Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Two-stroke engine

View on Wikipedia

A two-stroke (or two-stroke cycle) engine is a type of internal combustion engine that completes a power cycle with two strokes of the piston, one up and one down, in one revolution of the crankshaft in contrast to a four-stroke engine which requires four strokes of the piston in two crankshaft revolutions to complete a power cycle. During the stroke from bottom dead center to top dead center, the end of the exhaust/intake (or scavenging) is completed along with the compression of the mixture. The second stroke encompasses the combustion of the mixture, the expansion of the burnt mixture and, near bottom dead center, the beginning of the scavenging flows.

Two-stroke engines often have a higher power-to-weight ratio than a four-stroke engine, since their power stroke occurs twice as often. Two-stroke engines can also have fewer moving parts, and thus be cheaper to manufacture and weigh less. In countries and regions with stringent emissions regulation, two-stroke engines have been phased out in automotive and motorcycle uses. In regions where regulations are less stringent, small displacement two-stroke engines remain popular in mopeds and motorcycles.[1] They are also used in power tools such as chainsaws and leaf blowers. SSG and SLG glider planes are frequently equipped with two-stroke engines.

History

[edit]The first commercial two-stroke engine involving cylinder compression is attributed to Scottish engineer Dugald Clerk, who patented his design in 1881.[2] However, unlike most later two-stroke engines, his had a separate charging cylinder. The crankcase-scavenged engine, employing the area below the piston as a charging pump, is generally credited to Englishman Joseph Day.[3][4] On 31 December 1879, German inventor Karl Benz produced a two-stroke gas engine, for which he received a patent in 1880 in Germany. The first truly practical two-stroke engine is attributed to Yorkshireman Alfred Angas Scott, who started producing twin-cylinder water-cooled motorcycles in 1908.[5]

Two-stroke gasoline engines with electrical spark ignition are particularly useful in lightweight or portable applications such as chainsaws and motorcycles. However, when weight and size are not an issue, the cycle's potential for high thermodynamic efficiency makes it ideal for diesel compression ignition engines operating in large, weight-insensitive applications, such as marine propulsion, railway locomotives, and electricity generation. In a two-stroke engine, the exhaust gases transfer less heat to the cooling system than a four-stroke, which means more energy to drive the piston, and if present, a turbocharger.

Emissions

[edit]Crankcase-compression two-stroke engines, such as common small gasoline-powered engines, are lubricated by a petroil mixture in a total-loss system. Oil is mixed in with their petrol fuel beforehand, in a fuel-to-oil ratio of around 32:1. This oil then forms emissions, either by being burned in the engine or as droplets in the exhaust, historically resulting in more exhaust emissions, particularly hydrocarbons, than four-stroke engines of comparable power output. The combined opening time of the intake and exhaust ports in some two-stroke designs can also allow some amount of unburned fuel vapors to exit in the exhaust stream. The high combustion temperatures of small, air-cooled engines may also produce NOx emissions.

Applications

[edit]

Two-stroke gasoline engines are preferred when mechanical simplicity, light weight, and high power-to-weight ratio are design priorities. By mixing oil with fuel, they can operate in any orientation as the oil reservoir does not depend on gravity.

A number of mainstream automobile manufacturers have used two-stroke engines in the past, including the Swedish Saab, German manufacturers DKW, Auto-Union, VEB Sachsenring Automobilwerke Zwickau, VEB Automobilwerk Eisenach, and VEB Fahrzeug- und Jagdwaffenwerk, and Polish manufacturers FSO and FSM. The Japanese manufacturers Suzuki and Subaru did the same in the 1970s.[6] Production of two-stroke cars ended in the 1980s in the West, due to increasingly stringent regulation of air pollution.[7] Eastern Bloc countries continued until around 1991, with the Trabant and Wartburg in East Germany.

Two-stroke engines are still found in a variety of small propulsion applications, such as outboard motors, small on- and off-road motorcycles, mopeds, motor scooters, motorized bicycles, tuk-tuks, snowmobiles, go-karts, RC cars, ultralight and model airplanes. Particularly in developed countries, pollution regulations have meant that their use for many of these applications is being phased out. Honda,[8] for instance, ceased selling two-stroke off-road motorcycles in the United States in 2007, after abandoning road-going models considerably earlier.

