Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Balao-class submarine

View on Wikipedia

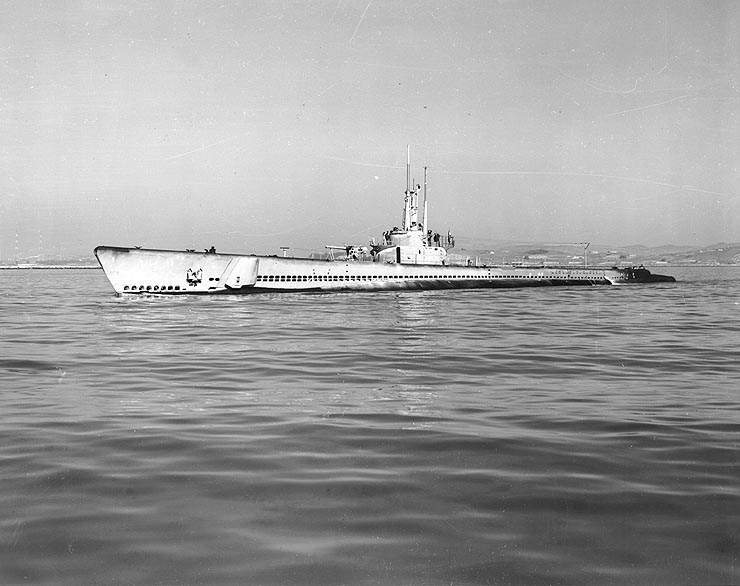

USS Balao in 1944 | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | Balao class |

| Builders | |

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Gato class |

| Succeeded by | Tench class |

| Built | 1942–1946[2] |

| In commission | 1943–present[2] |

| Completed | 120[1] |

| Canceled | 62[1] |

| Active | 1 |

| Lost | 14 (11 in United States service, 3 in foreign service)[1] |

| Retired | 105[1] |

| Preserved | 7[1] |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Diesel-electric submarine |

| Displacement | 1,526 tons (1,550 t) surfaced,[1] 2,391–2,424 tons (2,429–2463 t) submerged[1] |

| Length | 311 ft 6 in–311 ft 10 in (94.9–95.0 m)[1] |

| Beam | 27 ft 3 in–27 ft 4 in (8.3 m)[1] |

| Draft | 16 ft 10 in (5.13 m) maximum[1] |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 20.25 knots (38 km/h) surfaced,[3] 8.75 knots (16 km/h) submerged[3] |

| Range | 11,000 nautical miles (20,000 km) surfaced @ 10 knots (19 km/h)[3] |

| Endurance | 48 hours @ 2 knots (3.7 km/h) submerged,[3] 75 days on patrol |

| Test depth | 400 ft (120 m)[3] |

| Complement | 10 officers, 70–71 enlisted men[3] |

| Armament |

|

The Balao class is a design of United States Navy submarines that was used during World War II, and with 120[1] boats completed, the largest class of submarines in the United States Navy. An improvement on the earlier Gato class, the boats had slight internal differences. The most significant improvement was the use of thicker, higher yield-strength steel in the pressure hull skins and frames,[5] which increased their test depth to 400 feet (120 m). A Balao-class submarine, the USS Tang actually exceeded the maximum on their depth gauge of 612 ft (187 m) in 1944,[6][7] when taking on water in the forward torpedo room while evading a destroyer.[8]

Design

[edit]

The Balaos were similar to the Gatos, except they were modified to increase test depth from 300 ft (90 m) to 400 ft (120 m). In late 1941, two of the Navy's leading submarine designers, Captain Andrew McKee and Commander Armand Morgan, met to explore increasing diving depth in a redesigned Gato. A switch to a new high-tensile steel alloy, combined with an increase in hull thickness from 9⁄16 inch (14.3 mm) to 7⁄8 inch (22.2 mm), would result in a test depth of 450 ft (140 m) and a collapse depth of 900 ft (270 m). However, the limited capacity of the trim pump at deep depths, and lack of time to design a new pump, caused Rear Admiral E. L. Cochrane, chief of the Bureau of Ships, to limit test depth to 400 ft (120 m). Fortunately in 1944, a redesigned Gould centrifugal pump replaced the noisy early-war pump, and effective diving depth was increased.[9]

The Balao boats incorporated the fairwater, conning tower, and periscope shears reduction efforts that were being retrofitted to the Gatos and the preceding classes in the original design, refining the reductions and reducing the sail to the smallest practical size. By the time the boats began to be launched, lessons learned from patrol reports had been worked into the design and the bridge and sail proved to be efficiently laid out, well equipped, and well-liked by the crews.[10]

For the masts and periscope shears, the original arrangement for both the Government and Electric Boat designs had (forward to aft) the two tapered cone-shaped periscope support shears, followed by a thin mast for the SJ surface search radar, and then by a thin mast for the SD air search radar. Minor differences existed in how the periscopes were braced against vibration, but both designs were nearly identical. About halfway through their production run, Electric Boat altered their design, moving the SJ radar mast forward of the periscopes, then altered it again a few boats later by enlarging the SD radar mast. Late in the war, many Balaos built with the original design had the SD air search radar moved slightly aft onto a thickened and taller mast. These mast arrangements, along with the tremendous variation in the gun layout as the war progressed, account for the numerous exterior detail differences among the boats, to the point that at any given time, no two Balaos looked exactly alike.[11]

Engines

[edit]The propulsion of the Balao-class submarines was generally similar to that of the preceding Gato class. Like their predecessors, they were true diesel-electric submarines; their four diesel engines powered electrical generators, and electric motors drove the shafts. No direct connection was made between the main engines and the shafts.

