Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Fluorescence

View on Wikipedia

Fluorescence is one of two kinds of photoluminescence, the emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation. When exposed to ultraviolet radiation, many substances will glow (fluoresce) with colored visible light. The color of the light emitted depends on the chemical composition of the substance. Fluorescent materials generally cease to glow nearly immediately when the radiation source stops. This distinguishes them from the other type of light emission, phosphorescence. Phosphorescent materials continue to emit light for some time after the radiation stops. This difference in duration is a result of quantum spin effects.

Fluorescence occurs when a photon from incoming radiation is absorbed by a molecule, exciting it to a higher energy level, followed by the emission of light as the molecule returns to a lower energy state. The emitted light may have a longer wavelength and, therefore, a lower photon energy than the absorbed radiation. For example, the absorbed radiation could be in the ultraviolet region of the electromagnetic spectrum (invisible to the human eye), while the emitted light is in the visible region. This gives the fluorescent substance a distinct color, best seen when exposed to UV light, making it appear to glow in the dark. However, any light with a shorter wavelength may cause a material to fluoresce at a longer wavelength. Fluorescent materials may also be excited by certain wavelengths of visible light, which can mask the glow, yet their colors may appear bright and intensified. Other fluorescent materials emit their light in the infrared or even the ultraviolet regions of the spectrum.

Fluorescence has many practical applications, including mineralogy, gemology, medicine, chemical sensors (fluorescence spectroscopy), fluorescent labelling, dyes, biological detectors, cosmic-ray detection, vacuum fluorescent displays, and cathode-ray tubes. Its most common everyday application is in (gas-discharge) fluorescent lamps and LED lamps, where fluorescent coatings convert UV or blue light into longer wavelengths, resulting in white light, which can appear indistinguishable from that of the traditional but energy-inefficient incandescent lamp.

Fluorescence also occurs frequently in nature, appearing in some minerals and many biological forms across all kingdoms of life. The latter is often referred to as biofluorescence, indicating that the fluorophore is part of or derived from a living organism (rather than an inorganic dye or stain). However, since fluorescence results from a specific chemical property that can often be synthesized artificially, it is generally sufficient to describe the substance itself as fluorescent.

History

[edit]

Fluorescence was observed long before it was named and understood.[1] An early observation of fluorescence was known to the Aztecs[1] and described in 1560 by Bernardino de Sahagún and in 1565 by Nicolás Monardes in the infusion known as lignum nephriticum (Latin for "kidney wood"). It was derived from the wood of two tree species, Pterocarpus indicus and Eysenhardtia polystachya.[2][3][4] The chemical compound responsible for this fluorescence is matlaline, which is the oxidation product of one of the flavonoids found in this wood.[2]

In 1819, E.D. Clarke[5] and in 1822 René Just Haüy [6] described some varieties of fluorites that had a different color depending on whether the light was reflected or (apparently) transmitted. Haüy incorrectly viewed the effect as light scattering similar to opalescence.[1]: Fig.5 In 1833 Sir David Brewster described a similar effect in chlorophyll which he also considered a form of opalescence.[7] Sir John Herschel studied quinine in 1845[8][9] and came to a different incorrect conclusion.[1]

In 1842, A.E. Becquerel observed that calcium sulfide emits light after being exposed to solar ultraviolet, making him the first to state that the emitted light is of longer wavelength than the incident light. While his observation of photoluminescence was similar to that described 10 years later by Stokes, who observed a fluorescence of a solution of quinine, the phenomenon that Becquerel described with calcium sulfide is now called phosphorescence.[1]

In his 1852 paper on the "Refrangibility" (wavelength change) of light, George Gabriel Stokes described the ability of fluorspar, uranium glass and many other substances to change invisible light beyond the violet end of the visible spectrum into visible light. He named this phenomenon fluorescence[1]

- "I am almost inclined to coin a word, and call the appearance fluorescence, from fluor-spar [i.e., fluorite], as the analogous term opalescence is derived from the name of a mineral."[10](p 479, footnote)

Neither Becquerel nor Stokes understood one key aspect of photoluminescence: the critical difference from incandescence, the emission of light by heated material. To distinguish it from incandescence, in the late 1800s, Gustav Wiedemann proposed the term luminescence to designate any emission of light more intense than expected from the source's temperature.[1]

Advances in spectroscopy and quantum electronics between the 1950s and 1970s provided a way to distinguish between the three different mechanisms that produce the light, as well as narrowing down the typical timescales those mechanisms take to decay after absorption. In modern science, this distinction became important because some items, such as lasers, required the fastest decay times, which typically occur in the nanosecond (billionth of a second) range. In physics, this first mechanism was termed "fluorescence" or "singlet emission", and is common in many laser mediums such as ruby. Other fluorescent materials were discovered to have much longer decay times, because some of the atoms would change their spin to a triplet state, thus would glow brightly with fluorescence under excitation but produce a dimmer afterglow for a short time after the excitation was removed, which became labeled "phosphorescence" or "triplet phosphorescence". The typical decay times ranged from a few microseconds to one second, which are still fast enough by human-eye standards to be colloquially referred to as fluorescent. Common examples include fluorescent lamps, organic dyes, and even fluorspar. Longer emitters, commonly referred to as glow-in-the-dark substances, ranged from one second to many hours, and this mechanism was called persistent phosphorescence or persistent luminescence, to distinguish it from the other two mechanisms.[11]: 1–25

Physical principles

[edit]Mechanism

[edit]

Fluorescence occurs when an excited molecule, atom, or nanostructure, relaxes to a lower energy state (usually the ground state) through emission of a photon without a change in electron spin. When the initial and final states have different multiplicity (spin), the phenomenon is termed phosphorescence.[12]

When a molecule in its ground state (called S0) is photoexcited it may end up in any one of a number of excited states (S1, S2, S3,...). These higher excited states are different vibrational levels, populated in proportion to their overlap with the ground state according to the Franck-Condon principle.[13]: 31 These vibrational excited states typically decay rapidly by to S1, followed by radiative transition to the ground state or to vibrational states close to the ground state. This transition is called fluorescence. All of these states are singlet states.[14]: 225

A different pathway for deexcitation is intersystem crossing from the S1 to a triplet state T1. Decay from T1 to S0 is typically slower and less intense and is called phosphorescence.[14]: 225

Absorption of a photon of energy results in an excited state of the same multiplicity (spin) of the ground state, usually a singlet (Sn with n > 0). In solution, states with n > 1 relax rapidly to the lowest vibrational level of the first excited state (S1) by transferring energy to the solvent molecules through non-radiative processes, including internal conversion followed by vibrational relaxation, in which the energy is dissipated as heat. Thus the fluorescence energy is typically less than the photoexcitation energy.[13]: 38

The excited state S1 can relax by other mechanisms that do not involve the emission of light. These processes, called non-radiative processes, compete with fluorescence emission and decrease its efficiency.[13] Examples include internal conversion, intersystem crossing to the triplet state, and energy transfer to another molecule. An example of energy transfer is Förster resonance energy transfer. Relaxation from an excited state can also occur through collisional quenching, a process where a molecule (the quencher) collides with the fluorescent molecule during its excited state lifetime. Molecular oxygen (O2) is an extremely efficient quencher of fluorescence because of its unusual triplet ground state.

Quantum yield

[edit]The fluorescence quantum yield gives the efficiency of the fluorescence process. It is defined as the ratio of the number of photons emitted to the number of photons absorbed.[15](p 10)[13]

The maximum possible fluorescence quantum yield is 1.0 (100%); each photon absorbed results in a photon emitted. Compounds with quantum yields of 0.10 are still considered quite fluorescent. Another way to define the quantum yield of fluorescence is by the rate of excited state decay:

where is the rate constant of spontaneous emission of radiation and

is the sum of all rates of excited state decay. Other rates of excited state decay are caused by mechanisms other than photon emission and are, therefore, often called "non-radiative rates", which can include:

- dynamic collisional quenching

- near-field dipole–dipole interaction (or resonance energy transfer)

- internal conversion

- intersystem crossing

Thus, if the rate of any pathway changes, both the excited state lifetime and the fluorescence quantum yield will be affected.

