Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Turntablism

View on Wikipedia

Turntablism is the art of manipulating sounds and creating new music, sound effects, mixes and other creative sounds and beats, typically by using two or more turntables and a cross fader-equipped DJ mixer.[1] The mixer is plugged into a PA system (for live events) or broadcasting equipment (if the DJ is performing on radio, TV or Internet radio) so that a wider audience can hear the turntablist's music. Turntablists typically manipulate records on a turntable by moving the record with their hand to cue the stylus to exact points on a record, and by touching or moving the platter or record to stop, slow down, speed up or, spin the record backwards, or moving the turntable platter back and forth (the popular rhythmic "scratching" effect which is a key part of hip hop music),[2] all while using a DJ mixer's cross-fader control and the mixer's gain and equalization controls to adjust the sound and level of each turntable. Turntablists typically use two or more turntables and headphones to cue up desired start points on different records (Greasley & Prior, 2013).

Turntablists, often called DJs (or "deejays"), generally prefer direct-drive turntables over belt-driven or other types, because the belt can be stretched or damaged by "scratching" and other turntable manipulation such as slowing down a record, whereas a direct drive turntable can be stopped, slowed down, or spun backwards without damaging the electric motor. The word turntablist is claimed to be originated by Luis "DJ Disk" Quintanilla (Primus, Herbie Hancock, Invisibl Skratch Piklz).[3] After a phone conversation with Disk, it was later popularised in 1995 by DJ Babu[4] to describe the difference between a DJ who simply plays and mixes records and one who performs by physically manipulating the records, stylus, turntables, turntable speed controls and mixer to produce new sounds. The new term coincided with the resurgence of hip-hop DJing in the 1990s.

According to most DJ historians, it has been documented that "DJ Babu" of the "Beat Junkies" / "Dilated Peoples" was the one who originally coined the term "turntablist". In 1995 while working on the groundbreaking mixtape "Comprehension", DJ Babu hand wrote the name "Babu The Turntablist" on hundreds of copies of this mixtape to describe his style of DJing, while working on the track "Turntablism" with "D-Styles" and DJ Melo-D, Babu would say "if someone plays the piano, we call them a pianist, if someone plays the guitar, we call them a guitarist, why don't we call ourselves Turntablists?" found in the documentary "Scratch (2001 film)" which was released in 2001.

John Oswald described the art: "A phonograph in the hands of a 'hiphop/scratch' artist who plays a record like an electronic washboard with a phonographic needle as a plectrum, produces sounds which are unique and not reproduced—the record player becomes a musical instrument."[5] Some turntablists use turntable techniques like beat mixing/matching, scratching, and beat juggling. Some turntablists seek to have themselves recognized as traditional musicians capable of interacting and improvising with other performers. Depending on the records and tracks selected by the DJ and their turntablist style (e.g., hip hop music), a turntablist can create rhythmic accompaniment, percussion breaks, basslines or beat loops, atmospheric "pads", "stabs" of sudden chords or interwoven melodic lines.

The underground movement of turntablism has also emerged to focus on the skills of the DJ. In the 2010s, there are turntablism competitions, where turntablists demonstrate advanced beat juggling and scratching skills.

History

[edit]Precursors

[edit]The use of the turntable as a musical instrument has its roots dating back to the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s when musique concrète composers did experiments with audio equipment. Experimental composers (such as John Cage, Halim El-Dabh, and Pierre Schaeffer) used them to sample and create music that was entirely produced by the turntable. Cage's Imaginary Landscape No. 1 (1939) is composed for two variable speed turntables, frequency recordings, muted piano and cymbal. Edgard Varèse experimented with turntables even earlier in 1930, though he never formally produced any works using them. Though this school of thought and practice is not directly linked to the 1970s–2010 definition of turntablism within hip hop and DJ culture, it has had an influence on modern experimental sonic/artists such as Christian Marclay, Janek Schaefer, Otomo Yoshihide, Philip Jeck, and Maria Chavez. Turntablism as it is known today, however, did not surface until the advent of hip hop in the 1970s.

Examples of turntable effects can also be found on popular records produced in the 1960s and 1970s. This was most prominent in Jamaican dub music of the 1960s,[6] among deejays in the Jamaican sound system culture. Dub music introduced the techniques of mixing and scratching vinyl,[7] which Jamaican immigrants introduced to American hip hop culture in the early 1970s.[8] Beyond dub music, Creedence Clearwater Revival's 1968 self-titled debut album features a backspin effect in the song "Walk on the Water".