Balao-class submarines received main engines from one of two manufacturers. General Motors Cleveland Model 16-278A V-type diesels or Fairbanks-Morse 38D 8-1/8 nine-cylinder opposed-piston engine. The General Motors Cleveland Model 16-248 V-type as original installations, while boats from Sand Lance onward received 10-cylinder engines. Earlier General Motors boats received Model 16-248 engines, but beginning with Perch Model 16-278A engines were used. In each case, the newer engines had greater displacement than the old, but were rated at the same power; they operated at lower mean effective pressure for greater reliability. [12] Both the Fairbanks-Morse and General Motors engines were two-stroke cycle types.[13]

Unicorn and Vendace were to receive Hooven-Owens-Rentschler diesels, which proved unreliable on previous classes, but both boats were cancelled.

Two manufacturers supplied electric motors for the Balao class. Elliott Company motors were fitted primarily to boats with Fairbanks-Morse engines. General Electric motors were fitted primarily to boats with General Motors engines, but some Fairbanks-Morse boats received General Electric motors. Allis-Chalmers motors were to be used in SS-530 through SS-536, but those seven boats were cancelled before even receiving names.[14]

Most Balao class submarines carried four high-speed electric motors (two per shaft), which had to be fitted with reduction gears to slow their outputs down to an appropriate speed for the shafts. This reduction gearing was very noisy, and made the submarine easier to detect with hydrophones. Nineteen[15][16] [a] late Balao-class submarines were constructed with low-speed double armature motors, which drove the shafts directly and were much quieter, and this improvement was universally fitted on the succeeding Tench class. The new direct-drive electric motors were designed by the Bureau of Ships' electrical division under Captain Hyman G. Rickover, and were first equipped on Sea Owl.[17] Many of the earlier Balao class submarines would be re-fit with the new gearless motor scheme during the GUPPY programs after the war. On all US World War II-built boats, as the diesel engines were not directly connected to the shafts, the electric motors drove the shafts all the time.

Torpedoes

[edit]At the beginning of World War II the standard torpedo for US fleet submarines was the 21-inch, Mark 14 torpedo. Due to a shortage of this torpedo, several substitutions were authorized, including using the shorter Bliss-Leavitt Mark 9 torpedo and Mark 10 torpedo, and the surface-fired Bliss–Leavitt Mark 8 torpedo, Mark 11 torpedo, Mark 12 torpedo, and Mark 15 torpedo. The surface-fired torpedoes required minor modifications. Due to their excessive length, Marks 11, 12, and 15 torpedoes were limited to the aft torpedo tubes only.[18][b]As torpedo production ramped up and the bugs were worked out of the Mark 14, substitutions were less common. As the war progressed, the Navy introduced the electric wakeless Mark 18 Torpedo and the Mark 23 torpedo, a simplified high-speed-only version of the Mark 14. Additionally, a small 19" swim-out acoustic homing Mark 27 torpedo supplemented the armament in fleet boats for defense against escorts. Near the end of the war, the offensive Mark 28 torpedo acoustic homing torpedo was introduced. Well after the war the Mark 37 Torpedo was introduced.[19]

Deck guns

[edit]

Many targets in the Pacific War were sampans or otherwise not worth a torpedo, so the deck gun was an important weapon. Early Balaos began their service with a 4-inch (102 mm)/50 caliber Mk. 9 gun. Due to war experience, most were rearmed with a 5-inch (127 mm)/25 caliber Mk. 17 gun, similar to mounts on battleships and cruisers, but built as a "wet" mount with corrosion-resistant materials, and with power-operated loading and aiming features removed. This conversion started in late 1943, and some boats had two of these weapons beginning in late 1944. Spadefish, commissioned in March 1944, was the first newly built submarine with the purpose-built 5-inch (130 mm)/25 submarine mount. Additional antiaircraft guns included single 40 mm Bofors and twin 20 mm Oerlikon mounts, usually one of each.[20][21]

Mine armament

[edit]Like the previous Tambor/Gar and Gato classes, the Balao class could substitute mines in place of torpedoes. For the Mk 10 and Mk 12 type mines used in World War II, each torpedo could be replaced by as many as two mines, giving the submarine a true maximum capacity of 48 mines. The doctrine, though, was to retain at least four torpedoes on mine-laying missions, which further limits the capacity to 40 mines, and this is often stated as the maximum in various publications. In practice during the war, submarines went out with at least eight torpedoes, and the largest minefields laid were 32 mines. After the war, the Mk 49 mine replaced the Mk 12, while the larger Mk 27 mine was also carried, which only allowed one mine replacing one torpedo. This mine could be set to travel 1000 to 5000 yards from the sub before deploying. (not to be confused with the Mk 27 homing torpedo) [22][23]

