Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

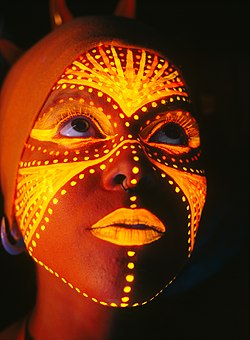

Body painting

View on Wikipedia

Body painting is a form of body art where artwork is painted directly onto the human skin. Unlike tattoos and other forms of body art, body painting is temporary, lasting several hours or sometimes up to a few weeks (in the case of mehndi or "henna tattoos" about two weeks). Body painting that is limited to the face is known as face painting. Body painting is also referred to as (a form of) "temporary tattoo". Large scale or full-body painting is more commonly referred to as body painting, while smaller or more detailed work can sometimes be referred to as temporary tattoos.

Indigenous

[edit]

Body painting with a grey or white paint made from natural pigments including clay, chalk, ash and cattle dung is traditional in many tribal cultures. Often worn during cultural ceremonies, it is believed to assist with the moderation of body heat and the use of striped patterns may reduce the incidence of biting insects. It still survives in this ancient form among Indigenous Australians and in parts of Africa and Southeast Asia,[1] as well as in New Zealand and the Pacific islands. A semi-permanent form of body painting known as Mehndi, using dyes made of henna leaves (hence also known rather erroneously as "henna tattoo"), is practiced in India, especially on brides. Since the late 1990s, Mehndi has become popular amongst young women in the Western world.

Many indigenous peoples of Central and South America paint jagua tattoos, or designs with Genipa americana juice on their bodies. Indigenous peoples of South America traditionally use annatto, huito, or wet charcoal to decorate their faces and bodies. Huito is semi-permanent, and it generally takes weeks for this black dye to fade.[2]

Western

[edit]

Body painting is not always large pieces on fully nude bodies, but can involve smaller pieces on displayed areas of otherwise clothed bodies. There has been a revival of body painting in Western society since the 1960s, in part prompted by the liberalization of social mores regarding nudity and often comes in sensationalist or exhibitionist forms.[3] Even today there is a constant debate about the legitimacy of body painting as an art form. The current modern revival could be said to date back to the 1933 World's Fair in Chicago when Max Factor Sr. and his model Sally Rand were arrested for causing a public disturbance when he body-painted her with his new make-up formulated for Hollywood films.[4] Body art today evolves to the works more directed towards personal mythologies, as Jana Sterbak, Rebecca Horn, Michel Platnic, Youri Messen-Jaschin or Javier Perez.

Body painting is sometimes used as a method of gaining attention in political protests, for instance those by PETA against Burberry.[citation needed]

Joanne Gair is a body paint artist whose work appeared for the tenth consecutive year in the 2008 Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue. She came to prominence with an August 1992 Vanity Fair Demi's Birthday Suit cover of Demi Moore.[5][6] Her Disappearing Model was part of an episode of Ripley's Believe It or Not!.[7]

Festivals

[edit]

Body painting festivals happen annually across the world, bringing together professional body painters and keen amateurs. Body painting can also be seen at some football matches, at rave parties, and at certain festivals. The World Bodypainting Festival is a three-day festival which originated in 1998 and which has been held in Klagenfurt, Austria since 2017. Participants attend from over fifty countries and the event has more than 20,000 visitors; the associated World Bodypainting Association promotes the art of bodypainting.

Body painting festivals that take place in North America include the North American Body Painting Championship, Face and Body Art International Convention in Orlando, Florida, Bodygras Body Painting Competition in Nanaimo, BC and the Face Painting and Body Art Convention in Las Vegas, Nevada.

Australia also has a number of body painting festivals, most notably the annual Australian Body Art Festival in Eumundi, Queensland[8] and the Australian Body Art Awards.[9]

In Italy, the Rabarama Skin Art Festival (held every year during the Summer and Autumn, with a tour in the major Italian cities), is a different event focused on the artistic side of body painting, highlighting the emotional impact of the painted body in a live performance[10] more than the decorative and technical aspects of it. This particular form of creative art is known as "Skin Art".[11]

Fine art

[edit]The 1960s supermodel Veruschka has inspired bodypaint artists, after influential images of her appeared in the 1986 book Transfigurations by photographer Holger Trulzsch.[12] Other well-known works include Serge Diakonoff's books A Fleur de Peau[citation needed] and Diakonoff and Joanne Gair's Paint a licious. More recently Dutch art photographer Karl Hammer has created combinations of body painting and narrative art (fantastic realism).[citation needed]