Direct-drive turntables

[edit]Turntablism has origins in the invention of direct-drive turntables. Early belt-drive turntables were unsuitable for turntablism, since they had a slow start-up time, and they were prone to wear-and-tear and breakage,[9] as the belt would break from backspinning or scratching.[10] The first direct-drive turntable was invented by Shuichi Obata, an engineer at Matsushita (now Panasonic),[11] based in Osaka, Japan.[9] It eliminated belts, and instead employed a motor to directly drive a platter on which a vinyl record rests.[12] In 1969, Matsushita released it as the SP-10,[12] the first direct-drive turntable on the market,[13] and the first in their influential Technics series of turntables.[12] In 1971, Matsushita released the Technics SL-1100. Due to its strong motor, durability, and fidelity, it was adopted by early hip hop artists.[12]

A forefather of turntablism was DJ Kool Herc, an immigrant from Jamaica to New York City.[13] He introduced turntable techniques from Jamaican dub music,[8] while developing new techniques made possible by the direct-drive turntable technology of the Technics SL-1100, which he used for the first sound system he set up after emigrating to New York.[13] The signature technique he developed was playing two copies of the same record on two turntables in alternation to extend the b-dancers' favorite section,[8] switching back and forth between the two to loop the breaks to a rhythmic beat.[13]

The most influential turntable was the Technics SL-1200,[14] which was developed in 1971 by a team led by Shuichi Obata at Matsushita, which then released it onto the market in 1972.[9] It was adopted by New York City hip hop DJs such as Grand Wizard Theodore and Afrika Bambaataa in the 1970s. As they experimented with the SL-1200 decks, they developed scratching techniques when they found that the motor would continue to spin at the correct RPM even if the DJ wiggled the record back and forth on the platter.[14] Since then, turntablism spread widely in hip hop culture, and the SL-1200 remained the most widely used turntable in DJ culture for the next several decades.[12][14]

Hip-hop

[edit]

Turntablism as a modern art form and musical practice has its roots within African-American inner city hip-hop of the late 1970s. Kool Herc (a Jamaican DJ who immigrated to New York City), Afrika Bambaataa and Grandmaster Flash are widely credited for having cemented the now established role of DJ as hip hop's foremost instrumentalist.[15] Kool Herc's invention of break-beat DJing is generally regarded as the foundational development in hip hop history, as it gave rise to all other elements of the genre. His influence on the concept of "DJ as turntablist" is equally profound.

To understand the significance of this achievement, it is important to first define the "break". Briefly, the "break" of a song is a musical fragment only seconds in length, which typically takes the form of an "interlude" in which all or most of the music stops except for the percussion. Kool Herc introduced the break-beat technique as a way of extending the break indefinitely. This is done by buying two of the same record, finding the break on each record, and switching from one to the other using the DJ mixer: e.g., as record A plays, the DJ quickly backtracks to the same break on record B, which will again take the place of A at a specific moment where the audience will not notice that the DJ has switched records. Using that idea, Grandmaster Flash elaborated on Kool Herc's invention of break-beat DJing and came up with the quick-mix theory, in which Flash sectioned off a part of the record like a clock.[16] He described it as being "...like cutting, the backspin, and the double-back."[16]

Kool Herc's revolutionary techniques set the course for the development of turntablism as an art form in significant ways. Most important, however, he developed a new form of DJing that did not consist of just playing and mixing records one after the other. The type of DJ that specializes in mixing a set is well respected for his/her own set of unique skills, but playlist mixing is still DJing in the traditional sense. Kool Herc instead originated the idea of creating a sequence for his own purposes, introducing the idea of the DJ as the "feature" of parties, whose performance on any given night would be different from on another night, because the music would be created by the DJ, mixing a bassline from one song with a beat from another song (Greasley & Prior, 2013). The DJ would be examined critically by the crowd on both a technical and entertainment level.

Grand Wizzard Theodore, an apprentice of Flash, who accidentally isolated the most recognizable technique of turntablism: scratching. He put his hand on a record one day, to silence the music on the turntable while his mother was calling out to him and thus accidentally discovered the sound of scratching by moving the record back and forth under the stylus. Though Theodore discovered scratching, it was Flash who helped push the early concept and showcase it to the public, in his live shows and on recordings. DJ Grand Mixer DXT is also credited with furthering the concept of scratching by practicing the rhythmic scratching of a record on one or more turntables (often two), using different velocities to alter the pitch of the note or sound on the recording (Alberts 2002). DXT appeared (as DST) on Herbie Hancock's hit song "Rockit".[15] These early pioneers cemented the fundamental practice that would later become the emerging turntablist art form. Scratching would during the 1980s become a staple of hip hop music, being used by producers and DJs on records and in live shows. By the end of the 1980s it was very common to hear scratching on a record, generally as part of the chorus of a track or within its production.

