Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Analog Science Fiction and Fact

View on Wikipedia

Analog Science Fiction and Fact is an American science fiction magazine published under various titles since 1930. Originally titled Astounding Stories of Super-Science, the first issue was dated January 1930, published by William Clayton, and edited by Harry Bates. Clayton went bankrupt in 1933 and the magazine was sold to Street & Smith. The new editor was F. Orlin Tremaine, who soon made Astounding the leading magazine in the nascent pulp science fiction field, publishing well-regarded stories such as Jack Williamson's Legion of Space and John W. Campbell's "Twilight". At the end of 1937, Campbell took over editorial duties under Tremaine's supervision, and the following year Tremaine was let go, giving Campbell more independence. Over the next few years Campbell published many stories that became classics in the field, including Isaac Asimov's Foundation series, A. E. van Vogt's Slan, and several novels and stories by Robert A. Heinlein. The period beginning with Campbell's editorship is often referred to as the Golden Age of Science Fiction.

By 1950, new competition had appeared from Galaxy Science Fiction and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction. Campbell's interest in some pseudo-science topics, such as Dianetics (an early non-religious version of Scientology), alienated some of his regular writers, and Astounding was no longer regarded as the leader of the field, though it did continue to publish popular and influential stories: Hal Clement's novel Mission of Gravity appeared in 1953, and Tom Godwin's "The Cold Equations" appeared the following year. In 1960, Campbell changed the title of the magazine to Analog Science Fact & Fiction; he had long wanted to get rid of the word "Astounding" in the title, which he felt was too sensational. At about the same time Street & Smith sold the magazine to Condé Nast, and the name changed again to its current form by 1965. Campbell remained as editor until his death in 1971.

Ben Bova took over from 1972 to 1978, and the character of the magazine changed noticeably, since Bova was willing to publish fiction that included sexual content and profanity. Bova published stories such as Frederik Pohl's "The Gold at the Starbow's End", which was nominated for both a Hugo and Nebula Award, and Joe Haldeman's "Hero", the first story in the Hugo and Nebula Award–winning "Forever War" sequence; Pohl had been unable to sell to Campbell, and "Hero" had been rejected by Campbell as unsuitable for the magazine. Bova won five consecutive Hugo Awards for his editing of Analog.

Bova was followed by Stanley Schmidt, who continued to publish many of the same authors who had been contributing for years; the result was some criticism of the magazine as stagnant and dull, though Schmidt was initially successful in maintaining circulation. The title was sold to Davis Publications in 1980, then to Dell Magazines in 1992. Crosstown Publications acquired Dell in 1996 and remains the publisher. Schmidt continued to edit the magazine until 2012, when he was replaced by Trevor Quachri.

Publishing history

[edit]Clayton

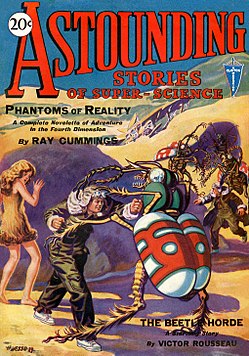

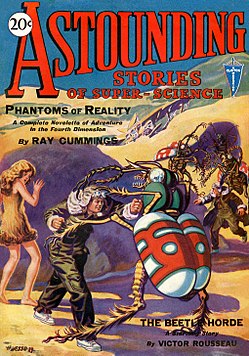

[edit]In 1926, Hugo Gernsback launched Amazing Stories, the first science fiction (sf) magazine. Gernsback had been printing scientific fiction stories for some time in his hobbyist magazines, such as Modern Electrics and Electrical Experimenter, but decided that interest in the genre was sufficient to justify a monthly magazine. Amazing was very successful, quickly reaching a circulation over 100,000.[1] William Clayton, a successful and well-respected publisher of several pulp magazines, considered starting a competitive title in 1928; according to Harold Hersey, one of his editors at the time, Hersey had "discussed plans with Clayton to launch a pseudo-science fantasy sheet".[2] Clayton was unconvinced, but the following year decided to launch a new magazine, mainly because the sheet on which the color covers of his magazines were printed had a space for one more cover. He suggested to Harry Bates, a newly hired editor, that they start a magazine of historical adventure stories. Bates proposed instead a science fiction pulp, to be titled Astounding Stories of Super Science, and Clayton agreed.[3][4]

| Issue data for 1930 to 1980 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

| 1930 | 1/1 | 1/2 | 1/3 | 2/1 | 2/2 | 2/3 | 3/1 | 3/2 | 3/3 | 4/1 | 4/2 | 4/3 |

| 1931 | 5/1 | 5/2 | 5/3 | 6/1 | 6/2 | 6/3 | 7/1 | 7/2 | 7/3 | 8/1 | 8/2 | 8/3 |

| 1932 | 9/1 | 9/2 | 9/3 | 10/1 | 10/2 | 10/3 | 11/1 | 11/2 | ||||

| 1933 | 11/3 | 12/1 | 12/2 | 12/3 | 12/4 | |||||||

| 1934 | 12/5 | 12/6 | 13/1 | 13/2 | 13/3 | 13/4 | 13/5 | 13/6 | 14/1 | 14/2 | 14/3 | 14/4 |

| 1935 | 14/5 | 14/6 | 15/1 | 15/2 | 15/3 | 15/4 | 15/5 | 15/6 | 16/1 | 16/2 | 16/3 | 16/4 |

| 1936 | 16/5 | 16/6 | 17/1 | 17/2 | 17/3 | 17/4 | 17/5 | 17/6 | 18/1 | 18/2 | 18/3 | 18/4 |

| 1937 | 18/5 | 18/6 | 19/1 | 19/2 | 19/3 | 19/4 | 19/5 | 19/6 | 20/1 | 20/2 | 20/3 | 20/4 |

| 1938 | 20/5 | 20/6 | 21/1 | 21/2 | 21/3 | 21/4 | 21/5 | 21/6 | 22/1 | 22/2 | 22/3 | 22/4 |

| 1939 | 22/5 | 22/6 | 23/1 | 23/2 | 23/3 | 23/4 | 23/5 | 23/6 | 24/1 | 24/2 | 24/3 | 24/4 |

| 1940 | 24/5 | 24/6 | 25/1 | 25/2 | 25/3 | 25/4 | 25/5 | 25/6 | 26/1 | 26/2 | 26/3 | 26/4 |

| 1941 | 26/5 | 26/6 | 27/1 | 27/2 | 27/3 | 27/4 | 27/5 | 27/6 | 28/1 | 28/2 | 28/3 | 28/4 |

| 1942 | 28/5 | 28/6 | 29/1 | 29/2 | 29/3 | 29/4 | 29/5 | 29/6 | 30/1 | 30/2 | 30/3 | 30/4 |

| 1943 | 30/5 | 30/6 | 31/1 | 31/2 | 31/3 | 31/4 | 31/5 | 31/6 | 32/1 | 32/2 | 32/3 | 32/4 |

| 1944 | 32/5 | 32/6 | 33/1 | 33/2 | 33/3 | 33/4 | 33/5 | 33/6 | 34/1 | 34/2 | 34/3 | 34/4 |

| 1945 | 34/5 | 34/6 | 35/1 | 35/2 | 35/3 | 35/4 | 35/5 | 35/6 | 36/1 | 36/2 | 36/3 | 36/4 |

| 1946 | 36/5 | 36/6 | 37/1 | 37/2 | 37/3 | 37/4 | 37/5 | 37/6 | 38/1 | 38/2 | 38/3 | 38/4 |

| 1947 | 38/5 | 38/6 | 39/1 | 39/2 | 39/3 | 39/4 | 39/5 | 39/6 | 40/1 | 40/2 | 40/3 | 40/4 |

| 1948 | 40/5 | 40/6 | 41/1 | 41/2 | 41/3 | 41/4 | 41/5 | 41/6 | 42/1 | 42/2 | 42/3 | 42/4 |

| 1949 | 42/5 | 42/6 | 43/1 | 43/2 | 43/3 | 43/4 | 43/5 | 43/6 | 44/1 | 44/2 | 44/3 | 44/4 |

| 1950 | 44/5 | 44/6 | 45/1 | 45/2 | 45/3 | 45/4 | 45/5 | 45/6 | 46/1 | 46/2 | 46/3 | 46/4 |

| 1951 | 46/5 | 46/6 | 47/1 | 47/2 | 47/3 | 47/4 | 47/5 | 47/6 | 48/1 | 48/2 | 48/3 | 48/4 |

| 1952 | 48/5 | 48/6 | 49/1 | 49/2 | 49/3 | 49/4 | 49/5 | 49/6 | 50/1 | 50/2 | 50/3 | 50/4 |

| 1953 | 50/5 | 50/6 | 51/1 | 51/2 | 51/3 | 51/4 | 51/5 | 51/6 | 52/1 | 52/2 | 52/3 | 52/4 |

| 1954 | 52/5 | 52/6 | 53/1 | 53/2 | 53/3 | 53/4 | 53/5 | 53/6 | 54/1 | 54/2 | 54/3 | 54/4 |

| 1955 | 54/5 | 54/6 | 55/1 | 55/2 | 55/3 | 55/4 | 55/5 | 55/6 | 56/1 | 56/2 | 56/3 | 56/4 |

