Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Binary logarithm

View on Wikipedia

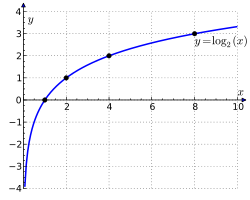

In mathematics, the binary logarithm (log2 n) is the power to which the number 2 must be raised to obtain the value n. That is, for any real number x,

For example, the binary logarithm of 1 is 0, the binary logarithm of 2 is 1, the binary logarithm of 4 is 2, and the binary logarithm of 32 is 5.

The binary logarithm is the logarithm to the base 2 and is the inverse function of the power of two function. There are several alternatives to the log2 notation for the binary logarithm; see the Notation section below.

Historically, the first application of binary logarithms was in music theory, by Leonhard Euler: the binary logarithm of a frequency ratio of two musical tones gives the number of octaves by which the tones differ. Binary logarithms can be used to calculate the length of the representation of a number in the binary numeral system, or the number of bits needed to encode a message in information theory. In computer science, they count the number of steps needed for binary search and related algorithms. Other areas in which the binary logarithm is frequently used include combinatorics, bioinformatics, the design of sports tournaments, and photography.

Binary logarithms are included in the standard C mathematical functions and other mathematical software packages.

History

[edit]

The powers of two have been known since antiquity; for instance, they appear in Euclid's Elements, Props. IX.32 (on the factorization of powers of two) and IX.36 (half of the Euclid–Euler theorem, on the structure of even perfect numbers). And the binary logarithm of a power of two is just its position in the ordered sequence of powers of two. On this basis, Michael Stifel has been credited with publishing the first known table of binary logarithms in 1544. His book Arithmetica Integra contains several tables that show the integers with their corresponding powers of two. Reversing the rows of these tables allow them to be interpreted as tables of binary logarithms.[1][2]

Earlier than Stifel, the 8th century Jain mathematician Virasena is credited with a precursor to the binary logarithm. Virasena's concept of ardhacheda has been defined as the number of times a given number can be divided evenly by two. This definition gives rise to a function that coincides with the binary logarithm on the powers of two,[3] but it is different for other integers, giving the 2-adic order rather than the logarithm.[4]

The modern form of a binary logarithm, applying to any number (not just powers of two) was considered explicitly by Leonhard Euler in 1739. Euler established the application of binary logarithms to music theory, long before their applications in information theory and computer science became known. As part of his work in this area, Euler published a table of binary logarithms of the integers from 1 to 8, to seven decimal digits of accuracy.[5][6]

Definition and properties

[edit]The binary logarithm function may be defined as the inverse function to the power of two function, which is a strictly increasing function over the positive real numbers and therefore has a unique inverse.[7] Alternatively, it may be defined as ln n / ln 2, where ln is the natural logarithm, defined in any of its standard ways. Using the complex logarithm in this definition allows the binary logarithm to be extended to the complex numbers.[8]

As with other logarithms, the binary logarithm obeys the following equations, which can be used to simplify formulas that combine binary logarithms with multiplication or exponentiation:[9]

For more, see list of logarithmic identities.

Notation

[edit]In mathematics, the binary logarithm of a number n is often written as log2 n.[10] However, several other notations for this function have been used or proposed, especially in application areas.

Some authors write the binary logarithm as lg n,[11][12] the notation listed in The Chicago Manual of Style.[13] Donald Knuth credits this notation to a suggestion of Edward Reingold,[14] but its use in both information theory and computer science dates to before Reingold was active.[15][16] The binary logarithm has also been written as log n with a prior statement that the default base for the logarithm is 2.[17][18][19] Another notation that is often used for the same function (especially in the German scientific literature) is ld n,[20][21][22] from Latin logarithmus dualis[20] or logarithmus dyadis.[20] The DIN 1302, ISO 31-11 and ISO 80000-2 standards recommend yet another notation, lb n. According to these standards, lg n should not be used for the binary logarithm, as it is instead reserved for the common logarithm log10 n.[23][24][25]

Applications

[edit]Information theory

[edit]The number of digits (bits) in the binary representation of a positive integer n is the integral part of 1 + log2 n, i.e.[12]

In information theory, the definition of the amount of self-information and information entropy is often expressed with the binary logarithm, corresponding to making the bit the fundamental unit of information. With these units, the Shannon–Hartley theorem expresses the information capacity of a channel as the binary logarithm of its signal-to-noise ratio, plus one. However, the natural logarithm and the nat are also used in alternative notations for these definitions.[26]

Combinatorics

[edit]

Although the natural logarithm is more important than the binary logarithm in many areas of pure mathematics such as number theory and mathematical analysis,[27] the binary logarithm has several applications in combinatorics:

- Every binary tree with n leaves has height at least log2 n, with equality when n is a power of two and the tree is a complete binary tree.[28] Relatedly, the Strahler number of a river system with n tributary streams is at most log2 n + 1.[29]

- Every family of sets with n different sets has at least log2 n elements in its union, with equality when the family is a power set.[30]

- Every partial cube with n vertices has isometric dimension at least log2 n, and has at most 1/2 n log2 n edges, with equality when the partial cube is a hypercube graph.[31]

- According to Ramsey's theorem, every n-vertex undirected graph has either a clique or an independent set of size logarithmic in n. The precise size that can be guaranteed is not known, but the best bounds known on its size involve binary logarithms. In particular, all graphs have a clique or independent set of size at least 1/2 log2 n (1 − o(1)) and almost all graphs do not have a clique or independent set of size larger than 2 log2 n (1 + o(1)).[32]

- From a mathematical analysis of the Gilbert–Shannon–Reeds model of random shuffles, one can show that the number of times one needs to shuffle an n-card deck of cards, using riffle shuffles, to get a distribution on permutations that is close to uniformly random, is approximately 3/2 log2 n. This calculation forms the basis for a recommendation that 52-card decks should be shuffled seven times.[33]

Computational complexity

[edit]

The binary logarithm also frequently appears in the analysis of algorithms,[19] not only because of the frequent use of binary number arithmetic in algorithms, but also because binary logarithms occur in the analysis of algorithms based on two-way branching.[14] If a problem initially has n choices for its solution, and each iteration of the algorithm reduces the number of choices by a factor of two, then the number of iterations needed to select a single choice is again the integral part of log2 n. This idea is used in the analysis of several algorithms and data structures. For example, in binary search, the size of the problem to be solved is halved with each iteration, and therefore roughly log2 n iterations are needed to obtain a solution for a problem of size n.[34] Similarly, a perfectly balanced binary search tree containing n elements has height log2(n + 1) − 1.[35]

The running time of an algorithm is usually expressed in big O notation, which is used to simplify expressions by omitting their constant factors and lower-order terms. Because logarithms in different bases differ from each other only by a constant factor, algorithms that run in O(log2 n) time can also be said to run in, say, O(log13 n) time. The base of the logarithm in expressions such as O(log n) or O(n log n) is therefore not important and can be omitted.[11][36] However, for logarithms that appear in the exponent of a time bound, the base of the logarithm cannot be omitted. For example, O(2log2 n) is not the same as O(2ln n) because the former is equal to O(n) and the latter to O(n0.6931...).

Algorithms with running time O(n log n) are sometimes called linearithmic.[37] Some examples of algorithms with running time O(log n) or O(n log n) are:

- Average time quicksort and other comparison sort algorithms[38]

- Searching in balanced binary search trees[39]

- Exponentiation by squaring[40]

- Longest increasing subsequence[41]

Binary logarithms also occur in the exponents of the time bounds for some divide and conquer algorithms, such as the Karatsuba algorithm for multiplying n-bit numbers in time O(nlog2 3),[42] and the Strassen algorithm for multiplying n × n matrices in time O(nlog2 7).[43] The occurrence of binary logarithms in these running times can be explained by reference to the master theorem for divide-and-conquer recurrences.

Bioinformatics

[edit]

In bioinformatics, microarrays are used to measure how strongly different genes are expressed in a sample of biological material. Different rates of expression of a gene are often compared by using the binary logarithm of the ratio of expression rates: the log ratio of two expression rates is defined as the binary logarithm of the ratio of the two rates. Binary logarithms allow for a convenient comparison of expression rates: a doubled expression rate can be described by a log ratio of 1, a halved expression rate can be described by a log ratio of −1, and an unchanged expression rate can be described by a log ratio of zero, for instance.[44]

Data points obtained in this way are often visualized as a scatterplot in which one or both of the coordinate axes are binary logarithms of intensity ratios, or in visualizations such as the MA plot and RA plot that rotate and scale these log ratio scatterplots.[45]

Music theory

[edit]In music theory, the interval or perceptual difference between two tones is determined by the ratio of their frequencies. Intervals coming from rational number ratios with small numerators and denominators are perceived as particularly euphonious. The simplest and most important of these intervals is the octave, a frequency ratio of 2:1. The number of octaves by which two tones differ is the binary logarithm of their frequency ratio.[46]

To study tuning systems and other aspects of music theory that require finer distinctions between tones, it is helpful to have a measure of the size of an interval that is finer than an octave and is additive (as logarithms are) rather than multiplicative (as frequency ratios are). That is, if tones x, y, and z form a rising sequence of tones, then the measure of the interval from x to y plus the measure of the interval from y to z should equal the measure of the interval from x to z. Such a measure is given by the cent, which divides the octave into 1200 equal intervals (12 semitones of 100 cents each). Mathematically, given tones with frequencies f1 and f2, the number of cents in the interval from f1 to f2 is[46]

The millioctave is defined in the same way, but with a multiplier of 1000 instead of 1200.[47]

Sports scheduling

[edit]In competitive games and sports involving two players or teams in each game or match, the binary logarithm indicates the number of rounds necessary in a single-elimination tournament required to determine a winner. For example, a tournament of 4 players requires log2 4 = 2 rounds to determine the winner, a tournament of 32 teams requires log2 32 = 5 rounds, etc. In this case, for n players/teams where n is not a power of 2, log2 n is rounded up since it is necessary to have at least one round in which not all remaining competitors play. For example, log2 6 is approximately 2.585, which rounds up to 3, indicating that a tournament of 6 teams requires 3 rounds (either two teams sit out the first round, or one team sits out the second round). The same number of rounds is also necessary to determine a clear winner in a Swiss-system tournament.[48]

Photography

[edit]In photography, exposure values are measured in terms of the binary logarithm of the amount of light reaching the film or sensor, in accordance with the Weber–Fechner law describing a logarithmic response of the human visual system to light. A single stop of exposure is one unit on a base-2 logarithmic scale.[49][50] More precisely, the exposure value of a photograph is defined as

where N is the f-number measuring the aperture of the lens during the exposure, and t is the number of seconds of exposure.[51]

Binary logarithms (expressed as stops) are also used in densitometry, to express the dynamic range of light-sensitive materials or digital sensors.[52]

Calculation

[edit]

Conversion from other bases

[edit]An easy way to calculate log2 n on calculators that do not have a log2 function is to use the natural logarithm (ln) or the common logarithm (log or log10) functions, which are found on most scientific calculators. To change the logarithm base to 2 from e, 10, or any other base b, one can use the formulae:[50][53]

Integer rounding

[edit]The binary logarithm can be made into a function from integers and to integers by rounding it up or down. These two forms of integer binary logarithm are related by this formula:

The definition can be extended by defining . Extended in this way, this function is related to the number of leading zeros of the 32-bit unsigned binary representation of x, nlz(x).

The integer binary logarithm can be interpreted as the zero-based index of the most significant 1 bit in the input. In this sense it is the complement of the find first set operation, which finds the index of the least significant 1 bit. Many hardware platforms include support for finding the number of leading zeros, or equivalent operations, which can be used to quickly find the binary logarithm. The fls and flsl functions in the Linux kernel[57] and in some versions of the libc software library also compute the binary logarithm (rounded up to an integer, plus one).

Piecewise-linear approximation

[edit]For a number represented in floating point as , with integer exponent and mantissa in the range , the binary logarithm can be roughly approximated as .[16] This approximation is exact at both ends of the range of mantissas but underestimates the logarithm in the middle of the range, reaching a maximum error of approximately 0.086 at a mantissa of approximately 0.44. It can be made more accurate by using a piecewise linear function of ,[58] or more crudely by adding a constant correction term . For instance choosing would halve the maximum error. The fast inverse square root algorithm uses this idea, with a different correction term that can be inferred to be , by directly manipulating the binary representation of to multiply this approximate logarithm by , obtaining a floating point value that approximates .[59]

Iterative approximation

[edit]For a general positive real number, the binary logarithm may be computed in two parts.[60] First, one computes the integer part, (called the characteristic of the logarithm). This reduces the problem to one where the argument of the logarithm is in a restricted range, the interval [1, 2), simplifying the second step of computing the fractional part (the mantissa of the logarithm). For any x > 0, there exists a unique integer n such that 2n ≤ x < 2n+1, or equivalently 1 ≤ 2−nx < 2. Now the integer part of the logarithm is simply n, and the fractional part is log2(2−nx).[60] In other words:

For normalized floating-point numbers, the integer part is given by the floating-point exponent,[61] and for integers it can be determined by performing a count leading zeros operation.[62]

The fractional part of the result is log2 y and can be computed iteratively, using only elementary multiplication and division.[60] The algorithm for computing the fractional part can be described in pseudocode as follows:

- Start with a real number y in the half-open interval [1, 2). If y = 1, then the algorithm is done, and the fractional part is zero.

- Otherwise, square y repeatedly until the result z lies in the interval [2, 4). Let m be the number of squarings needed. That is, z = y2m with m chosen such that z is in [2, 4).

- Taking the logarithm of both sides and doing some algebra:

- Once again z/2 is a real number in the interval [1, 2). Return to step 1 and compute the binary logarithm of z/2 using the same method.

The result of this is expressed by the following recursive formulas, in which is the number of squarings required in the i-th iteration of the algorithm:

In the special case where the fractional part in step 1 is found to be zero, this is a finite sequence terminating at some point. Otherwise, it is an infinite series that converges according to the ratio test, since each term is strictly less than the previous one (since every mi > 0). See Horner's method. For practical use, this infinite series must be truncated to reach an approximate result. If the series is truncated after the i-th term, then the error in the result is less than 2−(m1 + m2 + ⋯ + mi).[60]

Software library support

[edit]The log2 function is included in the standard C mathematical functions. The default version of this function takes double precision arguments but variants of it allow the argument to be single-precision or to be a long double.[63] In computing environments supporting complex numbers and implicit type conversion such as MATLAB the argument to the log2 function is allowed to be a negative number, returning a complex one.[64]

References

[edit]- ^ Groza, Vivian Shaw; Shelley, Susanne M. (1972), Precalculus mathematics, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, p. 182, ISBN 978-0-03-077670-0.

- ^ Stifel, Michael (1544), Arithmetica integra (in Latin), p. 31. A copy of the same table with two more entries appears on p. 237, and another copy extended to negative powers appears on p. 249b.

- ^ Joseph, G. G. (2011), The Crest of the Peacock: Non-European Roots of Mathematics (3rd ed.), Princeton University Press, p. 352.

- ^ See, e.g., Shparlinski, Igor (2013), Cryptographic Applications of Analytic Number Theory: Complexity Lower Bounds and Pseudorandomness, Progress in Computer Science and Applied Logic, vol. 22, Birkhäuser, p. 35, ISBN 978-3-0348-8037-4.

- ^ Euler, Leonhard (1739), "Chapter VII. De Variorum Intervallorum Receptis Appelationibus", Tentamen novae theoriae musicae ex certissismis harmoniae principiis dilucide expositae (in Latin), Saint Petersburg Academy, pp. 102–112.

- ^ Tegg, Thomas (1829), "Binary logarithms", London encyclopaedia; or, Universal dictionary of science, art, literature and practical mechanics: comprising a popular view of the present state of knowledge, Volume 4, pp. 142–143.

- ^ Batschelet, E. (2012), Introduction to Mathematics for Life Scientists, Springer, p. 128, ISBN 978-3-642-96080-2.

- ^ For instance, Microsoft Excel provides the

IMLOG2function for complex binary logarithms: see Bourg, David M. (2006), Excel Scientific and Engineering Cookbook, O'Reilly Media, p. 232, ISBN 978-0-596-55317-3. - ^ Kolman, Bernard; Shapiro, Arnold (1982), "11.4 Properties of Logarithms", Algebra for College Students, Academic Press, pp. 334–335, ISBN 978-1-4832-7121-7.

- ^ For instance, this is the notation used in the Encyclopedia of Mathematics and The Princeton Companion to Mathematics.

- ^ a b Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L.; Stein, Clifford (2001) [1990], Introduction to Algorithms (2nd ed.), MIT Press and McGraw-Hill, pp. 34, 53–54, ISBN 0-262-03293-7

- ^ a b Sedgewick, Robert; Wayne, Kevin Daniel (2011), Algorithms, Addison-Wesley Professional, p. 185, ISBN 978-0-321-57351-3.

- ^ The Chicago Manual of Style (25th ed.), University of Chicago Press, 2003, p. 530.

- ^ a b Knuth, Donald E. (1997), Fundamental Algorithms, The Art of Computer Programming, vol. 1 (3rd ed.), Addison-Wesley Professional, ISBN 978-0-321-63574-7, p. 11. The same notation was in the 1973 2nd edition of the same book (p. 23) but without the credit to Reingold.

- ^ Trucco, Ernesto (1956), "A note on the information content of graphs", Bull. Math. Biophys., 18 (2): 129–135, doi:10.1007/BF02477836, MR 0077919.

- ^ a b Mitchell, John N. (1962), "Computer multiplication and division using binary logarithms", IRE Transactions on Electronic Computers, EC-11 (4): 512–517, Bibcode:1962IRTEC..11..512M, doi:10.1109/TEC.1962.5219391.

- ^ Fiche, Georges; Hebuterne, Gerard (2013), Mathematics for Engineers, John Wiley & Sons, p. 152, ISBN 978-1-118-62333-6,

In the following, and unless otherwise stated, the notation log x always stands for the logarithm to the base 2 of x

. - ^ Cover, Thomas M.; Thomas, Joy A. (2012), Elements of Information Theory (2nd ed.), John Wiley & Sons, p. 33, ISBN 978-1-118-58577-1,

Unless otherwise specified, we will take all logarithms to base 2

. - ^ a b Goodrich, Michael T.; Tamassia, Roberto (2002), Algorithm Design: Foundations, Analysis, and Internet Examples, John Wiley & Sons, p. 23,

One of the interesting and sometimes even surprising aspects of the analysis of data structures and algorithms is the ubiquitous presence of logarithms ... As is the custom in the computing literature, we omit writing the base b of the logarithm when b = 2.

- ^ a b c Tafel, Hans Jörg (1971), Einführung in die digitale Datenverarbeitung [Introduction to digital information processing] (in German), Munich: Carl Hanser Verlag, pp. 20–21, ISBN 3-446-10569-7

- ^ Tietze, Ulrich; Schenk, Christoph (1999), Halbleiter-Schaltungstechnik (in German) (1st corrected reprint, 11th ed.), Springer Verlag, p. 1370, ISBN 3-540-64192-0

- ^ Bauer, Friedrich L. (2009), Origins and Foundations of Computing: In Cooperation with Heinz Nixdorf MuseumsForum, Springer Science & Business Media, p. 54, ISBN 978-3-642-02991-2.

- ^ For DIN 1302 see Brockhaus Enzyklopädie in zwanzig Bänden [Brockhaus Encyclopedia in Twenty Volumes] (in German), vol. 11, Wiesbaden: F.A. Brockhaus, 1970, p. 554, ISBN 978-3-7653-0000-4.

- ^ For ISO 31-11 see Thompson, Ambler; Taylor, Barry M (March 2008), Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) — NIST Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition — Second Printing (PDF), NIST, p. 33.

- ^ For ISO 80000-2 see "Quantities and units – Part 2: Mathematical signs and symbols to be used in the natural sciences and technology" (PDF), International Standard ISO 80000-2 (1st ed.), December 1, 2009, Section 12, Exponential and logarithmic functions, p. 18.

- ^ Van der Lubbe, Jan C. A. (1997), Information Theory, Cambridge University Press, p. 3, ISBN 978-0-521-46760-5.

- ^ Stewart, Ian (2015), Taming the Infinite, Quercus, p. 120, ISBN 9781623654733,

in advanced mathematics and science the only logarithm of importance is the natural logarithm

. - ^ Leiss, Ernst L. (2006), A Programmer's Companion to Algorithm Analysis, CRC Press, p. 28, ISBN 978-1-4200-1170-8.

- ^ Devroye, L.; Kruszewski, P. (1996), "On the Horton–Strahler number for random tries", RAIRO Informatique Théorique et Applications, 30 (5): 443–456, doi:10.1051/ita/1996300504431, MR 1435732.

- ^ Equivalently, a family with k distinct elements has at most 2k distinct sets, with equality when it is a power set.

- ^ Eppstein, David (2005), "The lattice dimension of a graph", European Journal of Combinatorics, 26 (5): 585–592, arXiv:cs.DS/0402028, doi:10.1016/j.ejc.2004.05.001, MR 2127682, S2CID 7482443.

- ^ Graham, Ronald L.; Rothschild, Bruce L.; Spencer, Joel H. (1980), Ramsey Theory, Wiley-Interscience, p. 78.

- ^ Bayer, Dave; Diaconis, Persi (1992), "Trailing the dovetail shuffle to its lair", The Annals of Applied Probability, 2 (2): 294–313, doi:10.1214/aoap/1177005705, JSTOR 2959752, MR 1161056.

- ^ Mehlhorn, Kurt; Sanders, Peter (2008), "2.5 An example – binary search", Algorithms and Data Structures: The Basic Toolbox (PDF), Springer, pp. 34–36, ISBN 978-3-540-77977-3.

- ^ Roberts, Fred; Tesman, Barry (2009), Applied Combinatorics (2nd ed.), CRC Press, p. 206, ISBN 978-1-4200-9983-6.

- ^ Sipser, Michael (2012), "Example 7.4", Introduction to the Theory of Computation (3rd ed.), Cengage Learning, pp. 277–278, ISBN 9781133187790.

- ^ Sedgewick & Wayne (2011), p. 186.

- ^ Cormen et al. (2001), p. 156; Goodrich & Tamassia (2002), p. 238.

- ^ Cormen et al. (2001), p. 276; Goodrich & Tamassia (2002), p. 159.

- ^ Cormen et al. (2001), p. 879–880; Goodrich & Tamassia (2002), p. 464.

- ^ Edmonds, Jeff (2008), How to Think About Algorithms, Cambridge University Press, p. 302, ISBN 978-1-139-47175-6.

- ^ Cormen et al. (2001), p. 844; Goodrich & Tamassia (2002), p. 279.

- ^ Cormen et al. (2001), section 28.2..

- ^ Causton, Helen; Quackenbush, John; Brazma, Alvis (2009), Microarray Gene Expression Data Analysis: A Beginner's Guide, John Wiley & Sons, pp. 49–50, ISBN 978-1-4443-1156-3.

- ^ Eidhammer, Ingvar; Barsnes, Harald; Eide, Geir Egil; Martens, Lennart (2012), Computational and Statistical Methods for Protein Quantification by Mass Spectrometry, John Wiley & Sons, p. 105, ISBN 978-1-118-49378-6.

- ^ a b Campbell, Murray; Greated, Clive (1994), The Musician's Guide to Acoustics, Oxford University Press, p. 78, ISBN 978-0-19-159167-9.

- ^ Randel, Don Michael, ed. (2003), The Harvard Dictionary of Music (4th ed.), The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, p. 416, ISBN 978-0-674-01163-2.

- ^ France, Robert (2008), Introduction to Physical Education and Sport Science, Cengage Learning, p. 282, ISBN 978-1-4180-5529-5.

- ^ Allen, Elizabeth; Triantaphillidou, Sophie (2011), The Manual of Photography, Taylor & Francis, p. 228, ISBN 978-0-240-52037-7.

- ^ a b Davis, Phil (1998), Beyond the Zone System, CRC Press, p. 17, ISBN 978-1-136-09294-7.

- ^ Allen & Triantaphillidou (2011), p. 235.

- ^ Zwerman, Susan; Okun, Jeffrey A. (2012), Visual Effects Society Handbook: Workflow and Techniques, CRC Press, p. 205, ISBN 978-1-136-13614-6.

- ^ Bauer, Craig P. (2013), Secret History: The Story of Cryptology, CRC Press, p. 332, ISBN 978-1-4665-6186-1.

- ^ Sloane, N. J. A. (ed.), "Sequence A007525 (Decimal expansion of log_2 e)", The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences, OEIS Foundation

- ^ Sloane, N. J. A. (ed.), "Sequence A020862 (Decimal expansion of log_2(10))", The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences, OEIS Foundation

- ^ a b Warren Jr., Henry S. (2002), Hacker's Delight (1st ed.), Addison Wesley, p. 215, ISBN 978-0-201-91465-8

- ^ fls, Linux kernel API, kernel.org, retrieved 2010-10-17.

- ^ Combet, M.; Van Zonneveld, H.; Verbeek, L. (December 1965), "Computation of the base two logarithm of binary numbers", IEEE Transactions on Electronic Computers, EC-14 (6): 863–867, Bibcode:1965ITECm..14..863C, doi:10.1109/pgec.1965.264080

- ^ McEniry, Charles (August 2007), The Mathematics Behind the Fast Inverse Square Root Function Code (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-11

- ^ a b c d Majithia, J. C.; Levan, D. (1973), "A note on base-2 logarithm computations", Proceedings of the IEEE, 61 (10): 1519–1520, Bibcode:1973IEEEP..61.1519M, doi:10.1109/PROC.1973.9318.

- ^ Stephenson, Ian (2005), "9.6 Fast Power, Log2, and Exp2 Functions", Production Rendering: Design and Implementation, Springer-Verlag, pp. 270–273, ISBN 978-1-84628-085-6.

- ^ Warren Jr., Henry S. (2013) [2002], "11-4: Integer Logarithm", Hacker's Delight (2nd ed.), Addison Wesley – Pearson Education, Inc., p. 291, ISBN 978-0-321-84268-8, 0-321-84268-5.

- ^ "7.12.6.10 The log2 functions", ISO/IEC 9899:1999 specification (PDF), p. 226.

- ^ Redfern, Darren; Campbell, Colin (1998), The Matlab® 5 Handbook, Springer-Verlag, p. 141, ISBN 978-1-4612-2170-8.

External links

[edit]- Weisstein, Eric W., "Binary Logarithm", MathWorld

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Anderson, Sean Eron (December 12, 2003), "Find the log base 2 of an N-bit integer in O(lg(N)) operations", Bit Twiddling Hacks, Stanford University, retrieved 2015-11-25

- Feynman and the Connection Machine

Binary logarithm

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Properties

Mathematical Definition

The binary logarithm, denoted , is defined for as the exponent to which 2 must be raised to obtain , that is, where .[6] The domain of the binary logarithm is the set of positive real numbers, with range consisting of all real numbers; it is undefined for .[7][6] As the inverse of the base-2 exponential function, the binary logarithm satisfies for all and for all real .[6] The graph of is strictly monotonic increasing on its domain, passing through the points , , and . It has a vertical asymptote at , approaching as approaches 0 from the right, and approaches as approaches .[6][7][8] Special values of the binary logarithm include , , , and .[6]Algebraic and Analytic Properties

The binary logarithm satisfies the fundamental algebraic identities shared by all logarithmic functions with base greater than 0 and not equal to 1. The product rule states that for , which follows from the exponentiation property .[9] The quotient rule provides, for , derived analogously from .[9] Additionally, the power rule holds for and real , reflecting .[9] These rules underscore the generality of binary logarithmic properties, applicable to any valid base.[9] For inequalities, the binary logarithm is strictly increasing because its base exceeds 1, yielding when and when .[9] The function is concave on , with first derivative and second derivative .[10] This concavity implies Jensen's inequality: for weights with and , with equality if all are equal.[11] The binary logarithm extends via analytic continuation to complex as , where is multi-valued due to differing by for integer ; the principal branch uses .[12] Focus here is on real positives, where it remains single-valued and analytic except at 0.[12] Its Taylor series about is converging for .[13]Relation to Other Logarithms

The binary logarithm relates to logarithms in other bases through the change of base formula, which states that for any positive base , This equivalence allows the binary logarithm to be expressed using any convenient base, facilitating its computation in various mathematical contexts.[14] In particular, when using the natural logarithm (base ), the relation simplifies to where serves as a scaling constant. Similarly, with the common logarithm (base 10), and acts as the divisor. These specific forms highlight how the binary logarithm can be derived from more fundamental logarithmic functions.[14][15] Computationally, these relations position the binary logarithm as a scaled variant of the natural or common logarithm, which is advantageous in systems where the latter are implemented as primitive operations in numerical libraries. For instance, many programming languages and hardware floating-point units compute by evaluating , leveraging efficient approximations for the natural logarithm while adjusting via the constant . This approach minimizes redundancy in algorithmic implementations, especially in binary-based computing environments.[16] A distinctive feature of the base-2 logarithm is its exactness for powers of 2, where for any integer , yielding precise integer results without approximation errors. This property ties directly to the binary numeral system, where powers of 2 correspond to simple bit shifts, and extends to dyadic rationals—rational numbers of the form with integer and nonnegative integer —which possess finite binary representations, enabling exact logarithmic evaluations in binary arithmetic contexts.[17][18]Notation

Symbolic Representations

The binary logarithm of a positive real number is most commonly denoted using the subscript notation , where the subscript explicitly indicates the base 2.[6] Alternative notations exist, though they are less prevalent; these include , which is the recommended abbreviation for the base-2 logarithm according to International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standards.[19] The symbol has been used historically in some number theoretic contexts to denote the binary logarithm, but current ISO conventions reserve for the base-10 logarithm, making a rarer variant to specify the base explicitly when needed.[6][19] In mathematical typesetting, particularly with LaTeX, the primary notation is rendered as using the command , which ensures clear subscript placement for the base.[20] This explicit base specification helps avoid ambiguity, as the unsubscripted conventionally represents the natural logarithm (base ) in much of pure mathematics or the common logarithm (base 10) in applied contexts like engineering.[21] In contrast, computer science literature often uses to implicitly mean the binary logarithm, reflecting the field's emphasis on binary representations, though explicit notation like is preferred for precision across disciplines.[21]Usage in Computing and Units

In computing, the binary logarithm is provided as a standard function in programming languages to compute for floating-point arguments. In C++, thestd::log2 function from the <cmath> header calculates the base-2 logarithm, returning a domain error for negative inputs and a pole error for zero. Similarly, Python's math.log2 function in the math module returns the base-2 logarithm of a non-negative float, raising a ValueError for negative values and returning negative infinity for zero.[22] These functions are essential for algorithms involving binary representations, such as determining the bit length of an integer, where the floor of plus one gives the number of bits required to represent in binary (for ).

The binary logarithm underpins fundamental units in information measurement. Specifically, defines the bit (binary digit) as the basic unit of information, equivalent to one choice between two equally likely outcomes.[23] For a probabilistic event with probability , the self-information is , measured in bits (or shannons, the formal unit named after Claude Shannon).[23]

Binary prefixes, approved by the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) in 1998, use powers of two to denote multiples in binary systems, avoiding confusion with decimal-based SI prefixes. For example, one kibi (Ki) equals , while one kilo equals ; similarly, one mebi (Mi) is , distinct from one mega ().[24] These prefixes, such as gibi (Gi, ) and tebi (Ti, ), are standard for expressing byte counts in computing contexts like memory and storage.[24]

In information theory, the bit serves as the unit of entropy, quantifying average uncertainty in a random variable. The entropy of a discrete distribution with probabilities is given by

in bits, where the binary logarithm ensures the measure aligns with binary encoding efficiency.[23]

In hardware, the binary logarithm facilitates normalization in IEEE 754 floating-point representation, where a number (for ) is stored as with , so .[25] This structure allows efficient extraction of the approximate binary logarithm by decoding the biased exponent and adjusting for the mantissa , critical for operations in scientific computing and graphics.[25]

History

Early Mathematical Foundations

Earlier precursors to the binary logarithm can be traced to ancient and medieval mathematics. In the 8th century, the Jain mathematician Virasena described the concept of ardhaccheda ("halving") in his work Dhavala, which counts the number of times a power of 2 can be halved, effectively computing a discrete binary logarithm. This idea was extended to bases 3 and 4, prefiguring logarithmic properties.[26] The concept of the logarithm emerged in the early 17th century as a tool to simplify complex calculations, particularly in astronomy, where multiplications and divisions of large numbers were routine. Scottish mathematician John Napier introduced the idea in his 1614 work Mirifici Logarithmorum Canonis Descriptio, defining logarithms through a kinematic model involving points moving at constant velocity and exponentially decreasing distances, approximating what would later be recognized as natural logarithms (base e). Napier's tables focused on logarithms of sines, computed over nearly a decade of effort, to aid trigonometric computations essential for celestial navigation and planetary position predictions.[27][28] Preceding Napier by about 70 years, German mathematician Michael Stifel provided an early precursor to binary logarithms in his 1544 book Arithmetica Integra. Stifel tabulated powers of 2 alongside integers, illustrating the relationship between arithmetic progressions (like 1, 2, 3, ...) and geometric progressions (like , , , ...), which implicitly captured the structure of base-2 exponentiation and its inverse. This dyadic approach highlighted the natural affinity of base 2 for calculations involving doubling and halving, though Stifel did not explicitly frame it as a logarithmic function. Independently, Swiss instrument maker Joost Bürgi developed similar logarithmic tables around 1600, published in 1620, but these also adhered to non-standard bases without emphasizing base 2.[28][29] Henry Briggs, an English mathematician, advanced the field by shifting to base-10 logarithms, publishing the first such tables in 1617 after collaborating with Napier. While Briggs' work standardized common logarithms for practical use, he explicitly computed the value of to high precision (14 decimal places) using iterative methods involving powers of 2 and square roots, underscoring base 2's foundational role in logarithmic computations. In the 1620s, these tables, including Briggs' Arithmetica Logarithmica (1624), facilitated doubling and halving operations in astronomy—such as scaling distances or intensities—by adding a constant multiple of , though binary-specific tables remained implicit rather than tabulated.[30][28] The explicit emergence of binary logarithms occurred in the 18th century, with Leonhard Euler applying them in music theory in his 1739 treatise Tentamen novae theoriae musicae. Euler used base-2 logarithms to quantify frequency ratios between musical tones, assigning an octave (a doubling of frequency) a value of 1, which provided a precise measure of tonal intervals. This marked one of the earliest documented uses of in a continuous mathematical context. By the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the general definition of as the inverse of exponentiation was formalized, first noted by John Wallis in 1685 and expanded by Johann Bernoulli in 1694, encompassing base 2 within the broader logarithmic framework. Euler further solidified this in his 1748 Introductio in analysin infinitorum, linking logarithms across bases via the change-of-base formula .[31]Adoption in Computer Science and Information Theory

The adoption of the binary logarithm in computer science and information theory began prominently in the mid-20th century, driven by the need for precise measurement of information and computational resources in binary-based systems. In 1948, Claude Shannon introduced the concept of the bit as the fundamental unit of information in his seminal paper "A Mathematical Theory of Communication," where he defined information entropy using the base-2 logarithm to quantify uncertainty in binary choices, establishing log₂ as the standard for measuring bits in communication systems.[23] This framework laid the groundwork for information theory, emphasizing binary logarithms to calculate the minimum number of bits required for encoding messages without redundancy. In the 1940s, computing pioneers like Alan Turing integrated binary representations into early machine designs, where the binary logarithm implicitly measured word lengths and computational complexity in terms of bits. Turing's involvement in projects such as the Automatic Computing Engine (ACE) at the National Physical Laboratory utilized binary arithmetic, with word sizes expressed in bits to determine storage capacity and processing efficiency, reflecting log₂ scaling for the range of representable values.[32] Similarly, John von Neumann's 1945 "First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC" advocated for pure binary over decimal systems, arguing that binary arithmetic's simplicity reduced hardware complexity and enabled logarithmic efficiency in operations like multiplication, solidifying base-2 as the dominant paradigm in electronic computers.[33] During the 1950s and 1960s, the binary logarithm gained formal prominence in algorithm analysis as computing matured. Donald Knuth's "The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 1: Fundamental Algorithms" (1968) emphasized log₂ n in asymptotic notations for evaluating time and space complexity, particularly in binary search trees and sorting algorithms, where it captured the logarithmic growth inherent to binary decisions.[34] This adoption standardized log₂ in theoretical computer science, distinguishing it from natural or common logarithms by aligning directly with binary hardware operations. By the 1980s, standardization efforts further entrenched the binary logarithm in hardware design. The IEEE 754 standard for binary floating-point arithmetic, ratified in 1985, employed biased binary exponents to represent powers of 2, implicitly relying on log₂ for scaling the significand and ensuring portable, efficient numerical computations across processors.[35] The shift from binary-coded decimal (BCD), used in earlier systems like the IBM 360 for decimal compatibility, to pure binary formats in most modern hardware—exemplified by the dominance of binary in microprocessors post-1970s—reinforced log₂ as essential for optimizing bit-level efficiency and minimizing conversion overheads.[33]Applications

Information Theory

In information theory, the binary logarithm is essential for measuring the uncertainty and information content in probabilistic systems. The Shannon entropy of a discrete random variable with probability distribution is defined as which quantifies the average number of bits needed to encode outcomes of , reflecting the expected information or surprise associated with the variable. This formulation, introduced by Claude E. Shannon in his seminal 1948 paper, establishes the binary logarithm as the natural base for information measures due to its alignment with binary decision processes in communication.[23] The bit serves as the fundamental unit of information, where bit corresponds to the resolution of a binary choice between two equiprobable events. For instance, the entropy of a fair coin flip, with , is bit, illustrating the binary logarithm's role in capturing maximal uncertainty for binary outcomes. Joint entropy extends this to multiple variables, with , where is the conditional entropy representing remaining uncertainty in given ; all terms are computed using base-2 logarithms to maintain units in bits.[23] Mutual information measures the shared information between variables and , quantifying their statistical dependence through differences in entropies, again relying on the binary logarithm for bit-scale evaluation. In communication channels, the capacity is the supremum of mutual information over input distributions, , limiting the reliable transmission rate; for the binary symmetric channel with crossover probability , , where is the binary entropy function.[23] The source coding theorem, also from Shannon's work, asserts that the binary logarithm determines the fundamental limit for data compression: no lossless code can achieve an average length below the entropy bits per symbol in the asymptotic limit, guiding practical encoding schemes like Huffman coding toward this bound. This theoretical foundation underscores the binary logarithm's centrality in establishing compression efficiency and communication limits.[23]Combinatorics and Discrete Mathematics

In combinatorics, the binary logarithm provides a natural measure for the scale of counting problems involving exponential growth. For binomial coefficients, Stirling's approximation yields a precise asymptotic estimate: for large and where , with denoting the binary entropy function (using binary logarithms). This follows from applying Stirling's formula to the factorials in , resulting in exponential bounds after simplification.[36] A fundamental application arises in subset counting, where the power set of an -element set has cardinality , as each element can independently be included or excluded, corresponding to the binary strings of length . The binary logarithm thus simplifies to , quantifying the bits required to encode any subset uniquely. This connection is central to enumerative combinatorics and bijections between sets and binary representations.[37] In discrete structures like binary trees, the binary logarithm determines minimal heights. A complete binary tree with nodes achieves the smallest possible height , since the maximum nodes up to height is , implying or . This logarithmic bound reflects the doubling of nodes per level in balanced trees.[38] Divide-and-conquer paradigms in discrete mathematics often feature binary logarithms in recurrence solutions. Consider the recurrence , modeling problems that split into two equal subproblems with linear merging cost; the Master Theorem classifies it as case 2 (, , ), yielding . The term captures the recursion depth, as each level halves the problem size over steps.[39] Exemplifying these concepts, the Tower of Hanoi requires exactly moves for disks, following the recurrence with ; thus, for large , illustrating how binary logarithms inversely scale exponential move counts to linear disk size. In the subset sum problem, deciding if a subset sums to a target involves checking possibilities in brute force, with complexity exponential in ; advanced meet-in-the-middle methods reduce it to , but the core counting bound underscores the bit-length challenge.[40][41]Computational Complexity

In computational complexity theory, the binary logarithm is fundamental to Big O notation for describing the asymptotic growth of algorithm runtime and space requirements, especially in divide-and-conquer paradigms where problems are recursively halved. It quantifies efficiency by measuring the number of steps needed to reduce a problem size from to 1 via binary decisions, leading to expressions like for balanced searches or for sorting and transforms. This notation highlights how logarithmic factors enable scalable performance for large inputs, distinguishing efficient algorithms from linear or quadratic ones.[42] A classic example is binary search on a sorted array of elements, which achieves time complexity by repeatedly dividing the search interval in half until the target is found or confirmed absent. This efficiency stems from the binary logarithm representing the height of a complete binary tree with leaves, directly corresponding to the worst-case number of comparisons. Similarly, comparison-based sorting algorithms, such as merge sort, run in time, as the process merges sorted halves across levels, each requiring work; this bound is tight due to the lower bound from information theory. The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), via the Cooley-Tukey algorithm, also operates in time for computing the discrete Fourier transform of points, by decomposing the problem into smaller subtransforms along logarithmic stages.[43][42][44] For space complexity, hash tables exemplify the role of binary logarithms in design choices that maintain constant-time operations. A hash table storing elements typically uses space overall, but sizing the table as (a power of 2) simplifies modular arithmetic in probing sequences, such as binary probing, where the expected search time remains for load factors . In open-addressing schemes, this logarithmic table sizing ensures collision resolution without degrading to linear probes, preserving amortized efficiency.[45] In complexity classes like P and NP, binary logarithms appear in reductions and analyses, such as the polynomial-time reduction from 3-SAT to vertex cover, where the constructed graph has vertices and edges for clauses, but subsequent approximation algorithms for vertex cover achieve -approximation ratios via linear programming relaxations. In parallel computing under the PRAM model, work-time tradeoffs leverage factors; for processors, algorithms like parallel sorting run in time with processors, while simulations between PRAM variants (e.g., EREW to CRCW) introduce overhead to maintain efficiency without excessive processors. These logarithmic terms underscore the tradeoffs between parallelism and sequential work in scalable systems.[46][47]Bioinformatics and Data Compression

In bioinformatics, the binary logarithm plays a key role in scoring sequence alignments, particularly in tools like BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool), where it normalizes raw scores into bit scores for comparability across databases. The bit score is calculated as , where is the raw alignment score, and are statistical parameters derived from the scoring matrix and sequence composition, and division by (the natural logarithm of 2) converts the score to a base-2 logarithmic scale. This formulation ensures that bit scores reflect information content in bits, allowing researchers to assess the significance of alignments; for instance, a bit score of 30 indicates that the alignment is as unlikely as finding a specific 30-bit sequence by chance.[48] Representing biological sequences also relies on binary logarithms to quantify storage requirements, as DNA sequences consist of four nucleotide bases (A, C, G, T), each encodable with bits. For the human genome, which comprises approximately 3.2 billion base pairs in its haploid form, this translates to about 6.4 gigabits of data in a naive binary encoding without compression. Such calculations are fundamental for genome assembly and storage in databases like GenBank, where binary logarithm-based metrics help estimate the information density of genetic data.[49] In data compression, particularly for biological sequences and general files, the binary logarithm underpins algorithms that assign code lengths proportional to symbol probabilities. Huffman coding constructs optimal prefix codes where the length of the code for a symbol with probability approximates bits, minimizing the average code length to near the source entropy while ensuring instantaneous decodability. This approach is widely used in compressing genomic data, such as FASTA files, achieving ratios close to the entropy bound; for example, in repetitive DNA regions with low entropy, compression can exceed 50% reduction in size. Similarly, Lempel-Ziv algorithms (e.g., LZ77 and LZ78) build dynamic dictionaries of patterns, encoding matches with pointers whose bit lengths scale as of the dictionary size or pattern frequency, enabling efficient compression of large datasets like protein sequences by exploiting redundancy in motif occurrences.[50][51]Music Theory and Signal Processing

In music theory, the binary logarithm plays a fundamental role in describing pitch intervals and frequency relationships, particularly within equal temperament tuning systems. An octave corresponds to a frequency ratio of 2:1, making the binary logarithm a natural measure for octave intervals, where the number of octaves between two frequencies and is given by .[52] In twelve-tone equal temperament, the octave is divided into 12 equal semitones, each with a frequency ratio of , and the interval in semitones between two frequencies is calculated as .[52] This logarithmic scaling ensures that equal steps in pitch perception align with multiplicative frequency changes, reflecting the human auditory system's sensitivity to relative rather than absolute frequency differences.[52] The Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI) standard incorporates the binary logarithm to map note numbers to frequencies, standardizing pitch representation in digital music. The frequency for MIDI note number (with A4 at 440 Hz and MIDI note 69) is Hz, derived from the equal temperament semitone interval.[52] Inversely, the MIDI note number from a frequency is , allowing precise conversion between discrete note values and continuous frequencies.[52] This formulation enables synthesizers and sequencers to generate pitches accurately across octaves, with binary octave divisions—such as halving or doubling frequencies—serving as foundational examples for tuning scales in binary or dyadic systems.[52] In signal processing, the Nyquist rate establishes the minimum sampling frequency as twice the highest signal frequency component, introducing a factor of 2 that aligns with binary logarithmic structures in digital representations.[53] This dyadic relationship facilitates subsequent decompositions, such as in wavelet transforms, where signals are analyzed at scales for integer levels , with the scale index directly related to .[54] The discrete wavelet transform decomposes the sampled signal into approximation and detail coefficients using dyadic filter banks, enabling multiresolution analysis that captures features at octave-spaced frequency bands.[55] For instance, the -th filter in a dyadic bank is scaled as , providing constant-Q filtering where bandwidths double per octave, mirroring musical frequency scaling.[55] Fourier-based methods extend this through dyadic filter banks for efficient multiresolution processing of audio signals. These banks divide the spectrum into octave bands using binary scaling, with center frequencies shifting by factors of 2, allowing localized time-frequency analysis akin to wavelet decomposition.[55] In applications like audio compression, such as MP3 encoding, psychoacoustic models employ logarithmic frequency scales to model critical bands on the Bark scale, where bandwidths approximate human perception and incorporate octave-based ratios via binary logarithms for spectral envelope representation.[56] For example, in related perceptual coders like AC-2, exponents in mantissa-exponent coding use log₂-based shifts (each multiplying amplitude by 2, or 6.02 dB), aligning quantization with dyadic psychoacoustic thresholds.[56] This integration ensures efficient bit allocation while preserving perceptual quality in digital audio.Sports Scheduling and Optimization

In single-elimination tournaments, where losers are immediately eliminated after one loss, the binary logarithm determines the number of rounds required when the number of participants is a power of two, specifically . The tournament structure forms a complete binary tree of height , with each round halving the number of remaining competitors until a single winner emerges after exactly rounds.[57] This design ensures balanced competition, as every participant has an equal path length to the final.[58] A prominent example is the NCAA Division I men's basketball tournament, known as March Madness, which features 68 teams as of 2025, including four First Four play-in games to determine the final 64 teams that enter the single-elimination bracket, requiring 6 rounds to crown a champion since . The bracket's binary tree representation highlights how each round's 32 games (in the first round) progressively reduce the field: 64 to 32, 32 to 16, 16 to 8, 8 to 4, 4 to 2, and finally 2 to 1.[59] When the number of teams is not a power of two, tournament organizers allocate byes—automatic advancements without playing—to certain participants, typically seeding higher-ranked teams, to balance the bracket by effectively padding the field to the next power of two.[58] For instance, in a 10-team single-elimination tournament, 6 byes are given in the first round to reach 16 slots (the next power of two, ), allowing the competition to proceed through 4 rounds thereafter.[60] This approach minimizes imbalances while preserving the logarithmic depth of the binary tree structure.[58] In Swiss-system tournaments, which combine elements of round-robin scheduling by pairing players of similar standings in each round without elimination, the binary logarithm guides the minimum number of rounds needed to reliably rank participants and resolve ties. Approximately rounds suffice to distinguish top performers from the field of entrants, as each round effectively halves the uncertainty in relative strengths, similar to a binary search process.[61] This format is widely used in chess and other individual sports to handle large fields efficiently, enabling parallel matches across multiple boards while approximating a full round-robin outcome in far fewer total games.[61] Binary logarithms also appear in optimization algorithms for sports scheduling and analytics, particularly through binary search methods that achieve time complexity for parameter tuning in resource allocation problems. In constructing home-away patterns for league schedules, binary search iteratively tests feasible widths or constraints to minimize breaks or conflicts, ensuring balanced timetables across teams.[62] For example, in the traveling tournament problem—optimizing road trips and game sequences—binary search integrates with constraint solvers to efficiently explore solution spaces for venue and timing allocations.[63] In fantasy sports analytics, binary search leverages efficiency to rank and select players from large databases, aiding resource allocation in lineup optimization. For instance, searching sorted projections of thousands of athletes to identify optimal combinations under salary caps mirrors binary search's divide-and-conquer approach, reducing evaluation time from linear to logarithmic scales.[64] This is evident in mixed-integer programming models for fantasy contests, where binary search refines player rankings and trade evaluations to maximize projected points.[64]Photography and Image Processing

In photography, the binary logarithm plays a fundamental role in quantifying exposure through the exposure value (EV), which combines aperture, shutter speed, and ISO sensitivity into a single metric representing the light intensity reaching the sensor. The EV is defined as EV = log₂(N² / t) + log₂(ISO/100), where N is the f-number (aperture), t is the exposure time in seconds, and ISO is the sensitivity setting normalized to ISO 100 as the reference.[65] This formulation arises because each unit increase in EV corresponds to a doubling of the exposure, aligning with the binary nature of light doubling in photographic stops. For instance, f-stops are spaced at intervals that approximate binary logarithmic progression, where each full stop (e.g., from f/2.8 to f/4) halves the light intake, equivalent to a change of -1 in log₂ terms.[66] Dynamic range in image sensors, often expressed in "stops," directly utilizes the binary logarithm to measure the sensor's latitude, or the ratio of the maximum to minimum detectable signal levels before noise dominates. It is calculated as log₂(max/min), where max and min represent the highest and lowest luminance values the sensor can faithfully reproduce, yielding the number of stops of latitude.[67] For example, a sensor with 14 stops of dynamic range can capture scene details across a brightness ratio of 2¹⁴ (16,384:1), crucial for high-contrast scenes like landscapes with bright skies and shadowed foregrounds. This logarithmic scale ensures that additive changes in stops correspond to multiplicative changes in light intensity, mirroring the perceptual response of the human eye to brightness.[68] Digital image bit depth, which determines the number of discrete intensity levels per channel, is inherently tied to the binary logarithm, as the total levels equal 2 raised to the power of the bit depth. An 8-bit image per channel provides 256 levels (2⁸), sufficient for standard displays but prone to banding in gradients, while RAW files typically use 12- to 16-bit depths (4,096 to 65,536 levels) to preserve more tonal information from the sensor.[69] In gamma correction, which adjusts for the non-linear response of displays and sensors, the binary logarithm underpins the encoding by mapping linear light values to a logarithmic perceptual scale, often approximated in bit-limited systems to optimize contrast without exceeding the available dynamic range.[70] Histogram equalization enhances image contrast by redistributing pixel intensities to achieve a more uniform histogram, with the underlying rationale rooted in maximizing information entropy, calculated using the binary logarithm as H = -∑ p_i log₂(p_i), where p_i is the probability of intensity i. This entropy maximization ensures even utilization of the available bit depth, improving visibility in low-contrast regions without introducing artifacts.[71] For a typical 8-bit grayscale image, equalization spreads the 256 levels to better approximate uniform distribution, leveraging log₂ to quantify and balance the information content across the dynamic range.Calculation Methods

Conversion from Other Logarithmic Bases

The binary logarithm of a positive real number , denoted , can be computed from the logarithm in any other base using the change-of-base formula .[72] This approach is practical in computational settings where values of are precomputed and stored as constants to avoid repeated calculations, as remains fixed for a given base.[15] The method leverages the availability of logarithm functions in other bases within software libraries or hardware. A common implementation uses the natural logarithm (base ), where , with pre-stored for efficiency.[15] Similarly, the common logarithm (base 10) can be used via , where is the precomputed constant.[73] In floating-point arithmetic, these ratio computations introduce potential precision errors due to rounding in both the numerator and denominator, as well as in the division operation itself.[74] For instance, when using base 10, the irrationality of can lead to accumulated rounding errors exceeding 1 unit in the last place (ULP) in some implementations, particularly for values of near powers of 10.[74] Catastrophic cancellation is less common here than in direct subtractions, but the overall relative error remains bounded by the precision of the underlying logarithm function, typically within a few ULPs on compliant IEEE 754 systems.[35] As an example, consider computing : using the natural logarithm method, , so exactly, assuming ideal arithmetic; in floating-point, the result aligns precisely due to the multiplicative relationship.[15]Rounding to Nearest Integer

The floor of the binary logarithm of a positive integer , denoted , plus one yields the minimum number of bits required to represent in binary notation.[75] This follows from the property that for in the interval , lies in , so the binary representation spans bits.[75] Rounding to the nearest integer provides the exponent of the power of 2 closest to , which is useful for identifying approximate scales in binary systems.[76] To determine the nearest power, compute the fractional part of : if it is less than 0.5, round down to ; otherwise, round up to .[76] Common methods for these computations include evaluating via floating-point libraries and applying floor or round operations, which offer high precision for most practical .[77] In integer-only contexts, bit manipulation techniques are preferred for efficiency; for instance, in GCC, the__builtin_clz(n) intrinsic counts leading zeros in the 32-bit representation of , yielding . For 64-bit integers, the equivalent is .

For example, , so bits are needed for its binary form (1010), and rounding to the nearest integer gives 3, corresponding to the closest power .[6] In memory allocation schemes like the buddy system, allocation requests are rounded up to the next power of 2—often via ceiling the binary logarithm—to enable simple splitting and coalescing of fixed-size blocks.[78]

Piecewise Linear Approximations

Piecewise linear approximations provide an efficient method for computing binary logarithms in hardware-constrained environments by dividing the normalization interval [1, 2) into multiple subintervals and applying linear interpolation within each. For a normalized input where and is the integer exponent, the binary logarithm is , so the focus is on approximating over [1, 2). The interval is segmented into equal or optimized parts, with precomputed values of at the boundaries stored in a lookup table (LUT); within each segment , the approximation uses linear interpolation: This approach leverages the smoothness of the logarithm function to achieve low computational overhead using additions and shifts.[79] A common table-based variant targets the fractional part of the mantissa, approximating where and . Here, a small LUT stores segment endpoints and interpolation coefficients derived from , often using the leading bits of to index the table. For instance, with 8 bits of the mantissa as input, a 256-entry LUT can provide coefficients for linear interpolation, enabling high throughput in parallel architectures. This method reduces table size compared to full function tables while maintaining accuracy suitable for fixed-point computations.[79] To minimize approximation error, segment boundaries are chosen using techniques like uniform spacing or Chebyshev-optimal placement, which equioscillates the error to bound the maximum deviation below a target . Uniform spacing offers simplicity but uneven error distribution, whereas Chebyshev spacing ensures the maximum absolute error is equal across segments, achieving near-minimax optimality; for example, dividing [1, 2) into 8 segments with Chebyshev nodes can limit the maximum error to under (about 0.1% relative error). Such optimizations are critical for applications requiring consistent precision without post-correction. In graphics processing units (GPUs), piecewise linear approximations are implemented for mantissa processing to accelerate logarithmic operations in shaders and physics simulations. A typical design uses 4 segments over [1, 2), with non-uniform partitioning to flatten error distribution—e.g., denser segments near 1 where the function is steeper—combined with a small LUT (e.g., 16-32 entries) for boundary values and slopes. This yields a maximum relative error of around 0.5% while using only shifts, additions, and table lookups, integrated into SIMD pipelines for low-latency evaluation.[80] These approximations excel in hardware due to their speed and minimal resource use, offering latencies under 5 cycles versus 10-20 for iterative methods, with area costs as low as 36 LUTs on FPGAs for 10-bit accuracy. They are particularly advantageous in power-sensitive devices like embedded GPUs, where trading minor precision for throughput enables real-time computations in signal processing and graphics.[79]Iterative Numerical Methods

Iterative numerical methods provide efficient ways to compute the binary logarithm to high precision by solving the root-finding problem for and . These algorithms iteratively refine an initial guess, leveraging the inverse relationship between exponentiation and logarithms, and are particularly useful when table-based approximations are insufficient for extended precision.[81] The Newton-Raphson method applies the standard root-finding iteration to this equation. Starting from an initial approximation , the update is given by where . Substituting yields with . This formulation ensures rapid refinement, assuming the initial guess is reasonably close to the root.[82] The bisection method, or binary search, operates by repeatedly halving an initial interval containing the root, where . At each step, compute the midpoint ; if , set ; otherwise, set . Continue until the interval width satisfies the desired precision, such as . This approach guarantees convergence without requiring derivatives.[83] The arithmetic-geometric mean (AGM) iteration can be adapted to compute by first scaling to a convenient form and using the relation , where is precomputed via AGM. The AGM computes using relations to elliptic integrals with appropriate initial values, iterating the arithmetic and geometric means until convergence.[84] For general , preliminary steps reduce it to a form amenable to AGM, often involving a few exponentiations. Newton-Raphson exhibits quadratic convergence, roughly doubling the number of correct digits per iteration near the root, while bisection achieves linear convergence, halving the error interval each step. AGM converges cubically or faster in practice for logarithm computation, depending on the implementation.[82][83][84] A common initial guess for these methods leverages the floating-point representation of , taking the unbiased exponent as and adjusting for the mantissa in . For double-precision accuracy (about 53 binary digits), Newton-Raphson typically requires 5-10 iterations from such a starting point, while bisection needs around 60 steps, and AGM converges in iterations.[82][83]Software and Hardware Support

The C standard library, via the<math.h> header, provides the log2(double x) function to compute the base-2 logarithm of a non-negative real number x, along with log2f(float x) and log2l(long double x) variants for single and extended precision, respectively.[85] These functions follow IEEE 754 semantics and are available in implementations like glibc and Microsoft's C runtime.[86]

In Python, the math module includes math.log2(x), which returns the base-2 logarithm of x and is optimized for efficiency over math.log(x, 2).[22] This function supports floating-point inputs and adheres to IEEE 754 behavior for special values.

Java's java.lang.Math class offers Math.log2(double a) since Java SE 9, directly computing the base-2 logarithm; prior versions use Math.log(a) / Math.log(2) as an equivalent.

On x86 architectures, hardware support for binary logarithms is provided by the x87 FPU's FYL2X instruction, which computes y * log₂(x) (set y = 1 for pure log₂), offering precise results to floating-point precision across scalar and vector modes in SSE/AVX extensions. Modern implementations may use approximate methods in AVX-512 for vectorized operations, balancing speed and accuracy. For ARM architectures, the NEON SIMD extension and VFP unit support floating-point operations, with binary logarithms computed via library calls implementing natural logarithms divided by , as no direct hardware instructions for logarithms exist in standard NEON.

NVIDIA GPUs via CUDA provide __log2f(float x) for single-precision base-2 logarithm and __log2(double x) for double-precision, with fast approximate variants like __nv_fast_log2f for performance-critical code; these support single and double precision modes and are optimized for parallel execution on SM units.

Binary logarithm functions handle edge cases per IEEE 754: log₂(±0) returns -∞, log₂(negative) or log₂(NaN) returns NaN, and log₂(+∞) returns +∞, with underflow to -∞ for subnormal inputs near zero and no overflow for finite positive x.[85]

On modern x86 CPUs like Intel Alder Lake, the log2 function typically exhibits a latency of 10-20 cycles and throughput of 4-8 operations per cycle, depending on precision and vectorization, enabling efficient use in loops.[87]