense.[89]

- Modality.[90]

- Evidentiality.[91]

- Negation.[92]

Prefixes mark grammatical person on verbs, including first person, second person, and third person.[93] Nouns use combinations of prefixes and suffixes to indicate possession. Suffixes on nouns mark gender,[94] location,[95] diminutive,[96] pejorative,[97] and other categories.[98] Significant agreement patterns between nouns and verbs involve gender, singular and plural number, as well as obviation.[99]

Ottawa derivational morphology forms basic word stems with combinations of word roots (also called initials), and affixes referred to as medials and finals to create words to which inflectional prefixes and suffixes are added.[100] Word stems are combined with other word stems to create compound words.[101]

Innovations in Ottawa morphology contribute to differentiating Ottawa from other dialects of Ojibwe. These differences include: the reanalysis of person prefixes and word stems;[58] the loss of final /-n/ in certain inflectional suffixes;[102] a distinctive form for the verbal suffix indicating doubt;[103] and a distinctive form for the verbal suffix indicating plurality on intransitive verbs with grammatically inanimate subjects.[104]

The most significant of the morphological innovations that characterize Ottawa is the restructuring of the three person prefixes that occur on both nouns and verbs. The prefixes carry grammatical information about grammatical person (first, second, or third). Syncope modifies the pronunciation of the prefixes by deleting the short vowel in each prefix.[105]

| English | Non-Syncopating Dialects | Ottawa |

|---|---|---|

| (a) first-person prefix | ni- | n- |

| (b) second person prefix | gi- | g- |

| (c) third-person | o- | — (no form) |

The third-person prefix /o-/, which occurs with both nouns and verbs, is completely eliminated in Ottawa.[106] As a result, there is no grammatical marker to indicate third-person on inflected forms of nouns or verbs. For example, where other dialects have jiimaan 'a canoe' with no person prefix, and ojimaan 'his/her canoe' with prefix o-, Ottawa has jiimaan meaning either 'canoe' or 'his/her canoe' (with no prefix, because of syncope).[107] Apart from the simple deletion of vowels in the prefixes, Ottawa has created new variants for each prefix.[108] Restructuring of the person prefixes is discussed in detail in Ottawa morphology.

Syntax

[edit]Syntax refers to patterns for combining words and phrases to make clauses and sentences.[109] Verbal and nominal inflectional morphology are central to Ottawa syntax, as they mark grammatical information on verbs and nouns to a greater extent than in English (which has few inflections, and relies mainly on word order).[110] Preferred word orders in a simple transitive sentence are verb-initial, such as verb–object–subject (VOS) and VSO. While verb-final orders are avoided, all logically possible orders are attested.[111] Ottawa word order displays considerably more freedom than is found in languages such as English, and word order frequently reflects discourse-based distinctions such as topic and focus.[112]

Verbs are marked for grammatical information in three distinct sets of inflectional paradigms, called Verb orders. Each order corresponds generally to one of three main sentence types: the Independent order is used in main clauses, the Conjunct order in subordinate clauses, and the Imperative order in commands.[113]

Ottawa distinguishes yes–no questions, which use a verb form in the Independent order, from content questions formed with the Ottawa equivalents of what, where, when, who and others, which require verbs inflected in the Conjunct order.[114]

Ottawa distinguishes two types of grammatical third person in sentences, marked on both verbs and animate nouns. The proximate form indicates a more salient noun phrase, and obviative indicates a less prominent noun phrase. Selection and use of proximate or obviative forms is a distinctive aspect of Ottawa syntax that indicates the relative discourse prominence of noun phrases containing third persons; it does not have a direct analogue in English grammar.[86]

Vocabulary

[edit]Few vocabulary items are considered unique to Ottawa.[104] The influx of speakers of other Ojibwe dialects into the Ottawa area has resulted in mixing of historically distinct dialects. Given that vocabulary spreads readily from one dialect to another, the presence of a particular vocabulary item in a given dialect is not a guarantee of the item's original source.[115] Two groups of function words are characteristically Ottawa: the sets of demonstrative pronouns and interrogative adverbs are both distinctive relative to other dialects of Ojibwe. Although some of the vocabulary items in each set are found in other dialects, taken as a group each is uniquely Ottawa.[116]

Demonstrative pronouns

[edit]Ottawa uses a set of demonstrative pronouns that contains terms unique to Ottawa, while other words in the set are shared with other Ojibwe dialects. Taken as a group the Ottawa set is distinctive.[117] The following chart shows the demonstrative pronouns for: (a) Wikwemikong, an Ottawa community; (b) Curve Lake, an Eastern Ojibwe community; and (c) Cape Croker, an Ottawa community that uses a mixed pronoun set. The terms maaba 'this (animate)', gonda 'these (animate)', and nonda 'these (inanimate)' are unique to Ottawa.[118]

| English | Wikwemikong | Curve Lake | Cape Croker |

|---|---|---|---|

| this (inanimate) | maanda | ow | maanda |

| that (inanimate) | iw, wi | iw | iw |

| these (inanimate) | nonda | now | now |

| those (inanimate) | niw | niw | niw |

| this (animate) | maaba | aw | maaba |

| that (animate) | aw, wa | aw | aw |

| these (animate) | gonda | gow | gow |

| those (animate) | giw | giw | giw |

Interrogative pronouns and adverbs

[edit]Ottawa interrogative pronouns and adverbs frequently have the emphatic pronoun dash fused with them to form a single word. In this table the emphatic pronoun is written as -sh immediately following the main word.[73]

| English | Ottawa | Eastern Ojibwe |

|---|---|---|

| which | aanii-sh, aanii | aaniin |

| where | aanpii-sh, aapii, aapii-sh | aandi |

| who | wene-sh, wenen | wenen |

| how | aanii-sh, aanii | aaniin |

Other vocabulary

[edit]A small number of vocabulary items are characteristically Ottawa.[119] Although these items are robustly attested in Ottawa, they have also been reported in some other communities.[120]

| English | Ottawa Terms | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| come here! | maajaan | — |

| father, my | noos | Also Border Lakes Ojibwe, Eastern Ojibwe, Saulteaux |

| mother, my | ngashi | — |

| pants | miiknod | Also Algonquin |

| long ago | zhaazhi | — |

| necessarily | aabdig | Also Eastern Ojibwe |

| be small (animate verb) | gaachiinyi | — |

Writing system

[edit]

Written representation of Ojibwe dialects, including Ottawa, was introduced by European explorers, missionaries and traders who were speakers of English and French. They wrote Ottawa words and sentences using their own languages' letters and orthographic conventions, adapting them to the unfamiliar new language.[123][124] Indigenous writing in Ottawa was also based upon English or French, but only occurred sporadically through the 19th and 20th centuries.[125][126][127] Modern focus on literacy and use of written forms of the language has increased in the context of second-language learning, where mastery of written language is viewed as a component of the language-learning process.[128] Although there has never been a generally accepted standard written form of Ottawa, interest in standardization has increased with the publication of a widely used dictionary in 1985 and reference grammar in 2001, which provide models for spelling conventions.[129][21] A conference held in 1996 brought together speakers of all dialects of Ojibwe to review existing writing systems and make proposals for standardization.[130]