| 1956 | 56/5 | 56/6 | 57/1 | 57/2 | 57/3 | 57/4 | 57/5 | 57/6 | 58/1 | 58/2 | 58/3 | 58/4 |

| 1957 | 58/5 | 58/6 | 59/1 | 59/2 | 59/3 | 59/4 | 59/5 | 59/6 | 60/1 | 60/2 | 60/3 | 60/4 |

| 1958 | 60/5 | 60/6 | 61/1 | 61/2 | 61/3 | 61/4 | 61/5 | 61/6 | 62/1 | 62/2 | 62/3 | 62/4 |

| 1959 | 62/5 | 62/6 | 63/1 | 63/2 | 63/3 | 63/4 | 63/5 | 63/6 | 64/1 | 64/2 | 64/3 | 64/4 |

| 1960 | 64/5 | 64/6 | 65/1 | 65/2 | 65/3 | 65/4 | 65/5 | 65/6 | 66/1 | 66/2 | 66/3 | 66/4 |

| 1961 | 66/5 | 66/6 | 67/1 | 67/2 | 67/3 | 67/4 | 67/5 | 67/6 | 68/1 | 68/2 | 68/3 | 68/4 |

| 1962 | 68/5 | 68/6 | 69/1 | 69/2 | 69/3 | 69/4 | 69/5 | 69/6 | 70/1 | 70/2 | 70/3 | 70/4 |

| 1963 | 70/5 | 70/6 | 71/1 | 71/2 | 71/3 | 71/4 | 71/5 | 71/6 | 72/1 | 72/2 | 72/3 | 72/4 |

| 1964 | 72/5 | 72/6 | 73/1 | 73/2 | 73/3 | 73/4 | 73/5 | 73/6 | 74/1 | 74/2 | 74/3 | 74/4 |

| 1965 | 74/5 | 74/6 | 75/1 | 75/2 | 75/3 | 75/4 | 75/5 | 75/6 | 76/1 | 76/2 | 76/3 | 76/4 |

| 1966 | 76/5 | 76/6 | 77/1 | 77/2 | 77/3 | 77/4 | 77/5 | 77/6 | 78/1 | 78/2 | 78/3 | 78/4 |

| 1967 | 78/5 | 78/6 | 79/1 | 79/2 | 79/3 | 79/4 | 79/5 | 79/6 | 80/1 | 80/2 | 80/3 | 80/4 |

| 1968 | 80/5 | 80/6 | 81/1 | 81/2 | 81/3 | 81/4 | 81/5 | 81/6 | 82/1 | 82/2 | 82/3 | 82/4 |

| 1969 | 82/5 | 82/6 | 83/1 | 83/2 | 83/3 | 83/4 | 83/5 | 83/6 | 84/1 | 84/2 | 84/3 | 84/4 |

| 1970 | 84/5 | 84/6 | 85/1 | 85/2 | 85/3 | 85/4 | 85/5 | 85/6 | 86/1 | 86/2 | 86/3 | 86/4 |

| 1971 | 86/5 | 86/6 | 87/1 | 87/2 | 87/3 | 87/4 | 87/5 | 87/6 | 88/1 | 88/2 | 88/3 | 88/4 |

| 1972 | 88/5 | 88/6 | 89/1 | 89/2 | 89/3 | 89/4 | 89/5 | 89/6 | 90/1 | 90/2 | 90/3 | 90/4 |

| 1973 | 90/5 | 90/6 | 91/1 | 91/2 | 91/3 | 91/4 | 91/5 | 91/6 | 92/1 | 92/2 | 92/3 | 92/4 |

| 1974 | 92/5 | 92/6 | 93/1 | 93/2 | 93/3 | 93/4 | 93/5 | 93/6 | 94/1 | 94/2 | 94/3 | 94/4 |

| 1975 | 94/5 | 95/2 | 95/3 | 95/4 | 95/5 | 95/6 | 95/7 | 95/8 | 95/9 | 95/10 | 95/11 | 95/12 |

| 1976 | 96/1 | 96/2 | 96/3 | 96/4 | 96/5 | 96/6 | 96/7 | 96/8 | 96/9 | 96/10 | 96/11 | 96/12 |

| 1977 | 97/1 | 97/2 | 97/3 | 97/4 | 97/5 | 97/6 | 97/7 | 97/8 | 97/9 | 97/10 | 97/11 | 97/12 |

| 1978 | 98/1 | 98/2 | 98/3 | 98/4 | 98/5 | 98/6 | 98/7 | 98/8 | 98/9 | 98/10 | 98/11 | 98/12 |

| 1979 | 99/1 | 99/2 | 99/3 | 99/4 | 99/5 | 99/6 | 99/7 | 99/8 | 99/9 | 99/10 | 99/11 | 99/12 |

| 1980 | 100/1 | 100/2 | 100/3 | 100/4 | 100/5 | 100/6 | 100/7 | 100/8 | 100/9 | 100/10 | 100/11 | 100/12 |

| Issues of Astounding Stories, showing volume/issue number; the apparent volume numbering error in January 1975 is in fact correct. The colors identify the editors for each issue:[5][6] Harry Bates F. Orlin Tremaine John W. Campbell Ben Bova Stanley Schmidt | ||||||||||||

Astounding was initially published by Publisher's Fiscal Corporation, a subsidiary of Clayton Magazines.[4][7][8] The first issue appeared in January 1930, with Bates as editor. Bates aimed for straightforward action-adventure stories, with scientific elements only present to provide minimal plausibility.[4] Clayton paid much better rates than Amazing and Wonder Stories—two cents a word on acceptance, rather than half a cent a word, on publication (or sometimes later)—and consequently Astounding attracted some of the better-known pulp writers, such as Murray Leinster, Victor Rousseau, and Jack Williamson.[3][4] In February 1931, the original name Astounding Stories of Super-Science was shortened to Astounding Stories.[9]

The magazine was profitable,[9] but the Great Depression caused Clayton problems. Normally a publisher would pay a printer three months in arrears, but when a credit squeeze began in May 1931, it led to pressure to reduce this delay. The financial difficulties led Clayton to start alternating the publication of his magazines, and he switched Astounding to a bimonthly schedule with the June 1932 issue. Some printers bought the magazines which were indebted to them: Clayton decided to buy his printer to prevent this from happening. This proved a disastrous move. Clayton did not have the money to complete the transaction, and in October 1932, Clayton decided to cease publication of Astounding, with the expectation that the January 1933 issue would be the last one. As it turned out, enough stories were in inventory, and enough paper was available, to publish one further issue, so the last Clayton Astounding was dated March 1933.[10] In April, Clayton went bankrupt, and sold his magazine titles to T.R. Foley for $100; Foley resold them in August to Street & Smith, a well-established publisher.[11][12][13]

Street and Smith

[edit]Science fiction was not entirely a departure for Street & Smith. They already had two pulp titles that occasionally ventured into the field: The Shadow, which had begun in 1931 and was tremendously successful, with a circulation over 300,000; and Doc Savage, which had been launched in March 1933.[14] They gave the post of editor of Astounding to F. Orlin Tremaine, an experienced editor who had been working for Clayton as the editor of Clues, and who had come to Street & Smith as part of the transfer of titles after Clayton's bankruptcy. Desmond Hall, who had also come from Clayton, was made assistant editor; because Tremaine was editor of Clues and Top-Notch, as well as Astounding, Hall did much of the editorial work, though Tremaine retained final control over the contents.[15]

The first Street & Smith issue was dated October 1933; until the third issue, in December 1933, the editorial team was not named on the masthead.[15] Street & Smith had an excellent distribution network, and they were able to get Astounding's circulation up to an estimated 50,000 by the middle of 1934.[16] The two main rival science fiction magazines of the day, Wonder Stories and Amazing Stories, each had a circulation about half that. Astounding was the leading science fiction magazine by the end of 1934, and it was also the largest, at 160 pages, and the cheapest, at 20 cents. Street & Smith's rates of one cent per word (sometimes more) on acceptance were not as high as the rates paid by Bates for the Clayton Astounding, but they were still better than those of the other magazines.[17]

Hall left Astounding in 1934 to become editor of Street & Smith's new slick magazine, Mademoiselle, and was replaced by R.V. Happel. Tremaine remained in control of story selection.[18] Writer Frank Gruber described Tremaine's editorial selection process in his book, The Pulp Jungle:[19]

As the stories came in Tremaine piled them up on a stack. All the stories intended for Clues in this pile, all those for Astounding in that stack. Two days before press time of each magazine, Tremaine would start reading. He would start at the top of the pile and read stories until he had found enough to fill the issue. Now, to be perfectly fair, Tremaine would take the stack of remaining stories and turn it upside down, so next month he would start with the stories that had been on the bottom this month.

