Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Blockade runner

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (July 2011) |

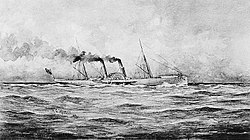

A blockade runner is a merchant vessel used for evading a naval blockade of a port or strait. It is usually light and fast, using stealth and speed rather than confronting the blockaders in order to break the blockade. Blockade runners usually transport cargo, for example bringing food or arms to a blockaded city. They have also carried mail in an attempt to communicate with the outside world.

Blockade runners are often the fastest ships available, and come lightly armed and armored. Their operations are quite risky since blockading fleets would not hesitate to fire on them. However, the potential profits (economically or militarily) from a successful blockade run are tremendous, so blockade-runners typically had excellent crews. Although having modus operandi similar to that of smugglers, blockade-runners are often operated by states' navies as part of the regular fleet; states having operated them include the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War, and Germany during the World Wars.

In history

[edit]Ancient Greece, Peloponnesian War

[edit]There were numerous blockades and attempts at blockade running during the Peloponnesian War. With his fleet blockaded, Leon of Salamis dispatched blockade runners to seek reinforcements from Athens.

Ancient Rome, Punic Wars

[edit]During the Punic Wars, the Carthaginian Empire attempted to evade Roman navy blockades of its ports and strongholds. At one point, blockade runners brought in the only food reaching the city of Carthage.[1][2]

Middle age

[edit]During the 14th century, while Queen Margaret I of Denmark's forces were besieging Stockholm, the blockade runners who came to be known as the Victual Brotherhood engaged in war at sea and shipped provisions to keep the city supplied.

American Revolutionary War

[edit]Blockade runners in the American Revolution eluded the British naval blockades in order to supply resources to the army. French naval aid was vital.

American Civil War

[edit]

During the American Civil War, blockade running became a major enterprise for the Confederacy due to the Union blockade as part of the Anaconda Plan to cut off the Confederacy's overseas trade. Twelve major ports and approximately 3,500 miles of coastline along the Confederacy were patrolled by roughly 500 Union Navy ships.[citation needed]

The United Kingdom played a major role in Confederate blockade running. British merchants had conducted significant amounts of trade with the South prior to the war, and were suffering from the Lancashire Cotton Famine. The British Empire also controlled many of the neutral ports in the Caribbean, most notably the Bahamas and Bermuda. In concert with Confederate interests, British investors ordered the construction of steamships that were longer, narrower and considerably faster than most of the conventional steamers guarding the American coastline, thus enabling them to outmaneuver and outrun blockaders. Among the more notable was the CSS Advance that completed more than 20 successful runs through the Union blockade before being captured.[3]

These vessels brought badly needed supplies, especially firearms, and Confederate mail. The blockade played a major role in the Union's victory over the Confederate states, though historians have estimated the supplies brought by blockade runners to the Confederacy lengthened the duration of the war by up to two years.[4][5] By the end of the American Civil War, Union warships had captured more than 1,100 blockade runners and had destroyed or run aground another 355.[6][7]

Cretan Revolt (1866–1869)

[edit]Greek blockade runners supplied the Christians during the Cretan revolt (1866–1869). Names of the ships include: Arkadion (named after the Arkadi Monastery, sunk by the Ottoman sloop-of-war Izzedin in August 1867);[8] Hydra; Panhellenion; and Enosis (Unification), which was detained in Syros by Hobart Pasha in December 1868, just about the time the rebellion collapsed.

Prohibition era

[edit]World War I

[edit]During World War I the Central Powers, most notably Germany, were blockaded by the Entente Powers. In particular the North Sea blockade made it nearly impossible for surface ships to leave Germany for the then neutral United States and other locations.

The blockade was run with cargo submarines, also called merchant submarines, Deutschland and Bremen, which reached the then neutral United States.[9]

The Marie successfully ran the British North Sea blockade and docked, heavily damaged, in Batavia, Dutch East Indies (now called Jakarta) on May 13, 1916.[10]

In 1917 Germany tried unsuccessfully to supply their forces in Africa by sending Zeppelin LZ104.