Early orthographic practices

[edit]19th-century missionary authors who wrote in Ottawa include Catholic missionary Frederic Baraga and Anglican Frederick O'Meara (illustration, this section).[121][131][132] Ottawa speaker Andrew Blackbird wrote a history of his people in English; an appended grammatical description of Ottawa and the Southwestern Ojibwe (Chippewa) dialect also contains vocabulary lists, short phrases, and translations of the Ten Commandments and the Lord's Prayer.[133] Accurate transcriptions of Ottawa date from linguist Leonard Bloomfield's research with Ottawa speakers in the late 1930s and early 1940s.[134][135]

A tradition of indigenous literacy in Ottawa arose in the 19th century, as speakers of Ottawa on Manitoulin Island became literate in their own language.[136] Manitoulin Island Ottawas who were Catholic learned to write from French Catholic missionaries using a French-influenced orthography,[137] while Methodist and Anglican converts used English-based orthographies.[138] Documents written in Ottawa by Ottawa speakers on Manitoulin Island between 1823 and 1910 include official letters and petitions, personal documents, official Indian band regulations, an official proclamation, and census statements prepared by individuals.[139] Ottawa speakers from Manitoulin Island contributed articles to Anishinabe Enamiad ('the Praying Indian'), an Ojibwe newspaper started by Franciscan missionaries and published in Harbor Springs, Michigan between 1896 and 1902.[136]

It has been suggested that Ottawa speakers were among the groups that used the Great Lakes Algonquian syllabary, a syllabic writing system derived from a European-based alphabetic orthography,[140] but supporting evidence is weak.[141]

Modern orthography

[edit]Although there is no standard or official writing system for Ottawa, a widely accepted system is used in a recent dictionary of Ottawa and Eastern Ojibwe,[129] a collection of texts,[142] and a descriptive grammar.[21] The same system is taught in programs for Ojibwe language teachers.[143][144] One of its goals is to promote standardization of Ottawa writing so that language learners are able to read and write in a consistent way. By comparison, folk phonetic spelling approaches to writing Ottawa based on less systematic adaptations of written English or French are more variable and idiosyncratic, and do not always make consistent use of alphabetic letters.[128] While the modern orthography is used in a number of prominent publications, its acceptance is not universal. Prominent Ottawa author Basil Johnston has explicitly rejected it, preferring to use a form of folk spelling in which the correspondences between sounds and letters are less systematic.[145][146] Similarly, a lexicon representing Ottawa as spoken in Michigan and another based on Ottawa in Oklahoma, use English-based folk spellings distinct from that employed by Johnson.[38][147]

The Ottawa writing system is a minor adaptation of a very similar one used for other dialects of Ojibwe in Ontario and the United States, and widely employed in reference materials and text collections.[148][149] Sometimes referred to as the Double Vowel system[144] because it uses doubled vowel symbols to represent Ottawa long vowels that are paired with corresponding short vowels, it is an adaptation attributed to Charles Fiero[128] of the linguistically oriented system found in publications such as Leonard Bloomfield's Eastern Ojibwa.[134] Letters of the English alphabet substitute for specialized phonetic symbols, in conjunction with orthographic conventions unique to Ottawa. The system embodies two basic principles: (1) alphabetic letters from the English alphabet are used to write Ottawa, but with Ottawa sound values; (2) the system is phonemic in nature, in that each letter or letter combination indicates its basic sound value, and does not reflect all the phonetic detail that occurs. Accurate pronunciation cannot be learned without consulting a fluent speaker.[150]

The Ottawa variant of this system uses the following consonant letters or digraphs:

b, ch, d, f, g, h, j, k, l, m, n, p, r, s, sh, t, w, y, z, zh

The letters f, l, and r are found in loan words, such as telephonewayshin 'give me a call' and refrigeratoring 'in the refrigerator'.[151] Loan words that have recently been borrowed from English are typically written in standard English orthography.[152]

The letter h is used for the glottal stop [ʔ], which is represented in the broader Ojibwe version with the apostrophe. In Ottawa the apostrophe is reserved for a separate function noted below.[148] In a few primarily expressive words, orthographic h has the phonetic value [h]: aa haaw 'OK'.[153]

Vowels are represented as follows:

Long ii, oo, aa, e; Short i, o, a

By convention the three long vowels that correspond to a short vowel are written double, while the single long vowel written as orthographic e that does not have a corresponding short vowel is not written doubled.[154]

The apostrophe ’ is used to distinguish primary (underlying) consonant clusters from secondary clusters that arise when the rule of syncope deletes a vowel between two consonants. For example, orthographic ng must be distinguished from n'g. The former has the phonetic value [ŋ] (arising from place of articulation assimilation of /n/ to the following velar consonant /ɡ/, which is then deleted in word-final position as in mnising [mnɪsɪŋ] 'at the island'), while the latter has the phonetic value [nɡ] as in san'goo [sanɡoː] 'black squirrel'.[155]

History

[edit]In the general model of linguistic change, "a single ancestor language (a proto-language) develops dialects which in time through the accumulation of changes become distinct languages."[156] Continued changes in the descendant languages result in the development of dialects which again over time develop into distinct languages.[156] The Ojibwe language is a historical descendant of Proto-Algonquian, the reconstructed ancestor language of the Algonquian languages. Ojibwe has subsequently developed a series of dialects including Ottawa, which is one of the three dialects of Ojibwe that has innovated the most through its historical development, along with Severn Ojibwe and Algonquin.[17]

History of scholarship

[edit]Explorer Samuel de Champlain was the first European to record an encounter with Ottawa speakers when he met a party of three hundred Ottawas in 1615 on the north shore of Georgian Bay.[157] French missionaries, particularly members of the Society of Jesus and the Récollets order, documented several dialects of Ojibwe in the 17th and 18th centuries, including unpublished manuscript Ottawa grammatical notes, word lists, and a dictionary.[158][159]

In the 19th century, Ottawa speaker Andrew Blackbird wrote a history of the Ottawa people that included a description of Ottawa grammatical features.[133] The first linguistically accurate work was Bloomfield's description of Ottawa as spoken at Walpole Island, Ontario.[134] The Odawa Language Project at the University of Toronto, led by Kaye and Piggott, conducted field work in Ottawa communities on Manitoulin Island in the late 1960s and early 1970s, resulting in a series of reports on Ottawa linguistics.[160][161] Piggott also prepared a comprehensive description of Ottawa phonology.[162] Rhodes produced a study of Ottawa syntax,[163] a dictionary,[129] and a series of articles on Ottawa grammar.[164] Valentine has published a comprehensive descriptive grammar,[21] a volume of texts including detailed analysis,[142] as well as a survey of Ojibwe dialects that includes extensive description and analysis of Ottawa dialect features.[16]

There has been one major anthropological/linguistic study of the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians. Jane Willetts Ettawageshik devoted approximately two years of study in the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians community. Jane Willetts Ettawageshik recorded Anishinaabe stories speak of how the Anishinaabe people related to their land, to their people, and various other means of communicating their values, outlooks and histories in and around Northern Michigan. These stories have been translated into a book, Ottawa Stories from the Springs, Anishinaabe dibaadjimowinan wodi gaa binjibaamigak wodi mookodjiwong e zhinikaadek,[165] by Howard Webkamigad.

