Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hair follicle

View on Wikipedia| Hair follicle | |

|---|---|

Hair follicle | |

A photograph of hair on a human arm emerging from follicles | |

| Details | |

| System | Integumentary system |

| Artery | Supratrochlear, supraorbital, superficial temporal, occipital |

| Vein | Superficial temporal, posterior auricular, occipital |

| Nerve | Supratrochlear, supraorbital, greater occipital, lesser occipital |

| Lymph | Occipital, mastoid |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | folliculus pili |

| MeSH | D018859 |

| TA98 | A16.0.00.023 |

| TA2 | 7064 |

| TH | H3.12.00.3.01034 |

| FMA | 70660 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The hair follicle is an organ found in mammalian skin.[1] It resides in the dermal layer of the skin and is made up of 20 different cell types, each with distinct functions. The hair follicle regulates hair growth via a complex interaction between hormones, neuropeptides, and immune cells.[1] This complex interaction induces the hair follicle to produce different types of hair as seen on different parts of the body. For example, terminal hairs grow on the scalp and lanugo hairs are seen covering the bodies of fetuses in the uterus and in some newborn babies.[1] The process of hair growth occurs in distinct sequential stages: anagen is the active growth phase, catagen is the regression of the hair follicle phase, telogen is the resting stage, exogen is the active shedding of hair phase and kenogen is the phase between the empty hair follicle and the growth of new hair.[1]

The function of hair in humans has long been a subject of interest and continues to be an important topic in society, developmental biology and medicine. Of all mammals, humans have the longest growth phase of scalp hair compared to hair growth on other parts of the body.[1] For centuries, humans have ascribed esthetics to scalp hair styling and dressing and it is often used to communicate social or cultural norms in societies. In addition to its role in defining human appearance, scalp hair also provides protection from UV sun rays and is an insulator against extremes of hot and cold temperatures.[1] Differences in the shape of the scalp hair follicle determine the observed ethnic differences in scalp hair appearance, length and texture.

There are many human diseases in which abnormalities in hair appearance, texture or growth are early signs of local disease of the hair follicle or systemic illness. Well known diseases of the hair follicle include alopecia[2] or hair loss, hirsutism or excess hair growth and lupus erythematosus.[3][2]

Structure

[edit]

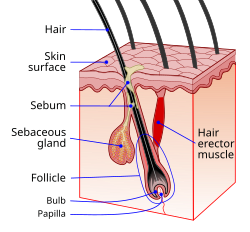

The position and distribution of hair follicles varies over the body. For example, the skin of the palms and soles does not have hair follicles whereas skin of the scalp, forearms, legs and genitalia has abundant hair follicles.[1] There are many structures that make up the hair follicle. Anatomically, the triad of hair follicle, sebaceous gland and arrector pili muscle make up the pilosebaceous unit.[1]

A hair follicle consists of :

- The papilla is a large structure at the base of the hair follicle.[4] The papilla is made up mainly of connective tissue and a capillary loop. Cell division in the papilla is either rare or non-existent.[contradictory]

- Around the papilla is the hair matrix.

- A root sheath composed of an external and internal root sheath. The external root sheath appears empty with cuboid cells when stained with H&E stain. The internal root sheath is composed of three layers, Henle's layer, Huxley's layer, and an internal cuticle that is continuous with the outermost layer of the hair fiber.

- The bulge is located in the outer root sheath at the insertion point of the arrector pili muscle. It houses several types of stem cells, which supply the entire hair follicle with new cells, and take part in healing the epidermis after a wound.[5][6] Stem cells express the marker LGR5+ in vivo.[7]

Other structures associated with the hair follicle include the cup in which the follicle grows known as the infundibulum,[8] the arrector pili muscles, the sebaceous glands, and the apocrine sweat glands. Hair follicle receptors sense the position of the hair.

Attached to the follicle is a tiny bundle of muscle fiber called the arrector pili. This muscle is responsible for causing the follicle lissis to become more perpendicular to the surface of the skin, and causing the follicle to protrude slightly above the surrounding skin (piloerection) and a pore encased with skin oil. This process results in goose bumps (or goose flesh).

Also attached to the follicle is a sebaceous gland, which produces the oily or waxy substance sebum. The higher the density of the hair, the more sebaceous glands that are found.

