Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

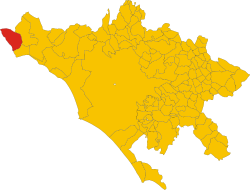

Civitavecchia

View on WikipediaCivitavecchia (Italian: [ˌtʃivitaˈvɛkkja], meaning "ancient town") is a city and major sea port on the Tyrrhenian Sea 60 kilometres (37 miles) west-northwest of Rome. Its legal status is a comune (municipality) of Rome, Lazio.

Key Information

The harbour is formed by two piers and a breakwater on which stands a lighthouse.

History

[edit]

Etruscan era

[edit]The whole territory of Civitavecchia is dotted with the remains of Etruscan tombs and it is likely that in the centre of the current city a small Etruscan settlement thrived. The Etruscan necropolis of Mattonara, not far from the Molinari factory, is almost certainly from the 7th - 6th century BC and was most likely connected with the nearby necropolis of Scaglia. An ancient port formed by small parallel basins capable of accommodating single vessels was still visible at the end of the 19th century near Forte Michelangelo.

An Etruscan settlement on the hill of Ficoncella can still be seen. The first baths of the settlement were built there before 70 BC, and known by the Romans as Aquae Tauri.

Roman era

[edit]The nearby monumental baths at Terme Taurine were built originally in the Roman Republican era, possibly by Titus Statilius Taurus, prefect of Rome.

The harbour was greatly enlarged by the Emperor Trajan at the beginning of the 2nd century and became known as Centum Cellae, probably due to the many vaulted "cells" forming the harbour wall, some of which can still be seen. The first occurrence of the name Centum Cellae is from a letter by Pliny the Younger[3] in AD 107. It has been suggested that the name could instead refer to the centum ("hundred") halls of the extensive villa of Trajan which was nearby.[4] The harbour was probably built by Trajan's favourite architect, Apollodorus of Damascus (who also built the harbour of Ancona). The town was also known as Centum Cellae and was developed from the same time. Trajan's sumptuous villa pulcherrima (most beautiful, according to Pliny[3]) must have been built at the same time but traces have yet to be found, although the Terme Taurine baths and the large cistern nearby are likely to have been included.[5] Pliny was summoned by Trajan to his villa there for an exceptional meeting there of the consilium principis (advisory council) which normally took place in Rome, and which indicates the status of the villa as an imperial residence. The villa was also used later by the young Marcus Aurelius, probably in the years 140-145[6] who built a vivarium there and also in 173 by Commodus.[7]

Inscriptions from between the 2nd and 3rd centuries from a cemetery near the Roman harbour prove the presence of classiari, sailors from the navy, and also of a noble class. They also tell of the number and type of ships which were detachments of the fleets of Ravenna and of Misenum.[8]

In 251 Pope Cornelius was imprisoned in Centumcellae during the persecutions of Decius and his successor Trebonianus Gallus and died there in 253.

In the 4th and 5th centuries the city and port became even more prosperous and busy, as Rutilius Namatianus described it in 414[9] as it became an important port of Rome due to the silting of Ostia.

In the 530s, Centumcellae was a Byzantine stronghold and until 553 the city suffered in the wars between the Goths and the Byzantines.[10][11][12]

Later history

[edit]It became part of the Papal States in 728 and Pope Gregory III refortified Centumcellae. As the port was raided by the Saracens in 813–814, 828, 846 and finally in 876, a new settlement in a more secure place was therefore built by order of Pope Leo IV as soon as 854.[13] In the meantime, however, the inhabitants returned to the old town by the shore in 889 and rebuilt it, giving it the name Civitas Vetus.[4] The Popes gave the settlement as a fief to several local lords, including the Count Ranieri of Civitacastellana and the Abbey of Farfa, and the Di Vico, who held Centumcellae in 1431. In that year, pope Eugene IV sent an army under cardinal Giovanni Vitelleschi and several condottieri (Niccolò Fortebraccio, Ranuccio Farnese and Menicuccio dell'Aquila among them) to recapture the place, which, after the payment of 4,000 florins, became thenceforth a full Papal possession, led by a vicar and a treasurer.