On stage the DJ would provide the music for the MCs to rhyme and rap to, scratching records during the performance and showcasing his or her skills alongside the verbal skills of the MC. The most well known example of this 'equation' of MCs and DJ is probably Run-D.M.C. who were composed of two MCs and one DJ. The DJ, Jam Master Jay, was an integral part of the group since his turntablism was critical to Run DMC's productions and performances. While Flash and Bambaataa were using the turntable to explore repetition, alter rhythm and create the instrumental stabs and punch phrasing that would come to characterize the sound of hip hop, Grandmaster DST was busy cutting "real" musicians on their own turf. His scratching on Herbie Hancock's 1983 single, "Rockit", makes it perhaps the most influential DJ track of them all – even more than (Grandmaster Flash's) "Wheels of Steel", it established the DJ as the star of the record, even if he wasn't the frontman. Compared to "Rockit", West Street Mob's "Break Dancin' – Electric Boogie" (1983) was punk negation. As great as "Break Dancin'" was, though, it highlighted the limited tonal range of scratching, which was in danger of becoming a short-lived fad like human beat-boxing until the emergence of Code Money's DJ Brethren from Philadelphia in the mid-1980s.

Despite New York's continued pre-eminence in the hip-hop world, scratch DJing was modernized less than 100 miles down the road in Philadelphia, where the climate for the return of the DJ was created by inventing transformer scratching. Developed by DJ Spinbad, DJ Cash Money and DJ Jazzy Jeff, transforming was basically clicking the fader on and off while moving a block of sound (a riff or a short verbal phrase) across the stylus. Expanding the tonal as well as rhythmic possibilities of scratching, the transformer scratch epitomized the chopped-up aesthetic of hip hop culture. Hip hop was starting to become big money and the cult of personality started to take over. Hip hop became very much at the service of the rapper and Cash Money and DJ Jazzy Jeff were accorded maybe one track on an album – for example, DJ Jazzy Jeff's "A Touch of Jazz" (1987) and "Jazzy's in the House" (1988) and Cash Money's "The Music Maker" (1988). Other crucial DJ tracks from this period include Tuff Crew's DJ Too Tuff's "Behold the Detonator" "Soul Food" (both 1989)", and Gang Starr's "DJ Premier in Deep Concentration" (1989).

Decline in role of DJ in hip hop

[edit]The appearance of turntablists and the birth of turntablism was prompted by one major factor – the disappearance or downplaying of the role of the DJ in hip-hop groups, on records and in live shows at the turn of the 1990s. This disappearance has been widely documented in books and documentaries (among them Black Noise and Scratch), and was linked to the increased use of DAT tapes and other studio techniques that would ultimately push the DJ further away from the original hip-hop equation of the MC as the vocalist and the DJ as the music provider alongside the producer. This push and disappearance of the DJ meant that the practices of the DJ, such as scratching, went back underground and were cultivated and built upon by a generation of people who grew up with hip hop, DJs and scratching. By the mid-90s the disappearance of the DJ in hip hop had created a sub-culture which would come to be known as turntablism and which focused entirely on the DJ using his turntables and a mixer to manipulate sounds and create music. By pushing the practice of DJing away, hip hop created the grounds for this sub-culture to evolve (Greasley & Prior, 2013).

Coining of terms

[edit]The origin of the terms turntablist and turntablism are widely contested and argued about, but over the years some facts have been established by various documentaries (Battlesounds, Doug Pray's Scratch), books (DJ Culture), conferences (Skratchcon 2000) and interviews in online and printed magazines. These facts are that the origins of the words most likely lay with practitioners on the US West Coast, centered on the San Francisco Bay Area. Some claim that DJ Disk, a member of the Invisibl Skratch Piklz, was the first to coin the term, others claim that "DJ Babu", a member of the "Beat Junkies", was responsible for coining and spreading the term turntablist after inscribing it on his mixtapes as"Babu the Turntablist" and passing them around. Another claim credits DJ Supreme, 1991 World Supremacy Champion and DJ for Lauryn Hill. The truth most likely lies somewhere in between all these facts.