Following the already established trend in Western Europe, body painting has become more widely accepted in the United States since the early 1990s. In 2006 the first gallery dedicated exclusively to fine art body painting was opened in New Orleans by World Bodypainting Festival Champion and Judge, Craig Tracy. The Painted Alive Gallery is on Royal Street in the French Quarter.[citation needed] In 2009, a popular late night talk show Last Call with Carson Daly on NBC network, featured a New York-based artist Danny Setiawan who creates reproductions of masterpieces by famous artists such as Salvador Dalí, Vincent van Gogh, and Gustav Klimt on human bodies aiming to make fine art appealing for his contemporaries who normally would not consider themselves as art enthusiasts.[citation needed]

Since 2005 the Australian visual artist Emma Hack has been creating photographs of painted naked human bodies that visually merge with a patterned background wall inspired by the wallpaper designs of Florence Broadhurst. Hack is best known for the Gotye music video for the song "Somebody That I Used to Know", which uses stop-motion animation body painting and has received over 800 million views on YouTube.[13] Hack now creates her own canvas backgrounds and her work is often featured with live birds, representing nature. Hack's artworks are exhibited worldwide.

Michel Platnic is a French–Israeli contemporary visual artist. He is known for his "living paintings". He uses multiple mediums including photography, video, performance body-painting and painting . Platnic builds three-dimensional cinema sets that are a backdrop for his video and photography works and then he paints directly on the body of the living models he places within the sets. Using this technique, Platnic brought to life several scenes of paintings made famous by artists Francis Bacon, Egon Schiele, David Hockney and Lucian Freud and placed them in a different context.[15] Los Angeles artist, Paul Roustan, is known for his work in body painting and photography which spans both the fine art and commercial worlds. His body painting has received numerous awards, including winner of the North American Body Paint Championships.[16]

Trina Merry is a body painter known for camouflaging models into settings, backgrounds and, in her "Lust of Currency" series, famous paintings. Merry's collection was exhibited during Miami Art Basel in 2017[17] and at the Superfine! New York art fair in May 2018.[18][19]

Peruvian artist Cecilia Paredes is known for her style of painting her own body to camouflage herself against complex floral backgrounds and natural landscapes.[20]

In the commercial arena

[edit]

Many artists work professionally as body painters for television commercials, such as the Natrel Plus campaign featuring models camouflaged as trees. Stills advertising also uses body painting with hundreds of body painting looks on the pages of the world's magazines every year. Body painters also work frequently in the film arena, especially in science fiction with an increasing number of elaborate alien creations being body painted.[citation needed]

The Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue, published annually, has frequently featured a section in which body-painted models appear to be wearing swimsuits or sports jerseys. Playboy magazine has frequently made use of body painted models. In the 2005 Playmates at Play at the Playboy Mansion calendar, all the Playmates appeared in bikinis apart from Playmates Karen McDougal and Hiromi Oshima, who instead had painted-on bikinis.[citation needed]

The success of body painting has led to many notable international competitions and a specific trade magazine (Illusion Magazine)[22] for this industry, showcasing work around the world.

Face painting

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2012) |

Face painting is the artistic application of nontoxic paint to a person's face. The practice dates from Paleolithic times and has been used for ritual purposes, such as coming-of-age ceremonies and funeral rites, as well as for hunting. Materials such as clay, chalk or henna have been used, typically mixed with pigments extracted from leaves, fruits or berries and sometimes with oils or fats.[23]

Many peoples around the world practice face painting in modern times. This includes indigenous peoples in places such as Australia, Papua New Guinea, Polynesia and Melanesia. Some tribes in Sub-Saharan Africa use the technique during rituals and festivals, and many of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America now use it for ceremonies, having previously also used it for hunting and warfare. In India it is used in folk dances and temple festivals, such as in Kathakali performances, and Mehndi designs are used at weddings. It is also used by Japanese Geisha and Chinese opera singers.[24] Women in Madagascar paint their faces with designs featuring stars, flowers and leaves using contrasting yellow and white wood paste called masonjoany.[25]

In some forms of Western folk dance, such as Border Morris, the faces of the dancers are painted with a black pigment in a tradition that goes back to the Middle Ages. In the 18th century cosmetic face painting became popular with men and women of the aristocracy and the nouveau riche,[26] but it died out in Western culture after the fall of the French aristocracy. During the 19th century blackface theatrical makeup gained popularity when it was used by non-black performers to represent black people, typically in a minstrel show.[27] Its use ended in the United States with the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.[28] At about the same time the hippie movement adopted face painting,[29] and it was common for young people to decorate their cheeks with flowers or peace symbols at anti-war demonstrations.