The place became a free port under Pope Innocent XII in 1696 and by the modern era was the main port of Rome. The French Empire occupied it in 1806.

The French novelist Stendhal served as consul for a time in Civitavecchia.

On 16 April 1859 the Rome and Civitavecchia railway was opened for service.

The Papal troops opened the gates of the fortress to the Italian general Nino Bixio in 1870. This permanently removed the port from papal control.

During World War II, the Allies launched several bombing raids against Civitavecchia, which damaged the city and inflicted several civilian casualties.[14] On June 27, 1944, two American soldiers from the 379th Port Battalion, Fred A. McMurray and Louis Till, allegedly raped two Italian women in Civitavecchia and murdered a third. McMurray and Till were subsequently both executed by the United States Army by hanging five months later.[15]

Economy

[edit]Civitavecchia is today a major cruise and ferry port, the main starting point for sea connection from central Italy to Sardinia, Sicily, Tunis and Barcelona. Fishing has a secondary importance.

The city is also the seat of two thermal power stations. The conversion of one of them to coal has raised the population's protests, as it is feared it could create heavy pollution.

Main sights

[edit]

Roman city

[edit]The modern inner harbour (darsena) rests on ancient foundations many of which can be seen and whose shape is still very much the same as it was in Trajan's time. It had a curved breakwater on the southern side and a straight one to the north with arches to reduce the waves which still exist.

The Torre di Lazzaretto is the only remaining Tower of four large Roman round towers that served as beacons around the ancient harbour. Remains of warehouses can be seen between the large basin and the inner harbour (darsena), still used during the Middle Ages.

A section of the Via Aurelia running along the harbour, 6 m wide and at a depth of 3 m, was excavated. Some of the Roman city wall is visible in the basement of the Fraternity of the Banner in the Piazza Leandra. Remains of an aqueduct and a large cistern, possibly part of Trajan's villa, are preserved.[16]

North of the city at Ficoncella are the Terme Taurine baths frequented by Romans and still popular with the Civitavecchiesi. The modern name stems from the common fig plants among the various pools.

Also at Ficoncella nearby are the baths of Aquae Tauri from the earlier Etruscan and early Roman settlement.[17] A larger building of 160x100 m enclosed the baths and is being excavated.[18]

Other sights

[edit]The massive Forte Michelangelo was first commissioned from Donato Bramante by Pope Julius II, to defend the port of Rome. The upper part of the "maschio" tower, however, was designed by Michelangelo, whose name is generally applied to the fortress. Pius IV added a convict prison, and the arsenal, designed by Bernini, was built by Alexander VII.[4]

Major cruise lines start and end their cruises at this location, and others stop for shore excursion days to visit Rome and the Vatican, ninety minutes away.

Geography

[edit]Climate

[edit]Civitavecchia experiences a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csa).

| Climate data for Civitavecchia (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1945–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.3 (64.9) |

22.2 (72.0) |

22.8 (73.0) |

25.4 (77.7) |

30.6 (87.1) |

34.2 (93.6) |

35.2 (95.4) |

37.9 (100.2) |

33.0 (91.4) |

27.6 (81.7) |

26.6 (79.9) |

20.8 (69.4) |

37.9 (100.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 13.5 (56.3) |

13.8 (56.8) |

15.5 (59.9) |

17.8 (64.0) |

21.7 (71.1) |

25.4 (77.7) |

28.0 (82.4) |

28.6 (83.5) |

25.4 (77.7) |

22.0 (71.6) |

18.2 (64.8) |

14.7 (58.5) |

20.4 (68.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.4 (50.7) |

10.5 (50.9) |

12.3 (54.1) |

14.7 (58.5) |

18.3 (64.9) |

22.2 (72.0) |

24.7 (76.5) |

25.3 (77.5) |

22.2 (72.0) |

19.0 (66.2) |

15.2 (59.4) |

11.6 (52.9) |

17.2 (63.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 7.5 (45.5) |

7.3 (45.1) |

9.0 (48.2) |

11.5 (52.7) |

15.1 (59.2) |

18.8 (65.8) |

21.4 (70.5) |

21.9 (71.4) |

18.9 (66.0) |

15.9 (60.6) |

12.2 (54.0) |

8.6 (47.5) |

14.0 (57.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −4.4 (24.1) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

