Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sebaceous gland

View on Wikipedia

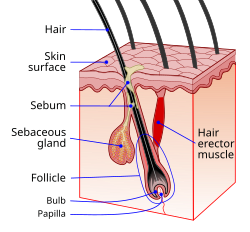

Schematic view of hair follicle and sebaceous gland | |

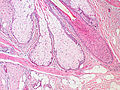

Cross-section of all skin layers. A hair follicle with associated structures. (Sebaceous glands labeled at center left.) | |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| MeSH | D012627 |

| TA98 | A16.0.00.030 A15.2.07.044 |

| TA2 | 7082 |

| FMA | 59160 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

A sebaceous gland or oil gland[1] is a microscopic exocrine gland in the skin that opens into a hair follicle to secrete an oily or waxy matter, called sebum, which lubricates the hair and skin of mammals.[2] In humans, sebaceous glands occur in the greatest number on the face and scalp, but also on all parts of the skin except the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. In the eyelids, meibomian glands, also called tarsal glands, are a type of sebaceous gland that secrete a special type of sebum into tears. Surrounding the female nipples, areolar glands are specialized sebaceous glands for lubricating the nipples. Fordyce spots are benign, visible, sebaceous glands found usually on the lips, gums and inner cheeks, and genitals.

Structure

[edit]Location

[edit]In humans, sebaceous glands are found throughout all areas of the skin, except the palms of the hands and soles of the feet.[3] There are two types of sebaceous glands: those connected to hair follicles and those that exist independently.[4]

Sebaceous glands are found in hair-covered areas, where they are connected to hair follicles. One or more glands may surround each hair follicle, and the glands themselves are surrounded by arrector pili muscles, forming a pilosebaceous unit. The glands have an acinar structure (like a many-lobed berry), in which multiple glands branch off a central duct. The glands deposit sebum on the hairs and bring it to the skin surface along the hair shaft. The structure, consisting of hair, hair follicles, arrector pili muscles, and sebaceous glands, is an epidermal invagination known as a pilosebaceous unit.[4]

Sebaceous glands are also found in hairless areas (glabrous skin) of the eyelids, nose, penis, labia minora, the inner mucosal membrane of the cheek, and nipples.[4] Some sebaceous glands have unique names. Sebaceous glands on the lip and mucosa of the cheek, and on the genitalia, are known as Fordyce spots, and glands on the eyelids are known as meibomian glands. Sebaceous glands of the breast are also known as Montgomery's glands.[5]

Development

[edit]Sebaceous glands are first visible from the 13th to the 16th week of fetal development, as bulgings off hair follicles.[6] Sebaceous glands develop from the same tissue that gives rise to the epidermis of the skin. Overexpression of the signalling factors Wnt, Myc and SHH all increase the likelihood of sebaceous gland presence.[5]

The sebaceous glands of a human fetus secrete a substance called vernix caseosa, a waxy, translucent white substance coating the skin of newborns.[7] After birth, activity of the glands decreases until there is almost no activity during ages two–six years, and then increases to a peak of activity during puberty, due to heightened levels of androgens.[6]

-

Base of pilosebaceous unit

-

Insertion of sebaceous glands into hair shaft

-

Sagittal section through the upper eyelid

-

A hair follicle with associated structures

-

Scalp cross section showing hair follicle with sebaceous glands

Function

[edit]Relative to keratinocytes that make up the hair follicle, sebaceous glands are composed of huge cells (sebocytes) with many large vesicles that contain the sebum.[8] These cells express Na+ and Cl− ion channels, ENaC and CFTR (see Fig. 6 and Fig. 7 in reference[8]).

Sebaceous glands secrete the oily, waxy substance called sebum (Latin for 'fat, tallow') that is made of triglycerides, wax esters, squalene, and metabolites of fat-producing cells. Sebum lubricates the skin and hair of mammals.[9] Sebaceous secretions in conjunction with apocrine glands also play an important thermoregulatory role. In hot conditions, the secretions emulsify the sweat produced by the eccrine sweat glands and this produces a sheet of sweat that is not readily lost in drops of sweat. This is of importance in delaying dehydration. In colder conditions, the nature of sebum becomes more lipid, and in coating the hair and skin, rain is effectively repelled.[10][11]

Sebum is produced in a holocrine process, in which sebocyte cells within the sebaceous gland rupture and disintegrate as they release the sebum and the cell remnants are secreted together with the sebum.[12][13] The cells are constantly replaced by mitosis at the base of the duct.[4]

