Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ruffed grouse

View on Wikipedia

| Ruffed grouse Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| A displaying male at Seney National Wildlife Refuge, Michigan, and a female at Algonquin Provincial Park in Ontario | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Galliformes |

| Family: | Phasianidae |

| Tribe: | Tetraonini |

| Genus: | Bonasa Stephens, 1819 |

| Species: | B. umbellus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Bonasa umbellus | |

| |

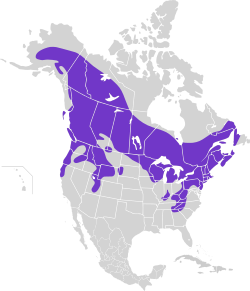

resident range

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus) is a medium-sized grouse occurring in forests from the Appalachian Mountains across Canada to Alaska. It is the most widely distributed game bird in North America.[2] It is not migratory. It is the only species in the genus Bonasa. The ruffed grouse is sometimes incorrectly referred to as a "partridge", an unrelated phasianid, and occasionally confused with the grey partridge, a bird of open areas rather than woodlands.[3]

The ruffed grouse is the state game bird of Pennsylvania, United States.[4]

Taxonomy

[edit]

Bonasa umbellus was first described by Carl Linnaeus in his 1766 12th edition of Systema Naturae.[5] He classified it as Tetrao umbellus, placing it in a subfamily with Eurasian grouse. The genus Bonasa was applied by British naturalist John Francis Stephens in 1819.[6] Ruffed grouse is the preferred common name because it applies only to this species. Misleading vernacular names abound, however, and it is often called partridge (sometimes rendered pa'tridge, or shortened to pat),[7] pheasant, or prairie chicken, all of which are properly applied to other birds.[8] Other nicknames for ruffed grouse include drummer or thunder-chicken.[9]

The ruffed grouse has 13 recognized subspecies:[10]

- B. u. brunnescens (Conover, 1935) - Vancouver Island (Canada)

- B. u. castanea (Aldrich & Friedmann, 1943) - Olympic Peninsula (USA)

- B. u. incana (Aldrich & Friedmann, 1943) - southeastern Idaho to central Utah (USA)

- B. u. labradorensis (Ouellet, 1991) - Labrador Peninsula (Canada)

- B. u. mediana (Todd, 1940) - north-central USA

- B. u. monticola (Todd, 1940) - central towards east-central USA

- B. u. obscura (Todd, 1947) - northern Ontario (Canada)

- B. u. phaios (Aldrich & Friedmann, 1943) - southeastern British Columbia (Canada) to south-central Idaho and eastern Oregon (USA)

- B. u. sabini (Douglas, 1829) - western coast of Canada and USA

- B. u. togata (Linnaeus, 1766) - north-central and northeastern USA and southeastern Canada

- B. u. umbelloides (Douglas, 1829) - southeastern Alaska (USA) through central Canada to central Oregon and northwestern Wyoming (USA)

- B. u. umbellus (Linnaeus, 1766) - east-central USA

Description

[edit]

Ruffed grouse are chunky, medium-sized birds that weigh from 450–750 g (0.99–1.65 lb), measure from 40 to 50 cm (16 to 20 in) in length, and span 50–64 cm (20–25 in) across their short, strong wings.[11] They have two distinct morphs - grey and brown. In the grey morph, the head, neck, and back are grey-brown; the breast is light with barring, with is much white on the underside and flanks. Overall, the birds have a variegated appearance; the throat is often distinctly lighter. The tail is essentially the same brownish grey, with regular barring and a broad black band near the end ("subterminal"). Brown-morph birds have tails of the same color and pattern. However, the rest of the plumage is much more brown, giving the appearance of a more uniform bird with less light plumage below and a conspicuously grey tail. All sorts of intergrades occur between the most typical morphs; warmer and more humid conditions favor browner birds in general.[citation needed]

