Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Isle of Lewis

View on Wikipedia

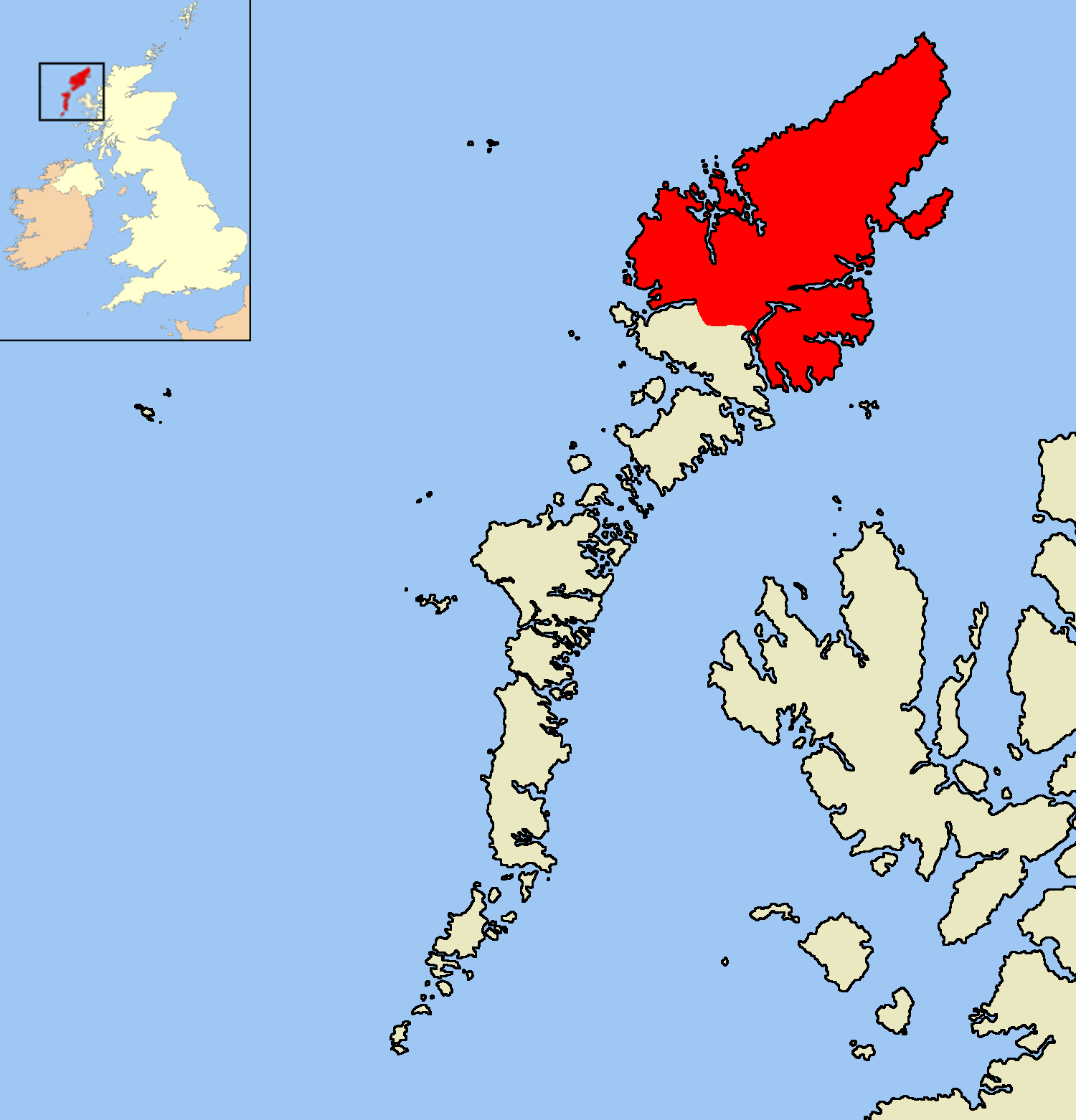

The Isle of Lewis[2] (Scottish Gaelic: Eilean Leòdhais, pronounced [ˈelan ˈʎɔːəs̪] ⓘ) or simply Lewis is the northern part of Lewis and Harris, the largest island of the Western Isles or Outer Hebrides archipelago in Scotland. The two parts are frequently referred to as if they were separate islands. The total area of Lewis is 683 square miles (1,770 km2).[3]

Key Information

Lewis is, in general, the lower-lying part of the island: the other part, Harris, is more mountainous. Due to its larger area and flatter, more fertile land, Lewis contains three-quarters of the population of the Western Isles, and the largest settlement, Stornoway. The island's diverse habitats are home to an assortment of flora and fauna, such as the golden eagle, red deer and seal, and are recognised in a number of conservation areas.

Lewis has a Presbyterian tradition and a rich history. It was once part of the Norse Kingdom of the Isles. Today, life is very different from elsewhere in Scotland, with Sabbath observance, the Scottish Gaelic language and peat cutting retaining more importance than elsewhere. Lewis has a rich cultural heritage as can be seen from its myths and legends as well as the local literary and musical traditions.

Name

[edit]| Scots Gaelic: | Eilean Leòdhais | |

| Pronunciation: | [elan ˈʎɔːəʃ] ⓘ | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Eilean an Fhraoich | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈelan ən̪ˠ rˠɯːç] ⓘ | |

The Scottish Gaelic name Leòdhas may be derived from Norse Ljoðahús ('song house'),[4] although other origins have been suggested – most notably the Gaelic leogach ('marshy').[5] It is probably the place referred to as Limnu by Ptolemy, which also means 'marshy'.[6] It is also known as the Isle of Lewis (Gaelic: Eilean Leòdhais). Another name usually used in a cultural or poetic context is Eilean an Fhraoich ('Heather Isle'),[4] although this refers to the whole of the island of Lewis and Harris.