Sample text

[edit]Traditional Ottawa stories fall into two general categories, aadsookaan 'legend, sacred story'[166] and dbaajmowin 'narrative, story'.[167] Stories in the aasookaan category involve mythical beings such as the trickster character Nenbozh.[168][169] Stories in the dbaajmowin category include traditional stories that do not necessarily involve mythical characters,[170] although the term is also used more generally to refer to any story not in the aasookaan category. Published Ottawa texts include a range of genres, including historical narratives,[171] stories of conflict with other indigenous groups,[172] humorous stories,[173] and others.[169][174]

Ottawa speaker Andrew Medler dictated the following text while working with linguist Leonard Bloomfield in a linguistic field methods class at the 1939 Linguistic Society of America Summer Institute.[175] Medler grew up near Saginaw, Michigan but spent most of his life at Walpole Island.[176] The texts that Medler dictated were originally published in a linguistically oriented transcription using phonetic symbols,[134] and have been republished in a revised edition that uses the modern orthography and includes detailed linguistic analyses of each text.[177]

Love Medicine

Andrew Medler

(1) Ngoding kiwenziinh ngii-noondwaaba a-dbaajmod wshkiniigkwen gii-ndodmaagod iw wiikwebjigan.

- 'Once I heard an old man tell of how a young woman asked him for love medicine.'

(2) Wgii-msawenmaan niw wshkinwen.

- 'She was in love with a young man.'

(3) Mii dash niw kiwenziinyan gii-ndodmawaad iw wiikwebjigan, gye go wgii-dbahmawaan.

- 'So then she asked that old man for the love medicine, and she paid him for it.'

(4) Mii dash gii-aabjitood maaba wshkiniigkwe iw mshkiki gaa-giishpnadood.

- 'Then this young woman used that medicine that she had bought.'

(5) Mii dash maaba wshkinwe gaa-zhi-gchi-zaaghaad niw wshkiniigkwen.

- 'Then this young man accordingly very much loved that young woman.'

(6) Gye go mii gii-wiidgemaad, gye go mii wiiba gii-yaawaawaad binoojiinyan.

- 'Then he married her; very soon they had children.'

(7) Aapji go gii-zaaghidwag gye go gii-maajiishkaawag.

- 'They loved each other and they fared very well.'

Additionally, there has been a book release titled Ottawa Stories from the Springs, Anishinaabe dibaadjimowinan wodi gaa binjibaamigak wodi mookodjiwong e zhinikaadek[165] by Howard Webkamigad. This book translates recordings from the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa that were recorded by Jane Willetts Ettawageshik between 1946–1949. It contains over 25 stories of various sorts including many stories of the two general categories, aadsookaan 'legend, sacred story'[166] and dbaajmowin 'narrative, story'.[167]

This book is historically significant as the recordings by Jane Willetts Ettawageshik were the first recordings of the Odawa dialect in Northern Michigan and have not been previously translated prior to the books published by Howard Wabkamigad. The original recordings are archived at the American Philosophical Society.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Ottawa dialect at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ^ "Detailed Languages Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and Over: 2017-2021". Census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 6 June 2025.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2022-08-17). "Knowledge of languages by age and gender: Canada, provinces and territories, census divisions and census subdivisions". www150.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2022-12-24.

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 1994, p. 17

- ^ Nichols, John and Earl Nyholm, 1995, p. 10

- ^ Baraga, Frederic, 1878, p. 336 gives ⟨Otawamowin⟩.

- ^ Rayburn, Alan, 1997, p. 259

- ^ See Bright, William, 2004, p. 360 for other uses of "Ottawa" as a place name.

- ^ Feest, Johanna and Christian Feest, 1978, p. 785

- ^ Goddard, Ives, 1979, p. 95

- ^ Hock, Hans, 1991, p. 381

- ^ Mithun, Marian, 1999, p. 298

- ^ Campbell, Lyle, 2004, p. 217

- ^ a b Mithun, Marian, 1999, pp. 298–299

- ^ Hockett, Charles F., 1958, pp. 323–326 develops a model of language complexes; he uses the term "L-complex"

- ^ a b c Valentine, J. Randolph, 1994

- ^ a b Valentine, J. Randolph, 1994, pp. 43–44

- ^ a b Rhodes, Richard and Evelyn Todd, 1981, p. 52

- ^ As in e.g. Wolfart, H. Christoph, 1989, p. 1

- ^ Significant publications include Bloomfield, Leonard, 1958; Piggott, Glyne, 1980; Rhodes, Richard, 1985; Valentine, J. Randolph, 1994; Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001

- ^ a b c d Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001

- ^ Rhodes, Richard, 1985, p. x

- ^ Linguistic and cultural affiliations of Canada Indian bands, 1980, p. 20

- ^ a b c d e Linguistic and cultural affiliations of Canada Indian bands, 1980, p. 24

- ^ a b Linguistic and cultural affiliations of Canada Indian bands, 1980, p. 21

- ^ Mississauga (Mississagi River 8 Reserve) Aboriginal Canada Portal: Aboriginal Communities: First Nations, Inuit and Métis. Retrieved on March 27, 2009.

- ^ a b c Linguistic and cultural affiliations of Canada Indian bands, 1980, p. 23

- ^ Serpent River First Nation Archived 2008-05-10 at the Wayback Machine. Aboriginal Canada Portal: Aboriginal Communities: First Nations, Inuit and Métis. Retrieved on March 27, 2009.

- ^ Whitefish River First Nation Whitefish River Community Web Site. Retrieved on March 27, 2009.

- ^ Linguistic and cultural affiliations of Canada Indian bands, 1980, p. 19

- ^ Sheshegwaning First Nation. Sheshegwaning First Nation Community web site. Retrieved on March 27, 2009.

- ^ Sucker Creek First Nation. Aboriginal Canada Portal: Aboriginal Communities: First Nations, Inuit and Métis. Retrieved on March 27, 2009.

- ^ Sheguiandah First Nation. Aboriginal Canada Portal: Aboriginal Communities: First Nations, Inuit and Métis. Retrieved on March 27, 2009.

- ^ a b Rhodes, Richard and Evelyn Todd, 1981, p. 54, Fig. 2

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, p. 2

- ^ a b Rhodes, Richard, 1985, pp. x–xi

- ^ Feest, Johanna and Christian Feest, 1978, p. 779, Fig. 6

- ^ a b Dawes, Charles, 1982

- ^ Status of Indian languages in Oklahoma. Status of Indian Languages in Oklahoma. Archived 2010-09-17 at the Wayback Machine Intertribal Wordpath Society. Norman, Oklahoma. Retrieved April 6, 2009.

- ^ Various Languages Spoken (147), Age Groups (17A) and Sex (3) for the Population of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2006 Census - 20% Sample Data Archived 2018-12-25 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on March 31, 2009.