1.6 (34.9) |

5.3 (41.5) |

10.2 (50.4) |

14.0 (57.2) |

13.0 (55.4) |

10.4 (50.7) |

5.8 (42.4) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 66.4 (2.61) |

63.3 (2.49) |

73.2 (2.88) |

57.9 (2.28) |

43.9 (1.73) |

27.5 (1.08) |

13.6 (0.54) |

17.5 (0.69) |

72.6 (2.86) |

113.7 (4.48) |

116.5 (4.59) |

93.1 (3.67) |

759.1 (29.89) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 6.9 | 6.1 | 6.0 | 6.2 | 5.0 | 2.8 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 4.6 | 6.8 | 9.0 | 7.8 | 64.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 73.7 | 73.1 | 74.9 | 75.4 | 75.1 | 74.7 | 73.3 | 73.4 | 73.4 | 73.4 | 75.9 | 72.6 | 74.2 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | 6.2 (43.2) |

6.1 (43.0) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.7 (51.3) |

14.3 (57.7) |

18.0 (64.4) |

20.1 (68.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

17.4 (63.3) |

14.9 (58.8) |

11.1 (52.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

12.9 (55.2) |

| Source 1: NOAA[19] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Temperature estreme in Toscana (extremes)[20] | |||||||||||||

Transport

[edit]

The Port of Civitavecchia, also known as "Port of Rome",[21] is an important hub for the maritime transport in Italy, for goods and passengers. Part of the "Motorways of the Sea",[22] it is linked to several Mediterranean ports and represents one of the main links between Italian mainland to Sardinia.

Civitavecchia railway station, opened in 1859, is the western terminus of the Rome–Civitavecchia railway, which forms part of the Pisa–Livorno–Rome railway. A short line linking the town center to the harbour survived until the early 2000s.[23] It counted two stations: Civitavecchia Marittima, serving the port, and Civitavecchia Viale della Vittoria.

Civitavecchia is served by the A12, an unconnected motorway linking Rome to Genoa and by the State highway SS1 Via Aurelia, which also links the two stretches. The town is also interested by a project regarding a new motorway, the Civitavecchia-Venice or New Romea,[24] nowadays completed as a dual carriageway between Viterbo and Ravenna (via Terni, Perugia and Cesena) and commonly known in Italy as the Orte-Ravenna.

Education

[edit]The commune has multiple preschools,[25] primary schools,[26] junior high schools,[27] and high schools.[28] Polo Universitario di Civitavecchia is located in the city.

Twin towns and sister cities

[edit]Civitavecchia is twinned with:

Amelia, Italy

Amelia, Italy Bethlehem, Palestinian Authority, since 2000[29][30][31]

Bethlehem, Palestinian Authority, since 2000[29][30][31] Ishinomaki, Japan

Ishinomaki, Japan Nantong, China

Nantong, China

People

[edit]- Manuele Blasi (b. 1980), football player

- Silvio Branco (b. 1966), professional boxer

- Andrea Casali (1705–1784), Rococo painter

- Alessio De Sio (1968), journalist, city mayor from 2001 to 2005, director of communication of "Hitachi" Rail Italy ex "AnsaldoBreda"

- Raffaele Giammaria (b. 1977), racing driver

- Marco Mocci (b. 1982), racing driver

- Pasquale Lattanzi (b. 1950), former football player

- Oscar Lini (1928-2016), football player

- Ermanno Palmieri (1921-1982), football player

- Giancarlo Peris (b. 1941), former track athlete

- Roberto Petito (b. 1971), road bicycle racer

- Giulio Saraudi (1938–2005), boxer

- Eugenio Scalfari (b. 1924), journalist, founder of la Repubblica

- Emiliano Sciarra (b. 1971), game designer[32]

- Roldano Simeoni (b. 1948), former water polo player

- Vittorio Tamagnini (1910–1981), boxer

See also

[edit]- Arsenal of Civitavecchia

- Civitavecchia Calcio

- Civitavecchia di Arpino

- Civitavecchia, Cachar district, Assam, India (spelt as "Chibita Bichia" by the locals).