Due to their high power-to-weight ratio and ability to be used in any orientation, two-stroke engines are common in handheld outdoor power tools including leaf blowers, chainsaws, and string trimmers.

Two-stroke diesel engines are found mostly in large industrial and marine applications, as well as some trucks and heavy machinery.

Designs

[edit]Although the principles remain the same, the mechanical details of various two-stroke engines differ depending on the type. The design types vary according to the method of introducing the charge to the cylinder, the method of scavenging the cylinder (exchanging burnt exhaust for fresh mixture) and the method of exhausting the cylinder.

Inlet port variations

[edit]Piston-controlled inlet port

[edit]Piston port is the simplest of the designs and the most common in small two-stroke engines. All functions are controlled solely by the piston covering and uncovering the ports as it moves up and down in the cylinder. In the 1970s, Yamaha worked out some basic principles for this system. They found that, in general, widening an exhaust port increases the power by the same amount as raising the port, but the power band does not narrow as it does when the port is raised. However, a mechanical limit exists to the width of a single exhaust port, at about 62% of the bore diameter for reasonable piston ring life. Beyond this, the piston rings bulge into the exhaust port and wear quickly. A maximum 70% of bore width is possible in racing engines, where rings are changed every few races. Intake duration is between 120 and 160°. Transfer port time is set at a minimum of 26°. The strong, low-pressure pulse of a racing two-stroke expansion chamber can drop the pressure to -7 psi when the piston is at bottom dead center, and the transfer ports nearly wide open. One of the reasons for high fuel consumption in two-strokes is that some of the incoming pressurized fuel-air mixture is forced across the top of the piston, where it has a cooling action, and straight out the exhaust pipe. An expansion chamber with a strong reverse pulse stops this outgoing flow.[9]

A fundamental difference from typical four-stroke engines is that the two-stroke's crankcase is sealed and forms part of the induction process in gasoline and hot-bulb engines. Diesel two-strokes often add a Roots blower or piston pump for scavenging.

Reed inlet valve

[edit]

The reed valve is a simple but highly effective form of check valve commonly fitted in the intake tract of the piston-controlled port. It allows asymmetric intake of the fuel charge, improving power and economy, while widening the power band. Such valves are widely used in motorcycle, ATV, and marine outboard engines.

Rotary inlet valve

[edit]The intake pathway is opened and closed by a rotating member. A familiar type sometimes seen on small motorcycles is a slotted disk attached to the crankshaft, which covers and uncovers an opening in the end of the crankcase, allowing charge to enter during one portion of the cycle (called a disc valve).

Another form of rotary inlet valve used on two-stroke engines employs two cylindrical members with suitable cutouts arranged to rotate one within the other - the inlet pipe having passage to the crankcase only when the two cutouts coincide. The crankshaft itself may form one of the members, as in most glow-plug model engines. In another version, the crank disc is arranged to be a close-clearance fit in the crankcase, and is provided with a cutout that lines up with an inlet passage in the crankcase wall at the appropriate time, as in Vespa motor scooters.

The advantage of a rotary valve is that it enables the two-stroke engine's intake timing to be asymmetrical, which is not possible with piston-port type engines. The piston-port type engine's intake timing opens and closes before and after top dead center at the same crank angle, making it symmetrical, whereas the rotary valve allows the opening to begin and close earlier.

Rotary valve engines can be tailored to deliver power over a wider speed range or higher power over a narrower speed range than either a piston-port or reed-valve engine. Where a portion of the rotary valve is a portion of the crankcase itself, of particular importance, no wear should be allowed to take place.

Scavenging variations

[edit]Cross-flow scavenging

[edit]

In a cross-flow engine, the transfer and exhaust ports are on opposite sides of the cylinder, and a deflector on the top of the piston directs the fresh intake charge into the upper part of the cylinder, pushing the residual exhaust gas down the other side of the deflector and out the exhaust port.[10] The deflector increases the piston's weight and exposed surface area, and the fact that it makes piston cooling and achieving an effective combustion chamber shape more difficult is why this design has been largely superseded by uniflow scavenging after the 1960s, especially for motorcycles, but for smaller or slower engines using direct injection, the deflector piston can still be an acceptable approach.

