Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Industrial Workers of the World

View on Wikipedia

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), whose members are nicknamed "Wobblies",[b] is an international labor union founded in Chicago, Illinois, United States, in 1905. Its ideology combines general unionism with industrial unionism, as it is a general union, subdivided between the various industries which employ its members. The philosophy and tactics of the IWW are described as "revolutionary industrial unionism", with ties to socialist,[6] syndicalist, and anarchist labor movements.

Key Information

In the 1910s and early 1920s, the IWW achieved many of its short-term goals, particularly in the American West, and cut across traditional guild and union lines to organize workers in a variety of trades and industries. At their peak in August 1917, IWW membership was estimated at more than 150,000, with active wings in the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.[7] However, the extremely high rate of IWW membership turnover during this era (estimated at 133% between 1905 and 1915) makes it difficult for historians to state membership totals with any certainty, as workers tended to join the IWW in large numbers for relatively short periods (e.g., during labor strikes and periods of generalized economic distress).[8][9]

Membership declined dramatically in the late 1910s and 1920s. There were conflicts with other labor groups, particularly the American Federation of Labor (AFL), which regarded the IWW as too radical, while the IWW regarded the AFL as too conservative and opposed their decision to divide workers on the basis of their trades.[10] Membership also declined due to government crackdowns on radical, anarchist, and socialist groups during the First Red Scare after World War I. In Canada, the IWW was outlawed by the federal government by an Order in Council on September 24, 1918.[11]

Likely the most decisive factor in the decline in IWW membership and influence was a 1924 schism in the organization, from which the IWW never fully recovered.[10][12] During the 1950s, the IWW faced near-extinction due to persecution under the Second Red Scare,[13] although the union would later experience a resurgence in the context of the New Left in the 1960s and 1970s.[14]

The IWW promotes the concept of "One Big Union", and contends that all workers should be united as a social class to supplant capitalism and wage labor with industrial democracy.[15] It is known for the Wobbly Shop model of workplace democracy, through which workers elect their own managers[16] and other forms of grassroots democracy (self-management) are implemented. The IWW does not require its members to work in a represented workplace,[17] nor does it exclude membership in another labor union.[18]

United States

[edit]1905–1950

[edit]Foundation

[edit]

The first meeting to plan the IWW was held in Chicago in 1904. The seven attendees were Clarence Smith and Thomas J. Hagerty of the American Labor Union, George Estes and W. L. Hall of the United Brotherhood of Railway Employees, Isaac Cowan of the U.S. branch of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers, William E. Trautmann of the United Brewery Workmen and Julian E. Bagley WW1 veteran and author. Eugene Debs, formerly of the American Railway Union, and Charles O. Sherman of the United Metal Workers were involved but did not attend the meeting.[19]

The IWW was officially founded in Chicago, Illinois in June 1905. A convention was held of 200 socialists, anarchists, Marxists (primarily members of the Socialist Party of America and Socialist Labor Party of America), and radical trade unionists from all over the United States (mainly the Western Federation of Miners) who strongly opposed the policies of the American Federation of Labor (AFL). The IWW opposed the AFL's acceptance of capitalism and its refusal to include unskilled workers in craft unions.[20]

The convention took place on June 27, 1905, and was referred to as the "Industrial Congress" or the "Industrial Union Convention". It was later known as the First Annual Convention of the IWW.[9]: 67 In an opening speech, William D. ("Big Bill") Haywood declared:

This is the Continental Congress of the working class. We are here to confederate the workers of this country into a working-class movement that shall have for its purpose the emancipation of the working class from the slave bondage of capitalism.[21]

The IWW's founders included Haywood, James Connolly, Daniel De Leon, Eugene V. Debs, Thomas Hagerty, Lucy Parsons, Mary Harris "Mother" Jones, Frank Bohn, William Trautmann, Vincent Saint John, Ralph Chaplin, and many others.

The IWW aimed to promote worker solidarity in the revolutionary struggle to overthrow the employing class; its motto was "an injury to one is an injury to all". They saw this as an improvement upon the Knights of Labor's creed, "an injury to one is the concern of all" which the Knights had spoken out in the 1880s. In particular, the IWW was organized because of the belief among many unionists, socialists, anarchists, Marxists, and radicals that the AFL not only had failed to effectively organize the U.S. working class, but it was causing separation rather than unity within groups of workers by organizing according to narrow craft principles. The Wobblies believed that all workers should organize as a class, a philosophy that is still reflected in the Preamble to the current IWW Constitution:

The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of the working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life.

Between these two classes a struggle must go on until the workers of the world organize as a class, take possession of the means of production, abolish the wage system, and live in harmony with the Earth.

We find that the centering of the management of industries into fewer and fewer hands makes the trade unions unable to cope with the ever growing power of the employing class. The trade unions foster a state of affairs which allows one set of workers to be pitted against another set of workers in the same industry, thereby helping defeat one another in wage wars. Moreover, the trade unions aid the employing class to mislead the workers into the belief that the working class have interests in common with their employers.

These conditions can be changed and the interest of the working class upheld only by an organization formed in such a way that all its members in any one industry, or in all industries if necessary, cease work whenever a strike or lockout is on in any department thereof, thus making an injury to one an injury to all.

Instead of the conservative motto, "A fair day's wage for a fair day's work," we must inscribe on our banner the revolutionary watchword, "Abolition of the wage system."

It is the historic mission of the working class to do away with capitalism. The army of production must be organized, not only for everyday struggle with capitalists, but also to carry on production when capitalism shall have been overthrown. By organizing industrially we are forming the structure of the new society within the shell of the old.[15]

One of the IWW's most important contributions to the labor movement and broader push of social justice was that, when founded, it was the only American union to welcome all workers, including women, immigrants, African Americans and Asians, into the same organization. Many of its early members were immigrants, and some, such as Carlo Tresca, Joe Hill and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, rose to prominence in the leadership. Finns formed a sizable portion of the immigrant IWW membership. "Conceivably, the number of Finns belonging to the I.W.W. was somewhere between five and ten thousand."[22] The Finnish-language newspaper of the IWW, Industrialisti, published in Duluth, Minnesota, a center of the mining industry, was the union's only daily paper. At its peak, it ran 10,000 copies per issue. Another Finnish-language Wobbly publication was the monthly Tie Vapauteen ("Road to Freedom"). Also of note was the Finnish IWW educational institute, the Work People's College in Duluth, and the Finnish Labour Temple in Port Arthur, Ontario, Canada, which served as the IWW Canadian administration for several years. Further, many Swedish immigrants, particularly those blacklisted after the 1909 Swedish General Strike, joined the IWW and set up similar cultural institutions around the Scandinavian Socialist Clubs. This in turn exerted a political influence on the Swedish labor movement's left, that in 1910 formed the Syndicalist union SAC which soon contained a minority seeking to mimick the tactics and strategies of the IWW.[23]

Organization

[edit]

The few own the many because they possess the means of livelihood of all ... The country is governed for the richest, for the corporations, the bankers, the land speculators, and for the exploiters of labor. The majority of mankind are working people. So long as their fair demands – the ownership and control of their livelihoods – are set at naught, we can have neither men's rights nor women's rights. The majority of mankind is ground down by industrial oppression in order that the small remnant may live in ease.