Boats in class

[edit]This was the most numerous US submarine class; 120 of these boats were commissioned from February 1943 through September 1948, with 12 commissioned postwar. Nine of the 52 US submarines lost in World War II were of this class, along with five lost postwar, including one in Turkish service in 1953, one in Argentine service in the Falklands War of 1982, and one in Peruvian service in 1988.[1][24] Also, Lancetfish flooded and sank while fitting out at the Boston Naval Shipyard on 15 March 1945. She was raised but not repaired, and was listed with the reserve fleet postwar until struck in 1958. Some of the class served actively in the US Navy through the middle 1970s, and one (Hai Pao ex-Tusk) is still active in Taiwan's Republic of China Navy.

SS-361 through SS-364 were initially ordered as Balao-class, and were assigned hull numbers that fall in the middle of the range of numbers for the Balao class (SS-285 to SS-416 and 425–426).[25] Thus in some references, they are listed with that class.[26] However, they were completed by Manitowoc as Gatos, due to an unavoidable delay in Electric Boat's development of Balao-class drawings. Manitowoc was a follow yard to Electric Boat, and was dependent on them for designs and drawings.[27][1] Also, the Balao class USS Trumpetfish (SS-425) and USS Tusk (SS-426) are listed with the Tench class in some references, as their hull numbers fall in the range of that class.[28][29] These were built by Cramp Shipbuilding, a follow yard for Portsmouth Navy Yard and waited for Government plans.

Cancellations

[edit]In total, 125 U.S. submarines were cancelled during World War II, all but three between 29 July 1944 and 12 August 1945. The exceptions were three Tench-class boats, cancelled 7 January 1946. References vary considerably as to how many of these were Balao and how many were Tench boats. Some references simply assume all submarines numbered after SS-416 were Tench class; however, Trumpetfish (SS-425) and Tusk (SS-426) were completed as Balaos.[30][31] This yields 10 cancelled Balao-class, SS-353-360 and 379–380. The Register of Ships of the U. S. Navy differs, considering every submarine not specifically ordered as a Tench to be a Balao, and further projecting SS-551-562 as a future class.[1] This yields 62 cancelled Balao class, 51 cancelled Tench class, and 12 cancelled future class. Two of the cancelled Balao-class submarines, Turbot (SS-427) and Ulua (SS-428), were launched incomplete and served for years as experimental hulks at Annapolis and Norfolk, Virginia. The cancelled hull numbers, including those launched incomplete, were SS-353–360 (Balao), 379–380 (Balao), 427–434 (Balao), 436–437 (Tench), 438–474 (Balao), 491–521 (Tench), 526–529 (Tench), 530–536 (Balao), 537–550 (Tench), and 551–562 (future).[1]

Service history

[edit]World War II

[edit]

The Balaos began to enter service in mid-1943, as the many problems with the Mark 14 torpedo were being solved. They were instrumental in the Submarine Force's near-destruction of the Japanese merchant fleet and significant attrition of the Imperial Japanese Navy. One of the class, Archerfish, brought down what remains the largest warship sunk by a submarine, the Shinano (59,000 tons). Tang, the highest-scoring of the class, sank 33 ships totaling 116,454 tons, as officially revised upward in 1980.[32]

Nine Balaos were lost in World War II, while two US boats were lost in postwar accidents. In foreign service, one in Turkish service was lost in a collision in 1953, one in Peruvian service was lost in a collision in 1988, and Catfish was sold to the Argentinian Navy. She was renamed the ARA Santa Fe (S-21) and was lost in the 1982 Falklands War after being damaged, when she sank while moored pierside. Santa Fe was refloated and disposed of a few years after the war by being taken out to deep water and scuttled.

Additionally, Lancetfish, commissioned but incomplete and still under construction, flooded and sank pierside at the Boston Navy Yard on 15 March 1945, after a yard worker mistakenly opened the inner door of an aft torpedo tube that already had the outer door open. No personnel were lost in the accident and she was raised, decommissioned, and never completed or repaired.[1][33][34] Her 42 days in commission is the record for the shortest commissioned service of any USN submarine. Postwar, she was laid up in the Reserve Fleet until stricken in 1958 and scrapped in 1959.

