Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Romanians

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Romanians |

|---|

|

Romanians (Romanian: români, pronounced [roˈmɨnʲ]; dated exonym Vlachs) are a Romance-speaking[63][64][65] ethnic group and nation native to Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe.[66] Romanians share a common culture, history, ancestry and language and live primarily in Romania and Moldova. There is a debate regarding the ethnic categorisation of the Moldovans, concerning whether they constitute a subgroup of the Romanians or a completely different ethnic group. The origin of the Romanians is also fiercely debated, one theory suggests that the ancestors of Romanians are the Daco-Romans, while the other theory suggests that Romanians are mainly the Thraco-Romans and Illyro-Romans from the inner balkans, who later migrated north of the Danube.

In one interpretation of the 1989 census results in Moldova, the majority of Moldovans were counted as ethnic Romanians as well.[67][68] Romanians also form an ethnic minority in several nearby countries situated in Central, Southeastern, and Eastern Europe, most notably in Hungary, Serbia (including Timok), and Ukraine.

Estimates of the number of Romanian people worldwide vary from 24 to 30 million, in part depending on whether the definition of the term "Romanian" includes natives of both Romania and Moldova, their respective diasporas, and native speakers of both Romanian and other Eastern Romance languages. Other speakers of the latter languages are the Aromanians, the Megleno-Romanians, and the Istro-Romanians (native to Istria), all of them unevenly distributed throughout the Balkan Peninsula, which may be considered either Romanian subgroups or separated but related ethnicities.

History

[edit]Antiquity

[edit]

The territories of modern-day Romania and Moldova were inhabited by the ancient Getae and Dacian tribes. King Burebista who reigned from 82/61 BC to 45/44 BC, was the first king who successfully unified the tribes of the Dacian kingdom, which comprised the area located between the Danube, Tisza, and Dniester rivers. King Decebalus who reigned from 87 to 106 AD was the last king of the Dacian kingdom before it was conquered by the Roman Empire in 106,[69] after two wars between Decebalus' army and Trajan's army. Prior to the two wars, Decebalus defeated a Roman invasion during the reign of Domitian between 86 and 88 AD.[70]

The Roman administration retreated from Dacia between 271 and 275 AD, during the reign of emperor Aurelian under the pressure of the Goths and the Dacian Carpi tribe. The later Roman province Dacia Aureliana, was organized inside former Moesia Superior.[71] It was reorganized as Dacia Ripensis (as a military province, devastated by an Avars invasion in 586) [72] and Dacia Mediterranea (as a civil province, devastated by an Avar invasion in 602).

The Diocese of Dacia (circa 337–602) was a diocese of the later Roman Empire, in the area of modern-day Balkans.[73] The Diocese of Dacia was composed of five provinces, the northernmost provinces were Dacia Ripensis (the Danubian portion of Dacia Aureliana, one of the cities of Dacia Ripensis in today Romania is Sucidava) and Moesia Prima (today in Serbia, near the border between Romania and Serbia).[74] The territory of the diocese was devastated by the Huns in the middle of 5th century and finally overrun by the Avars and Slavs in late 6th and early 7th century.[75]

Scythia Minor (c. 290 – c. 680) was a Roman province corresponding to the lands between the Danube and the Black Sea, today's Dobruja divided between Romania and Bulgaria.[76][77] The capital of the province was Tomis (today Constanța).[76] According to the Laterculus Veronensis of c. 314 and the Notitia Dignitatum of c. 400, Scythia belonged to the Diocese of Thrace.[78] The indigenous population of Scythia Minor was Dacian and their material culture is apparent archaeologically into the sixth century.[76] Roman fortifications mostly date to the Tetrarchy or the Constantinian dynasty. The province ceased to exist around 679–681, when the region was overrun by the Bulgars, which the Emperor Constantine IV was forced to recognize in 681.[79]

Early Middle Ages to Late Middle Ages

[edit]During the Middle Ages Romanians were mostly known as Vlachs, a blanket term ultimately of Germanic origin, from the word Walha, used by ancient Germanic peoples to refer to Romance-speaking and Celtic neighbours. Besides the separation of some groups (Aromanians, Megleno-Romanians, and Istro-Romanians) during the Age of Migration, many Vlachs could be found all over the Balkans, in Transylvania,[80] across Carpathian Mountains[81] as far north as Poland and as far west as the regions of Moravia (part of the modern Czech Republic), some went as far east as Volhynia of western Ukraine, and the present-day Croatia where the Morlachs gradually disappeared, while the Catholic and Orthodox Vlachs took Croat and Serb national identity.[82]