History

[edit]The earliest evidence of human habitation on Lewis is found in peat samples which indicate that about 8,000 years ago much of the native woodland was torched to make way for plants to allow deer to browse. The earliest archaeological remains date from about 5,000 years ago. At that time, people began to settle in permanent farms rather than following their herds. The small houses of these people have been found throughout the Western Isles; in particular, at Dail Mòr, Carloway. The more striking great monuments of this period are the temples and communal burial cairns at places like Calanais (English: Callanish).

About 500 BC, island society moved into the Iron Age. The buildings became larger and more prominent, culminating in the brochs – circular, dry-stone towers belonging to the local chieftains – which testify to the uncertain nature of life then. The best remaining example of a broch in Lewis is at Dùn Chàrlabhaigh (English: Dun Carloway). The Scots arrived during the first centuries AD, bringing the Scottish Gaelic language with them.[7] As Christianity began to spread through the islands in the 6th and later centuries, following Columban missionaries, Lewis was inhabited by the Picts.[7]

In the 9th century AD, the Vikings began to settle on Lewis, after years of raiding from the sea. The Norse invaders intermarried with local people and abandoned their pagan beliefs. At that time, rectangular buildings began to supersede round ones, following the Scandinavian style. Lewis became part of the Kingdom of Mann and the Isles, an offshoot of Norway. The Lewis chessmen, found on the island in 1831, date from the time of Viking rule.[8] The people were called the Norse Gaels or Gall-Ghàidheil (lit. "Foreigner Gaels"), reflecting their mixed Scandinavian/Gaelic background, and probably their bilingual speech.[9] The Norse language persists in many island placenames and some personal names to this day, although the latter are fairly evenly spread across the Gàidhealtachd.

Lewis (and the rest of the Western Isles) became part of Scotland once more in 1266: under the Treaty of Perth it was ceded by the Kingdom of Norway. Under Scottish rule, the Lordship of the Isles emerged as the most important power in north-western Scotland by the 14th century. The Lords of the Isles were based on Islay, but controlled all of the Hebrides. They were descended from Somerled (Somhairle) Mac Gillibride, a Gall-Ghàidheil lord who had held the Hebrides and West Coast two hundred years earlier. Control of Lewis itself was initially exercised by the Macleod clan, but after years of feuding and open warfare between and even within local clans, the lands of Clan MacLeod were forfeited to the Scottish Crown in 1597 and were awarded by King James VI to a group of Lowland colonists known as the Fife adventurers in an attempt to anglicise the islands. However the adventurers were unsuccessful, and possession passed to the Mackenzies of Kintail in 1609, when Coinneach, Lord MacKenzie, bought out the lowlanders.[7]

Following the 1745 rebellion, and Prince Charles Edward Stewart's flight to France, the use of Scottish Gaelic was discouraged, rents were demanded in cash rather than kind, and the wearing of folk dress was made illegal. Emigration to the New World increasingly became an escape for those who could afford it during the latter half of the century. In 1844 Lewis was bought by Sir James Matheson, co-founder of Jardine Matheson, but subsequent famine and changing land use forced vast numbers off their lands and increased the flood of emigrants again. Paradoxically, those who remained became ever more congested[clarification needed] and impoverished, as large tracts of arable land were set aside for sheep, deerstalking or grouse shooting. Agitation for land resettlement became acute on Lewis during the economic slump of the 1880s, with several land raids (in common with Skye, Uist and Tiree); this quietened down as the island economy recovered.

During the First World War, thousands of islanders served in the forces, many losing their lives, including 208 naval reservists from the island who were returning home after the war when the Admiralty yacht HMY Iolaire sank within sight of Stornoway harbour. Many servicemen from Lewis served in the Royal Navy and the Merchant Navy during the Second World War, and again many people died. Afterwards, many more inhabitants emigrated to the Americas and mainland Scotland.

In May 1918 the Isle of Lewis was purchased by the soap magnate Lord Leverhulme, who intended to make Stornoway an industrial town and build a fish cannery. His plans were initially popular, but his opposition to land resettlement led to further land raids, especially around the farms of Coll, Gress and Tong. These raids, commemorated in monuments in several villages,[7] were ultimately successful, as the government was prepared to take legal action in support of land resettlement. Faced with this, Leverhulme gave up on his plans for Lewis and concentrated his efforts on Harris, where the town of Leverburgh takes his name.

Historical sites

[edit]The Isle of Lewis has a variety of locations of historical and archaeological interest, including:

- Callanish Stones (Tursachan Chalanais) associated with the Clan Morrison among others

- Dun Carloway Broch

- Iron Age houses near Bostadh (Great Bernera)

- The Garenin blackhouse village in Carloway and the Black House at Arnol

- Bragar whale bone arch

- St Columba's church in Aignish

- Teampull Mholuaidh in Ness

- Clach an Truiseil monolith

- Clach an Tursa, Carloway

- Bonnie Prince Charlie's Monument, Arnish

- Lews Castle

- Butt of Lewis cliffs and Butt of Lewis Lighthouse

- Dùn Èistean, a small island which is the ancestral home of the Lewis Clan Morrisons of the Ness area

- Ui Church, burial place of the Clan Chiefs MacLeod of Lewis and MacKenzie

There are also numerous lesser stone circles and the remains of five further brochs.

Geography and geology

[edit]

Much of Lewis consists of mostly sandy beaches backed by dunes and machair on the Atlantic west coast, giving way to an expansive peat-covered plateau in the centre of the island. The eastern coastline is markedly more rugged and is mostly rocky cliffs broken by small coves and beaches. The more fertile nature of the eastern side led to the majority of the population settling there, including the largest settlement and only town, Stornoway. Aside from the village of Achmore in the centre of the island, all settlements are on the coast.[10]

Compared with Harris, Lewis is relatively flat, except in the south-west, where Mealaisbhal, 574 m (1,883 ft), is the highest point, and in the south-east, where Beinn Mhor reaches 572 m (1,877 ft); but there are 16 high points exceeding 300 m (980 ft) in height.[11] Southern Lewis also has a large number of freshwater lochs compared to the north of the island.

