Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bijection

View on Wikipedia

| Function |

|---|

| x ↦ f (x) |

| History of the function concept |

| Types by domain and codomain |

| Classes/properties |

| Constructions |

| Generalizations |

| List of specific functions |

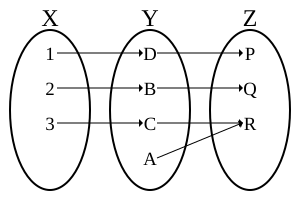

In mathematics, a bijection, bijective function, or one-to-one correspondence is a function between two sets such that each element of the second set (the codomain) is the image of exactly one element of the first set (the domain). Equivalently, a bijection is a relation between two sets such that each element of either set is paired with exactly one element of the other set.

A function is bijective if it is invertible; that is, a function is bijective if and only if there is a function the inverse of f, such that each of the two ways for composing the two functions produces an identity function: for each in and for each in

For example, the multiplication by two defines a bijection from the integers to the even numbers, which has the division by two as its inverse function.

A function is bijective if and only if it is both injective (or one-to-one)—meaning that each element in the codomain is mapped from at most one element of the domain—and surjective (or onto)—meaning that each element of the codomain is mapped from at least one element of the domain. The term one-to-one correspondence must not be confused with one-to-one function, which means injective but not necessarily surjective.

The elementary operation of counting establishes a bijection from some finite set to the first natural numbers (1, 2, 3, ...), up to the number of elements in the counted set. It results that two finite sets have the same number of elements if and only if there exists a bijection between them. More generally, two sets are said to have the same cardinal number if there exists a bijection between them.

A bijective function from a set to itself is also called a permutation,[1] and the set of all permutations of a set forms its symmetric group.

Some bijections with further properties have received specific names, which include automorphisms, isomorphisms, homeomorphisms, diffeomorphisms, permutations, and most geometric transformations. Galois correspondences are bijections between sets of mathematical objects of apparently very different nature.

Definition

[edit]For a binary relation pairing elements of set X with elements of set Y to be a bijection, four properties must hold:

- each element of X must be paired with at least one element of Y,

- no element of X may be paired with more than one element of Y,

- each element of Y must be paired with at least one element of X, and

- no element of Y may be paired with more than one element of X.

Satisfying properties (1) and (2) means that a pairing is a function with domain X. It is more common to see properties (1) and (2) written as a single statement: Every element of X is paired with exactly one element of Y. Functions which satisfy property (3) are said to be "onto Y " and are called surjections (or surjective functions). Functions which satisfy property (4) are said to be "one-to-one functions" and are called injections (or injective functions).[2] With this terminology, a bijection is a function which is both a surjection and an injection, or using other words, a bijection is a function which is both "one-to-one" and "onto".[3]

Examples

[edit]Batting line-up of a baseball or cricket team

[edit]Consider the batting line-up of a baseball or cricket team (or any list of all the players of any sports team where every player holds a specific spot in a line-up). The set X will be the players on the team (of size nine in the case of baseball) and the set Y will be the positions in the batting order (1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc.) The "pairing" is given by which player is in what position in this order. Property (1) is satisfied since each player is somewhere in the list. Property (2) is satisfied since no player bats in two (or more) positions in the order. Property (3) says that for each position in the order, there is some player batting in that position and property (4) states that two or more players are never batting in the same position in the list.

Seats and students of a classroom

[edit]In a classroom there are a certain number of seats. A group of students enter the room and the instructor asks them to be seated. After a quick look around the room, the instructor declares that there is a bijection between the set of students and the set of seats, where each student is paired with the seat they are sitting in. What the instructor observed in order to reach this conclusion was that:

- Every student was in a seat (there was no one standing),

- No student was in more than one seat,

- Every seat had someone sitting there (there were no empty seats), and

- No seat had more than one student in it.

The instructor was able to conclude that there were just as many seats as there were students, without having to count either set.

More mathematical examples

[edit]

- For any set X, the identity function 1X: X → X, 1X(x) = x is bijective.

- The multiplicative inverse function gives a bijection of the unit interval (0, 1) with the semi-infinite interval (1, +∞).