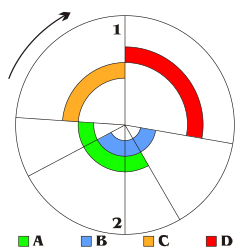

Loop scavenging

[edit]

- Top dead center (TDC)

- Bottom dead center (BDC)

This method of scavenging uses carefully shaped and positioned transfer ports to direct the flow of fresh mixture toward the combustion chamber as it enters the cylinder. The fuel/air mixture strikes the cylinder head, then follows the curvature of the combustion chamber, and then is deflected downward.

This not only prevents the fuel/air mixture from traveling directly out the exhaust port, but also creates a swirling turbulence which improves combustion efficiency, power, and economy. Usually, a piston deflector is not required, so this approach has a distinct advantage over the cross-flow scheme (above).

Often referred to as "Schnuerle" (or "Schnürle") loop scavenging after Adolf Schnürle, the German inventor of an early form in the mid-1920s, it became widely adopted in Germany during the 1930s and spread further afield after World War II.

Loop scavenging is the most common type of fuel/air mixture transfer used on modern two-stroke engines. Suzuki was one of the first manufacturers outside of Europe to adopt loop-scavenged two-stroke engines. This operational feature was used in conjunction with the expansion chamber exhaust developed by German motorcycle manufacturer, MZ, and Walter Kaaden.

Loop scavenging, disc valves, and expansion chambers worked in a highly coordinated way to significantly increase the power output of two-stroke engines, particularly from the Japanese manufacturers Suzuki, Yamaha, and Kawasaki. Suzuki and Yamaha enjoyed success in Grand Prix motorcycle racing in the 1960s due in no small way to the increased power afforded by loop scavenging.

An additional benefit of loop scavenging was the piston could be made nearly flat or slightly domed, which allowed the piston to be appreciably lighter and stronger, and consequently to tolerate higher engine speeds. The "flat top" piston also has better thermal properties and is less prone to uneven heating, expansion, piston seizures, dimensional changes, and compression losses.

SAAB built 750- and 850-cc three-cylinder engines based on a DKW design that proved reasonably successful employing loop charging. The original SAAB 92 had a two-cylinder engine of comparatively low efficiency. At cruising speed, reflected-wave, exhaust-port blocking occurred at too low a frequency. Using the asymmetrical three-port exhaust manifold employed in the identical DKW engine improved fuel economy.

The 750-cc standard engine produced 36 to 42 hp, depending on the model year. The Monte Carlo Rally variant, 750-cc (with a filled crankshaft for higher base compression), generated 65 hp. An 850-cc version was available in the 1966 SAAB Sport (a standard trim model in comparison to the deluxe trim of the Monte Carlo). Base compression comprises a portion of the overall compression ratio of a two-stroke engine. Work published at SAE in 2012 points that loop scavenging is under every circumstance more efficient than cross-flow scavenging.

Uniflow scavenging

[edit]-

Two-stroke diesel uniflow engine animation

-

Uniflow scavenging flow schematic

- Top dead center (TDC)

- Bottom dead center (BDC)

In a uniflow engine, the mixture, or "charge air" in the case of a diesel, enters at one end of the cylinder controlled by the piston and the exhaust exits at the other end controlled by an exhaust valve or piston. The scavenging gas-flow is, therefore, in one direction only, hence the name uniflow.

The design using exhaust valve(s) is common in on-road, off-road, and stationary two-stroke engines (Detroit Diesel), certain small marine two-stroke engines (Gray Marine Motor Company, which adapted the Detroit Diesel Series 71 for marine use), certain railroad two-stroke diesel locomotives (Electro-Motive Diesel) and large marine two-stroke main propulsion engines (Wärtsilä). Ported types are represented by the opposed piston design in which two pistons are in each cylinder, working in opposite directions such as the Junkers Jumo 205 and Napier Deltic.[11] The once-popular split-single design falls into this class, being effectively a folded uniflow. With advanced-angle exhaust timing, uniflow engines can be supercharged with a crankshaft-driven blower, either piston or Roots-type.[12][13]

Stepped piston engine

[edit]The piston of this engine is "top-hat"-shaped; the upper section forms the regular cylinder, and the lower section performs a scavenging function. The units run in pairs, with the lower half of one piston charging an adjacent combustion chamber.