South Lewis, Harris and North Uist together comprise a National Scenic Area. There are four geographical Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) on Lewis – Glen Valtos, Cnoc a' Chapuill, Port of Ness and Tolsta Head.[12][13]

The coastline is severely indented, creating a number of large sea lochs, such as Lochs Resort and Seaforth, which form part of the border with Harris, Loch Roag, which surrounds the island of Great Bernera, and Loch Erisort. The principal capes are the Butt of Lewis, in the extreme north, with hundred foot (30 m) cliffs (the high point is 142 ft (43 m) high)[14] and crowned with a lighthouse, the light of which is visible for 19 miles (31 km); Tolsta Head, Tiumpan Head and Cabag Head, on the east; Renish Point, in the extreme south; and, on the west, Toe Head and Gallon Head.[15] The largest island associated with Lewis is Bernera or Great Bernera in the district of Uig and is linked to the mainland of Lewis by a bridge opened in 1953.

Geology

[edit]

The geology of Lewis is dominated by the Archean aged metamorphic gneisses of the eponymous Lewisian complex.[16] Despite sharing a name with the mainland Lewisian Complex, the Lewisian on Lewis is often considered to be from a different block, generally interpreted as the lower plate of a orogeny, than most of the mainland examples of Lewisian.[17] Exceptions are a patch of granite near Carloway, small bands of intrusive basalt at Gress and in Eye Peninsula and some sandstone at Stornoway, Tong, Vatisker and Carloway, which was originally thought to be Torridonian,[15] but is now considered more likely to be Permo-Triassic in age.[18] The North of the Island contains a Paleoproterozoic, predominantly amphibolite, supracrustal belt, the Ness Complex, which contains meta-anorthosite and has disputedly been correlated to the South Harris Granulite Belt.[19]

Climate

[edit]Exposure to the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf Stream lead to a cool, moist climate on Lewis. There is relatively little temperature difference between summer and winter, both of which are moderately cloudy (although cloud and wet weather often blows over quickly in summer). Both seasons also have significant rainfall and frequent high winds, particularly during the autumn equinox. These winds have led to Lewis being designated a potential site for a significant wind-farm, which has caused much controversy amongst the population.

| Climate data for Lewis | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.0 (44.6) |

7.4 (45.3) |

8.7 (47.7) |

11.0 (51.8) |

12.7 (54.9) |

15.0 (59.0) |

16.7 (62.1) |

16.2 (61.2) |

14.7 (58.5) |

12.2 (54.0) |

9.5 (49.1) |

7.5 (45.5) |

11.6 (52.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.8 (37.0) |

3.0 (37.4) |

3.1 (37.6) |

4.6 (40.3) |

6.4 (43.5) |

9.1 (48.4) |

10.9 (51.6) |

10.8 (51.4) |

9.6 (49.3) |

7.4 (45.3) |

5.0 (41.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

6.3 (43.3) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 118.8 (4.68) |

136.4 (5.37) |

150.4 (5.92) |

84.8 (3.34) |

124.8 (4.91) |

98.0 (3.86) |

119.0 (4.69) |

150.6 (5.93) |

141.2 (5.56) |

187.0 (7.36) |

165.0 (6.50) |

224.4 (8.83) |

1,700.4 (66.95) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 34.5 | 63.4 | 104.9 | 147.1 | 192.2 | 166.4 | 127.9 | 132.6 | 106.6 | 77.2 | 44.3 | 26.2 | 1,223.3 |

| Source 1: Met Office (Data January 1874 – November 2006)

Temperature figures are average figures for that month; other figures are averages of monthly totals. | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Hebrides Weather[20] | |||||||||||||

Nature

[edit]There are 15 Sites of Special Scientific Interest on Lewis in the biology category, spread across the island. Additionally, the Lewis Peatlands are recognised by Scottish Natural Heritage as a Special Protection Area, Special Area of Conservation and a Ramsar site, showing their importance as a wetland habitat for migratory and resident bird life.[13]

Birds

[edit]Many species of seabirds inhabit the coastal areas of Lewis, including shag, gannet, fulmar, kittiwake, guillemot, and gulls. Red grouse and woodcock are found in the interior.

In the Uig hills, it is possible to spot both golden and white-tailed eagles.[21] In the Pairc area, oystercatchers and curlews can be seen. A few pairs of peregrine falcons inhabit the coastal cliffs and merlin and buzzard are common everywhere on hill and moor. An important feature of the winter bird life is the great diversity of wildfowl. Several species of waterfowl, including eider and long-tailed duck, are found in the shallow water around Lewis.[22]

Marine life

[edit]

Salmon frequent several Lewis rivers after crossing the Atlantic. Many of the fresh-water lochs are home to fish such as trout. Other freshwater fish present include Arctic char, European eel, 3 and 9 spined sticklebacks, thick-lipped mullet and flounder.

Offshore, it is common to see grey seals, particularly in Stornoway harbour, and with luck, dolphins, harbour porpoises, sharks and even the occasional whale can be encountered.[23]

Land mammals

[edit]There are only two native land mammals in the Western Isles: red deer and otter. The rabbit, mountain hare, hedgehog, feral cat, polecat and both brown and black rats were introduced. The origin of mice and voles is uncertain.[22]

American mink, another introduced species (escapees from fur farms), cause problems for native ground-nesting birds, the local fishing industry and poultry farmers.[24] Mink have been successfully eradicated[25] from the Uists and Barra. The second and ongoing phase of the Hebridean Mink Project aims to rid Lewis and Harris of mink in similar fashion.[26]

There are claims that the Stornoway castle grounds are home to bats.[27] In addition, some residents keep farm animals such as Hebridean sheep, Highland cattle or kyloe and a few pigs.

