Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sampling (music)

View on Wikipedia

In sound and music, sampling is the reuse of a portion (or sample) of a sound recording in another recording. Samples may comprise elements such as rhythm, melody, speech, or sound effects. A sample might comprise only a fragment of sound, or a longer portion of music, such as a drum beat or melody. Samples are often layered, equalized, sped up or slowed down, repitched, looped, or otherwise manipulated. They are usually integrated using electronic music instruments (samplers) or software such as digital audio workstations.

A process similar to sampling originated in the 1940s with musique concrète, experimental music created by splicing and looping tape. The mid-20th century saw the introduction of keyboard instruments that played sounds recorded on tape, such as the Mellotron. The term sampling was coined in the late 1970s by the creators of the Fairlight CMI, a synthesizer with the ability to record and playback short sounds. As technology improved, cheaper standalone samplers with more memory emerged, such as the E-mu Emulator, Akai S950 and Akai MPC.

Sampling is a foundation of hip-hop, which emerged when producers in the 1980s began sampling funk and soul records, particularly drum breaks. It has influenced many other genres of music, particularly electronic music and pop. Samples such as the Amen break, the "Funky Drummer" drum break and the orchestra hit have been used in thousands of recordings, and James Brown, Loleatta Holloway, Fab Five Freddy and Led Zeppelin are among the most sampled artists. The first album created entirely from samples, Endtroducing by DJ Shadow, was released in 1996.

Sampling without permission can infringe copyright or may be fair use. Clearance, the process of acquiring permission to use a sample, can be complex and costly; samples from well-known sources may be prohibitively expensive. Courts have taken different positions on whether sampling without permission is permitted. In Grand Upright Music, Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records Inc (1991) and Bridgeport Music, Inc. v. Dimension Films (2005), American courts ruled that unlicensed sampling, however minimal, constitutes copyright infringement. However, VMG Salsoul v Ciccone (2016) found that unlicensed samples constituted de minimis copying, and did not infringe copyright. In 2019, the European Court of Justice ruled that modified, unrecognizable samples could be used without authorization. Though some artists sampled by others have complained of plagiarism or lack of creativity, many commentators have argued that sampling is a creative act.

Precursors

[edit]

In the 1940s, the French composer Pierre Schaeffer developed musique concrète, an experimental form of music created by recording sounds to tape, splicing them, and manipulating them to create sound collages. He used sounds from the human body, locomotives, and kitchen utensils. The method also involved tape loops, splicing lengths of tape end to end so a sound could be played indefinitely. Schaeffer developed the Phonogene, which played loops at 12 different pitches triggered by a keyboard.[1]

Composers including Pierre Henry, Karheinz Stockhausen, John Cage, Edgar Varèse, and Iannis Xenakis experimented with musique concrète. In the UK, it was brought to a mainstream audience by the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, which used the techniques to produce soundtracks for shows including Doctor Who in the early 1960s.[1]

In the 1960s, Jamaican dub reggae producers such as King Tubby and Lee "Scratch" Perry began using recordings of reggae rhythms to produce riddim tracks, which were then deejayed over.[2][3] Jamaican immigrants introduced the techniques to American hip-hop in the 1970s.[3] Holger Czukay of the experimental German band Can spliced tape recordings into his music before the advent of digital sampling.[4]

Techniques and tools

[edit]Samplers

[edit]

The Guardian described the Chamberlin as the first sampler, developed by the American engineer Harry Chamberlin in the 1940s. The Chamberlin used a keyboard to trigger a series of tape decks, each containing eight seconds of sound. Similar technology was popularised in the 60s with the Mellotron. In 1969, the English engineer Peter Zinovieff developed the first digital sampler, the EMS Musys.[5]

The term sample was coined by Kim Ryrie and Peter Vogel to describe a feature of their Fairlight CMI synthesizer, launched in 1979.[1] While developing the Fairlight, Vogel recorded around a second of piano performance from a radio broadcast and discovered that he could imitate a piano by playing the recording back at different pitches. The result better resembled a real piano than sounds generated by synthesizers.[6] Compared to later samplers, the Fairlight was limited; it allowed control over pitch and envelope, and could only record a few seconds of sound. However, the sampling function became its most popular feature. Though the concept of reusing recordings in other recordings was not new, the Fairlight's design and built-in sequencer simplified the process.[1]

The Fairlight inspired competition, improving sampling technology and driving down prices. Early competitors included the E-mu Emulator[1] and the Akai S950.[7] Drum machines such as the Oberheim DMX and Linn LM-1 incorporated samples of drum kits and percussion rather than generating sounds from circuits.[8] Early samplers could store samples of only a few seconds in length, but this increased with improved memory.[9] In 1988, Akai released the first MPC sampler,[10] which allowed users to assign samples to pads and trigger them independently, similarly to playing a keyboard or drum kit.[11] It was followed by competing samplers from companies including Korg, Roland and Casio.[12]

Today, most samples are recorded and edited using digital audio workstations (DAWs) such as Pro Tools and Ableton Live.[9][13] As technology has improved, the possibilities for manipulation have grown.[14]

Sample libraries

[edit]Samples are distributed in sample libraries, also known as sample packs. In the 1990s, sample libraries from companies such as Zero-G and Spectrasonics were widely used in contemporary music.[15] In the 2000s, Apple introduced "Jam Pack" sample libraries for its DAW GarageBand.[16] In the 2010s, producers began releasing sample packs on online platforms such as Splice.[17]

The Kingsway Music Library, created in 2015 by the American producer Frank Dukes,[18] has been used by artists including Drake, Kanye West, Kendrick Lamar, and J. Cole.[19][20] In 2020, the US Library of Congress created an open-source web application that allows users to sample its library of copyright-free audio.[21]

Interpolation

[edit]Instead of sampling, artists may recreate a recording, a process known as interpolation.[22] This requires only the permission of the owners of the musical content, rather than the owners of the recording. It also creates more freedom to alter constituent components such as separate guitar and drum tracks.[23]

Impact

[edit]Sampling has influenced many genres of music,[5] particularly pop, hip-hop and electronic music.[14] The Guardian journalist David McNamee likened its importance in these genres to the importance of the guitar in rock.[5] In August 2022, the Guardian noted that half of the singles in the UK Top 10 that week used samples.[22] Sampling is a fundamental element of remix culture.[24]