The IWW first attracted attention in Goldfield, Nevada, in 1906 and during the Pressed Steel Car Strike of 1909.[25]

By 1912, the organization had around 25,000 members.[26]

Geography

[edit]In its first decades, the IWW created more than 900 unions located in more than 350 cities and towns in 38 states and territories of the United States and five Canadian provinces.[27] Throughout the country, there were 90 newspapers and periodicals affiliated with the IWW, published in 19 different languages. Cartoons were a major part of IWW publications. Produced by unpaid rank and file members they satirised the union's opponents and helped spread its messages in various forms, including 'stickerettes'. The most well-known IWW cartoon character, Mr Block, was created by Ernest Riebe and was made the subject of a Joe Hill song.[28] Members of the IWW were active throughout the country and were involved in the Seattle General Strike of 1919,[29] were arrested or killed in the Everett Massacre,[30] organized among Mexican workers in the Southwest,[31] and became a large and powerful longshoremen's union in Philadelphia.[32]

IWW versus AFL Carpenters, Goldfield, Nevada, 1906-1907

[edit]Resisting IWW domination in the gold mining boom town of Goldfield, Nevada was the AFL-affiliated Carpenters Union. In March 1907, the IWW demanded that the mines deny employment to AFL Carpenters, which led mine owners to challenge the IWW. The mine owners banded together and pledged not to employ any IWW members. The mine and business owners of Goldfield staged a lockout, vowing to remain shut until they had broken the power of the IWW. The lockout prompted a split within the Goldfield workforce, between conservative and radical union members.[33]

Haywood trial and Western Federation of Miners exit

[edit]Leaders of the Western Federation of Miners such as Bill Haywood and Vincent St. John were instrumental in forming the IWW, and the WFM affiliated with the new union organization shortly after the IWW was formed. The WFM became the IWW's "mining section". Many in the rank and file of the WFM were uncomfortable with the open radicalism of the IWW and wanted the WFM to maintain its independence. Schisms between the WFM and IWW had emerged at the annual IWW convention in 1906, when a majority of WFM delegates walked out.[9]

When WFM executives Bill Haywood, George Pettibone, and Charles Moyer were accused of complicity in the murder of former Idaho governor Frank Steunenberg, the IWW used the case to raise funds and support and paid for the legal defense. Even the not guilty verdicts worked against the IWW, because the IWW was deprived of martyrs, and at the same time, a large portion of the public remained convinced of the guilt of the accused.[34]

Bill Haywood for a time remained a member of both organizations. His murder trial had made Haywood a celebrity, and he was in demand as a speaker for the WFM. His increasingly radical speeches became more at odds with the WFM, and in April 1908, the WFM announced that the union had ended Haywood's role as a union representative. Haywood left the WFM and devoted all his time to organizing for the IWW.[9]: 216–217

Historian Vernon H. Jensen has asserted that the IWW had a "rule or ruin" policy, under which it attempted to wreck local unions which it could not control. From 1908 to 1921, Jensen and others have written, the IWW attempted to win power in WFM locals which had once formed the federation's backbone. When it could not do so, IWW agitators undermined WFM locals, which caused the national union to shed nearly half its membership.[35][36][37][38]

IWW versus the Western Federation of Miners

[edit]The Western Federation of Miners left the IWW in 1907, but the IWW wanted the WFM back. The WFM had made up about a third of the IWW membership, and the western miners were tough union men, and good allies in a labor dispute. In 1908, Vincent St. John tried to organize a stealth takeover of the WFM. He wrote to WFM organizer Albert Ryan, encouraging him to find reliable IWW sympathizers at each WFM local, and have them appointed delegates to the annual convention by pretending to share whatever opinions of that local needed to become a delegate. Once at the convention, they could vote in a pro-IWW slate. St. Vincent promised: "once we can control the officers of the WFM for the IWW, the big bulk of the membership will go with them." But the takeover did not succeed.[39]

According to several historians, the 1913 El Paso smelters' strike marked one of the first instances of direct competition between the IWW and the WFM, as the two unions competed to organize workers on strike against the American Smelting and Refining Company's local smelter.[40][41][42] In 1914, Butte, Montana, erupted into a series of riots as miners dissatisfied with the Western Federation of Miners local at Butte formed a new union, and demanded that all miners join the new union, or be subject to beatings or worse. Although the new rival union had no affiliation with the IWW, it was widely seen as IWW-inspired. The leadership of the new union contained many who were members of the IWW or agreed with the IWW's methods and objectives. The new union failed to supplant the WFM, and the ongoing fight between the two resulted in the copper mines of Butte, longtime union strongholds for the WFM, becoming open shops, and the mine owners recognized no union from 1914 until 1934.[43]

Versus United Mine Workers, Scranton, Pennsylvania, 1916

[edit]The IWW clashed with the United Mine Workers union in April 1916, when the IWW picketed the anthracite mines around Scranton, Pennsylvania, intending, by persuasion or force, to keep UMWA members from going to work. The IWW considered the UMWA too reactionary, because the United Mine Workers negotiated contracts with the mine owners for fixed time periods; the IWW considered that contracts hindered their revolutionary goals. In what a contemporary writer pointed out was a complete reversal of their usual policy, UMWA officials called for police to protect United Mine Workers members who wished to cross the picket lines. The Pennsylvania State Police arrived in force, prevented picket line violence, and allowed the UMWA members to peacefully pass through the IWW picket lines.[9][44]

Bisbee Deportation

[edit]

In November 1916, the 10th convention of the IWW authorized an organizing drive in the Arizona copper mines. Copper was a vital war commodity, so mines were working day and night. During the first months of 1917, thousands joined the Metal Mine Workers' Union #800. The focus of the organizing drive was Bisbee, Arizona, a small town near the Mexican border. Nearly 5000 miners worked in Bisbee's mines. On June 27, 1917, Bisbee's miners went on strike. The strike was effective and non-violent. Demands included the doubling of pay for surface workers, most of them recent immigrants from Mexico, as well as changes in working conditions to make the mines safer. The six-hour day was raised agitationally but held in abeyance. In the early hours of July 12, hundreds of armed vigilantes rounded up nearly two thousand strikers, of whom 1186 were deported in cattle cars and dumped in the desert of New Mexico. In the following days, hundreds more were ordered to leave. The strike was broken at gunpoint.[45]

Other organizing drives

[edit]

Between 1915 and 1917, the IWW's Agricultural Workers Organization (AWO) organized more than a hundred thousand migratory farm workers throughout the Midwest and western United States.[46]

Building on the success of the AWO, the IWW's Lumber Workers Industrial Union (LWIU) used similar tactics to organize lumberjacks and other timber workers, both in the deep South and the Pacific Northwest of the United States and Canada, between 1917 and 1924. The IWW lumber strike of 1917 led to the eight-hour day and vastly improved working conditions in the Pacific Northwest. Though mid-century historians credited the US Government and "forward thinking lumber magnates" for agreeing to such reforms, an IWW strike forced these concessions.[47]

Where the IWW did win strikes, such as in Lawrence, they often found it hard to hold onto their gains. The IWW of 1912 disdained collective bargaining agreements and preached instead the need for constant struggle against the boss on the shop floor. It proved difficult to maintain that sort of revolutionary enthusiasm against employers. In Lawrence, the IWW lost nearly all of its membership in the years after the strike, as the employers wore down their employees' resistance and eliminated many of the strongest union supporters. In 1938, the IWW voted to allow contracts with employers.[48]

Government suppression

[edit]

The IWW's efforts were met with "unparalleled" resistance from Federal, state and local governments in America;[10] from company management and labor spies, and from groups of citizens functioning as vigilantes. In 1914, Wobbly Joe Hill (born Joel Hägglund) was accused of murder in Utah and, on what many regarded as limited and insufficient evidence, was executed in 1915.[49][50] On November 5, 1916, at Everett, Washington, a group of deputized businessmen led by Sheriff Donald McRae attacked Wobblies on the steamer Verona, killing at least five union members[51] (six more were never accounted for and probably were lost in Puget Sound). Two members of the police force—one a regular officer and another a deputized citizen from the National Guard Reserve—were killed, probably by "friendly fire".[52] At least five Everett civilians were wounded.[53]

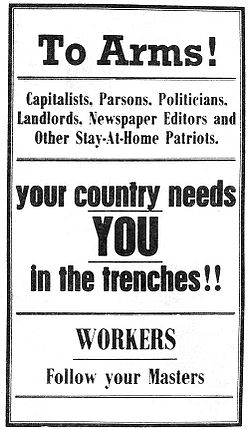

Many IWW members opposed United States participation in World War I. The organization passed a resolution against the war at its convention in November 1916.[54]: 241 This echoed the view, expressed at the IWW's founding convention, that war represents struggles among capitalists in which the rich become richer, and the working poor all too often die at the hands of other workers.