Gruber pointed out that stories in the middle might go many months before Tremaine read them; the result was erratic response times that sometimes stretched to over 18 months.[20]

In 1936 the magazine switched from untrimmed to trimmed edges; Brian Stableford comments that this was "an important symbolic" step, as the other sf pulps were still untrimmed, making Astounding smarter-looking than its competitors.[4] Tremaine was promoted to assistant editorial director in 1937. His replacement as editor of Astounding was 27-year-old John W. Campbell, Jr. Campbell had made his name in the early 1930s as a writer, publishing space opera under his own name, and more thoughtful stories under the pseudonym "Don A. Stuart". He started working for Street & Smith in October 1937, so his initial editorial influence appeared in the issue dated December 1937. The March 1938 issue was the first that was fully his responsibility.[21][22] In early 1938, Street & Smith abandoned its policy of having editors-in-chief, with the result that Tremaine was made redundant. His departure, on May 1, 1938, gave Campbell a freer rein with the magazine.[23]

One of Campbell's first acts was to change the title from Astounding Stories to Astounding Science-Fiction, starting with the March 1938 issue. Campbell's editorial policy was targeted at the more mature readers of science fiction, and he felt that "Astounding Stories" did not convey the right image.[23] He intended to subsequently drop the "Astounding" part of the title, as well, leaving the magazine titled Science Fiction, but in 1939 a new magazine with that title appeared. Although "Astounding" was retained in the title, thereafter it was often printed in a color that made it much less visible than "Science-Fiction".[4] At the start of 1942 the price was increased, for the first time, to 25 cents; the magazine simultaneously switched to the larger bedsheet format, but this did not last. Astounding returned to pulp-size in mid-1943 for six issues, and then became the first science fiction magazine to switch to digest size in November 1943, increasing the number of pages to maintain the same total word count. The price remained at 25 cents through these changes in format.[7][24] The hyphen was dropped from the title with the November 1946 issue.[25]

The price increased again, to 35 cents, in August 1951.[7] In the late 1950s, it became apparent to Street & Smith that they were going to have to raise prices again. During 1959, Astounding was priced at 50 cents in some areas to find out what the impact would be on circulation. The results were apparently satisfactory, and the price was raised with the November 1959 issue.[26] The following year, Campbell finally achieved his goal of getting rid of the word "Astounding" in the magazine's title, changing it to Analog Science Fact/Science Fiction. The "/" in the title was often replaced by a symbol of Campbell's devising, resembling an inverted U pierced by a horizontal arrow and meaning "analogous to". The change began with the February 1960 issue, and was complete by October; for several issues both "Analog" and "Astounding" could be seen on the cover, with "Analog" becoming bolder and "Astounding" fading with each issue.[4][27]

Condé Nast

[edit]Street & Smith was acquired by Samuel Newhouse, the owner of Condé Nast, in August 1959, though Street & Smith was not merged into Condé Nast until the end of 1961.[28] Analog was the only digest-sized magazine in Condé Nast's inventory—all the others were slicks, such as Vogue. All the advertisers in these magazines had plates made up to take advantage of this size, and Condé Nast changed Analog to the larger size from the March 1963 issue to conform. The front and back signatures were changed to glossy paper, to carry both advertisements and scientific features. The change did not attract advertising support, however, and from the April 1965 issue Analog reverted to digest size once again. Circulation, which had been increasing before the change, was not harmed, and continued to increase while Analog was in slick format.[29] From the April 1965 issue the title switched the "fiction" and "fact" elements, so that it became Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact.[30]

Campbell died suddenly in July 1971, but there was enough material in Analog's inventory to allow the remaining staff to put together issues for the rest of the year.[31] Condé Nast had given the magazine very little attention, since it was both profitable and cheap to produce, but they were proud that it was the leading science fiction magazine. They asked Kay Tarrant, who had been Campbell's assistant, to help them find a replacement: she contacted regular contributors to ask for suggestions. Several well-known writers turned down the job; Poul Anderson did not want to leave California, and neither did Jerry Pournelle, who also felt the salary was too small. Before he died, Campbell had talked to Harry Harrison about taking over as editor, but Harrison did not want to live in New York. Lester del Rey and Clifford D. Simak were also rumored to have been offered the job, though Simak denied it; Frederik Pohl was interested, but suspected his desire to change the direction of the magazine lessened his chances with Condé Nast.[32] The Condé Nast vice president in charge of selecting the new editor decided to read both fiction and nonfiction writing samples from the applicants, since Analog's title included both "science fiction" and "science fact". He chose Ben Bova, afterwards telling Bova that his stories and articles "were the only ones I could understand".[32] January 1972 was the first issue to credit Bova on the masthead.[7]

Bova planned to stay for five years, to ensure a smooth transition after Campbell's sudden death; the salary was too low for him to consider remaining indefinitely. In 1975, he proposed a new magazine to Condé Nast management, to be titled Tomorrow Magazine; he wanted to publish articles about science and technology, leavened with some science fiction stories. Condé Nast was not interested, and refused to assist Analog with marketing or promotions. Bova resigned in June 1978, having stayed for a little longer than he had planned, and recommended Stanley Schmidt to succeed him. Schmidt's first issue was December 1978, though material purchased by Bova continued to appear for several months.[33]

Davis Publications, Dell Magazines, and Penny Publications

[edit]| Issue data for 1981 to 1983 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Issue dates | Volume numbering |

Number of issues | |

| 1981 | Four-weekly intervals from January 5 through December 7 |

101/1 to 101/13 | 13 |

| 1982 | Four-weekly intervals from January 4 through March 29. No April issue; then May to December, with an additional Mid-September issue. |

102/1 to 102/13 | 13 |

| 1983 | Monthly issues January to December, with an additional Mid-September issue. |

103/1 to 103/13 | 13 |

| Issue data for 1981 to 1983. Stanley Schmidt was editor throughout. | |||

In 1977, Davis Publications launched Isaac Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine, and after Bova's departure, Joel Davis, the owner of Davis Publications, contacted Condé Nast with a view to acquiring Analog. Analog had always been something of a misfit in Condé Nast's line up, which included Mademoiselle and Vogue, and by February 1980 the deal was agreed. The first issue published by Davis was dated September 1980.[34] Davis was willing to put some effort into marketing Analog, so Schmidt regarded the change as likely to be beneficial,[33] and in fact circulation quickly grew, reversing a gradual decline over the Bova years, from just over 92,000 in 1981 to almost 110,000 two years later. Starting with the first 1981 issue, Davis switched Analog to a four-weekly schedule, rather than monthly, to align the production schedule with a weekly calendar. Instead of being dated "January 1981", the first issue under the new regime was dated "January 5, 1981", but this approach led to newsstands removing the magazine much more quickly, since the date gave the impression that it was a weekly magazine. The cover date was changed back to the current month starting with the April 1982 issue, but the new schedule remained in place, with a "Mid-September" issue in 1982 and 1983, and "Mid-December" issues for more than a decade thereafter.[34] Circulation trended slowly down over the 1980s, to 83,000 for the year ending in 1990; by this time the great majority of readers were subscribers, as newsstand sales declined to only 15,000.[30]

| Issue data for 1984 to 2019 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Mid-Dec | |

| 1984 | 104/1 | 104/2 | 104/3 | 104/4 | 104/5 | 104/6 | 104/7 | 104/8 | 104/9 | 104/10 | 104/11 | 104/12 | 104/13 |

| 1985 | 105/1 | 105/2 | 105/3 | 105/4 | 105/5 | 105/6 | 105/7 | 105/8 | 105/9 | 105/10 | 105/11 | 105/12 | 105/13 |

| 1986 | 106/1 | 106/2 | 106/3 | 106/4 | 106/5 | 106/6 | 106/7 | 106/8 | 106/9 | 106/10 | 106/11 | 106/12 | 106/13 |

| 1987 | 107/1 | 107/2 | 107/3 | 107/4 | 107/5 | 107/6 | 107/7 | 107/8 | 107/9 | 107/10 | 107/11 | 107/12 | 107/13 |

| 1988 | 108/1 | 108/2 | 108/3 | 108/4 | 108/5 | 108/6 | 108/7 | 108/8 | 108/9 | 108/10 | 108/11 | 108/12 | 108/13 |

| 1989 | 109/1 | 109/2 | 109/3 | 109/4 | 109/5 | 109/6 | 109/7 | 109/8 | 109/9 | 109/10 | 109/11 | 109/12 | 109/13 |

| 1990 | 110/1 & 2 | 110/3 | 110/4 | 110/5 | 110/6 | 110/7 | 110/8 | 110/9 | 110/10 | 110/11 | 110/12 | 110/13 | 110/14 |

| 1991 | 111/1 & 2 | 111/3 | 111/4 | 111/5 | 111/6 | 111/7 | 111/8 & 9 | 111/10 | 111/11 | 111/12 | 111/13 | 111/14 | 111/15 |

| 1992 | 112/1 & 2 | 112/3 | 112/4 | 112/5 | 112/6 | 112/7 | 112/8 & 9 | 112/10 | 112/11 | 112/12 | 112/13 | 112/14 | 112/15 |

| 1993 | 113/1 & 2 | 113/3 | 113/4 | 113/5 | 113/6 | 113/7 | 113/8 & 9 | 113/10 | 113/11 | 113/12 | 113/13 | 113/14 | 113/15 |

| 1994 | 114/1 & 2 | 114/3 | 114/4 | 114/5 | 114/6 | 114/7 | 114/8 & 9 | 114/10 | 114/11 | 114/12 | 114/13 | 114/14 | 114/15 |