Reptiles and amphibians

[edit]

In common with Ireland, no snakes inhabit Lewis,[28] only the slowworm which is merely mistaken for a snake. Actually, a legless lizard, it is the sole member of its order present. The common frog may be found in the centre of the island[28] though it, along with any newts or toads present are introduced species.[22]

Insects

[edit]The island's most famous insect resident is the Scottish midge which is ever-present near water at certain times of the year.

During the summer months, several species of butterflies and dragonflies can be found, especially around Stornoway.

The richness of insect life in Lewis is evident from the abundance of carnivorous plants that thrive in parts of the island.

Flora

[edit]

The machair is noted for different species of orchid and associated vegetation such as various grasses. Three heathers; ling, bell heather and cross-leaved heath are predominant in the large areas of moorland vegetation which also holds large numbers of insectivorous plants such as sundews. The expanse of heather-covered moorland explains the name Eilean an Fhraoich, Scottish Gaelic for "The Heather Isle".[29]

Lewis was once covered by woodland, but the only natural woods remaining are in small pockets on inland cliffs and on islands within lochs, away from fire and sheep. In recent years, Forestry Commission plantations of spruce and pine were planted, although most of the pines were destroyed by moth infestation. The most important mixed woods are those planted around Lews Castle in Stornoway, dating from the mid-19th century.[30]

Politics and government

[edit]

Historically, while Harris was part of Inverness-shire, Lewis was part of Ross-shire or Ross and Cromarty. The Western Isles Islands Council was established in 1975. Now called Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, its remit covers the whole of the Outer Hebrides and its headquarters are in Stornoway.

Lewis is home to the majority of the Western Isles' electorate and six of the nine multi-member council wards are within Lewis and one is shared with Harris. 22 councillors are effectively elected by Lewis residents using the Single Transferable Vote system, and following the 2007 elections 19 are independents, one has Labour and two SNP party affiliation.[32]

The Isle of Lewis is in the Highlands electoral region and is part of the identical Na h-Eileanan an Iar Scottish Parliamentary and Na h-Eileanan an Iar Westminster constituencies, currently represented by a member of the Scottish National Party (SNP) and by a member of the Labour Party after the last election.

Current representatives

[edit]- UK Parliament: Torcuil Crichton MP (Labour Party), first elected in 2024

- Scottish Parliament: Alasdair Allan MSP (SNP), first elected in 2007

Demographics

[edit]Lewis' main settlement, the only burgh on the Outer Hebrides, is Stornoway (Scottish Gaelic: Steòrnabhagh), from which ferries sail to Ullapool on the Scottish mainland. In the 2011 census Lewis had a population of 19,658.

The island's settlements are on or near the coasts or sea lochs, being particularly concentrated on the north east coast. The interior of the island is a large area of moorland from which peat was traditionally cut as fuel, although this practice has become less common. The southern part of the island, adjoining Harris, is more mountainous with inland lochs.

Parishes and districts of Lewis

[edit]- There are four parishes: Barvas (Barabhas), Lochs (Na Lochan), Stornoway (Steòrnabhagh), and Uig on which the original civil registration districts were based. The district of Carloway (after the village of that name) which hitherto had fallen partly within the parishes of Lochs and Uig, became a separate civil registration district in 1859.

- The districts of Lewis are Ness (Nis), Carloway (Càrlabhagh), Back, Lochs (Na Lochan), Park (A' Phàirc), Point (An Rubha), Stornoway, West Side, Bernera and Uig. These designations are traditional and in use by the entire population.

- For civil registration purposes Lochs (Na Lochan) is nowadays split into North Lochs (Na Lochan a Tuath) and South Lochs (Na Lochan a Deas).

- The West Side is a generic designation for the area covering the villages from Borve to Dalbeg (Siabost).

It is claimed that the site of the Stornoway War Memorial was chosen as it would be visible from at least one location in each of the four parishes; therefore, it may be possible to see all four parishes of Lewis from the top of the monument.[33]

Settlements

[edit]While Lewis has only one town, Stornoway, with a population of approx 8,000, there are also several large villages and groupings of villages on Lewis, such as North Tolsta, Carloway and Leurbost with significant populations. Near Stornoway, Laxdale, Sandwick and Holm, although still de facto villages, have now become quasi-suburbs of Stornoway. The population of the greater-Stornoway area including these (and other) villages would be nearer 12,000. The island of Great Bernera contains the first planned crofting township created in the Outer Hebrides, Kirkibost created in 1805. This village was subsequently 'cleared' in 1823 and re-settled in 1878 using the exact land lotting divisions from 1805.

The following is a non-exhaustive list of villages in Lewis according to their location:

- Back

- Back, Coll, Gress, North Tolsta, Tong

- Ness

- Melbost, South Galson, North Galson, South Dell, North Dell, Cross, Swainbost, Habost, Lionel, Port of Ness, Eoropie, Fivepenny, Knockaird, Adabrock, Eorodale, Skigersta, Cross-Skigersta Road

- North Lochs

- Achmore, Grimshader, Leurbost, Ranish, Crossbost, Keose, Keose Glebe, Laxay, Balallan, Airidhbhruaich

- Park (South Lochs)

- Shieldenish, Habost, Kershader, Garyvard, Caverstay, Cromore, Marvig, Calbost, Gravir, Lemreway, Orinsay

- Point

- Aird, Aignish, Flesherin, Lower Bayble, Portnaguran, Portvoller, Sheshader, Shulishader, Upper Bayble, Eagleton

- Uig

- Aird Uig, Cliff, Kneep, Timsgarry, Valtos, Breanish, Islivik, Meavag, Mangursta, Crowlista, Geishader, Carishader, Gisla, Carloway, Garynahine, Callanish, Breasclete, Breaclete, Kirkibost, Tobson, Hacklete

- West Side

- Arnol, Ballantrushal, Barvas, Borve, Bragar, Brue, Shader, Shawbost, Dalbeg

- Stornoway area

- Branahuie, Holm, Laxdale, Marybank, Melbost, Newmarket, Newvalley, Parkend, Plasterfield, Sandwick, Steinish

Economy

[edit]

Traditional industries on Lewis are crofting, fishing and weaving. Though historically important, they are currently in decline and crofting in particular is little more than a subsistence venture today. Over 40% of the working population is employed by the public sector (chiefly Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, the local authority; and NHS Western Isles). Tourism is the only growing commercial industry.

