Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Neurocranium

View on Wikipedia| Neurocranium | |

|---|---|

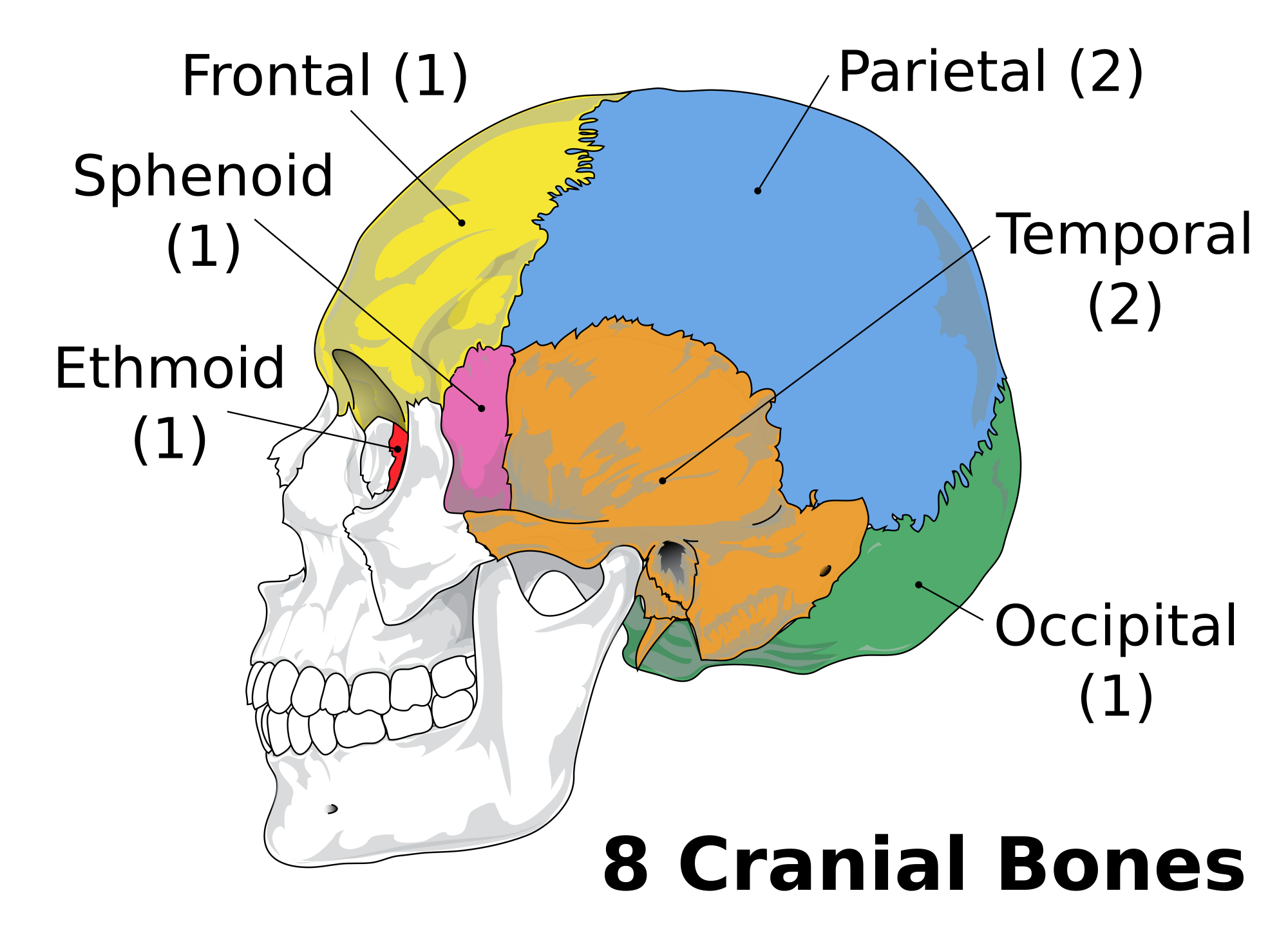

The eight bones that form the human neurocranium. | |

The eight cranial bones. (Facial bones are shown in transparent.)

Yellow: Frontal bone (1)

Blue: Parietal bone (2)

Purple: Sphenoid bone (1)

Brown: Temporal bone (2)

Green: Occipital bone (1)

Red: Ethmoid bone (1) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | neurocranium |

| TA98 | A02.1.00.007 |

| TA2 | 354 |

| FMA | 53672 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

In human anatomy, the neurocranium, also known as the braincase, brainpan, brain-pan,[1][2] or brainbox, is the upper and back part of the skull, which forms a protective case around the brain.[3] In the human skull, the neurocranium includes the calvaria or skullcap. The remainder of the skull is the facial skeleton.

In comparative anatomy, neurocranium is sometimes used synonymously with endocranium or chondrocranium.[4]

Structure

[edit]The neurocranium is divided into two portions:

- the membranous part, consisting of flat bones, which surround the brain; and

- the cartilaginous part, or chondrocranium, which forms bones of the base of the skull.[3]

In humans, the neurocranium is usually considered to include the following eight bones:

The ossicles (three on each side) are usually not included as bones of the neurocranium.[6] There may variably also be extra sutural bones present.