An IWW newspaper, the Industrial Worker, wrote just before the U.S. declaration of war: "Capitalists of America, we will fight against you, not for you! There is not a power in the world that can make the working class fight if they refuse." Yet when a declaration of war was passed by the U.S. Congress in April 1917, the IWW's general secretary-treasurer Bill Haywood became determined that the organization should adopt a low profile in order to avoid perceived threats to its existence. The printing of anti-war stickers was discontinued, stockpiles of existing anti-war documents were put into storage, and anti-war propagandizing ceased as official union policy. After much debate on the General Executive Board, with Haywood advocating a low profile and GEB member Frank Little championing continued agitation, Ralph Chaplin brokered a compromise agreement. A statement was issued that denounced the war, but IWW members were advised to channel their opposition through the legal mechanisms of conscription. They were advised to register for the draft, marking their claims for exemption "IWW, opposed to war."[54]: 242–244

During World War I, the U.S. government moved strongly against the IWW. On September 5, 1917, U.S. Department of Justice agents made simultaneous raids on dozens of IWW meeting halls across the country.[36]: 406 Minutes books, correspondence, mailing lists, and publications were seized, with the U.S. Department of Justice removing five tons of material from the IWW's General Office in Chicago alone.[36]: 406

Based in large measure on the documents seized September 5, one hundred and sixty-six IWW leaders were indicted by a Federal Grand Jury in Chicago for conspiring to hinder the draft, encourage desertion, and intimidate others in connection with labor disputes, under the new Espionage Act.[36]: 407 One hundred and one went on trial en masse before Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis in 1918. Their lawyer was George Vanderveer of Seattle.[55]

In 1917, during an incident known as the Tulsa Outrage, a group of black-robed Knights of Liberty tarred and feathered seventeen members of the IWW in Oklahoma. The attack was cited as revenge for the Green Corn Rebellion, a preemptive attack caused by fear of an impending attack on the oil fields and as punishment for not supporting the war effort. The IWW members had been turned over to the Knights of Liberty by local authorities after they were beaten, arrested at their headquarters and convicted of the crime of vagrancy. Five other men who testified in defense of the Wobblies were also fined by the court and subjected to the same torture and humiliations at the hands of the Knights of Liberty.[56][57][58][59]

In 1919, an Armistice Day parade by the American Legion in Centralia, Washington, turned into a fight between legionnaires and IWW members in which four legionnaires were shot. Which side initiated the violence of the Centralia massacre is disputed, though there had been previous attacks on the IWW hall and businessmen's association had made threats against union members. A number of IWWs were arrested, one of whom, Wesley Everest, was lynched by a mob that night.[60]

A bronze plaque honoring the IWW members imprisoned and lynched following the Centralia Tragedy was dedicated in the city's George Washington Park on November 11, 2023. A request was delivered to Washington Governor Inslee requesting posthumous pardons for the eight IWW members who were convicted.[61] A rededication was held in June 2024 after the plaque was installed on a 7,500 lb (3,400 kg) granite block base. The color and carved style was an intentional match of the base of the American Legion memorial, The Sentinel. The $20,000 funding for the overall project, and the labor involved, was done mostly by union organizations or workers.[62]

Organizational schism and aftermath

[edit]IWW quickly recovered from the setbacks of 1919 and 1920, with membership peaking in 1923 (58,300 estimated by dues paid per capita, though membership was likely somewhat higher as the union tolerated delinquent members).[63] But recurring internal debates, especially between those who sought either to centralize or decentralize the organization, ultimately brought about the IWW's 1924 schism.[64]

The twenties witnessed the defection of hundreds of Wobbly leaders (including Harrison George, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, John Reed, George Hardy, Charles Ashleigh, Earl Browder and, in his Soviet exile, Bill Haywood) and, following a path recounted by Fred Beal,[65] thousands of Wobbly rank-and-filers to the Communists and Communist organizations.[66][67]

At the beginning of the 1949 Smith Act trials, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover was disappointed when prosecutors indicted fewer CPUSA members than he had hoped, and—recalling the arrests and convictions of over one hundred IWW leaders in 1917—complained to the Justice Department, stating, "the IWW as a subversive menace was crushed and has never revived. Similar action at this time would have been as effective against the Communist Party and its subsidiary organizations."[68]

1950–2000

[edit]Taft–Hartley Act

[edit]

After the passage of the Taft-Hartley Act in 1946 by Congress, which called for the removal of Communist union leadership, the IWW experienced a loss of membership as differences of opinion occurred over how to respond to the challenge. In 1949, US Attorney General Tom C. Clark[69] placed the IWW on the Attorney General's List of Subversive Organizations[70] in the category of "organizations seeking to change the government by unconstitutional means" under Executive Order 9835, which offered no means of appeal, and which excluded all IWW members from Federal employment and federally subsidized housing programs (this order was revoked by Executive Order 10450 in 1953).

At this time, the Cleveland local of the Metal and Machinery Workers Industrial Union (MMWIU) was the strongest IWW branch in the United States. Leading figures such as Frank Cedervall, who had helped build the branch up for over ten years, were concerned about the possibility of raiding from AFL-CIO unions if the IWW had its legal status as a union revoked. In 1950, Cedervall led the 1500-member MMWIU national organization to split from the IWW, as the Lumber Workers Industrial Union had almost 30 years earlier. This act did not save the MMWIU. Despite its brief affiliation with the Congress of Industrial Organizations, it was raided by the AFL and CIO and defunct by the late 1950s, less than ten years after separating from the IWW.[71]

The loss of the MMWIU, at the time the IWW's largest industrial union, was almost a deathblow to the IWW. The union's membership fell to its lowest level in the 1950s during the Second Red Scare, and by 1955, the union's fiftieth anniversary, it was near extinction, though it still appeared on government lists of Communist-led groups.[13]

1960s rejuvenation

[edit]The 1960s civil rights movement, anti-war protests, and various university student movements brought new life to the IWW, albeit with many fewer new members than the great organizing drives of the early part of the 20th century.

The first signs of new life for the IWW in the 1960s were organizing efforts among students in San Francisco and Berkeley, which were hotbeds of student radicalism at the time. This targeting of students resulted in a Bay Area branch of the union with over a hundred members in 1964, almost as many as the union's total membership in 1961. Wobblies old and new united for one more "free speech fight": Berkeley's Free Speech Movement. Riding on this high, the decision in 1967 to allow college and university students to join the Education Workers Industrial Union (IU 620) as full members spurred campaigns in 1968 at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, and the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.[72]: 13 The IWW sent representatives to Students for a Democratic Society conventions in 1967, 1968, and 1969, and as the SDS collapsed into infighting, the IWW gained members fleeing this discord. These changes had a profound effect on the union, which by 1972 had 67% of members under the age of 30, with a total of nearly 500 members.[72]: 14

The IWW's links to the 1960s counterculture led to organizing campaigns at counterculture businesses, as well as a wave of over two dozen co-ops affiliating with the IWW under its Wobbly Shop model in the 1960s to 1980s. These businesses were primarily in printing, publishing, and food distribution, from underground newspapers and radical print shops to community co-op grocery stores. Some of the printing and publishing industry co-ops and job shops included Black & Red (Detroit), Glad Day Press (New York), RPM Press (Michigan), New Media Graphics (Ohio), Babylon Print (Wisconsin), Hill Press (Illinois), Lakeside (Madison, Wisconsin), Harbinger (Columbia, South Carolina), Eastown Printing in Grand Rapids, Michigan (where the IWW negotiated a contract in 1978),[72]: 17 and La Presse Populaire (Montreal). This close affiliation with radical publishers and printing houses sometimes led to legal difficulties for the union, such as when La Presse Populaire was shut down in 1970 by provincial police for publishing pro-FLQ materials, which were banned at the time under an official censorship law. Also in 1970, the San Diego, California, "street journal" El Barrio became an official IWW shop. In 1971 its office was attacked by an organization calling itself the Minutemen, and IWW member Ricardo Gonzalves was indicted for criminal syndicalism along with two members of the Brown Berets.[13]

Return to workplace campaigns

[edit]

Invigorated by the arrival of enthusiastic new members, the IWW began a wave of organizing drives. These largely took a regional form and they, as well as the union's overall membership, concentrated in Portland, Chicago, Ann Arbor, and throughout the state of California, which when combined accounted for over half of union drives from 1970 to 1979. In Portland, Oregon, the IWW led campaigns at Winter Products (a brass plating plant) in 1972, at a local Winchell's Donuts (where a strike was waged and lost), at the Albina Day Care (where key union demands were won, including the firing of the director of the day care), of healthcare workers at West Side School and the Portland Medical Center, and of agricultural workers in 1974. The latter effort led to the opening of an IWW union hall in Portland to compete with extortionate hiring halls and day labor agencies. Organizing efforts led to a growth in membership, but repeated loss of strikes and organizing campaigns anticipated the decline of the Portland branch after the mid-1970s, a stagnancy period lasting until the 1990s.[72]: 15