Variation

[edit]There are racial differences in several different hair characteristics. The differences in appearance and texture of hair are due to many factors: the position of the hair bulb relative to the hair follicle, size and shape of the dermal papilla, and the curvature of the hair follicle.[1] The scalp hair follicle in people of European descent is elliptical in shape and, therefore, produces straight or wavy hair, whereas the scalp hair follicle of people of African descent is more curvy, resulting in the growth of tightly curled hair.[1]

| Race | diameter

(micrometers) |

cross-sectional shape | appearance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blonde-haired white | 40–80 | elliptical | straight or wavy |

| Dark brown/black haired/red haired white | 50–90 | elliptical | straight or wavy |

| Black | 60–100 | elliptical and ribbon-like | curly |

| Asian | 80–100 | circular | straight |

| Animal | diameter

(micrometers) |

cross-sectional shape | appearance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chimpanzee | 101-113 | circular | straight |

| Orangutan | 140-170 | circular | straight |

| Buffalo | 110 | circular | straight |

Development

[edit]In utero, the epithelium and underlying mesenchyme interact to form hair follicles.[11][12]

Aging

[edit]A key aspect of hair loss with age is the aging of the hair follicle. Ordinarily, hair follicle renewal is maintained by the stem cells associated with each follicle. Aging of the hair follicle appears to be primed by a sustained cellular response to the DNA damage that accumulates in renewing stem cells during aging.[13] This damage response involves the proteolysis of type XVII collagen by neutrophil elastase in response to the DNA damage in the hair follicle stem cells. Proteolysis of collagen leads to elimination of the damaged cells and then to terminal hair follicle miniaturization.

Hair growth

[edit]Hair grows in cycles of various phases:[14] anagen is the growth phase; catagen is the involuting or regressing phase; and telogen, the resting or quiescent phase (names derived using the Greek prefixes ana-, kata-, and telos- meaning up, down, and end respectively). Each phase has several morphologically and histologically distinguishable sub-phases. Prior to the start of cycling is a phase of follicular morphogenesis (formation of the follicle). There is also a shedding phase, or exogen, that is independent of anagen and telogen in which one or several hairs that might arise from a single follicle exits. Normally up to 85% of the hair follicles are in anagen phase, while 10–14% are in telogen and 1–2% in catagen. The cycle's length varies on different parts of the body. For eyebrows, the cycle is completed in around 4 months, while it takes the scalp 3–4 years to finish; this is the reason eyebrow hair have a much shorter length limit compared to hair on the head. Growth cycles are controlled by a chemical signal like epidermal growth factor. DLX3 is a crucial regulator of hair follicle differentiation and cycling.[15][16]

Anagen phase

[edit]Anagen is the active growth phase of hair follicles[17] during which the root of the hair is dividing rapidly, adding to the hair shaft. During this phase the hair grows about 1 cm every 28 days. A hair pulled out in this phase will typically have the root sheath attached to it which appears as a clear gel coating the first few mm of the hair from its base; this may be misidentified as the follicle, the root or the sebaceous gland by non-health care professionals. Scalp hair stays in this active phase of growth for 2–7 years; this period is genetically determined. At the end of the anagen phase an unknown signal causes the follicle to go into the catagen phase.

Catagen phase

[edit]The catagen phase is a short transition stage that occurs at the end of the anagen phase.[18] It signals the end of the active growth of a hair. This phase lasts for about 2–3 weeks while the hair converts to a club hair, which is formed during the catagen phase when the part of the hair follicle in contact with the lower portion of the hair becomes attached to the hair shaft. A bulb of keratin attaches to the bottom tip of the hair and keeps it in place while a new hair begins to grow below it. A hair pulled out in this phase will have the bulb of keratin attached to it which appears as a small white ball on the end of the hair. This process cuts the hair off from its blood supply and from the cells that produce new hair. When a club hair is completely formed, about a 2-week process, the hair follicle enters the telogen phase.

Telogen phase

[edit]The telogen phase is the resting phase of the hair follicle, about three months.[19] When the body is subjected to extreme stress, as much as 70 percent of hair can prematurely enter the telogen phase and begin to fall, causing a noticeable loss of hair. This condition is called telogen effluvium.[20] The club hair is the final product of a hair follicle in the telogen stage, and is a dead, fully keratinized hair.[11] Fifty to one-hundred club hairs are shed daily from a normal scalp.[11]

Timeline

[edit]- Scalp: The time these phases last varies from person to person. Different hair color and follicle shape affects the timings of these phases.