| 1995 | 115/1 & 2 | 115/3 | 115/4 | 115/5 | 115/6 | 115/7 | 115/8 & 9 | 115/10 | 115/11 | 115/12 | 115/13 | 115/14 | 115/15 |

| 1996 | 116/1 | 116/2 | 116/3 | 116/4 | 116/5 | 116/6 | 116/7 | 116/8 | 116/9 | 116/10 | 116/11 | 116/12 | |

| 1997 | 117/1 | 117/2 | 117/3 | 117/4 | 117/5 | 117/6 | 117/7 & 8 | 117/9 | 117/10 | 117/11 | 117/12 | ||

| 1998 | 118/1 | 118/2 | 118/3 | 118/4 | 118/5 | 118/6 | 118/7 & 8 | 118/9 | 118/10 | 118/11 | 118/12 | ||

| 1999 | 119/1 | 119/2 | 119/3 | 119/4 | 119/5 | 119/6 | 119/7 & 8 | 119/9 | 119/10 | 119/11 | 119/12 | ||

| 2000 | 120/1 | 120/2 | 120/3 | 120/4 | 120/5 | 120/6 | 120/7 & 8 | 120/9 | 120/10 | 120/11 | 120/12 | ||

| 2001 | 121/1 | 121/2 | 121/3 | 121/4 | 121/5 | 121/6 | 121/7 & 8 | 121/9 | 121/10 | 121/11 | 121/12 | ||

| 2002 | 122/1 | 122/2 | 122/3 | 122/4 | 122/5 | 122/6 | 122/7 & 8 | 122/9 | 122/10 | 122/11 | 122/12 | ||

| 2003 | 123/1 | 123/2 | 123/3 | 123/4 | 123/5 | 123/6 | 123/7 & 8 | 123/9 | 123/10 | 123/11 | 123/12 | ||

| 2004 | 124/1 & 2 | 124/3 | 124/4 | 124/5 | 124/6 | 124/7 & 8 | 124/9 | 124/10 | 124/11 | 124/12 | |||

| 2005 | 125/1 & 2 | 125/3 | 125/4 | 125/5 | 125/6 | 125/7 & 8 | 125/9 | 125/10 | 125/11 | 125/12 | |||

| 2006 | 126/1 & 2 | 126/3 | 126/4 | 126/5 | 126/6 | 126/7 & 8 | 126/9 | 126/10 | 126/11 | 126/12 | |||

| 2007 | 126/1 & 2 | 127/3 | 127/4 | 127/5 | 127/6 | 127/7 & 8 | 127/9 | 127/10 | 127/11 | 127/12 | |||

| 2008 | 128/1 & 2 | 128/3 | 128/4 | 128/5 | 128/6 | 128/7 & 8 | 128/9 | 128/10 | 128/11 | 128/12 | |||

| 2009 | 129/1 & 2 | 129/3 | 129/4 | 129/5 | 129/6 | 129/7 & 8 | 129/9 | 129/10 | 129/11 | 129/12 | |||

| 2010 | 130/1 & 2 | 130/3 | 130/4 | 130/5 | 130/6 | 130/7 & 8 | 130/9 | 130/10 | 130/11 | 130/12 | |||

| 2011 | 131/1 & 2 | 131/3 | 131/4 | 131/5 | 131/6 | 131/7 & 8 | 131/9 | 131/10 | 131/11 | 131/12 | |||

| 2012 | 132/1 & 2 | 132/3 | 132/4 | 132/5 | 132/6 | 132/7 & 8 | 132/9 | 132/10 | 132/11 | 132/12 | |||

| 2013 | 133/1 & 2 | 133/3 | 133/4 | 133/5 | 133/6 | 133/7 & 8 | 133/9 | 133/10 | 133/11 | 133/12 | |||

| 2014 | 134/1 & 2 | 134/3 | 134/4 | 134/5 | 134/6 | 134/7 & 8 | 134/9 | 134/10 | 134/11 | 134/12 | |||

| 2015 | 135/1 & 2 | 135/3 | 135/4 | 135/5 | 135/6 | 135/7 & 8 | 135/9 | 135/10 | 135/11 | 135/12 | |||

| 2016 | 136/1 & 2 | 136/3 | 136/4 | 136/5 | 136/6 | 136/7 & 8 | 136/9 | 136/10 | 136/11 | 136/12 | |||

| 2017 | 137/1 & 2 | 137/3 & 4 | 137/5 & 6 | 137/7 & 8 | 137/9 & 10 | 137/11 & 12 | |||||||

| 2018 | 138/1 & 2 | 138/3 & 4 | 138/5 & 6 | 138/7 & 8 | 138/9 & 10 | 138/11 & 12 | |||||||

| 2019 | 139/1 & 2 | 139/3 & 4 | 139/5 & 6 | 139/7 & 8 | |||||||||

| Issues of Astounding from 1984 to 2019, showing volume and issue number. The editors were Stanley Schmidt (green) and Trevor Quachri (yellow). | |||||||||||||

In 1992 Analog was sold to Dell Magazines, and Dell was in turn acquired by Crosstown Publications in 1996.[30] That year the Mid-December issues stopped appearing, and the following year the July and August issues were combined into a single bimonthly issue.[30] An ebook edition became available in 2000 and has become increasingly popular, with the ebook numbers not reflected in the published annual circulation numbers,[30] which by 2011 were down to under 27,000.[35] In 2004 the January and February issues were combined, so that only ten issues a year appeared. Having just surpassed John W. Campbell's tenure of 34 years, Schmidt retired in August 2012. His place was taken by Trevor Quachri, who continues to edit Analog as of 2023.[30][36] From January 2017, the publication frequency became bimonthly (six issues per year).[37] In February 2025, the magazine was purchased by a group of investors led by Steven Salpeter, president of literary and IP development at Assemble Media.[38][39]

Contents and reception

[edit]Bates

[edit]

The first incarnation of Astounding was an adventure-oriented magazine: unlike Gernsback, Bates had no interest in educating his readership through science. The covers were all painted by Wesso and similarly action-filled; the first issue showed a giant beetle attacking a man. Bates would not accept any experimental stories, relying mostly on formulaic plots. In the eyes of Mike Ashley, a science fiction historian, Bates was "destroying the ideals of science fiction".[40] One historically important story that almost appeared in Astounding was E.E. Smith's Triplanetary, which Bates would have published had Astounding not folded in early 1933. The cover Wesso had painted for the story appeared on the March 1933 issue, the last to be published by Clayton.[41]

Tremaine

[edit]When Street & Smith acquired Astounding, they also planned to relaunch another Clayton pulp, Strange Tales, and acquired material for it before deciding not to proceed. These stories appeared in the first Street & Smith Astounding, dated October 1933.[11] This issue and the next were unremarkable in quality, but with the December issue, Tremaine published a statement of editorial policy, calling for "thought variant" stories containing original ideas and not simply reproducing adventure themes in a science fiction context. The policy was probably worked out between Tremaine and Desmond Hall, his assistant editor, in an attempt to give Astounding a clear identity in the market that would distinguish it from both the existing science fiction magazines and the hero pulps, such as The Shadow, that frequently used sf ideas.[42]

The "thought variant" policy may have been introduced for publicity, rather than as a real attempt to define the sort of fiction Tremaine was looking for;[4] the early "thought variant" stories were not always very original or well executed.[42] Ashley describes the first, Nat Schachner's "Ancestral Voices", as "not amongst Schachner's best"; the second, "Colossus", by Donald Wandrei, was not a new idea, but was energetically written. Over the succeeding issues, it became apparent that Tremaine was genuinely willing to publish material that would have fallen foul of editorial taboos elsewhere. He serialized Charles Fort's Lo!, a nonfiction work about strange and inexplicable phenomena, in eight parts between April and November 1934, in an attempt to stimulate new ideas for stories.[42] The best-remembered story of 1934 is probably Jack Williamson's "The Legion of Space", which began serialization in April, but other notable stories include Murray Leinster's "Sidewise in Time", which was the first genre science fiction story to use the idea of alternate history;[42][43] "The Bright Illusion", by C.L. Moore, and "Twilight", by John W. Campbell, writing as Don A. Stuart. "Twilight", which was written in a more literary and poetic style than Campbell's earlier space opera stories, was particularly influential, and Tremaine encouraged other writers to produce similar stories. One such was Raymond Z. Gallun's "Old Faithful", which appeared in the December 1934 issue and was sufficiently popular that Gallun wrote a sequel, "Son of Old Faithful", published the following July.[42] Space opera continued to be popular, though, and two overlapping space opera novels were running in Astounding late in the year: The Skylark of Valeron by E.E. Smith, and The Mightiest Machine, by Campbell. By the end of the year, Astounding was the clear leader of the small field of sf magazines.[4]

Astounding's readership was more knowledgeable and more mature than the readers of the other magazines, and this was reflected in the cover artwork, almost entirely by Howard V. Brown, which was less garish than at Wonder Stories or Amazing Stories. Ashley describes the interior artwork as "entrancing, giving hints of higher technology without ignoring the human element", and singles out the work of Elliot Dold as particularly impressive.[42]