In California, union activities were based in Santa Cruz, where in 1977 the IWW engaged in one of its most ambitious campaigns of the 1970s: an attempt in 1977 to organize 3,000 workers hired under the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) in Santa Cruz County. The campaign led to pay raises, the implementation of a grievance procedure, and medical and dental coverage, but the union failed to maintain its foothold, and in 1982 the CETA program was replaced by the Job Training Partnership Act.[72]: 15–16 The IWW won some lasting victories in Santa Cruz, such as campaigns at the Janus Alcohol Recovery Center, the Santa Cruz Law Center, Project Hope, and the Santa Cruz Community Switchboard.[72]: 16

Elsewhere in California, the IWW was active in Long Beach in 1972, where it organized workers at International Wood Products and Park International Corporation (a manufacturer of plastic swimming pool filters) and went on strike after the firing of one worker for union-related activities.[73] Finally, in San Francisco, the IWW ran campaigns for radio station and food service workers.[72]: 15–16

In Chicago, the IWW was an early opponent of so-called urban renewal programs and supported the creation of the "Chicago People's Park" in 1969. The Chicago branch also ran citywide campaigns for healthcare, food service, entertainment, construction, and metal workers, and its success with the latter led to an attempt to revive the national Metal and Machinery Workers Industrial Union, which twenty years earlier had been a major component of the union. Metalworker organizing mostly ended in 1978 after a failed strike at Mid-American Metal in Virden, Illinois. The IWW also became one of the first unions to try to organize fast food workers, with an organizing campaign at a local McDonald's in 1973.[72]: 16

The IWW also built on its existing presence in Ann Arbor, which had existed since student organizing began at the University of Michigan, to launch an organizing campaign at the University Cellar, a college bookstore. The union won National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) certification there in 1979 following a strike, and the store became a strong job shop for the union until it was closed in 1986. The union launched a similar campaign at another local bookstore, Charing Cross Books, but was unable to maintain its foothold there despite reaching a settlement with management.[72]: 17

In the late 1970s, the IWW came to regional prominence in entertainment industry organizing, with an Entertainment Workers Organizing Committee being founded in Chicago in 1976, followed by campaigns organizing musicians in Cleveland in 1977 and Ann Arbor in 1978. The Chicago committee published a model contract which was distributed to musicians in the hopes of raising industry standards, as well as maintaining an active phone line for booking information. IWW musicians such as Utah Phillips, Faith Petric, Bob Bovee, and Jim Ringer also toured and promoted the union,[72]: 17 and in 1987 an anthology album, Rebel Voices, was released.

Other IWW organizing campaigns of the 1970s included a ShopRite supermarket in Milwaukee, at Coronet Foods in Wheeling, West Virginia, chemical and fast food workers (including KFC and Roy Rogers) in State College, Pennsylvania, and hospital workers in Boston, all in 1973; shipyards in Houston, Texas, and restaurant workers in Pittsburgh in 1974; unsuccessful campaigns at the Prospect Nursing Home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and a Pizza Hut in Arkadelphia, Arkansas, in 1975; and a construction workers organizing drive in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 1978.[72]: 18

1990s

[edit]In 1996, the IWW launched an organizing drive against Borders Books in Philadelphia. In March, the union lost an NLRB certification vote by a narrow margin but continued to organize. In June, IWW member Miriam Fried was fired on trumped-up charges and a national boycott of Borders was launched in response. IWW members picketed at Borders stores nationwide, including Ann Arbor, Michigan; Washington, D.C.; San Francisco, California; Miami, Florida; Chicago, Illinois; Palo Alto, California; Portland, Oregon; Portland, Maine; Boston, Massachusetts; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Albany, New York; Richmond, Virginia; St. Louis, Missouri; Los Angeles, California; and other cities. This was followed up with a National Day of Action in 1997, where Borders stores were again picketed nationwide, and a second organizing campaign in London, England.[74]

Also in 1996, the IWW began organizing at Wherehouse Music in El Cerrito, California. The campaign continued until 1997, when management fired two organizers and laid off over half the employees, as well as reducing the hours of known union members. This directly affected the NLRB certification vote which followed, where the IWW lost over 2:1.[74]

In 1998, the IWW chartered a San Francisco branch of the Marine Transport Workers Industrial Union (MTWIU), which trained hundreds of waterfront workers in health and safety techniques and attempted to institutionalize these safety practices on the San Francisco waterfront.[75]

2000–present

[edit]In 2004, an IWW union was organized in a New York City Starbucks. In 2006, the IWW continued efforts at Starbucks by organizing several Chicago area shops.[78][79]

In New York City, the IWW has organized immigrant foodstuffs workers since 2005. That summer, workers from Handyfat Trading joined the IWW, and were soon followed by workers from four more warehouses.[80]

The Wobblies are back. Many young radicals find the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) the most congenial available platform on which to stand in trying to change the world.

In May 2007, the NYC warehouse workers came together with the Starbucks Workers Union to form The Food and Allied Workers Union IU 460/640. In the summer of 2007, the IWW organized workers at two new warehouses: Flaum Appetizing, a Kosher food distributor, and Wild Edibles, a seafood company. Over the course of 2007–08, workers at both shops were illegally terminated for their union activity. In 2008, the workers at Wild Edibles actively fought to get their jobs back and to secure overtime pay owed to them by the boss. In a workplace justice campaign called Focus on the Food Chain, carried out jointly with Brandworkers International, the IWW workers won settlements against employers including Pur Pac, Flaum Appetizing and Wild Edibles.[82][83][84][85]

The Portland, Oregon General Membership Branch is one of the largest and most active branches of the IWW. The branch holds three contracts currently, two with Janus Youth Programs and one with Portland Women's Crisis Line.[86] There has been some debate within the branch about whether or not union contracts such as this are desirable in the long run, with some members favoring solidarity unionism as opposed to contract unionism and some members believing there is room for both strategies for organizing. The branch has successfully supported workers wrongfully fired from several different workplaces in the last two years. Due to picketing by Wobblies, these workers have received significant compensation from their former employers. Branch membership has been increasing, as has shop organizing. As of 2005, the 100th anniversary of its founding, the IWW had around 5,000 members, compared to 13 million members in the AFL-CIO.[87]

2011 Wisconsin general strike

[edit]In early 2011, Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker announced a budget bill which the IWW held would effectively outlaw unions for state or municipal workers. In response, there was an emergency meeting of the Midwestern IWW member organizations. IWW members presented a proposal at a meeting of South-Central Federation of Labor (SCFL) which endorsed a general strike and create an ad hoc Committee to instruct affiliated locals in preparations for the general strike. The IWW proposal passed nearly unanimously. The Madison branch made an international appeal translating various materials concerning the strike into Arabic, French, Spanish, Italian and Portuguese. An appeal was made to European unions (CNT – Spain, CGT – Spain and CGT – France) to send organizers to Madison who could present their experience of general strikes at union meetings and help organize the strike in other ways. The CNT (France) sent letters of solidarity to the IWW. This was considered the largest and most successful intervention in a working-class struggle that the IWW has undertaken since the 1930s.[88] In the aftermath, the strike was said by some to be "the general strike that didn't happen" because eventually ongoing efforts at industrial action were "completely overwhelmed by the recall effort" against the governor during the crisis.[89]

Late 2010s

[edit]In the mid-2010s, Wobblies in the United States were focused on campaigns to organize the multinational coffeehouse chain Starbucks, the franchised sandwich fast food restaurant chain Jimmy John's, and the multinational supermarket chain Whole Foods Market. The union had about 3,000 members.[90] The IWW moved its headquarters to 2036 West Montrose, Chicago, in 2012.[91]

The IWW waged an organizing campaign at Chicago-Lake Liquors in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 2013. The store, which advertises itself as the highest-volume liquor store in Minnesota, had a wage cap of $10.50 per hour, but in the face of IWW demands for the wage cap to be lifted, store management fired five organizers. On April 6, the Twin Cities branch of the union responded with a picket around the store informing customers of the situation. This was followed by a second picket on May 4, a day which customarily had heavy business at the store. The union claimed to have made "what should have been an extremely busy Saturday into a quiet afternoon inside the store".[92] After several months, the National Labor Relations Board announced that it found merit in the union's unfair dismissal complaint.[93] As a result, the union and store management agreed to a $32,000 settlement as a form of compensation to the fired workers and the campaign officially ended.