- The function f: R → R, f(x) = 2x + 1 is bijective, since for each y there is a unique x = (y − 1)/2 such that f(x) = y. More generally, any linear function over the reals, f: R → R, f(x) = ax + b (where a is non-zero) is a bijection. Each real number y is obtained from (or paired with) the real number x = (y − b)/a.

- The function f: R → (−π/2, π/2), given by f(x) = arctan(x) is bijective, since each real number x is paired with exactly one angle y in the interval (−π/2, π/2) so that tan(y) = x (that is, y = arctan(x)). If the codomain (−π/2, π/2) was made larger to include an integer multiple of π/2, then this function would no longer be onto (surjective), since there is no real number which could be paired with the multiple of π/2 by this arctan function.

- The exponential function, g: R → R, g(x) = ex, is not bijective: for instance, there is no x in R such that g(x) = −1, showing that g is not onto (surjective). However, if the codomain is restricted to the positive real numbers , then g would be bijective; its inverse (see below) is the natural logarithm function ln.

- The function h: R → R+, h(x) = x2 is not bijective: for instance, h(−1) = h(1) = 1, showing that h is not one-to-one (injective). However, if the domain is restricted to , then h would be bijective; its inverse is the positive square root function.

- By Schröder–Bernstein theorem, given any two sets X and Y, and two injective functions f: X → Y and g: Y → X, there exists a bijective function h: X → Y.

Inverses

[edit]A bijection f with domain X (indicated by f: X → Y in functional notation) also defines a converse relation starting in Y and going to X (by turning the arrows around). The process of "turning the arrows around" for an arbitrary function does not, in general, yield a function, but properties (3) and (4) of a bijection say that this inverse relation is a function with domain Y. Moreover, properties (1) and (2) then say that this inverse function is a surjection and an injection, that is, the inverse function exists and is also a bijection. Functions that have inverse functions are said to be invertible. A function is invertible if and only if it is a bijection.

Stated in concise mathematical notation, a function f: X → Y is bijective if and only if it satisfies the condition

- for every y in Y there is a unique x in X with y = f(x).

Continuing with the baseball batting line-up example, the function that is being defined takes as input the name of one of the players and outputs the position of that player in the batting order. Since this function is a bijection, it has an inverse function which takes as input a position in the batting order and outputs the player who will be batting in that position.

Composition

[edit]

The composition of two bijections and is a bijection, whose inverse is given by is .

Conversely, if the composition of two functions is bijective, it only follows that f is injective and g is surjective.

Cardinality

[edit]If X and Y are finite sets, then there exists a bijection between the two sets X and Y if and only if X and Y have the same number of elements. Indeed, in axiomatic set theory, this is taken as the definition of "same number of elements" (equinumerosity), and generalising this definition to infinite sets leads to the concept of cardinal number, a way to distinguish the various sizes of infinite sets.

Properties

[edit]- A function f: R → R is bijective if and only if its graph meets every horizontal and vertical line exactly once.

- If X is a set, then the bijective functions from X to itself, together with the operation of functional composition (), form a group, the symmetric group of X, which is denoted variously by S(X), SX, or X! (X factorial).

- Bijections preserve cardinalities of sets: for a subset A of the domain with cardinality |A| and subset B of the codomain with cardinality |B|, one has the following equalities:

- |f(A)| = |A| and |f−1(B)| = |B|.

- If X and Y are finite sets with the same cardinality, and f: X → Y, then the following are equivalent:

- f is a bijection.

- f is a surjection.

- f is an injection.

- For a finite set S, there is a bijection between the set of possible total orderings of the elements and the set of bijections from S to S. That is to say, the number of permutations of elements of S is the same as the number of total orderings of that set—namely, n!.

Category theory

[edit]Bijections are precisely the isomorphisms in the category Set of sets and set functions. However, the bijections are not always the isomorphisms for more complex categories. For example, in the category Grp of groups, the morphisms must be homomorphisms since they must preserve the group structure, so the isomorphisms are group isomorphisms which are bijective homomorphisms.