Fluorescence quantum yields are measured by comparison to a standard.[16] The quinine salt quinine sulfate in a sulfuric acid solution was regarded as the most common fluorescence standard,[17] however, a recent study revealed that the fluorescence quantum yield of this solution is strongly affected by the temperature, and should no longer be used as the standard solution. The quinine in 0.1 M perchloric acid (Φ = 0.60) shows no temperature dependence up to 45 °C, therefore it can be considered as a reliable standard solution.[18]

Lifetime

[edit]

The fluorescence lifetime refers to the average time the molecule stays in its excited state before emitting a photon. Fluorescence typically follows first-order kinetics:

where is the concentration of excited state molecules at time , is the initial concentration and is the decay rate or the inverse of the fluorescence lifetime. This is an instance of exponential decay. Various radiative and non-radiative processes can de-populate the excited state. In such case the total decay rate is the sum over all rates:

where is the total decay rate, the radiative decay rate and the non-radiative decay rate. It is similar to a first-order chemical reaction in which the first-order rate constant is the sum of all of the rates (a parallel kinetic model). If the rate of spontaneous emission, or any of the other rates are fast, the lifetime is short. For commonly used fluorescent compounds, typical excited state decay times for photon emissions with energies from the UV to near infrared are within the range of 0.5 to 20 nanoseconds. The fluorescence lifetime is an important parameter for practical applications of fluorescence such as fluorescence resonance energy transfer and fluorescence-lifetime imaging microscopy.

Jablonski diagram

[edit]The Jablonski diagram describes most of the relaxation mechanisms for excited state molecules. The diagram alongside shows how fluorescence occurs due to the relaxation of certain excited electrons of a molecule.[19]

Fluorescence anisotropy

[edit]Fluorophores are more likely to be excited by photons if the transition moment of the fluorophore is parallel to the electric vector of the photon.[15](pp 12–13) The polarization of the emitted light will also depend on the transition moment. The transition moment is dependent on the physical orientation of the fluorophore molecule. For fluorophores in solution, the intensity and polarization of the emitted light is dependent on rotational diffusion. Therefore, anisotropy measurements can be used to investigate how freely a fluorescent molecule moves in a particular environment.

Fluorescence anisotropy can be defined quantitatively as

where is the emitted intensity parallel to the polarization of the excitation light and is the emitted intensity perpendicular to the polarization of the excitation light.[13]

Anisotropy is independent of the intensity of the absorbed or emitted light, it is the property of the light, so photobleaching of the dye will not affect the anisotropy value as long as the signal is detectable.

Fluorescence

[edit]

Strongly fluorescent pigments often have an unusual appearance which is often described colloquially as a "neon color" (originally "day-glo" in the late 1960s, early 1970s). This phenomenon was termed "Farbenglut" by Hermann von Helmholtz and "fluorence" by Ralph M. Evans. It is generally thought to be related to the high brightness of the color relative to what it would be as a component of white. Fluorescence shifts energy in the incident illumination from shorter wavelengths to longer (such as blue to yellow) and thus can make the fluorescent color appear brighter (more saturated) than it could possibly be by reflection alone.[20]

Rules

[edit]There are several general rules that deal with fluorescence. Each of the following rules have exceptions but they are useful guidelines for understanding fluorescence (these rules do not necessarily apply to two-photon absorption).

Kasha's rule

[edit]Kasha's rule states that the luminesce (fluorescence or phosphorescence) of a molecule will be emitted only from the lowest excited state of its given multiplicity.[21] Vavilov's rule (a logical extension of Kasha's rule thusly called Kasha–Vavilov rule) dictates that the quantum yield of luminescence is independent of the wavelength of exciting radiation and is proportional to the absorbance of the excited wavelength.[22] Kasha's rule does not always apply and is violated by simple molecules, such an example is azulene.[23] A somewhat more reliable statement, although still with exceptions, would be that the fluorescence spectrum shows very little dependence on the wavelength of exciting radiation.[24]

Mirror image rule

[edit]

For many fluorophores the absorption spectrum is a mirror image of the emission spectrum.[15](pp 6–8) This is known as the mirror image rule and is related to the Franck–Condon principle which states that electronic transitions are vertical, that is energy changes without distance changing as can be represented with a vertical line in Jablonski diagram. This means the nucleus does not move and the vibration levels of the excited state resemble the vibration levels of the ground state.

Stokes shift

[edit]In general, emitted fluorescence light has a longer wavelength and lower energy than the absorbed light.[15](pp 6–7) This phenomenon, known as Stokes shift, is due to energy loss between the time a photon is absorbed and when a new one is emitted. The causes and magnitude of Stokes shift can be complex and are dependent on the fluorophore and its environment. However, there are some common causes. It is frequently due to non-radiative decay to the lowest vibrational energy level of the excited state. Another factor is that the emission of fluorescence frequently leaves a fluorophore in a higher vibrational level of the ground state.

In nature

[edit]

There are many natural compounds that exhibit fluorescence, and they have a number of applications. Some deep-sea animals, such as the greeneye, have fluorescent structures.

Compared to bioluminescence and biophosphorescence

[edit]Fluorescence

[edit]Fluorescence is the phenomenon of absorption of electromagnetic radiation, typically from ultraviolet or visible light, by a molecule and the subsequent emission of a photon of a lower energy (smaller frequency, longer wavelength). This causes the light that is emitted to be a different color than the light that is absorbed. Stimulating light excites an electron to an excited state. When the molecule returns to the ground state, it releases a photon, which is the fluorescent emission. The excited state lifetime is short, so emission of light is typically only observable when the absorbing light is on. Fluorescence can be of any wavelength but is often more significant when emitted photons are in the visible spectrum. When it occurs in a living organism, it is sometimes called biofluorescence. Fluorescence should not be confused with bioluminescence and biophosphorescence.[25] Pumpkin toadlets that live in the Brazilian Atlantic forest are fluorescent.[26]

Bioluminescence

[edit]Bioluminescence differs from fluorescence in that it is the natural production of light by chemical reactions within an organism, whereas fluorescence is the absorption and reemission of light from the environment.[25] Fireflies and anglerfish are two examples of bioluminescent organisms.[27] To add to the potential confusion, some organisms are both bioluminescent and fluorescent, like the sea pansy Renilla reniformis, where bioluminescence serves as the light source for fluorescence.[28]

Phosphorescence

[edit]Phosphorescence is similar to fluorescence in its requirement of light wavelengths as a provider of excitation energy. The difference here lies in the relative stability of the energized electron. Unlike with fluorescence, in phosphorescence the electron retains stability, emitting light that continues to "glow in the dark" even after the stimulating light source has been removed.[25] For example, glow-in-the-dark stickers are phosphorescent, but there are no truly biophosphorescent animals known.[29]

Mechanisms

[edit]Epidermal chromatophores

[edit]Pigment cells that exhibit fluorescence are called fluorescent chromatophores, and function somatically similar to regular chromatophores. These cells are dendritic, and contain pigments called fluorosomes. These pigments contain fluorescent proteins which are activated by K+ (potassium) ions, and it is their movement, aggregation, and dispersion within the fluorescent chromatophore that cause directed fluorescence patterning.[30][31] Fluorescent cells are innervated the same as other chromatophores, like melanophores, pigment cells that contain melanin. Short term fluorescent patterning and signaling is controlled by the nervous system.[30] Fluorescent chromatophores can be found in the skin (e.g. in fish) just below the epidermis, amongst other chromatophores.

Epidermal fluorescent cells in fish also respond to hormonal stimuli by the α–MSH and MCH hormones much the same as melanophores. This suggests that fluorescent cells may have color changes throughout the day that coincide with their circadian rhythm.[32] Fish may also be sensitive to cortisol induced stress responses to environmental stimuli, such as interaction with a predator or engaging in a mating ritual.[30]

Phylogenetics

[edit]Evolutionary origins

[edit]The incidence of fluorescence across the tree of life is widespread, and has been studied most extensively in cnidarians and fish. The phenomenon appears to have evolved multiple times in multiple taxa such as in the anguilliformes (eels), gobioidei (gobies and cardinalfishes), and tetradontiformes (triggerfishes), along with the other taxa discussed later in the article. Fluorescence is highly genotypically and phenotypically variable even within ecosystems, in regards to the wavelengths emitted, the patterns displayed, and the intensity of the fluorescence. Generally, the species relying upon camouflage exhibit the greatest diversity in fluorescence, likely because camouflage may be one of the uses of fluorescence.[33]

It is suspected by some scientists that GFPs and GFP-like proteins began as electron donors activated by light. These electrons were then used for reactions requiring light energy. Functions of fluorescent proteins, such as protection from the sun, conversion of light into different wavelengths, or for signaling are thought to have evolved secondarily.[34]

Adaptive functions

[edit]Currently, relatively little is known about the functional significance of fluorescence and fluorescent proteins.[34] However, it is suspected that fluorescence may serve important functions in signaling and communication, mating, lures, camouflage, UV protection and antioxidation, photoacclimation, dinoflagellate regulation, and in coral health.[35]

Aquatic

[edit]Water absorbs light of long wavelengths, so less light from these wavelengths reflects back to reach the eye. Therefore, warm colors from the visual light spectrum appear less vibrant at increasing depths. Water scatters light of shorter wavelengths above violet, meaning cooler colors dominate the visual field in the photic zone. Light intensity decreases 10 fold with every 75 m of depth, so at depths of 75 m, light is 10% as intense as it is on the surface, and is only 1% as intense at 150 m as it is on the surface. Because the water filters out the wavelengths and intensity of water reaching certain depths, different proteins, because of the wavelengths and intensities of light they are capable of absorbing, are better suited to different depths. Theoretically, some fish eyes can detect light as deep as 1000 m. At these depths of the aphotic zone, the only sources of light are organisms themselves, giving off light through chemical reactions in a process called bioluminescence.

