Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ajmaline

View on Wikipedia | |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Gilurytmal, Ritmos, Aritmina |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| ATC code | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.022.219 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C20H26N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 326.440 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

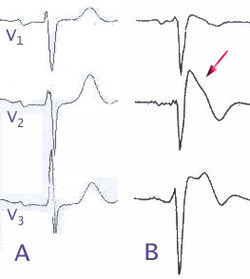

Ajmaline (also known by trade names Gilurytmal, Ritmos, and Aritmina) is an alkaloid that is classified as a 1-A antiarrhythmic agent. It is often used to induce arrhythmic contraction in patients suspected of having Brugada syndrome. Individuals suffering from Brugada syndrome will be more susceptible to the arrhythmogenic effects of the drug, and this can be observed on an electrocardiogram as an ST elevation.

The compound was first isolated by Salimuzzaman Siddiqui in 1931 [1] from the roots of Rauvolfia serpentina. He named it ajmaline, after Hakim Ajmal Khan, one of the most illustrious practitioners of Unani medicine in South Asia.[2] Ajmaline can be found in most species of the genus Rauvolfia as well as Catharanthus roseus.[3] In addition to Southeast Asia, Rauvolfia species have also been found in tropical regions of India, Africa, South America, and some oceanic islands. Other indole alkaloids found in Rauvolfia include reserpine, ajmalicine, serpentine, corynanthine, and yohimbine. While 86 alkaloids have been discovered throughout Rauvolfia vomitoria, ajmaline is mainly isolated from the stem bark and roots of the plant.[3]

Due to the low bioavailability of ajmaline, a semisynthetic propyl derivative called prajmaline (trade name Neo-gilurythmal) was developed that induces effects similar to those of its predecessor but which has better bioavailability and absorption.[4]

Biosynthesis

[edit]Ajmaline is widely dispersed among 25 plant genera, but is of significant concentration in the Apocynaceae family.[5] Ajmaline is a monoterpenoid indole alkaloid, composed of an indole from tryptophan and a terpenoid from iridoid glucoside secologanin. Secologanin is introduced from the triose phosphate/pyruvate pathway.[6] Tryptophan decarboxylase (TDC) remodels tryptophan into tryptamine. Strictosidine synthase (STR), uses a Pictet–Spengler reaction to form strictosidine from tryptamine and secologanin. Strictosidine is oxidized by P450-dependent sarpagan bridge enzymes (SBE); to make polyneuridine aldehyde. Of the sarpagan-type alkaloids, polyneuridine is a key entry into the ajmalan-type alkaloids.[7][6] Polyneuridine Aldehyde is methylated by polyneuridine aldehydeesterase (PNAE), to synthesize 16-epi-vellosimine, which is acetylated to vinorine by vinorine synthase (VS). Vinorine is oxidized by vinorine hydroxylase (VH) to make vomilenine. Vomilenine reductase (VR) conducts a reduction of vomilenine to 1,2-dihydrovomilenine, using the cofactor NADPH. 1,2-dihydrovomilenine, is reduced by 1,2-dihydrovomilenine reductase (DHVR) to 17-O-acetylnorajmaline, with the same cofactor as VR: NADPH. 17-O-acetylnorajmaline is deacetylated by acetylajmalan esterase (AAE), to form norajmaline. Finally, norajmaline methyl transferase (NAMT) methylates norajmaline resulting in our desired compound: ajmaline.[6]

Mechanism of action

[edit]

Ajmaline [8] was first discovered to lengthen the refractory period of the heart by blocking sodium ion channels,[3] but it has also been noted that it is also able to interfere with the hERG (human Ether-a-go-go-Related Gene) potassium ion channel.[9] In both cases, Ajmaline causes the action potential to become longer and ultimately leads to bradycardia. When ajmaline reversibly blocks hERG, repolarization occurs more slowly because it is harder for potassium to get out due to less unblocked channels, therefore making the RS interval longer. Ajmaline also prolongs the QR interval since it can also act as sodium channel blocker, therefore making it take longer for the membrane to depolarize in the first case. In both cases, ajmaline causes the action potential to become longer. Slower depolarization or repolarization results in a lengthened QT interval (the refractory period), and therefore makes it take more time for the membrane potential to get below the threshold level so the action potential can be re-fired. Even if another stimulus is present, action potential cannot occur again until after complete repolarization. Ajmaline causes action potentials to be prolonged, therefore slowing down firing of the conducting myocytes which ultimately slows the beating of the heart.