References

[edit]- ^ "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Italian National Institute of Statistics. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ "Popolazione Residente al 1° Gennaio 2018". Italian National Institute of Statistics. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ a b Pliny Epist. 6.31

- ^ a b c One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Civita Vecchia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 416–417.

- ^ Anna Maria Reggiani, la villa pulcherrima di traiano a CENTUMCELLAE, doi: 10.1387/veleia.19438 Veleia, 35, 129-149, 2018

- ^ Fronto, Epist. ad M. Caesarem 3.21.1

- ^ Historia Augusta, life of Commodus, 1.9

- ^ "Hidden Treasures in the Darsena Romana in the Port of Civitavecchia". Port Mobility Civitavecchia. February 3, 2016.

- ^ Rutilius Namatianus, A Voyage Home to Gaul 217‑276

- ^ Procopius, De Bello Gothico VI, VII

- ^ Procopius, De Bello Gothico VIII.33‑35

- ^ Procopius, De Bello Gothico III.36‑40

- ^ "Saint Leo IV". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ "History of Civitavecchia | Port of Rome – Civitavecchia".

- ^ "Emmett Till, His Father, and the Scars on America's Soul". Esquire. October 19, 2016.

- ^ "Topographical dictionary - Centumcellae - Civitavecchia - Cistern and aqueduct". www.ostia-antica.org.

- ^ F. Stasolla et al., Nuove ricerche nel territorio di Civitavecchia. Un progetto per Aquae Tauri, in Scienze dell'Antichità 24.1 (2018), pp. 149-174.

- ^ "Aquae Tauri, the Achelous project | Roman ports". www.romanports.org.

- ^ "Civitavecchia Climate Normals 1991–2020". World Meteorological Organization Climatological Standard Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 27 August 2023. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ^ "Civitavecchia Santa Marinella" (in Italian). Temperature estreme in Toscana. Retrieved 8 December 2024.

- ^ "Il porto di Civitavecchia - Port-of-rome.org". www.port-of-rome.org.

- ^ "Infos at R.A.M. website (search the list of ports)". Archived from the original on April 19, 2011.

- ^ "Civitavecchia Marittima". www.ilmondodeitreni.it.

- ^ (in Italian) Article at ANAS website

- ^ "Scuole dell'Infanzia Archived 2014-12-21 at the Wayback Machine." Commune of Civitavecchia. Retrieved on December 21, 2014.

- ^ "Scuole elementari Archived 2014-12-21 at the Wayback Machine." Commune of Civitavecchia. Retrieved on December 21, 2014.

- ^ "Scuola media inferiore Archived 2014-12-21 at the Wayback Machine." Commune of Civitavecchia. Retrieved on December 21, 2014.

- ^ "Scuole medie superiori Archived 2014-12-21 at the Wayback Machine." Commune of Civitavecchia. Retrieved on December 21, 2014.

- ^ "Twinning with Palestine". The Britain - Palestine Twinning Network. Archived from the original on 2012-06-28. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- ^ The City of Bethlehem has signed a twinning agreements with the following cities Bethlehem Municipality.

- ^ "::Bethlehem Municipality::". www.bethlehem-city.org. Archived from the original on 2010-07-24. Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- ^ "Emiliano Sciarra | Board Game Designer | BoardGameGeek".