Fluorescence is simply defined as the absorption of electromagnetic radiation at one wavelength and its reemission at another, lower energy wavelength.[33] Thus any type of fluorescence depends on the presence of external sources of light. Biologically functional fluorescence is found in the photic zone, where there is not only enough light to cause fluorescence, but enough light for other organisms to detect it.[36] The visual field in the photic zone is naturally blue, so colors of fluorescence can be detected as bright reds, oranges, yellows, and greens. Green is the most commonly found color in the marine spectrum, yellow the second most, orange the third, and red is the rarest. Fluorescence can occur in organisms in the aphotic zone as a byproduct of that same organism's bioluminescence. Some fluorescence in the aphotic zone is merely a byproduct of the organism's tissue biochemistry and does not have a functional purpose. However, some cases of functional and adaptive significance of fluorescence in the aphotic zone of the deep ocean is an active area of research.[37]

Photic zone

[edit]Fish

[edit]

Bony fishes living in shallow water generally have good color vision due to their living in a colorful environment. Thus, in shallow-water fishes, red, orange, and green fluorescence most likely serves as a means of communication with conspecifics, especially given the great phenotypic variance of the phenomenon.[33]

Many fish that exhibit fluorescence, such as sharks, lizardfish, scorpionfish, wrasses, and flatfishes, also possess yellow intraocular filters.[38] Yellow intraocular filters in the lenses and cornea of certain fishes function as long-pass filters. These filters enable the species to visualize and potentially exploit fluorescence, in order to enhance visual contrast and patterns that are unseen to other fishes and predators that lack this visual specialization.[33] Fish that possess the necessary yellow intraocular filters for visualizing fluorescence potentially exploit a light signal from members of it. Fluorescent patterning was especially prominent in cryptically patterned fishes possessing complex camouflage. Many of these lineages also possess yellow long-pass intraocular filters that could enable visualization of such patterns.[38]

Another adaptive use of fluorescence is to generate orange and red light from the ambient blue light of the photic zone to aid vision. Red light can only be seen across short distances due to attenuation of red light wavelengths by water.[39] Many fish species that fluoresce are small, group-living, or benthic/aphotic, and have conspicuous patterning. This patterning is caused by fluorescent tissue and is visible to other members of the species, however the patterning is invisible at other visual spectra. These intraspecific fluorescent patterns also coincide with intra-species signaling. The patterns present in ocular rings to indicate directionality of an individual's gaze, and along fins to indicate directionality of an individual's movement.[39] Current research suspects that this red fluorescence is used for private communication between members of the same species.[30][33][39] Due to the prominence of blue light at ocean depths, red light and light of longer wavelengths are muddled, and many predatory reef fish have little to no sensitivity for light at these wavelengths. Fish such as the fairy wrasse that have developed visual sensitivity to longer wavelengths are able to display red fluorescent signals that give a high contrast to the blue environment and are conspicuous to conspecifics in short ranges, yet are relatively invisible to other common fish that have reduced sensitivities to long wavelengths. Thus, fluorescence can be used as adaptive signaling and intra-species communication in reef fish.[39][40]

Additionally, it is suggested that fluorescent tissues that surround an organism's eyes are used to convert blue light from the photic zone or green bioluminescence in the aphotic zone into red light to aid vision.[39]

Sharks

[edit]A new fluorophore was described in two species of sharks, wherein it was due to an undescribed group of brominated tryptophane-kynurenine small molecule metabolites.[41]

Coral

[edit]Fluorescence serves a wide variety of functions in coral. Fluorescent proteins in corals may contribute to photosynthesis by converting otherwise unusable wavelengths of light into ones for which the coral's symbiotic algae are able to conduct photosynthesis.[42] Also, the proteins may fluctuate in number as more or less light becomes available as a means of photoacclimation.[43] Similarly, these fluorescent proteins may possess antioxidant capacities to eliminate oxygen radicals produced by photosynthesis.[44] Finally, through modulating photosynthesis, the fluorescent proteins may also serve as a means of regulating the activity of the coral's photosynthetic algal symbionts.[45]

Cephalopods

[edit]Alloteuthis subulata and Loligo vulgaris, two types of nearly transparent squid, have fluorescent spots above their eyes. These spots reflect incident light, which may serve as a means of camouflage, but also for signaling to other squids for schooling purposes.[46]

Jellyfish

[edit]

Another, well-studied example of fluorescence in the ocean is the hydrozoan Aequorea victoria. This jellyfish lives in the photic zone off the west coast of North America and was identified as a carrier of green fluorescent protein (GFP) by Osamu Shimomura. The gene for these green fluorescent proteins has been isolated and is scientifically significant because it is widely used in genetic studies to indicate the expression of other genes.[47]

Mantis shrimp

[edit]Several species of mantis shrimp, which are stomatopod crustaceans, including Lysiosquillina glabriuscula, have yellow fluorescent markings along their antennal scales and carapace (shell) that males present during threat displays to predators and other males. The display involves raising the head and thorax, spreading the striking appendages and other maxillipeds, and extending the prominent, oval antennal scales laterally, which makes the animal appear larger and accentuates its yellow fluorescent markings. Furthermore, as depth increases, mantis shrimp fluorescence accounts for a greater part of the visible light available. During mating rituals, mantis shrimp actively fluoresce, and the wavelength of this fluorescence matches the wavelengths detected by their eye pigments.[48]

Aphotic zone

[edit]Siphonophores

[edit]Siphonophorae is an order of marine animals from the phylum Hydrozoa that consist of a specialized medusoid and polyp zooid. Some siphonophores, including the genus Erenna that live in the aphotic zone between depths of 1600 m and 2300 m, exhibit yellow to red fluorescence in the photophores of their tentacle-like tentilla. This fluorescence occurs as a by-product of bioluminescence from these same photophores. The siphonophores exhibit the fluorescence in a flicking pattern that is used as a lure to attract prey.[49]

Dragonfish

[edit]The predatory deep-sea dragonfish Malacosteus niger, the closely related genus Aristostomias and the species Pachystomias microdon use fluorescent red accessory pigments to convert the blue light emitted from their own bioluminescence to red light from suborbital photophores. This red luminescence is invisible to other animals, which allows these dragonfish extra light at dark ocean depths without attracting or signaling predators.[50]

Terrestrial

[edit]Amphibians

[edit]

Fluorescence is widespread among amphibians and has been documented in several families of frogs, salamanders and caecilians, but the extent of it varies greatly.[51]

The polka-dot tree frog (Hypsiboas punctatus), widely found in South America, was unintentionally discovered to be the first fluorescent amphibian in 2017. The fluorescence was traced to a new compound found in the lymph and skin glands.[52] The main fluorescent compound is Hyloin-L1 and it gives a blue-green glow when exposed to violet or ultraviolet light. The scientists behind the discovery suggested that the fluorescence can be used for communication. They speculated that fluorescence possibly is relatively widespread among frogs.[53] Only a few months later, fluorescence was discovered in the closely related Hypsiboas atlanticus. Because it is linked to secretions from skin glands, they can also leave fluorescent markings on surfaces where they have been.[54]

In 2019, two other frogs, the tiny pumpkin toadlet (Brachycephalus ephippium) and red pumpkin toadlet (B. pitanga) of southeastern Brazil, were found to have naturally fluorescent skeletons, which are visible through their skin when exposed to ultraviolet light.[55][56] It was initially speculated that the fluorescence supplemented their already aposematic colours (they are toxic) or that it was related to mate choice (species recognition or determining fitness of a potential partner),[55] but later studies indicate that the former explanation is unlikely, as predation attempts on the toadlets appear to be unaffected by the presence/absence of fluorescence.[57]