According to the Scottish Government, "tourism is by far and away the mainstay industry" of the Outer Hebrides, "generating £65m in economic value for the islands, sustaining around 1000 jobs". The report adds that the "islands receive 219,000 visitors per year".[34] The Outer Hebrides tourism bureau states that 10–15% of economic activity on the islands was made up of tourism in 2017. The agency states that the "exact split between islands is not possible" when calculating the number of visits, but "the approximate split is Lewis (45%), Uist (25%), Harris (20%), Barra (10%)".[35]

Despite the name, the Harris tweed industry is today focused in Lewis, with the major finishing mills in Shawbost and Stornoway. Every length of cloth produced is stamped with the official Orb symbol, trademarked by the Harris Tweed Association in 1909, when Harris Tweed was defined as "hand-spun, hand-woven and dyed by the crofters and cottars in the Outer Hebrides"; Machine-spinning and vat dyeing have since replaced hand methods, and only weaving is now conducted in the home, under the governance of the Harris Tweed Authority, established by an Act of Parliament in 1993. Harris Tweed is now defined as "hand woven by the islanders at their homes in the Outer Hebrides, finished in the islands of Harris, Lewis, North Uist, Benbecula, South Uist and Barra and their several purtenances (The Outer Hebrides) and made from pure virgin wool dyed and spun in the Outer Hebrides."[36]

Aside from the concentration of industry and services in the Stornoway area, many of the historical sites have associated visitor centres, shops or cafes.[37] There is a pharmaceutical plant near Breasclete which specialises in fatty acid research.[38]

The main fishing fleet (and associated shoreside services) in Stornoway is somewhat reduced from its heyday, but many smaller boats perform inshore creel fishing and operate from smaller, local harbours right around Lewis. There are fish farms in many of the sea lochs, and along with the onshore processing and transportation required the industry as a whole is a major employer.

Commerce

[edit]Stornoway is the commercial centre of Lewis; there are several national chains with shops in the town, two national supermarket chains as well as numerous local businesses. Outwith Stornoway, many villages have an all-purpose shop (often combined with a post office). Some villages have more than one, with these usually being specialist stores such as pharmacies or petrol stations. There are almost no rural public houses (for the sale of alcohol); instead, local hotels or inns function as meeting, eating and drinking places, often with accommodation provided. Recently, Abhainn Dearg distillery at Carnish, Uig, on the Isle of Lewis is producing Scotch whisky, the first legal whisky in over 200 years.

Itinerant, travelling shops also tour the island visiting some of the more remote locations. The ease of transport to Stornoway and the advent of the internet have led to many of the village shops closing in recent times. Mobile banking services are provided to remote villages by the Royal Bank of Scotland's travelling bank.

Transport

[edit]

A daily Caledonian MacBrayne ferry (MV Loch Seaforth) sails from Stornoway to Ullapool on the Scottish mainland, taking 2 hours 30 minutes connecting Lewis with the mainland. There are two return crossings a day, with one on a Sunday in the winter. Other ferries sailing from Harris are easily accessible by road, enabling transport to Skye and Uist.

Suggestions for the possibility of an undersea tunnel linking Lewis to the Scottish mainland were raised in early 2007. One of the possible routes, between Stornoway and Ullapool, would be over 50 miles (80 km) long and hence the longest road tunnel in the world;[39][40] however, shorter routes would be possible.

Stornoway is the public transport hub of Lewis, with bus services to Point, Ness, Back and Tolsta, Uig, the West Side, Lochs and Tarbert, Harris. These services are provided by the local authority and several private operators as well as some community-run organisations.

Stornoway Airport is 2 miles (3 km) away from the town itself and is located next to the village of Melbost. Loganair operate services to Edinburgh, Inverness and Glasgow. Hebridean Air Services operate a service to Benbecula. Eastern Airways flights to Aberdeen ended in November 2018. The airport is the base of a HM Coastguard Search & Rescue Sikorsky S-92 helicopter and was previously home to RAF Stornoway.

Peats

[edit]

Peat is still cut as a fuel in many areas of Lewis. Peat is usually cut in late spring with a tool called a tairsgeir (that is, a peat iron, peat spade, peat knife or tosg; sometimes toirsgian) which has a long wooden handle with an angled blade on one end. The peat bank is first cleared of heather turfs. The peat, now exposed, is cut using the tairsgeir and the peats thrown out on the bank to dry. A good peat cutter can cut 1000 peats in a day.[41]

Once dried, the peats are carted to the croft and built into a large stack. These often resembled the shape of the croft house – broad, curved at each end and tapered to a point about 2 metres high. They varied in length from about 4 to 14 metres. Peat stacking also follows local customs and a well-built peat stack can be a work of art. Peat stacks provide additional shelter to houses. A croft can burn as many as 15,000–18,000 peats in a year.[41]

The odour of the peat-smoke, especially in wintertime, can add to the general atmosphere of the island. While peat burning still goes on, there has been a significant decline in recent years as people move to other, less labour-intensive forms of heating; however, it remains an important symbol of island life. In 2008, with the large increase in the price (and theft) of liquefied petroleum gas and heating oil, there were signs that there may be a return to peat cutting.