External links

[edit]Civitavecchia

View on GrokipediaGeography

Location and physical features

Civitavecchia is situated on the Tyrrhenian Sea coast in central Italy, within the Lazio region and the Metropolitan City of Rome. The city lies approximately 72 kilometers northwest of Rome as measured by road distance.[7] Its geographical coordinates are 42°05′N 11°48′E.[8] The comune encompasses a total area of 73.74 square kilometers. Elevations in the urban area average around 20 meters above sea level, with the terrain primarily consisting of low-lying coastal plains that facilitate maritime access and port infrastructure.[9] To the north and east, the city is bordered by the Tolfa Mountains, a low volcanic range rising to several hundred meters, which demarcates the transition from coastal flats to inland hills and influences local drainage and land use patterns.[10] The urban layout features concentrated industrial and port-related zones along the waterfront, extending into residential and commercial districts on slightly elevated inland terrain.[11]Climate and environment

Civitavecchia features a Mediterranean climate (Köppen Csa) with mild winters and hot, dry summers. Average annual temperatures range from lows of about 6°C (43°F) in January to highs of 29°C (84°F) in August, yielding an overall yearly average of approximately 16°C (61°F). Precipitation averages 663 mm annually, primarily falling between October and March, with November recording the highest monthly total of around 91 mm (3.6 inches). These metrics derive from historical observations at local weather stations, reflecting the region's coastal influence moderating extremes.[12][13]| Month | Avg High (°C) | Avg Low (°C) | Precipitation (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | 12 | 6 | 80 |

| February | 12 | 6 | 77 |

| March | 15 | 8 | 60 |

| April | 17 | 10 | 50 |

| May | 21 | 13 | 37 |

| June | 25 | 17 | 23 |

| July | 28 | 19 | 13 |

| August | 29 | 19 | 23 |

| September | 25 | 16 | 60 |

| October | 21 | 13 | 100 |

| November | 16 | 10 | 113 |

| December | 13 | 7 | 67 |

History

Ancient origins

Archaeological evidence indicates prehistoric and protohistoric habitation in the Civitavecchia area, particularly at the Mattonara site, where settlements, necropolises, and production zones for sea salt extraction have been identified, reflecting early exploitation of coastal resources.[20] During the Iron Age, populations shifted from inland Protovillanovian hilltop sites to coastal locations, likely driven by access to marine resources and natural harbors conducive to basic maritime activities.[20] Etruscan settlements emerged by the late 9th century BCE, as evidenced by the Necropolis of La Scaglia, which contains over 70 tombs spanning the Villanovan (proto-Etruscan) phase through the archaic period to the 6th century BCE.[21][20] These include rock-cut chamber tombs with dromoi, double-sloping ceilings, and burial beds, alongside a nearby archaic Etruscan necropolis at Mattonara dating to the 7th–6th centuries BCE.[20] Associated settlements, such as Castellina del Marangone, yielded bucchero pottery—including 7th-century BCE goblets and 6th-century BCE vessels with figural motifs—signifying organized communities with ceramic production capabilities.[22] Trade artifacts, such as Egyptian-inspired balsamaria from the 6th century BCE and rare Mycenaean ceramics from nearby Luni sul Mignone, point to limited but verifiable external exchanges, facilitated by the region's promontory position and proximity to trade routes.[22] Excavations provide scant data on population sizes or daily life, with necropolises offering the primary proxy for community scale, but they confirm a transition to proto-urban coastal centers reliant on local resources like salt and early seafaring.[20][22]Roman development