Sebum

[edit]Sebum is secreted by the sebaceous gland in humans. It is primarily composed of triglycerides (≈41%), wax esters (≈26%), squalene (≈12%), and free fatty acids (≈16%).[7][14] The composition of sebum varies across species.[14] Wax esters and squalene are unique to sebum and not produced as final products anywhere else in the body.[5] Sapienic acid is a sebum fatty acid that is unique to humans, and is implicated in the development of acne.[15] Sebum is odorless, but its breakdown by bacteria can produce strong odors.[16]

Sex hormones are known to affect the rate of sebum secretion; androgens such as testosterone have been shown to stimulate secretion, and estrogens have been shown to inhibit secretion.[17] Dihydrotestosterone acts as the primary androgen in the prostate and in hair follicles.[18][19]

Immune function and nutrition

[edit]Sebaceous glands are part of the body's integumentary system and serve to protect the body against microorganisms. Sebaceous glands secrete acids that form the acid mantle. This is a thin, slightly acidic film on the surface of the skin that acts as a barrier to microbes that might penetrate the skin.[20] The pH of the skin is between 4.5 and 6.2,[21] an acidity that helps to neutralize the alkaline nature of contaminants.[22] Sebaceous lipids help maintain the integrity of the skin barrier[10][23][24] and supply vitamin E to the skin.[25]

Unique sebaceous glands

[edit]During the last three months of fetal development, the sebaceous glands of the fetus produce vernix caseosa, a waxy white substance that coats the skin to protect it from amniotic fluid.[26]

The areolar glands are in the areola that surrounds the nipple in the female breast. These glands secrete an oily fluid that lubricates the nipple, and also secrete volatile compounds that are thought to serve as an olfactory stimulus for the newborn. During pregnancy and lactation these glands, also called Montgomery's glands, become enlarged.[27]

Meibomian glands, in the eyelids, secrete a form of sebum called meibum onto the eye, that slows the evaporation of tears.[28] They also serve to create an airtight seal when the eyes are closed, and their lipid quality also prevents the eyelids from sticking together. They attach directly to the follicles of the eyelashes, which are arranged vertically within the tarsal plates of the eyelids.

Fordyce spots, or Fordyce granules, are ectopic sebaceous glands found on the genitals and oral mucosa. They show themselves as yellowish-white milia (milk spots).[29]

Earwax is partly composed of sebum produced by glands in the ear canal. These secretions are viscous and have a high lipid content, which provides good lubrication.[30]

Clinical significance

[edit]

Sebaceous glands are involved in skin problems such as acne and keratosis pilaris. In the skin pores, sebum and keratin can create a hyperkeratotic plug called a comedo.

Acne

[edit]Acne is a common occurrence, particularly during puberty in teenagers, and is thought to relate to an increased production of sebum due to hormonal factors. The increased production of sebum can lead to a blockage of the sebaceous gland duct. This can cause a comedo (commonly called a blackhead or a whitehead), which can lead to infection, particularly by the bacteria Cutibacterium acnes. This can inflame the comedones, which then change into the characteristic acne lesions. Comedones generally occur on the areas with more sebaceous glands, particularly the face, shoulders, upper chest and back. Comedones may be "black" or "white" depending on whether the entire pilosebaceous unit, or just the sebaceous duct, is blocked.[31] Sebaceous filaments—innocuous build-ups of sebum—are often mistaken for whiteheads.

There are many treatments available for acne from reducing sugars in the diet, to medications that include antibiotics, benzoyl peroxide, retinoids, and hormonal treatments.[31] Retinoids reduce the amount of sebum produced by the sebaceous glands.[32] Should the usual treatments fail, the presence of the Demodex mite could be looked for as the possible cause.[33]

Other

[edit]Other conditions that involve the sebaceous glands include:

- Seborrhoea refers to overactive sebaceous glands, a cause of oily skin[5] or hair.[16]

- Sebaceous hyperplasia, referring to excessive proliferation of the cells within the glands, and visible macroscopically as small papules on the skin, particularly on the forehead, nose and cheeks.[34]

- Seborrhoeic dermatitis, a chronic, usually mild form of dermatitis effected by changes in the sebaceous glands.[35] In newborn infants, seborrhoea dermatitis can occur as cradle cap.