World War II

[edit]Axis blockade runners

[edit]

On the outbreak of war, the Royal Navy imposed a naval blockade of Germany. The fall of France provided the German occupying forces with access to the French Atlantic coast and between 1940 and 1942, many blockade running trips succeeded in delivering cargoes of critical war supplies - especially crude rubber - through the port of Bordeaux; a trade that increased with the entry of Japan into the war in December 1941. Allied attempts to disrupt these operations initially had only a limited effect; as in Operation Frankton. From 1943 improved Allied air superiority over the Bay of Biscay rendered blockade running by surface ships effectively impossible. By some counts, during the war Germans sent 32 (surface) blockade runners to Japan, only 16 of them reaching their destination. Later in the war, most of the trade between Germany and Japan was by cargo submarine.[11]

Italian ships, interned in Spain after Italy entered the war in June 1940, crossed the Bay of Biscay to Bordeaux and some of them, such as Fidelitas and Eugenio C, dashed through the English Channel bound for Germany and Norway.[12][13]

To transfer technology to Imperial Japan, on 25 March 1945 Nazi Germany dispatched a submarine, U-234, to sail to Japan. Germany surrendered before it arrived. The Japanese submarine I-8 completed a similar mission.

The German ship Ramses was in China when the war started. On Nov. 23, 1942, she attempted to sail from Batavia (now Jakarta), to Bordeaux with a cargo of rubber. The hope was that maintaining a sharp 24-hour lookout they could evade the Allied blockade.[14] HMAS Adelaide (1918) caught and sank her.

A small number of planes succeeded in flying between the Axis-controlled Europe and the Japanese-controlled parts of Asia. The first known flight was by an Italian Savoia-Marchetti SM.75 Marsupiale, which flew in July 1942, according to various sources, either from Zaporozhye to Baotou or from Rhodes Island to Rangoon.[11] Later, German Junkers Ju 290-A aircraft prepared for (or, according to some sources, completed) similar flights.[11]

Allied blockade runners

[edit]During World War II, trade between Sweden (which remained neutral throughout the war) and Britain was severely curtailed by the German blockade of the Skagerrak straits between Norway and the northern tip of Denmark. In order to import vital materiel from Sweden, such as ball bearings for the British aircraft industry, five Motor Gun Boats, such as the Gay Viking, were converted into blockade runners, using winter darkness and high speed to penetrate the German maritime blockade. Larger Norwegian ships succeeded in escaping through the blockade to Britain in Operation Rubble but later attempts failed.

Modern era

[edit]In modern times, tracking equipment such as radar, sonar, and reconnaissance satellites make evading a total blockade by a world power nearly impossible.[citation needed] Drug smugglers and groups like the Tamil Tigers are able to run blockades due to the partial nature of the blockade, or because the navy imposing the blockade is weak and under-equipped. Reminiscent of earlier German attempts, drug smugglers have used semi-submersibles (narco-submarines) in their smuggling operations.

See also

[edit]- Blockade runners of the American Civil War

- Postage stamps and postal history of the Confederate States § Blockade runners

- List of ships captured in the 19th century § American Civil War

- Airbridge (logistics), the route and means of delivering material by an airlift, sometimes across blockades

- CSS Lark

- Merchant submarine, first invented for blockade running in World War I

- Type 4 Ka-Tsu

- Hobart Pasha

- Swedish overseas trade during World War II

- Tantive IV, fictional spaceship in the Star Wars film series, referred to as a blockade runner

References

[edit]- ^ Kern, Paul Bentley: Ancient siege warfare (p. 294)

- ^ "Hamilcar Barca - Livius". www.livius.org. Archived from the original on 2013-01-22. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- ^ Wyllie, 2007 p.22

- ^ David Keys (24 June 2014). "Historians reveal secrets of UK gun-running which lengthened the American civil war by two years". The Independent.

- ^ Paul Hendren (April 1933). "The Confederate Blockade Runners". United States Naval Institute.

- ^ Scharf 1996, pp. 479–480.

- ^ "Confederate blockade mail". Richard Frajola, philatelist and historian. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ^ Morning Post, London. 5 September 1867 citing Official Ottoman report of the incident.

- ^ "German U-boat WWI Blockade Runners « War and Game". 3 March 2008. Archived from the original on 3 March 2008.

- ^ "SURVIVED BRITISH SHELLS.; German Blockade Runner, Almost a Sieve, Sailed from Africa to Java". The New York Times. 5 November 1916 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ a b c Harvey, A. D. (1992), Collision of Empires: Britain in Three World Wars, 1793–1945, Continuum, pp. 581–582, ISBN 1852850787

- ^ Notarangelo, Rolando (1977). Navi mercantili perdute (in Italian). Roma: Ufficio Storico della Marina Militare. p. 185.