The first written record about a Romance language spoken in the Middle Ages in the Balkans, near the Haemus Mons is from 587 AD. A Vlach muleteer accompanying the Byzantine army noticed that the load was falling from one of the animals and shouted to a companion Torna, torna, fratre! (meaning "Return, return, brother!"). Theophanes the Confessor recorded it as part of a 6th-century military expedition by Comentiolus and Priscus against the Avars. Historian Gheorghe I. Brătianu considers that these words "represent an expression from the Romanian language, as it was formed at that time in the Balkan and Danube regions"; "they probably belong to one and the most significant of the substrates on which our (Romanian) language was built".[83]

After the Avar Khaganate collapsed in the 790s, the First Bulgarian Empire became the dominant power of the region, occupying lands as far as the river Tisa.[84] The First Bulgarian Empire had a mixed population consisting of the Bulgar conquerors, Slavs and Vlachs (Romanians) but the Slavicisation of the Bulgar elite had already begun in the 9th century. Following the conquest of Southern and Central Transylvania around 830, people from the Bulgar Empire mined salt from mines in Turda, Ocna Mureș, Sărățeni and Ocnița. They traded and transported salt throughout the Bulgar Empire.[85]

A series of Arab historians from the 10th century are some of the first to mention Vlachs in Eastern/South Eastern Europe: Mutahhar al-Maqdisi (c.945-991) writes: "They say that in the Turkic neighborhood there are the Khazars, Russians, Slavs, Waladj (Vlachs), Alans, Greeks and many other peoples".[86] Ibn al-Nadīm (early 932–998) published in 998 the work Kitāb al-Fihrist mentioning "Turks, Bulgars and Vlahs" (using Blagha for Vlachs).[87][88]

The Byzantine chronicler Niketas Choniates writes that in 1164, Andronikos I Komnenos, the emperor Manuel I Komnenos's cousin, tried without success, to usurp the throne. Failing in his attempt, the Byzantine prince sought refuge in Halych but Andronikos I Komnenos was "captured by the Vlachs, to whom the rumor of his escape had reached, he was taken back to the emperor".[89][90][91]

The Byzantine chronicler John Kinnamos, presenting the campaign of Manuel I Komnenos against Hungary in 1166, reports that General Leon Vatatzes had under his command "a great multitude of Vlachs, who are said to be ancient colonies of those in Italy", an army that attacked the Hungarian possessions "about the lands near the Pontus called the Euxine", respectively the southeastern regions of Transylvania, "destroyed everything without sparing and trampled everything it encountered in its passage".[92][93][94][95]

By the 9th and 10th centuries, the nomadic Pechenegs conquered much of the steppes of Southeast Europe and the Crimean Peninsula.The Pecheneg wars against the Kievan Rus' caused some of the Slavs and Vlachs from North of the Danube to gradually migrate north of the Dniestr in the 10th and 11th centuries.[96]

The Second Bulgarian Empire founded by the Asen dynasty consisting of Bulgarians and Vlachs was founded in 1185 and lasted until 1396. Early rulers from the Asen dynasty (particularly Kaloyan) referred to themselves as "Emperors of Bulgarians and Vlachs". Later rulers, especially Ivan Asen II, styled themselves "Tsars (Emperors) of Bulgarians and Romans". An alternative name used in connection with the pre-mid Second Bulgarian Empire 13th century period is the Empire of Vlachs and Bulgarians;[97] variant names include the "Vlach–Bulgarian Empire", the "Bulgarian–Wallachian Empire".[98]

Royal charters wrote of the "Vlachs' land" in southern Transylvania in the early 13th century, indicating the existence of autonomous Romanian communities.[99] Papal correspondence mentions the activities of Orthodox prelates among the Romanians in Muntenia in the 1230s.[100] Béla IV of Hungary's land grant to the Knights Hospitallers in Oltenia and Muntenia shows that the local Vlach rulers were subject to the king's authority in 1247.[101][102]

