Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cassiterite

View on Wikipedia| Cassiterite | |

|---|---|

Cassiterite surrounded by muscovite, from Xuebaoding, Huya, Pingwu, Mianyang, Sichuan, China (size: 100 × 95 mm, 1128 g) | |

| General | |

| Category | Oxide minerals |

| Formula | SnO2 |

| IMA symbol | Cst[1] |

| Strunz classification | 4.DB.05 |

| Crystal system | Tetragonal |

| Crystal class | Ditetragonal dipyramidal (4/mmm) H-M symbol: (4/m 2/m 2/m) |

| Space group | P42/mnm |

| Unit cell | a = 4.7382(4) Å, c = 3.1871(1) Å; Z = 2 |

| Identification | |

| Color | Black, brownish black, reddish brown, brown, red, yellow, gray, white; rarely colorless |

| Crystal habit | Pyramidic, prismatic, radially fibrous botryoidal crusts and concretionary masses; coarse to fine granular, massive |

| Twinning | Very common on {011}, as contact and penetration twins, geniculated; lamellar |

| Cleavage | {100} imperfect, {110} indistinct; partings on {111} or {011} |

| Fracture | Subconchoidal to uneven |

| Tenacity | Brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 6–7 |

| Luster | Adamantine to adamantine metallic, splendent; may be greasy on fractures |

| Streak | White to brownish |

| Diaphaneity | Transparent when light colored, dark material nearly opaque; commonly zoned |

| Specific gravity | 6.98–7.1 |

| Optical properties | Uniaxial (+) |

| Refractive index | nω = 1.990–2.010 nε = 2.093–2.100 |

| Birefringence | δ = 0.103 |

| Pleochroism | Pleochroic haloes have been observed. Dichroic in yellow, green, red, brown, usually weak, or absent, but strong at times |

| Fusibility | infusible |

| Solubility | insoluble |

| References | [2][3][4][5][6] |

Cassiterite is a tin oxide mineral, SnO2. It is generally opaque, but it is translucent in thin crystals. Its luster and multiple crystal faces produce a desirable gem. Cassiterite was the chief tin ore throughout ancient history and remains the most important source of tin today.

Occurrence

[edit]Most sources of cassiterite today are found in alluvial or placer deposits containing the weathering-resistant grains. The best sources of primary cassiterite are found in the tin mines of Bolivia, where it is found in crystallised hydrothermal veins. Rwanda has a nascent cassiterite mining industry. Fighting over cassiterite deposits (particularly in Walikale) is a major cause of the conflict waged in eastern parts of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[7][8] This has led to cassiterite being considered a conflict mineral.

Cassiterite is a widespread minor constituent of igneous rocks. The Bolivian veins and the 4500 year old workings of Cornwall and Devon, England, are concentrated in high temperature quartz veins and pegmatites associated with granitic intrusives. The veins commonly contain tourmaline, topaz, fluorite, apatite, wolframite, molybdenite, and arsenopyrite. The mineral occurs extensively in Cornwall as surface deposits on Bodmin Moor, for example, where there are extensive traces of a hydraulic mining method known as streaming. The current major tin production comes from placer or alluvial deposits in Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, the Maakhir region of Somalia, and Russia. Hydraulic mining methods are used to concentrate mined ore, a process which relies on the high specific gravity of the SnO2 ore, of about 7.0.

Crystallography

[edit]Crystal twinning is common in cassiterite and most aggregate specimens show crystal twins. The typical twin is bent at a near-60-degree angle, forming an "elbow twin". Botryoidal or reniform cassiterite is called wood tin.

Cassiterite is also used as a gemstone and collector specimens when quality crystals are found.

Etymology

[edit]The name derives from the Greek κασσίτερος (transliterated as "kassiteros") for "tin".[9] Early references to κασσίτερος can be found in Homer's Iliad, such as in the description the Shield of Achillies. For example, the passage in book 18 chapter 610:

αὐτὰρ ἐπεὶ δὴ τεῦξε σάκος μέγα τε στιβαρόν τε,

610τεῦξ᾽ ἄρα οἱ θώρηκα φαεινότερον πυρὸς αὐγῆς,

τεῦξε δέ οἱ κόρυθα βριαρὴν κροτάφοις ἀραρυῖαν

καλὴν δαιδαλέην, ἐπὶ δὲ χρύσεον λόφον ἧκε,

τεῦξε δέ οἱ κνημῖδας ἑανοῦ κασσιτέροιο.[10]

Translated as:

then wrought he for him a corselet brighter than the blaze of fire, and he wrought for him a heavy helmet, fitted to his temples, a fair helm, richly-dight, and set thereon a crest of gold; and he wrought him greaves of pliant tin. But when the glorious god of the two strong arms had fashioned all the armour[11]

Liddell-Scott-Jones suggest the etymology to be originally Elamite; citing the Babylonian kassi-tira, hence the sanskrit kastīram.[9] However the Akkadian word (the lingua franca of the Ancient Near East, including Babylonia) for tin was "anna-ku"[12] (cuneiform: 𒀭𒈾[13]). Roman Ghirshman (1954) suggests, from the region of the Kassites, an ancient people in west and central Iran; a view also taken by J D Muhly.[14] There are relatively few words in Ancient Greek at begin with "κασσ-";[15] suggesting that it is an ethnonym.[16] Attempts at understanding the etymology of the word were made in antiquity, such as Pliny the Elder in his Historia Naturalis (book 34 chapter 37.1):