Centumcellae was founded by Emperor Trajan in the early 2nd century AD as a strategic harbor, deriving its name from the Latin centum cellae, referring to its numerous warehouses designed for storage.[23] The settlement emerged as part of Trajan's broader infrastructure initiatives, including the Aqua Traiana aqueduct inaugurated in 109 AD, which channeled water from Lake Bracciano sources to support regional development, though primarily directed toward Rome. Archaeological traces, such as pilae and concrete foundations, indicate sophisticated harbor construction with breakwaters extending approximately 400 meters apart and an artificial island about 500 meters offshore, exemplifying Roman coastal engineering to create sheltered anchorage.[24] The port functioned primarily as a naval base, serving as a secondary hub for the Classis Misenensis (fleet of Misenum) and Classis Ravennatis (fleet of Ravenna), facilitating military logistics and fleet maintenance amid Rome's Mediterranean operations.[25] Warehouses and quays supported the handling of goods, including provisions for imperial supply chains, though epigraphic and ceramic evidence shows limited direct involvement in bulk grain imports to Rome compared to Ostia or Portus, with a focus on regional trade and naval provisioning.[26] Ruins of these structures, alongside inscriptions attesting to imperial oversight, underscore its integration into the empire's maritime network for both commercial storage and defense.[27] By the mid-2nd century, under Hadrian and successors, Centumcellae experienced growth tied to imperial stability, with visible remnants like the arched breakwater at Molo del Lazzaretto—standing 3-3.5 meters in water depth—demonstrating enduring engineering resilience.[28] However, from the 3rd century onward, the settlement declined amid the Crisis of the Third Century, marked by barbarian incursions, naval reductions, and economic contraction; reduced coin hoards and structural abandonments in the region reflect broader disruptions to Roman coastal defenses and trade routes.[29]Medieval and early modern periods

Following the decline of the Roman port of Centumcellae after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the area faced repeated incursions by Saracen pirates during the 8th and 9th centuries, which contributed to the destruction of coastal infrastructure and prompted a temporary inland relocation of inhabitants for safety.[23] By the 11th century, reconstruction efforts under papal authority revived the settlement, renaming it Civitavecchia and integrating it into the Papal States as a fortified harbor and naval outpost to support ecclesiastical territorial control.[23] Throughout the medieval period, Civitavecchia functioned primarily as a defensive and logistical hub for the Papal States, with its port facilitating limited maritime activities amid ongoing threats from piracy. The papacy leveraged the location for maintaining a modest naval presence to protect papal shipping routes and counter coastal raiders. Economic activity centered on basic trade, including salt extraction and transport from nearby salterns, which provided revenue and provisions for papal forces, though the site's growth remained constrained by insecurity and sparse documentation of commercial volumes.[30] In the early modern era, escalating Barbary pirate threats necessitated enhanced fortifications; Pope Julius II commissioned the initial Forte Michelangelo in 1508, designed by Donato Bramante to safeguard the harbor, with Michelangelo Buonarroti later advising on bastion reinforcements for improved artillery positioning, completing the structure by 1537.[31][32] Further defenses followed under Pope Urban VIII, who in 1630 ordered extensive city walls to encircle the port and separate it from urban areas, enabling better containment of potential invasions and enhancing the site's role in papal naval operations against Ottoman-allied corsairs.[33] Population stability was disrupted by recurrent epidemics, notably the 1656–1657 plague outbreak originating from Naples and spreading through Lazio ports, which severely impacted Civitavecchia's demographics alongside Rome, though precise local mortality figures remain undocumented amid regional estimates of high fatalities from bubonic plague strains.[34] These events, combined with defensive priorities, kept Civitavecchia's early modern population modest, hovering around a few thousand, focused on maritime defense rather than expansive growth.[35]19th and 20th centuries