Early works

[edit]Using the Fairlight, the "first truly world-changing sampler", the English producer Trevor Horn became the "key architect" in incorporating sampling into pop music in the 1980s.[5] Other users of the Fairlight included Kate Bush, Peter Gabriel and Thomas Dolby.[7] In the 1980s, samples were incorporated into synthesizers and music workstations, such as the bestselling Korg M1, released in 1988.[12]

The Akai MPC, released in 1988, had a major influence on electronic and hip-hop music,[25][11] allowing artists to create elaborate tracks without other instruments, a studio or formal music knowledge.[11] Its designer, Roger Linn, anticipated that users would sample short sounds, such as individual notes or drum hits, to use as building blocks for compositions; however, users sampled longer passages of music.[9] In the words of Greg Milner, author of Perfecting Sound Forever, musicians "didn't just want the sound of John Bonham's kick drum, they wanted to loop and repeat the whole of 'When the Levee Breaks'."[9] Linn said: "It was a very pleasant surprise. After 60 years of recording, there are so many prerecorded examples to sample from. Why reinvent the wheel?"[9]

Stevie Wonder's 1979 album Journey Through the Secret Life of Plants may have been the first album to make extensive use of samples.[5] The Japanese electronic band Yellow Magic Orchestra were pioneers in sampling,[26][27][28] constructing music by cutting fragments of sounds and looping them.[28] Their album Technodelic (1981) is an early example of an album consisting mostly of samples.[27][29] My Life in the Bush of Ghosts (1981) by David Byrne and Brian Eno is another important early work of sampling, incorporating samples of sources including Arabic singers, radio DJs and an exorcist.[30] Musicians had used similar techniques before, but, according to the Guardian writer Dave Simpson, sampling had never before been used "to such cataclysmic effect".[31] Eno felt the album's innovation was to make samples "the lead vocal".[32] Big Audio Dynamite pioneered sampling in rock and pop with their 1985 album This Is Big Audio Dynamite.[33]

Hip-hop

[edit]

Sampling is one of the foundations of hip-hop, which emerged in the 1980s.[34] Hip-hop sampling has been likened to the origins of blues and rock, which were created by repurposing existing music.[24] The Guardian journalist David McNamee wrote that "two record decks and your dad's old funk collection was once the working-class black answer to punk".[13]

Before the rise of sampling, DJs used turntables to loop breaks from records, which MCs would rap over. Compilation albums such as Ultimate Breaks and Beats compiled tracks with drum breaks and solos intended for sampling, aimed at DJs and hip-hop producers.[35] In 1986, the tracks "South Bronx", "Eric B. is President" and "It's a Demo" sampled the funk and soul tracks of James Brown, particularly a drum break from "Funky Drummer" (1970), helping popularize the technique.[14]

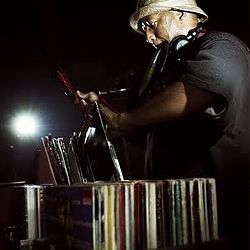

The advent of affordable samplers such as the Akai MPC (1988) made looping easier.[35] Guinness World Records cites DJ Shadow's acclaimed hip-hop album Endtroducing (1996), made on an MPC60,[36] as the first album created entirely from samples.[37][38] The E-mu SP-1200, released in 1987, had a ten-second sample length and a distinctive "gritty" sound, and was used extensively by East Coast producers during the golden age of hip-hop of the late 1980s and early 90s.[39]

Common samples

[edit]Commonly sampled elements include strings, basslines, drum loops, vocal hooks or entire bars of music, especially from soul records.[40] Samples may be layered, equalized,[41] sped up or slowed down, repitched, looped or otherwise manipulated.[14]

A seven-second drum break in the 1969 track "Amen, Brother", known as the Amen break, became popular with American hip-hop producers and then British jungle producers in the early 1990s. It has been used in thousands of recordings, including songs by rock bands such as Oasis and theme tunes for television shows such as Futurama, and is among the most sampled tracks in music history.[35] Other widely sampled drum breaks include the break from the 1970 James Brown song "Funky Drummer"; the Think break, sampled from the 1972 Lyn Collins song "Think (About It)", written by Brown;[42] and the drum intro from Led Zeppelin's 1971 song "When the Levee Breaks", played by John Bonham and sampled by artists including the Beastie Boys, Dr. Dre, Eminem and Massive Attack.[43]

In 2014, the Smithsonian cited the most sampled track as "Change the Beat" (1982) by Fab Five Freddy.[44] According to WhoSampled, a user-edited website that catalogs samples, James Brown is sampled in more than 3000 tracks, more than any other artist.[45] In 2011, The Independent named Loleatta Holloway, whose vocals were sampled in house and dance tracks such as "Ride on Time" (1989) by Black Box, as the most sampled female singer.[46]

The orchestra hit originated as a sound on the Fairlight, sampled from Stravinsky's 1910 orchestral work Firebird Suite,[47]: 1 and became a hip-hop cliché.[48] MusicRadar cited the Zero-G Datafiles sample libraries as a major influence on 90s dance music, becoming the "de facto source of breakbeats, bass and vocal samples".[15]

Legal and ethical issues

[edit]To legally use a sample, an artist must acquire legal permission from the copyright holder, a potentially lengthy and complex process known as clearance. Sampling without permission can breach the copyright of the original sound recording, of the composition and lyrics, and of the performances, such as a rhythm or guitar riff. The moral rights of the original artist may also be breached if they are not credited or object to the sampling. In some cases, sampling is protected under American fair use laws,[40] which grant "limited use of copyrighted material without permission from the rights holder".[49] Deborah Mannis-Gardner of DMG Clearances, referring to the use of "Somebody That I Used to Know" in the Doechii song "Anxiety", said that the original recording was sampled, requiring consent from the masters rights holders rather than just the holders of publishing rights.[50]

The American musician Richard Lewis Spencer, who owned the copyright for the widely sampled Amen break, never received royalties for its use as the statute of limitations for copyright infringement had passed by the time he learnt of the situation.[51] The journalist Simon Reynolds likened it to "the man who goes to the sperm bank and unknowingly sires hundreds of children".[35] Clyde Stubblefield, the performer of the widely sampled drum break from "Funky Drummer", also received no royalties.[52] The owner of sampled material may not always be traceable, and such knowledge is commonly mislaid through corporate mergers, closures and buyouts.[53][54]