In an interview with the Spin Science online resource in 2005, "DJ Babu" added the following comments about the birth and spread of the term:

It was around 95, I was heavily into the whole battling thing, working on the tables constantly, mastering new techniques and scratches...[I] made this mixtape called "Comprehension", and on there was a track called "Turntablism" which featured Melo-D and D-Styles. And this is part of where this whole thing about turntablist came from. This was a time where [sic] all these new techniques were coming out, like flares and stuff, and there were probably 20 people or so, in around California between Frisco and LA, who knew about these. So we worked on them, talked about it and kicked about the ideas that these techniques and new ways of scratching gave us.[citation needed]

Mid- to late 1990s

[edit]By the mid- to late 1990s the terms "turntablism" and "turntablist" had become established and accepted to define the practice and practitioner of using turntables and a mixer to create or manipulate sounds and music. This could be done by scratching a record or manipulating the rhythms on the record either by drumming, looping or beat juggling. The decade of the 1990s is also important in shaping the turntablist art form and culture as it saw the emergence of pioneering artists (Mix Master Mike, DJ Qbert, DJ Quest, DJ Krush, A-Trak, Ricci Rucker, Mike Boo, Pumpin' Pete, Prime Cuts) and crews (Invisibl Skratch Piklz, Beat Junkies, The Allies, X-Ecutioners), record labels (Asphodel), DJ Battles (DMC) and the evolution of scratching and other turntablism practices such as Beat Juggling which are viewable in the IDA (International DJ Association/ITF) World Finals.

Techniques

[edit]More sophisticated methods of scratching were developed during that decade, with crews and individual DJs concentrating on the manipulation of the record in time with the manipulation of the cross fader on the mixer to create new rhythms and sonic artifacts with a variety of sounds. The evolution of scratching from a fairly simple sound and simple rhythmic cadences to more complicated sounds and more intricate rhythmical patterns allowed the practitioners to further evolve what could be done with scratching musically. These new ways of scratching were all given names, from flare to crab or orbit, and spread as DJs taught each other, practiced together or just showed off their new techniques to other DJs. Alongside the evolution of scratching, other practices such as drumming (or scratch drumming) and beat juggling were also evolved significantly during the 1990s.

Beat juggling was invented by Steve Dee, a member of the X-Men (later renamed X-Ecutioners) crew. Beat juggling essentially involves the manipulation of two identical or different drum patterns on two different turntables via the mixer to create a new pattern. A simple example would be to use two copies of the same drum pattern to evolve the pattern by doubling the snares, syncopating the drum kick, adding rhythm and variation to the existing pattern. From this concept, which Steve Dee showcased in the early 1990s at DJ battles, Beat Juggling evolved throughout the decade to the point where by the end of it, it had become an intricate technique to create entirely new "beats" and rhythms out of existing, pre-recorded ones (van Veen & Attias, 2012). These were now not just limited to using drum patterns, but could also consist of other sounds – the ultimate aim being to create a new rhythm out of the pre-recorded existing ones. While beat juggling is not as popular as scratching due to the more demanding rhythmical knowledge it requires, it has proved popular within DJ battles and in certain compositional situations (van Veen & Attias, 2012).

Studies

[edit]One of the earliest academic studies of turntablism (White 1996) argued for its designation as a legitimate electronic musical instrument—a manual analog sampler—and described turntable techniques such as backspinning, cutting, scratching and blending as basic tools for most hip hop DJs. White's study suggests the proficient hip-hop DJ must possess similar kinds of skills as those required by trained musicians, not limited to a sense of timing, hand–eye coordination, technical competence and musical creativity. By the year 2000, turntablism and turntablists had become widely publicized and accepted in the mainstream and within hip hop as valid artists. Through this recognition came further evolution.

Evolution

[edit]This evolution took many shapes and forms: some continued to concentrate on the foundations of the art form and its original links to hip hop culture, some became producers utilizing the skills they'd learnt as turntablists and incorporating those into their productions, some concentrated more on the DJing aspect of the art form by combining turntablist skills with the trademark skills of club DJs, while others explored alternative routes in utilizing the turntable as an instrument or production tool solely for the purpose of making music – either by using solely the turntable or by incorporating it into the production process alongside tools such as drum machines, samplers, computer software, and so on. Digital turntablism techniques later was coined into a term called controllerism, which inspired a movement of new digital DJs such as DJ Buddy Holly and Moldover. DJ Buddy and Moldover went on to create a song called "Controllerism" that pays homage to the sound of digitally emulated turntablism.