In 2020 it was confirmed that green or yellow fluorescence is widespread not only in adult frogs that are exposed to blue or ultraviolet light, but also among tadpoles, salamanders and caecilians. The extent varies greatly depending on species; in some it is highly distinct and in others it is barely noticeable. It can be based on their skin pigmentation, their mucus or their bones.[51]

Butterflies

[edit]Swallowtail (Papilio) butterflies have complex systems for emitting fluorescent light. Their wings contain pigment-infused crystals that provide directed fluorescent light. These crystals function to produce fluorescent light best when they absorb radiance from sky-blue light (wavelength about 420 nm). The wavelengths of light that the butterflies see the best correspond to the absorbance of the crystals in the butterfly's wings. This likely functions to enhance the capacity for signaling.[58]

Parrots

[edit]Parrots have fluorescent plumage that may be used in mate signaling. A study using mate-choice experiments on budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulates) found compelling support for fluorescent sexual signaling, with both males and females significantly preferring birds with the fluorescent experimental stimulus. This study suggests that the fluorescent plumage of parrots is not simply a by-product of pigmentation, but instead an adapted sexual signal. Considering the intricacies of the pathways that produce fluorescent pigments, there may be significant costs involved. Therefore, individuals exhibiting strong fluorescence may be honest indicators of high individual quality, since they can deal with the associated costs.[59]

Arachnids

[edit]

Spiders fluoresce under UV light and possess a huge diversity of fluorophores. Andrews, Reed, & Masta noted that spiders are the only known group in which fluorescence is "taxonomically widespread, variably expressed, evolutionarily labile, and probably under selection and potentially of ecological importance for intraspecific and interspecific signaling".[60] They showed that fluorescence evolved multiple times across spider taxa, with novel fluorophores evolving during spider diversification.

In some spiders, ultraviolet cues are important for predator–prey interactions, intraspecific communication, and camouflage-matching with fluorescent flowers. Differing ecological contexts could favor inhibition or enhancement of fluorescence expression, depending upon whether fluorescence helps spiders be cryptic or makes them more conspicuous to predators. Therefore, natural selection could be acting on expression of fluorescence across spider species.[60]

Scorpions are also fluorescent, in their case due to the presence of beta-carboline in their cuticles.[61]

Platypus

[edit]In 2020 fluorescence was reported for several platypus specimens.[62]

Plants

[edit]Many plants are fluorescent due to the presence of chlorophyll, which is probably the most widely distributed fluorescent molecule, producing red emission under a range of excitation wavelengths.[63] This attribute of chlorophyll is commonly used by ecologists to measure photosynthetic efficiency.[64]

The Mirabilis jalapa flower contains violet, fluorescent betacyanins and yellow, fluorescent betaxanthins. Under white light, parts of the flower containing only betaxanthins appear yellow, but in areas where both betaxanthins and betacyanins are present, the visible fluorescence of the flower is faded due to internal light-filtering mechanisms. Fluorescence was previously suggested to play a role in pollinator attraction, however, it was later found that the visual signal by fluorescence is negligible compared to the visual signal of light reflected by the flower.[65]

Abiotic

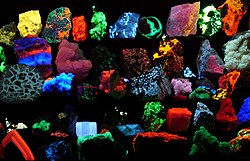

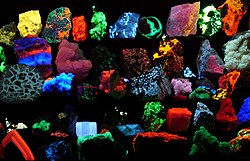

[edit]Gemology, mineralogy and geology

[edit]

In addition to the eponymous fluorspar,[66] many gemstones and minerals may have a distinctive fluorescence or may fluoresce differently under short-wave ultraviolet, long-wave ultraviolet, visible light, or X-rays.

Many types of calcite and amber will fluoresce under shortwave UV, longwave UV and visible light. Rubies, emeralds, and diamonds exhibit red fluorescence under long-wave UV, blue and sometimes green light; diamonds also emit light under X-ray radiation.

Fluorescence in minerals is caused by a wide range of activators. In some cases, the concentration of the activator must be restricted to below a certain level, to prevent quenching of the fluorescent emission. Furthermore, the mineral must be free of impurities such as iron or copper, to prevent quenching of possible fluorescence. Divalent manganese, in concentrations of up to several percent, is responsible for the red or orange fluorescence of calcite, the green fluorescence of willemite, the yellow fluorescence of esperite, and the orange fluorescence of wollastonite and clinohedrite. Hexavalent uranium, in the form of the uranyl cation (UO2+

2), fluoresces at all concentrations in a yellow green, and is the cause of fluorescence of minerals such as autunite or andersonite, and, at low concentration, is the cause of the fluorescence of such materials as some samples of hyalite opal. Trivalent chromium at low concentration is the source of the red fluorescence of ruby. Divalent europium is the source of the blue fluorescence, when seen in the mineral fluorite. Trivalent lanthanides such as terbium and dysprosium are the principal activators of the creamy yellow fluorescence exhibited by the yttrofluorite variety of the mineral fluorite, and contribute to the orange fluorescence of zircon. Powellite (calcium molybdate) and scheelite (calcium tungstate) fluoresce intrinsically in yellow and blue, respectively. When present together in solid solution, energy is transferred from the higher-energy tungsten to the lower-energy molybdenum, such that fairly low levels of molybdenum are sufficient to cause a yellow emission for scheelite, instead of blue. Low-iron sphalerite (zinc sulfide), fluoresces and phosphoresces in a range of colors, influenced by the presence of various trace impurities.

Crude oil (petroleum) fluoresces in a range of colors, from dull-brown for heavy oils and tars through to bright-yellowish and bluish-white for very light oils and condensates. This phenomenon is used in oil exploration drilling to identify very small amounts of oil in drill cuttings and core samples.

Humic acids and fulvic acids produced by the degradation of organic matter in soils (humus) may also fluoresce because of the presence of aromatic cycles in their complex molecular structures.[67] Humic substances dissolved in groundwater can be detected and characterized by spectrofluorimetry.[68] [69] [70]

Organic liquids

[edit]

Organic (carbon based) solutions such anthracene or stilbene, dissolved in benzene or toluene, fluoresce with ultraviolet or gamma ray irradiation. The decay times of this fluorescence are on the order of nanoseconds, since the duration of the light depends on the lifetime of the excited states of the fluorescent material, in this case anthracene or stilbene.[72]

Scintillation is defined a flash of light produced in a transparent material by the passage of a particle (an electron, an alpha particle, an ion, or a high-energy photon). Stilbene and derivatives are used in scintillation counters to detect such particles. Stilbene is also one of the gain mediums used in dye lasers.

Atmosphere

[edit]Fluorescence is observed in the atmosphere when the air is under energetic electron bombardment. In cases such as the natural aurora, high-altitude nuclear explosions, and rocket-borne electron gun experiments, the molecules and ions formed have a fluorescent response to light.[73]

Common materials that fluoresce

[edit]- Vitamin B2 fluoresces green, with an emission centered ~525 nm.

- Tonic water fluoresces blue due to the presence of quinine.

- Highlighter ink is often fluorescent due to the presence of pyranine.

- Banknotes, postage stamps and credit cards often have fluorescent security features.

In novel technology

[edit]In August 2020 researchers reported the creation of the brightest fluorescent solid optical materials so far by enabling the transfer of properties of highly fluorescent dyes via spatial and electronic isolation of the dyes by mixing cationic dyes with anion-binding cyanostar macrocycles. According to a co-author these materials may have applications in areas such as solar energy harvesting, bioimaging, and lasers.[74][75][76][77]

Applications

[edit]Lighting

[edit]

The common fluorescent lamp relies on fluorescence. Inside the glass tube is a partial vacuum and a small amount of mercury. An electric discharge in the tube causes the mercury atoms to emit mostly ultraviolet light. The tube is lined with a coating of a fluorescent material, called the phosphor, which absorbs ultraviolet light and re-emits visible light. Fluorescent lighting is more energy-efficient than incandescent lighting elements. However, the uneven spectrum of traditional fluorescent lamps may cause certain colors to appear different from when illuminated by incandescent light or daylight. The mercury vapor emission spectrum is dominated by a short-wave UV line at 254 nm (which provides most of the energy to the phosphors), accompanied by visible light emission at 436 nm (blue), 546 nm (green) and 579 nm (yellow-orange). These three lines can be observed superimposed on the white continuum using a hand spectroscope, for light emitted by the usual white fluorescent tubes. These same visible lines, accompanied by the emission lines of trivalent europium and trivalent terbium, and further accompanied by the emission continuum of divalent europium in the blue region, comprise the more discontinuous light emission of the modern trichromatic phosphor systems used in many compact fluorescent lamp and traditional lamps where better color rendition is a goal.[78]