DJ Shadow said that artists tended to either see sampling as a mark of respect and a means to introduce their music to new audiences, or to be protective of their legacy and see no benefit.[53] He described the difficulty of arranging compensation for each artist sampled in a work, and gave the example of two artists both demanding more than 50%, a mathematical impossibility. He instead advocated for a process of clearing samples on a musicological basis, by identifying how much of the composition the sample comprises.[55]

According to Fact, early hip-hop sampling was governed by "unspoken" rules forbidding the sampling of recent records, reissues, other hip-hop records or non-vinyl sources, among other restrictions. These rules were relaxed as younger producers took over and sampling became ubiquitous.[34] In 2017, DJ Shadow said that he felt that "music has never been worth less as a commodity, and yet sampling has never been more risky".[55]

Sampling can help popularize the sampled work. For example, the Desiigner track "Panda" (2015) reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100 after Kanye West sampled it on "Father Stretch My Hands, Pt. 2" (2016).[14] Some record labels and other music licensing companies have simplified their clearance processes by "pre-clearing" their records.[56] For example, the Los Angeles record label Now-Again Records has cleared songs produced for West and Pusha T in a matter of hours.[57][58]

Lawsuits

[edit]In 1989, the Turtles sued De La Soul for using an unlicensed sample on their album 3 Feet High and Rising. The Turtles singer, Mark Volman, told the Los Angeles Times: "Sampling is just a longer term for theft. Anybody who can honestly say sampling is some sort of creativity has never done anything creative." The case was settled out of court and set a legal precedent that had a chilling effect on sampling in hip-hop.[59]

In 1991, the songwriter Gilbert O'Sullivan sued the rapper Biz Markie after Markie sampled O'Sullivan's "Alone Again (Naturally)" on the album I Need a Haircut. In Grand Upright Music, Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records Inc, the court ruled that sampling without permission infringed copyright. Instead of asking for royalties, O'Sullivan forced Markie's label, Warner Bros, to recall the album until the song was removed.[60]

The journalist Dan Charnas criticized the ruling, saying it was difficult to apply conventional copyright laws to sampling and that the American legal system did not have "the cultural capacity to understand this culture and how kids relate to it".[61] In 2005, the writer Nelson George described it as the "most damaging example of anti-hip-hop vindictiveness", which "sent a chill through the industry that is still felt".[60] In the Washington Post, Chris Richards wrote in 2018 that no case had exerted more influence on pop music, likening it to banning a musical instrument. Some have accused the law of restricting creativity, while others argue that it forces producers to innovate.[62]

Since the O'Sullivan lawsuit, samples on commercial recordings have typically been taken either from obscure recordings or cleared, an often expensive option only available to successful acts.[62] According to the Guardian, "Sampling became risky business and a rich man's game, with record labels regularly checking if their musical property had been tea-leafed."[13] For less successful artists, the legal implications of using samples pose obstacles; according to Fact, "For a bedroom producer, clearing a sample can be nearly impossible, both financially and in terms of administration."[14] By comparison, the 1989 Beastie Boys album Paul's Boutique is composed almost entirely of samples, most of which were cleared "easily and affordably"; the clearance process would be much more expensive today.[63] The Washington Post described the modern use of well known samples, such as on records by Kanye West, as an act of conspicuous consumption similar to flaunting cars or jewelry.[62] West has been sued several times over his use of samples.[14]

De minimis use

[edit]In 2000, the jazz flautist James Newton filed a claim against the Beastie Boys' 1992 single "Pass the Mic", which samples his composition "Choir". The judge found that the sample, comprising six seconds and three notes, was de minimis (small enough to be trivial) and did not require clearance. Newton lost appeals in 2003 and 2004.[64][65]

In the 2005 case Bridgeport Music, Inc. v. Dimension Films, the hip-hop group N.W.A. were successfully sued for their use of a two-second sample of a Funkadelic song in the 1990 track "100 Miles and Runnin'". The United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit ruled that all samples, no matter how short, required a license.[14] A judge wrote: "Get a license or do not sample. We do not see this as stifling creativity in any significant way."[65]

As the Bridgeport judgement was decided in an American circuit court, lower courts ruling on similar issues are bound to abide by it.[14] However, in the 2016 case VMG Salsoul v Ciccone, the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled that Madonna did not require a license for a short horn sample in her 1990 song "Vogue". The judge Susan Graber wrote that she did not see why sampling law should be an exception to standard de minimis law.[65]

In 2019, the European Court of Justice ruled that the producers Moses Pelham and Martin Haas had illegally sampled a drum sequence from the 1977 Kraftwerk track "Metal on Metal" for the Sabrina Setlur song "Nur Mir". The court ruled that permission was required for recognizable samples; modified, unrecognizable samples could still be used without authorization.[66]

See also

[edit]External links

[edit]- WhoSampled, a website that catalogs samples

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Howell, Steve (August 2005). "The Lost Art Of Sampling: Part 1". Sound on Sound. Archived from the original on 9 December 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ Reggae Wisdom: Proverbs in Jamaican Music. Univ. Press of Mississippi. 2001. ISBN 9781604736595. Archived from the original on 5 May 2024. Retrieved 11 September 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Bryan J. McCann, The Mark of Criminality: Rhetoric, Race, and Gangsta Rap in the War-On-Crime ERA, pages 41-42 Archived 5 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine, University of Alabama Press

- ^ Beaumont-Thomas, Ben (6 September 2017). "Holger Czukay, bassist with Can, dies aged 79". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 12 August 2023. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e McNamee, David (28 September 2009). "Hey, what's that sound: Sampler". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ Hamer, Mick (26 March 2015). "Interview: Electronic maestros". New Scientist. Reed Business Information. Archived from the original on 8 July 2008. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ a b "A brief history of sampling". MusicRadar. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ McNamee, David (22 June 2009). "Hey, what's that sound: Linn LM-1 Drum Computer and the Oberheim DMX". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Milner, Greg (3 November 2011). Perfecting Sound Forever: The Story of Recorded Music. Granta Publications. ISBN 9781847086051. Archived from the original on 9 December 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ "The 10 most important hardware samplers in history". MusicRadar. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ a b c Aciman, Alexander (16 April 2018). "Meet the unassuming drum machine that changed music forever". Vox. Archived from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ a b Vail, Mark (February 2002). "Korg M1 (Retrozone)". Sound on Sound. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- ^ a b c McNamee, David (16 February 2008). "When did sampling become so non-threatening?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Meiselman, Jessica (25 June 2016). "Sampled or stolen? Untangling the knotty world of hip-hop copyright". Fact. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ a b Cant, Tim (1 July 2022). "10 classic sample libraries that changed music". MusicRadar. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ Music, Future (17 March 2011). "A brief history of GarageBand". MusicRadar. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ Tannenbaum, Rob (22 July 2021). "How Splice Became the Hottest Platform on the Beat Market". Billboard. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ Dandridge-Lemco, Ben (8 May 2020). "Get to know the loopmakers behind rap's biggest songs". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Cush, Andy (15 December 2016). "How Hitmaking Producer Frank Dukes Is Reinventing the Pop Music Machine". Spin. Retrieved 4 June 2024.