Workers at the Paulo Freire Social Justice Charter School in Holyoke, Massachusetts were organized with the IWW in 2015, hoping to address the "authoritarian leadership" of the school administration and perceived racial bias in hiring.[94]

On September 14, 2015, after a year-long organizing campaign, workers at Sound Stage Production in North Haven Connecticut declared their membership in the IWW.[95]

The IWW announced the Burgerville Workers Union (BVWU) in April 2016, which focuses on workers at the Oregon regional fast food chain, Burgerville. A subsidiary of the IWW, the BVWU went public on April 26 at a rally of workers and supporters outside a Portland, Oregon Burgerville location. Upon going public, the BVWU was endorsed by a number of local Oregon community organizations, including union locals, the Portland Solidarity Network, and food and racial justice organizations.[96] It was also endorsed by then-Democratic presidential candidate Senator Bernie Sanders. The union received pushback with a letter from Burgerville's CEO, Jeff Harvey, being distributed to workers discouraging them from joining the union.[97] In June 2017, Burgerville paid a settlement of $10,000 after an investigation by the Oregon Bureau of Labor and Industries, which found that the company had violated state-mandated break periods for workers.[98] In April and May 2018 the IWW won NLRB elections in 2 Burgerville Locations.

In August 2016, workers at Ellen's Stardust Diner in Manhattan formed Stardust Family United (SFU)[99] under the IWW, driven by the firing of thirty employees, as well as an unpopular new scheduling system.[100] After going public, the union accused Stardust management of retaliatory firings and posting anti-union materials in the restaurant.[101]

On September 9, 2016, the 45th anniversary of the Attica Prison Riots, 900 incarcerated workers organized by the IWW and many other prisoners participated in the 9/9 National Prison Strike declared by the IWW's Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee.[102] Supported by a number of anti-incarceration and prisoners' organizations such as the Free Alabama Movement, the strike focused on the poor conditions in many American prisons and the low rates of prisoner pay for maintaining prisons and engaging in commercial production of goods for third-party companies.[103] The strike affected an estimated twenty prisons in eleven states and was strongest at the William C. Holman Correctional Facility in Alabama. Estimates of the number of inmates affected range from 20,000, to 50,000, to as high as 72,000, with David Fathi of the ACLU National Prison Project judging it to be the "largest prisoner strike in recent memory".[104][105][106] Initial media coverage was slow, with strike organizers complaining of a "mainstream-media blackout", which could be attributed to the difficulty in communicating with prisoners, as many prisons went on lockdown either in response to prisoner strike activity or in anticipation of it.[102]

COVID-19 pandemic

[edit]

The IWW also organized workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. In May 2020 the IWW established the Voodoo Doughnut Workers Union (DWU) in Portland. The newly formed union delivered a letter to management announcing the formation of a union and demanding higher wages, safety improvements and severance packages for employees laid off because of the coronavirus and Oregon's ongoing "shelter-in-place" order.[107] In February 2021, after months of organizing, DWU workers officially filed for a union certification election with the National Labor Relations Board.[108]

The IWW also publicly announced the Second Staff (2S) workers' union in May 2020 at the Faison school, a private school serving students on the autism spectrum in Richmond, Virginia, in response to what the union called a "reckless endangerment of staff and students" in trying to force the school to open too soon.[109] March 2021 saw a rash of organizing with the IWW. On March 9, workers at Moe's Books, an independent used bookstore in Berkeley, California, announced that they received voluntary recognition from Moe's Books management, officially unionizing with the IWW.[110]

Shortly after, on March 13, the IWW announced that it was organizing workers at the Socialist Rifle Association (SRA).[111] The union was voluntarily recognized by the SRA the following day. Two days later, on March 16, staff at the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition (OVEC) announced their intent to unionize with the IWW, and requested voluntary recognition from management. In organizing, the OVEC workers seek to gain "a standardized pay scale, an equitable discipline policy, and the right to union representation at any meeting wherein matters affecting staff pay, hours, benefits, advancement, or layoffs may be discussed or voted on".[112]

The IWW is the first union in the United States to ratify a union contract for fast food workers. Five Oregon locations of Burgerville are unionized,[113] as well as one location of Voodoo Doughnut in downtown Portland.[114]

Australia

[edit]Australia encountered the IWW tradition early. In part, this was due to the local De Leonist Socialist Labor Party following the industrial turn of the US SLP. The SLP formed an IWW Club in Sydney in October 1907. Members of other socialist groups also joined it, and the relationship with the SLP soon proved to be a problem. The 1908 split between the Chicago and Detroit factions in the United States was echoed by internal unrest in the Australian IWW from late 1908, resulting in the formation of a pro-Chicago local in Adelaide in May 1911 and another in Sydney six months later. By mid-1913 the "Chicago" IWW was flourishing and the SLP-associated pro-Detroit IWW Club in decline.[115] In 1916 the "Detroit" IWW in Australia followed the lead of the US body and renamed itself the Workers' International Industrial Union.[116]

The IWW opposed the First World War from 1914 onward and in many ways fought against Australian conscription.[117] A narrow majority of Australians voted against conscription in a very bitter hard-fought referendum in October 1916, and then again in December 1917, Australia being the only belligerent in World War One without conscription. In very significant part this was due to the agitation of the IWW, a group which never had as many as 500 members in Australia at its peak. The IWW founded the Anti-Conscription League (ACL) in which members worked with the broader labor and peace movement, and also carried on an aggressive propaganda campaign in its own name; leading to the imprisonment of Tom Barker (1887–1970) the editor of the IWW paper Direct Action, sentenced to twelve months in March 1916. A series of arson attacks on commercial properties in Sydney was widely attributed to the IWW campaign to have Tom Barker released. He was released in August 1916, but twelve mostly prominent IWW activists, the so-called Sydney Twelve were arrested in NSW in September 1916 for arson and other offenses. Their trial and eventual imprisonment became a cause célèbre of the Australian labor movement, which saw no convincing evidence of their involvement. A number of other scandals were associated with the IWW; a five-pound note forgery scandal, the so-called Tottenham tragedy in which the murder of a police officer was blamed on the IWW, and above all it was blamed for the defeat of the October 1916 conscription referendum. In December 1916, the Commonwealth government led by Labour Party renegade Billy Hughes declared the IWW an illegal organization under the Unlawful Associations Act. Eighty six members immediately defied the law and were sentenced to six months imprisonment. Direct Action was suppressed, its circulation was at its peak of something over 12,000.[118] During the war over 100 members Australia-wide were sentenced to imprisonment on political charges,[119] including the veteran activist Monty Miller.

By the early 1930s, most Australian IWW branches had dispersed as the Communist Party grew in influence.[120]

The Australian IWW has grown since the 1940s, but have been unsuccessful in securing union representation.[121] As an extreme example of the integration of ex-IWW militants into the mainstream labor movement one might instance the career of Donald Grant, one of the Sydney Twelve sentenced to fifteen years imprisonment for conspiracy to commit arson and other crimes. Released from prison in August 1920, he soon broke with the IWW over its antipolitical stand, standing for the NSW Parliament for the Industrial Socialist Labour Party unsuccessfully in 1922 and then in 1925 for the mainstream Australian Labor Party (ALP) also unsuccessfully. This reconciliation with the ALP and the electoral system did not prevent him being imprisoned again in 1927 for street demonstrations supporting Sacco and Vanzetti. He eventually represented the ALP in the NSW Legislative Council in 1931–1940 and the Australian Senate 1943–1956.[122]

"Bump Me Into Parliament"[123] is the most notable Australian IWW song, and is still current. It was written by ship's fireman William "Bill" Casey, later Secretary of the Seaman's Union in Queensland.[118]

New Zealand

[edit]Australian influence was strong in early 20th century left-wing groups, and several founders of the New Zealand Labour Party (e.g. Bob Semple) were from Australia. The trans-Tasman interchange was two-way, particularly for miners. Several Tasmanian Labour "groupings" in the 1890s cited their earlier New Zealand experience of activism e.g. later premier Robert Cosgrove, and also Chris Watson from New South Wales.[124]