Diagnosis of Brugada syndrome

[edit]

Brugada syndrome is a genetic disease that can result in mutations in the sodium ion channel (gene SCN5A) of the myocytes in the heart.[10] Brugada syndrome can result in ventricular fibrillation and potentially death. It is a major cause of sudden unexpected cardiac death in young, otherwise healthy people.[11] While the characteristic patterns of Brugada syndrome on an electrocardiogram may be seen regularly, often the abnormal pattern is only seen spontaneously due to unknown triggers or after challenged by particular drugs. Ajmaline is used intravenously to test for Brugada syndrome since they both affect the sodium ion channel.[12] In an afflicted person who was induced with ajmaline, the electrocardiogram would show the characteristic pattern of the syndrome where the ST segment is abnormally elevated above the baseline. Due to complications that could arise with the ajmaline challenge, a specialized doctor should perform the administration in a specialized center capable of extracorporeal membrane oxygenator support.[13]

See also

[edit]- Salimuzzaman Siddiqui (1897–1994) Pakistani organic chemist

- Hellmuth Kleinsorge (1920–2001) German medical doctor

References

[edit]- ^ Siddiqui S, Siddiqui RH (1931). "Chemical examination of the roots of Rauwolfia serpentina Benth". J. Indian Chem. Soc. 8: 667–80.

- ^ Sandilvi AN (12 April 2003). "Salimuzzaman Siddiqui: pioneer of scientific research in Pakistan". Daily Dawn. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27.

- ^ a b c Roberts MF, Wink M (1998). Alkaloids: Biochemistry, Ecology, and Medical applications. Plenum Press.

- ^ Hinse C, Stöckigt J (July 2000). "The structure of the ring-opened N beta-propyl-ajmaline (Neo-Gilurytmal) at physiological pH is obviously responsible for its better absorption and bioavailability when compared with ajmaline (Gilurytmal)". Die Pharmazie. 55 (7): 531–532. PMID 10944783.

- ^ Namjoshi OA, Cook JM (2016). "Sarpagine and Related Alkaloids". The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology. Vol. 76. pp. 63–169. doi:10.1016/bs.alkal.2015.08.002. ISBN 9780128046821. PMC 4864735. PMID 26827883.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Wu F, Kerčmar P, Zhang C, Stöckigt J (2015). "Sarpagan-Ajmalan-Type Indoles: Biosynthesis, Structural Biology, and Chemo-Enzymatic Significance". The Alkaloids. Chemistry and Biology. 76: 1–61. doi:10.1016/bs.alkal.2015.10.001. PMID 26827882.

- ^ Turpin V, et al. (2020). "Biosynthetically Relevant Reactivity of Polyneuridine Aldehyde". European Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2020 (45): 6989–6991. doi:10.1002/ejoc.202000963. S2CID 225501365.

- ^ "Ajmaleen 54 | Unani Medicine for High blood Pressure | Ajmal.pk". Dawakhana Hakim Ajmal Khan. 14 June 2019. Retrieved 2019-08-09.

- ^ Kiesecker C, Zitron E, Lück S, Bloehs R, Scholz EP, Kathöfer S, et al. (December 2004). "Class Ia anti-arrhythmic drug ajmaline blocks HERG potassium channels: mode of action". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 370 (6): 423–435. doi:10.1007/s00210-004-0976-8. PMID 15599706. S2CID 22310415.

- ^ Hedley PL, Jørgensen P, Schlamowitz S, Moolman-Smook J, Kanters JK, Corfield VA, Christiansen M (September 2009). "The genetic basis of Brugada syndrome: a mutation update". Human Mutation. 30 (9): 1256–1266. doi:10.1002/humu.21066. PMID 19606473.

- ^ Kusumoto FM, Bailey KR, Chaouki AS, Deshmukh AJ, Gautam S, Kim RJ, et al. (September 2018). "Systematic Review for the 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society". Circulation. 138 (13): e392 – e414. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000550. PMID 29084732.

- ^ Rolf S, Bruns HJ, Wichter T, Kirchhof P, Ribbing M, Wasmer K, et al. (June 2003). "The ajmaline challenge in Brugada syndrome: diagnostic impact, safety, and recommended protocol". European Heart Journal. 24 (12): 1104–1112. doi:10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00195-7. PMID 12804924.

- ^ Ciconte G, Monasky MM, Vicedomini G, Borrelli V, Giannelli L, Pappone C (October 2019). "Unusual response to ajmaline test in Brugada syndrome patient leads to extracorporeal membrane oxygenator support". Europace. 21 (10): 1574. doi:10.1093/europace/euz139. PMID 31157372.