Religion

[edit]

Religion is important in Lewis, with much of the population belonging to the Free Church or the Church of Scotland (both Presbyterian in tradition). The Sabbath is generally observed, with most shops and licensed premises closed on that day, although there has been a scheduled air service to mainland Scotland as well as a scheduled ferry service since 19 July 2009.[42]

While Presbyterianism dominates Lewis, other denominations and other religions have a presence, with a Catholic church, a Scottish Episcopal Church (part of the Anglican Communion); there is also a Catholic priest of the Anglican Ordinariate in Stornoway,[43] a Salvation Army corps, a Pentecostal church (New Wine Church), a Plymouth Brethren church, a Baptist church, a meetinghouse of the LDS Church and a Jehovah's Witness Kingdom Hall all present in Stornoway.[citation needed] The island's first mosque opened in Stornoway in May 2018.[44]

Some churches in Lewis practise precenting the line, a distinctive, heterophonic style of congregational psalm singing in Scottish Gaelic.[45][46]

Education

[edit]School education in Lewis is under the remit of Comhairle nan Eilean Siar. There are a total of 15 schools covering the 5–18 age range.[47] Unusual features are the prevalence of Scottish Gaelic medium education (offered in 12 of 14 primary schools)[48] and the Nicolson Institute, the only secondary school on the island. The large number of village schools led to necessarily small rolls, and falls in pupil numbers led to the closures of all of the rural secondary departments and some of the primary schools.[49]

Stornoway is home to a small campus of the University of Stirling, teaching nursing, which is based in Ospadal nan Eilean (Western Isles Hospital). There is also a further education college, Lews Castle College, which is part of the UHI Millennium Institute. The college is the umbrella organisation for other vocational and community education, offered in several rural learning centres as well as on the main campus and covering subjects such as basic computer skills, Scottish Gaelic language classes and maritime qualifications.[50]

Culture and sport

[edit]Language

[edit]

Lewis has a linguistic heritage rooted in Scottish Gaelic and Old Norse, which both continue to influence life in Lewis. Today, both Scottish Gaelic and English are spoken in Lewis, but in day-to-day life, a hybrid of English and Scottish Gaelic is very common.[51] As a result of the Scottish Gaelic influence, the Lewis accent of Highland English is frequently considered to sound more Irish or Welsh than stereotypically Scottish in some quarters. The Scottish Gaelic culture in the Western Isles is more prominent than in any other part of Scotland. Scottish Gaelic is the language of choice amongst many islanders and around 60% of islanders speak Scottish Gaelic as a daily language, whilst 70% of the resident population have some knowledge of Scottish Gaelic (including reading, writing, speaking or a combination of the three). The Gaelic Language is considered to be unstable in the Western Isles,[52] though there are some efforts to stabilise, including Gaelic medium education and the Gaelic cultural centre and community café, An Taigh Cèilidh, in Stornoway.

Most of the place names in Lewis and Harris come from Old Norse. The name "Lewis" is the English spelling of the Scottish Gaelic Leòdhas which comes from the Old Norse Ljóðhús, as Lewis is named in medieval Norwegian maps of the island. Various suggestions have been made as to a Norse meaning such as "song house". The name is not of Gaelic origin, the Norse credentials are questionable and it may have a pre-Celtic root.[53][54]

Media and the arts

[edit]As well as regularly playing host to the Royal National Mòd, there are annual local mòds. Stornoway Castle Green hosts the annual 3-day Hebridean Celtic Festival in July, attracting over 10,000 visitors. The festival includes events such as cèilidhs, dances and special concerts featuring storytelling, song and music with performers from all round the Isles and beyond. Sad Day We Left the Croft is a 2007 compilation album of punk bands from Lewis.

The radio station Isles FM is based in Stornoway and broadcasts on 103FM, featuring a mixture of Scottish Gaelic and English programming. The town is also home to a studio operated by BBC Radio nan Gàidheal, and Studio Alba, an independent television studio from where the Scottish Gaelic TV channel TeleG was broadcast.

The Stornoway Gazette is the main local paper, covering Lewis and beyond and is published weekly. The Hebridean is a sister paper of the Gazette and also provides local coverage.[55] Some community organisations in the rural districts have their own publications with news and features for these particular areas, such as the Rudhach for the Point district.[56][57]

Lewis has been home to, or inspired, many writers, including bestselling contemporary author Kevin MacNeil, whose cult novel The Stornoway Way was set in the island's capital. In April 2020, the Isle of Lewis Distillery published a list of 10 recommended books that feature the Outer Hebrides.[58] Parts of the crime/mystery series by author GR Jordan are also set in this area, with the action in Water's Edge and Horror Weekend taking place primarily on the Isle.

Sport

[edit]

There is a good provision of sporting grounds and sports centres in Lewis. Sports such as football, rugby union and golf are popular:

- Football, which grew in popularity after the first World War, is the most popular amateur sport in Lewis with Goathill Park in Stornoway hosting special matches involving select teams and visiting clubs and other organisations. Local teams currently participate in the Lewis and Harris Football League.

- Shinty which was traditionally played in the island as in the rest of the Scottish Gaelic-speaking areas of Scotland, died out by the mid-20th century at the latest. However, it was revived in the 1990s and there is now a strong local club known as Lewis Camanachd which competes in national competition.

- The village of Tong about 2 miles (3 km) from Stornoway plays host to the Highland Games and the Western Isles Strongest man competition each summer.

- Attached to the Nicolson Institute School is the Ionad Spors Leòdhais (Lewis Sports Centre), an all-weather pitch and running track.

- The Lews Castle Grounds is the home of Stornoway Golf Club (the only 18-hole golf course in the Outer Hebrides).

- Angling is a very popular pastime in Lewis as there are several good lochs and rivers for fishing.