The late 13th-century Hungarian chronicler Simon of Kéza states that the Vlachs were "shepherds and husbandmen" who "remained in Pannonia".[103][104] An unknown author's Description of Eastern Europe from 1308 likewise states that the Vlachs "were once the shepherds of the Romans" who "had over them ten powerful kings in the entire Messia and Pannonia".[105][106]

In the 14th century the Danubian Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia emerged to fight the Ottoman Empire. During the late Middle Ages, prominent medieval Romanian monarchs such as Bogdan of Moldavia, Stephen the Great, Mircea the Elder, Michael the Brave, or Vlad the Impaler took part actively in the history of Central Europe by waging tumultuous wars and leading noteworthy crusades against the then continuously expanding Ottoman Empire, at times allied with either the Kingdom of Poland or the Kingdom of Hungary in these causes.

Early Modern Age to Late Modern Age

[edit]

Eventually the entire Balkan peninsula was annexed by the Ottoman Empire. However, Moldavia and Wallachia (extending to Dobruja and Bulgaria) were not entirely subdued by the Ottomans as both principalities became autonomous (which was not the case of other Ottoman territorial possessions in Europe). Transylvania, a third region inhabited by an important majority of Romanian speakers, was a vassal state of the Ottomans until 1687, when the principality became part of the Habsburg possessions. The three principalities were united for several months in 1600 under the authority of Wallachian Prince Michael the Brave.[107]

Up until 1541, Transylvania was part of the Kingdom of Hungary, later (due to the conquest of Hungary by the Ottoman Empire) was a self-governed Principality governed by the Hungarian nobility. In 1699 it became a part of the Habsburg lands. By the end of the 18th century, the Austrian Empire was awarded by the Ottomans with the region of Bukovina and, in 1812, the Russians occupied the eastern half of Moldavia, known as Bessarabia through the Treaty of Bucharest of 1812.[108]

In the context of the 1848 Romanticist and liberal revolutions across Europe, the events that took place in the Grand Principality of Transylvania were the first of their kind to unfold in the Romanian-speaking territories. On the one hand, the Transylvanian Saxons and the Transylvanian Romanians (with consistent support on behalf of the Austrian Empire) successfully managed to oppose the goals of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, with the two noteworthy historical figures leading the common Romanian-Saxon side at the time being Avram Iancu and Stephan Ludwig Roth.

On the other hand, the Wallachian revolutions of 1821 and 1848 as well as the Moldavian Revolution of 1848, which aimed for independence from Ottoman and Russian foreign rulership, represented important impacts in the process of spreading the liberal ideology in the eastern and southern Romanian lands, in spite of the fact that all three eventually failed. Nonetheless, in 1859, Moldavia and Wallachia elected the same ruler, namely Alexander John Cuza (who reigned as Domnitor) and were thus unified de facto, resulting in the United Romanian Principalities for the period between 1859 and 1881.

During the 1870s, the United Romanian Principalities (then led by Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen Domnitor Carol I) fought a War of Independence against the Ottomans, with Romania's independence being formally recognised in 1878 at the Treaty of Berlin.

Although the relatively newly founded Kingdom of Romania initially allied with Austria-Hungary, Romania refused to enter World War I on the side of the Central Powers, because it was obliged to wage war only if Austria-Hungary was attacked. In 1916, Romania joined the war on the side of the Triple Entente.

As a result, at the end of the war, Transylvania, Bessarabia, and Bukovina were awarded to Romania, through a series of international peace treaties, resulting in an enlarged and far more powerful kingdom under King Ferdinand I. As of 1920, the Romanian people was believed to number over 15 million solely in the region of the Romanian kingdom, a figure larger than the populations of Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands combined.[109]

During the interwar period, two additional monarchs came to the Romanian throne, namely Carol II and Michael I. This short-lived period was marked, at times, by political instabilities and efforts of maintaining a constitutional monarchy in favour of other, totalitarian regimes such as an absolute monarchy or a military dictatorship.

Contemporary Era

[edit]During World War II, the Kingdom of Romania lost territory both to the east and west, as Northern Transylvania became part of the Kingdom of Hungary through the Second Vienna Award, while Bessarabia and northern Bukovina were taken by the Soviets and included in the Moldavian SSR, respectively Ukrainian SSR. The eastern territory losses were facilitated by the Molotov–Ribbentrop Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact.