"White lead (tin) is the most valuable; the Greeks applied to it the name cassheros".[17]

And Stephanus of Byzantium in his Ethnica states:

"Κασσίτερα νησοσ εν τω Ωκεανω, τη Ίνδικη προσεχης, ως Διονυσιοσ εν Βασσαρικοισ. Εξ ης ο κασσίτερος."[16]

Which can be translated as:

Kassitera, an island in the ocean, neighbouring India, as Dionysius states in the Bassarika. From there comes tin.

Use

[edit]It may be primarily used as a raw material for tin extraction and smelting.

Gallery

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Warr, L.N. (2021). "IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols". Mineralogical Magazine. 85 (3): 291–320. Bibcode:2021MinM...85..291W. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.43. S2CID 235729616.

- ^ Mineralienatlas

- ^ Anthony, John W.; Bideaux, Richard A.; Bladh, Kenneth W.; Nichols, Monte C. (2005). "Cassiterite" (PDF). Handbook of Mineralogy. Mineral Data Publishing. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "Cassiterite". Mindat.org.

- ^ Webmineral

- ^ Hurlbut, Cornelius S.; Klein, Cornelis (1985). Manual of Mineralogy (20th ed.). New York: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 306–307. ISBN 0-471-80580-7.

- ^ Watt, Louise (2008-11-01). "Mining for minerals fuels Congo conflict". Yahoo! News. Yahoo! Inc. Associated Press. Retrieved 2009-09-03.

- ^ Polgreen, Lydia (2008-11-16). "Congo's Riches, Looted by Renegade Troops". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ^ a b "Defininiton of κασσίτερος". logeion.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2024-11-07.

- ^ "Homer, Iliad, Book 18, line 590". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2024-11-07.

- ^ "ToposText". topostext.org. Retrieved 2024-11-07.

- ^ Læssøe, Jørgen (1970-01-01). "Akkadian annakum: "tin" or "lead"?". Acta Orientalia. 24: 10. doi:10.5617/ao.5285. ISSN 1600-0439.

- ^ Dossin, G. (1970). "La Route De L'étain En Mésopotamie Au Temps De Zimri-Lim". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 64 (2): 97–106. ISSN 0373-6032. JSTOR 23283408.

- ^ Muhly, James D. (1985-04-01). "Sources of Tin and the Beginnings of Bronze Metallurgy". American Journal of Archaeology. 89 (2): 275–291. doi:10.2307/504330. ISSN 0002-9114. JSTOR 504330.

- ^ CLASSICS, FACULTY OF (2021). CAMBRIDGE GREEK LEXICON. CAMBRIDGE University Press. pp. 746–7. ISBN 978-0-521-82680-8.

- ^ a b STEPHANUS BYZANTIUS Margarethe Billerbeck] Stephani Byzantii Ethnica, K O. BY MARGARETHE BILLERBECK. 2014. pp. 56–7.

- ^ "ToposText". topostext.org. Retrieved 2024-11-07.

External links

[edit]Cassiterite

View on GrokipediaMineralogical Properties

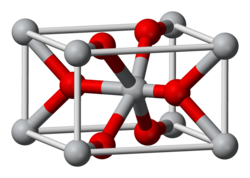

Chemical Composition and Crystal Structure

Cassiterite has the chemical formula SnO₂, corresponding to tin(IV) oxide, in which tin adopts the +4 oxidation state.[7] This composition reflects a stoichiometric ratio of one tin atom to two oxygen atoms, with natural specimens often containing minor impurities such as iron, niobium, tantalum, or silicon substituting for tin or incorporating as lattice defects, which influence color variations from colorless to black or brown.[7][8] The mineral crystallizes in the tetragonal crystal system as a member of the rutile group, with space group P4₂/mnm (No. 136).[7] In this structure, tin cations occupy octahedral sites coordinated by six oxygen anions, forming a three-dimensional framework analogous to rutile (TiO₂), with unit cell parameters a ≈ 4.738 Å and c ≈ 3.187 Å.[9] Common crystal habits include prismatic, dipyramidal, and botryoidal aggregates, often exhibiting twinning on {011} planes as contact or penetration twins, which can produce geniculated or repeated forms.[7][3] These structural features contribute to cassiterite's physical properties, including a density of 6.8–7.1 g/cm³, primarily due to the high atomic mass of tin (118.71 u), and a Mohs hardness of 6–7, which enhances its durability against chemical weathering.[2][10]Physical, Optical, and Gemological Characteristics