Fluorescent lights were first available to the public at the 1939 New York World's Fair. Improvements since then have largely been better phosphors, longer life, and more consistent internal discharge, and easier-to-use shapes (such as compact fluorescent lamps). Some high-intensity discharge (HID) lamps couple their even-greater electrical efficiency with phosphor enhancement for better color rendition.[79]

White light-emitting diodes (LEDs) became available in the mid-1990s as LED lamps, in which blue light emitted from the semiconductor strikes phosphors deposited on the tiny chip. The combination of the blue light that continues through the phosphor and the green to red fluorescence from the phosphors produces a net emission of white light.[80]

Glow sticks sometimes utilize fluorescent materials to absorb light from the chemiluminescent reaction and emit light of a different color.[78]

Analytical chemistry

[edit]Many analytical procedures involve the use of a fluorometer, usually with a single exciting wavelength and single detection wavelength. Because of the sensitivity that the method affords, fluorescent molecule concentrations as low as 1 part per trillion can be measured.[81]

Fluorescence in several wavelengths can be detected by an array detector, to detect compounds from HPLC flow. Also, TLC plates can be visualized if the compounds or a coloring reagent is fluorescent. Fluorescence is most effective when there is a larger ratio of atoms at lower energy levels in a Boltzmann distribution. There is, then, a higher probability of excitement and release of photons by lower-energy atoms, making analysis more efficient.

Spectroscopy

[edit]Usually the setup of a fluorescence assay involves a light source, which may emit many different wavelengths of light. In general, a single wavelength is required for proper analysis, so, in order to selectively filter the light, it is passed through an excitation monochromator, and then that chosen wavelength is passed through the sample cell. After absorption and re-emission of the energy, many wavelengths may emerge due to Stokes shift and various electron transitions. To separate and analyze them, the fluorescent radiation is passed through an emission monochromator, and observed selectively by a detector.[82]

Lasers

[edit]

Lasers most often use the fluorescence of certain materials as their active media, such as the red glow produced by a ruby (chromium sapphire), the infrared of titanium sapphire, or the unlimited range of colors produced by organic dyes. These materials normally fluoresce through a process called spontaneous emission, in which the light is emitted in all directions and often at many discrete spectral lines all at once. In many lasers, the fluorescent medium is "pumped" by exposing it to an intense light source, creating a population inversion, meaning that more of its atoms become in an excited state (high energy) rather than at ground state (low energy). When this occurs, the spontaneous fluorescence can then induce the other atoms to emit their photons in the same direction and at the same wavelength, creating stimulated emission. When a portion of the spontaneous fluorescence is trapped between two mirrors, nearly all of the medium's fluorescence can be stimulated to emit along the same line, producing a laser beam.[83]

Biochemistry and medicine

[edit]

Fluorescence in the life sciences is used generally as a non-destructive way of tracking or analysis of biological molecules by means of the fluorescent emission at a specific frequency where there is no background from the excitation light, as relatively few cellular components are naturally fluorescent (called intrinsic or autofluorescence). In fact, a protein or other component can be "labelled" with an extrinsic fluorophore, a fluorescent dye that can be a small molecule, protein, or quantum dot, finding a large use in many biological applications.[15](p xxvi)

The quantification of a dye is done with a spectrofluorometer and finds additional applications in:

Microscopy

[edit]- When scanning the fluorescence intensity across a plane one has fluorescence microscopy of tissues, cells, or subcellular structures, which is accomplished by labeling an antibody with a fluorophore and allowing the antibody to find its target antigen within the sample. Labelling multiple antibodies with different fluorophores allows visualization of multiple targets within a single image (multiple channels). DNA microarrays are a variant of this.

- Immunology: An antibody is first prepared by having a fluorescent chemical group attached, and the sites (e.g., on a microscopic specimen) where the antibody has bound can be seen, and even quantified, by the fluorescence.

- FLIM (Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy) can be used to detect certain bio-molecular interactions that manifest themselves by influencing fluorescence lifetimes.

- Cell and molecular biology: detection of colocalization using fluorescence-labelled antibodies for selective detection of the antigens of interest using specialized software such as ImageJ.

Other techniques

[edit]- FRET (Förster resonance energy transfer, also known as fluorescence resonance energy transfer) is used to study protein interactions, detect specific nucleic acid sequences and used as biosensors, while fluorescence lifetime (FLIM) can give an additional layer of information.

- Biotechnology: biosensors using fluorescence are being studied as possible Fluorescent glucose biosensors.

- Automated sequencing of DNA by the chain termination method; each of four different chain terminating bases has its own specific fluorescent tag. As the labelled DNA molecules are separated, the fluorescent label is excited by a UV source, and the identity of the base terminating the molecule is identified by the wavelength of the emitted light.

- FACS (fluorescence-activated cell sorting). One of several important cell sorting techniques used in the separation of different cell lines (especially those isolated from animal tissues).

- DNA detection: the compound ethidium bromide, in aqueous solution, has very little fluorescence, as it is quenched by water. Ethidium bromide's fluorescence is greatly enhanced after it binds to DNA, so this compound is very useful in visualising the location of DNA fragments in agarose gel electrophoresis. Intercalated ethidium is in a hydrophobic environment when it is between the base pairs of the DNA, protected from quenching by water which is excluded from the local environment of the intercalated ethidium. Ethidium bromide may be carcinogenic – an arguably safer alternative is the dye SYBR Green.

- FIGS (Fluorescence image-guided surgery) is a medical imaging technique that uses fluorescence to detect properly labeled structures during surgery.

- Intravascular fluorescence is a catheter-based medical imaging technique that uses fluorescence to detect high-risk features of atherosclerosis and unhealed vascular stent devices.[84] Plaque autofluorescence has been used in a first-in-man study in coronary arteries in combination with optical coherence tomography.[85] Molecular agents has been also used to detect specific features, such as stent fibrin accumulation and enzymatic activity related to artery inflammation.[86]

- SAFI (species altered fluorescence imaging) an imaging technique in electrokinetics and microfluidics.[87] It uses non-electromigrating dyes whose fluorescence is easily quenched by migrating chemical species of interest. The dye(s) are usually seeded everywhere in the flow and differential quenching of their fluorescence by analytes is directly observed.

- Fluorescence-based assays for screening toxic chemicals. The optical assays consist of a mixture of environment-sensitive fluorescent dyes and human skin cells that generate fluorescence spectra patterns.[88] This approach can reduce the need for laboratory animals in biomedical research and pharmaceutical industry.

- Bone-margin detection: Alizarin-stained specimens and certain fossils can be lit by fluorescent lights to view anatomical structures, including bone margins.[89]

Forensics

[edit]Fingerprints can be visualized with fluorescent compounds such as ninhydrin or DFO (1,8-Diazafluoren-9-one). Blood and other substances are sometimes detected by fluorescent reagents, like fluorescein. Fibers, and other materials that may be encountered in forensics or with a relationship to various collectibles, are sometimes fluorescent.

Non-destructive testing

[edit]Fluorescent penetrant inspection is used to find cracks and other defects on the surface of a part. Dye tracing, using fluorescent dyes, is used to find leaks in liquid and gas plumbing systems.

Signage

[edit]

Fluorescent colors are frequently used in signage, particularly road signs. Fluorescent colors are generally recognizable at longer ranges than their non-fluorescent counterparts, with fluorescent orange being particularly noticeable.[90] This property has led to its frequent use in safety signs and labels.

Optical brighteners

[edit]Fluorescent compounds are often used to enhance the appearance of fabric and paper, causing a "whitening" effect. A white surface treated with an optical brightener can emit more visible light than that which shines on it, making it appear brighter. The blue light emitted by the brightener compensates for the diminishing blue of the treated material and changes the hue away from yellow or brown and toward white. Optical brighteners are used in laundry detergents, high brightness paper, cosmetics, high-visibility clothing and more.

See also

[edit]- Absorption-re-emission atomic line filters use the phenomenon of fluorescence to filter light extremely effectively.

- Black light

- Blacklight paint

- Fiber photometry

- Fluorescence-activating and absorption-shifting tag

- Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy

- Fluorescence image-guided surgery

- Fluorescence in plants

- Fluorescence spectroscopy

- Fluorescent lamp

- Fluorescent Multilayer Disc

- Fluorometer

- High-visibility clothing

- Integrated fluorometer

- Intrinsic DNA fluorescence

- Laser-induced fluorescence

- List of light sources

- Microbial art, using fluorescent bacteria

- Mössbauer effect, resonant fluorescence of gamma rays

- Organic light-emitting diodes can be fluorescent

- Phosphorescence

- Phosphor thermometry, the use of phosphorescence to measure temperature.