Balao class losses

[edit]| Name and hull number | Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| USS Cisco (SS-290) | 28 September 1943 | Lost to air attack and gunboat Karatsu (ex-USS Luzon) |

| USS Capelin (SS-289) | December 1943 | Cause of loss unknown, possibly naval mine or attack by the Wakataka |

| USS Escolar (SS-294) | 17 October - 13 November 1944 | Probably lost to enemy mine |

| USS Shark (SS-314) | 24 October 1944 | Attacked by the Harukaze |

| USS Tang (SS-306) | 25 October 1944 | Sunk by a circular run of own torpedo |

| USS Barbel (SS-316) | 4 February 1945 | Air attack |

| USS Kete (SS-369) | March 1945 | Cause of loss unknown, possibly to mine or enemy action |

| USS Lagarto (SS-371) | 3 May 1945 | Attacked by Hatsutaka |

| USS Bullhead (SS-332) | 6 August 1945 | Sunk by Japanese air attack by a Mitsubishi Ki-51 |

| USS Cochino (SS-345) | 26 August 1949 | Accidental fire |

| TCG Dumlupinar (D-6) (formerly USS Blower (SS-325)) | 4 April 1953 | In Turkish service, lost in collision with MV Naboland |

| USS Stickleback (SS-415) | 28 May 1958 | Collision with USS Silverstein (DE-534) |

| ARA Santa Fe (S-21) (formerly USS Catfish (SS-339)) | 25 April 1982 | In Argentine service, disabled by helicopter attack, sank pierside, and was captured by ground forces during Operation Paraquet - the British recapture of South Georgia during the Falklands War. After the war, she was scuttled in deep water. |

| BAP Pacocha (SS-48) (formerly USS Atule (SS-403)) | 26 August 1988 | In Peruvian service, lost in collision with Japanese fishing trawler Kiowa Maru |

Notable submarines

[edit]- Tang was second on the list of number of ships sunk with 33 and first on the list of tonnage with 116,454. Her third war patrol was the most successful of any U.S. submarine with 10 ships for 39,100 tons. Sunk in the Taiwan Strait by a circular run of her own torpedo, her skipper Richard O'Kane and eight others escaped; some escaped the submerged wreck with the only known successful use of the Momsen Lung. Tang's survivors were imprisoned by the Japanese for the rest of the war. After his release following the Japanese surrender, Richard O'Kane was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions commanding Tang during the convoy battles of 24 and 25 October 1944.

- Archerfish sank the aircraft carrier Shinano. Shinano is the largest ship sunk by a submarine. Commander Enright was awarded the Navy Cross.

- Batfish is preserved as a museum ship in Oklahoma. She is famous for sinking three Japanese submarines, RO-55, RO-112, and RO-113 in a 3 day time span. She is the only US submarine to have sunk 3 ships in a 72 hour period. She also sank the destroyer Samidare.[35]

- Redfish participated in the destruction of two Japanese aircraft carriers. On December 9th, she was part of a submarine wolfpack which damaged the aircraft carrier Junyō beyond repair, then just 10 days later she torpedoed and sank the aircraft carrier Unryū. After the war, Redfish became something of a movie star, playing the role of Jules Verne's Nautilus in the Walt Disney film 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, then played the part of the fictional submarine USS Nerka in the 1958 motion picture Run Silent, Run Deep. She capped her film career by making several appearances in the popular black-and-white television series The Silent Service.

- Sealion launched a torpedo attack which sank the Japanese battleship Kongō and the destroyer Urakaze.[36]

- Blackfin sank the Japanese destroyer Shigure. Up to that point, Shigure was seen as a fortune ship, having survived the entirety of the Solomon Islands campaign without losing a single man in combat, and in turn served in several naval battles, which included helping to sink the submarine USS Growler and being the only Japanese ship of her formation to survive the battles of Vella Gulf and Surigao Strait. Her actions were heavily publicized, and her sinking was a huge blow to Japanese morale.[37]

Postwar service history

[edit]Postwar, 55 Balaos were modernized under the Fleet Snorkel and Greater Underwater Propulsion Power (GUPPY) programs, with some continuing in US service into the early 1970s. The last Balao-class submarine in United States service was USS Clamagore (SS-343), which was decommissioned in June 1975.[38] Seven were converted to roles as diverse as guided-missile submarines (SSG) and amphibious transport submarines (SSP). 46 were transferred to foreign navies for years of additional service, some into the 1990s, and Tusk remains active in Taiwan's Republic of China Navy as Hai Pao.

Naval Reserve trainer

[edit]Interested in maintaining a ready pool of trained reservists, the Navy assigned at least 58 submarines from 1946 to 1971 to various coastal and inland ports (even in Great Lakes ports like Cleveland, Chicago, and Detroit), where they served as training platforms during the Reservists' weekend drills. At least 20 Balao-class boats served in this capacity. In this role, the boats were rendered incapable of diving and had their propellers removed. They were used strictly as pierside trainers. These were in commission but classed as "in service in reserve", thus some were decommissioned and recommissioned on the same day to reflect the change in status.[39][40][41]

Foreign service

[edit]The large numbers of relatively modern, but surplus U.S. fleet submarines proved to be popular in sales, loans, or leases to allied foreign navies. 46 Balao-class submarines were transferred to foreign navies, some shortly after World War II, others after serving nearly 30 years in the US Navy. These included 17 to Turkey, 2 to Greece, 3 to Italy, 2 to the Netherlands, 5 to Spain, 2 to Venezuela, 4 to Argentina, 5 to Brazil, 2 to Chile, 2 to Peru, 1 to Canada and 1 to Taiwan.[41] One of the Venezuelan boats, ARV Carite (S-11) formerly USS Tilefish (SS-307), featured in the 1971 film Murphy's War with some cosmetic modification.