- Seborrheic-like psoriasis (also known as "Sebopsoriasis",[36] and "Seborrhiasis") is a skin condition characterized by psoriasis with an overlapping seborrheic dermatitis.[3]: 193

- Sebaceous adenoma, a benign slow-growing tumour—which may, however, in rare cases be a precursor to a cancer syndrome known as Muir–Torre syndrome.[5]

- Sebaceous carcinoma, an uncommon and aggressive cutaneous tumour.[37]

- Sebaceous cyst is a term used to refer to both an epidermoid cyst and a pilar cyst, though neither of these contain sebum, only keratin and do not originate in the sebaceous gland and so are not true sebaceous cysts. A true sebaceous cyst is relatively rare and is known as a steatocystoma.[38]

- Nevus sebaceous, a hairless region or plaque on the scalp or skin, caused by an overgrowth of sebaceous glands. The condition is congenital and the plaque becomes thicker into adulthood.[39]

- Phymatous rosacea is a cutaneous condition characterized by an overgrowth of sebaceous glands.[36]

History

[edit]The word sebaceous, meaning 'consisting of sebum', was first termed in 1728 and comes from the Latin for 'tallow'.[40] Sebaceous glands have been documented since at least 1746 by Jean Astruc, who defined them as "...the glands which separate the fat."[41]: viii He describes them in the oral cavity and on the head, eyelids, and ears, as "universally" acknowledged.[41]: 22–25 viii Astruc describes them being blocked by "small animals" that are "implanted" in the excretory ducts[41]: 64 and attributes their presence in the oral cavity to apthous ulcers, noting that "these glands naturally [secrete] a viscous humour, which puts on various colours and consistencies... in its natural state is very mild, balsamic, and intended to wet and lubricate the mouth".[41]: 85–86 In The Principles of Physiology 1834, Andrew Combe noted that the glands were not present in the palms of the hands or soles of the feet.[42]

In animals

[edit]The preputial glands of mice and rats are large modified sebaceous glands that produce pheromones used for territorial marking.[5] These and the scent glands in the flanks of hamsters have a similar composition to human sebaceous glands, are androgen responsive, and have been used as a basis for study.[5] Some species of bat, including the Mexican free-tailed, have a specialized sebaceous gland occurring on the throat called a "gular gland".[44] This gland is present more frequently in males than females, and it is hypothesized that the secretions of the gland are used for scent-marking.[45]

Sebaceous adenitis is an autoimmune disease that affects sebaceous glands. It is mainly known to occur in dogs, particularly poodles and akitas, where it is thought to be generally autosomal recessively inherited. It has also been described in cats, and one report describes this condition in a rabbit. In these animals, it causes hair loss, though the nature and distribution of the hair loss differs greatly.[46]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Hair follicle sebaceous gland: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia Image". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 6 June 2023. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ Lovászi, Marianna; Szegedi, Andrea; Zouboulis, Christos C.; Törőcsik, Dániel (17 October 2017). "Sebaceous-immunobiology is orchestrated by sebum lipids". Dermato-endocrinology. 9 (1) e1375636. Informa UK Limited. doi:10.1080/19381980.2017.1375636. ISSN 1938-1980. PMC 5821166. PMID 29484100.

- ^ a b James, William D.; Berger, Timothy; Elston, Dirk M. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- ^ a b c d Young, Barbra; Lowe, James S; Stevens, Alan; Heath, John W; Deakin, Philip J (March 2006). Wheater's Functional Histology (5 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 175–178. ISBN 978-0-443-06850-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g Smith, K. R.; Thiboutot, D. M. (2007). "Thematic Review Series: Skin Lipids. Sebaceous Gland Lipids: Friend Or Foe?". Journal of Lipid Research. 49 (2): 271–281. doi:10.1194/jlr.R700015-JLR200. PMID 17975220.

- ^ a b Thiboutot, D (July 2004). "Regulation of human sebaceous glands". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 123 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1747.2004.t01-2-.x. PMID 15191536.

- ^ a b Thody, A. J.; Shuster, S. (1989). "Control and Function of Sebaceous Glands". Physiological Reviews. 69 (2): 383–416. doi:10.1152/physrev.1989.69.2.383. PMID 2648418.