- ^ Gordon, Raymond, 2005. See online version of same: Ethnologue entry for Ottawa. Retrieved September 14, 2009

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 1998, p. 2

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, p. 1

- ^ a b Feest, Johanna and Christian Feest, 1978, p. 772

- ^ Rogers, Edward, 1978, pp. 760, 764, 764, Fig. 3

- ^ Clifton, James, 1978, p. 739

- ^ Rhodes, Richard, 1985 p. xi

- ^ a b Rhodes, Richard, 1982, p. 4

- ^ Rhodes, Richard, 1985, p. li

- ^ a b Rhodes, Richard, 1985, pp. xxxix–xliii

- ^ Rhodes, Richard, 1976a, p. 135

- ^ See e.g. Nichols, John, and Earl Nyholm, 1995, for the segmental inventories of Southwestern Ojibwe, and Todd, Evelyn, 1970 for Severn Ojibwe

- ^ See Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 29–32 for a discussion of the relationship between sounds and orthography

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 51–67

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 52–54, 57–59

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 76–83

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 73–74

- ^ a b Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 59–67

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 66–67, 71

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, p. 50

- ^ Rhodes, Richard, 1985, pp. xlv, xlvii, liii

- ^ Nichols, John and Earl Nyholm, 1995, p. xxxvi

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 48–49

- ^ Rhodes, Richard, 1985, pp. xlix–l, l–li, xlvii,

- ^ Rhodes, Richard, 1985, p. xlvii

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 74–81

- ^ Rhodes, Richard, 1985, pp. xvlvi, xlvii

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 34–41

- ^ Rhodes, Richard, 1985, p. xlii

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, p. 54

- ^ Rhodes, Richard, 1985, pp. xxxix-xlii

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 185–188

- ^ a b Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, p. 19

- ^ a b c Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, p. 40

- ^ Bloomfield, Leonard, 1958, p. 7

- ^ Piggott, Glyne, 1980, pp. 110-111; Piggott's transcription of words containing long nasal vowels differs from those of Rhodes, Bloomfield, and Valentine by allowing for an optional [ʔ] after the long nasal vowel in phonetic forms.

- ^ Nichols, John, 1980, p. 6

- ^ Rhodes, Richard, 1985, p. xxiv

- ^ Blackbird, Andrew J., 1887, p. 120

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, Ch. 3

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, p. 113

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 114–121, 130–135

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 114–121

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, p. 116

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 104–105

- ^ a b Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 623–643

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, Chapters 5–8; pp. 62–72

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, p. 178

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 759–782

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, p. 759

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 830–837

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 837–856

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 62–72

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 177–178

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 743–748

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 185–190

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 190–193

- ^ See Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, Ch. 5 for an extensive survey.

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, Chs. 4–8

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 318–335

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 335, 515–522

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 18–19

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 1994, pp. 427–428

- ^ a b Valentine, J. Randolph, 1994, p. 430

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 63–64

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, p. 64

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 64–67, 82–83

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 1994, pp. 143–147

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, p. 916

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, p. 918

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 934–935

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 951–955

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 991–996

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, pp. 975–991

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 1994, pp. 430–431

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 1994, pp. 424, 428

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, p. 18

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 1994, p. 424

- ^ Rhodes, Richard, 1976a, pp. 150-151

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 1994, pp. 430–434; other items listed, p. 431

- ^ a b O'Meara, Frederick, 1854

- ^ Pilling, James, 1891, p. 381

- ^ Hanzeli, Victor, 1961; see especially Chs. 5 and 6

- ^ Goddard, Ives, 1996b, pp. 17, 20

- ^ Pentland, David, 1996, pp. 261–262

- ^ For general discussion see Walker, Willard, 1996, pp. 158, 173–176

- ^ Rhodes, Richard and Evelyn Todd, 1981, pp. 62–65

- ^ a b c Nichols, John and Lena White, 1987, p. iii

- ^ a b c Rhodes, Richard, 1985

- ^ Ningewance, Patricia, 1999

- ^ Baraga, Frederic, 1832

- ^ O'Meara, Frederick, 1844

- ^ a b Blackbird, Andrew J., 1887, pp. 107-128

- ^ a b c d Bloomfield, Leonard, 1958

- ^ Nichols, John and Leonard Bloomfield, 1991

- ^ a b Corbiere, Alan, 2003

- ^ Pentland, David, 1996, p. 267

- ^ Corbiere, Alan, 2003, p. 58

- ^ Corbiere, Alan, 2003, pp. 58, 65, 68, 70

- ^ Walker, Willard, 1996, pp. 168-169

- ^ Goddard, Ives, 1996, pp. 126–127

- ^ a b Valentine, J. Randolph, 1998

- ^ Native Language Instructors' Program. Native Language Instructors' Program, Lakehead University Faculty of Education, Lakehead University. Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada. Retrieved on March 27, 2009.

- ^ a b Ningewance, Patricia, 1999, p. 2

- ^ Johnston, Basil, 2007, pp. vii-viii

- ^ Johnston, Basil, 1979

- ^ Cappell, Constance, 2006, pp. 157-196, 232

- ^ a b Nichols, John and Earl Nyholm, 1995

- ^ Kegg, Maude, 1991

- ^ Nichols, John and Earl Nyholm, 1995, p. xxiii

- ^ Rhodes, Richard, 1985, pp. xxxi, xxxv

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, p. 90

- ^ Rhodes, Richard, 1985, xlvi

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 2001, p. 34

- ^ Rhodes, Richard, 1985, p. xlix

- ^ a b Campbell, Lyle, 2004, pp. 211–212

- ^ Fox, William, 1990, p. 457

- ^ Hanzeli, Victor, 1961, pp. 237-238

- ^ See Hanzeli, Victor, 1969, pp. 122-124 for the text and a facsimile reproduction from two pages of a circa 1688 manuscript of Ottawa grammatical notes and vocabulary attributed to Louis André, a Jesuit.

- ^ Kaye, Jonathan, Glyne Piggott and Kensuke Tokaichi, eds., 1971

- ^ Piggott, Glyne and Jonathan Kaye, eds, 1973

- ^ Piggott, Glyne, 1980

- ^ Rhodes, Richard, 1976

- ^ See Further Reading for articles by Rhodes on Ottawa grammar.

- ^ a b "Ottawa Stories from the Springs". Michigan State University. 13 August 2019. Retrieved 2022-04-10.

- ^ a b Rhodes, Richard, 1985, p. 14

- ^ a b Rhodes, Richard, 1985, p. 103

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 1988, pp. 197–215, 113–115; Piggott, Glyne, 1985, pp. 11–16; Piggott, Glyne, 1985a, pp. 13–16

- ^ a b Nichols, John and Leonard Bloomfield, 1991, pp. 18–23

- ^ Piggott, Glyne, 1985a, pp. 1–12

- ^ Piggott, Glyne, 1985, pp. 1–10

- ^ McGregor, Gregor with C. F. Voegelin, 1988, pp. 114–118

- ^ Fox, Francis and Nora Soney with Richard Rhodes, 1988

- ^ Wilder, Julie, ed., 1999

- ^ Bloomfield, Leonard, 1958, p. vii

- ^ Bloomfield, Leonard, 1958, p. viii

- ^ Valentine, J. Randolph, 1998, pp. 57, 167, 239–240

References

[edit]- Baraga, Frederic. 1832. Otawa anamie-misinaigan. Detroit: George L. Whitney.

- Baraga, Frederic. 1878. A Dictionary of the Otchipwe Language, Explained in English. A New edition, by a missionary of the Oblates. Part I, English-Otchipwe; Part II, Otchipwe-English. Montréal: Beauchemin & Valois. Reprint (in one volume), Minneapolis: Ross and Haines, 1966, 1973.