Below the neurocranium is a complex of openings (foramina) and bones, including the foramen magnum which houses the neural spine. The auditory bullae, located in the same region, aid in hearing.[7]

The size of the neurocranium is variable among mammals. The roof may contain ridges such as the temporal crests.

Development

[edit]The neurocranium arises from paraxial mesoderm. There is also some contribution of ectomesenchyme. In Chondrichthyes and other cartilaginous vertebrates this portion of the cranium does not ossify; it is not replaced via endochondral ossification.

Other animals

[edit]The neurocranium is formed by the combination of the endocranium, the lower portions of the cranial vault, and the skull roof. Through the course of evolution, the human neurocranium has expanded from comprising the back part of the mammalian skull to being also the upper part: during the evolutionary expansion of the brain, the neurocranium has overgrown the splanchnocranium. The upper-frontmost part of the cranium also houses the evolutionarily newest part of the mammal brain, the frontal lobes.

In other vertebrates, the foramen magnum is oriented towards the back, rather than downwards. The braincase contains a greater number of bones, most of which are endochondral rather than dermal:[8]

- The singular basioccipital is the rear lower part of the braincase, below the foramen magnum. It is homologous to the basilar part of the occipital bone. In the ancestral tetrapod, the basioccipital makes up most of a large central knob-like surface, the occipital condyle, which articulates with the vertebrae as a ball-and-socket joint. This plesiomorphic ("primitive") state is retained by modern reptiles and birds. The underside of the basioccipital may have a pair of large projections which act as neck muscle attachments: the basitubera (also known as basioccipital tubera or basal tubera)

- The paired exoccipitals (singular: exoccipital) are visible at the rear of the braincase, adjacent to the foramen magnum and above the basioccipital. They are homologous to the lateral parts of the occipital bone. Modern amphibians and mammals have independently acquired inflated exoccipitals, acting as paired occipital condyles while the basioccipital is reduced and loses its connection to the vertebrae.

- The singular supraoccipital is the rear upper part of the braincase, above the foramen magnum and below or behind the parietals or postparietals. It is homologous to the squamous part of the occipital bone, which is greatly enlarged in humans.

- The paired opisthotics (singular: opisthotic) form most of the rear lateral part of the braincase, in front of the exoccipitals and above the foramen ovale. They also contribute to the paroccipital process, a lateral projection which acts as a buttress between the braincase and the outer skull bones. In many tetrapods, the opisthotic is fused to its corresponding exoccipital. The jugular foramen is usually found near the point of fusion.

- The paired prootics (singular: prootic) form the lateral part of the braincase, in front of the opisthotics. The front edge of the prootic is typically deeply notched by the exit hole for the trigeminal nerve (V). Many other nerve exits are scattered among the prootic, opisthotic, and exoccipital. The prootic is homologous to the petrous part of the temporal bone (in humans) or the petrosal bone (in other mammals).

- Some reptiles have a laterosphenoid in front of the prootic. This bone is present in archosaurs and a few other archosauromorphs, as well as the stem-turtle Proganochelys.

- The singular basisphenoid forms the front lower part of the braincase, in front of the basioccipital and below the prootics. Each side of the basisphenoid hosts a basipterygoid process, a lateral rod which bends down and out to link to the pterygoid bones of the bony palate. The basisphenoid may also act as a component of the basitubera.

- The singular parasphenoid is one of the few dermal components of the braincase, a flat plate below the basisphenoid. The parasphenoid acts as a component of the bony palate, wedging between the pterygoid bones and often ornamented with small tooth-like denticles. In many vertebrates the parasphenoid and basisphenoid are fused into a single bone, the parabasisphenoid. The front part of the parabasisphenoid is a blade-like structure, the cultriform process, which extends much further forward than the rest of the braincase.

Additional images

[edit]-

Inner surface of base of skull.

-

Neurocranium (labeled as "Brain case") and facial bones.

-

3D model. Click to move.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Brainpan - Medical Definition and More from Merriam-Webster". Merriam-Webster/Medical.

- ^ Nyiszli, Miklos (2011). Auschwitz: A Doctor's Eyewitness Account. New York: Arcade Publishing.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ a b Sadler, Thomas W. (February 2009). Langman's Medical Embryology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 173. ISBN 978-0781790697.

- ^ Kent, George C.; Carr, Robert K. (2001). Comparative Anatomy of the Vertebrates (9th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-303869-5.

- ^ In small children, the frontal bone is still separated into two parts, by the frontal suture, which normally closes during postnatal development.

- ^ but if they are included, the neurocranium will then have to be said to consist of fourteen bones

- ^ Elbroch, M. 2006. Animal skulls: A guide to North American species. Stackpole Books, pp. 20–22. ISBN 978-0-8117-3309-0

- ^ Currie, P.J. (1997). "Braincase Anatomy". In Currie, P.J.; Padian, K. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. pp. 81–85. ISBN 978-0-12-226810-6.

External links

[edit]External links

[edit] Media related to Neurocranium at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Neurocranium at Wikimedia Commons