- ^ Adams, Kelsey. "Frank Dukes' Kingsway Music Library Could Change Sampling Forever". Complex. Retrieved 4 June 2024.

- ^ Lefrak, Mikaela (24 April 2020). "The Library of Congress wants DJs (and you) to make beats using its audio collections". WAMU. Archived from the original on 4 June 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ a b Jones, Rhian (5 August 2022). "'Common decency': Beyoncé's Renaissance sparks debate about the politics of music sampling". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 August 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ^ Inglis, Sam (September 2003). "Steve Gibson & Dave Walters: Recreating Samples |". Sound on Sound. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ a b "Remixing Culture And Why The Art Of The Mash-Up Matters". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ "Hip-hop's most influential sampler gets a 2017 reboot". Engadget. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ Mayumi Yoshida Barakan & Judith Connor Greer (1996). Tokyo city guide. Tuttle Publishing. p. 144. ISBN 0-8048-1964-5. Archived from the original on 23 March 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ a b Carter, Monica (30 June 2011). "It's Easy When You're Big In Japan: Yellow Magic Orchestra at The Hollywood Bowl". The Vinyl District. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- ^ a b Condry, Ian (2006). Hip-hop Japan: rap and the paths of cultural globalization. Duke University Press. p. 60. ISBN 0-8223-3892-0. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "The Essential... Yellow Magic Orchestra". Fact. 22 January 2015. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ Simpson, Dave (24 March 2006). "Brian Eno and David Byrne, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 August 2007. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ Simpson, Dave (24 March 2006). "Brian Eno and David Byrne, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 12 July 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ Sheppard, David (July 2001). "Cash for Questions". Q.

- ^ Myers, Ben (20 January 2011). "Big Audio Dynamite: more pioneering than the Clash?". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ a b Fintoni, Laurent (2 August 2013). "Don't kick the ethics out of sampling: picking up the bullets from the Weeknd's clash with Portishead". Fact. Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Seven seconds of fire". The Economist. 17 December 2011. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ Taylor, Ken (14 August 2012). "The exclusive interview; 'I feel like I've done a lot for the MPC'". Beatport. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ "First album made completely from samples". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 7 August 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ Sullivan, James (30 March 2012). "DJ Shadow's influence looms large". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ^ "The Dirty Heartbeat of the Golden Age". The Village Voice. 6 November 2007. Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ a b Salmon, Richard (March 2008). "Sample Clearance |". Sound on Sound. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ "Just a sample". The Economist. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ "Spotify playlist: 50 tracks that sample the 'Think' break". Mixmag. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Cheal, David (21 February 2015). "The Life of a Song: 'When the Levee Breaks'". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- ^ Eveleth, Rose (24 February 2014). "The world's most sampled song is 'Change the Beat' by Fab 5 Freddy". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ X, Dharmic (20 February 2014). "James Brown is apparently the most sampled artist of all time". Complex. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ Perrone, Pierre (25 March 2011). "Loleatta Holloway: Much-sampled disco diva who sued Black Box over their worldwide hit 'Ride on Time'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ^ Fink, Robert (2005), "The Story of ORCH5, or, the Classical Ghost in the Hip-Hop Machine", Popular Music, 24 (3): 339–356, doi:10.1017/S0261143005000553, JSTOR 3877522

- ^ Fink (2005, p. 6)

- ^ Siedel, George (2016). The Three Pillar Model For Business Decisions: Strategy, Law, Ethics. Michigan: Van Rye Publishing. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-9970566-1-7.

- ^ Marshall, Elizabeth Dilts (21 June 2025). "Doechii's 'Anxiety' Pays Off for Sampled Artists Gotye, Luis Bonfá". Billboard. 137 (10): 23.

- ^ "Amen Break musician finally gets paid". BBC News. 11 November 2015. Archived from the original on 12 September 2023. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (18 February 2017). "Clyde Stubblefield, James Brown's 'Funky Drummer,' Dead at 73". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 19 May 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ a b "DJ Shadow on sampling as a 'collage of mistakes'". NPR. 17 November 2012. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ Brown, August (6 May 2021). "A homeless LA musician helped create a Daft Punk classic. So why hasn't he seen a dime?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ a b Convery, Stephanie (24 May 2017). "DJ Shadow: 'Music has never been worth less, and yet sampling has never been more risky'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ "Future of sample clearance: As easy as tagging friends on Facebook?". MusicTech. 13 September 2019. Archived from the original on 4 June 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Weingarten, Christopher R. (28 June 2018). "Inside the Labels Where Kanye West Finds Many of His Best Samples". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Needham, Jack (29 November 2019). "How to sample without getting sued". Red Bull. Archived from the original on 4 June 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Runtagh, Jordan (8 June 2016). "Songs on Trial: 12 Landmark Music Copyright Cases". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ a b George, Nelson (26 April 2005). Hip Hop America. Penguin. ISBN 9781101007303. Archived from the original on 23 March 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ Philips, Chuck (1 January 1992). "Songwriter wins large settlement in rap suit". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 29 August 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ^ a b c Richards, Chris. "The court case that changed hip-hop — from Public Enemy to Kanye — forever". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ Tingen, Paul (May 2005). "The Dust Brothers: sampling, remixing & the Boat studio". Sound on Sound. Cambridge, UK: SOS Publications Group. ISSN 1473-5326. Archived from the original on 29 May 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ^ "Beastie Boys Emerge Victorious In Sampling Suit". Billboard. 9 November 2004. Archived from the original on 19 November 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Gardner, Eriq (2 June 2016). "Madonna gets victory over 'Vogue' sample at appeals court". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 17 December 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ "Kraftwerk win 20-year sampling copyright case". BBC News. 30 July 2019. Archived from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Beadle, Jeremy J. Will Pop Eat Itself?: Pop Music in the Soundbite Era (1993)

- Katz, Mark. "Music in 1s and 0s: The Art and Politics of Digital Sampling." In Capturing Sound: How Technology has Changed Music (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 137–57. ISBN 0-520-24380-3

- McKenna, Tyrone B. (2000) "Where Digital Music Technology and Law Collide – Contemporary Issues of Digital Sampling, Appropriation and Copyright Law" Journal of Information, Law & Technology.