The ruffs are on the sides of the neck in both sexes. They also have a crest on top of their head, which sometimes lies flat. Both sexes are similarly marked and sized, making them difficult to tell apart, even in hand. The female often has a broken subterminal tail band. At the same time, males tend to have unbroken tail bands, though the opposite of either can occur. Females may also do a display similar to the male. Another fairly accurate sign is that rump feathers with a single white dot indicate a female; rump feathers with more than one white dot indicate a male.[citation needed]

The average lifespan of a ruffed grouse is one year, although some birds are thought to live for as long as 11 years.[12][13] Ruffed grouse are polygynous, and males may mate with several females during the breeding season.[citation needed]

Ecology

[edit]

Like most grouse, they spend most of their time on the ground; mixed woodland rich in aspen seems to be particularly well-liked. These birds forage on the ground or in trees. They are omnivores, eating buds, leaves, berries, seeds, and insects. According to nature writer Don L. Johnson:

More than any other characteristic, it is the ruffed grouse's ability to thrive on a wide range of foods that has allowed it to adapt to such a wide and varied range of habitat on this continent. A complete menu of grouse fare might itself fill a book. One grouse crop yielded a live salamander in a salad of watercress. Another contained a small snake.[14]

Hunting

[edit]

Hunting of the ruffed grouse is common in the northern and far western United States, as well as Canada, often with shotguns. Dogs may also be used. Hunting of the ruffed grouse can be challenging. This is because the grouse spends most of its time in thick brush, aspen stands, and second-growth pines. It is also very hard to detect a foraging grouse bobbing about in the thicket due to their camouflage. With adequate snow cover, they will burrow under the snow. The ruffed grouse will maintain trails through the underbrush and pines like other forest creatures. These can often be found by looking for the bird's feathers on the ground and twigs at the edges of its trail. Hunting of the ruffed grouse requires a good ear and lots of stamina, as one will be constantly walking and listening for them in the leaves.[15]

— Joseph B. Barney

Ruffed grouse frequently seek gravel and clover along roadbeds during early morning and late afternoon. These are good areas to walk during this time to flush birds. Also, grouse use sandy roadbeds to dust their feathers to rid themselves of skin pests. Dusting sites are visible as areas of disturbed soils with some signs of feathers. Birds may return to these spots during the late afternoon to bathe in dust and socialize and mate.[citation needed]

Behavior

[edit]The ruffed grouse differs from other grouse species in its courtship display. The ruffed grouse relies entirely on a nonvocal, acoustic display, known as drumming, unlike other grouse species. The drumming itself is a rapid, wing-beating display that creates a low-frequency sound, starting slow and speeding up (thump ... thump ... thump..thump-thump-thump-thump). Even in thick woods, this can be heard for a quarter-mile (400 m) or more.

The ruffed grouse spends most of its time quietly on the ground, and when surprised, may explode into flight, beating its wings very loudly. It will burrow into the snow for warmth in the winter and may suddenly burst out of the snow when approached too closely.

The male grouse proclaims his territory by engaging in a "drumming" display. This sound is made by beating his wings against the air to create a vacuum.[16] It usually stands on a log, stone, or mound of soil when drumming. It does not strike the log to make the noise, it only uses the "drumming log" as a sort of stage.[17]

The ruffed grouse population has a cycle, and follows the cycle no matter how much or how little hunting occurs. The cycle has puzzled scientists for years, and is simply referred to as the "grouse cycle".[18][19][20][21][22][23][24] In spite of this historical cycle, populations have been declining in Pennsylvania and management plans adopted.[25][26] Habitat loss has been a concern for the species,[27][28][29] but the introduction of the West Nile virus has been seen to be further increasing mortality.[25][26][30][31][32][28]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ BirdLife International (2018). "Bonasa umbellus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018 e.T22679500A131905854. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22679500A131905854.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "Grouse Facts".