Tremaine's policy of printing material that he liked without staying too strictly within the bounds of the genre led him to serialize H.P. Lovecraft's novel At the Mountains of Madness in early 1936. He followed this with Lovecraft's "The Shadow Out of Time" in June 1936, though protests from science fiction purists occurred. Generally, however, Tremaine was unable to maintain the high standard he had set in the first few years, perhaps because his workload was high. Tremaine's slow responses to submissions discouraged new authors, although he could rely on regular contributors such as Jack Williamson, Murray Leinster, Raymond Gallun, Nat Schachner, and Frank Belknap Long. New writers who did appear during the latter half of Tremaine's tenure included Ross Rocklynne, Nelson S. Bond, and L. Sprague de Camp, whose first appearance was in September 1937 with "The Isolinguals".[44] Tremaine printed some nonfiction articles during his tenure, with Campbell providing an 18-part series on the Solar System between June 1936 and December 1937.[44]

Campbell

[edit]

Street & Smith hired Campbell in October 1937. Although he did not gain full editorial control of Astounding until the March 1938 issue, Campbell was able to introduce some new features before then. In January 1938, he began to include a short description of stories in the next issue, titled "In Times To Come"; and in March, he began "The Analytical Laboratory", which compiled votes from readers and ranked the stories in order. The payment rate at the time was one cent a word, and Street & Smith agreed to let Campbell pay a bonus of an extra quarter-cent a word to the writer whose story was voted top of the list.[44] Unlike other editors Campbell paid authors when he accepted—not published—their work; publication usually occurred several months after acceptance.[45]

Campbell wanted his writers to provide action and excitement, but he also wanted the stories to appeal to a readership that had matured over the first decade of the science fiction genre. He asked his writers to write stories that felt as though they could have been published as non-science fiction stories in a magazine of the future; a reader of the future would not need long explanations for the gadgets in their lives, so Campbell asked his writers to find ways of naturally introducing technology to their stories.[44][46] He also instituted regular nonfiction pieces, with the goal of stimulating story ideas. The main contributors of these were R.S. Richardson, L. Sprague de Camp, and Willy Ley.[44]

Campbell changed the approach to the magazine's cover art, hoping that more mature artwork would attract more adult readers and enable them to carry the magazine without embarrassment. Howard V. Brown had done almost every cover for the Street & Smith version of Astounding, and Campbell asked him to do an astronomically accurate picture of the Sun as seen from Mercury for the February 1938 issue. He also introduced Charles Schneeman as a cover artist, starting with the May 1938 issue, and Hubert Rogers in February 1939; Rogers quickly became a regular, painting all but four of the covers between September 1939 and August 1942.[44] They differentiated the magazine from rivals. Algis Budrys recalled that "Astounding was the last magazine I picked up" as a child because, without covers showing men with ray guns and women with large breasts, "it didn't look like an SF magazine".[47]

Golden Age

[edit]The period beginning with Campbell's editorship of Astounding is usually referred to as the Golden Age of Science Fiction, because of the immense influence he had on the genre. Within two years of becoming editor, he had published stories by many of the writers who would become central figures in science fiction. The list of names included established authors like L. Ron Hubbard, Clifford Simak, Jack Williamson, L. Sprague de Camp, Henry Kuttner, and C.L. Moore, who became regulars in either Astounding or its sister magazine, Unknown, and new writers who published some of their first stories in Astounding, such as Lester del Rey, Theodore Sturgeon, Isaac Asimov, A. E. van Vogt, and Robert Heinlein.[48]

The April 1938 issue included the first story by del Rey, "The Faithful", and de Camp's second sale, "Hyperpilosity".[44] Jack Williamson's "Legion of Time", described by author and editor Lin Carter as "possibly the greatest single adventure story in science fiction history",[49] began serialization in the following issue. De Camp contributed a nonfiction article, "Language for Time Travelers", in the July issue, which also contained Hubbard's first science fiction sale, "The Dangerous Dimension". Hubbard had been selling genre fiction to the pulps for several years by that time. The same issue contained Clifford Simak's "Rule 18"; Simak had more-or-less abandoned science fiction within a year after breaking into the field in 1931, but he was drawn back by Campbell's editorial approach. The next issue featured one of Campbell's best-known stories, "Who Goes There?", and included Kuttner's "The Disinherited"; Kuttner had been selling successfully to the other pulps for a few years, but this was his first story in Astounding. In October, de Camp began a popular series about an intelligent bear named Johnny Black with "The Command."[44]

The market for science fiction expanded dramatically the following year; several new magazines were launched, including Startling Stories in January 1939, Unknown in March (a fantasy companion to Astounding, also edited by Campbell), Fantastic Adventures in May, and Planet Stories in December. All of the competing magazines, including the two main extant titles, Wonder Stories and Amazing Stories, were publishing space opera, stories of interplanetary adventure, or other well-worn ideas from the early days of the genre. Campbell's attempts to make science fiction more mature led to a natural division of the writers: those who were unable to write to his standards continued to sell to other magazines; and those who could sell to Campbell quickly focused their attention on Astounding and sold relatively little to the other magazines. The expansion of the market also benefited Campbell because writers knew that if he rejected their submissions, they could resubmit those stories elsewhere; this freed them to try to write to his standards.[50]

In July 1939, the lead story was "Black Destroyer", the first sale by van Vogt; the issue also included "Trends", Asimov's first sale to Campbell and his second story to see print. Later fans identified the issue as the start of the Golden Age.[51] Other first sales that year included Heinlein's "Lifeline" in August and Sturgeon's "Ether Breather" the following month.[50] One of the most popular authors of space opera, E.E. Smith, reappeared in October, with the first installment of Gray Lensman. This was a sequel to Galactic Patrol, which had appeared in Astounding two years before.[50]

Heinlein rapidly became one of the most prolific contributors to Astounding, publishing three novels in the next two years: If This Goes On—, Sixth Column, and Methuselah's Children; and half a dozen short stories. In September 1940, van Vogt's first novel, Slan, began serialization; the book was partly inspired by a challenge Campbell laid down to van Vogt that it was impossible to tell a superman story from the point of view of the superman. It proved to be one of the most popular stories Campbell published, and is an example of the way Campbell worked with his writers to feed them ideas and generate the material he wanted to buy. Isaac Asimov's "Robot" series began to take shape in 1941, with "Reason" and "Liar!" appearing in the April and May issues; as with "Slan", these stories were partly inspired by conversations with Campbell.[50] Van Vogt's "The Seesaw", in the July 1941 issue, was the first story in his "Weapon Shop" series, described by critic John Clute as the most compelling of all van Vogt's work.[52] The September 1941 issue included Asimov's short story "Nightfall"[53] and in November, Second Stage Lensman, the next novel in Smith's Lensman series, began serialization.[50]

The following year brought the first installment of Asimov's "Foundation" stories; "Foundation" appeared in May and "Bridle and Saddle" in June.[50] The March 1942 issue included Van Vogt's novella "Recruiting Station", an early version of a Changewar.[52] Henry Kuttner and C.L. Moore began to appear regularly in Astounding, often under the pseudonym "Lewis Padgett", and more new writers appeared: Hal Clement, Raymond F. Jones, and George O. Smith, all of whom became regular contributors. The September 1942 issue contained del Rey's "Nerves", which was one of the few stories to be ranked top by every single reader who voted in the monthly Analytical Laboratory poll; it dealt with the aftermath of an explosion at a nuclear plant.[50]

Campbell emphasized scientific accuracy over literary style. Asimov, Heinlein, and de Camp were trained scientists and engineers.[54] After 1942, several of the regular contributors such as Heinlein, Asimov, and Hubbard, who had joined the war effort, appeared less frequently. Among those who remained, the key figures were van Vogt, Simak, Kuttner, Moore, and Fritz Leiber, all of whom were less oriented towards technology in their fiction than writers like Asimov or Heinlein. This led to the appearance of more psychologically oriented fiction, such as van Vogt's World of Null-A, which was serialized in 1945. Kuttner and Moore contributed a humorous series about an inventor, Galloway Gallegher, who could only invent while drunk, but they were also capable of serious fiction.[55] Campbell had asked them to write science fiction with the same freedom from constraints that he had allowed them in the fantasy works they were writing for Unknown, Street & Smith's fantasy title; the result was "Mimsy Were the Borogoves", which appeared in February 1943 and is now regarded as a classic.[55][notes 1] Leiber's Gather, Darkness!, serialized in 1943, was set in a world where scientific knowledge is hidden from the masses and presented as magic; as with Kuttner and Moore, he was simultaneously publishing fantasies in Unknown.[55]

Campbell continued to publish technological sf alongside the soft science fiction. One example was Cleve Cartmill's "Deadline", a story about the development of the atomic bomb. It appeared in 1944, when the Manhattan Project was still not known to the public; Cartmill used his background in atomic physics to assemble a plausible story that had strong similarities to the real-world secret research program. Military Intelligence agents called on Campbell to investigate, and were satisfied when he explained how Cartmill had been able to make so many accurate guesses.[57] In the words of science fiction critic John Clute, "Cartmill's prediction made sf fans enormously proud", as some considered the story proof that science fiction could be predictive of the future.[58]