The upper section of the piston still relies on total-loss lubrication, but the other engine parts are sump lubricated with cleanliness and reliability benefits. The mass of the piston is only about 20% more than a loop-scavenged engine's piston because skirt thicknesses can be less.[14]

Power-valve systems

[edit]Many modern two-stroke engines employ a power-valve system. The valves are normally in or around the exhaust ports. They work in one of two ways; either they alter the exhaust port by closing off the top part of the port, which alters port timing, such as Rotax R.A.V.E, Yamaha YPVS, Honda RC-Valve, Kawasaki K.I.P.S., Cagiva C.T.S., or Suzuki AETC systems, or by altering the volume of the exhaust, which changes the resonant frequency of the expansion chamber, such as the Suzuki SAEC and Honda V-TACS system. The result is an engine with better low-speed power without sacrificing high-speed power. However, as power valves are in the hot gas flow, they need regular maintenance to perform well.

Direct injection

[edit]Direct injection has considerable advantages in two-stroke engines. In carburetted two-strokes, a major problem is a portion of the fuel/air mixture going directly out, unburned, through the exhaust port, and direct injection effectively eliminates this problem. Two systems are in use: low-pressure air-assisted injection and high-pressure injection.

Since the fuel does not pass through the crankcase, a separate source of lubrication is needed.

Two-stroke reversibility

[edit]For the purpose of this discussion, it is convenient to think in motorcycle terms, where the exhaust pipe faces into the cooling air stream, and the crankshaft commonly spins in the same axis and direction as do the wheels i.e. "forward". Some of the considerations discussed here apply to four-stroke engines (which cannot reverse their direction of rotation without considerable modification), almost all of which spin forward, too. It is also useful to note that the "front" and "back" faces of the piston are - respectively - the exhaust port and intake port sides of it, and are not to do with the top or bottom of the piston.

Regular gasoline two-stroke engines can run backward for short periods and under light load with little problem, and this has been used to provide a reversing facility in microcars, such as the Messerschmitt KR200, that lacked reverse gearing. Where the vehicle has electric starting, the motor is turned off and restarted backward by turning the key in the opposite direction. Two-stroke golf carts have used a similar system. Traditional flywheel magnetos (using contact-breaker points, but no external coil) worked equally well in reverse because the cam controlling the points is symmetrical, breaking contact before top dead center equally well whether running forward or backward. Reed-valve engines run backward just as well as piston-controlled porting, though rotary valve engines have asymmetrical inlet timing and do not run very well.

Serious disadvantages exist for running many engines backward under load for any length of time, and some of these reasons are general, applying equally to both two-stroke and four-stroke engines. This disadvantage is accepted in most cases where cost, weight, and size are major considerations. The problem comes about because in "forward" running, the major thrust face of the piston is on the back face of the cylinder, which in a two-stroke particularly, is the coolest and best-lubricated part. The forward face of the piston in a trunk engine is less well-suited to be the major thrust face, since it covers and uncovers the exhaust port in the cylinder, the hottest part of the engine, where piston lubrication is at its most marginal. The front face of the piston is also more vulnerable since the exhaust port, the largest in the engine, is in the front wall of the cylinder. Piston skirts and rings risk being extruded into this port, so having them pressing hardest on the opposite wall (where there are only the transfer ports in a crossflow engine) is always best and support is good. In some engines, the small end is offset to reduce thrust in the intended rotational direction and the forward face of the piston has been made thinner and lighter to compensate, but when running backward, this weaker forward face suffers increased mechanical stress it was not designed to resist.[15] This can be avoided by the use of crossheads and also using thrust bearings to isolate the engine from end loads.

Large two-stroke ship diesels are sometimes made to be reversible. Like four-stroke ship engines (some of which are also reversible), they use mechanically operated valves, so require additional camshaft mechanisms. These engines use crossheads to eliminate sidethrust on the piston and isolate the under-piston space from the crankcase.

On top of other considerations, the oil pump of a modern two-stroke may not work in reverse, in which case the engine suffers oil starvation within a short time. Running a motorcycle engine backward is relatively easy to initiate, and in rare cases, can be triggered by a back-fire.[citation needed] It is not advisable.