New DJs, turntablists and crews owe a distinct debt[why?] to pioneer old-school DJs like Kool DJ Herc, Grand Wizard Theodore, Grandmixer DST, Grandmaster Flash, and Afrika Bambaataa, also DJ Jazzy Jeff, DJ Cash Money, DJ Scratch, DJ Clark Kent, and other DJs of the golden age of hip hop, who originally developed many of the concepts and techniques that evolved into modern turntablism. Within the realm of hip hop, notable modern turntablists are the cinematic[when defined as?] DJ Shadow, who influenced Diplo and RJD2, among others,[citation needed] and the experimental DJ Spooky, whose Optometry albums showed that the turntablist can perfectly fit within a jazz setting.[according to whom?] Mix Master Mike was a founding member of the influential turntablist group Invisibl Skratch Piklz (begun in 1989 as Shadow of the Prophet) and later DJ for the Beastie Boys. Cut Chemist, DJ Nu-Mark, and Kid Koala are also known[by whom?] as virtuosi of the turntables.

Concerto for Turntable

[edit]Concerto for Turntable is a groundbreaking musical work that integrates the art of turntablism with classical music composition. Co-created by DJ Radar and Raul Yanez, a composer and professor at Arizona State University, this composition showcases a unique melding of electronic and orchestral music elements. The concerto was first performed in notable venues including Carnegie Hall, symbolizing its acceptance into the classical music tradition.[17] The project was initially supported by Red Bull, which helped to sponsor its development and the premiere performance.[18] The concerto debuted at Arizona State University's Gammage Auditorium before its major premiere at Carnegie Hall on October 2, 2005.[19]

The Concerto for Turntable features a turntable as the solo instrument, complemented by a full symphony orchestra. This arrangement necessitated the development of "scratch notation" by DJ Radar to transcribe his turntable manipulations into a format readable by classically trained musicians. This innovative scoring method was crucial for integrating the turntable's electronic sounds with the acoustic orchestra.[20]

The premiere at Carnegie Hall was met with enthusiastic responses, highlighting the potential of digital instruments within classical music settings and demonstrating the artistic validity of turntablism.[21]

Techniques

[edit]Chopped and screwed

[edit]Starting in the 1980s in the Southern United States and burgeoning in the 2000s, a meta-genre of hip hop called "chopped and screwed" became a significant and popular form of turntablism. Often using a greater variety of vinyl emulation software rather than normal turntables, "chopped and screwed" stood out from previous standards of turntablism in its slowing of the pitch and tempo ("screwing") and syncopated beat skipping ("chopping"), among other added effects of sound manipulation.

DJ Screw Robert Earl Davis of Texas, innovated the art of chopping and screwing coining the phrase "chopped n screwed", taking original contemporary hit records and replaying them in the "chopped n screwed" art form. This gained a very large following finally paving the way for small, independent rap labels to turn a decent profit. However, it is thought by many that DJ Michael Price started slowing down vinyl recordings before the era of DJ Screw.

This form of turntablism, which is usually applied to prior studio recordings (in the form of custom mixtapes) and is not prominent as a feature of live performances, de-emphasizes the role of the rapper, singer or other vocalist by distorting the vocalist's voice along with the rest of the recording (van Veen & Attias, 2012). Arguably, this combination of distortion and audial effects against the original recording grants greater freedom of improvisation to the DJ than did the previous forms of turntablism. Via the ChopNotSlop movement, "Chopped and screwed" has also been applied to other genres of music such as R&B and rock music, thus transcending its roots within the hip-hop genre.[22][23]

Transform

[edit]

A transform is a type of scratch used by turntablists. It is made from a combination of moving the record on the turntable by hand and repeated movement of the crossfader. The name, which has been associated with DJ Cash Money and DJ Jazzy Jeff,[24][25] comes from its similarity to the sound made by the robots in the 1980s cartoon, The Transformers.

Tear

[edit]A tear is a type of scratch used by turntablists. It is made from moving the record on the turntable by hand. The tear is much like a baby scratch in that one does not need the fader to perform it, but unlike a baby scratch, when the DJ pulls the record back he or she pauses his or her hand for a split second in the middle of the stroke. The result is one forward sound and two distinct backward sounds. This scratch can also be performed by doing the opposite and placing the pause on the forward stroke instead. A basic tear is usually performed with the crossfader open the entire time, but it can also be combined with other scratches such as flares for example by doing tears with the record hand and cutting the sound in and out with the fader hand.