- Challis, B (2003) "The Song Remains The Same – A Review of the Legalities of Music Sampling"

- McLeod, Kembrew; DiCola, Peter (2011). Creative License: The Law and Culture of Digital Sampling. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-4875-7.

- Ratcliffe, Robert. (2014) "A Proposed Typology of Sampled Material within Electronic Dance Music." Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 6(1): 97–122.

- Patrin, Nate (2020). Bring That Beat Back: How Sampling Built Hip-Hop. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-1-5179-0628-3.

Sampling (music)

View on GrokipediaHistorical Development

Precursors and Early Techniques

The foundational techniques of music sampling emerged from the experimental practices of musique concrète, pioneered by Pierre Schaeffer in France during the late 1940s. Schaeffer, a composer and engineer at Radiodiffusion Française, rejected traditional instrumentation in favor of manipulating pre-recorded sounds captured from everyday environments, such as urban noises and natural phenomena. His approach treated audio recordings as malleable raw material, edited through physical alterations to magnetic tape, establishing a causal link between source capture and transformative reuse that anticipated modern sampling workflows.[11][12] Key early methods involved analog tape splicing, where segments of recorded sound were physically cut and rejoined to create loops, rhythms, or novel timbres; playback reversal to invert audio sequences; and variable-speed manipulation to alter pitch and duration without pitch-shifting artifacts inherent to later digital processes. Schaeffer's Étude aux chemins de fer (1948), derived from train wheel and whistle recordings, demonstrated these techniques by layering spliced fragments into a cohesive composition, marking the first public broadcast of musique concrète on French radio in 1948. These interventions relied on empirical trial-and-error with available technology, including turntables and early tape recorders, to isolate "sound objects" detached from their origins.[13][14][15] Supporting devices, such as the Phonogène—a multi-track tape playback machine co-developed by Schaeffer and Jacques Poullin around 1950—facilitated real-time looping and speed variation of short audio loops, bridging manual editing with performative control. Similar analog practices spread to other composers, including Pierre Henry, who collaborated with Schaeffer in the Groupe de Recherches Musicales (GRM) founded in 1958, extending tape-based collage to include amplified field recordings and rudimentary effects like echo chambers. These precursors emphasized causal manipulation of acoustic waveforms over synthesis, influencing subsequent electronic music by prioritizing fidelity to captured reality over abstract generation, though limited by analog medium's degradation and labor-intensive editing.[16][17]Emergence in the 1970s and 1980s

In the early 1970s, rudimentary sampling techniques arose within New York City's Bronx hip-hop scene, where disc jockeys manually isolated and looped drum breaks from funk and soul vinyl records using dual turntables and crossfaders. DJ Kool Herc is credited with pioneering this "breakbeat" method during a 1973 back-to-school party, extending short percussive segments—often 10 to 20 seconds long—from tracks like The Incredible Bongo Band's "Apache" to sustain dancing energy without full-song repetition.[18] This analog approach, reliant on physical record manipulation rather than digital capture, formed the foundational practice of reusing pre-recorded audio elements, influencing subsequent DJs such as Grandmaster Flash, who in 1977 developed techniques like cutting and scratching to further manipulate breaks.[4] The formalization of sampling as a digital process emerged in the late 1970s with the advent of purpose-built hardware. The Synclavier, introduced in 1977 by New England Digital Corporation, offered early digital sampling capabilities integrated with synthesis and sequencing, though its high cost limited adoption to professional studios. This was followed by the Fairlight CMI in 1979, the first commercially available polyphonic digital sampler, which allowed users to record, edit, and playback audio samples via a computer interface and light pen, coining the term "sampling" in musical contexts. Priced at approximately $25,000 USD, the Fairlight enabled precise manipulation of sounds, as demonstrated in Peter Gabriel's 1980 track "Intruder," where sampled orchestral hits and vocal snippets created novel textures unattainable through traditional instruments.[3][19] Throughout the 1980s, sampling transitioned from experimental novelty to core production tool, particularly in hip-hop and electronic genres, as more accessible devices proliferated. The E-mu Emulator, released in 1981 for around $10,000, provided 8-bit sampling at 27 kHz with 128 KB memory, facilitating drum and bassline recreations in tracks like Afrika Bambaataa's 1982 "Planet Rock," which incorporated elements from Kraftwerk's "Trans-Europe Express." By mid-decade, hip-hop acts such as Eric B. & Rakim employed samplers to layer obscure breaks and riffs, evident in 1986's "Eric B. Is President," while the 1988 launch of the Akai MPC60 introduced pad-based sequencing and time-stretching precursors, empowering producers like DJ Premier to build beats from chopped samples.[20] These advancements shifted sampling from live performance hacks to studio composition, though legal clearance remained informal until high-profile disputes arose later in the decade.[4]Evolution from Analog to Digital Eras