GUPPY and other conversions

[edit]At the end of World War II, the US submarine force found itself in an awkward position. The 111 remaining Balao-class submarines, designed to fight an enemy that no longer existed, were obsolete despite the fact they were only one to three years old. The German Type XXI U-boat, with a large battery capacity, streamlining to maximize underwater speed, and a snorkel, was the submarine of the immediate future. The Greater Underwater Propulsion Power Program (GUPPY) conversion program was developed to give some Balao- and Tench-class submarines similar capabilities to the Type XXI. When the cost of upgrading numerous submarines to GUPPY standard became apparent, the austere "Fleet Snorkel" conversion was developed to add snorkels and partial streamlining to some boats. A total of 36 Balao-class submarines were converted to one of the GUPPY configurations, with 19 additional boats receiving Fleet Snorkel modifications. Two of the GUPPY boats and six of the Fleet Snorkel boats were converted immediately prior to transfer to a foreign navy. Most of the 47 remaining converted submarines were active into the early 1970s, when many were transferred to foreign navies for further service and others were decommissioned and disposed of.[38]

Although there was some variation in the GUPPY conversion programs, generally the original two Sargo batteries were replaced by four more compact Guppy (GUPPY I and II only) or Sargo II batteries via significant re-utilization of below-deck space, usually including removal of auxiliary diesels. All of these battery designs were of the lead-acid type. This increased the total number of battery cells from 252 to 504; the downside was the compact batteries had to be replaced every 18 months instead of every 5 years. The Sargo II battery was developed as a lower-cost alternative to the expensive Guppy battery.[42] All GUPPYs received a snorkel, with a streamlined sail and bow. Also, the electric motors were upgraded to the direct drive double-armature type, along with modernized electrical and air conditioning systems. All except the austere GUPPY IB conversions for foreign transfer received sonar, fire control, and Electronic Support Measures (ESM) upgrades.[43]

The Fleet Snorkel program was much more austere than the GUPPY modernizations, but is included here as it occurred during the GUPPY era. The GUPPY and Fleet Snorkel programs are listed in chronological order: GUPPY I, GUPPY II, GUPPY IA, Fleet Snorkel, GUPPY IIA, GUPPY IB, and GUPPY III.

GUPPY I

[edit]Two Tench-class boats were converted as prototypes for the GUPPY program in 1947. Their configuration lacked a snorkel and was not repeated, so no Balaos received this conversion.

GUPPY II

[edit]

This was the first production GUPPY conversion, with most conversions occurring in 1947–49. Thirteen Balao-class boats (Catfish, Clamagore, Cobbler, Cochino, Corporal, Cubera, Diodon, Dogfish, Greenfish, Halfbeak, Tiru, Trumpetfish, and Tusk) received GUPPY II upgrades. This was the only production conversion with Guppy batteries.

GUPPY IA

[edit]

This was developed as a more cost-effective alternative to GUPPY II. Nine Balao-class boats (Atule, Becuna, Blackfin, Blenny, Caiman, Chivo, Chopper, Sea Poacher, and Sea Robin) were converted in 1951–52. The less expensive Sargo II battery was introduced, along with other cost-saving measures.

Fleet Snorkel

[edit]

The Fleet Snorkel program was developed as an austere, cost-effective alternative to full GUPPY conversions, with significantly less improvement in submerged performance. Twenty-three Balao-class boats (Bergall, Besugo, Brill, Bugara, Carbonero, Carp, Charr, Chub, Cusk, Guitarro, Kraken, Lizardfish, Mapiro, Mero, Piper, Sabalo, Sablefish, Scabbardfish, Sea Cat, Sea Owl, Segundo, Sennet, and Sterlet) received this upgrade, six immediately prior to foreign transfer. Most Fleet Snorkel conversions occurred 1951–52. Unlike the GUPPY conversions, the original pair of Sargo batteries were not upgraded. Each boat received a streamlined sail with a snorkel, along with upgraded sonar, air conditioning, and ESM. The original bow was left in place, except on three boats (Piper, Sea Owl, and Sterlet) that received additional upper bow sonar equipment.[44] A few boats initially retained the 5"/25 deck gun, but this was removed in the early 1950s.

GUPPY IIA

[edit]

This was generally similar to GUPPY IA, except one of the forward diesel engines was removed to relieve machinery overcrowding. Thirteen Balao-class boats (Bang, Diodon, Entemedor, Hardhead, Jallao, Menhaden, Picuda, Pomfret, Razorback, Ronquil, Sea Fox, Stickleback, and Threadfin) received GUPPY IIA upgrades in 1952–54. One of these, Diodon, had previously been upgraded to GUPPY II.

GUPPY IB

[edit]This was developed as an austere upgrade for two Gato-class and two Balao-class boats (Hawkbill and Icefish) prior to transfer to foreign navies in 1953–55. They lacked the sonar and electronics upgrades of other GUPPY conversions.