Model airplane engines with reed valves can be mounted in either tractor or pusher configuration without needing to change the propeller. These motors are compression ignition, so no ignition timing issues and little difference between running forward and running backward are seen.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Docker Maroc" (in French). Retrieved 2023-04-12.

- ^ See:

- Clerk, Dugald; English patent no. 1,089 (issued: March 14, 1881).

- Clerk, Dugald "Motor worked by combustible gas or vapor," U.S. patent no. 249,307 (filed: September 2, 1881; issued: November 8, 1881).

- ^ See:

- Day, Joseph; British patent no. 6,410 (issued: April 14, 1891).

- Day, Joseph; British patent no. 9,247 (issued: July 1, 1891).

- Day, Joseph "Gas-engine" US patent no. 543,614 (filed: May 21, 1892; issued: July 30, 1895).

- Torrens, Hugh S. (May 1992). "A study of 'failure' with a 'successful innovation': Joseph Day and the two-stroke internal combustion engine". Social Studies of Science. 22 (2): 245–262. doi:10.1177/030631292022002004. S2CID 110285769.

- ^ Joseph Day's engine used a reed valve. One of Day's employees, Frederic Cock (1863–1944), found a way to render the engine completely valve-less. See:

- Cock, Frederic William Caswell; British patent no. 18,513 (issued: October 15, 1892).

- Cock, Frederic William Caswell "Gas-engine" US patent no. 544,210 (filed: March 10, 1894; issued: August 6, 1895).

- The Day-Cock engine is illustrated in: Dowson, Joseph Emerson (1893). "Gas-power for electric lighting: Discussion". Minutes of Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers. 112: 2–110. doi:10.1680/imotp.1893.20024.; see p. 48.

- ^ Clew, Jeff (2004). The Scott Motorcycle: The Yowling Two-Stroke. Haynes Publishing. p. 240. ISBN 0854291644.

- ^ "Suzuki LJ50 INFO". Lj10.com. Retrieved 2010-11-07.

- ^ US EPA, OAR (16 August 2016). "Vehicles and Engines". US EPA.

- ^ "Two-Stroke Tuesday | 2007 Honda CR125". Motocross Action magazine. 25 September 2018. Archived from the original on 2021-11-19. Retrieved 2021-11-19.

- ^ Jennings, Gordon (January 1973). "Port timing". Two-stroke Tuner's Handbook (PDF). pp. 75–90. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ Irving, P.E. (1967). Two-Stroke Power Units. Newnes. pp. 13–15.

- ^ "junkers". Iet.aau.dk. Archived from the original on May 1, 2008. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ^ McCutcheon, Kimble D. (1 August 2022). "Selected Early Engines: Junkers". Engine History. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

Junkers built experimental two-stroke opposed-piston diesel aircraft engines during WWI, which were derived from a stationary engine line. These featured two crankshafts at the cylinder ends connected by a gear train that also drove the propeller. Two pistons, working in opposite directions in each cylinder, uncovered inlet and exhaust ports near the ends of their strokes. The exhaust port was uncovered first, and when the inlet port was uncovered, a compressed air charge was forced through the cylinders, practically clearing all burnt gases.

- ^ "Junkers Jumo 207 D-V2 In-line 6 Diesel Engine". National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ "Stepped-Piston Engines - BASIC DESIGN PARAMETERS 3.1 Engine and Port Geometry".

- ^ Ross and Ungar, "On Piston Slap as a Source of Engine Noise," ASME Paper

Further reading

[edit]- Frank Jardine (Alcoa): "Thermal Expansion in Automotive-Engine Design", SAE paper 300010

- G P Blair et al. (Univ of Belfast), R Fleck (Mercury Marine), "Predicting the Performance Characteristics of Two-Cycle Engines Fitted with Reed Induction Valves", SAE paper 790842

- G Bickle et al. (ICT Co), R Domesle et al. (Degussa AG): "Controlling Two-Stroke Engine Emissions", Automotive Engineering International (SAE) Feb 2000:27-32.

- BOSCH, "Automotive Manual", 2005, Section: Fluid's Mechanics, Table 'Discharge from High-Pressure Deposits'.

External links

[edit] Media related to Two-stroke engines at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Two-stroke engines at Wikimedia Commons- Two-Stroke Engine at How Stuff Works

- Sherman, Don (December 17, 2009), "A Two-Stroke Revival, Without the Blue Haze", The New York Times.