- Spectroscopy

- Two-photon absorption

- Vibronic spectroscopy

- X-ray fluorescence

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Valeur, B.; Berberan-Santos, M.R.N. (2011). "A brief history of fluorescence and phosphorescence before the emergence of quantum theory". Journal of Chemical Education. 88 (6): 731–738. Bibcode:2011JChEd..88..731V. doi:10.1021/ed100182h. S2CID 55366778.

- ^ a b Acuña, A. Ulises; Amat-Guerri, Francisco; Morcillo, Purificación; Liras, Marta; Rodríguez, Benjamín (2009). "Structure and formation of the fluorescent compound of lignum nephriticum" (PDF). Organic Letters. 11 (14): 3020–3023. doi:10.1021/ol901022g. PMID 19586062. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 July 2013.

- ^ Safford, W.E. (1916). "Lignum nephriticum" (PDF). Annual report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 271–298. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 July 2013.

- ^ Muyskens, M.; Vitz, Ed (2006). "The fluorescence of lignum nephriticum: A flash back to the past and a simple demonstration of natural substance fluorescence". Journal of Chemical Education. 83 (5): 765. Bibcode:2006JChEd..83..765M. doi:10.1021/ed083p765.

- ^

Clarke, E.D. (1819). "Account of a newly discovered variety of green fluor spar, of very uncommon beauty, and with remarkable properties of colour and phosphorescence". The Annals of Philosophy. 14: 34–36. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017.

The finer crystals are perfectly transparent. Their colour by transmitted light is an intense emerald green; but by reflected light, the colour is a deep sapphire blue.

- ^ Haüy, R.J. (1822). Traité de Minéralogie [Treatise on Mineralogy] (in French). Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Paris, France: Bachelier and Huzard. p. 512. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Brewster, D. (1834). "On the colours of natural bodies". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 12 (2): 538–545, esp. 542. doi:10.1017/s0080456800031203. S2CID 101650922. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017. On page 542, Brewster mentions that when white light passes through an alcohol solution of chlorophyll, red light is reflected from it.

- ^ Herschel, J. (1845). "On a case of superficial colour presented by a homogeneous liquid internally colourless". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 135: 143–145. doi:10.1098/rstl.1845.0004. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016.

- ^ Herschel, J. (1845). "On the epipŏlic dispersion of light, being a supplement to a paper entitled, "On a case of superficial colour presented by a homogeneous liquid internally colourless"". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 135: 147–153. doi:10.1098/rstl.1845.0005. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017.

- ^ Stokes, G.G. (1852). "On the change of refrangibility of light". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 142: 463–562, esp. 479. doi:10.1098/rstl.1852.0022. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017.

- ^ Qiu, Jianrong; Li, Yang; Jia, Yongchao (2021). Persistent phosphors: from fundamentals to applications. Woodhead publishing series in electronic and optical materials. Duxford Cambridge, MA Kidlington: Woodhead Publishing, an imprint of Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-818772-2.

- ^ Verhoeven, J. W. (1 January 1996). "Glossary of terms used in photochemistry (IUPAC Recommendations 1996)". Pure and Applied Chemistry (in German). 68 (12): 2223–2286. doi:10.1351/pac199668122223. ISSN 1365-3075.

- ^ a b c d e Valeur, Bernard; Berberan-Santos, Mario (2012). Molecular Fluorescence: Principles and applications. Wiley-VCH. p. 64. ISBN 978-3-527-32837-6.

- ^ a b Mallick, Prabal Kumar (2023). Fundamentals of Molecular Spectroscopy. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. doi:10.1007/978-981-99-0791-5. ISBN 978-981-99-0790-8.

- ^ a b c d e Lakowicz, Joseph R. (1999). Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Kluwer Academic / Plenum Publishers. ISBN 978-0-387-31278-1.

- ^ Levitus, Marcia (22 April 2020). "Tutorial: measurement of fluorescence spectra and determination of relative fluorescence quantum yields of transparent samples". Methods and Applications in Fluorescence. 8 (3): 033001. Bibcode:2020MApFl...8c3001L. doi:10.1088/2050-6120/ab7e10. ISSN 2050-6120. PMID 32150732. S2CID 212653274.

- ^ Brouwer, Albert M. (31 August 2011). "Standards for photoluminescence quantum yield measurements in solution". Pure and Applied Chemistry. IUPAC Technical Report. 83 (12): 2213–2228. doi:10.1351/PAC-REP-10-09-31. ISSN 1365-3075. S2CID 98138291.

- ^ Nawara, Krzysztof; Waluk, Jacek (16 April 2019). "Goodbye to quinine in sulfuric acid solutions as a fluorescence quantum yield standard". Analytical Chemistry. 91 (8): 5389–5394. doi:10.1021/acs.analchem.9b00583. ISSN 0003-2700. PMID 30907575. S2CID 85501014. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021.

- ^ "Animation for the Principle of Fluorescence and UV-Visible Absorbance" Archived 9 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine. PharmaXChange.info.

- ^ Schieber, Frank (October 2001). "Modeling the Appearance of Fluorescent Colors". Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting. 45 (18): 1324–1327. doi:10.1177/154193120104501802. S2CID 2439728.

- ^ IUPAC.PAC, 2007, 79, 293. (Glossary of terms used in photochemistry, 3rd edition (IUPAC Recommendations 2006)) on page 360 https://goldbook.iupac.org/terms/view/K03370

- ^ IUPAC. – Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") Archived 21 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Compiled by McNaught, A.D. and Wilkinson, A. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, 1997.

- ^ Excited-State (Anti)Aromaticity Explains Why Azulene Disobeys Kasha's Rule David Dunlop, Lucie Ludvíková, Ambar Banerjee, Henrik Ottosson, and Tomáš Slanina Journal of the American Chemical Society 2023 145 (39), 21569-21575 DOI: 10.1021/jacs.3c07625

- ^ Qian, Hai; Cousins, Morgan E.; Horak, Erik H.; Wakefield, Audrey; Liptak, Matthew D.; Aprahamian, Ivan (January 2017). "Suppression of Kasha's rule as a mechanism for fluorescent molecular rotors and aggregation-induced emission". Nature Chemistry. 9 (1): 83–87. doi:10.1038/nchem.2612. ISSN 1755-4330. PMID 27995926. S2CID 42798987.

- ^ a b c "Fluorescence in marine organisms". Gestalt Switch Expeditions. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015.

- ^ "Fluorescence discovered in tiny Brazilian frogs". Business Standard India. Press Trust of India. 29 March 2019. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Utsav (2 December 2017). "Top 10 Amazing Bioluminescent Animals on Planet Earth". Earth and World. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Ward, William W.; Cormier, Milton J. (1978). "Energy Transfer Via Protein–Protein Interaction in Renilla Bioluminescence". Photochemistry and Photobiology. 27 (4): 389–396. doi:10.1111/j.1751-1097.1978.tb07621.x. S2CID 84887904.

- ^ "Firefly Squid – Deep Sea Creatures on Sea and Sky". www.seasky.org. Archived from the original on 28 June 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d Wucherer, M. F.; Michiels, N. K. (2012). "A Fluorescent Chromatophore Changes the Level of Fluorescence in a Reef Fish". PLOS ONE. 7 (6) e37913. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...737913W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0037913. PMC 3368913. PMID 22701587.

- ^ Fujii, R (2000). "The regulation of motile activity in fish chromatophores". Pigment Cell Research. 13 (5): 300–19. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0749.2000.130502.x. PMID 11041206.

- ^ Abbott, F. S. (1973). "Endocrine Regulation of Pigmentation in Fish". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 13 (3): 885–894. doi:10.1093/icb/13.3.885.

- ^ a b c d e Sparks, J. S.; Schelly, R. C.; Smith, W. L.; Davis, M. P.; Tchernov, D.; Pieribone, V. A.; Gruber, D. F. (2014). Fontaneto, Diego (ed.). "The Covert World of Fish Biofluorescence: A Phylogenetically Widespread and Phenotypically Variable Phenomenon". PLOS ONE. 9 (1) e83259. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...983259S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083259. PMC 3885428. PMID 24421880.