Cassiterite displays an adamantine to sub-metallic luster, often appearing greasy on fracture surfaces.[3] Its Mohs hardness measures 6 to 7, rendering it moderately resistant to scratching, while its specific gravity ranges from 6.98 to 7.01, among the highest for nonmetallic minerals.[3] The mineral typically occurs as opaque brown to black masses due to impurities, though rare transparent varieties exhibit colorless, yellow, or pale brown hues.[2] It produces a white to pale gray streak and features a subconchoidal fracture with imperfect cleavage on {100}.[7] Optically, cassiterite is uniaxial positive, with refractive indices of nω = 1.990–2.010 and nε = 2.093–2.100, values exceeding those of diamond and contributing to exceptional light bending.[11] This high refractive index, coupled with strong dispersion (0.071), enables faceted stones to exhibit vivid fire through spectral separation.[12] Birefringence falls between 0.096 and 0.098, with pleochroism generally absent or weak.[12] As a gem material, cassiterite holds niche value for its brilliance and durability in protected settings, though its brittleness restricts everyday jewelry use.[12] Cuttable, transparent crystals remain scarce, chiefly from Bolivian and Russian localities, where they command collector interest for dispersive effects surpassing many common gems.[13] Spectral features, including absorption bands tied to Sn-O vibrations, aid identification via infrared or Raman analysis.[11]Geological Occurrence and Formation

Genetic Processes

Cassiterite forms primarily through late-stage magmatic differentiation processes in peraluminous granitic magmas, where tin enrichment occurs in residual melts, leading to its concentration in pegmatites, greisens, or aplites. These magmas, typically high in silica and derived from crustal melting of sedimentary protoliths, exhibit S-type characteristics that favor volatile-rich, tin-bearing phases during fractional crystallization.[14] Tin mobilization begins with the partitioning of Sn into the melt during early magmatic stages, followed by exsolution of hydrothermal fluids as the magma cools and crystallizes, transitioning from orthomagmatic to hydrothermal conditions.[15] In hydrothermal systems, cassiterite precipitates from Sn(IV)-complexed fluids, often at temperatures of 300–500 °C, driven by mechanisms such as fluid cooling, mixing with meteoric water, or changes in pH and oxidation state that reduce Sn solubility.[16] These fluids, exsolved from the crystallizing granite, carry tin as chloride or fluoride complexes and deposit cassiterite in veins or disseminated forms, commonly associated with minerals like tourmaline, topaz, quartz, and sulfides such as pyrrhotite or chalcopyrite due to coeval precipitation under reducing to oxidizing conditions.[17] Secondary enrichment can occur via hydrothermal alteration of primary deposits, where remobilization and redeposition enhance tin grades in altered zones.[18] Placer deposits form through the mechanical erosion and transport of primary cassiterite-bearing veins, with the mineral's high density (6.8–7.1 g/cm³) and chemical durability enabling concentration in alluvial settings where hydraulic sorting separates it from lighter gangue.[19] Cassiterite's resistance to breakdown stems from its low solubility in neutral to acidic surface waters, as SnO₂ remains stable under typical weathering conditions, preventing significant dissolution and allowing accumulation over geological timescales.[20] This durability contrasts with more reactive silicates in host rocks, facilitating economic secondary deposits via supergene processes.[21]Principal Deposits and Global Distribution

Cassiterite deposits are predominantly associated with late-stage granitic intrusions, occurring in hydrothermal veins, greisens, and pegmatites, as seen in historical European districts such as Cornwall in the United Kingdom and the Erzgebirge (Ore Mountains) along the Germany-Czech Republic border. In Cornwall, cassiterite formed in quartz-cassiterite-tourmaline veins cutting granite and surrounding country rocks, contributing significantly to pre-20th century global tin supply.[22] The Erzgebirge features similar vein systems with cassiterite alongside sulfides like arsenopyrite, supporting long-term mining since medieval times.[22] Placer deposits, derived from the weathering and fluvial transport of primary cassiterite due to its high specific gravity (6.8–7.1), dominate in Southeast Asia and North America. The Bangka-Belitung Islands of Indonesia host extensive offshore and onshore placers, where cassiterite concentrates in heavy mineral sands, accounting for a substantial portion of the country's output.[23] In Alaska, USA, placer occurrences along streams like Cassiterite Creek near the Lost River Mine yield detrital grains from eroded granitic sources.[24] Contemporary production centers on Asia, with China leading via deposits in Yunnan and Guangxi provinces, where cassiterite occurs in skarn and vein systems; Indonesia follows with placer-dominated output; and Myanmar contributes from vein and placer sources in its Shan State and Wa regions. According to USGS data for 2023, global mine production reached 296,000 metric tons of tin content, with China at 75,000 metric tons (estimated), Indonesia at 75,000 metric tons, and Myanmar at 44,000 metric tons, nearly all derived from cassiterite ores.[25] In Africa, the Democratic Republic of Congo's Bisie Mine, operated by Alphamin Resources, achieved record production of 17,323 metric tons of contained tin in 2024 from high-grade underground vein deposits exceeding 3% tin grade.[26] [27] World tin reserves stand at 4,700,000 metric tons, concentrated in countries like Indonesia (800,000 metric tons), Brazil (490,000 metric tons), and China (170,000 metric tons), with cassiterite comprising over 95% of primary tin resources globally.[25] These endowments underscore cassiterite's role in supplying tin for alloys and electronics, though extraction challenges in remote or conflict-prone areas affect distribution dynamics.[25]