The evolution of sampling transitioned from labor-intensive analog methods reliant on physical media to precise digital processes enabled by electronic storage and processing. Analog techniques predominated through the mid-20th century, drawing from experimental music practices. In 1948, French composer Pierre Schaeffer pioneered musique concrète, recording environmental and instrumental sounds onto magnetic tape and manipulating them through mechanical editing—cutting, splicing, reversing playback, and varying speeds—to compose abstract pieces, establishing foundational principles of sound recombination independent of traditional notation. These methods, while innovative, suffered from signal degradation over repeated plays and imprecise control limited by manual intervention.[11] Electro-mechanical instruments extended analog sampling into popular music. The Chamberlin, developed by Harry Chamberlin in the late 1940s, used short magnetic tape loops (approximately 8 seconds) of recorded instruments mounted behind keys, replaying them upon depression to simulate orchestral timbres without live performers. This concept was commercialized in the Mellotron, introduced in 1963 by Streetly Electronics in England, which similarly triggered pre-recorded tape segments for keyboardists, influencing rock bands like The Beatles on "Strawberry Fields Forever" (1967) but constrained by tape wear, limited sample length, and fixed pitches.[21][22] In parallel, 1970s hip-hop culture adapted turntables as analog sampling proxies. DJ Kool Herc, at a 1973 Bronx party, isolated and extended funk drum breaks ("Amen Brother" by The Winstons being emblematic) by manually switching between two vinyl copies on turntables, creating seamless loops for dancers; techniques evolved with Grandmaster Flash's 1970s innovations in scratching and crossfading, effectively "sampling" record grooves in real-time without recording devices. These turntable manipulations, reliant on physical records and mixer cues, prioritized rhythmic extension over fine-grained editing but laid causal groundwork for sampling's beat-centric ethos in urban music.[23][24] Digital sampling emerged in the late 1970s, supplanting analog limitations through binary encoding that preserved audio fidelity across manipulations. The Fairlight CMI, launched in 1979 by Australian developers Peter Vogel and Kim Ryrie, represented the first viable polyphonic digital sampler, digitizing sounds at 8-bit/8kHz resolution into 1MB memory for keyboard triggering, looping, and waveform editing via a light pen interface; its adoption by producers like Trevor Horn on Yes's "Owner of a Lonely Heart" (1983) demonstrated digital advantages in clean pitch transposition without tape-speed artifacts.[25] Affordability accelerated the shift: E-mu Systems' Emulator I, released in 1981, offered 8-bit sampling at similar rates with floppy-disk storage for user samples, costing around $10,000 versus the Fairlight's $25,000, enabling broader use in studios for hip-hop and pop—e.g., Quincy Jones on Michael Jackson's Thriller (1982). Digital tools facilitated causal innovations like time-stretching and granular synthesis precursors, reducing wear and allowing infinite non-destructive loops, though early memory constraints (e.g., 128KB polyphony limits) necessitated concise samples. By the late 1980s, devices like the Akai MPC60 (1988) integrated sampling with drum sequencing, standardizing workflows for chopping breaks into individual hits, as pivotal in J Dilla's and Pete Rock's productions, marking digital dominance over analog's tactile but ephemeral methods.[26][15]Technical Aspects

Hardware Samplers and Devices

Hardware samplers are dedicated electronic instruments that capture audio from external sources, store it in digital memory, and enable real-time playback, editing, and sequencing for music production. These devices typically feature analog-to-digital converters for sampling, RAM or disk storage for sample retention, and interfaces for manipulation such as pitch shifting, time-stretching, and looping. Early models operated at limited sampling rates and memory capacities, constrained by 1980s computing hardware, but advanced to support multitimbral playback and higher fidelity over time.[27][28] The Fairlight CMI, launched in 1979 by Australian developers Fairlight Instruments, marked the debut of a commercial polyphonic digital sampler-synthesizer. It utilized 16-bit resolution with sampling rates up to 100 kHz mono or 50 kHz stereo, supported by 28 MB of expandable memory allowing several minutes of audio at standard rates. Operators interacted via a video display, lightpen for waveform drawing, and included presets of orchestral samples, enabling artists like Peter Gabriel to integrate sampled sounds into compositions. Its high cost, exceeding $20,000 USD, limited adoption to professional studios despite pioneering additive synthesis alongside sampling.[29][30]

The E-mu Emulator series, introduced in 1981, broadened accessibility with a keyboard-integrated design and floppy disk storage for samples, reducing reliance on costly RAM. The original Emulator offered 8-voice polyphony and 12-bit/27 kHz sampling, evolving to the Emulator II in 1984 with 16-bit/40 kHz capability and multitimbral layering, which gained acclaim for its velocity-sensitive keyboard and effects processing. Priced around $10,000 USD initially, it influenced sound design in genres requiring realistic instrument emulation, though disk access times introduced latency issues.[26][19] Akai's MPC60, released in 1988 and designed by Roger Linn, integrated a 12-bit/40 kHz sampler with a 16-track MIDI sequencer and velocity-sensitive pads, facilitating drum programming and sample chopping central to hip-hop workflows. It provided 1.44 MB floppy storage expandable via SCSI, with 8-voice polyphony, and its swing quantization algorithm preserved groove feel during timing corrections. Subsequent models like the MPC3000 in 1992 upgraded to 16-bit/44.1 kHz sampling and 32 voices, while later iterations such as the MPC2000 (1997) added color screens and effects, sustaining hardware relevance into the 2000s before software dominance. Costs dropped from $5,000 USD for the MPC60 to under $2,000 for mid-1990s units, democratizing production.[31][32] Other notable devices included the Synclavier (1977 onward), emphasizing high-end synthesis integration, and Roland's S-series samplers from 1987, which offered rackmount affordability for live performance. By the late 1990s, hardware samplers faced competition from computer-based alternatives offering unlimited storage and faster editing, though dedicated units persisted for tactile, latency-free operation in live and studio settings.[33][34]

Software Tools and Digital Workflows

Software samplers and digital audio workstations (DAWs) enable sampling workflows that leverage computational processing for audio import, editing, and playback, surpassing hardware limitations in memory and cost. These tools support operations such as loading audio files, mapping samples across keyboard ranges for pitched playback, and applying modulation via envelopes, LFOs, and filters. Unlike early hardware samplers constrained by fixed RAM, software variants utilize host computer storage for extensive libraries, facilitating multisampling where different notes trigger velocity-layered recordings of acoustic instruments.[35] Ableton Live stands out for sample-centric production with its Simpler instrument, which offers modes for classic playback, one-shot triggering, and slice-to-MIDI conversion based on transients, allowing seamless integration into clip-based arrangements. Its warp engine employs algorithms like complex pro mode to decouple tempo from pitch, preserving audio quality during stretching—a feature refined since Live's initial 2001 release. Sampler, an advanced counterpart, extends this with multisample support and granular synthesis for textural manipulation, making it suitable for both beatmaking and experimental sound design.[36][37][38] Other prominent DAWs include Logic Pro, whose Sampler tool—evolving from EXS24—permits zone-based editing and quick sampler conversion from audio regions for rapid instrument creation. FL Studio's Edison editor and Fruity Slicer provide waveform slicing and loop detection, optimized for pattern-based hip-hop and electronic workflows. Dedicated plugins like Native Instruments Kontakt function as hosts for third-party libraries, incorporating KSP scripting for custom behaviors such as round-robin cycling to mimic instrument nuances; Kontakt 8, released September 23, 2024, introduced enhanced modulation and AI-assisted editing.[38][39] Digital workflows commence with audio acquisition—via recording, vinyl digitization, or sample packs—followed by preprocessing in tools like iZotope RX for cleanup, then import for manipulation. Techniques include time-stretching via phase vocoder or granular methods to fit project tempos, pitch-shifting without artifacts, and layering with synthesis for hybrid sounds. Automation and MIDI mapping enable dynamic control, while non-destructive editing preserves originals for iteration. This ecosystem lowers barriers to entry, as mid-range computers handle polyphony exceeding 128 voices, contrasting 1980s hardware's 8-16 polyphony limits, though it demands robust CPUs for low-latency performance.[35][28][40]Sample Manipulation Methods