- ^ Haupt, J. (2001). "Bonasa umbellus". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ "1931 Act 234". Pennsylvania General Assembly. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ Linnaeus, C. (1766). Systema Naturae.

- ^ Stephens, J. F. (1819). General Zoology, Vol. XI, Pt. II: Aves. Vol. 11. Printed for G. Kearsley. p. 298.

- ^ Johnson, Chuck; Smith, Jason A. (2009). Wingshooter's Guide to North Dakota: Upland Birds and Waterfowl. Wilderness Adventures Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-932098-70-9.

- ^ Fish, Fur & Feathers: Fish and Wildlife Conservation in Alberta 1905-2005. Fish and Wildlife Historical Society and Federation of Alberta Naturalists. 2005. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-9696134-7-3.

- ^ Jezioro, Frank. "January and Grouse Hunting Go Together". West Virginia Dept of Commerce. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ IOC World Bird List 13.1 (Report). doi:10.14344/ioc.ml.13.1. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ^ "Ruffed Grouse – Life History". Allaboutbirds.org. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- ^ "Biology of the Ruffed Grouse (Bonasa umbellus)".

- ^ "Ruffed Grouse Facts, Habitat, Diet, Life Cycle, Baby, Pictures". March 2016.

- ^ Johnson, Don L. (1995). Grouse & Woodcock: A Gunner's Guide. Krause Publications. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-87341-346-6.

- ^ "Ruffed Grouse". Beauty of Birds. 16 September 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- ^ Michael Furtman, Michael (2004). Ruffed Grouse: Woodland Drummer. Stackpole Books. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-8117-3122-5. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ "Grouse Facts". The Ruffed Grouse Society & American Woodcock Society. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ Furtman, Michael (September–October 2010). "Ups and Downs in the Grouse Woods". Minnesota Conservation Volunteer. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ^ "A Firm Stand for the Quaking Aspen". Vault. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "New Hampshire Ruffed Grouse Assessment 2015" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "Grouse cycle nearing 10-year peak". PostBulletin.com. Retrieved 21 June 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Ruffed Grouse - Introduction | Birds of North America Online". birdsna.org. doi:10.2173/bow.rufgro.01. S2CID 216329949. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "Ruffed Grouse Facts, Habitat, Diet, Life Cycle, Baby, Pictures". www.animalspot.net. March 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "RGS History 1960's". www.ruffedgrousesociety.org. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ a b "Pennsylvania 2016 Grouse and Woodcock Status Report" (PDF). p. 7.

- ^ a b "Ruffed Grouse". Wildlife Species. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "Grouse in the Balance" (PDF).

- ^ a b "PA Game Commission giving special management attention to ruffed grouse". centredaily. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "Grouse research leaves unanswered questions about Pennsylvania's state bird | Penn State University". Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ Stauffer, Glenn E.; Miller, David A.W.; Williams, Lisa M.; Brown, Justin (20 September 2017). "Ruffed grouse population declines after introduction of West Nile virus". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 82 (1): 165–172. doi:10.1002/jwmg.21347. ISSN 0022-541X.

- ^ "West Nile Virus PA Game Commission Research Summary" (PDF).

- ^ "Susceptibility of Ruffed Grouse (Bonasa umbellus) to West Nile Virus" (PDF).

Further reading

[edit]- Henninger, W.F. (1906). "A preliminary list of the birds of Seneca County, Ohio" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 18 (2): 47–60.

- Ohio Ornithological Society (2004): Annotated Ohio state checklist.

- State Symbols of Pennsylvania: State Bird, The Ruffed Grouse PDF fulltext

External links

[edit]- "Ruffed grouse media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Ruffed grouse photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Ruffed Grouse Species Account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Ruffed grouse hen video Appalachian Mountains, Floyd Virginia

- Interactive range map of Bonasa umbellus at IUCN Red List

.jpg/250px-Ruffed_Grouse_(18645551408).jpg)

.jpg/2000px-Ruffed_Grouse_(18645551408).jpg)