GUPPY III

[edit]

Nine submarines, six of them Balaos (Clamagore, Cobbler, Corporal, Greenfish, Tiru, and Trumpetfish), were upgraded from GUPPY II to GUPPY III in 1959-63 as part of the Fleet Rehabilitation and Modernization II (FRAM II) program. All except Tiru, the pilot conversion, were lengthened by 15 feet in the forward part of the control room to provide a new sonar space, berthing, electronics space, and storerooms. Tiru was lengthened only 12.5 feet, and both forward diesel engines were removed.[45] The other GUPPY IIIs retained all four engines. A taller "Northern" sail was included, to allow improved surfaced operations in rough seas; this was also backfitted to some other GUPPYs. The BQG-4 Passive Underwater Fire Control Feasibility Study (PUFFS) sonar system, with its three tall domes topside, was fitted. Additionally, fire control upgrades allowed the Mark 45 nuclear torpedo to be used.[46]

Radar picket

[edit]The advent of the kamikaze demonstrated the need for a long range radar umbrella around the fleet. Radar picket destroyers and destroyer escorts were put into service, but they proved vulnerable in this role as they could be attacked as well, leaving the fleet blind. A submarine, though, could dive and escape aerial attack. Four submarines including the Balao-class boat Threadfin prototyped the concept at the end of World War II but were not used in this role.[47] Ten fleet submarines were converted for this role 1946-53 and redesignated SSR as radar picket submarines. Burrfish was the only Balao-class SSR. Experiments on the first two SSR submarines under the appropriately named Project Migraine I showed that placement of the radars on the deck was inadequate and that more room was needed for electronics. Thus Burrfish was given the Migraine II (project SCB 12) conversion, which placed a Combat Information Center (CIC) in the space formerly occupied as the aft battery room. The after torpedo room was stripped and converted into berthing, and the boat lost two of her forward torpedo tubes to make room for additional berthing and electronics. The radars were raised up off the deck and put on masts, giving them a greater range and hopefully greater reliability.[43]

The SSRs proved only moderately successful, as the radars themselves proved troublesome and somewhat unreliable, and the boats' surface speed was insufficient to protect a fast-moving carrier group. The radars were removed and the boats reverted to general purpose submarines after 1959. Burrfish was decommissioned in 1956 and, with her radar equipment removed, transferred to Canada as HMCS Grilse (SS-71) in 1961.[48]

Guided-missile submarine

[edit]

The Regulus nuclear cruise missile program of the 1950s provided the US Navy with its first strategic strike capability. It was preceded by experiments with the JB-2 Loon missile, a close derivative of the German V-1 flying bomb, beginning in the last year of World War II. Submarine testing of Loon was performed 1947–53, with Cusk and Carbonero converted in to guided-missile submarines as test platforms in 1947 and 1948 respectively. Initially the missile was carried on the launch rail unprotected, thus the submarine was unable to submerge until after launch. Cusk was eventually fitted with a watertight hangar for one missile and redesignated as an SSG. Following a brief stint as a cargo submarine, Barbero was converted in 1955 to carry two surface-launched Regulus missiles and was redesignated as an SSG, joining the Gato-class Tunny in this role. She made strategic deterrent patrols with Regulus until 1964, when the program was discontinued in favor of Polaris.[49] A number of fleet boats were equipped with Regulus guidance equipment 1953–64, including Cusk and Carbonero following the Loon tests.

Transport submarine

[edit]

Sealion and Perch were converted to amphibious transport submarines in 1948 and redesignated as SSPs. Initially, they were equipped with a watertight hangar capable of housing a Landing Vehicle Tracked (LVT), and retained one 5-inch (130 mm)/25 caliber deck gun for shore bombardment. Both torpedo rooms and one engine room were gutted to provide space for embarked Special Operations Forces (SOF) and their equipment. Snorkels were fitted. Due to the extra personnel, to avoid excessive snorkeling they were equipped with a CO2 scrubber and extra oxygen storage. Initially, a squadron of 12 SSPs was considered, capable of landing a reinforced Marine battalion, but only two Balao-class SSPs (out of four overall) were actually converted. Perch landed British commandos on one raid in the Korean War, and operated in the Vietnam War from 1965 until assignment to Naval Reserve training in 1967 and decommissioning in 1971, followed by scrapping in 1973. Perch was replaced in the Pacific Fleet transport submarine role by Tunny in 1967 and Grayback in 1968. Sealion operated in the Atlantic, deploying for the Cuban Missile Crisis and numerous SOF-related exercises. She was decommissioned in 1970 and expended as a target in 1978. The LVT hangar and 5-inch (130 mm) gun were removed from both boats by the late 1950s. They went through several changes of designation in their careers: ASSP in 1950, APSS in 1956, and LPSS in 1968.[50][1]

Sonar test submarine

[edit]Baya was redesignated as an auxiliary submarine (AGSS) in 1949 and converted to a sonar test submarine in 1958–59 to test a system known as LORAD. This included a 12-foot (3.7 m) extension aft of the forward torpedo room, with 40-foot (12 m) swing-out arrays near the bow. Later, three large domes were installed topside for a wide aperture array.[51]