- ^ a b Beyer, Steffen. "Biology of underwater fluorescence". Fluopedia.org. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ Haddock, S. H. D.; Dunn, C. W. (2015). "Fluorescent proteins function as a prey attractant: experimental evidence from the hydromedusa Olindias formosus and other marine organisms". Biology Open. 4 (9): 1094–1104. doi:10.1242/bio.012138. ISSN 2046-6390. PMC 4582119. PMID 26231627.

- ^ Mazel, Charles (2017). "Method for Determining the Contribution of Fluorescence to an Optical Signature, with Implications for Postulating a Visual Function". Frontiers in Marine Science. 4 266. Bibcode:2017FrMaS...4..266M. doi:10.3389/fmars.2017.00266. ISSN 2296-7745.

- ^ Matz, M. "Fluorescence: The Secret Color of the Deep". Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 31 October 2014.

- ^ a b Heinermann, P (10 March 2014). "Yellow intraocular filters in fishes". Experimental Biology. 43 (2): 127–147. PMID 6398222.

- ^ a b c d e Michiels, N. K.; Anthes, N.; Hart, N. S.; Herler, J. R.; Meixner, A. J.; Schleifenbaum, F.; Schulte, G.; Siebeck, U. E.; Sprenger, D.; Wucherer, M. F. (2008). "Red fluorescence in reef fish: A novel signalling mechanism?". BMC Ecology. 8 (1): 16. Bibcode:2008BMCE....8...16M. doi:10.1186/1472-6785-8-16. PMC 2567963. PMID 18796150.

- ^ Gerlach, T; Sprenger, D; Michiels, N. K. (2014). "Fairy wrasses perceive and respond to their deep red fluorescent coloration". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 281 (1787) 20140787. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.0787. PMC 4071555. PMID 24870049.

- ^ Park, Hyun Bong; Lam, Yick Chong; Gaffney, Jean P.; Weaver, James C.; Krivoshik, Sara Rose; Hamchand, Randy; Pieribone, Vincent; Gruber, David F.; Crawford, Jason M. (27 September 2019). "Bright Green Biofluorescence in Sharks Derives from Bromo-Kynurenine Metabolism". iScience. 19: 1291–1336. Bibcode:2019iSci...19.1291P. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2019.07.019. ISSN 2589-0042. PMC 6831821. PMID 31402257.

- ^ Salih, A.; Larkum, A.; Cox, G.; Kühl, M.; Hoegh-Guldberg, O. (2000). "Fluorescent pigments in corals are photoprotective". Nature. 408 (6814): 850–3. Bibcode:2000Natur.408..850S. doi:10.1038/35048564. PMID 11130722. S2CID 4300578. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015.

- ^ Roth, M. S.; Latz, M. I.; Goericke, R.; Deheyn, D. D. (2010). "Green fluorescent protein regulation in the coral Acropora yongei during photoacclimation". Journal of Experimental Biology. 213 (21): 3644–3655. Bibcode:2010JExpB.213.3644R. doi:10.1242/jeb.040881. PMID 20952612.

- ^ Bou-Abdallah, F.; Chasteen, N. D.; Lesser, M. P. (2006). "Quenching of superoxide radicals by green fluorescent protein". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 1760 (11): 1690–1695. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.08.014. PMC 1764454. PMID 17023114.

- ^ Field, S. F.; Bulina, M. Y.; Kelmanson, I. V.; Bielawski, J. P.; Matz, M. V. (2006). "Adaptive Evolution of Multicolored Fluorescent Proteins in Reef-Building Corals". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 62 (3): 332–339. Bibcode:2006JMolE..62..332F. doi:10.1007/s00239-005-0129-9. PMID 16474984. S2CID 12081922.

- ^ Mäthger, L. M.; Denton, E. J. (2001). "Reflective properties of iridophores and fluorescent 'eyespots' in the loliginid squid Alloteuthis subulata and Loligo vulgaris". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 204 (Pt 12): 2103–18. Bibcode:2001JExpB.204.2103M. doi:10.1242/jeb.204.12.2103. PMID 11441052. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ Tsien, R. Y. (1998). "The Green Fluorescent Protein". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 67: 509–544. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.509. PMID 9759496. S2CID 8138960.

- ^ Mazel, C. H. (2004). "Fluorescent Enhancement of Signaling in a Mantis Shrimp". Science. 303 (5654): 51. doi:10.1126/science.1089803. PMID 14615546. S2CID 35009047.

- ^ Bou-Abdallah, F.; Chasteen, N. D.; Lesser, M. P. (2006). "Quenching of superoxide radicals by green fluorescent protein". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 1760 (11): 1690–1695. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.08.014. PMC 1764454. PMID 17023114.

- ^ Douglas, R. H.; Partridge, J. C.; Dulai, K.; Hunt, D.; Mullineaux, C. W.; Tauber, A. Y.; Hynninen, P. H. (1998). "Dragon fish see using chlorophyll". Nature. 393 (6684): 423–424. Bibcode:1998Natur.393..423D. doi:10.1038/30871. S2CID 4416089.

- ^ a b Lamb, J.Y.; M.P. Davis (2020). "Salamanders and other amphibians are aglow with biofluorescence". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 2821. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.2821L. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-59528-9. PMC 7046780. PMID 32108141.

- ^ Wong, Sam (13 March 2017). "Luminous frog is the first known naturally fluorescent amphibian". Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ King, Anthony (13 March 2017). "Fluorescent frog first down to new molecule". Archived from the original on 22 March 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ Taboada, C.; A.E. Brunetti; C. Alexandre; M.G. Lagorio; J. Faivovich (2017). "Fluorescent Frogs: A Herpetological Perspective". South American Journal of Herpetology. 12 (1): 1–13. doi:10.2994/SAJH-D-17-00029.1. hdl:11336/48638. S2CID 89815080.

- ^ a b Sandra Goutte; Matthew J. Mason; Marta M. Antoniazzi; Carlos Jared; Didier Merle; Lilian Cazes; Luís Felipe Toledo; Hanane el-Hafci; Stéphane Pallu; Hugues Portier; Stefan Schramm; Pierre Gueriau; Mathieu Thoury (2019). "Intense bone fluorescence reveals hidden patterns in pumpkin toadlets". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 5388. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.5388G. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-41959-8. PMC 6441030. PMID 30926879.

- ^ Fox, A. (2 April 2019). "Scientists discover a frog with glowing bones". ScienceMag. Archived from the original on 8 March 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ^ Rebouças, R.; A.B. Carollo; M.d.O. Freitas; C. Lambertini; R.M. Nogueira dos Santos; L.F. Toledo (2019). "Conservation Status of Brachycephalus Toadlets (Anura: Brachycephalidae) from the Brazilian Atlantic Rainforest". Diversity. 55 (1): 39–47. Bibcode:2019Diver..11..150B. doi:10.3390/d11090150. hdl:11449/188070.

- ^ Vukusic, P; Hooper, I (2005). "Directionally controlled fluorescence emission in butterflies". Science. 310 (5751): 1151. doi:10.1126/science.1116612. PMID 16293753. S2CID 43857104.

- ^ Arnold, K. E. (2002). "Fluorescent Signaling in Parrots". Science. 295 (5552): 92. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.599.1127. doi:10.1126/science.295.5552.92. PMID 11778040.

- ^ a b Andrews, K.; Reed, S.M.; Masta, S.E. (2007). "Spiders fluoresce variably across many taxa". Biology Letters. 3 (3): 265–267. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0016. PMC 2104643. PMID 17412670.

- ^ Stachel, S.J.; Stockwell, S.A.; van Vranken, D.L. (1999). "The fluorescence of scorpions and cataractogenesis". Chemistry & Biology. 6 (8): 531–539. doi:10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80085-4. PMID 10421760.

- ^ Spaeth, P. (2020). "Biofluorescence in the platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus)". Mammalia. 85 (2): 179–181. doi:10.1515/mammalia-2020-0027.

- ^ McDonald, Maurice S. (2 June 2003). Photobiology of Higher Plants. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-85523-2. Archived from the original on 21 December 2017.

- ^ "5.1 Chlorophyll fluorescence – ClimEx Handbook". Archived from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ Iriel, A. A.; Lagorio, M. A. G. (2010). "Is the flower fluorescence relevant in biocommunication?". Naturwissenschaften. 97 (10): 915–924. Bibcode:2010NW.....97..915I. doi:10.1007/s00114-010-0709-4. PMID 20811871. S2CID 43503960.