Skeletal face painting has become common at Day of the Dead celebrations in Mexico and in the United States, especially since the 2010s.[30]

In contemporary Western culture face painting has become an art form, with artists displaying their work at festivals and in competitions and magazines. Other western users include actors and clowns, and it continues to be used as a form of camouflage amongst hunters and the military. It is also found at entertainments for children and sports events.[31]

For several decades it has been a common entertainment at county fairs, large open-air markets (especially in Europe and the Americas), and other locations that attract children and adolescents. Face painting is very popular among children at theme parks, parties and festivals throughout the Western world.[citation needed] Though the majority of face painting is geared towards children, many teenagers and adults enjoy being painted for special events, such as sports events (to give support to their team or country) or charity fund raisers.[citation needed]

In the military

[edit]

It is common for soldiers in combat to paint their faces and other exposed body parts in colors such as green, tan, and loam as camouflage. In various South American armies, it is a tradition to use face paint on parade in respect to the indigenous tribes.[32]

Temporary tattoos

[edit]As well as paint, temporary tattoos can be used to decorate the body. "Glitter tattoos" are made by applying a clear, cosmetic-grade glue (either freehand or through a stencil) on the skin and then coating it with cosmetic-grade glitter. They can last up to a week depending on the model's body chemistry.

Foil metallic temporary tattoos are a variation of decal-style temporary tattoos, printed using foil stamping technique instead of ink. On the front side, the foil design is printed as a mirror image in order to be viewed in the right direction once it is applied to the skin. Each metallic tattoo is protected by a transparent protective film.

Body paints

[edit]

Modern water-based face and body paints are made according to stringent guidelines, meaning these are non-toxic, usually non-allergenic, and can easily be washed away. Temporary staining may develop after use, but it will fade after normal washing. These are either applied with hands, paint brush, and synthetic sponges or natural sea sponge, or alternatively with an airbrush.

Contrary to the popular myth perpetuated by the James Bond film Goldfinger, a person is not asphyxiated if their whole body is painted.[33]

Liquid latex may also be used as body paint. Aside the risk of contact allergy, wearing latex for a prolonged period may cause heat stroke by inhibiting perspiration and care should be taken to avoid the painful removal of hair when the latex is pulled off.

The same precautions that apply to cosmetics should be observed. If the skin shows any sign of allergy from a paint, its use should immediately be ceased. Moreover, it should not be applied to damaged, inflamed or sensitive skin. If possible, a test for allergic reaction should be performed before use. Special care should be paid to the list of ingredients, as certain dyes are not approved by the US FDA for use around the eye area—generally those associated with certain reddish colorants, as CI 15850 or CI 15985—or on lips, generally blue, purple or some greens containing CI 77007.[34][35] More stringent regulations are in place in California regarding the amount of permissible lead on cosmetic additives, as part of Proposition 65.[36] In the European Union, all colorants listed under a CI number are allowed for use on all areas. Any paints or products which have not been formulated for use on the body should never be used for body or face painting, as these can result in serious allergic reactions.

As for Mehndi, natural brown henna dyes are safe to use when mixed with ingredients such as lemon juice. Another option is Jagua, a dark indigo plant-based dye that is safe to use on the skin and is approved for cosmetic use in the EU.

Body marbling

[edit]

Hands and faces can be marbled temporarily for events such as festivals, using a painting process similar to traditional paper marbling, in which paint is floated on water and transferred to a person's skin. Unlike the traditional oil-based technique for paper, neon or ultraviolet reactive colours are typically used, and the paint is water-based and non-toxic.[37][38]

Hand art

[edit]"Hand art" is the application of make-up or paint to a hand to make it appear like an animal or other object. Some hand artists, like Guido Daniele, produce images that are trompe-l'œil representations of wild animals painted on people's hands.