Cargo submarine

[edit]Barbero was converted to a cargo submarine and redesignated as an SSA in 1948. The forward engine room, aft torpedo room, and all reload torpedo racks were gutted to provide cargo space. From October 1948 until March 1950, she took part in an experimental program to evaluate her capabilities as a cargo carrier. Experimentation ended in early 1950, and she was decommissioned into the reserve on 30 June 1950. In 1955, she was converted to a Regulus missile submarine and redesignated as an SSG.[52]

Operational submarines

[edit]As of 2007 Tusk, a Balao-class submarine, was one of the last two operational submarines in the world built during World War II. The boat was transferred to Taiwan's Republic of China Navy in the early 1970s. The Tench-class ex-Cutlass is the other one. They are named Hai Pao and Hai Shih, respectively, in Taiwanese service.[53][54]

Museums

[edit]Six Balao-class submarines are open to public viewing. They primarily depend on revenue generated by visitors to keep them operational and up to U.S. Navy standards; each boat gets a yearly inspection and a "report card". Some boats, like Batfish and Pampanito, encourage youth functions and allow a group of volunteers to sleep overnight in the crew's quarters.

Surviving ships

[edit]The following is a complete list of Balao-class museum boats:

- USS Batfish (SS-310) at War Memorial Park in Muskogee, Oklahoma[55]

- USS Becuna (SS-319) at Independence Seaport Museum in Philadelphia[56]

- USS Bowfin (SS-287) at USS Bowfin Submarine Museum & Park in Honolulu[57]

- USS Lionfish (SS-298) at Battleship Cove in Fall River, Massachusetts[58]

- USS Pampanito (SS-383) at San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park in San Francisco[59]

- USS Razorback (SS-394) at Arkansas Inland Maritime Museum in North Little Rock, Arkansas[60]

USS Clamagore (SS-343) served as a museum boat at Patriots Point in Charleston, South Carolina until being closed in 2021 and scrapped two years later. Additionally the USS Ling (SS-297) is aground in the Hackensack River at the site of the former New Jersey Naval Museum. As of 2025, efforts to find a new home for this vessel have been unsuccessful.

Surviving parts

[edit]- USS Ling (SS-297) at New Jersey Naval Museum in Hackensack, New Jersey (Sail)

- USS Baya (SS-318) at Vallejo Naval and Historical Museum in Vallejo, California (Periscope)

- USS Pintado (SS-387) at National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg, Texas (Conning Tower)

- USS Parche (SS-384) at USS Bowfin Submarine Museum & Park in Honolulu (Conning Tower)

- USS Balao (SS-285) at Washington Navy Yard in Washington D.C. (Conning Tower)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The last ten Balao class by Electric Boat (SS-343 - SS-352), the last six by Portsmouth Navy Yard (SS-405 - SS-410), the last one by Mare Island Navy Yard (SS-416), and the last two by Cramp Shipbuilding (SS-425 - SS-426) were all built with low-speed dual-aperture motors that eliminated the need for reduction gears.

- ^ While all of these substitutes are mentioned in the manual, not all were necessarily issued in the war. There is anecdotal evidence for Mark 10 and Mark 15 substitutions having occurred.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Bauer, K. Jack; Roberts, Stephen S. (1991). Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775-1990: Major Combatants. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 275–280. ISBN 0-313-26202-0.

- ^ a b Friedman through 1945, pp. 285–304.

- ^ a b c d e f g Friedman through 1945, pp. 305–311.

- ^ a b U.S. Submarines Through 1945 pp. 305–311

- ^ Peter T. Sasgen (2002). Red Scorpion: The War Patrols of the USS Rasher. Naval Institute Press. p. 17.

- ^ O'Kane 1989, p. 111

- ^ Richard H. O'Kane (1977). Clear the Bridge! The War Patrols of the USS Tang. Presidio Press. p. 40.

- ^ Richard H. O'Kane (1977). Clear the Bridge! The War Patrols of the USS Tang. Presidio Press. p. 111.

- ^ Friedman through 1945, pp. 208-209

- ^ A Visual Guide to the U.S. Fleet Submarines Part Three: Balao and Tench Classes 1942–1950 pp. 2-3, Johnston, David (2012) PigBoats.COM

- ^ Johnston, pp. 3-10

- ^ Alden, John D. (1979). The Fleet Submarine in the U.S. Navy: A Design and Construction History. Naval Institute Press. pp. 90, 210–212. ISBN 0-85368-203-8.

- ^ Stern, Robert C. (2006). "Gato-Class Submarines in action" (PDF) (Press release). Squadron Signal Publications. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ "Submarine Electrical Systems". www.maritime.org/.