- As Lewis is an island, various water sports, such as surfing are popular activities.

- Lewis has a terrain very suited to hillwalking, particularly in Uig and near the border with Harris.

Myths and legends

[edit]The Isle of Lewis has a rich folklore, including Seonaidh – a water-spirit who had to be offered ale in the area of Teampull Mholuaidh in Ness – and The Blue Men who inhabited the Minch, between Lewis and the Shiants.[59]

Gastronomy

[edit]- Each year, men from Ness go out to the island of Sula Sgeir in late August for two weeks to harvest young gannets known locally as Guga, which are a local delicacy.

Notable residents

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2019) |

- Aonghas Caimbeul, Scottish Gaelic war poet, World War II POW, and author of the award-winning memoir Suathadh ri Iomadh Rubha.[60]

- Alistair Darling, Baron Darling of Roulanish, of Great Bernera in the county of Ross and Cromarty,[61] former Chancellor of the Exchequer and MP for Edinburgh Central, had a converted blackhouse at Breaclete and had ancestral links with Great Bernera.[62]

- Kenny Boyle, from Cromore, award winning actor, author, and playwright[63]

- Kenneth Grant Fraser, pioneer Christian missionary doctor in South Sudan

- Sheilagh M. Kesting, first woman minister to be nominated to be Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland

- Stephen Libby, winner of the BBC series, The Traitors, series 4 [64]

- Dòmhnall MacAmhlaigh professor, scholar, and Scottish Gaelic poet

- Angus MacAskill, the tallest non-pathological giant in recorded history (7 ft 9 in, or 2.36 m) – born in Berneray and briefly lived in Stornoway before emigrating to Canada

- Murdo Stewart MacDonald from Great Bernera – Clipper Captain and Lloyds Surveyor of Shipping

- Callum Macdonald from Great Bernera – Foremost publisher of Scottish poetry in the 20th century

- Cathy MacDonald, BBC Alba television presenter; comes from Iarsiadar, Uig

- John MacKay, anchorman of STV News at 6 Central

- Alexander MacKenzie, explorer, for whom the Mackenzie River in Canada is named

- Colin Mackenzie, 1st Surveyor-General of India

- Anne MacKenzie, BBC current affairs presenter and radio presenter

- Ken MacLeod, science fiction writer

- Maighread Stiùbhart, Gaelic singer and folklorist

- Mary Anne MacLeod, mother of U.S. president Donald Trump

- Kevin MacNeil, novelist, poet and playwright

- Donald Macrae, physician, professor of neurology at University of California San Francisco School of Medicine. Awarded the Military Cross in World War II.[65][66]

- Hans Matheson, plays the title role in a television serialisation of Boris Pasternak's novel, Doctor Zhivago

- Alyth McCormack, singer

- Iain Morrison, musician

- John Munro, Scottish Gaelic war poet and winner of the Military Cross during World War I

- Linda Norgrove, kidnapped by the Taliban in Afghanistan, and killed in rescue effort

- Arthur Pink, Christian evangelist and Biblical scholar

- Donald Stewart, politician and former President of the Scottish National Party

- Louisa Caroline Stewart-Mackenzie (1827–1903) socialite and art collector

- Derick Thomson, Scottish Gaelic poet, from Point, and educated in Stornoway

- Alasdair White, musician (Fiddle, Whistle, Pipes, Bouzouki) plays with Battlefield Band

References

[edit]- ^ "Lewis Peatlands". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ "Isle of Lewis/Eilean Leтdhais". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- ^ Thompson, Francis (1968) Harris and Lewis. Newton Abbott. David & Charles. Page 15. The sub-totals provided are: Land – 404,184 acres (163,567 ha); inland water – 24,863 acres (10,062 ha); saltmarsh – 230 acres (93 ha); foreshore – 7,775 acres (3,146 ha); tidal water – 150 acres (61 ha).

- ^ a b Iain Mac an Tailleir. "Placenames" (PDF). Pàrlamaid na h-Alba. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ Murray, W.H. (1966) The Hebrides. London. Heinemann. p. 173.

- ^ "The Roman Map of Britain". Archived from the original on 27 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d Macdonald, D. (1978). Lewis: A History of the Island. Edinburgh: Gordon Wright

- ^ Madden, F. (1832). "Historical remarks on the introduction of the game of chess into Europe and on the ancient chessmen discovered in the Isle of Lewis." Archaeologia 24, 203–291.

- ^ "Heritage History Factfile". Archived from the original on 17 October 2007.

- ^ Pankhurst R.J. & Mullin, J.M. (1991) Flora of the Outer Hebrides, London: HMSO

- ^ [1] Archived 22 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "National Scenic Areas" Archived 11 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. SNH. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ a b "Natural Spaces - Scottish Natural Heritage". gateway.snh.gov.uk.

- ^ "Digital gallery - National Library of Scotland". digital.nls.uk.

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 525–526.

- ^ Park, R.G.; Stewart, A.D.; Wright, D.T. (2003). "3. The Hebridean terrane". In Trewin N.H. (ed.). The Geology of Scotland. London: Geological Society. pp. 45–61. ISBN 978-1-86239-126-0.

- ^ Park, R. G. (November 2005). "The Lewisian terrane model: a review". Scottish Journal of Geology. 41 (2): 105–118. Bibcode:2005ScJG...41..105P. doi:10.1144/sjg41020105. ISSN 0036-9276.

- ^ Steel, Ronald J.; Wilson, Alan C. (1 April 1975). "Sedimentation and tectonism (?Permo-Triassic) on the margin of the North Minch Basin, Lewis". Journal of the Geological Society. 131 (2): 183–200. Bibcode:1975JGSoc.131..183S. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.131.2.0183. S2CID 129036870 – via jgs.geoscienceworld.org.