Taco Scratch

[edit]

DJ Natural Nate, emerging by the late 1990s as a leading advocate for Breaks music when it was still a niche genre, made significant technical contributions to turntablism. He founded Bruise Your Body Breaks (BYBB), one of the first custom live internet DJ video/radio stations promoting both established and emerging talent globally. Nate's sets are known for their spontaneous transitions and deep rhythmic creativity. Technically, he is widely recognized for inventing both the “Bend” and the “Taco Scratch” techniques, which expanded what DJs could achieve with turntables. These innovations emphasised the idea that the turntable is a true musical instrument, helping shape the sound and performance ethos of Breaks and Electro Breaks. His mentorship and platform-building have also fostered new generations of DJs.

Orbit

[edit]An orbit is a type of scratch used by turntablists. It is generally any scratch that incorporates both a forward and backward movement, or vice versa, of the record in sequence. The orbit was developed by DJ Disk who incorporated the flare after being shown by DJ Qbert.[citation needed] Usually when someone is referring to an orbit, they are most likely talking about flare orbits. For example, A 1 click forward flare and a 1 click backward flare in quick succession (altogether creating 4 very quick distinct sounds) would be a 1 click orbit. A 2 click forward flare and a 2 click backward flare in quick succession (altogether creating 6 very distinct sounds) would be a 2 click orbit, etc. Orbits can be performed once as a single orbit move, or sequenced to produce a cyclical never ending type of orbit sound.

Flare

[edit]

Flare is a type of scratch used by turntablists. It is made from a combination of moving the record on the turntable by hand and quick movement of the crossfader. The flare was invented by its namesake, DJ Flare in 1987. This scratch technique is much like the "transform" in some ways, only instead of starting with the sound that is cutting up off, one starts with the sound on and concentrate on cutting the sound into pieces by bouncing the fader off the cut outside of the fader slot to make the sound cut out and then back in a split second.

Each time the DJ bounces the fader off the side of the fader slot it makes a distinct clicking noise. For this reason, flares are named according to clicks. A simple one click forward flare would be a forward scratch starting with the sound on as the DJ bounces/clicks the fader against the side once extremely quickly in the middle of the forward stroke creating two distinct sounds in one stroke of your record hand and ending with the fader open. In the same manner, 2 clicks, 3 clicks, and even more clicks (if a DJ is fast enough) can be performed to do different types of flares. The discovery and development of the flare scratch was instrumental in elevating this art form to the level of speed and technical scratching that is seen in the 2010s.

Chirp

[edit]

A "chirp" is a type of scratch used by turntablists. It is made with a mix of moving the record and incorporating movement with the crossfade mixer. It was invented by DJ Jazzy Jeff. The scratch is somewhat difficult to perform because it takes a good amount of coordination. The scratch starts out with the cross-fader open. The DJ then moves the record forward while simultaneously closing the previously opened channel ending the first sound. Then, in a reverse fashion, the DJ opens the channel while moving the record backwards creating a more controlled sounding "baby scratch". Done in quick succession it sounds as though a chirp sound is being produced.

Stab

[edit]A "stab" is quite similar to the chirp technique but requires the crossfade mixer to be "closed". The stab requires the user to push the record forward and back quickly and moving the crossfade mixer with a thumb pressed against it, which results in minimal sound coming out, producing a sharp "stabbing" noise".

Crab

[edit]A "crab" is a type of scratch used by turntablists and originally developed by DJ Qbert. It is one of the most difficult scratch techniques to master. The crab is done by pushing the record forward and back while pushing the crossfader mixer open or closed through a quick succession of 4 movements with the fingers. Variations can also include 3 or 2 fingers, and generally it is recommended for beginners to start with 2 fingers and work their way to 4. It is a difficult move to master but also versatile and quite rewarding if done right.

Visual elements

[edit]Visual elements may be linked to turntable movement, incorporating digital media including photographs, graphic stills, film, video, and computer-generated effects into live performance. A separate video mixer is used in combination with the turntable. In 2005 the International Turntablist Federation World final introduced the 'Experimental' category to recognise visual artistry.

Contests

[edit]Like many other musical instrumentalists, turntablists compete to see who can develop the fastest, most innovative and most creative approaches to their instrument. The selection of a champion comes from the culmination of battles between turntablists. Battling involves each turntablist performing a routine (A combination of various technical scratches, beat juggles, and other elements, including body tricks) within a limited time period, after which the routine is judged by a panel of experts. The winner is selected based upon score. These organized competitions evolved from actual old school "battles" where DJs challenged each other at parties, and the "judge" was usually the audience, who would indicate their collective will by cheering louder for the DJ they thought performed better. The DMC World DJ Championships has been hosted since 1985. There are separate competitions for solo DJs and DJ teams, the title of World Champion being bestowed on the winners of each. They also maintain a turntablism hall of fame.[26]