"Wobbly" activists in New Zealand pre-WWI were John Benjamin King and H. M. Fitzgerald (an adherent of the De Leon school) from Canada. Another was Robert Rivers La Monte from America, who was (briefly) an organizer for the New Zealand Socialist Party (as was Fitzgerald). IWW strongholds were Auckland "a city with the demographic characteristics of a frontier town"; Wellington where a branch survived briefly and in mining towns, on the wharves and among laborers.[125]

Canada

[edit]

The IWW was active in Canada from a very early point in the organization's history, especially in Western Canada, primarily in British Columbia. The union was active in organizing large swaths of the lumber and mining industry along the coast, in the Interior of British Columbia, and Vancouver Island. Joe Hill wrote the song "Where the Fraser River Flows" during this period when the IWW was organizing in British Columbia. Some members of the IWW had relatively close links with the Socialist Party of Canada.[126] Canadians who went to Australia and New Zealand before WWI included John Benjamin King and H. M. Fitzgerald (an adherent of the De Leon school).[125]

The IWW was banned as a subversive organization in Canada during the First World War (and partially replaced by the One Big Union). After being unbanned after the war, the IWW reached a post-WWI high of 5600 Canadian members in 1923.[127] The union entered a short "golden age" in Canada with an official Canadian Administration located at the Finnish Labour Temple in Port Arthur (now Thunder Bay, Ontario) and a strong base among immigrant laborers in Northern Ontario and Manitoba, especially Finns, which included harvest workers, lumberjacks, and miners. During this period, the IWW competed for members with a number of other radical and socialist organizations such as the Finnish Organization of Canada (FOC), with the IWW's Industrialisti newspaper competing with the FOC's Vapaus for attention and readership. During this period. Membership slowly decreased during the 1920s and 30s despite continued organizing and strike activity as the IWW lost ground to the One Big Union and Communist Party-controlled organizations such as the Workers' Unity League (WUL). Despite this competition, the IWW and WUL cooperated during strikes, such as at the Abitibi Pulp & Paper Company near Sault Ste. Marie in 1933, where the Finnish workers in the IWW and WUL faced discrimination and violence from the Anglo citizens of the town. The IWW also successfully unionized Ritchie's Dairy in Toronto and formed a fishery workers' branch in MacDiarmid (now Greenstone, Ontario).[128]

In 1936, the IWW in Canada supported the Spanish Revolution and recruited for the militia of the anarcho-syndicalist Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT), in direct conflict with Communist Party recruiters for the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion. The disagreement caused violent clashes at recruitment rallies in Northern Ontario. Several Canadian IWW members were killed in the Spanish Civil War and the CNT's ensuing defeat at the hands of both Fascist and Republican forces.[128]

In 2009, after Starbucks established policies that meant demotions and wage cuts for some workers, IWW branches in Montreal and Sherbrooke helped found the Starbucks Workers' Union (STTS), which made a breakthrough in Quebec City at an establishment in Sainte-Foy.[129] Leaders Simon Gosselin, Dominic Dupont and Andrew Fletcher were harassed in the months following unionization, and union efforts were defeated by law firm Heenan Blaike in a series of hearings before Quebec Labor Relations Board.[130]

Today the IWW is active in Canada, with branches in Vancouver, Vancouver Island, Edmonton, Winnipeg, Ottawa/Outaouais, Toronto, Windsor, Sherbrooke, Québec City and Montréal.[131] In August 2009, Canadian members voted to ratify the constitution of the Canadian Regional Organizing Committee (CanROC) to improve inter-branch coordination and communication. Affiliated branches are Winnipeg, Ottawa-Outaouais, Toronto, Windsor, Sherbrooke, Montréal, and Québec City. Each branch elects a representative to make decisions on the Canadian board. There were originally three officers, the Secretary-Treasurer, Organizing Department Liaison, and Editor of the Canadian Organizing Bulletin.[132] In 2016, CanROC members voted to split the Secretary-Treasurer role into separate Regional Secretary and Regional Treasurer positions.

There are currently five job shops in Canada: Libra Knowledge and Information Services Co-op in Toronto, ParIT Workers Cooperative in Winnipeg, the Windsor Button Collective, the Ottawa Panhandlers' Union, and the Street Labourers of Windsor (SLOW). The Ottawa Panhandlers' Union continues a tradition in the IWW of expanding the definition of worker. The union members include anyone who makes their living in the street, including buskers, street vendors, the homeless, scrappers, and panhandlers. In the summer of 2004, the Union led a strike by the homeless (the Homeless Action Strike) in Ottawa. The strike resulted in the city agreeing to fund a newspaper created and sold by the homeless on the street. On May 1, 2006, the Union took over the Elgin Street Police Station for a day. A similar IWW organization, the Street Labourers of Windsor (SLOW), has garnered local,[133] provincial,[134] and national[135] news coverage for its organizing efforts in 2015.

Europe

[edit]Germany, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Austria

[edit]The IWW started to organize in Germany following the First World War. Fritz Wolffheim played a significant role in establishing the IWW in Hamburg. A German Language Membership Regional Organizing Committee (GLAMROC) was founded in December 2006 in Cologne. It encompasses the German-language area of Germany, Luxembourg, Austria, and Switzerland with branches or contacts in 16 cities.[136]

Great Britain and Ireland

[edit]The regional body of the union in the United Kingdom and Ireland is the Wales, Ireland, Scotland, England Regional Administration (WISERA). Formerly known as the Britain and Ireland Regional Administration (BIRA), its name was changed as a result of a referendum vote by WISERA members.[137]

The IWW was present, to varying extents, in many of the struggles of the early decades of the 20th century, including the UK general strike of 1926 and the dockers' strike of 1947. During the Spanish Civil War, a Wobbly from Neath, who had been active in Mexico, trained volunteers in preparation for the journey to Spain, where they joined the International Brigades to fight against Franco.[23]

Overall, membership has increased rapidly; in 2014, the union reported a total UK membership of 750,[138] which increased to 1000 by April 2015.[139]

Also in 2007, IWW branches in Glasgow and Dumfries were a key driving force in a successful campaign to prevent the closure of one of Glasgow University's campuses (The Crichton) in Dumfries.[140]

The Edinburgh General Membership Branch of the IWW along with other branches of the IWW's Scottish section voted in 2014 to become a signatory to the "From Yes to Action Statement" produced by the Autonomous Centre of Edinburgh. In 2015, along with similar groups such as the Edinburgh Coalition Against Poverty and Edinburgh Anarchist Federation, they joined the Scottish Action Against Austerity network.[141]

In 2016, WISERA promoted a campaign targeting couriers working for companies such as Deliveroo.[142]

WISERA currently has campaigns organising TEFL teachers, brewery workers and escape room workers.[143][144][145]

Iceland and Greece

[edit]An Iceland Regional Organizing Committee (IceROC)[146] was chartered in 2015. The union has become a trailblazer in supporting sex workers in Iceland, who lack access to services which do not automatically treat them as victims of abuse.[147]

Also in 2015, a Greek Regional Organizing Committee (GreROC) was chartered. In July of that year, it released a statement condemning the Greek government's response to the results of the 2015 Greek bailout referendum, saying that "despite the Left tone of dignity that the Left governmental administrators use, this is a one-way blackmail. We need a radical change of shift, not in words but in action."[148]

Folk music and protest songs

[edit]

One Wobbly characteristic since their inception has been a penchant for song. To counteract management sending in the Salvation Army band to cover up the Wobbly speakers, Joe Hill wrote parodies of Christian hymns so that union members could sing along with the Salvation Army band, but with their own purposes. For example, "In the Sweet By and By" became "There'll Be Pie in the Sky When You Die (That's a Lie)". From that start in exigency, Wobbly song writing became common because they "articulated the frustrations, hostilities, and humor of the homeless and the dispossessed."[149]

Literature

[edit]Karl Marlantes's 2019 novel Deep River explores labor issues in the early 1900s in the US and the consequences for an immigrant Finnish family. The book focuses on a female family member who becomes an organizer for the IWW in the dangerous logging industry. Both pro- and anti-labor viewpoints are examined, with special attention given to IWW strikes and the backlash against the labor movement during World War I.[150]