Hand artists work closely with hand models. Hand models can be booked through specialist acting and modeling agencies usually advertising under "body part model" or "hands and feet models".

Body glitter

[edit]The application of glitter and reflective ornaments to a woman's breasts, often in the shape of a bikini top or crop top and sometimes alongside nipple tassels, is known as glitter boobs. Like body paint, this decoration is popular with festivalgoers.[39][40] Buttocks are also sometimes decorated in a similar manner,[41] and the adornment of the a woman's pubic area is known as a vajazzle.

Media

[edit]Body painting features in various media. The popular TV variety show, Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In, featured bodies painted with comedic phrases and jokes during transitions. The Pillow Book, a 1996 film by Peter Greenaway, is centred on body painting. The 1990 American film Where the Heart Is featured several examples of models who were painted to blend into elaborate backdrops as trompe-l'œil. Skin Wars is a body painting reality competition hosted by Rebecca Romijn that premiered on Game Show Network on August 6, 2014.

See also

[edit]- Body art

- Corpse paint

- Make up

- Mehndi (so-called henna tattoos)

References

[edit]- ^ "'Zebra' tribal bodypaint cuts fly bites 10-fold: study". Phys.org. 16 January 2019.

- ^ Montañez R., Dinhora (2013). Diario del Huila (ed.). Body painting, el arte de la poesía corporal: Sobre el trabajo de Mao Mix R. Neiva.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Body Painting: History, Origins, Types, Methods, Festivals: Tribal Art". Visual-Arts-Cork.com. Retrieved 2010-09-10.

- ^ Basten, Fred E. (2012). Max Factor: The Man Who Changed the Faces of the World. New York: Arcade Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61145-135-1.

- ^ "Make-Up Illusion by Joanne Gair". Archived from the original on 2007-12-21. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

- ^ "Body Painting: Masterpieces by Joanne Gair". Art MOCO: The Modern and Contemporary Art Blog. 2007-07-22. Archived from the original on 2008-02-05. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

- ^ "Joanne Gair: The Art of Illusion". Retrieved 2009-04-23.

- ^ "Australian Body Art Festival". Australian Body Art Festival. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ "Australian Body Art Awards". Australian Body Art Awards. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ Kryolan Italia (4 October 2016). "Finale 2016 del Rabarama Skin Art Festival, video TG". Archived from the original on 2021-11-18. Retrieved 22 January 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Rabarama Skin Art: body painting d'arte festival in Italia". rabaramaskinartfestival.com. Archived from the original on 23 October 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- ^ McIntyre, Catherine (2014). "Influences". Visual Alchemy: The Fine Art of Digital Montage. Focal Press. p. 46. ISBN 9781135046149.

- ^ Cuthbertson, Debbie (17 January 2014). "Adelaide artist Emma Hack breathes new life into Florence Broadhurst archive". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ Sliff, Morgan (30 December 2016). "LA Artist Uses Nude Body Art to Say 'Sharks Are People Too'". The Inertia.

- ^ Marican, Shireen (3 February 2016). "The Pioneer: Michel Platnic, Baconesque and Blurring Boundaries". Art and Only - The Platform for Collectors. Archived from the original on 2020-11-17.

- ^ "Body Paint by Paul Roustan". Dodho Magazine. 1 January 2015.

- ^ "New Platform Romio, Painter Trina Merry, Violinist Charlie Siem And Opera Star Iestyn Davies Among Clients Featured In 360bespoke's Seasonal Media Report". Markets Insider (Press release). PR Newswire. 30 January 2018.

- ^ Raquel Laneri (3 May 2018). "Artist paints naked models with famous masterpieces". New York Post. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ^ Melania Hidalgo (2 May 2018). "An Art Fair Where the Pieces Come to Life". The Cut.

- ^ Zeveloff, Julie (2012-02-03). "Watch As The Amazing Artist Cecilia Paredes Disappears Into Wallpaper". Business Insider. Retrieved 2018-04-07.

- ^ "Sachin is this fan's match ticket". The Times of India. 31 January 2007. Archived from the original on 27 February 2010. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ^ "Illusion Magazine". illusionmagazine.co.uk. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ DeMello, Margo (2012). Faces Around the World: A Cultural Encyclopedia of the Human Face. ABC-CLIO. p. 106. ISBN 9781598846171.

- ^ DeMello (2012), p. 107–108.

