Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Callanish.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Callanish

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

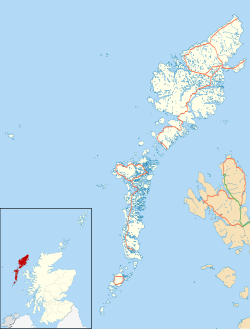

Calanais (English: Callanish) is a village (township) on the west side of the Isle of Lewis, in the Outer Hebrides (Western Isles), Scotland. Calanais is within the parish of Uig.[1] A linear settlement with a jetty, it is on a headland jutting into Loch Roag, a sea loch 13 miles (21 kilometres) west of Stornoway. Calanais is situated alongside the A858, between Breasclete and Garynahine.[citation needed]

Key Information

The Calanais Stones "Calanais I", a cross-shaped setting of standing stones erected around 3000 BC, are one of the most spectacular megalithic monuments in Scotland. A modern visitor centre provides information about the main circle and other lesser monuments nearby, numbered as Calanais II to X.

References

[edit]- ^ "Details of Callanish". Scottish Places. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

External links

[edit]Wikimedia Commons has media related to Callanish.

- Calanais Visitor Centre

- Breasclete Community Association (local area's website)

- Panoramas of the Callanish Standing Stones (QuickTime required)

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Lewis, Callanish (Site no. NB23SW 19)".

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Calanais, Calanais and Bhreascleit War Memorial (Site no. NB23SW 98)".

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Lewis, Callanish, Tea Rooms (Site no. NB23SW 78)".

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Lewis, Callanish, Pier (Site no. NB23SW 18)".

- A Statistical Analysis of Megalithic Sites in Britain : Alexander Thom - Alexander Thom

Callanish

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

The Callanish Stones, also known as the Calanais Standing Stones, are a prehistoric Neolithic monument located on the west coast of the Isle of Lewis in Scotland's Outer Hebrides.[1] Consisting of a central stone circle with radiating arms forming a cruciform pattern, the site features 49 standing stones originally erected around 2900–2600 BCE, making it older than Stonehenge's main circle.[1] Crafted from local Lewisian gneiss—a 3-billion-year-old metamorphic rock—the stones, some reaching up to 4.8 meters in height, were quarried from nearby outcrops and arranged in a central ring of 13 monoliths around a taller central pillar, with four avenues extending outward.[2][3]

Archaeological excavations, particularly those conducted between 1979 and 1988, have revealed that the monument's construction occurred in phases: the initial stone circle around 2900 BCE, followed by the addition of the northern avenue and chambered cairn around 2400 BCE, indicating prolonged ritual use over centuries.[3] Beneath the central setting lies a burial cairn containing human remains and artifacts such as pottery and quartz arrowheads, suggesting the site functioned as a ceremonial center possibly linked to funerary practices.[1] The stones' alignments, particularly toward the midwinter sunset and the Moon's major standstill cycle (occurring every 18.6 years), point to potential astronomical observations, though their exact purpose remains a subject of ongoing research.[3][1]

As one of Scotland's most significant prehistoric sites, the Callanish Stones offer vital insights into Neolithic society, including advanced stone-working techniques and cultural connections across the British Isles.[1] Managed by Historic Environment Scotland and accessible year-round free of charge, the monument attracts visitors interested in its enduring mystery and the broader context of megalithic architecture; ongoing efforts include the Calanais 2025 project to enhance visitor facilities.[4][5] Recent geophysical surveys and conservation efforts continue to uncover associated features, underscoring the site's layered 6,000-year history of human activity.[6]

.JPG/250px-View_to_Callanish_village_from_Callanish_Stones_in_summer_2012_(3).JPG)

.JPG/2000px-View_to_Callanish_village_from_Callanish_Stones_in_summer_2012_(3).JPG)