Lingo

[edit]Wobbly lingo is a collection of technical language, jargon, and historic slang used by the Wobblies, for more than a century. Many Wobbly terms derive from or are coextensive with hobo expressions used through the 1940s.[151][152] The origin of the name "Wobbly" itself is uncertain.[5][153][154] For several decades, many hobos in the United States were members of, or were sympathetic to, the IWW. Because of this, some of the terms describe the life of a hobo such as "riding the rails", living in "jungles", dodging the "bulls". The IWW's efforts to organize all trades allowed the lingo to expand to include terms relating to mining camps, timber work, and farming.[155][156]

Some words and phrases believed to have originated within Wobbly lingo have gained cultural significance outside of the IWW. For example, from Joe Hill's song "The Preacher and the Slave", the expression pie in the sky has passed into common usage, referring to a "preposterously optimistic goal".[157]

Notable members

[edit]Former lieutenant governor of Colorado David C. Coates was a labor militant, and was present at the founding convention,[54]: 242–278 although it is unknown if he became a member. It has long been rumored, but not proven, that baseball legend Honus Wagner was also a Wobbly. Senator Joseph McCarthy accused Edward R. Murrow of having been an IWW member, which Murrow denied.[158]

See also

[edit]- 1933 Yakima Valley strike

- Bérmunkás

- Centralia massacre

- Eugene V. Debs

- History of the Industrial Workers of the World

- Industrial democracy

- Industrial Revolution

- Industrial Workers of the World (Chile)

- Industrial Workers of the World (South Africa)

- Industrial Workers of the World philosophy and tactics

- Kuzbass Autonomous Industrial Colony

- Labor disputes led by the Industrial Workers of the World

- Labor federation competition in the United States

- List of Industrial Workers of the World unions

- Mechanization

- One Big Union (concept)

- Redwood Summer

- San Diego free speech fight

- Seattle General Strike

- Silent agitators

- Solidarity unionism

- Syndicalism

- Women in labor unions

Explanatory notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "IWW Chronology (1904–1911)". Industrial Workers of the World. Archived from the original on March 25, 2020. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ "Minutes of the IWW Founding Convention". Industrial Workers of the World. Archived from the original on April 13, 2020. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ "070-232 (LM2) 06/30/2021". Office of Labor-Management Standards. U.S. Department of Labor. Archived from the original on October 1, 2024. Retrieved December 31, 2021. This is the IWW's "Form LM-2 Labor Organization Annual Report", covering the period from July 1, 2020 – June 30, 2021.

- ^ "Form AR21 Trade Union and Labour Relations (consolidation) Act 1992" (PDF). UK Government Certification Office. 2023. Retrieved May 13, 2025.

- ^ a b "What is the Origin of the Term Wobbly?". Industrial Workers of the World. Archived from the original on May 6, 2019. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Caro-Morente, Jaime. "The political culture of the IWW in its first 20 years". Industrial Worker. Vol. 114, no. 1780/3 (Summer 2017 ed.). Archived from the original on June 19, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Chester, Eric Thomas (2014). The Wobblies in Their Heyday: The Rise and Destruction of the Industrial Workers of the World during the World War I Era. ABC-CLIO. p. xii. ISBN 9781440833021. Archived from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ "IWW membership peaked at around 100,000 in the mid-1910s. This number is, however, somewhat misleading in regard to overall union reach and activity. Between 1905 and 1915, for example, the IWW’s turnover rate in membership was an astonishing 133 percent. It is, therefore, entirely possible that more than one million Americans aligned with the IWW at various times. That said, the IWW never claimed more than 5 percent of the entire American working population at any one time". Johnathan Foster (2017). "International Workers of the World"; pp. 260-262 in Jeffrey A. Johnson (ed.). Reforming America: A Thematic Encyclopedia and Document Collection of The Progressive Era. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, LLC, ISBN 978-1-4408-3720-3

- ^ a b c d e Brissenden, Paul Frederick (1920). The I.W.W.: A Study of American Syndicalism. Vol. 83 (2nd ed.). Columbia University.

- ^ a b c Saros, Daniel E. (2009). Labor, Industry, and Regulation During the Progressive Era. Routledge. ISBN 9781135842338. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Minister of Justice (September 24, 1918). "Regulations declaring organizations, associations, societies etc as illegal: I. W. W. [Industrial Workers of the World] Bolshevik Social Democrats etc – Item: 1918-2384". Government of Canada. Archived from the original on August 10, 2022. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- ^ Renshaw, Patrick (1967). The Wobblies: The Story of the IWW and Syndicalism in the United States. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. p. 286. ISBN 9781566632737. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ a b c "IWW Chronology (1946–1971)". IWW.org. Industrial Workers of the World. Archived from the original on December 25, 2016. Retrieved December 24, 2016.

- ^ "IWW Organizing in the 1970s". IWW.org. Industrial Workers of the World. Archived from the original on May 2, 2023. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ a b "Preamble to the IWW Constitution". Industrial Workers of the World. Archived from the original on November 24, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Parker, Martin; Fournier, Valérie; Reedy, Patrick (August 2007). The Dictionary of Alternatives: Utopianism and Organization. Zed Books. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-84277-333-8. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ "(1) I am a student, a retired worker, and/or I am unemployed; can I still be an IWW member?". Industrial Workers of the World. Archived from the original on October 15, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ "(2) I am a member of another union; can I still I join the IWW?". Industrial Workers of the World. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Thompson, Fred (1955). The I. W. W., its first fifty years, 1905-1955;the history of an effort to organize the working class. Chicago: Industrial Workers of the World. p. 6. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ "Industrial Workers of the World - Labour Organization". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Archived from the original on August 10, 2022. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Strang, Dean A. (2019). Keep the Wretches in Order: America's Biggest Mass Trial, the Rise of the Justice Department, and the Fall of the IWW. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 12. ISBN 0299323307.

- ^ Kostiainen, Auvo. "Finnish-American Workmen's Associations". Genealogia.fi. Archived from the original on February 23, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ a b Cole, Peter; Struthers, David; Zimmer, Kenyon, eds. (2017). "P. J. Welinder and "American Syndicalism". Wobblies of the World: A Global History of the IWW. Pluto Press. p. 262. ISBN 978-0745399591. Archived from the original on February 23, 2018. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ^ Keller, Helen; Davis, John (2003). Helen Keller: Rebel Lives. Ocean Press. p. 57. ISBN 9781876175603.

- ^ "Short history of Pressed Steel Car Company". NEIU.edu. Archived from the original on August 28, 2009. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Foner, Philip S. (1997). History of the Labor Movement in the United States Vol. 4: The Industrial Workers of the World 1905–1917. International Publishers. p. 147. ISBN 978-0717803965.

- ^ Hermida, Arianne. "IWW Local Unions 1906-1917 (maps)". IWW History Project. UW Departments. Archived from the original on June 12, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Ettlling, Alex; McIntyre, Iain; Milliss, Ian; Milner, Lisa; Towart, Neale (February 14, 2022). "Lines of Resistance: What can the Old Left offer today's creatives?". The Commons Social Change Library. Archived from the original on March 1, 2023. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ^ Anderson, Colin M. (1999). "The Industrial Workers of the World in the Seattle General Strike". depts.washington.edu. Archived from the original on October 15, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Gregory, James. "Faces of the IWW: The Men Arrested after the Everett Massacre". depts.washington.edu. Archived from the original on October 15, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Weber, Devra Ann (2016). "Mexican Workers in the IWW and the Partido Liberal Mexicano (PLM)". depts.washington.edu. Archived from the original on October 15, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Cole, Peter (2015). "Local 8: Philadelphia's Interracial Longshore Union". depts.washington.edu. Archived from the original on August 10, 2022. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Elliott, Russell R. (1966). Nevada's Twentieth-Century Mining Boom: Tonopah, Goldfield, Ely. University of Nevada Press. ISBN 9780874171334.

- ^ "This fabric under which we have lived (editorial)". American Bar Association Journal. 54 (5): 474. May 1968. JSTOR 25724408.

- ^ Fink, Gary M. (1984). Biographical Dictionary of American Labor. Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313228650.