- ^ "Painting on Tradition in Madagascar". PeaceCorps.gov. Retrieved 2023-07-05.

- ^ Emma Chambers. "Makeup And Lead Poisoning In The 18th Century". University College London. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ Mahar, William John (1999). Behind the Burnt Cork Mask: Early Blackface Minstrelsy and Antebellum American Popular Culture. University of Illinois Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-252-06696-0.

- ^ Sweet, Frank W. (2000). A History of the Minstrel Show. Boxes & Arrows. p. 25. ISBN 9780939479214.

- ^ Reinhartz, Adele, ed. (2012). Bible and Cinema: Fifty Key Films. Routledge. p. 197. ISBN 9781136183997.

- ^ Marchi, Regina M (2022). Day of the Dead in the USA: The Migration and Transformation of a Cultural Phenomenon (Second ed.). Rutgers University Press. p. 60. ISBN 9781978821651.

- ^ DeMello (2012), p. 109.

- ^ "Brigada de Fusileros Paracaidistas Mexicanos". taringa.net (in Spanish). 8 September 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ Metin Tolan - Geschüttelt, nicht gerührt, Piper Verlag

- ^ "Color Additive Status List". The Food and Drug Administration. December 2009. Archived from the original on February 23, 2010. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "Summary of Color Additives for Use in United States in Foods, Drugs, Cosmetics, and Medical Devices". The Food and Drug Administration. March 2007. Archived from the original on June 11, 2009. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "California Proposition 65 Update: Lead Limits for Cosmetic Products". Hong Kong Trade Development Council. 18 June 2009. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ Valenti, Lauren (9 September 2016). "The New "Body Marbling" Trend Is Must-See Stuff, People". Marie Claire.

- ^ Scott, Ellen (9 September 2016). "Body Marbling Is the New Festival Trend You're Going to Be Obsessed with". Metro.

- ^ Dowling, Amber. "Glitter boobs are a thing now, you've been warned". The Loop. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ "10 Reasons Why 'Glitter Boobs' Are Summer's Hottest Music Festival Trend". Maxim. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ Tierney, Allison. "People Can't Stop Taking Photos of Their Glittery Butts". Vice. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

External links

[edit]Body painting

View on GrokipediaHistory

Prehistoric and Ancient Origins

The earliest direct evidence of pigment processing potentially for body decoration dates to approximately 100,000 years ago at Blombos Cave in South Africa, where archaeological excavations uncovered ochre-processing kits including ground ochre mixed with charcoal and quartzite slabs used as grinding tools, indicating deliberate preparation of colored compounds suitable for application to skin or other surfaces.[8] This predates similar findings elsewhere and aligns with broader patterns of ochre use by early Homo sapiens for body modification, as ochre residues on tools and personal ornaments suggest symbolic or practical adornment rather than solely utilitarian purposes like hide processing.[9] In Paleolithic Europe, ochre pigments appear in Upper Paleolithic contexts around 40,000–10,000 years ago, with residues found in sites associated with mobile hunter-gatherer groups; for instance, red ochre chunks and processed hematite at caves like Lascaux in France imply transferrable use for body decoration, corroborated by ethnographic parallels where such pigments served non-permanent skin applications absent durable alternatives like textiles.[10] Neanderthals in Europe and western Asia also processed ochre as early as 250,000 years ago, with manganese dioxide additions for darker tones, pointing to convergent behavioral traits across hominin species driven by innate capacities for visual signaling rather than cultural diffusion.[11] Parallel evidence emerges in Asia, such as at Zhoukoudian Upper Cave in China (ca. 30,000–18,000 years ago), where red ochre was associated with personal ornaments like bone pendants and shell beads on human remains, suggesting body decoration integrated with burial practices and indicating independent regional development tied to environmental availability of iron-rich minerals and human cognitive universals for pigment-based expression.[12] In ancient Egypt, red ochre (hematite) was applied to mummified bodies from the Predynastic period onward (ca. 4000 BCE), as traces on skeletal remains and wrappings demonstrate ritualistic coloring to invoke vitality or protection, a practice extending to living individuals in ceremonial contexts based on pigment analyses of burial goods.[13] This continuity from prehistoric ochre use underscores body painting's persistence as a cross-cultural adaptation, with verifiable artifacts prioritizing empirical pigment sourcing over interpretive symbolism.[14]Indigenous and Traditional Practices