- Blackbird, Andrew J. 1887. History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan: A grammar of their language, and personal and family history of the author. Retrieved April 10, 2009. Ypsilanti, MI: The Ypsilantian Job Printing House. (Reprinted as: Complete both early and late history of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan [etc.]. Harbor Springs, MI. Babcock and Darling.)

- Bloomfield, Leonard. 1958. Eastern Ojibwa: Grammatical sketch, texts and word list. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Bright, William, 2004. Native American Place Names of the United States. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3598-4

- Campbell, Lyle. 2004. Historical linguistics: An introduction. Second edition. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-53267-9

- Cappel, Constance, ed. 2006. Odawa Language and Legends: Andrew J. Blackbird and Raymond Kiogima. Philadelphia: Xlibris[self-published source]. ISBN 978-1-59926-920-7

- Clifton, James. 1978. "Potawatomi." Bruce Trigger, ed., The Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 15. Northeast, pp. 725–742. Washington, D.C.: The Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-004575-4

- Corbiere, Alan. 2003. "Exploring historical literacy in Manitoulin Island Ojibwe." H.C. Wolfart, ed., Papers of the thirty-fourth Algonquian conference, pp. 57–80. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba. ISSN 0831-5671

- Dawes, Charles E. 1982. Dictionary English-Ottawa Ottawa-English. No publisher given.

- Feest, Johanna, and Christian Feest. 1978. "Ottawa." Bruce Trigger, ed., The Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 15. Northeast, pp. 772–786. Washington, D.C.: The Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-004575-4

- Fox, William A. 1990. "The Odawa." Chris J. Ellis and Neal Ferris, eds., The archaeology of Southern Ontario to A.D. 1650, pp. 457–473. Occasional Publications of the London Chapter, Ontario Archaeological Society Inc., Publication Number 5. ISBN 0-919350-13-5

- Fox, Francis and Nora Soney with Richard Rhodes. 1988. "Chippewa-Ottawa texts." John Nichols, ed., An Ojibwe text anthology, pp. 33–68. London: The Centre for Teaching and Research of Canadian Native Languages, University of Western Ontario. ISBN 0-7714-1046-8

- Goddard, Ives. 1979. "Comparative Algonquian." Lyle Campbell and Marianne Mithun, eds, The languages of Native America, pp. 70–132. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-74624-5

- Goddard, Ives. 1994. "The West-to-East Cline in Algonquian Dialectology." William Cowan, ed., Papers of the 25th Algonquian Conference, pp. 187–211. Ottawa: Carleton University. ISSN 0831-5671

- Goddard, Ives. 1996. "Writing and reading Mesquakie (Fox)." W. Cowan, ed., Papers of the twenty-seventh Algonquian conference, pp. 117–134. Ottawa: Carleton University. ISSN 0831-5671

- Goddard, Ives. 1996a. "Introduction." Ives Goddard, ed., The Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 17. Languages, pp. 1–16. Washington, D.C.: The Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-048774-9

- Goddard, Ives. 1996b. "The description of the native languages of North America before Boas." Ives Goddard, ed., The Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 17. Languages, pp. 17–42. Washington, D.C.: The Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-048774-9

- Hanzeli, Victor. 1961. Early descriptions by French missionaries of Algonquian and Iroquoian languages: A study of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century practice in linguistics. PhD dissertation. Indiana University. Bloomington.

- Hanzeli, Victor. 1969. Missionary linguistics in New France: A study of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century descriptions of American Indian languages. The Hague: Mouton.

- Hock, Hans Heinrich. 1991. Principles of historical linguistics. Second edition. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-012962-0

- Hockett, Charles F. 1958. A course in modern linguistics. New York: MacMillan.

- Intertribal Wordpath Society. Status of Indian Languages in Oklahoma. Intertribal Wordpath Society. Norman, OK. Retrieved April 6, 2009.

- Johnston, Basil. 1979. Ojibway language lexicon for beginners. Ottawa: Education and Cultural Support Branch, Indian and Northern Affairs.

- Johnston, Basil. 2007. Anishinaube Thesaurus. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87013-753-2

- Kaye, Jonathan, Glyne Piggott and Kensuke Tokaichi, eds. 1971. Odawa language project. First Report. Toronto: University of Toronto Anthropology Series 9.

- Kegg, Maude. 1991. Edited and transcribed by John D. Nichols. Portage Lake: Memories of an Ojibwe Childhood. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press. ISBN 0-8166-2415-1

- Linguistic and cultural affiliations of Canada Indian bands. 1980. Indian and Inuit Affairs Program. Research Branch: Corporate Policy. Ottawa: Indian and Northern Affairs Canada.

- McGregor, Gregor with C. F. Voegelin. 1988. "Birch Island Texts." Edited by Leonard Bloomfield and John D. Nichols. John Nichols, ed., An Ojibwe text anthology, pp. 107–194. London: The Centre for Teaching and Research of Canadian Native Languages, University of Western Ontario. ISBN 0-7714-1046-8

- Mississauga (Mississagi River 8 Reserve) Aboriginal Canada Portal: Aboriginal Communities: First Nations, Inuit and Métis. Retrieved on March 27, 2009.

- Mithun, Marianne. 1999. The Languages of Native North America. Cambridge: University Press. ISBN 0-521-23228-7

- Native Language Instructors' Program. Native Language Instructors' Program, Lakehead University Faculty of Education, Lakehead University. Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada. Retrieved on March 27, 2009.

- Nichols, John. 1980. Ojibwe morphology. PhD dissertation, Harvard University.

- Nichols, John D. and Leonard Bloomfield, eds. 1991. The dog's children. Anishinaabe texts told by Angeline Williams. Winnipeg: Publications of the Algonquian Text Society, University of Manitoba. ISBN 0-88755-148-3

- Nichols, John and Earl Nyholm. 1995. A concise dictionary of Minnesota Ojibwe. St. Paul: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-2427-5

- Nichols, John and Lena White. 1987. Nishnaabebii'gedaa: Exercises in writing for speakers of Central Ojibwa and Odawa. University of Manitoba: Readers and Studies Guides, Department of Native Studies. ISSN 0711-382X

- Ningewance, Patricia. 1999. Naasaab izhi-anishinaabebii'igeng: Conference report. A conference to find a common Anishinaabemowin writing system. Toronto: Queen's Printer for Ontario. ISBN 0-7778-8695-2

- O'Meara, Frederick. 1844. Kaezhetabwayandungebun kuhya kaezhewaberepun owh anuhmeaud keahneshnahbabeèegahdag keahnekenootahtahbeung. Retrieved April 10, 2009. Cobourgh [Ont.] : Printed at the Diocesan Press for the Church Society of the Diocese of Toronto, 1844.

- O'Meara, Frederick. 1854. Ewh oowahweendahmahgawin owh tabanemenung Jesus Christ: keahnekuhnootuhbeegahdag anwamand egewh ahneshenahbag Ojibway anindjig: keenahkoonegawaud kuhya ketebahahmahgawaud egewh mahyahmahwejegajig Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge ewede London anduhzhetahwaud. [New Testament in Ojibwe] Retrieved April 10, 2009. Toronto: H. Rowsell.