- ^ Mason, Andrew J. (March 2012). "Major early thrusting as a control on the Palaeoproterozoic evolution of the Lewisian Complex: evidence from the Outer Hebrides, NW Scotland". Journal of the Geological Society. 169 (2): 201–212. Bibcode:2012JGSoc.169..201M. doi:10.1144/0016-76492011-099. ISSN 0016-7649.

- ^ "Hebrides Weather - Temperature Summary Reports".

- ^ "White-tailed Eagle". Visit Outer Hebrides. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ a b c "Wildlife Fact File". cne-siar.gov.uk. 29 September 2008. Archived from the original on 7 November 2008.

- ^ "Marine Life". Visit Outer Hebrides.

- ^ "SNH – Hebridean Mink Project". Archived from the original on 8 October 2007. Retrieved 30 October 2007.

- ^ "New campaign waged against mink". 1 September 2006 – via BBC News.

- ^ "Hebridean Mink Project". Archived from the original on 8 October 2007. Retrieved 30 October 2007.

- ^ "An Introduction to the Bats of Scotland" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ a b Morris, Dr P. (1984). Animals of Britain, Field Guide to the. London: Reader's Digest Association

- ^ "News | The Scotsman". www.scotsman.com.

- ^ "Fact File". 14 September 2008. Archived from the original on 14 September 2008.

- ^ "Article on flags for Hebridean Islands". Archived from the original on 9 April 2014.

- ^ "Wards and Councillors". www.cne-siar.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 20 August 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ Stornoway Historical Society. Archived 7 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Outer Hebrides | Scotland.org". Scotland.

- ^ "Tourism in the Outer Hebrides". Outer Hebrides.

- ^ Harris Tweed Authority, "Fabric History", retrieved 21 May 2007. Archived 15 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Calanais Standing Stones & Visitor centre // Ionad-tadhail Tursachan Chalanais".

- ^ Scottish Enterprise – Life Sciences Directory

- ^ "Proposal for Island tunnel to mainland". Stornoway Today. 2 February 2007. Archived from the original on 8 February 2007.

- ^ Kelbie, Paul (7 February 2007). "Storms inspire dream of Western Isles tunnel". news.independent.co.uk. Archived from the original on 20 December 2007.

- ^ a b "Am Baile Education – Crofting".

- ^ "BBC Scotland News". BBC News. 14 July 2009. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ^ "Stornoway - Ordinariate Scotland". www.ordinariate.scot. Archived from the original on 10 January 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ Britain's rural Muslims are a minority within a minority The Economist, 17 May 2018

- ^ Meek, Noel (November 2016). "Noel Meek explores the sights and sounds of Scottish Gaelic psalm singing". The Wire. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ "Gaelic Psalm: The congregation of Back Free Church, Isle of Lewis". BBC. 6 May 2016. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ "Local Authority Education Dept". Archived from the original on 13 October 2008.

- ^ "Local Authority – Gaelic Medium". Archived from the original on 23 June 2007. Retrieved 4 November 2007.

- ^ "Plans to close 11 island schools". BBC News. 23 August 2007.

- ^ "Lews Castle College – Learning Centres". Archived from the original on 14 June 2007.

- ^ "Linguae-Celticae.Org" (PDF). Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- ^ Conchúr Ó Giollagáin; Gòrdan Camshron; Pàdruig Moireach; Brian Ó Curnáin; Iain Caimbeul; Brian MacDonald; Tamás Péterváry (2020). The Gaelic Crisis in the Vernacular Community. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press. ISBN 978-1-85752-080-4.

- ^ Gammeltoft, Peder "Scandinavian Naming-Systems in the Hebrides – A Way of Understanding how the Scandinavians were in Contact with Gaels and Picts?" in Ballin Smith et al. (2007) p. 487

- ^ Mac an Tàilleir (2003)

- ^ Johnston Press – Publishers Archived 13 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "rudhach.com". www.rudhach.com. Archived from the original on 30 April 2008. Retrieved 4 November 2007.

- ^ "– Breasclete Community Newspaper". Archived from the original on 12 December 2006.

- ^ "10 Books to connect you to Harris". Harris Distillery. 24 April 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ "Wonder Tales from Scottish Myth and Legend: Chapter V. Nimble Men, Blue Men, and Green Ladies". www.sacred-texts.com.

- ^ Ronald Black (1999), An Tuil: Anthology of 20th century Scottish Gaelic Verse, pg. 757.

- ^ "The Rt Hon Lord Darling". Chatham House. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ Angus Howarth (20 March 2004). "Darling hit with holiday home tax". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2007.

- ^ "Is Kenny The First Cromore Actor?". 27 November 2020.

- ^ Laing, Katie. "Island pride and joy as Stephen wins Traitors in honourable style". Stornoway Gazette. Retrieved 25 January 2026.

- ^ "My Story: Part 2: Stolinsky | Conservative Political & Social Commentary".

- ^ "Donald Macrae, Neurology: San Francisco". Calisphere. University of California. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Ballin Smith, Beverley; Taylor, Simon; and Williams, Gareth (2007) West over Sea: Studies in Scandinavian Sea-Borne Expansion and Settlement Before 1300. Leiden. Brill.

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

- Iain Mac an Tàilleir (2003). "Placenames" (PDF). Pàrlamaid na h-Alba. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- Thompson, Francis (1968) Harris and Lewis, Outer Hebrides. Newton Abbot. David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-4260-6

External links

[edit] Lewis travel guide from Wikivoyage

Lewis travel guide from Wikivoyage- Visitor's guide for the Isle of Lewis

- hebrides.ca Home of the Quebec-Hebridean Scots who were cleared from Lewis to Quebec 1838–1920s

- Website of the Western Isles Council with links to other resources

- Panoramas of the Island (QuickTime required)

- Wind power dilemma for Lewis

- Disabled access to Lewis for residents and visitors

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 525–526.

- Dedicated Isle of Lewis Chessmen Website