Australian Aboriginal peoples have employed body painting with ochre pigments, known as awelye in Central Desert regions, to encode Dreamtime narratives, mark rites of passage, and signify totemic affiliations during women's ceremonies that reinforce connections to ancestral lands and responsibilities.[15][16] These designs, applied to the chest, arms, and breasts using ground ochre mixed with ash or clay, serve communicative functions representing clan identities and ancestral beings, with ethnographic records indicating continuity in remote communities despite declines linked to modernization and reduced ceremonial frequency since European contact.[16][17] In Native North American tribes, body painting functioned practically for hunting camouflage and warfare intimidation, with pigments derived from clays, plants, and minerals applied in patterns to blend with environments or convey symbols of prowess and spiritual invocation prior to battles.[18] Archaeological and historical accounts from the 19th century document these uses among Plains Indians, where dark paints aided concealment and red ochre symbolized blood and vitality, enhancing group cohesion through shared ritual preparation.[19] Such applications, observed by artists like George Catlin in the 1830s, underscore causal roles in survival strategies beyond symbolic intent. Among East African Maasai warriors, red ochre (olkaria) mixed with animal fat coats the body and hair to denote status during initiations and ceremonies, providing empirical benefits including ultraviolet radiation blockage—due to iron oxide content offering sun protection—and mosquito deterrence, as substantiated by ethnographic studies and lab tests on ochre's repellent properties.[20][21] These practices, persisting in pastoralist lifestyles, prioritize functional adaptation to arid environments over purely ritualistic framing, with ochre sourcing tied to territorial claims and social hierarchy.[22]Modern and Western Evolution

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, European ethnographers' documentation of indigenous body decoration practices spurred a revival of interest in body painting within Western art circles, as these accounts highlighted non-Western aesthetic forms previously marginalized in colonial narratives.[23] This exposure influenced modernist painters, including Pablo Picasso, whose engagement with African sculptural and decorative traditions—encompassing scarification and painted motifs—contributed to the fragmentation and abstraction characteristic of Cubism beginning around 1907.[24][25] Such influences arose from curio collections in museums like Paris's Trocadéro, where artifacts arrived via colonial trade, prompting artists to reinterpret bodily adornment through lenses of primitivism and formal innovation rather than ritual context.[26] The 1960s counterculture in the United States and Europe accelerated body painting's transition toward expressive individualism, intertwining it with psychedelic experimentation, communal nudity, and rejection of conventional dress codes during events like San Francisco's Human Be-In in 1967.[27] Practitioners applied vibrant, swirling patterns to bare skin to evoke hallucinogenic visions, aligning with broader liberalization of nudity taboos amid the sexual revolution and anti-establishment ethos.[28] This period marked a causal shift from ethnographic curiosity to participatory art, as market-driven media coverage of hippie gatherings commodified the form for youth subcultures seeking sensory liberation. Pioneering works like Yves Klein's Anthropométries series, debuted in 1960 at Paris's Galerie Internationale d'Art Contemporain, exemplified early performance integration by directing nude female models—termed "living brushes"—to imprint International Klein Blue paint onto canvases during orchestrated events with live audiences and classical music.[29] Klein's method emphasized immateriality and bodily imprint over manual application, influencing the ensuing body art movement of the late 1960s and 1970s, where artists like those in the Viennese Actionists extended direct corporeal manipulation into provocative, endurance-based spectacles.[30] These developments reflected post-war existentialism and feminist critiques, though Klein's use of female bodies as tools drew later scrutiny for reinforcing gender dynamics in avant-garde practice.[31] By the 1980s, airbrush techniques proliferated in Western commercial contexts, enabling precise, photorealistic body painting for advertising and entertainment, as the tool's adoption in postmodern aesthetics allowed scalable production amid rising consumer individualism.[32] This era's market forces, including Hollywood effects and music video demands, professionalized body painting, shifting it from avant-garde rarity to viable freelance industry.[33]Post-2000, digital platforms facilitated global dissemination of body painting tutorials and imagery, hybridizing traditional motifs with contemporary designs and spurring commercial accessibility through at-home kits sold via e-commerce since the mid-2010s.[34] Internet-enabled sharing democratized the practice, with social media amplifying hybrid styles in festivals and protests, though this expansion often diluted ritual origins in favor of ephemeral, consumer-oriented expressions.[35]