- Pentland, David. 1996. "An Ottawa letter to the Algonquin chiefs at Oka." Brown, Jennifer and Elizabeth Vibert, eds., Reading beyond words: Contexts for Native history, pp. 261–279. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press. ISBN 1-55111-070-9

- Piggott, Glyne L. 1980. Aspects of Odawa morphophonemics. New York: Garland. (Published version of PhD dissertation, University of Toronto, 1974) ISBN 0-8240-4557-2

- Piggott, Glyne L., ed. 1985. Three stories from the Odawa language project. Algonquian and Iroquoian Linguistics, Readers and Study Guides. Winnipeg: Department of Native Studies, University of Manitoba. ISSN 0711-382X

- Piggott, Glyne L., ed. 1985a. Stories of Sam Osawamick from the Odawa language project. Algonquian and Iroquoian Linguistics, Readers and Study Guides. Winnipeg: Department of Native Studies, University of Manitoba. ISSN 0711-382X

- Piggott, Glyne and Jonathan Kaye, eds. 1973. Odawa language project. Second report. Toronto: University of Toronto Linguistics Series 1.

- Pilling, James Constantine. 1891. Bibliography of the Algonquian languages. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 13. Washington: Government Printing Office.

- Rayburn, Alan. 1997. Place names of Ontario. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-0602-7

- Rhodes, Richard. 1976. The morphosyntax of the Central Ojibwa verb. PhD dissertation, University of Michigan.

- Rhodes, Richard. 1976a. "A preliminary report on the dialects of Eastern Ojibwa–Odawa." W. Cowan, ed., Papers of the seventh Algonquian conference, pp. 129–156. Ottawa: Carleton University.

- Rhodes, Richard. 1982. "Algonquian trade languages." William Cowan, ed., Papers of the thirteenth Algonquian conference, pp. 1–10. Ottawa: Carleton University. ISBN 0-7709-0123-9

- Rhodes, Richard A. 1985. Eastern Ojibwa-Chippewa-Ottawa Dictionary. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-013749-6

- Rhodes, Richard and Evelyn Todd. 1981. "Subarctic Algonquian languages." June Helm, ed., The Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 6. Subarctic, pp. 52–66. Washington, D.C.: The Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-004578-9

- Ritzenthaler, Robert. 1978. "Southwestern Chippewa." Bruce Trigger, ed., The Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 15. Northeast, pp. 743–759. Washington, D.C.: The Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-004575-4

- Rogers, Edward. 1978. "Southeastern Ojibwa." Bruce Trigger, ed., The Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 15. Northeast, pp. 760–771. Washington, D.C.: The Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-004575-4

- Serpent River First Nation Aboriginal Canada Portal: Aboriginal Communities: First Nations, Inuit and Métis. Retrieved on March 27, 2009.

- Sheguiandah First Nation Aboriginal Canada Portal: Aboriginal Communities: First Nations, Inuit and Métis. Retrieved on March 27, 2009.

- Sheshegwaning First Nation Community web site. Retrieved on March 27, 2009.

- Sucker Creek First Nation Aboriginal Canada Portal: Aboriginal Communities: First Nations, Inuit and Métis. Retrieved on March 27, 2009.

- Todd, Evelyn. 1970. A grammar of the Ojibwa language: The Severn dialect. PhD dissertation, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

- Valentine, J. Randolph. 1994. Ojibwe dialect relationships. PhD dissertation, University of Texas, Austin.

- Valentine, J. Randolph. 1998. Weshki-bimaadzijig ji-noondmowaad. 'That the young might hear': The stories of Andrew Medler as recorded by Leonard Bloomfield. London, ON: The Centre for Teaching and Research of Canadian Native Languages, University of Western Ontario. ISBN 0-7714-2091-9

- Valentine, J. Randolph. 2001. Nishnaabemwin Reference Grammar. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-4870-6

- Various Languages Spoken (147), Age Groups (17A) and Sex (3) for the Population of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2006 Census - 20% Sample Data Archived 2018-12-25 at the Wayback Machine. 2006. Statistics Canada. Retrieved on March 31, 2009.

- Walker, Willard. 1996. "Native writing systems." Ives Goddard, ed., The Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 17. Languages, pp. 158–184. Washington, D.C.: The Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-048774-9

- Whitefish River First Nation Community Web Site. Retrieved on March 27, 2009.

- Wilder, Julie, ed. 1999. Wiigwaaskingaa / Land of birch trees: Ojibwe stories by Arthur J. McGregor. Ojibwe editor Mary E. Wemigwans. Hobbema, AB: Blue Moon Publishing. ISBN 0-9685103-0-2

- Wolfart, H. Christoph. 1989. "Lahontan's best-seller." Historiographia Linguistica 16: 1–24.

Further reading

[edit]- Cappel, Constance. 2007, The Smallpox Genocide of the Odawa Tribe at L'Arbre Croche, 1763: The History of a Native American People, Edwin Mellen Press.

- Norris, Mary Jane. 1998. Canada's Aboriginal languages. Canadian Social Trends (Winter): 8–16

- Rhodes, Richard A. 1979. "Some aspects of Ojibwa discourse." W. Cowan, ed., Papers of the 10th Algonquian Conference, pp. 102–117. Ottawa: Carleton University. ISBN 0-7709-0059-3

- Rhodes, Richard A. 1980. "On the semantics of the instrumental finals in Ojibwa." W. Cowan, ed., Papers of the 11th Algonquian Conference, pp. 183–197. Ottawa: Carleton University. ISBN 0-7709-0076-3

- Rhodes, Richard A. 1981. "On the Semantics of the Ojibwa Verbs of Breaking." W. Cowan, ed., Papers of the 12th Algonquian Conference, pp. 47–56. Ottawa: Carleton University. ISBN 0-7709-0116-6

- Rhodes, Richard A. 1982. "Algonquian Trade Languages." W. Cowan, ed., Papers of the 13th Algonquian Conference, pp. 1–10. Ottawa: Carleton University. ISBN 0-7709-0123-9

- Rhodes, Richard A. 1983. "Some Comments on Ojibwa Ethnobotany." W. Cowan, ed., Actes du 14e Congrès des Algonquinistes, pp. 307–320. Ottawa: Carleton University. ISBN 0-7709-0126-3

- Rhodes, Richard A. 1984. "Baseball, Hotdogs, Apple Pie, and Chevrolets." W. Cowan, ed., Papers of the 15th Algonquian Conference, pp. 373–388. Ottawa: Carleton University. ISBN 0-7709-0165-4

- Rhodes, Richard A. 1985. "Metaphor and Extension in Ojibwa." W. Cowan, ed., Papers of the 16th Algonquian Conference, pp. 161–169. Ottawa: Carleton University. ISSN 0831-5671

- Rhodes, Richard A. 1988. "Ojibwa Politeness and Social Structure." W. Cowan, ed., Papers of the 19th Algonquian Conference, pp. 165–174. Ottawa: Carleton University. ISSN 0831-5671

- Rhodes, Richard A. 1991. "On the Passive in Ojibwa." W. Cowan, ed., Papers of the 22nd Algonquian Conference, pp. 307–319. Ottawa: Carleton University. ISSN 0831-5671

- Rhodes, Richard A. 1998. "The Syntax and Pragmatics of Ojibwe Mii." D. H. Pentland, ed., Papers of the 29th Algonquian Conference, pp. 286–294. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba. ISSN 0831-5671