- ^ a b Hanukoglu I, Boggula VR, Vaknine H, Sharma S, Kleyman T, Hanukoglu A (January 2017). "Expression of epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) and CFTR in the human epidermis and epidermal appendages". Histochemistry and Cell Biology. 147 (6): 733–748. doi:10.1007/s00418-016-1535-3. PMID 28130590. S2CID 8504408. Archived from the original on 17 November 2019. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ Dellmann's textbook of veterinary histology (405 pages), Jo Ann Coers Eurell, Brian L. Frappier, 2006, p.29, weblink: Books-Google-RTOC.

- ^ a b Zouboulis CC (2004). "Acne and Sebaceous Gland Function". Clinics in Dermatology. 22 (5): 360–366. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2004.03.004. PMID 15556719.

- ^ Porter AM (2001). "Why do we have apocrine and sebaceous glands?". J R Soc Med. 94 (5): 236–7. doi:10.1177/014107680109400509. PMC 1281456. PMID 11385091.

- ^ Victor Eroschenko, diFiore's Atlas of Histology with functional correlations, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 10th edition, 2005. p. 41

- ^ Dorland's (2012). Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (32nd ed.). Elsevier Saunders. p. 866. ISBN 978-0-19-856878-0.

- ^ a b Cheng JB, Russell DW (September 2004). "Mammalian Wax Biosynthesis II: Expression cloning of wax synthase cDNAs encoding a member of the acyltransferase enzyme family". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (36): 37798–807. doi:10.1074/jbc.M406226200. PMC 2743083. PMID 15220349.

- ^ Webster, Guy F.; Anthony V. Rawlings (2007). Acne and Its Therapy. Basic and clinical dermatology. Vol. 40. CRC Press. p. 311. ISBN 978-0-8247-2971-4.

- ^ a b Draelos, Zoe Diana (2005). Hair care: an illustrated dermatologic handbook. London; New York: Taylor & Francis. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-84184-194-6. Archived from the original on 24 February 2024. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ Sweeney TM (December 1968). "The Effect of Estrogen and Androgen on the Sebaceous Gland Turnover Time". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 53 (1): 8–10. doi:10.1038/jid.1969.100. PMID 5793140.

- ^ Amory JK, Anawalt BD, Matsumoto AM, Page ST, Bremner WJ, Wang C, Swerdloff RS, Clark RV (June 2008). "The effect of 5alpha-reductase inhibition with dutasteride and finasteride on bone mineral density, serum lipoproteins, hemoglobin, prostate specific antigen and sexual function in healthy young men". J. Urol. 179 (6): 2333–8. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.145. PMC 2684818. PMID 18423697.

- ^ Wilkinson, P.F.; Millington, R. (1983). Skin (Digitally printed ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge university press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-521-24122-9.

- ^ Monika-Hildegard Schmid-Wendtner; Korting Schmid-Wendtner (2007). Ph and Skin Care. ABW Wissenschaftsverlag. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-3-936072-64-8. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ Zlotogorski A (1987). "Distribution of skin surface pH on the forehead and cheek of adults". Arch. Dermatol. Res. 279 (6): 398–401. doi:10.1007/bf00412626. PMID 3674963. S2CID 3065931.

- ^ Schmid MH, Korting HC (1995). "The concept of the acid mantle of the skin: its relevance for the choice of skin cleansers" (PDF). Dermatology. 191 (4): 276–80. doi:10.1159/000246568. PMID 8573921. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2011.

- ^ Youn, S. W. (2010). "The Role of Facial Sebum Secretion in Acne Pathogenesis: Facts and Controversies". Clinics in Dermatology. 28 (1): 8–11. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2009.03.011. PMID 20082943.

- ^ Drake, David R.; Brogden, Kim A.; Dawson, Deborah V.; Wertz, Philip W. (10 May 2011). "Thematic Review Series: Skin Lipids. Antimicrobial lipids at the skin surface". Journal of Lipid Research. 49 (1): 4–11. doi:10.1194/jlr.R700016-JLR200. PMID 17906220. S2CID 10119536. Archived from the original on 9 January 2020. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ Thiele, Jens J.; Weber, Stefan U.; Packer, Lester (1999). "Sebaceous Gland Secretion is a Major Physiologic Route of Vitamin E Delivery to Skin". Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 113 (6): 1006–1010. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00794.x. PMID 10594744.

- ^ Zouboulis, Christos C.; Baron, Jens Malte; Böhm, Markus; Kippenberger, Stefan; Kurzen, Hjalmar; Reichrath, Jörg; Thielitz, Anja (2008). "Frontiers in Sebaceous Gland Biology and Pathology". Experimental Dermatology. 17 (6): 542–551. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00725.x. PMID 18474083.