- Anagen phase, 2–8 years (occasionally much longer)

- Catagen phase, 2–3 weeks

- Telogen phase, around 3 months

- Eyebrows:

- Anagen phase, 4–7 months

- Catagen phase, 3–4 weeks

- Telogen phase, about 9 months

Clinical significance

[edit]Disease

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2018) |

There are many human diseases in which abnormalities in hair appearance, texture or growth are early signs of local disease of the hair follicle or systemic illness. Well known diseases of the hair follicle include alopecia or hair loss, hirsutism or excess hair growth, and lupus erythematosus.[3] Therefore, understanding the function of the normal hair follicle is fundamental to diagnosing and treating many dermatologic and systemic diseases with hair abnormalities.[3] Studies of Witka et al. 2020 has shown the role of microbiome in the biology, immunology and diseases of scalp hair follicle. Studies further shown that change in hair follicle microbiome result into scalp disease like; Seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp and dandruff, Folliculitis decalvans, Androgenetic alopecia, Scalp psoriasis and Alopecia areata.[21]

-

male alopecia

-

Alopecia scale

Hair restoration

[edit]Hair follicles form the basis of the two primary methods of hair transplantation in hair restoration, Follicular Unit Transplantation (FUT) and follicular unit extraction (FUE). In each of these methods, naturally occurring groupings of one to four hairs, called follicular units, are extracted from the hair restoration patient and then surgically implanted in the balding area of the patient's scalp, known as the recipient area. These follicles are extracted from donor areas of the scalp, or other parts of the body, which are typically resistant to the miniaturization effects of the hormone DHT. It is this miniaturization of the hair shaft that is the primary predictive indicator of androgenetic alopecia,[22] commonly referred to as male pattern baldness or male hair loss. When these DHT-resistant follicles are transplanted to the recipient area, they continue to grow hair in the normal hair cycle, thus providing the hair restoration patient with permanent, naturally-growing hair.

While hair transplantation dates back to the 1950s,[23] and plucked human hair follicle cell culture in vitro to the early 1980s,[24] it was not until 1995 when hair transplantation using individual follicular units was introduced into medical literature.[25]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Blume-Peytavi, Ulrike (2008). Hair growth and disorders. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-46911-7. OCLC 272298782.

- ^ a b Erjavec SO, Gelfman S, Abdelaziz AR, Lee EY, Monga I, Alkelai A, Ionita-Laza I, Petukhova L, Christiano AM (Feb 2022). "Whole exome sequencing in Alopecia Areata identifies rare variants in KRT82". Nat Commun. 13 (1): 800. Bibcode:2022NatCo..13..800E. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-28343-3. PMC 8831607. PMID 35145093.

- ^ a b c Gilhar, Amos; Etzioni, Amos; Paus, Ralf (2012-04-19). "Alopecia areata". The New England Journal of Medicine. 366 (16): 1515–1525. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1103442. ISSN 1533-4406. PMID 22512484. S2CID 5201399.

- ^ Pawlina, Wojciech; Ross, Michael W.; Kaye, Gordon I. (2003). Histology: a text and atlas: with cell and molecular biology. Hagerstown, Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-683-30242-4.

- ^ Ma DR; Yang EN; Lee ST (2004). "A review: the location, molecular characterisation and multipotency of hair follicle epidermal stem cells". Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 33 (6): 784–8. doi:10.47102/annals-acadmedsg.STlee. PMID 15608839. S2CID 20267123.

- ^ Cotsarelis G (2006). "Epithelial stem cells: a folliculocentric view". J. Invest. Dermatol. 126 (7): 1459–68. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700376. PMID 16778814.

- ^ Lin, K. K.; Andersen, B. (2008). "Have Hair Follicle Stem Cells Shed Their Tranquil Image?". Cell Stem Cell. 3 (6): 581–582. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2008.11.005. PMID 19041772.

- ^ "Histologic Diagnosis of Inflammatory Skin Diseases, Chapter 1. Embryologic, Histologic, and Anatomic Aspects". Derm101.com. Archived from the original on 2012-10-21.