- ^ Raman, C.V., (1962). "The luminescence of fluorspar", Curr. Sci., 31, 361–365

- ^ Mobed, Jarafshan J.; Hemmingsen, Sherry L.; Autry, Jennifer L.; McGown, Linda B. (1 September 1996). "Fluorescence characterization of IHSS humic substances: Total luminescence spectra with absorbance correction". Environmental Science & Technology. 30 (10): 3061–3065. Bibcode:1996EnST...30.3061M. doi:10.1021/es960132l. ISSN 0013-936X.

- ^ Milori, Débora MBP; Martin-Neto, Ladislau; Bayer, Cimélio; Mielniczuk, João; Bagnato, Vanderlei S (2002). "Humification degree of soil humic acids determined by fluorescence spectroscopy". Soil Science. 167 (11): 739–749. Bibcode:2002SoilS.167..739M. doi:10.1097/00010694-200211000-00004. ISSN 0038-075X. S2CID 98552138.

- ^ Richard, C; Trubetskaya, O; Trubetskoj, O; Reznikova, O; Afanas' Eva, G; Aguer, J-P; Guyot, G (2004). "Key role of the low molecular size fraction of soil humic acids for fluorescence and photoinductive activity". Environmental Science & Technology. 38 (7): 2052–2057. Bibcode:2004EnST...38.2052R. doi:10.1021/es030049f. ISSN 0013-936X. PMID 15112806.

- ^ Sierra, MMD; Giovanela, M; Parlanti, E; Soriano-Sierra, EJ (2005). "Fluorescence fingerprint of fulvic and humic acids from varied origins as viewed by single-scan and excitation/emission matrix techniques". Chemosphere. 58 (6): 715–733. Bibcode:2005Chmsp..58..715S. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2004.09.038. ISSN 0045-6535. PMID 15621185.

- ^ Dramićanin, Tatjana; Zeković, Ivana; Periša, Jovana; Dramićanin, Miroslav D. (2019). "The Parallel Factor Analysis of Beer Fluorescence". Journal of Fluorescence. 29 (5): 1103–1111. doi:10.1007/s10895-019-02421-0. PMID 31396828.

- ^ Birks, J. B. (1962). "The Fluorescence and Scintillation Decay Times of Crystalline Anthracene". Proceedings of the Physical Society. 79 (3): 494–496. Bibcode:1962PPS....79..494B. doi:10.1088/0370-1328/79/3/306. S2CID 17394465.

- ^ Gilmore, F. R.; Laher, R. R.; Espy, P. J. (1992). "Franck–Condon Factors, r-Centroids, Electronic Transition Moments, and Einstein Coefficients for Many Nitrogen and Oxygen Band Systems". Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 21 (5): 1005. Bibcode:1992JPCRD..21.1005G. doi:10.1063/1.555910. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017.

- ^ "Chemists create the brightest-ever fluorescent materials". phys.org. Archived from the original on 3 September 2020. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ "Scientists create the brightest fluorescent materials in existence". New Atlas. 7 August 2020. Archived from the original on 13 September 2020. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ "Scientists create 'brightest known materials in existence'". independent.co.uk. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ Benson, Christopher R.; Kacenauskaite, Laura; VanDenburgh, Katherine L.; Zhao, Wei; Qiao, Bo; Sadhukhan, Tumpa; Pink, Maren; Chen, Junsheng; Borgi, Sina; Chen, Chun-Hsing; Davis, Brad J.; Simon, Yoan C.; Raghavachari, Krishnan; Laursen, Bo W.; Flood, Amar H. (6 August 2020). "Plug-and-Play Optical Materials from Fluorescent Dyes and Macrocycles". Chem. 6 (8): 1978–1997. Bibcode:2020Chem....6.1978B. doi:10.1016/j.chempr.2020.06.029. ISSN 2451-9294.

- ^ a b Harris, Tom (7 December 2001). "How Fluorescent Lamps Work". HowStuffWorks. Discovery Communications. Archived from the original on 6 July 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Flesch, P. (2006). Light and light sources: high-intensity discharge lamps. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-32685-4. OCLC 262693002.

- ^ Chen, Lei; Lin, Chun-Che; Yeh, Chiao-Wen; Liu, Ru-Shi (22 March 2010). "Light Converting Inorganic Phosphors for White Light-Emitting Diodes". Materials. 3 (3): 2172–2195. Bibcode:2010Mate....3.2172C. doi:10.3390/ma3032172. ISSN 1996-1944. PMC 5445896.

- ^ Rye, H. S.; Dabora, J. M.; Quesada, M. A.; Mathies, R. A.; Glazer, A. N. (1993). "Fluorometric Assay Using Dimeric Dyes for Double- and Single-Stranded DNA and RNA with Picogram Sensitivity". Analytical Biochemistry. 208 (1): 144–150. doi:10.1006/abio.1993.1020. PMID 7679561.

- ^ Harris, Daniel C. (2004). Exploring chemical analysis. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7167-0571-0. Archived from the original on 31 July 2016.

- ^ Fundamental and Details of Laser Welding by Seiji Katayama – Springer 2020 p. 3–5

- ^ Calfon MA, Vinegoni C, Ntziachristos V, Jaffer FA (2010). "Intravascular near-infrared fluorescence molecular imaging of atherosclerosis: toward coronary arterial visualization of biologically high-risk plaques". J Biomed Opt. 15 (1): 011107–011107–6. Bibcode:2010JBO....15a1107C. doi:10.1117/1.3280282. PMC 3188610. PMID 20210433.

- ^ Ughi GJ, Wang H, Gerbaud E, Gardecki JA, Fard AM, Hamidi E, et al. (2016). "Clinical Characterization of Coronary Atherosclerosis With Dual-Modality OCT and Near-Infrared Autofluorescence Imaging". JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 9 (11): 1304–1314. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.11.020. PMC 5010789. PMID 26971006.

- ^ Hara T, Ughi GJ, McCarthy JR, Erdem SS, Mauskapf A, Lyon SC, et al. (2015). "Intravascular fibrin molecular imaging improves the detection of unhealed stents assessed by optical coherence tomography in vivo". Eur Heart J. 38 (6): 447–455. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv677. PMC 5837565. PMID 26685129.

- ^ Shkolnikov, V; Santiago, J. G. (2013). "A method for non-invasive full-field imaging and quantification of chemical species" (PDF). Lab on a Chip. 13 (8): 1632–43. doi:10.1039/c3lc41293h. PMID 23463253. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ^ Moczko, E; Mirkes, EM; Cáceres, C; Gorban, AN; Piletsky, S (2016). "Fluorescence-based assay as a new screening tool for toxic chemicals". Scientific Reports. 6 33922. Bibcode:2016NatSR...633922M. doi:10.1038/srep33922. PMC 5031998. PMID 27653274.

- ^ Smith, W. Leo; Buck, Chesney A.; Ornay, Gregory S.; Davis, Matthew P.; Martin, Rene P.; Gibson, Sarah Z.; Girard, Matthew G. (20 August 2018). "Improving Vertebrate Skeleton Images: Fluorescence and the Non-Permanent Mounting of Cleared-and-Stained Specimens". Copeia. 106 (3): 427–435. doi:10.1643/cg-18-047. ISSN 0045-8511.

- ^ Hawkins, H. Gene; Carlson, Paul John and Elmquist, Michael (2000) "Evaluation of fluorescent orange signs" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Texas Transportation Institute Report 2962-S.

Further reading

[edit]- The Story of Fluorescence. Raytech Industries. 1965.

External links

[edit]- Fluorophores.org, the database of fluorescent dyes

- FSU.edu, Basic Concepts in Fluorescence

- "A nano-history of fluorescence" lecture by David Jameson

- Excitation and emission spectra of various fluorescent dyes

- Database of fluorescent minerals with pictures, activators and spectra (fluomin.org)

- "Biofluorescent Night Dive – Dahab/Red Sea (Egypt), Masbat Bay/Mashraba, "Roman Rock"". YouTube. 9 October 2012.

- Steffen O. Beyer. "FluoPedia.org: Publications". fluopedia.org.

- Steffen O. Beyer. "FluoMedia.org: Science". fluomedia.org.

- Courtney Whitcher. Finding Fluorescence - backyard participation project to identify new examples of fluorescence

![{\displaystyle \left[S_{1}\right]=\left[S_{1}\right]_{0}e^{-\Gamma t}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9862f745e8c8e8f83083c7e8038c0a4c632b6c07)

![{\displaystyle \left[S_{1}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/85875c6a1407cb88df37cff6cac722a1b488dbc2)

![{\displaystyle \left[S_{1}\right]_{0}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8ddfd576e02a185cecd193db9b729e228db24d84)