Post-war years

[edit]In the late 1940s, both Thrilling Wonder and Startling Stories began to publish much more mature fiction than they had during the war, and although Astounding was still the leading magazine in the field, it was no longer the only market for the writers who had been regularly selling to Campbell. Many of the best new writers still broke into print in Astounding rather than elsewhere. Arthur C. Clarke's first story, "Loophole", appeared in the April 1946 Astounding, and another British writer, Christopher Youd, began his career with "Christmas Tree" in February 1949. Youd would become much better known under his pseudonym "John Christopher". William Tenn's first sale, "Alexander the Bait", appeared in May 1946, and H. Beam Piper's "Time and Time Again" in the April 1947 issue was his first story. Along with these newer writers, Campbell was still publishing strong material by authors who had become established during the war. Among the better-known stories of this era are "Vintage Season", by C.L. Moore (under the pseudonym Lawrence O'Donnell); Jack Williamson's story "With Folded Hands"; The Players of Null-A, van Vogt's sequel to The World of Null-A; and the final book in E.E. Smith's Lensman series, Children of the Lens.[59]

In the November 1948 issue, Campbell published a letter to the editor by a reader named Richard A. Hoen that contained a detailed ranking of the contents of an issue "one year in the future". Campbell went along with the joke and contracted stories from most of the authors mentioned in the letter that would follow the Hoen's imaginary story titles. One of the best-known stories from that issue is "Gulf", by Heinlein. Other stories and articles were written by some of the most famous authors of the time: Asimov, Sturgeon, del Rey, van Vogt, de Camp, and the astronomer R. S. Richardson.[60]

1950s and 1960s

[edit]By 1950, Campbell's strong personality had led him into conflict with some of his leading writers, some of whom abandoned Astounding as a result.[61] The launch of both The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction and Galaxy Science Fiction in 1949 and 1950, respectively, marked the end of Astounding's dominance of science fiction,[61] with many now regarding Galaxy as the leading magazine.[notes 2] Campbell's growing interest in pseudoscience also damaged his reputation in the field.[63] Campbell was deeply involved with the launch of Dianetics, publishing Hubbard's first article on it in Astounding in May 1950, and promoting it heavily in the months beforehand;[64][65] later in the decade he championed psionics and antigravity devices.[4]

Although these enthusiasms diminished Campbell's reputation, Astounding continued to publish some popular and influential science fiction.[66] In 1953, Campbell serialized Hal Clement's Mission of Gravity, described by John Clute and David Langford as "one of the best-loved novels in sf",[67] and in 1954 Tom Godwin's "The Cold Equations" appeared. The story, about a girl who stows away on a spaceship, generated much reader debate, and has been described as capturing the ethos of Campbell's Astounding.[68][69] The spaceship is carrying urgently needed medical supplies to a planet in distress, and has a single pilot; the ship does not have enough fuel to reach the planet if the girl stays on the ship, so the "cold equations" of physics force the pilot to jettison the girl, killing her.[69]

Later in the 1950s and early 1960s writers like Gordon R. Dickson, Poul Anderson, and Harry Harrison appeared regularly in the magazine.[66] Frank Herbert's Dune was serialized in Analog in two separate sequences, in 1963 and 1965, and soon became "one of the most famous of all sf novels", according to Malcolm Edwards and John Clute.[70] 1965 marked the year Campbell received his eighth Hugo Award for Best Professional Magazine; this was the last one he would win.[61]

Bova

[edit]Bova, like Campbell, was a technophile with a scientific background, and he declared early in his tenure that he wanted Analog to continue to focus on stories with a scientific foundation, though he also made it clear that change was inevitable.[71] Over his first few months some long-time readers sent in letters of complaint when they judged that Bova was not living up to Campbell's standards, particularly when sex scenes began to appear. On one occasion—Jack Wodhams' story "Foundling Fathers", and its accompanying illustration by Kelly Freas—it turned out that Campbell had bought the story in question. As the 1970s went on, Bova continued to publish authors such as Anderson, Dickson, and Christopher Anvil, who had appeared regularly during Campbell's tenure, but he also attracted authors who had not been able to sell to Campbell, such as Gene Wolfe, Roger Zelazny, and Harlan Ellison.[72] Frederik Pohl, who later commented in his autobiography about his difficulties in selling to Campbell, appeared in the March 1972 issue with "The Gold at the Starbow's End", which was nominated for both the Hugo and Nebula Awards, and that summer Joe Haldeman's "Hero" appeared. This was the first story in Haldeman's "Forever War" sequence; Campbell had rejected it, listing multiple reasons including the frequent use of profanity and the implausibility of men and women serving in combat together. Bova asked to see it again and ran it without asking for changes.[73] Other new writers included Spider Robinson, whose first sale was "The Guy With the Eyes" in the February 1973 issue; George R.R. Martin, with "A Song for Lya", in June 1974; and Orson Scott Card, with "Ender's Game", in the August 1977 issue.[72][73]

Two of the cover artists who had been regular contributors under Campbell, Kelly Freas and John Schoenherr, continued to appear after Bova took over, and Bova also began to regularly feature covers by Rick Sternbach and Vincent Di Fate. Jack Gaughan, who had had a poor relationship with Campbell, sold several covers to Bova.[74][75] Bova won the Hugo Award for Best Professional Editor for five consecutive years, 1973 through 1977.[76]

Schmidt

[edit]Stanley Schmidt was an assistant professor of physics when he became editor of Analog, and his scientific background was well-suited to the magazine's readership. He avoided making drastic changes, and continued the long-standing tradition of writing provocative editorials, though he rarely discussed science fiction.[notes 3] In 1979 he resurrected "Probability Zero", a feature that Campbell had run in the early 1940s that published tall tales—humorous stories with ludicrous or impossible scientific premises. Also in 1979 Schmidt began a series of columns titled "The Alternate View", an opinion column that was written in alternate issues by G. Harry Stine and Jerry Pournelle, and which is still a feature of the magazine as of 2016, though now with different contributors.[30][77][78] The stable of fiction contributors remained largely unchanged from Bova's day, and included many names, such as Poul Anderson, Gordon R. Dickson, and George O. Smith, familiar to readers from the Campbell era. This continuity led to criticisms within the field, Bruce Sterling writing in 1984 that the magazine "has become old, dull, and drivelling... It is a situation screaming for reform. Analog no longer permits itself to be read." The magazine thrived nevertheless, and though part of the increase in circulation during the early 1980s may have been due to Davis Publications' energetic efforts to increase subscriptions, Schmidt knew what his readership wanted and made sure they got it, commenting in 1985: "I reserve Analog for the kind of science fiction I've described here: good stories about people with problems in which some piece of plausible (or at least not demonstrably implausible) speculative science plays an indispensable role".[79]

Over the decades of Schmidt's editorship, many writers became regular contributors, including Arlan Andrews, Catherine Asaro, Maya Kaathryn Bohnhoff, Michael Flynn, Geoffrey A. Landis, Paul Levinson, Robert J. Sawyer, Charles Sheffield and Harry Turtledove. Schmidt never won an editing Hugo while in charge of the magazine, but after he resigned he won the 2013 Hugo for Editor Short Form.[30]

Quachri

[edit]Schmidt retired in August 2012, and his place was taken by Trevor Quachri,[30] who mostly continued the editorial policies of Schmidt. Starting in January 2017, the publication became bimonthly.[37] In 2025, the magazine introduced "Unknowns," a puzzle column edited by Alec Nevala-Lee, that featured "science-fictional puzzles from notable constructors."[80]

Bibliographic details

[edit]Editorial history at Astounding and Analog:[30]

- Harry Bates, January 1930 – March 1933

- F. Orlin Tremaine, October 1933 – October 1937

- John W. Campbell, Jr., October 1937 – December 1971

- Ben Bova, January 1972 – November 1978

- Stanley Schmidt, December 1978 – August 2012

- Trevor Quachri, September 2012 – present

Astounding was published in pulp format until the January 1942 issue, when it switched to bedsheet. It reverted to pulp for six issues, starting in May 1943, and then became the first of the genre sf magazines to be published in digest format, beginning with the November 1943 issue. The format remained unchanged until Condé Nast produced 25 bedsheet issues of Analog between March 1963 and March 1965, after which it returned to digest format.[81] In May 1998, and again in December 2008, the format was changed to be slightly larger than the usual digest size: first to 8.25 x 5.25 in (210 x 135 mm), and then to 8.5 x 5.75 in (217 x 148 mm).[30]

The magazine was originally titled Astounding Stories of Super-Science; this was shortened to Astounding Stories from February 1931 to November 1932, and the longer title returned for the three Clayton issues at the start of 1933. The Street & Smith issues began as Astounding Stories, and changed to Astounding Science-Fiction in March 1938. The hyphen disappeared in November 1946, and the title then remained unchanged until 1960, when the title Analog Science Fact & Fiction was phased in between February and October (i.e., the words "Astounding" and "Analog" both appeared on the cover, with "Analog" gradually increasing in prominence over the months, culminating in the name "Astounding" being completely dropped.) In April 1965 the subtitle was reversed, so that the magazine became Analog Science Fiction & Fact, and it has remained unchanged since then, though it has undergone several stylistic and orthographic variations.[30][81]