- ^ Chernova, Olga (May 2014). "Scanning electron microscopy of the hair medulla of orangutan, chimpanzee, and man". Journal of Biological Sciences. 456 (1): 199–202. doi:10.1134/S0012496614030065. PMID 24985515. S2CID 6597226.

- ^ S.V, Kshirsagar (July 2009). "Comparative Study of Human and Animal Hair in Relation with Diameter and Medullary Index" (PDF). Indian Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 2 (3). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-12-22. Retrieved 2022-02-21.

- ^ a b c Paus R; Cotsarelis G (August 1999). "The biology of hair follicles". N. Engl. J. Med. 341 (7): 491–7. doi:10.1056/NEJM199908123410706. PMID 10441606.

- ^ "Hair Follicle". 2017-11-27. Archived from the original on 2018-12-16. Retrieved 2018-12-18. Wednesday, 19 December 2018

- ^ Matsumura H, Mohri Y, Binh NT, Morinaga H, Fukuda M, Ito M, Kurata S, Hoeijmakers J, Nishimura EK (2016). "Hair follicle aging is driven by transepidermal elimination of stem cells via COL17A1 proteolysis". Science. 351 (6273) aad4395. doi:10.1126/science.aad4395. PMID 26912707. S2CID 5078019.

- ^ K. S. Stenn & R. Paus (1 January 2001). "Controls of Hair Follicle Cycling". Physiological Reviews. 81 (1): 449–494. doi:10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.449. PMID 11152763. S2CID 35922975. (comprehensive topic review, successor to landmark review of 1954 by HB Chase)

- ^ Hwang, J.; Mehrani, T.; Millar, S. E.; Morasso, M. I. (2008). "Dlx3 is a crucial regulator of hair follicle differentiation and cycling". Development. 135 (18): 3149–3159. doi:10.1242/dev.022202. PMC 2707782. PMID 18684741.

- ^ Park, G. T.; Morasso, M. I. (2002). "Bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) transactivates Dlx3 through Smad1 and Smad4: Alternative mode for Dlx3 induction in mouse keratinocytes". Nucleic Acids Research. 30 (2): 515–522. doi:10.1093/nar/30.2.515. PMC 99823. PMID 11788714.

- ^ Brannon, Maryland, Heather. "Anagen Phase". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2015-09-06. Retrieved 2007-11-14.

- ^ Brannon, Maryland, Heather. "Categen Phase". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2015-09-06. Retrieved 2007-11-14.

- ^ Brannon, Maryland, Heather. "Telogen Phase". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2009-02-08. Retrieved 2007-11-14.

- ^ S Malkud (1 September 2015). "Telogen Effluvium: A Review". J Clin Diagn Res. 9 (9): WE01–3. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2015/15219.6492. PMC 4606321. PMID 26500992.

- ^ Witka, Katarzyna Polak; Rudnicka, Lidia; Peytavi, Ulrike Blume; Vogt, Annika (2020). "The role of the microbiome in scalp hair follicle biology and disease". Experimental Dermatology. 29 (3): 286–294. doi:10.1111/exd.13935. PMID 30974503. S2CID 109939740.

- ^ Bernstein RM; Rassman WR (September 1997). "Follicular transplantation. Patient evaluation and surgical planning". Dermatol Surg. 23 (9): 771–84, discussion 801–5. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1997.tb00417.x. PMID 9311372. S2CID 32873299.

- ^ Orentreich N (November 1959). "Autografts in alopecias and other selected dermatological conditions". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 83 (3): 463–79. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1960.tb40920.x. PMID 14429008. S2CID 35356631.

- ^ Wells J; Sieber VK (December 1985). "Morphological characteristics of cells derived from plucked human hair in vitro". Br. J. Dermatol. 113 (6): 669–75. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1985.tb02402.x. PMID 2420350. S2CID 31137232.

- ^ Bernstein RM; Rassman WR; Szaniawski W; Halperin A (1995). "Follicular Transplantation". Intl J Aesthetic Restorative Surgery. 3: 119–32. ISSN 1069-5249. OCLC 28084113.

External links

[edit] Media related to Hair follicle at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hair follicle at Wikimedia Commons