- Rhodes, Richard. 2002. "Multiple Assertions, Grammatical Constructions, Lexical Pragmatics, and the Eastern Ojibwe-Chippewa-Ottawa Dictionary." William Frawley, Kenneth C. Hill, & Pamela Munro, eds., Making Dictionaries: Preserving Indigenous Languages of the Americas, pp. 108–124. Berkeley: University of California Press. 108-124. ISBN 978-0-520-22996-9

- Rhodes, Richard A. 2004. "Alexander Francis Chamberlain and the language of the Mississaga Indians of Skugog." H.C. Wolfart, ed., Papers of the 35th Algonquian Conference, pp. 363–372. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba. ISSN 0831-5671

- Rhodes, Richard. 2005. "Directional pre-verbs in Ojibwe and the registration of path." H.C. Wolfart, ed., Papers of the Thirty-sixth Algonquian Conference, pp. 371–382. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba. 371-382. ISSN 0831-5671

- Toulouse, Isadore. 2008. Kidwenan: An Ojibwe language book. Third Edition. Southampton, ON: Ningwakwe Press. ISBN 978-1-896832-96-8

- Williams, Shirley I. 2002. Gdi-nweninaa: Our sound, our voice. Peterborough, ON: Neganigwane. ISBN 0-9731442-1-1

External links

[edit]- "Native American Audio Collections: Ottawa". American Philosophical Society. Archived from the original on 2013-08-14. Retrieved 2013-05-20.

- Anishnaabemdaa, produced by the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians, Anishinaabemowin Program

- The revitalization of the Nishnaabemwin Language project at Trent University

- Portions of the Book of Common Prayer in Ottawa

- OLAC resources in and about the Ottawa language

- An online Nishnaabemwin Dictionary

Ottawa dialect

View on GrokipediaClassification and Status

Linguistic Classification

The Ottawa dialect, also known as Odawa, belongs to the Central Algonquian subgroup of the Algic language family and constitutes a distinct variety within the Ojibwe–Potawatomi–Ottawa (O-P-O) dialect continuum. This continuum represents a chain of interrelated speech forms spoken by Anishinaabe communities across the Great Lakes region, where gradual variations in phonology, lexicon, and grammar create a spectrum rather than sharp boundaries between Ojibwe, Potawatomi, and Ottawa.[10] Key lexical features set Ottawa apart from other varieties, including forms such as noos 'my father' (distinct from other Ojibwe forms) and nbiish 'water' (with suffixation, versus the general Algonquian nibi). Vowel variations are also evident, as in giishpinadaaso 'buys' (contrasting with some Chippewa forms). These features highlight Ottawa's lexical divergence while maintaining core Algonquian structures shared across the continuum.[10] Mutual intelligibility is high between Ottawa and adjacent dialects like Southwestern Ojibwe, facilitated by overlapping lexicon such as odaanaang for spatial expressions (shared with Southwestern forms, though varying as ishkweyaang in some contexts). Intelligibility is lower with Eastern Ojibwe due to cumulative differences in vowel systems and syncope patterns.[10] Terminologically, the overarching language is designated Nishnaabemwin across Ojibwe varieties, encompassing cultural and linguistic identity for Anishinaabe speakers, while Odawaamwin specifically denotes the Ottawa dialect, reflecting its localized usage in communities like those in Michigan and Ontario.[10]Endangerment and Speaker Demographics

The Ottawa dialect is classified as severely endangered by UNESCO's Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger (third edition, 2010). As of the 2021 censuses, approximately 5,100 people reported some ability to speak Ottawa (total with proficiency), with around 4,900 in the United States and 220 in Canada; however, fluent first-language speakers number about 2,000, mostly elders over 60, while younger generations show low proficiency or passive understanding.[11][12] Key factors driving this endangerment include historical assimilation policies, such as U.S. and Canadian residential school systems that suppressed indigenous languages, alongside urbanization that promotes English dominance in daily life and significant gaps in intergenerational transmission, where parents rarely speak Ottawa to children.[13][14] Regional variations underscore the severity, with only 3 fluent speakers remaining in the Ottawa Tribe of Oklahoma communities as of 2024.Geographic Distribution

Current Communities

The Ottawa dialect, also known as Odawa, is currently spoken in several key communities across southern Ontario, northern Michigan, and smaller, scattered groups in Oklahoma, reflecting the historical dispersal of Odawa people while maintaining ties to Anishinaabe cultural practices.[15][16][17] In Canada, the largest concentration of speakers resides in the Wikwemikong Unceded Territory on Manitoulin Island, a community of over 7,200 Anishinaabek members with approximately 2,900 living on the territory, where Odawa functions as the ancestral language integral to cultural identity and intergenerational transmission.[16] This territory emphasizes Odawa through community-led initiatives, including digital tools for learning basic vocabulary and phrases, underscoring its role in preserving Anishinaabe heritage amid elder-led oral traditions.[16] In the United States, northern Michigan hosts Odawa communities with active language revitalization efforts, particularly through the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians around Petoskey and Harbor Springs, where the language department supports its use in tribal governance, cultural events, and education.[15] The Burt Lake Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, a state-recognized group near Burt Lake, contributes to localized cultural continuity despite ongoing recognition efforts.[18] Smaller communities, such as the Ottawa Tribe of Oklahoma in Miami, Oklahoma, include a limited number of fluent speakers who engage with the dialect through shared Anishinaabe resources, though usage remains minimal compared to northern groups.[17] Overall, the Ottawa dialect has approximately 1,100 speakers as of the 2021 census, with most fluent speakers being elders. Dialectal variations among these communities are subtle, primarily in lexical choices influenced by local histories and interactions; for example, Michigan Odawa often retains more archaic forms in vocabulary related to traditional activities, distinguishing it from Ontario variants.[10][19] In contemporary settings, the language is predominantly employed in ceremonial practices, familial conversations, and restricted public spheres like community gatherings and educational programs, fostering cultural cohesion even as overall speaker numbers continue to decline.[15][16][18]Historical Population Movements

Prior to European contact in the 16th century, Ottawa (Odawa) communities occupied territories across the Great Lakes region, spanning from the east coast of Georgian Bay and Manitoulin Island in present-day Ontario to the Bruce Peninsula and southward into Michigan's Lower Peninsula.[20] These semisedentary groups established villages near water bodies, including islands and river forks, relocating periodically to allow resource regeneration, with a focus on areas around northern Lake Huron and Lake Michigan.[21] Their range facilitated seasonal movements for hunting, fishing, and trade along established routes.[22] In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Beaver Wars (1640–1701) profoundly disrupted Ottawa populations, as conflicts with the Iroquois over fur trade control drove westward migrations from eastern Great Lakes areas to refuges in western Michigan and Wisconsin, including Door County.[23] Alliances with the French, formed through fur trade partnerships, provided some protection and encouraged further shifts to strategic locations like the Straits of Mackinac, Detroit, and southern Michigan's Lower Peninsula, where Ottawa bands settled in mixed villages near French posts.[24] The Treaty of Greenville in 1795, signed by Ottawa representatives alongside other tribes, ceded vast lands in Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan to the United States following the Northwest Indian War, compelling some groups to relocate to reserved areas in Ohio and Indiana amid escalating settler encroachment.[25] The 19th and early 20th centuries saw intensified displacements due to U.S. and Canadian policies. Under the Indian Removal Act of 1830, Ottawa bands from Ohio were forcibly relocated to Kansas in the 1830s, with the final groups arriving by 1839, resulting in significant population losses from disease and hardship during transit.[21] In 1867, the Kansas Ottawa sold their lands and moved to Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma, purchasing acreage from the Shawnee amid further federal pressures.[21] In Canada, post-1850 reserve consolidations under treaties like the Robinson-Huron Treaty of 1850 confined remaining Odawa communities to designated lands, such as Manitoulin Island, limiting traditional mobility and consolidating populations on smaller territories.[26] These migrations and isolations had notable linguistic consequences for the Ottawa dialect, as separated groups developed distinct innovations.Phonology