As of 2016, the sequence of prices over the magazine's history is as follows:[7][81]

| Price history | |

|---|---|

| Issues | Price |

| January 1930 – December 1941 | 20 cents |

| January 1942 – July 1951 | 25 cents |

| August 1951 – October 1959 | 35 cents |

| November 1959 – July 1966 | 50 cents |

| August 1966 – June 1974 | 60 cents |

| July 1974 – February 1975 | 75 cents |

| March 1975 – March 1977 | $1.00 |

| April 1977 – March 1980 | $1.25 |

| April 1981 – November 1982 | $1.50 |

| December 1982 – December 1984 | $1.75 |

| Mid-December 1984 – Mid-December 1989 | $2.00 |

| January 1990 – Mid-December 1990 | $3.95 for the January issue; $2.50 for other issues |

| January 1991 – October 1993 | $3.95 for the January and July issues; $2.50 for other issues |

| November 1993 – June 1995 | $3.95 for the January and July issues; $2.95 for other issues |

| July 1995 – December 1996 | $4.50 for the January and July issues; $2.95 for other issues |

| January 1997 – May 1999 | $4.50 for the July/August issue; $2.95 for other issues |

| June 1999 – December 2000 | $4.50 for the January issue; $5.50 for the July/August issue; $3.50 for other issues |

| January 2001 – July/August 2003 | $5.50 for the July/August issue; $3.50 for other issues |

| September 2003 – March 2008 | $5.99 for the July/August issue; $3.99 for other issues |

| April 2008 – September 2016 | $7.99 for the January/February and July/August issues; $4.99 for other issues |

Circulation figures

[edit]| Year | Number of Copies |

|---|---|

| 1926 | 100,000 |

| 1934 | 50,000 |

| 1981 | 92,000 |

| 1983 | 110,000 |

| 1990 | 83,000 |

| 2011 | 27,000 |

Overseas editions

[edit]| Issue data for British edition | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

| 1939 | 23/6 | 24/1 | 24/2 | 24/3 | 24/4 | |||||||

| 1940 | 24/5 | 24/6 | 25/1 | 25/2 | 25/3 | 25/4 | 25/5 | 25/6 | 26/1 | 26/2 | 26/3 | 26/4 |

| 1941 | 26/5 | 26/6 | 27/1 | 27/2 | 27/4 | 27/5 | 27/6 | 28/1 | 28/3 | 28/4 | ||

| 1942 | 28/5 | 28/6 | 29/3 | 29/4 | 30/1 | |||||||

| 1943 | 30/2 | 30/4 | 31/1 | nn | nn | nn | ||||||

| 1944 | nn | nn | nn | nn | nn | nn | ||||||

| 1945 | 4/9 | 4/10 | 4/11 | 4/12 | 5/1 | |||||||

| 1946 | 5/2 | 5/3 | 5/4 | 5/5 | 5/6 | 5/7 | ||||||

| 1947 | 5/8 | 5/9 | 5/10 | 5/11 | 5/12 | 6/1 | ||||||

| 1948 | 6/2 | 6/3 | 6/4 | 6/5 | 6/6 | 6/7 | ||||||

| 1949 | 6/8 | 6/9 | 6/10 | 6/11 | 6/12 | |||||||

| 1950 | 7/1 | 7/2 | 7/3 | 7/4 | 7/5 | 7/6 | 7/7 | |||||

| 1951 | 7/8 | 7/9 | 7/10 | 7/11 | 7/12 | 8/1 | ||||||

| 1952 | 8/2 | 8/3 | 8/4 | 8/5 | 8/6 | 8/7 | 8/8 | 8/9 | 8/10 | 8/11 | 8/12 | |

| 1953 | 9/1 | 9/2 | 9/3 | 9/4 | 9/5 | 9/6 | 9/7 | 9/8 | 9/9 | 9/10 | 9/11 | 9/12 |

| 1954 | 10/1 | 10/2 | 10/3 | 10/4 | 10/5 | 10/6 | 10/7 | 10/8 | 10/9 | 10/10 | 10/11 | 10/12 |

| 1955 | 11/1 | 11/2 | 11/3 | 11/4 | 11/5 | 11/6 | 11/7 | 11/8 | 11/9 | 11/10 | 11/11 | 11/12 |

| 1956 | 12/1 | 12/2 | 12/3 | 12/4 | 12/5 | 12/6 | 12/7 | 12/8 | 12/9 | 12/10 | 12/11 | 12/12 |

| 1957 | 13/1 | 13/2 | 13/3 | 13/4 | 13/5 | 13/6 | 13/7 | 13/8 | 13/9 | 13/10 | 13/11 | 13/12 |

| 1958 | 14/1 | 14/2 | 14/3 | 14/4 | 14/5 | 14/6 | 14/7 | 14/8 | 14/9 | 14/10 | 14/11 | 14/12 |

| 1959 | 15/1 | 15/2 | 15/3 | 15/4 | 15/5 | 15/6 | 15/7 | 15/8 | 15/9 | 15/10 | ||

| 1960 | 15/11 | 15/12 | 16/1 | 16/2 | 16/3 | 16/4 | 16/5 | 16/6 | 16/7 | 16/8 | 16/9 | 16/10 |

| 1961 | 17/1 | 17/2 | 17/3 | 17/4 | 17/5 | 17/6 | 17/7 | 17/8 | 17/9 | 17/10 | 17/11 | 17/12 |

| 1962 | 18/1 | 18/2 | 18/3 | 18/4 | 18/5 | 18/6 | 18/7 | 18/8 | 18/9 | 18/10 | 18/11 | 18/12 |

| 1963 | 19/1 | 19/2 | 19/3 | 19/4 | 19/5 | 19/6 | 19/7 | 19/8 | ||||

| Issues of Astounding Stories, showing volume/issue number; "nn" indicates that the issue had no number.[82][83] | ||||||||||||

A British edition published by Atlas Publishing and Distributing Company ran from August 1939 until August 1963, initially in pulp format, switching to digest from November 1953. The pulp issues began at 96 pages, then dropped to 80 pages with the March 1940 issue, and to 64 pages in December that year. All the digest issues were 128 pages long. The price was 9d until October 1953; thereafter it was 1/6 until February 1961, and 2/6 until the end of the run. The material in the British editions was selected from the U.S. issues, most stories coming from a single U.S. number, and other stories picked from earlier or later issues to fill the magazine.[83] The covers were usually repainted from the American originals.[84]

An Italian magazine, Scienza Fantastica [it], published seven issues from April 1952 to March 1953, the contents drawn mostly from Astounding, along with some original stories. The editor was Lionello Torossi [it], and the publisher was Editrice Krator.[85] Another Italian edition, called Analog Fantascienza, was published by Phoenix Enterprise in 1994/1995, for a total of five issues.[86] Danish publisher Skrifola produced six issues of Planetmagazinet in 1958; it carried reprints, mostly from Astounding, and was edited by Knud Erik Andersen.[87]

A German anthology series of recent 1980s stories from Analog was published in eight volumes by Pabel-Moewig Verlag [de] from October 1981 up to June 1984.[88]

Anthologies

[edit]Anthologies of stories from Astounding or Analog include:[4][30][83]

| Year | Editor | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1952 | John W. Campbell | The Astounding Science Fiction Anthology | |

| 1962 | John W. Campbell | Prologue to Analog | |

| 1963–1971 | John W. Campbell, Ben Bova | Analog 1 through Analog 9 | Issued yearly, 1963–1968, then 1970 and 1971. The first eight volumes were edited by Campbell; the ninth by Bova. |

| 1972–1973 | Harry Harrison & Brian W. Aldiss | The Astounding–Analog Reader Volume 1 | Two volumes, issued in 1972 and 1973. |

| 1978 | Ben Bova | The Best of Analog | |

| 1978 | Tony Lewis | The Best of Astounding | |

| 1980–1984 | Stanley Schmidt | The Analog Anthologies | Ten volumes. |

| 1981 | Martin H. Greenberg | Astounding | Facsimile of the July 1939 issue, with some additional commentary. |

| 2010 | G.W. Thomas | Vagabonds of Space | These four anthologies are drawn from the Clayton era, and have the running title The Clayton Astounding Stories. |

| 2010 | G.W. Thomas | Out of the Dreadful Depths | |

| 2010 | G.W. Thomas | Planetoids of Peril | |

| 2010 | G.W. Thomas | Invasion Earth! | |

| 2011 | Stanley Schmidt | Into the New Millennium: Trailblazing Tales From Analog Science Fiction and Fact, 2000–2010 | This title was published strictly as an ebook, without any physical print editions. |

Notes

[edit]- ^ For example, Malcolm Edwards and Brian Stableford describe the story as a "classic",[56] and Ashley describes it as "a brilliant story merging the wonders of the unknown with its horrors".[50]

- ^ For example, Isaac Asimov, in his memoirs, recalls that many fans, including himself, felt that Galaxy became the field's leader almost immediately.[62]

- ^ Typical themes for his editorials included scientific rapport, how to make the draft more equitable, and the distinction between a science crackpot and a genuine unrecognized genius.[77]

References

[edit]- ^ Ashley (2000), p. 48.

- ^ Ashley (2000), p. 69. The quote is from Hersey (1937), p. 188, cited by Ashley.