Generalization to partial functions

[edit]The notion of one-to-one correspondence generalizes to partial functions, where they are called partial bijections, although partial bijections are only required to be injective. The reason for this relaxation is that a (proper) partial function is already undefined for a portion of its domain; thus there is no compelling reason to constrain its inverse to be a total function, i.e. defined everywhere on its domain. The set of all partial bijections on a given base set is called the symmetric inverse semigroup.[4]

Another way of defining the same notion is to say that a partial bijection from A to B is any relation R (which turns out to be a partial function) with the property that R is the graph of a bijection f:A′→B′, where A′ is a subset of A and B′ is a subset of B.[5]

When the partial bijection is on the same set, it is sometimes called a one-to-one partial transformation.[6] An example is the Möbius transformation simply defined on the complex plane, rather than its completion to the extended complex plane.[7]

Gallery

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Hall 1959, p. 3

- ^ There are names associated to properties (1) and (2) as well. A relation which satisfies property (1) is called a total relation and a relation satisfying (2) is a single valued relation.

- ^ "Bijection, Injection, And Surjection | Brilliant Math & Science Wiki". brilliant.org. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ Christopher Hollings (16 July 2014). Mathematics across the Iron Curtain: A History of the Algebraic Theory of Semigroups. American Mathematical Society. p. 251. ISBN 978-1-4704-1493-1.

- ^ Francis Borceux (1994). Handbook of Categorical Algebra: Volume 2, Categories and Structures. Cambridge University Press. p. 289. ISBN 978-0-521-44179-7.

- ^ Pierre A. Grillet (1995). Semigroups: An Introduction to the Structure Theory. CRC Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-8247-9662-4.

- ^ John Meakin (2007). "Groups and semigroups: connections and contrasts". In C.M. Campbell; M.R. Quick; E.F. Robertson; G.C. Smith (eds.). Groups St Andrews 2005 Volume 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 367. ISBN 978-0-521-69470-4. preprint citing Lawson, M. V. (1998). "The Möbius Inverse Monoid". Journal of Algebra. 200 (2): 428–438. doi:10.1006/jabr.1997.7242.

References

[edit]This topic is a basic concept in set theory and can be found in any text which includes an introduction to set theory. Almost all texts that deal with an introduction to writing proofs will include a section on set theory, so the topic may be found in any of these:

- Hall, Marshall Jr. (1959). The Theory of Groups. MacMillan.

- Wolf (1998). Proof, Logic and Conjecture: A Mathematician's Toolbox. Freeman.

- Sundstrom (2003). Mathematical Reasoning: Writing and Proof. Prentice-Hall.

- Smith; Eggen; St.Andre (2006). A Transition to Advanced Mathematics (6th Ed.). Thomson (Brooks/Cole).

- Schumacher (1996). Chapter Zero: Fundamental Notions of Abstract Mathematics. Addison-Wesley.

- O'Leary (2003). The Structure of Proof: With Logic and Set Theory. Prentice-Hall.

- Morash. Bridge to Abstract Mathematics. Random House.

- Maddox (2002). Mathematical Thinking and Writing. Harcourt/ Academic Press.

- Lay (2001). Analysis with an introduction to proof. Prentice Hall.

- Gilbert; Vanstone (2005). An Introduction to Mathematical Thinking. Pearson Prentice-Hall.

- Fletcher; Patty. Foundations of Higher Mathematics. PWS-Kent.

- Iglewicz; Stoyle. An Introduction to Mathematical Reasoning. MacMillan.

- Devlin, Keith (2004). Sets, Functions, and Logic: An Introduction to Abstract Mathematics. Chapman & Hall/ CRC Press.

- D'Angelo; West (2000). Mathematical Thinking: Problem Solving and Proofs. Prentice Hall.

- Cupillari (1989). The Nuts and Bolts of Proofs. Wadsworth. ISBN 9780534103200.

- Bond. Introduction to Abstract Mathematics. Brooks/Cole.

- Barnier; Feldman (2000). Introduction to Advanced Mathematics. Prentice Hall.

- Ash. A Primer of Abstract Mathematics. MAA.