Consonants

The Ottawa dialect of Ojibwe possesses a consonant inventory consisting of 17 phonemes, characterized by a fortis-lenis contrast that distinguishes voiceless, tense consonants from their voiced or lax counterparts.[27] This system includes stops (/p, t, k, ʔ/, fortis; /b, d, g/, lenis), affricates (/tʃ/, fortis; /dʒ/, lenis), fricatives (/s, ʃ, h/, fortis; /z, ʒ/, lenis), nasals (/m, n/), and approximants (/w, j/).[28] The following table presents the consonant phonemes organized by place and manner of articulation:| Manner\Place | Bilabial | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Velar | Glottal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stops (fortis) | p | t | k | ʔ | |

| Stops (lenis) | b | d | g | ||

| Affricates (fortis) | tʃ | ||||

| Affricates (lenis) | dʒ | ||||

| Fricatives (fortis) | s | ʃ | h | ||

| Fricatives (lenis) | z | ʒ | |||

| Nasals | m | n | |||

| Approximants | w | j |

Vowels and Syncope

The Ottawa dialect of Ojibwe maintains a core oral vowel inventory of seven phonemes, comprising three short vowels /i, o, a/ and four long vowels /iː, oː, aː, eː/, where length serves as a phonemic contrast affecting syllable weight and prosody. The short vowels are generally lax and less peripheral, with /i/ realized as [ɪ] or depending on stress, /o/ as [ɔ] or , and /a/ as a distinctive centralized mid vowel akin to English "uh" [ə] or [ʌ], a quality shift particularly characteristic of Ottawa that sets it apart from other Ojibwe dialects. Long vowels, by contrast, are tense and more stable: /iː/ [iː], /oː/ [oː], /aː/ [ɑː], and /eː/ [eː]. Nasalized vowels arise primarily through contextual assimilation before nasal consonants, functioning as allophones of their oral counterparts rather than independent phonemes, though some analyses note limited contrastive nasalization on long vowels in specific environments like stem-final positions.[27] Vowel quality in Ottawa exhibits notable shifts, especially in unstressed positions, where short vowels undergo reduction toward a central schwa-like quality [ə], contributing to the dialect's compact and syncopated auditory profile. The centralized /a/ remains a hallmark, often serving as the default realization for underlying short /a/ in non-prominent syllables, and it resists full deletion more than /i/ or /o/ in certain contexts. These reductions are phonetically motivated by the dialect's iambic rhythm, which favors vowel weakening in metrically weak positions to enhance word-level stress patterns.[27][31] A defining phonological process in Ottawa is vowel syncope, the systematic deletion of short vowels within trisyllabic prosodic feet, particularly those in open syllables and metrically unstressed positions, which streamlines word forms and increases consonant clustering. For instance, the noun for "spirit," underlyingly /manidoː/ (from Proto-Algonquian *manetowa), surfaces as /mnidoː/ after the initial short vowel deletes, yielding a disyllabic structure. This rule applies obligatorily in the derivational morphology stratum but may be optional or blocked in the inflectional stratum to avoid phonotactically illicit clusters, such as those exceeding two obstruents; exceptions occur in underived lexical items or loanwords that preserve the full vowel sequence for historical or perceptual reasons.[28][27] Syncope is tightly governed by prosodic structure, with primary stress assigned in a quantity-sensitive manner to the penultimate syllable of the prosodic word, treating long vowels as heavy and attracting stress while rendering preceding short vowels vulnerable to deletion. This penultimate stress pattern, inherited from earlier stages of the language, interacts with foot formation to target weak syllables in iambic (weak-strong) groupings, often the first of three syllables in a word. The resulting consonant clusters post-syncope are generally resolvable within Ottawa's phonotactics, though they may trigger minor assimilations with adjacent consonants. Overall, these processes underscore Ottawa's innovative phonological economy, distinguishing it from less syncopating Ojibwe varieties.[28]Grammar

Morphology

Ottawa noun morphology distinguishes between animate and inanimate genders, a hallmark of Algonquian languages, where animate nouns typically refer to living beings such as people, animals, birds, trees like wiigwaasatig 'birch tree', and certain spiritually significant items, while inanimate nouns encompass most non-living objects, natural features like nibi 'water', and human-made items like onaagan 'dish'.[7] Number is marked by suffixes: singular forms are unmarked, animate plurals take -ag as in waagosh 'fox' becoming waagoshag 'foxes', and inanimate plurals take -an as in jiimaan 'canoe' becoming jiimaanan 'canoes'.[7] Obviation, which demotes a third-person participant to avoid hierarchy conflicts in discourse, is realized through suffixes primarily on animate nouns: the obviative singular uses -an as in waagoshan 'the other fox', while inanimate nouns often lack distinct obviative marking or align with the plural -an form.[32] Verb morphology in Ottawa is highly inflectional, organized into four major conjugation classes based on transitivity and animacy: animate intransitive (AI or VAI) verbs describe actions by animate subjects, such as michaa 'it is big' in AI form; inanimate intransitive (II or VII) verbs describe states of inanimate subjects, like michaa in VII form; transitive inanimate (TI or VTI) verbs involve an animate subject acting on an inanimate object; and transitive animate (TII or VTA) verbs involve animate subject and object interactions.[33] Person is indicated by prefixes, including ni- for first singular as in nimichaa 'I am big', gi- for second singular, and o- for third singular, with suffixes marking additional persons and numbers in paradigms.[34] Tense and aspect are primarily conveyed through preverbs, though certain modes use suffixes; for instance, future intent is marked by preverbs such as wii- or da- in independent indicative forms to indicate planned actions.[35] Derivational morphology employs affixes to create new words from roots or stems, including nominalizers like -win that form agent or locative nouns, such as deriving terms for persons associated with places or actions, and verbalizers like -aa that convert nouns into verbs, often indicating possession or action related to the base. Compounding is productive, combining noun and verb roots to form complex terms; for example, wanihiigewinini 'trapper' compounds elements related to trapping with 'man' to express the profession.[10] Possession, often inalienable for body parts and kin, is marked by prefixes identical to verb person markers: ni- for 'my' as in nindaanis 'my child', gi- for 'your', and o- for 'his/her/their', with suffixes for plural possessors like -waa.[36] Diminutives convey smallness or endearment via the suffix -ns or -ens, attached to stems as in zhiishiibiins 'duckling' from zhiishiib 'duck'.Syntax