- ^ Alden, pp 212 - 213

- ^ Bauer and Roberts, p. 275

- ^ Friedman through 1945, pp. 209-210

- ^ https://maritime.org/doc/fleetsub/tubes/chap11.php#11A8 Ordnance Pamphlet 1085 21-inch Torpedo Tubes Marks 32 to 39 and modifications as in SS-198 and up

- ^ http://navweaps.com/Weapons/WTUS_Main.php NavWeaps.com Weapons-Torpedoes-United States of America

- ^ Johnston, pp. 3-6

- ^ Friedman 1995, pp. 218-219

- ^ ORD696 Operational Characteristics of U.S. Naval Mines

- ^ http://navweaps.com/Weapons/WAMUS_Mines.php NavWeaps.com Weapons-ASW and Mines-United States of America-Mines

- ^ United States Submarine Losses in World War II, Naval History Division, Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, Washington: 1963 (Fifth Printing)

- ^ Fleet Submarine index at NavSource

- ^ Lenton, p. 94

- ^ Friedman through 1945, p. 209

- ^ Lenton, pp. 100-102

- ^ Silverstone, p. 203

- ^ Silverstone, pp. 203-204

- ^ Gardiner and Chesneau, pp. 145-147

- ^ O'Kane 1989, p. 458

- ^ Friedman through 1945, p. 297

- ^ Silverstone, p. 199

- ^ Franco, Samantha (28 July 2022). "How Veterans Saved a WWII-Era Submarine By Moving It to a Soybean Field in Oklahoma". warhistoryonline. Retrieved 23 November 2024.

- ^ "Historic Naval Sound and Video". www.maritime.org. Retrieved 23 November 2024.

- ^ "IJN Shigure: Tabular Record of Movement".

- ^ a b GUPPY and other diesel boat conversions page

- ^ Friedman 1995, p. 285

- ^ Reserve Training Boats at SubmarineSailor.com

- ^ a b Friedman since 1945, pp. 228-231

- ^ Friedman since 1945, p. 41

- ^ a b Friedman since 1945, pp. 35-43

- ^ Friedman since 1945, p. 82

- ^ Friedman since 1945, p. 37

- ^ Friedman since 1945, p. 43

- ^ Friedman since 1945, p. 253

- ^ "Whitman, Edward C. "Cold War Curiosities: U.S. Radar Picket Submarines", Undersea Warfare, Winter-Spring 2002, Issue 14". Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ^ Friedman since 1945, pp. 177-183

- ^ Friedman since 1945, pp. 86-88

- ^ Friedman since 1945, pp. 65-68

- ^ Friedman since 1945, p. 89

- ^ Museum documents an operating US, WW II built submarine in Taiwan

- ^ Jimmy Chuang (17 April 2007). "World's longest-serving sub feted". Taipei Times. p. 2.

- ^ "Muskogee War Memorial Park website". Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ "USS Becuna memorial website". Archived from the original on 3 December 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ USS Bowfin memorial website

- ^ Battleship Cove website

- ^ USS Pampanito memorial website

- ^ "Arkansas Inland Maritime Museum website". Archived from the original on 21 November 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

Bibliography

[edit]- Alden, John D. (1979). The Fleet Submarine in the U.S. Navy: A Design and Construction History. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 9780870211874.

- Friedman, Norman (1995). U.S. Submarines Through 1945: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 1-55750-263-3.

- Friedman, Norman (1994). U.S. Submarines Since 1945: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 1-55750-260-9.

- Lenton, H. T. (1973). American Submarines. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-04761-4.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1989) [1965]. U.S. Warships of World War II. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-773-9.

- Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922-1946. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-83170-303-2.

- O'Kane, Richard H. (1989). Clear the Bridge!: The War Patrols of the U.S.S. Tang. Novato, CA: Presidio Press. ISBN 978-0-89141-346-2. Different pagination than 1977 edition.

External links

[edit]- On Eternal Patrol, website for lost US subs

- A Visual Guide to the U.S. Fleet Submarines Part Five: Balao and Tench Classes 1942-1950

- Fleet Type Submarine Training Manual San Francisco Maritime Museum

- Description of GUPPY conversions at RNSubs.co.uk

- GUPPY and other diesel boat conversions page (partial archive)

- Navsource fleet submarines photo index page

- https://web.archive.org/web/20140322093118/http://www.fleetsubmarine.com/sublist.html

- DiGiulian, Tony Navweaps.com later 3"/50 caliber gun

- DiGiulian, Tony Navweaps.com 4"/50 caliber gun

- DiGiulian, Tony Navweaps.com 5"/25 caliber gun

Balao-class submarine

View on GrokipediaDesign

Specifications

The Balao-class submarines represented an evolutionary improvement over the preceding Gato-class, incorporating a strengthened pressure hull constructed from higher-tensile steel to enhance diving capabilities while maintaining similar overall dimensions and performance metrics.[7] This design allowed for greater operational depth without significantly altering displacement or speed, prioritizing reliability and crew survivability in combat environments.[8] Key physical and performance specifications of the Balao-class as originally designed are summarized below:| Category | Specification |

|---|---|

| Displacement | 1,525 long tons (1,550 t) surfaced; 2,415 long tons (2,453 t) submerged |

| Dimensions | Length: 311 ft 9 in (95.0 m); beam: 27 ft 3 in (8.3 m); draft: 16 ft 10 in (5.1 m) |

| Speed | 20.25 knots (37.5 km/h; 23.3 mph) surfaced; 8.75 knots (16.2 km/h; 10.1 mph) submerged |

| Range | 11,000 nautical miles (20,000 km; 12,000 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) surfaced |

| Crew | 80 (10 officers, 70 enlisted) |

| Test depth | 400 ft (120 m) |