- ^ a b Ashley (2000), p. 69.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Edwards, Malcolm; Nicholls, Peter; Ashley, Mike. "Culture : Astounding Science-Fiction : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- ^ Ashley (2000), p. 239.

- ^ Ashley (2007), p. 425.

- ^ a b c d e See the individual issues. For convenience, an online index is available at "Magazine: Astounding Science Fiction – ISFDB". Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved June 26, 2008. and "Magazine: Analog Science Fiction and Fact – ISFDB". Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on January 13, 2022. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- ^ "Corporate Changes". The New York Times. March 28, 1931. "Publishers Fiscal Corp., Manhattan, to Clayton Magazines."

- ^ a b Ashley (2000), p. 72.

- ^ Ashley (2000), pp. 76–77.

- ^ a b Ashley (2000), p. 82.

- ^ Ashley (2004), p. 204.

- ^ Joshi, Schultz, Derleth & Lovecraft (2008), pp. 599–601.

- ^ Ashley (2000), pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b Ashley (2000), p. 84.

- ^ Ashley (2000), p. 85. The estimate is Ashley's.

- ^ Ashley (2000), pp. 85–87.

- ^ Ashley (2000), p. 105.

- ^ Quoted in Ashley (2000), p. 105.

- ^ Ashley (2000), pp. 105–106.

- ^ Ashley (2000), pp. 86–87.

- ^ Ashley (2000), p. 107.

- ^ a b Ashley (2000), p. 108.

- ^ Ashley (2000), p. 158.

- ^ Towles Canote, Terence (June 29, 2008). "Should Analog Become Astounding?". A Shroud of Thoughts. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ Ashley (2005), pp. 201–202.

- ^ Ashley (2005), p. 202.

- ^ Ashley (2016), p. 448.

- ^ Ashley (2005), p. 213.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Culture : Analog : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". www.sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- ^ Ashley (2007), p. 6.

- ^ a b Ashley (2007), pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b Ashley (2007), pp. 341–346.

- ^ a b Ashley (2016), pp. 58–59.

- ^ "2011 Magazine Summary". Locus. February 2012. pp. 56–7.

- ^ "From the Editor". Analog Science Fiction and Fact. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ^ a b "Locus". November 16, 2016. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- ^ "New Ownership for Asimov's, Analog and F&SF". February 26, 2025.

- ^ "Analog, Asimov's, and F&SF Under New Ownership". February 26, 2025.

- ^ Ashley (2000), pp. 69–70, 72.

- ^ Ashley (2000), p. 77.

- ^ a b c d e f Ashley (2000), pp. 84–87.

- ^ Stableford, Brian M.; Wolfe, Gary K.; Langford, David. "Themes : Alternate History : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ashley (2000), pp. 106–111.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1972). The early Asimov; or, Eleven years of trying. Garden City NY: Doubleday. pp. 25–28.

- ^ Pohl, Frederik (October 1965). "The Day After Tomorrow". Editorial. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 4–7.

- ^ Pontin, Mark Williams (October 20, 2008). "The Alien Novelist". MIT Technology Review.

- ^ Nicholls, Peter; Ashley, Mike. "Themes : Golden Age of SF : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ Williamson (1977), back cover.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ashley (2000), pp. 153–158.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1972). The early Asimov; or, Eleven years of trying. Garden City NY: Doubleday. pp. 79–82.

- ^ a b Clute, John. "Authors : van Vogt, A E : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ Clute, John; Edwards, Malcolm. "Authors : Asimov, Isaac : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ Latham, Rob (2009). "Fiction, 1950-1963". In Bould, Mark; Butler, Andrew M.; Roberts, Adam; Vint, Sherryl (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Science Fiction. Routledge. pp. 80–89. ISBN 978-1135228361.

- ^ a b c Ashley (2000), pp. 169–174.

- ^ Edwards, Malcolm; Stableford, Brian; Clute, John. "Authors : Kuttner, Henry : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ Aldiss & Wingrove (1986), p. 224.

- ^ "Authors : Cartmill, Cleve : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- ^ Ashley (2000), pp. 190–193.

- ^ Rogers (1970), pp. 176–180.

- ^ a b c Edwards, Malcolm; Clute, John. "Authors : Campbell, John W, Jr : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". www.sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ Asimov, In Memory Yet Green, p. 602.

- ^ Mike Ashley, "Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact", in Gunn, Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Ashley (2000), pp. 226–227.

- ^ Menadue, Christopher Benjamin (2018). "Hubbard Bubble, Dianetics Trouble: An Evaluation of the Representations of Dianetics and Scientology in Science Fiction Magazines From 1949 to 1999" (PDF). SAGE Open. 8 (4): 215824401880757. doi:10.1177/2158244018807572. ISSN 2158-2440. S2CID 149743140.

- ^ a b Berger (1985), pp. 80–81.

- ^ "Authors : Clement, Hal : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". www.sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- ^ Berger (1985), p. 82.

- ^ a b Ashley (2005), pp. 128–129.

- ^ "Authors : Herbert, Frank : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". www.sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- ^ Ashley (1985), pp. 89–90.

- ^ a b Ashley (1985), p. 90–91.

- ^ a b Ashley (2007), pp. 18–20.

- ^ Ashley (1985), p. 92.

- ^ Ashley (2007), pp. 28–29.

- ^ Ashley (2007), pp. 33–34.

- ^ a b Ashley (2016), pp. 56–58.

- ^ "Series: The Alternate View". www.isfdb.org. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- ^ Ashley (2016), pp. 56–60.

- ^ "Year-in-Review: 2024 Magazine Summary". Locus Online. February 13, 2025. Retrieved February 14, 2025.

- ^ a b c Berger & Ashley (1985), pp. 102–103.

- ^ Stephensen-Payne, Phil. "Astounding/Analog". www.philsp.com. Galactic Central. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- ^ a b c Berger & Ashley (1985), pp. 99–102.

- ^ Stone (1977), p. 19.

- ^ Montanari & de Turris (1985), pp. 881–882.

- ^ "Analog Fantascienza (Phoenix Enterprise Publishing Company)". Catalogo Vegetti della letteratura fantastica. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ^ Remar & Schiøler (1985), p. 856.

- ^ "Series: Analog (German anthologies)". ISFDB. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

Sources

[edit]- Aldiss, Brian W.; Wingrove, David (1986). Trillion Year Spree: The History of Science Fiction. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd. ISBN 0-575-03943-4.

- Ashley, Mike (1985). "Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact: IV: The Post-Campbell Years". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike (eds.). Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 88–96. ISBN 0-313-21221-X.

- Ashley, Mike (2000). The Time Machines: The Story of the Science-Fiction Pulp Magazines from the Beginning to 1950. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-865-0.

- Ashley, Mike (2004). "The Gernsback Days". In Ashley, Mike; Lowndes, Robert A.W. (eds.). The Gernsback Days: A Study of the Evolution of Modern Science Fiction from 1911 to 1936. Holicong, Pennsylvania: Wildside Press. pp. 16–254. ISBN 0-8095-1055-3.

- Ashley, Mike (2005). Transformations: The Story of the Science-Fiction Magazines from 1950 to 1970. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-779-4.

- Ashley, Mike (2007). Gateways to Forever: The Story of the Science-Fiction Magazines from 1970 to 1980. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-84631-003-4.

- Ashley, Mike (2016). Science Fiction Rebels: The Story of the Science-Fiction Magazines from 1981 to 1990. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-78138-260-8.

- Berger, Albert I. (1985). "Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact: Parts I–III". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike (eds.). Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 60–88. ISBN 0-313-21221-X.

- Berger, Albert I.; Ashley, Mike (1985). "Information Sources & Publication History". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike (eds.). Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 99–103. ISBN 0-313-21221-X.

- Hersey, Harold (1937). Pulpwood Editor. New York: F.A. Stokes. OCLC 2770489.

- Joshi, S.T.; Schultz, David E.; Derleth, August; Lovecraft, H.P. (2008). Essential Solitude: The Letters of H.P. Lovecraft and August Derleth. New York: Hippocampus Press. ISBN 978-0-9793806-4-8.

- Rogers, Alva (1970). A Requiem for Astounding. Chicago: Advent. ISBN 0911682082.

- Remar, Frits; Schiøler, Carsten (1985). "Denmark". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike (eds.). Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 855–856. ISBN 0-313-21221-X.

- Montanari, Gianni; de Turres, Gianfranco (1985). "Italy". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike (eds.). Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 872–884. ISBN 0-313-21221-X.

- Williamson, Jack (1977). The Legion of Time. London: Sphere. ISBN 0-7221-9175-8.

External links

[edit]- Analog Science Fiction and Fact official web site

- Astounding/Analog bibliography at ISFDB

- "Collection: Astounding Stories / Analog | Georgia Tech Archives Finding Aids". finding-aids.library.gatech.edu.

Public domain texts

[edit]- First year (1930) of Astounding at the Internet Archive

- Second year (1931) of Astounding at the Internet Archive

- Third year (1932) of Astounding at the Internet Archive

- First two issues of 1933 of Astounding at the Internet Archive

- Astounding Stories Bookshelf at Project Gutenberg

Astounding Stories public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Astounding Stories public domain audiobook at LibriVox- The Pulp Magazines Project