- ^ Notarangelo (1977), p. 176

- ^ "Ahoy - Mac's Web Log - Blockade Runner Ramses". ahoy.tk-jk.net.

Bibliography

[edit]- Coker, P. C., III. Charleston's Maritime Heritage, 1670-1865: An Illustrated History. Charleston, S.C.: Coker-Craft, 1987. 314 pp.

- Scharf, J. Thomas (1996) [1887]. History of the Confederate States navy from its organization to the surrender of its last vessel. New York: Gramercy Books. ISBN 0-517-18336-6.

- Wyllie, Arthur (2007). The Confederate States Navy.

Lulu.com. p. 466. ISBN 978-0-615-17222-4.[self-published source] Url1

Blockade runner

View on GrokipediaA blockade runner is a swift, low-profile merchant vessel optimized for evading naval blockades during wartime, relying on speed, stealth, and shallow draft to transport cargo through restricted waters.[1][2] These ships were prominently utilized in the American Civil War (1861–1865), where Confederate operators employed them to import arms, ammunition, and medical supplies into Southern ports while exporting cotton to neutral territories such as Bermuda, Nassau, and Cuba, thereby circumventing the Union Navy's coastal blockade proclaimed by President Abraham Lincoln in April 1861.[3][1] Typically constructed as side-wheel or screw steamers of 400 to 600 tons, blockade runners featured elongated hulls—often six to nine times their beam—painted in dull lead-gray for nocturnal camouflage, telescopic smokestacks to reduce silhouette, feathering paddles or propellers for quiet operation, and fuels like smokeless anthracite coal to minimize detection.[1][2] Speeds of 9 to 13 knots enabled daring nighttime dashes, guided by expert pilots navigating via soundings and landmarks over routes spanning 500 to 600 miles.[2] Despite high risks and rewards—crews earning thousands in gold per voyage—their operations sustained Confederate logistics and morale, with estimates indicating two-thirds of early attempts succeeding and individual ships like the R. E. Lee completing 21 runs carrying thousands of cotton bales valued at millions.[1][2] However, as Union forces expanded and tightened the blockade, capturing over 1,100 runners and sinking or destroying hundreds more, the flow of goods dwindled, contributing to the Confederacy's eventual resource exhaustion by 1865.[3][2]

Definition and Characteristics

Core Definition

A blockade runner is a vessel, typically a ship, employed to evade a naval blockade of a port, strait, or coastline by transporting cargo such as munitions, medical supplies, or export commodities to or from the blockaded area.[4][5] These operations aim to sustain besieged forces or economies against the blockading power's efforts to isolate and starve them of resources through maritime interdiction.[1] Unlike warships designed for combat, blockade runners prioritize evasion over confrontation, relying on superior speed and stealth to minimize detection and engagement risks.[6] Blockade runners are generally constructed as lightweight, fast-steaming vessels with low freeboard, shallow drafts, and minimal superstructure to reduce visibility and enhance maneuverability in shallow or confined waters.[2][1] In the 19th century, common designs included side-wheel steamers of 400 to 600 tons, elongated hulls with sharp bows, and engines optimized for bursts of high speed, often exceeding 10 knots to outpace pursuers.[1] These features enabled runners to approach blockaded harbors at night, using local knowledge of channels and pilotage to navigate past patrols.[2] Cargo capacity was limited to prioritize speed, with high-value, compact goods like arms or cotton preferred for profitability.[1] The practice is inherently commercial and opportunistic, frequently undertaken by private owners or firms under government sanction, such as letters of marque, to generate profit amid wartime scarcity.[2] Success depended on factors including blockade enforcement stringency, weather conditions, and intelligence on patrol patterns, with runners often staging from neutral ports like Bermuda or Nassau for transshipment.[7] Historical efficacy varied; during the American Civil War (1861–1865), approximately 8,000 successful runs supplied the Confederacy despite Union naval efforts, though losses mounted as blockades tightened.[1] Blockade running exemplifies asymmetric maritime strategy, where smaller, agile assets challenge superior naval forces through guile and velocity rather than direct battle.[2]