Two-stroke engine

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Operating Principle

A two-stroke engine completes a thermodynamic cycle in two piston strokes, equivalent to one crankshaft revolution, producing one power stroke per revolution.[9] This contrasts with four-stroke engines, which require four strokes or two revolutions for a power stroke.[10] In typical crankcase-scavenged designs, the engine lacks valves, relying instead on ports in the cylinder wall uncovered by piston movement to manage intake, transfer, and exhaust processes.[11] The cycle integrates compression, power, exhaust, and intake phases across the upstroke and downstroke. During the upward piston stroke, the space above the piston undergoes compression of the air-fuel mixture, while the crankcase below experiences reduced pressure, drawing in fresh mixture through an inlet port or reed valve.[12] At top dead center, ignition occurs via spark plug, initiating the power stroke as expanding gases drive the piston downward.[13] This downward motion pressurizes the crankcase mixture, which awaits transfer. As the piston descends further, it first exposes the exhaust port near bottom dead center, releasing high-pressure burnt gases to atmosphere, aided by exhaust tuning in some designs.[10] Subsequently, the piston uncovers transfer ports, allowing the pressurized crankcase mixture to enter the cylinder at an angle, facilitating scavenging—the displacement of residual exhaust gases by incoming charge.[14] Effective scavenging, quantified by delivery ratio and trapping efficiency, is critical, as incomplete removal leads to charge dilution and reduced power density.[15] Common methods include loop scavenging, where transfer ports direct flow to loop around the cylinder, and cross-flow scavenging with deflector pistons, though uniflow scavenging in larger engines uses opposed ports and separate blowers for superior efficiency.[16] Lubrication occurs via oil mixed in the fuel, as the crankcase handles combustible mixture.[17] This principle enables higher power-to-weight ratios but sacrifices fuel efficiency due to potential short-circuiting of fresh charge during scavenging.[18]Comparison to Four-Stroke Engines

Two-stroke engines complete a power cycle in one crankshaft revolution, firing once per revolution, whereas four-stroke engines require two revolutions for a power stroke every other revolution.[3][19] This fundamental difference results in two-stroke engines delivering approximately twice the power output per unit of displacement compared to four-stroke engines of equivalent size, enabling higher power-to-weight ratios suitable for applications like portable tools and lightweight vehicles.[3][20] However, this comes at the cost of efficiency, as two-stroke engines suffer from incomplete scavenging, where fresh air-fuel mixture mixes with exhaust gases, leading to reduced volumetric efficiency and higher fuel consumption.[21][22] Four-stroke engines achieve higher thermal efficiency, typically 20-30% greater than two-stroke designs in comparable small gasoline applications, due to dedicated intake and exhaust strokes that minimize charge loss and enable better combustion control.[23][21] In two-stroke operation, the reliance on piston-controlled ports and crankcase compression often results in 10-20% of the incoming charge escaping unburned through exhaust ports, exacerbating fuel waste.[24] Four-stroke engines also separate lubrication from fuel, using an oil sump system that reduces wear and allows cleaner operation without oil-fuel premixing, which in two-strokes contributes to carbon buildup and shorter lifespan.[4][25] Emissions profiles differ markedly: two-stroke engines emit higher levels of hydrocarbons and particulate matter—often 2-5 times more than four-strokes—owing to oil burning and short-circuiting of unburned mixture during scavenging.[24][26] Four-stroke engines, with valves enabling timed exhaust clearance and after-treatment compatibility, produce lower unburned hydrocarbons and nitrogen oxides in regulated applications. Mechanically, two-strokes feature fewer components (no camshaft or valves), reducing weight by up to 30% and simplifying maintenance for intermittent use, though they demand frequent rebuilds due to lubrication challenges.[27][28]| Aspect | Two-Stroke Advantage/Disadvantage | Four-Stroke Advantage/Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|

| Power Density | Higher (twice per revolution) | Lower per displacement |

| Thermal Efficiency | Lower (scavenging losses) | Higher (complete cycles) |

| Weight/Complexity | Lighter, simpler design | Heavier, more parts |

| Emissions | Higher pollutants | Lower, cleaner combustion |

| Fuel Consumption | Higher per power output | Lower overall |