Role of women

[edit]This section contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. (January 2019) |

This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (December 2024) |

In Western popular music, women musicians have achieved great success in singing and songwriting roles, with top examples being Madonna, Celine Dion and Rihanna. However, there are relatively few women DJs or turntablists. Part of this may stem from a general low percentage of women in audio technology-related jobs. In a 2013 Sound on Sound article Rosina Ncube attested that few women work in the record production and sound engineering industry.[27] Ncube claimed that "[n]inety-five percent of music producers are male"[27] and that female producers are less well-known than their male counterparts despite accomplishing great feats within the music industry.[27] The vast majority of students in music technology programs are male.[citation needed]

In hip hop music, the low percentage of women DJs and turntablists may stem from the overall male domination of the entire hip hop music industry. Most of the top rappers, MCs, DJs, record producers and music executives are men. There are a small number of high-profile women, but they are rare. In 2007, University of North Carolina music professor Mark Katz's article stated that it is rare for women to compete in turntable battles and that this gender disparity has become a topic of conversation among the hip-hop DJ community.[28] In 2010, Rebekah Farrugia stated that in the EDM sphere, a male-centric culture has contributed to the marginalisation of women who seek to engage and contribute.[29] Whilst turntablism and broader DJ practices should not be conflated, Katz suggests that the broad use, or lack of use, of the turntable by women across genres and disciplines is impacted by "male technophilia".[28] Historian Ruth Oldenziel concurs in her writing on female engagement with engineering technology.[30] Oldenziel argues that socialization is a central factor in the lack of female engagement with technology, insisting that the historical socialisation of boys as technophiles has contributed to the prevalence of men who engage with technology.[30]

Lucy Green, professor of music at the University College London, focused on gender in relation to musical performers and creators, and specifically on educational frameworks as they relate to both.[31][page needed] She suggests that women's alienation from fields with strong technical aspects such as DJing, sound engineering and music producing should not only be attributed to a feminine dislike towards these instruments.[32] Instead she argues that women entering these fields are forced to complete the difficult task of disrupting a dominant masculine sphere.[32] Despite this,[original research?] women and girls do increasingly engage in turntable and DJ practices, individually[33] and collectively,[34] and "carve out spaces for themselves in EDM and DJ Culture".[29] There are various projects dedicated to the promotion and support of these practices such as Female DJs London.[35] Some artists and collectives go beyond these practices to be more gender inclusive.[36][page needed] For example, Discwoman, a New York-based collective and booking agency, describe themselves as "representing and showcasing cis women, trans women and genderqueer talent."[37]

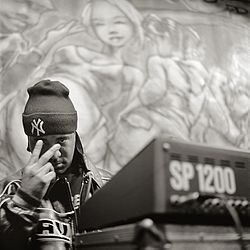

Gallery of turntablists

[edit]-

Afrika Bambaataa (l.)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Art Of Turntablism | History Detectives". PBS. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ globaldjacademy (March 10, 2019). "What is Turntablism? | Turntablism Artists | Turntablist vs DJ | Turntablism Songs". Global Dj Academy. Archived from the original on June 9, 2023. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ Falkenberg Hansen, Kjetil (2010). The acoustics and performance of DJ scratching, analysis and modelling. Stockholm: Skolan för datavetenskap och kommunikation, Kungliga Tekniska högskolan. ISBN 978-91-7415-541-9. OCLC 609824040.

- ^ Newman, Mark "Markski" (January 3, 2003). History of Turntablism. Archived March 20, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Oswald, John (2004). "Bettered by the Borrower: The Ethics of Musical Debt". In Christopher Cox and Daniel Warner (ed.). Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music. The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc. p. 132. ISBN 0-8264-1615-2.

- ^ Collins, Nick; Rincón, Julio d' Escrivan (2007). The Cambridge Companion to Electronic Music. Cambridge University Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-521-86861-7.

- ^ Brown, Andrew (2012). Computers in Music Education: Amplifying Musicality. Routledge. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-135-86598-6.

- ^ a b c Collins, Nick; Schedel, Margaret; Wilson, Scott (2013). Electronic Music. Cambridge University Press. p. 105. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511820540. ISBN 978-1-107-01093-2.

- ^ a b c Coleman, Brian (January 7, 2016). "The Technics 1200 — Hammer Of The Gods [XXL, Fall 1998]". Medium. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ The World of DJs and the Turntable Culture. Hal Leonard Corporation. 2003. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-634-05833-2.

- ^ Steve Trainan (May 21, 1977). "Tracking the next century's disk spinner". Billboard Magazine. Nielsen Business Media. p. 140.