- ^ a b c d Dubofsky, Melvin (2000). McCartin, Joseph A. (ed.). We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252069055. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ "Disrupted by I.W.W." Los Angeles Times. June 22, 1914. Archived from the original on October 3, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ "Mine Federation in West Doomed by Faction's War". Chicago Daily Tribune. June 27, 1914. Archived from the original on October 3, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Official Proceedings of the Twentieth Annual Convention (Report). Western Federation of Miners. July 1912. pp. 283–284.

- ^ Acuña, Rodolfo F. (2007). Corridors of Migration: The Odyssey of Mexican Laborers, 1600–1933. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-8165-4329-8. Archived from the original on October 1, 2024. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ^ Benton-Cohen, Katherine (2009). Borderline Americans: Racial Division and Labor War in the Arizona Borderlands. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-674-05355-7.

- ^ Mellinger, Philip J. (1995). Race and Labor in Western Copper: The Fight for Equality, 1896–1918. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-8165-4772-2.

- ^ Capace, Nancy (January 1, 2000). Encyclopedia of Montana. Somerset Publishers. p. 156. ISBN 9780403096046. Archived from the original on August 10, 2022. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Mayo, Katherine (1917). Justice to All: the Story of the Pennsylvania State Police. G.P. Putnam's Sons. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Chester, Eric Thomas (2014). The Wobblies in Their Heyday: The Rise and Destruction of the Industrial Workers of the World during the World War I Era. Praeger Publishers. pp. 29–53. ISBN 978-1440833014. Archived from the original on October 1, 2024. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ McGuckin, Henry E. (1987). Memoirs of a Wobbly. Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company. p. 70.

- ^ One Big Union. 1986.

- ^ Thompson, Fred W.; Murfin, Patrick (1976). The I.W.W.: Its First Seventy Years, 1905–1975. p. 100.

- ^ Greenhouse, Steven (August 26, 2011). "Examining a Labor Hero's Death". New York Times. Archived from the original on October 15, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Adler, William M. (2011). "11: Majesty of the Law". The Man Who Never Died: The Life, Times, and Legacy of Joe Hill, American Labor Icon. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

- ^ Humanities, National Endowment for the (November 6, 1916). "The Tacoma times., November 06, 1916, Image 1". The Tacoma Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 15, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2018. -- also reported 20 IWW and 20 Everett citizens were wounded

- ^ "Deputy Sheriff Jefferson F. Beard". Officer Down Memorial Page. Archived from the original on August 10, 2022. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

Although the exact circumstances are unknown, it is thought that both deputies were struck by friendly fire.

- ^ "080. Members of Everett Citizens' Committee Killed and Injured in Battle with I.W.W." Archived from the original on October 15, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ a b c Carlson, Peter (1984). Roughneck: The Life and Times of Big Bill Haywood. W. W. Norton and Company. ISBN 978-0393302080. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Schlossberg, Stephen I. (August 2, 2017). "The Role of the Union Lawyer". North Carolina Law Review: 650. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- ^ "I.W.W. Members Are Held Guilty". Tulsa Daily World. November 10, 1917. p. 2. Archived from the original on December 21, 2018. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- ^ "Modern Ku Klux Klan Comes into Being". Tulsa Daily World. November 10, 1917. p. 1. Archived from the original on December 21, 2018. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- ^ "Harlow's Weekly - A Journal of Comment & Current Events for Oklahoma". Harlow Publishing Company. November 14, 1917. p. 4. Archived from the original on December 21, 2018. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- ^ Paul, Brad A. (January 1, 1999). "Rebels of the New South : the Socialist Party in Dixie, 1892-1920". University of Massachusetts Amherst. pp. 171, 176, 189. Archived from the original on December 21, 2018. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- ^ "Wesley Everest, IWW Martyr". Pacific Northwest Quarterly. October 1986.

- ^ Sexton, Owen (November 13, 2023). "Centralia Tragedy: After decades-long fight, IWW gets plaque for union victims". The Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 1, 2024. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ^ Sexton, Owen (June 26, 2024). "IWW union members commemorate monument honoring Centralia Tragedy victims at George Washington Park". The Chronicle. Retrieved January 22, 2025.

- ^ Thompson, Fred. "They didn't suppress the Wobblies". libcom.org. Radical America (September–October 1967). Archived from the original on August 10, 2022. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- ^ Higbie, Frank Tobias (2003). Indispensable Outcasts: Hobo Workers and Community in the American Midwest, 1880-1930. University of Illinois Press. pp. 166, 280. ISBN 978-0-252-07098-3. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- ^ Beal, Fred Erwin (1937). Proletarian journey: New England, Gastonia, Moscow. New York: Hillman-Curl. pp. 283–284, 289–291. Archived from the original on August 10, 2022. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- ^ "The IWW and the failure of revolutionary syndicalism in the USA, part ii | International Review". en.internationalism.org. 2006. Archived from the original on January 22, 2022. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- ^ Tar, Duncan (2015). "The Reds and the Wobs: Radical Organization and Identity in the United States 1910-1930" (PDF). Michigan Journal of History. 7: 22–45. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 5, 2022. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- ^ Green, Gil (1990). Schultz, Bud; Schultz, Ruth (eds.). It Did Happen Here: Recollections of Political Repression in America. University of California Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-520-91068-3. Archived from the original on August 10, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Tyler, Robert L. (January 1967). Rebels of the woods: the I.W.W. in the Pacific Northwest. University of Oregon Books. p. 227. ISBN 9780870713880. Archived from the original on January 1, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ Lee, Frederic S.; Bekken, Jon (2009). Radical economics and labor: essays inspired by the IWW Centennial. Taylor & Francis US. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-415-77723-0. Archived from the original on January 1, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ "Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)". Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Cleveland: Case Western Reserve University. Archived from the original on June 5, 2016. Retrieved May 20, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Silvano, John, ed. (1999). Nothing in Common: An Oral History of IWW Strikes 1971–1992. Cedar Rapids, Iowa: Cedar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-892779-22-9. LCCN 99-65777.

- ^ Strike Support, Portland General Membership Branch, IWW, 1972

- ^ a b "IWW Chronology (1996–1997)". IWW.org. Industrial Workers of the World. Archived from the original on December 24, 2016. Retrieved December 24, 2016.

- ^ "IWW Chronology (1998–1999)". Industrial Workers of the World. Archived from the original on December 25, 2016. Retrieved December 24, 2016.

- ^ US Department of Labor, Office of Labor-Management Standards. File number 070-232. (Search)

- ^ "Industrial Workers of the World: annual returns". UK Certification Officer. 2013. Archived from the original on December 9, 2014.

- ^ Dawdy, Philip (December 7, 2005). "A Union Shop on Every Block". Seattle Weekly. Archived from the original on February 21, 2010. Retrieved September 24, 2006.

- ^ Agnos, Damon=Seattle Weekly (May 4, 2009). "Back to the Future: Starbucks vs. the Wobblies". Seattle Weekly. Archived from the original on February 21, 2010. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- ^ Esch, Caitlin (April 2007). "Wobblies organize Brooklyn warehouses". The Brooklyn Rail. Archived from the original on February 6, 2008.

- ^ Lynd, Staughton (December 6, 2014). "Wobblies Past and Present". Jacobin Magazine. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ Krauthamer, Diane (February 3, 2008). "Taming Wild Edibles". Industrial Workers of the World. Archived from the original on May 12, 2011.

- ^ Greenhouse, Steven (January 20, 2010). "Wild Edibles Settles With Workers' Group Pushing Boycott". New York Times. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved September 21, 2012.

- ^ Kapp, Trevor (August 19, 2011). "Immigrants win $470,000 settlement for wage fight from Pur Pac, major Chinese restaurant supplier". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved September 21, 2012.

- ^ Massey, Daniel (August 21, 2011). "Food industry: promise, problems". Crains New York. Archived from the original on April 4, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2012.

- ^ "PortlandIWW.org – About". Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ Moberg, David (July 19, 2005). "Culture: Power to the Pictures". In These Times Magazine.

- ^ "IWW General Strike 2011 – About". Archived from the original on March 23, 2016. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- ^ "The general strike that didn't happen: a report on the activity of the IWW in Wisconsin – Industrial Workers of the World". www.iww.org. Archived from the original on March 23, 2016. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- ^ DePillis, Lydia (March 5, 2015). "Why a D.C. bike shop is joining a radical socialist union". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on September 28, 2019. Retrieved October 12, 2021.