Sample manipulation in music production encompasses techniques applied to audio excerpts after initial capture to alter their sonic characteristics, integrate them into new compositions, or evade direct recognizability. These methods transform raw samples through digital signal processing, enabling producers to create novel textures and rhythms while often addressing tempo mismatches or harmonic incompatibilities. Common approaches include chopping, pitch shifting, time stretching, reversing, and applying effects, each rooted in hardware like the Akai MPC series or software plugins.[41] Chopping, also known as slicing, divides a sample into discrete segments based on transients or musical phrases, allowing rearrangement into new sequences. This technique, prevalent in hip-hop, facilitates beat creation by reordering drum hits or melodic fragments; for instance, producers slice vinyl breaks to construct loops that align with desired BPMs. Splicing extends this by crossfading segments for seamless transitions, minimizing artifacts from abrupt cuts.[7][42] Pitch shifting adjusts the fundamental frequency of a sample, typically in semitone increments, to match the key of the host track. Early hardware samplers like the Fairlight CMI shifted pitch by varying playback speed, inadvertently altering duration; modern algorithms decouple pitch from time via phase vocoding or granular synthesis, preserving length while transposing. This method enables harmonic integration but can introduce artifacts like formant distortion if not formant-corrected.[43][44] Time stretching extends or compresses sample duration without altering pitch, crucial for syncing audio from diverse sources to a project's tempo. Algorithms such as waveform similarity overlap-add (WSOLA) analyze and resynthesize overlapping grains, reducing metallic artifacts common in older implementations. In electronic music, this allows stretching vocal phrases or loops to fit grid-based arrangements, though excessive manipulation may degrade audio quality.[45][46] Reversing plays samples backward, creating retrograde motifs that add disorientation or texture; producers often layer reversed elements subtly for ambiance. Filtering via EQ sculpts frequency content, emphasizing basslines or attenuating highs to mask origins, while effects like delay and reverb simulate spatial environments. Layering combines manipulated samples for density, and resampling captures processed outputs as new inputs for iterative refinement. These techniques, combinable in DAWs, underscore sampling's creative core, transforming source material into unrecognizable elements.[47][6]Interpolation as an Alternative

Interpolation involves re-recording or re-performing melodic, lyrical, or harmonic elements from a pre-existing musical composition, rather than directly incorporating audio from the original sound recording.[48] This technique, often termed a "replayed sample," allows artists to evoke the essence of source material through new instrumentation or vocals, preserving creative flexibility while sidestepping the need to license the master recording.[49] Unlike sampling, which extracts unaltered audio segments and requires permissions for both the underlying composition and the specific recording, interpolation typically demands only clearance for the composition's copyright, reducing administrative hurdles and costs associated with master use licenses.[50] The practice gained prominence as an alternative following stricter enforcement of sampling regulations in the 1990s, exemplified by the 1991 Grand Upright Music, Ltd. v. Jonathan Williams court ruling, which held that unauthorized sampling constituted copyright infringement and prompted record labels to demand clearances for even brief excerpts.[51] By re-performing elements—such as hiring session musicians to replicate a riff or altering lyrics slightly—producers avoid reproducing the sonic artifacts of the original, like vinyl crackle or specific production choices, though this can dilute the tactile authenticity of direct samples.[52] Legally, interpolation still risks infringement if the re-creation substantially copies protected aspects of the composition, necessitating publisher approval and royalty shares, but it circumvents disputes over "de minimis" use of recordings that courts have increasingly rejected.[53] In hip-hop, interpolation emerged as a workaround amid rising clearance fees, with producers like Dr. Dre frequently employing it to homage funk and soul tracks without archival audio.[54] Its adoption surged in pop music during the 2010s, driven by a litigious industry favoring nostalgia; for instance, a 2023 analysis noted interpolations in hits like Ariana Grande's 2019 "7 Rings," which re-performed elements from Rodgers and Hammerstein's "My Favorite Things" (1959), yielding royalties to the original composers while evading master issues.[55] This method facilitates cross-generational references but has drawn critique for prioritizing commercial viability over innovation, as re-performances often prioritize recognizability over transformative depth.[56] Despite these efficiencies, interpolation does not eliminate all liabilities, as evidenced by ongoing lawsuits alleging uncredited melodic borrowings, underscoring the need for thorough legal vetting.Cultural and Genre-Specific Impact

Foundational Role in Hip-Hop

Sampling emerged as a core technique in hip-hop through the evolution of DJ practices in the late 1970s Bronx party scene, where pioneers like Kool Herc developed the "Merry-Go-Round" method of looping drum breaks from funk and soul records on turntables to extend danceable sections.[18] This manual looping laid the groundwork for later digital replication, emphasizing short, percussive elements that drove rhythmic energy.[3] A pivotal advancement occurred in 1982 with Afrika Bambaataa and the Soulsonic Force's "Planet Rock," produced by Arthur Baker, which incorporated direct samples from Kraftwerk's 1977 track "Trans-Europe Express" alongside Roland TR-808 drum patterns, marking one of the earliest prominent uses of sampling to fuse hip-hop with electronic elements.[57] [58] This track demonstrated sampling's potential to borrow melodic and rhythmic motifs from diverse genres, creating hybrid sounds that expanded hip-hop's sonic palette beyond live instrumentation.[59] Producer Marley Marl further innovated sampling around 1985 during a session at New York's Unique Recording Studio, where he accidentally captured a snare drum sound from a vinyl record into an E-mu drum machine, revealing the feasibility of isolating and reusing specific audio fragments.[60] [61] This "discovery" enabled producers to chop and sequence samples programmatically, shifting from analog manipulation to precise digital construction of beats, as applied in Marl's work with the Juice Crew on tracks like MC Shan's "Down by Law" (1987).[60] By the late 1980s, hardware samplers such as the E-mu SP-1200, released in 1987, became instrumental in hip-hop production, offering 10 seconds of 12-bit sampling time and integrated sequencing that allowed for gritty, compressed drum sounds integral to the genre's "boom bap" aesthetic.[62] [63] Devices like the Akai MPC60, introduced in 1988, built on this by combining sampling with pad-based sequencing, empowering producers to layer obscure record snippets into dense, original compositions that defined hip-hop's golden age.[64] These tools democratized beat-making for independent artists, fostering a culture of crate-digging for rare vinyl sources and establishing sampling as hip-hop's primary method for sonic innovation and cultural interpolation.[62]Applications in Electronic and Pop Music