- ^ a b c d e Pinch, Trevor; Bijsterveld, Karin (2012). The Oxford Handbook of Sound Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 515. ISBN 978-0-19-538894-7.

- ^ a b c d Mayhew, Jess (October 2015). "History of the Record Player Part II: The Rise and Fall". Reverb.com. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- ^ a b c Blashill, Pat (May 2002). "Six Machines That Changed The Music World". Wired. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ a b Hansen, Kjetil Falkenberg (2000). Turntable Music Archived June 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Norway: NTNU and Sweden: KTH, p. 4

- ^ a b Chang, Jeff. Can't Stop Won't Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation. Picador, 2005, p 113.

- ^ "Brown cellist joins turntables in Carnegie Hall". October 16, 2005. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ "NYU's Symphony Orchestra to Feature Innovative Music Including "Turntablist" DJ Radar". March 2, 2005. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ "Scratch Fever". September 12, 2002. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ "DJ Radar's Concerto for Turntable". September 30, 2005. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ "Turntable Symphony". October 13, 2005. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ "The Slow Life and Fast Death of DJ Screw". texasmonthly.com. January 20, 2013.

- ^ DJ Screw

- ^ "DJ Cash Money". NAMM.org. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- ^ "Hip Hop Family Tree: DJ Jazzy Jeff / Boing Boing". boingboing.net. April 28, 2015.

- ^ DMC staff. DMC World Champions. Retrieved October 17, 2007

- ^ a b c Ncube, Rosina (September 2013). "Sounding Off: Why So Few Women In Audio?". Sound on Sound.

- ^ a b Katz, Mark (December 12, 2007). "Men, Women, and Turntables: Gender and the DJ Battle". The Musical Quarterly. 89 (4): 580–599. doi:10.1093/musqtl/gdm007.

- ^ a b Farrugia, Rebekah (2013). Beyond the Dance Floor: Female DJs, Technology and Electronic Dance Music Culture. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-1841505664.

- ^ a b Oldenziel, Ruth A. (1997). "Boys and Their Toys: The Fisher Body Craftsman's Guild, 1930–1968, and the Making of a Male Technical Domain". Technology and Culture. 38 (1): 60–96. doi:10.2307/3106784. JSTOR 3106784. S2CID 108698842.

- ^ Green, Lucy (2008). Music, Gender, Education. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521555227.

- ^ a b "Music – GEA – Gender and Education Association". genderandeducation.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved March 12, 2016.

- ^ "Female Turntablists on the Rise". BPMSUPREME TV. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved March 12, 2016.

- ^ "9 All-Female DJ Collectives You Need To Know Right Now". The FADER. February 7, 2016. Retrieved March 12, 2016.

- ^ "Enter". femaledjs.london. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved March 12, 2016.

- ^ Rodgers, Tara (2010). Pink Noises: Women on Electronic Music and Sound. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0822346739.

- ^ "About – Discwoman". discwoman.com. Archived from the original on April 19, 2017. Retrieved March 12, 2016.

- Alberts, Randy. "Scratch and the Hip-Hop Book of Grand Mixer DXT." DigiZine 1/7 (October 2002).

- Shapiro, Peter. Rough Guide to Hip-Hop. Rough Guides, 2001, p. 96.

- White, Miles. "The Phonograph Turntable and Performance Practice in Hip Hop Music." Ethnomusicology OnLine 2 (1996) Retrieved February 4, 2013]

Further reading

[edit]- Eshun, Kodwo. More Brilliant than the Sun. Adventures in Sonic Fiction. London: Quartet Books, 1998. ISBN 0-7043-8025-0

- Katz, Mark. "The Turntable as Weapon: Understanding the DJ Battle." Capturing Sound: How Technology has Changed Music. Rev. ed. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010, pp. 124–45. ISBN 978-0-520-26105-1

- Katz, Mark. Groove Music: The Art and Culture of the Hip Hop DJ. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0-19-533111-0.

- Poschardt, Ulf: DJ Culture. London: Quartet Books, 1998. ISBN 0-7043-8098-6

- Pray, Doug (Dir.). Scratch. 2001. A documentary about the History and Culture of Turntablism.

- Schloss, Joseph G. Making Beats: The Art of Sample-based Hip-hop. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan UP, 2004.

External links

[edit]- What is New York Rap? Australian Broadcasting Corporation. A 1979 radio report on the "new" phenomenon of turntablism.

.jpg/250px-DJ_Q-bert_in_France_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg)