Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Perfect number

View on Wikipedia

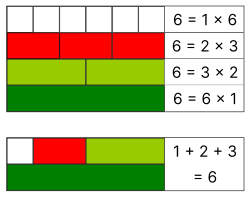

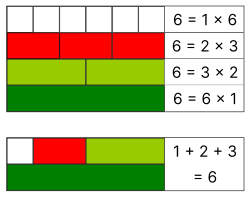

In number theory, a perfect number is a positive integer that is equal to the sum of its positive proper divisors, that is, divisors excluding the number itself.[1] For instance, 6 has proper divisors 1, 2, and 3, and 1 + 2 + 3 = 6, so 6 is a perfect number. The next perfect number is 28, because 1 + 2 + 4 + 7 + 14 = 28.

The first seven perfect numbers are 6, 28, 496, 8128, 33550336, 8589869056, and 137438691328.[2]

The sum of proper divisors of a number is called its aliquot sum, so a perfect number is one that is equal to its aliquot sum. Equivalently, a perfect number is a number that is half the sum of all of its positive divisors; in symbols, where is the sum-of-divisors function.

This definition is ancient, appearing as early as Euclid's Elements (VII.22) where it is called τέλειος ἀριθμός (perfect, ideal, or complete number). Euclid also proved a formation rule (IX.36) whereby is an even perfect number whenever is a prime of the form for positive integer —what is now called a Mersenne prime. Two millennia later, Leonhard Euler proved that all even perfect numbers are of this form.[3] This is known as the Euclid–Euler theorem.

It is not known whether there are any odd perfect numbers, nor whether infinitely many perfect numbers exist.

History

[edit]In about 300 BC Euclid showed that if 2p − 1 is prime then 2p−1(2p − 1) is perfect. The first four perfect numbers were the only ones known to early Greek mathematics, and the mathematician Nicomachus noted 8128 as early as around AD 100.[4] In modern language, Nicomachus states without proof that every perfect number is of the form where is prime.[5][6] He seems to be unaware that n itself has to be prime. He also says (wrongly) that the perfect numbers end in 6 or 8 alternately. (The first 5 perfect numbers end with digits 6, 8, 6, 8, 6; but the sixth also ends in 6.) Philo of Alexandria in his first-century book "On the creation" mentions perfect numbers, claiming that the world was created in 6 days and the moon orbits in 28 days because 6 and 28 are perfect. Philo is followed by Origen,[7] and by Didymus the Blind, who adds the observation that there are only four perfect numbers that are less than 10,000. (Commentary on Genesis 1. 14–19).[8] Augustine of Hippo defines perfect numbers in The City of God (Book XI, Chapter 30) in the early 5th century AD, repeating the claim that God created the world in 6 days because 6 is the smallest perfect number. The Egyptian mathematician Ismail ibn Fallūs (1194–1252) mentioned the next three perfect numbers (33,550,336; 8,589,869,056; and 137,438,691,328) and listed a few more which are now known to be incorrect.[9] The first known European mention of the fifth perfect number is a manuscript written between 1456 and 1461 by an unknown mathematician.[10] In 1588, the Italian mathematician Pietro Cataldi identified the sixth (8,589,869,056) and the seventh (137,438,691,328) perfect numbers, and also proved that every perfect number obtained from Euclid's rule ends with a 6 or an 8.[11][12][13]

Even perfect numbers

[edit]Euclid proved that is an even perfect number whenever is prime (Elements, Prop. IX.36).

For example, the first four perfect numbers are generated by the formula with p a prime number, as follows:

Prime numbers of the form are known as Mersenne primes, after the seventeenth-century monk Marin Mersenne, who studied number theory and perfect numbers. For to be prime, it is necessary that p itself be prime. However, not all numbers of the form with a prime p are prime; for example, 211 − 1 = 2047 = 23 × 89 is not a prime number.[a] In fact, Mersenne primes are very rare: of the approximately 4 million primes p up to 68,874,199, is prime for only 48 of them.[14]

While Nicomachus had stated (without proof) that all perfect numbers were of the form where is prime (though he stated this somewhat differently), Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) circa AD 1000 was unwilling to go that far, declaring instead (also without proof) that the formula yielded only every even perfect number.[15] It was not until the 18th century that Leonhard Euler proved that the formula indeed yields all the even perfect numbers. Thus, there is a one-to-one correspondence between even perfect numbers and Mersenne primes; each Mersenne prime generates one even perfect number, and vice versa. This result is often referred to as the Euclid–Euler theorem.

An exhaustive search by the GIMPS distributed computing project has shown that the first 50 even perfect numbers are for

- p = 2, 3, 5, 7, 13, 17, 19, 31, 61, 89, 107, 127, 521, 607, 1279, 2203, 2281, 3217, 4253, 4423, 9689, 9941, 11213, 19937, 21701, 23209, 44497, 86243, 110503, 132049, 216091, 756839, 859433, 1257787, 1398269, 2976221, 3021377, 6972593, 13466917, 20996011, 24036583, 25964951, 30402457, 32582657, 37156667, 42643801, 43112609, 57885161, 74207281, 77232917 OEIS: A000043.[14]

Two higher perfect numbers have also been discovered, namely those for which p = 82589933 and 136279841. Although it is still possible there may be others within this range, initial but exhaustive tests by GIMPS have revealed no other perfect numbers for p below 138277717. As of October 2024[update], 52 Mersenne primes are known,[16] and therefore 52 even perfect numbers (the largest of which is 2136279840 × (2136279841 − 1) with 82,048,640 digits). It is not known whether there are infinitely many perfect numbers, nor whether there are infinitely many Mersenne primes.

As well as having the form , each even perfect number is the -th triangular number (and hence equal to the sum of the integers from 1 to ) and the -th hexagonal number. Furthermore, each even perfect number except for 6 is the -th centered nonagonal number and is equal to the sum of the first odd cubes (odd cubes up to the cube of ):

Even perfect numbers (except 6) are of the form

with each resulting triangular number T7 = 28, T31 = 496, T127 = 8128 (after subtracting 1 from the perfect number and dividing the result by 9) ending in 3 or 5, the sequence starting with T2 = 3, T10 = 55, T42 = 903, T2730 = 3727815, ...[17] It follows that by adding the digits of any even perfect number (except 6), then adding the digits of the resulting number, and repeating this process until a single digit (called the digital root) is obtained, always produces the number 1. For example, the digital root of 8128 is 1, because 8 + 1 + 2 + 8 = 19, 1 + 9 = 10, and 1 + 0 = 1. This works with all perfect numbers with odd prime p and, in fact, with all numbers of the form for odd integer (not necessarily prime) m.

Owing to their form, every even perfect number is represented in binary form as p ones followed by p − 1 zeros; for example:

Thus every even perfect number is a pernicious number.

Every even perfect number is also a practical number (cf. Related concepts).

Odd perfect numbers

[edit]It is unknown whether any odd perfect numbers exist, though various results have been obtained. In 1496, Jacques Lefèvre stated that Euclid's rule gives all perfect numbers,[18] thus implying that no odd perfect number exists, but Euler himself stated: "Whether ... there are any odd perfect numbers is a most difficult question".[19] More recently, Carl Pomerance has presented a heuristic argument suggesting that indeed no odd perfect number should exist.[20] All perfect numbers are also harmonic divisor numbers, and it has been conjectured as well that there are no odd harmonic divisor numbers other than 1.

Any odd perfect number N must satisfy the following conditions:

- N > 101500.[21]

- N is not divisible by 105.[22]

- N is of the form N ≡ 1 (mod 12) or N ≡ 117 (mod 468) or N ≡ 81 (mod 324).[23]

- The largest prime power pa that divides N is greater than 1062.[21]

- The largest prime factor of N is greater than 108,[24] and less than [25]

- The second largest prime factor is greater than 104,[26] and is less than .[27]

- The third largest prime factor is greater than 100,[28] and less than [29]

- N has at least 101 prime factors and at least 10 distinct prime factors.[21][30] If 3 does not divide N, then N has at least 12 distinct prime factors.[31]

- N is of the form

- where:

Furthermore, several minor results are known about the exponents e1, ..., ek.

- Not all ei ≡ 1 (mod 3).[40]

- Not all ei ≡ 2 (mod 5).[41]

- If all ei ≡ 1 (mod 3) or 2 (mod 5), then the smallest prime factor of N must lie between 108 and 101000.[41]

- More generally, if all 2ei+1 have a prime factor in a given finite set S, then the smallest prime factor of N must be smaller than an effectively computable constant depending only on S.[41]

- If (e1, ..., ek) = (1, ..., 1, 2, ..., 2) with t ones and u twos, then .[42]

- (e1, ..., ek) ≠ (1, ..., 1, 3),[43] (1, ..., 1, 5), (1, ..., 1, 6).[44]

- If e1 = ... = ek = e, then

In 1888, Sylvester stated:[48]

... a prolonged meditation on the subject has satisfied me that the existence of any one such [odd perfect number]—its escape, so to say, from the complex web of conditions which hem it in on all sides—would be little short of a miracle.

On the other hand, several odd integers come close to being perfect. René Descartes observed that the number D = 32 ⋅ 72 ⋅ 112 ⋅ 132 ⋅ 22021 = (3⋅1001)2 ⋅ (22⋅1001 − 1) = 198585576189 would be an odd perfect number if only 22021 (= 192 ⋅ 61) were a prime number. The odd numbers with this property (they would be perfect if one of their composite factors were prime) are the Descartes numbers. Many of the properties proven about odd perfect numbers also apply to Descartes numbers, and Pace Nielsen has suggested that sufficient study of these numbers may lead to a proof that no odd perfect numbers exist.[49]

Minor results

[edit]All even perfect numbers have a very precise form; odd perfect numbers either do not exist or are rare. There are a number of results on perfect numbers that are actually quite easy to prove but nevertheless superficially impressive; some of them also come under Richard Guy's strong law of small numbers:

- The only even perfect number of the form n3 + 1 is 28 (Makowski 1962).[50]

- 28 is also the only even perfect number that is a sum of two positive cubes of integers (Gallardo 2010).[51]

- The reciprocals of the divisors of a perfect number N must add up to 2 (to get this, take the definition of a perfect number, , and divide both sides by n):

- For 6, we have ;

- For 28, we have , etc.

- The number of divisors of a perfect number (whether even or odd) must be even, because N cannot be a perfect square.[52]

- From these two results it follows that every perfect number is an Ore's harmonic number.

- The even perfect numbers are not trapezoidal numbers; that is, they cannot be represented as the difference of two positive non-consecutive triangular numbers. There are only three types of non-trapezoidal numbers: even perfect numbers, powers of two, and the numbers of the form formed as the product of a Fermat prime with a power of two in a similar way to the construction of even perfect numbers from Mersenne primes.[53]

- The number of perfect numbers less than n is less than , where c > 0 is a constant.[54] In fact it is , using little-o notation.[55]

- Every even perfect number ends in 6 or 28 in base ten and, with the only exception of 6, ends in 1 in base 9.[56][57] Therefore, in particular the digital root of every even perfect number other than 6 is 1.

- The only square-free perfect number is 6.[58]

Related concepts

[edit]

The sum of proper divisors gives various other kinds of numbers. Numbers where the sum is less than the number itself are called deficient, and where it is greater than the number, abundant. These terms, together with perfect itself, come from Greek numerology. A pair of numbers which are the sum of each other's proper divisors are called amicable, and larger cycles of numbers are called sociable. A positive integer such that every smaller positive integer is a sum of distinct divisors of it is a practical number.

By definition, a perfect number is a fixed point of the restricted divisor function s(n) = σ(n) − n, and the aliquot sequence associated with a perfect number is a constant sequence. All perfect numbers are also -perfect numbers, or Granville numbers.

A semiperfect number is a natural number that is equal to the sum of all or some of its proper divisors. A semiperfect number that is equal to the sum of all its proper divisors is a perfect number. Most abundant numbers are also semiperfect; abundant numbers which are not semiperfect are called weird numbers.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ All factors of are congruent to 1 mod 2p. For example, 211 − 1 = 2047 = 23 × 89, and both 23 and 89 yield a remainder of 1 when divided by 22. Furthermore, whenever p is a Sophie Germain prime—that is, 2p + 1 is also prime—and 2p + 1 is congruent to 1 or 7 mod 8, then 2p + 1 will be a factor of which is the case for p = 11, 23, 83, 131, 179, 191, 239, 251, ... OEIS: A002515.

References

[edit]- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Perfect Number". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2025-02-09.

Perfect numbers are positive integers n such that n=s(n), where s(n) is the restricted divisor function (i.e., the sum of proper divisors of n), ...

- ^ "A000396 - OEIS". oeis.org. Retrieved 2024-03-21.

- ^ Caldwell, Chris, "A proof that all even perfect numbers are a power of two times a Mersenne prime".

- ^ Dickson, L. E. (1919). History of the Theory of Numbers, Vol. I. Washington: Carnegie Institution of Washington. p. 4.

- ^ "Perfect numbers". www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ In Introduction to Arithmetic, Chapter 16, he says of perfect numbers, "There is a method of producing them, neat and unfailing, which neither passes by any of the perfect numbers nor fails to differentiate any of those that are not such, which is carried out in the following way." He then goes on to explain a procedure which is equivalent to finding a triangular number based on a Mersenne prime.

- ^ Commentary on the Gospel of John 28.1.1–4, with further references in the Sources Chrétiennes edition: vol. 385, 58–61.

- ^ Rogers, Justin M. (2015). The Reception of Philonic Arithmological Exegesis in Didymus the Blind's Commentary on Genesis (PDF). Society of Biblical Literature National Meeting, Atlanta, Georgia.

- ^ Roshdi Rashed, The Development of Arabic Mathematics: Between Arithmetic and Algebra (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1994), pp. 328–329.

- ^ Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 14908. See David Eugene Smith (1925). History of Mathematics: Volume II. New York: Dover. p. 21. ISBN 0-486-20430-8.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Dickson, L. E. (1919). History of the Theory of Numbers, Vol. I. Washington: Carnegie Institution of Washington. p. 10.

- ^ Pickover, C (2001). Wonders of Numbers: Adventures in Mathematics, Mind, and Meaning. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 360. ISBN 0-19-515799-0.

- ^ Peterson, I (2002). Mathematical Treks: From Surreal Numbers to Magic Circles. Washington: Mathematical Association of America. p. 132. ISBN 88-8358-537-2.

- ^ a b "GIMPS Milestones Report". Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Abu Ali al-Hasan ibn al-Haytham", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ "GIMPS Home". Mersenne.org. Retrieved 2024-10-21.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Perfect Number". MathWorld.

- ^ Dickson, L. E. (1919). History of the Theory of Numbers, Vol. I. Washington: Carnegie Institution of Washington. p. 6.

- ^ "The oldest open problem in mathematics" (PDF). Harvard.edu. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- ^ Oddperfect.org. Archived 2006-12-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Ochem, Pascal; Rao, Michaël (2012). "Odd perfect numbers are greater than 101500" (PDF). Mathematics of Computation. 81 (279): 1869–1877. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-2012-02563-4. ISSN 0025-5718. Zbl 1263.11005.

- ^ Kühnel, Ullrich (1950). "Verschärfung der notwendigen Bedingungen für die Existenz von ungeraden vollkommenen Zahlen". Mathematische Zeitschrift (in German). 52: 202–211. doi:10.1007/BF02230691. S2CID 120754476.

- ^ Roberts, T (2008). "On the Form of an Odd Perfect Number" (PDF). Australian Mathematical Gazette. 35 (4): 244.

- ^ Goto, T; Ohno, Y (2008). "Odd perfect numbers have a prime factor exceeding 108" (PDF). Mathematics of Computation. 77 (263): 1859–1868. Bibcode:2008MaCom..77.1859G. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-08-02050-9. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ Konyagin, Sergei; Acquaah, Peter (2012). "On Prime Factors of Odd Perfect Numbers". International Journal of Number Theory. 8 (6): 1537–1540. doi:10.1142/S1793042112500935.

- ^ Iannucci, DE (1999). "The second largest prime divisor of an odd perfect number exceeds ten thousand" (PDF). Mathematics of Computation. 68 (228): 1749–1760. Bibcode:1999MaCom..68.1749I. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-99-01126-6. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ Zelinsky, Joshua (July 2019). "Upper bounds on the second largest prime factor of an odd perfect number". International Journal of Number Theory. 15 (6): 1183–1189. arXiv:1810.11734. doi:10.1142/S1793042119500659. S2CID 62885986..

- ^ Iannucci, DE (2000). "The third largest prime divisor of an odd perfect number exceeds one hundred" (PDF). Mathematics of Computation. 69 (230): 867–879. Bibcode:2000MaCom..69..867I. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-99-01127-8. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ Bibby, Sean; Vyncke, Pieter; Zelinsky, Joshua (23 November 2021). "On the Third Largest Prime Divisor of an Odd Perfect Number" (PDF). Integers. 21. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ Nielsen, Pace P. (2015). "Odd perfect numbers, Diophantine equations, and upper bounds" (PDF). Mathematics of Computation. 84 (295): 2549–2567. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-2015-02941-X. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ Nielsen, Pace P. (2007). "Odd perfect numbers have at least nine distinct prime factors" (PDF). Mathematics of Computation. 76 (260): 2109–2126. arXiv:math/0602485. Bibcode:2007MaCom..76.2109N. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-07-01990-4. S2CID 2767519. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ a b Zelinsky, Joshua (3 August 2021). "On the Total Number of Prime Factors of an Odd Perfect Number" (PDF). Integers. 21. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Chen, Yong-Gao; Tang, Cui-E (2014). "Improved upper bounds for odd multiperfect numbers". Bulletin of the Australian Mathematical Society. 89 (3): 353–359. doi:10.1017/S0004972713000488.

- ^ Nielsen, Pace P. (2003). "An upper bound for odd perfect numbers". Integers. 3. doi:10.5281/zenodo.7607545. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ Ochem, Pascal; Rao, Michaël (2014). "On the number of prime factors of an odd perfect number". Mathematics of Computation. 83 (289): 2435–2439. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-2013-02776-7.

- ^ Graeme Clayton, Cody Hansen (2023). "On inequalities involving counts of the prime factors of an odd perfect number" (PDF). Integers. 23. arXiv:2303.11974. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ^ Pomerance, Carl; Luca, Florian (2010). "On the radical of a perfect number". New York Journal of Mathematics. 16: 23–30. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ Cohen, Graeme (1978). "On odd perfect numbers". Fibonacci Quarterly. 16 (6): 523-527. doi:10.1080/00150517.1978.12430277.

- ^ Suryanarayana, D. (1963). "On Odd Perfect Numbers II". Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society. 14 (6): 896–904. doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-1963-0155786-8.

- ^ McDaniel, Wayne L. (1970). "The non-existence of odd perfect numbers of a certain form". Archiv der Mathematik. 21 (1): 52–53. doi:10.1007/BF01220877. ISSN 1420-8938. MR 0258723. S2CID 121251041.

- ^ a b c Fletcher, S. Adam; Nielsen, Pace P.; Ochem, Pascal (2012). "Sieve methods for odd perfect numbers" (PDF). Mathematics of Computation. 81 (279): 1753?1776. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-2011-02576-7. ISSN 0025-5718. MR 2904601.

- ^ Cohen, G. L. (1987). "On the largest component of an odd perfect number". Journal of the Australian Mathematical Society, Series A. 42 (2): 280–286. doi:10.1017/S1446788700028251. ISSN 1446-8107. MR 0869751.

- ^ Kanold, Hans-Joachim [in German] (1950). "Satze uber Kreisteilungspolynome und ihre Anwendungen auf einige zahlentheoretisehe Probleme. II". Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik. 188 (1): 129–146. doi:10.1515/crll.1950.188.129. ISSN 1435-5345. MR 0044579. S2CID 122452828.

- ^ a b Cohen, G. L.; Williams, R. J. (1985). "Extensions of some results concerning odd perfect numbers" (PDF). Fibonacci Quarterly. 23 (1): 70–76. doi:10.1080/00150517.1985.12429857. ISSN 0015-0517. MR 0786364.

- ^ Hagis, Peter Jr.; McDaniel, Wayne L. (1972). "A new result concerning the structure of odd perfect numbers". Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society. 32 (1): 13–15. doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-1972-0292740-5. ISSN 1088-6826. MR 0292740.

- ^ McDaniel, Wayne L.; Hagis, Peter Jr. (1975). "Some results concerning the non-existence of odd perfect numbers of the form " (PDF). Fibonacci Quarterly. 13 (1): 25–28. doi:10.1080/00150517.1975.12430680. ISSN 0015-0517. MR 0354538.

- ^ Yamada, Tomohiro (2019). "A new upper bound for odd perfect numbers of a special form". Colloquium Mathematicum. 156 (1): 15–21. arXiv:1706.09341. doi:10.4064/cm7339-3-2018. ISSN 1730-6302. S2CID 119175632.

- ^ The Collected Mathematical Papers of James Joseph Sylvester p. 590, tr. from "Sur les nombres dits de Hamilton", Compte Rendu de l'Association Française (Toulouse, 1887), pp. 164–168.

- ^ Nadis, Steve (10 September 2020). "Mathematicians Open a New Front on an Ancient Number Problem". Quanta Magazine. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ Makowski, A. (1962). "Remark on perfect numbers". Elem. Math. 17 (5): 109.

- ^ Gallardo, Luis H. (2010). "On a remark of Makowski about perfect numbers". Elem. Math. 65 (3): 121–126. doi:10.4171/EM/149..

- ^ Yan, Song Y. (2012), Computational Number Theory and Modern Cryptography, John Wiley & Sons, Section 2.3, Exercise 2(6), ISBN 9781118188613.

- ^ Jones, Chris; Lord, Nick (1999). "Characterising non-trapezoidal numbers". The Mathematical Gazette. 83 (497). The Mathematical Association: 262–263. doi:10.2307/3619053. JSTOR 3619053. S2CID 125545112.

- ^ Hornfeck, B (1955). "Zur Dichte der Menge der vollkommenen zahlen". Arch. Math. 6 (6): 442–443. doi:10.1007/BF01901120. S2CID 122525522.

- ^ Kanold, HJ (1956). "Eine Bemerkung ¨uber die Menge der vollkommenen zahlen". Math. Ann. 131 (4): 390–392. doi:10.1007/BF01350108. S2CID 122353640.

- ^ H. Novarese. Note sur les nombres parfaits Texeira J. VIII (1886), 11–16.

- ^ Dickson, L. E. (1919). History of the Theory of Numbers, Vol. I. Washington: Carnegie Institution of Washington. p. 25.

- ^ Redmond, Don (1996). Number Theory: An Introduction to Pure and Applied Mathematics. Chapman & Hall/CRC Pure and Applied Mathematics. Vol. 201. CRC Press. Problem 7.4.11, p. 428. ISBN 9780824796969..

Sources

[edit]- Euclid, Elements, Book IX, Proposition 36. See D.E. Joyce's website for a translation and discussion of this proposition and its proof.

- Kanold, H.-J. (1941). "Untersuchungen über ungerade vollkommene Zahlen". Journal für die Reine und Angewandte Mathematik. 1941 (183): 98–109. doi:10.1515/crll.1941.183.98. S2CID 115983363.

- Steuerwald, R. "Verschärfung einer notwendigen Bedingung für die Existenz einer ungeraden vollkommenen Zahl". S.-B. Bayer. Akad. Wiss. 1937: 69–72.

- Tóth, László (2025). "Odd Spoof Multiperfect Numbers" (PDF). Integers. 25 (A19). arXiv:2502.16954.

Further reading

[edit]- Nankar, M.L.: "History of perfect numbers", Ganita Bharati 1, no. 1–2 (1979), 7–8.

- Hagis, P. (1973). "A Lower Bound for the set of odd Perfect Prime Numbers". Mathematics of Computation. 27 (124): 951–953. doi:10.2307/2005530. JSTOR 2005530.

- Riele, H.J.J. "Perfect Numbers and Aliquot Sequences" in H.W. Lenstra and R. Tijdeman (eds.): Computational Methods in Number Theory, Vol. 154, Amsterdam, 1982, pp. 141–157.

- Riesel, H. Prime Numbers and Computer Methods for Factorisation, Birkhauser, 1985.

- Sándor, Jozsef; Crstici, Borislav (2004). Handbook of number theory II. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic. pp. 15–98. ISBN 1-4020-2546-7. Zbl 1079.11001.

External links

[edit]- "Perfect number", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- David Moews: Perfect, amicable, and sociable numbers

- Perfect numbers – History and Theory

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Perfect Number". MathWorld.

- OEIS sequence A000396 (Perfect numbers)

- Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search (GIMPS)

- Perfect Numbers, math forum at Drexel

- Grimes, James. "8128: Perfect Numbers". Numberphile. Brady Haran. Archived from the original on 2013-05-31. Retrieved 2013-04-02.

![{\displaystyle {\begin{alignedat}{3}6&=2^{1}(2^{2}-1)&&=1+2+3,\\[8pt]28&=2^{2}(2^{3}-1)&&=1+2+3+4+5+6+7\\&&&=1^{3}+3^{3}\\[8pt]496&=2^{4}(2^{5}-1)&&=1+2+3+\cdots +29+30+31\\&&&=1^{3}+3^{3}+5^{3}+7^{3}\\[8pt]8128&=2^{6}(2^{7}-1)&&=1+2+3+\cdots +125+126+127\\&&&=1^{3}+3^{3}+5^{3}+7^{3}+9^{3}+11^{3}+13^{3}+15^{3}\\[8pt]33550336&=2^{12}(2^{13}-1)&&=1+2+3+\cdots +8189+8190+8191\\&&&=1^{3}+3^{3}+5^{3}+\cdots +123^{3}+125^{3}+127^{3}\end{alignedat}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/745441a19702e99f618b24c0d40a28097d08982f)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{3}]{3N}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a3a6538e804a2716576609825734301136d56b6d)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{5}]{2N}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5871ef69c5781b0267353a19bfa37d91b90e0c28)

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{6}]{2N}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a570fdf593bde2781184260ec28f5c917fd3d452)