- ^ Doucet, Sébastien; Soussignan, Robert; Sagot, Paul; Schaal, Benoist (2009). Hausberger, Martine (ed.). "The Secretion of Areolar (Montgomery's) Glands from Lactating Women Elicits Selective, Unconditional Responses in Neonates". PLOS ONE. 4 (10) e7579. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7579D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007579. PMC 2761488. PMID 19851461.

- ^ McCulley, JP; Shine, WE (March 2004). "The lipid layer of tears: dependent on meibomian gland function". Experimental Eye Research. 78 (3): 361–5. doi:10.1016/s0014-4835(03)00203-3. PMID 15106913.

- ^ Dorland's (2012). Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (32nd ed.). Elsevier Saunders. p. 802. ISBN 978-0-19-856878-0.

- ^ Roeser, RJ; Ballachanda, BB (December 1997). "Physiology, pathophysiology, and anthropology/epidemiology of human earcanal secretions". Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. 8 (6): 391–400. PMID 9433685.

- ^ a b Colledge N, Walker B, Ralston S, eds. (2010). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 1267–1268. ISBN 978-0-7020-3085-7.

- ^ Farrell LN, Strauss JS, Stranieri AM (December 1980). "The treatment of severe cystic acne with 13-cis-retinoic acid. Evaluation of sebum production and the clinical response in a multiple-dose trial". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 3 (6): 602–11. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(80)80074-0. PMID 6451637.

- ^ Zhao YE, Peng Y, Wang XL, Wu LP, Wang M, Yan HL, Xiao SX (2011). "Facial dermatosis associated with Demodex: a case-control study". J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 12 (12): 1008–15. doi:10.1631/jzus.B1100179. PMC 3232434. PMID 22135150.

- ^ James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. p. 662. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- ^ Dessinioti, C.; Katsambas, A. (2013). "Seborrheic dermatitis: etiology, risk factors, and treatments: facts and controversies". Clin Dermatol. 31 (4): 343–51. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.01.001. PMID 23806151.

- ^ a b Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- ^ Nelson BR, Hamlet KR, Gillard M, Railan D, Johnson TM (July 1995). "Sebaceous carcinoma". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 33 (1): 1–15, quiz 16–8. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(95)90001-2. PMID 7601925.

- ^ Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CA, Bouquot JE (2002). Oral & maxillofacial pathology (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-7216-9003-2.

- ^ Kovich O, Hale E (2005). "Nevus sebaceus". Dermatology Online Journal. 11 (4): 16. doi:10.5070/D33BQ5524C. PMID 16403388. Archived from the original on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Sebaceous". Etymology Online. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d Astruc, Jean (1746). A General and Compleat Treatise on All the Diseases Incident to Children. J. Nourse. p. 3.

Sebaceous glands.

- ^ Rosenthal, Stanley A; Furnari, Domenica (1958). "Slide Agglutination as a Presumptive Test in the Laboratory Diagnosis of Candida Albicans1". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 31 (5): 251–253. doi:10.1038/jid.1958.50. PMID 13598929.

- ^ Dobson, G. E. (1878). Catalogue of the Chiroptera in the collection of the British Museum. Order of the Trustees.

- ^ Gutierrez, Mercedes; Aoki, Agustin (1973). "Fine structure of the gular gland of the free-tailed bat Tadarida brasiliensis". Journal of Morphology. 141 (3): 293–305. doi:10.1002/jmor.1051410305. PMID 4753444. S2CID 3093610.

- ^ Heideman, P. D., Erickson, K. R., & Bowles, J. B. (1990). Notes on the breeding biology, gular gland and roost habits of Molossus sinaloae (Chiroptera, Molossidae) Archived 21 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde, 55(5), 303-307.

- ^ Lars Mecklenburg; Monika Linek; Desmond J. Tobin (15 September 2009). Hair Loss Disorders in Domestic Animals. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 269–. ISBN 978-0-8138-1934-1. Archived from the original on 24 February 2024. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

External links

[edit]- Histology image: 08801loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- Sebaceous+Glands at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

![Example of a gular gland in a male black bonneted bat[43]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2e/Cheiromeles_torquatus.jpg/631px-Cheiromeles_torquatus.jpg)