During the early 19th century, Civitavecchia served as the principal port of the Papal States, with expansions focused on enhancing its role in trade and defense amid declining papal naval power. Pope Pius IX oversaw the completion of the Rome-Civitavecchia railway in 1859, Italy's first domestically produced rail line, which connected the port directly to the capital and increased cargo throughput by linking inland markets to maritime routes.[36] This infrastructure upgrade, spanning approximately 80 kilometers, reduced transport times for goods like grain and alum exports, which constituted a major revenue source for the papacy, though papal customs duties limited broader commercial growth.[37] The port's integration into the Kingdom of Italy occurred on September 6, 1870, when papal forces surrendered without combat to General Nino Bixio's expeditionary troops, ending centuries of Vatican control and aligning Civitavecchia with national unification efforts.[36] Post-annexation, the elimination of internal tariffs and enhanced rail connectivity spurred trade volumes, positioning the port as Rome's primary gateway for imports of coal, timber, and industrial materials essential to Italy's emerging economy; annual tonnage handled rose steadily in the decades following, reflecting causal links between political consolidation and logistical efficiencies.[36] Under the fascist regime from 1922 to 1943, Civitavecchia experienced limited port enhancements as part of Mussolini's "Battle for Grain" and maritime autarky policies, including minor dredging and warehouse additions to support grain imports and naval logistics, though these yielded modest output gains compared to pre-fascist rail-enabled expansions due to resource diversion toward military preparations.[38] During World War II, the port faced intensive Allied bombing campaigns from late 1943 through 1944, targeting Axis supply lines; these raids, combined with German demolitions, inflicted severe structural damage on docks, cranes, and warehouses, rendering much of the harbor inoperable.[39] U.S. Fifth Army units captured the intact town on June 7, 1944, during a rapid 40-mile advance northwest from liberated Rome, bypassing amphibious operations as ground forces exploited German retreats along the Tyrrhenian coast.[40][41]Post-World War II to present

Following the extensive damage from Allied bombing campaigns during World War II, which destroyed much of the city and port infrastructure, reconstruction in Civitavecchia commenced rapidly after 1945. Efforts prioritized restoring urban and maritime facilities, with Italy's broader post-war recovery bolstered by the Marshall Plan, which allocated approximately 74% of its aid to public infrastructure rebuilding, including ports essential for economic resumption.[42][43] The port's expansion during this phase exceeded pre-war boundaries, incorporating more robust moles and docks to accommodate increasing commercial activity.[44] Through the 1950s and 1960s, the port evolved as a vital node for cargo handling and ferry services, particularly linking mainland Italy to Sardinia and Sicily, driven by the geographic imperative of island-mainland connectivity and post-war economic integration. By the 1970s, it had solidified as a primary hub for regional maritime transport, with ferry routes facilitating essential passenger and goods movement amid Italy's industrialization.[36] This period marked a shift toward diversified traffic, laying groundwork for later passenger growth. In the 21st century, expansions such as waterfront redevelopment projects integrating historic areas like the Darsena Romana have enhanced capacity, positioning Civitavecchia as Italy's leading cruise and ferry port. Passenger volumes surged, exceeding 3 million annually by 2023—primarily from ferries to Sardinia and Sicily alongside cruises—with a record 3.46 million in 2024, reflecting tourism recovery and sustained regional links.[45][46][47] Total cargo throughput reached 9.57 million tons in 2023, underscoring the port's role in Mediterranean trade networks sustained by ferry-dominated routes to islands.[48]Demographics and society

Population trends

As of December 31, 2023, Civitavecchia's resident population numbered 51,697, reflecting a slight annual decline from 51,722 in 2022.[49] This follows a period of relative stability since the early 2000s, with the population peaking near 52,000 around 2010 before modest fluctuations; for example, it stood at 52,069 in 2020 and 51,880 in 2021 per census updates.[49] Post-World War II censuses indicate growth from approximately 36,000 in 1961 to over 50,000 by 1981, driven by industrial and port-related opportunities, though exact 1950s figures hover around 28,000-30,000 based on national series adjustments.[50] The municipality exhibits an aging demographic profile, with a 2023 natural balance showing 282 births against 564 deaths, yielding a deficit of 282 individuals.[51] Local fertility trends lag below the national rate of 1.18 children per woman in 2024, contributing to low birth rates of about 5.5 per 1,000 inhabitants.[52] Positive net migration of +257 in 2023—1,014 arrivals minus 757 departures—partially offsets natural decline, maintaining overall stagnation rather than sharp contraction.[51] Over a municipal area of 74.49 km², this translates to a density of roughly 694 inhabitants per km², with patterns suggesting contained urban core concentration alongside limited suburban sprawl.[3]| Year | Population (Dec 31) |

|---|---|

| 2020 | 52,069 |

| 2021 | 51,880 |

| 2022 | 51,722 |

| 2023 | 51,697 |