Sampling emerged as a core technique in electronic music during the 1980s, facilitated by hardware like the Fairlight CMI, which enabled producers to capture and manipulate real-world sounds into rhythmic and melodic elements.[65] This device, priced at around $25,000 upon its 1979 release, was used by artists such as Art of Noise for tracks like "Beat Box" (1983), where sampled percussion and abstract noises formed the foundation of experimental electronic compositions.[65] In genres like house and techno, sampling disco vocals and funk breaks—such as in early Chicago house tracks by producers like Frankie Knuckles—created infectious grooves by looping short phrases, accelerating the genre's spread through clubs by the mid-1980s.[4] In intelligent dance music (IDM) and ambient electronica of the 1990s, artists like Aphex Twin employed granular synthesis and heavy sample manipulation to deconstruct sources into ethereal textures, as heard in albums such as Selected Ambient Works 85-92 (1992), where vinyl crackle and orchestral snippets were pitch-shifted and layered.[66] Trip-hop pioneers Massive Attack integrated soul and jazz samples with electronic beats in Mezzanine (1998), using slowed-down loops to evoke moody atmospheres, influencing subsequent downtempo and chillout subgenres.[3] Modern electronic acts, including Flume, continue this tradition by chopping vocal acapellas and field recordings in software environments, blending them with synthesis for tracks like "Never Be Like You" (2016).[67] Pop music adopted sampling in the 1980s to infuse hits with nostalgic or authoritative hooks, often via expensive samplers like the E-mu Emulator, which processed orchestral hits into synth-like pads for acts such as Duran Duran.[68] By the 1990s, accessible tools like the Akai MPC series democratized the process, enabling producers to craft chart-toppers; for instance, Puff Daddy's "I'll Be Missing You" (1997) sampled The Police's "Every Breath You Take" (1983), topping the Billboard Hot 100 for 11 weeks through its seamless integration of strings and vocals.[69] In the 2000s, Madonna's "Hung Up" (2005) looped ABBA's "Gimme! Gimme! Gimme!" (1979) to drive its disco revival, reaching number one in 45 countries and exemplifying how sampling familiar melodies boosts commercial appeal.[70] This era saw sampling evolve into interpolation hybrids, as in Robin Thicke's "Blurred Lines" (2013), which recreated Marvin Gaye's "Got to Give It Up" (1977) rhythms without direct lifts, yet still sparking legal scrutiny.[71] The Akai MPC, debuting with the MPC60 in 1988, bridged electronic and pop workflows by combining sampling with sequencing, used by pop-leaning electronic producers for precise drum programming and melody flips.[72] Its pad-based interface facilitated rapid iteration, contributing to the polished sound of 1990s pop-rap crossovers and persisting in contemporary pop production via emulations.[65] Overall, sampling in these genres prioritizes transformative reuse, where source material is often obscured through effects, underscoring its role in innovation over mere replication.[66]Cross-Genre Influences and Notable Samples

Sampling techniques originating in hip-hop production during the 1970s and 1980s facilitated the extraction and reconfiguration of musical elements from disparate genres, enabling producers to blend jazz, funk, soul, and rock into rhythmic foundations that transcended stylistic boundaries. This cross-pollination is evident in the frequent use of jazz recordings from labels like Blue Note, where tracks by artists such as Grant Green and Ronnie Foster provided harmonic and percussive loops for hip-hop compositions, as in A Tribe Called Quest's "Electric Relaxation" (1993) drawing from Ronnie Foster's "Mystic Brew" (1972).[73] Similarly, funk breaks like Lyn Collins' "Think (About It)" (1972), produced by James Brown, were looped into hip-hop staples, influencing subsequent electronic subgenres by providing versatile drum patterns adaptable to faster tempos in drum and bass.[74] The Amen break from The Winstons' "Amen, Brother" (1969), a soul-jazz instrumental, exemplifies prolific cross-genre utility, sampled over 6,800 times across hip-hop (e.g., N.W.A.'s "Straight Outta Compton," 1988), electronic (e.g., in jungle tracks by Goldie), and even pop contexts, due to its concise, high-energy snare and hi-hat configuration that supported tempo manipulation without pitch distortion in early digital samplers.[75] This diffusion extended sampling's reach into rock and electronic music; for instance, hip-hop's interpolation of Kraftwerk's synthesizer melodies from "Numbers" (1981) in Afrika Bambaataa's "Planet Rock" (1982) bridged electro-funk with German experimental electronic, inspiring later house and techno producers to sample industrial and synth-pop sources.[8][76] Notable samples highlight genre fusion's creative and commercial impact:| Original Track | Artist/Genre (Year) | Sampled In | Artist/Genre (Year) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "Rise" | Herb Alpert/jazz-funk (1979) | "Buffalo Gals" | Malcolm McLaren/hip-hop (1982); later "Top Billin'" by Audio Two/hip-hop (1987) | Trumpet riff repurposed as a foundational hip-hop loop, influencing pop and electronic adaptations.[74] |

| "Straight to Hell" | The Clash/punk rock (1982) | "Paper Planes" | M.I.A./alternative hip-hop (2007) | Guitar riff and vocal snippet integrated into a global pop hit, exemplifying rock-to-hip-hop transfer.[77] |

| "Trans-Europe Express" | Kraftwerk/electronic (1977) | Multiple, e.g., "Planet Rock" | Afrika Bambaataa/electro-hip-hop (1982) | Robotic vocals and sequencer patterns sampled to pioneer electro, crossing into mainstream pop via later derivatives.[76] |

| "Heather" | Billy Cobham/jazz fusion (1974) | "93 'Til Infinity" | Souls of Mischief/hip-hop (1993) | Drum groove layered with West Coast rap, demonstrating jazz's rhythmic influence on alternative hip-hop.[74] |