Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Calender

View on Wikipedia

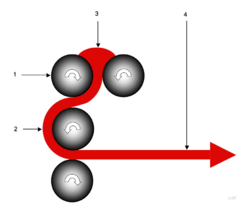

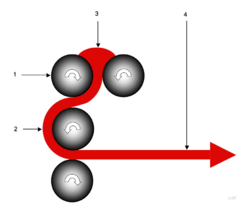

A calender is a series of hard pressure rollers used to finish a sheet of material such as paper, textiles, rubber, or plastics. Calender rolls are also used to form some types of plastic films and to apply coatings.[1] Some calender rolls are heated or cooled as needed.[2] Calenders are sometimes misspelled calendars.

Etymology

[edit]The word "calender" itself is a derivation of the word κύλινδρος kylindros, the Greek word that is also the source of the word "cylinder".[3]

History

[edit]Calender mills for pressing serge were apparently introduced to the Netherlands by Flemish refugees from the Eighty Years' War in the 16th and 17th centuries.[4]

In eighteenth century China, workers called "calenderers" in the silk- and cotton-cloth trades used heavy rollers to press and finish cloth.

In 1836, Edwin M. Chaffee, of the Roxbury India Rubber Company, patented a four-roll calender to make rubber sheet.[5] Chaffee worked with Charles Goodyear with the intention to "produce a sheet of rubber laminated to a fabric base".[6] Calenders were also used for paper and fabrics long before later applications for thermoplastics. With the expansion of the rubber industry the design of calenders grew as well, so when PVC was introduced the machinery was already capable of processing it into film.[6] As recorded in an overview on the history of the development of calenders, "There was development in both Germany and the United States and probably the first successful calendering of PVC was in 1935 in Germany, where in the previous year the Hermann Berstorff Company of Hannover designed the first calender specifically to process this plastic".[6]

In the past, for paper, sheets were worked on with a polished hammer or pressed between polished metal sheets in a press. With the continuously operating paper machine it became part of the process of rolling the paper (in this case also called web paper).[7] The pressure between the rollers, the "nip pressure", can be reduced by heating the rolls or moistening the paper surface. This helps to keep the bulk and the stiffness of the web paper which is beneficial for its later use.

Modern calenders have hard heated rollers made from chilled cast iron or steel, and soft rollers coated with polymeric composites. The soft roller is slightly non-cylindrical, tapered in diameter toward both ends, to widen the working nip and distribute the specific pressure on the paper more evenly.

Calendering paper

[edit]In a principal paper application, the calender is located at the end of a papermaking process (on-line). Those that are used separately from the process (off-line) are also called supercalenders. The purpose of a calender is to make the paper smooth and glossy for printing and writing, as well as of a consistent thickness for capacitors that use paper as their dielectric membrane.

The calender section of a paper machine consists of a calender and other equipment. The paper web is run between in order to further smooth it out, which also gives it a more uniform thickness. The pressure applied to the web by the rollers determines the finish of the paper, in three basic types:

- machine finish, or MF Paper, which can range from a rough, matte (non glossy) look, to a smooth, high-quality finish.

- supercalendered finish, or MG Paper (Machine Glazed), glossy/glazed and suitable for high-degree, fine-screened halftone printing.

- plater finish, obtained by placing cut sheets of paper between stacked zinc or copper plates and put under pressure and heat. A special finish such as a linen finish would be achieved by placing a piece of linen between the plate and the sheet of paper, or else an embossed steel roll might be used.

After calendering, the web has a moisture content of about 6% (depending on the finish). It is wound onto a roll called a tambour, and stored for final cutting and shipping.

Supercalender

[edit]A supercalender is a stack of calenders consisting of alternating steel- and fiber-covered rolls through which paper is passed to increase its density, smoothness and gloss. It is similar to a calender except that alternate chilled cast-iron and softer rolls are used. The rolls used to supercalender uncoated paper usually consist of cast iron and highly compressed paper, while the rolls used for coated paper are usually cast iron and highly compressed cotton. The finish produced varies according to the raw material used to make the paper and the pressure exerted on it, and ranges from the highest English finish to a highly glazed surface. Supercalendered papers are sometimes used for books containing fine line blocks or halftones because they print well from type and halftones, although for the latter they are not as good as coated paper.

Calendering textiles

[edit]Calendering is a finishing process used on cloth and fabrics. A calender is employed, usually to smooth, coat, or thin a material.

With textiles, fabric is passed under rollers at high temperatures and pressures. Calendering is used on fabrics such as moire to produce its watered effect and also on cambric and some types of sateens.

Various man-made fabrics made from synthetic materials are also calendered.

Other materials

[edit]

Calenders can also be applied to materials other than paper and textiles when a smooth, flat surface is desirable.

Polymers such as vinyl and ABS polymer sheets, and to a lesser extent HDPE, polypropylene and polystyrene, are calendered.

The calender is also an important processing machine in the rubber industries, especially in the manufacture of tires, where it is used for the inner layer and fabric layer.

Calendering can also be used for polishing, or making uniform, coatings applied to substrates- an older use was in polishing magnetic tapes, for which the contact roller rotates much faster than the web speed. More recently, it is used in the production of certain types of secondary battery cells (such as spirally-wound or prismatic lithium-ion cells) to achieve uniform thickness of electrode material coatings on current collector foils.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ US5167894A, Wilfried W. Baumgarten, "Apparatus comprising an extruder and a calender for producing sheets and/or foils from plastic or rubber mixtures", published 1992

- ^ US4425489A, Pav, Lauscher, "Electromagnetic heating system for calender rolls or the like", published 1984

- ^ "Definition of CALENDER". www.merriam-webster.com.

- ^ Van Uytven, R. (1971). "The Fulling Mill: Dynamic of the Revolution in Industrial Attitudes". Acta Historiae Neerlandica. V: 12.

- ^ White, James Lindsay (July 20, 1990). Principles of Polymer Engineering Rheology. Wiley-Interscience. p. 49. ISBN 9780471853626. Retrieved 2014-12-25.

- ^ a b c Simpson, W. G. (December 31, 1995). Plastics: Surface and Finish. Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 52. ISBN 9780854045167. Retrieved 2014-12-25.

- ^ "International Paper - Web Paper". Archived from the original on 2009-04-10. Retrieved 2018-11-17.

General references

[edit]- Westerlund Leslie. C. " How to Make Smooth Papermaking Technology" ISBN 1-876141-55-7;Westerlund Eco Services; Rockingham; W.Australia. 2008.

- Hawkins, William E, The Plastic Film and Foil Web Handling Guide CRC Press 2003

- Jenkins, W. A., and Osborn, K. R. Plastic Films: Technology and Packaging Applications, CRC Press 1992

- Yam, K. L., "Encyclopedia of Packaging Technology", John Wiley & Sons, 2009, ISBN 978-0-470-08704-6