After the end of the war, the Romanian Kingdom managed to regain territories lost westward but was nonetheless not given Bessarabia and northern Bukovina back, the aforementioned regions being forcefully incorporated into the Soviet Union (USSR). Subsequently, the Soviet Union imposed a communist government and King Michael was forced to abdicate and leave for exile, subsequently settling in Switzerland, while Petru Groza remained the head of the government of the Socialist Republic of Romania (RSR). Nicolae Ceaușescu became the head of the Romanian Communist Party (PCR) in 1965 and his severe rule of the 1980s was ended by the Romanian Revolution of 1989.

The chaos of the 1989 revolution brought to power the dissident communist Ion Iliescu as president (largely supported by the FSN). Iliescu remained in power as head of state until 1996, when he was defeated by CDR-supported Emil Constantinescu in the 1996 general elections, the first in post-communist Romania that saw a peaceful transition of power. Following Constantinescu's single term as president from 1996 to 2000, Iliescu was re-elected in late 2000 for another term of four years. In 2004, Traian Băsescu, the PNL-PD candidate of the Justice and Truth Alliance (DA), was elected president. Five years later, Băsescu (solely supported by the PDL this time) was narrowly re-elected for a second term in the 2009 presidential elections.

In 2014, the PNL-PDL candidate (as part of the larger Christian Liberal Alliance or ACL for short; also endorsed by the Democratic Forum of Germans in Romania, FDGR/DFDR for short respectively) Klaus Iohannis won a surprise victory over former Prime Minister and PSD-supported contender Victor Ponta in the second round of the 2014 presidential elections. Thus, Iohannis became the first Romanian president stemming from an ethnic minority of the country (as he belongs to the Romanian-German community, being a Transylvanian Saxon). In 2019, the PNL-supported Iohannis was re-elected for a second term as president after a second round landslide victory in the 2019 Romanian presidential election (being also supported in that round by PMP and USR as well as by the FDGR/DFDR in both rounds).

In the meantime, Romania's major foreign policy achievements were the alignment with Western Europe and the United States by joining the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) back in 2004 and the European Union three years later, in 2007. Current national objectives of Romania include adhering to the Schengen Area, the Eurozone as well as the OECD (i.e. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development).

Language

[edit]

During the Middle Ages, Romanian was isolated from the other Romance languages, and borrowed words from the nearby Slavic languages (see Slavic influence on Romanian). Later on, it borrowed a number of words from German, Hungarian, and Turkish.[110] During the modern era, most neologisms were borrowed from French and Italian, though the language has increasingly begun to adopt English borrowings.

The origins of the Romanian language, a Romance language, can be traced back to the Roman colonisation of the region. The basic vocabulary is of Latin origin,[109] although there are some substratum words that are assumed to be of Dacian origin. It is the most spoken Eastern Romance language and is closely related to Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian, and Istro-Romanian, all three part of the same sub-branch of Romance languages.

Since 2013, the Romanian Language Day is officially celebrated on 31 August in Romania.[111] In Moldova, it is officially celebrated on the same day since 2023.[112]

As of 2017, an Ethnologue estimation puts the (worldwide) number of Romanian speakers at approximately 24.15 million.[113] The 24.15 million, however, represent only speakers of Romanian, not all of whom are necessarily ethnic Romanians. Also, this number does not include ethnic-Romanians who no longer speak the Romanian language.

Names for Romanians

[edit]In English, Romanians are usually called Romanians and very rarely Rumanians or Roumanians, except in some historical texts, where they are called Roumans or Vlachs.[citation needed]

Etymology of the name Romanian (român)

[edit]

The name Romanian is derived from Latin romanus, meaning "Roman".[114] Under regular phonetical changes that are typical to the Romanian language, the name romanus over the centuries transformed into rumân [ruˈmɨn]. An older form of român was still in use in some regions. Socio-linguistic evolutions in the late 18th century led to a gradual preponderance of the român spelling form, which was then generalised during the National awakening of Romania of early 19th century.[115] Several historical sources show the use of the term "Romanian" among the medieval or early modern Romanian population. One of the earliest examples comes from the Nibelungenlied, a German epic poem from before 1200 in which a "Duke Ramunc from the land of Vlachs (Wallachia)" is mentioned. "Vlach" was an exonym used almost exclusively for the Romanians during the Middle Ages. It has been argued by some Romanian researchers that "Ramunc" was not the name of the duke, but a name that highlighted his ethnicity. Other old documents, especially Byzantine or Hungarian ones, make a correlation between the old Romanians as Romans or their descendants.[116] Several other documents, notably from Italian travelers into Wallachia, Moldavia and Transylvania, speak of the self-identification, language and culture of the Romanians, showing that they designated themselves as "Romans" or related to them in up to 30 works.[117] One example is Tranquillo Andronico's 1534 writing that states that the Vlachs "now call themselves Romans".[118] Another one is Francesco della Valle's 1532 manuscripts that state that the Romanians from Wallachia, Moldavia and Transylvania preserved the name "Roman" and cites the sentence "Sti Rominest?" (știi românește?, "do you speak Romanian?").[119] Authors that travelled to modern Romania who wrote about it in 1574,[120] 1575[121] and 1666 also noted the use of the term "Romanian".[122] From the Middle Ages, Romanians bore two names, the exonym (one given to them by foreigners) Wallachians or Vlachs, under its various forms (vlah, valah, valach, voloh, blac, olăh, vlas, ilac, ulah, etc.), and the endonym (the name they used for themselves) Romanians (Rumâni/Români).[123] The first mentions by Romanians of the endonym are contemporary with the earliest writings in Romanian from the sixteenth century.[124]

According to Tomasz Kamusella, at the time of the rise of Romanian nationalism during the early 19th century, the political leaders of Wallachia and Moldavia were aware that the name România was identical to Romania, a name that had been used for the former Byzantine Empire by its inhabitants. Kamusella continues by stating that they preferred this ethnonym in order to stress their presumed link with Ancient Rome and that it became more popular as a nationalistic form of referring to all Romanian-language speakers as a distinct and separate nation during the 1820s.[125] Raymond Detrez asserts that român, derived from the Latin Romanus, acquired at a certain point the same meaning of the Greek Romaios; that of Orthodox Christian.[126] Wolfgang Dahmen claims that the meaning of romanus (Roman) as "Christian", as opposed to "pagan", which used to mean "non-Roman", may have contributed to the preservation of this word as an ethonym of the Romanian people, under the meaning of "Christian".[127]

Daco-Romanian

[edit]To distinguish Romanians from the other Romanic peoples of the Balkans (Aromanians, Megleno-Romanians, and Istro-Romanians), the term Daco-Romanian is sometimes used to refer to those who speak the standard Romanian language and live in the former territory of ancient Dacia (today comprising mostly Romania and Moldova) and its surroundings (such as Dobruja or the Timok Valley, the latter region part of the former Roman province of Dacia Ripensis).[128][129]

Etymology of the term Vlach

[edit]The name of "Vlachs" is an exonym that was used by Slavs to refer to all Romanized natives of the Balkans. It holds its origin from ancient Germanic—being a cognate to "Welsh" and "Walloon"—and perhaps even further back in time, from the Roman name Volcae, which was originally a Celtic tribe. From the Slavs, it was passed on to other peoples, such as the Hungarians (Oláh) and Greeks (Vlachoi) (see the Etymology section of Vlachs). Wallachia, the Southern region of Romania, takes its name from the same source.

Nowadays, the term Vlach is more often used to refer to the Romanized populations of the Balkans who speak Daco-Romanian, Aromanian, Istro-Romanian, and Megleno-Romanian.

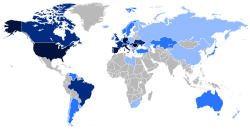

Romanians outside Romania

[edit]

Most Romanians live in Romania, where they constitute a majority; Romanians also constitute a minority in the countries that neighbour Romania. Romanians can also be found in many countries, notably in the other EU countries, particularly in Italy, Spain, Germany, the United Kingdom and France; in North America in the United States and Canada; in Israel; as well as in Brazil, Australia, Argentina, and New Zealand among many other countries. Italy and Spain have been popular emigration destinations, due to a relatively low language barrier, and both are each now home to about a million Romanians. With respect to geopolitical identity, many individuals of Romanian ethnicity in Moldova prefer to identify themselves as Moldovans.[67][68]

The contemporary total population of ethnic Romanians cannot be stated with any degree of certainty. A disparity can be observed between official sources (such as census counts) where they exist, and estimates which come from non-official sources and interested groups. Several inhibiting factors (not unique to this particular case) contribute towards this uncertainty, which may include:

- A degree of overlap may exist or be shared between Romanian and other ethnic identities in certain situations, and census or survey respondents may elect to identify with one particular ancestry but not another, or instead identify with multiple ancestries;[130]

- Counts and estimates may inconsistently distinguish between Romanian nationality and Romanian ethnicity (i.e. not all Romanian nationals identify with Romanian ethnicity, and vice versa);[130]

- The measurements and methodologies employed by governments to enumerate and describe the ethnicity and ancestry of their citizens vary from country to country. Thus the census definition of "Romanian" might variously mean Romanian-born, of Romanian parentage, or also include other ethnic identities as Romanian which otherwise are identified separately in other contexts.[130]

For example, the decennial US Census of 2000 calculated (based on a statistical sampling of household data) that there were 367,310 respondents indicating Romanian ancestry (roughly 0.1% of the total population).[131]

The actual total recorded number of foreign-born Romanians was only 136,000.[132] However, some non-specialist organisations have produced estimates which are considerably higher: a 2002 study by the Romanian-American Network Inc. mentions an estimated figure of 1,200,000[46] for the number of Romanian Americans. Which makes the United States home to the largest Romanian community outside Romania.

This estimate notes however that "...other immigrants of Romanian national minority groups have been included such as: Armenians, Germans, Gypsies, Hungarians, Jews, and Ukrainians". It also includes an unspecified allowance for second- and third-generation Romanians, and an indeterminate number living in Canada. An error range for the estimate is not provided. For the United States 2000 Census figures, almost 20% of the total population did not classify or report an ancestry, and the census is also subject to undercounting, an incomplete (67%) response rate, and sampling error in general.

In Republika Srpska, one of the two entities constituting Bosnia and Herzegovina together with the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Romanians are legally recognized as an ethnic minority.[133]

Culture

[edit]Contributions to contemporary culture

[edit]Romanians have played and contributed a major role in the advancement of the arts, culture, sciences, technology and engineering.[citation needed]

In the history of aviation, Traian Vuia and Aurel Vlaicu built and tested some of the earliest aircraft designs, while Henri Coandă discovered the Coandă effect of fluidics. Victor Babeș discovered more than 50 germs and a cure for a disease named after him, babesiosis; biologist Nicolae Paulescu was among the first scientists to identify insulin. Another biologist, Emil Palade, received the Nobel Prize for his contributions to cell biology. George Constantinescu created the theory of sonics, while mathematician Ștefan Odobleja has been claimed as "the ideological father behind cybernetics" – his work The Consonantist Psychology (Paris, 1938) was supposedly the main source of inspiration for N. Wiener's Cybernetics (Paris, 1948). Lazăr Edeleanu was the first chemist to synthesize amphetamine and also invented the modern method of refining crude oil.[citation needed]

In the arts and culture, prominent figures were George Enescu (music composer, violinist, professor of Sir Yehudi Menuhin), Constantin Brâncuși (sculptor), Eugène Ionesco (playwright), Mircea Eliade (historian of religion and novelist), Emil Cioran (essayist, Prix de l'Institut Français for stylism) and Angela Gheorghiu (soprano). More recently, filmmakers such as Cristi Puiu and Cristian Mungiu have attracted international acclaim, as has fashion designer Ioana Ciolacu.[citation needed]

In sports, Romanians have excelled in a variety of fields, such as football (Gheorghe Hagi), gymnastics (Nadia Comăneci, Lavinia Miloșovici etc.), tennis (Ilie Năstase, Ion Țiriac, Simona Halep), rowing (Ivan Patzaichin) and handball (four times men's World Cup winners). Count Dracula is a worldwide icon of Romania. This character was created by the Irish fiction writer Bram Stoker, based on some stories spread in the late Middle Ages by the frustrated German tradesmen of Kronstadt (Brașov) and on some vampire folk tales about the historic Romanian figure of Prince Vlad Țepeș.[citation needed]

Religion

[edit]Almost 90% of all Romanians consider themselves religious.[134] The vast majority are Eastern Orthodox Christians, belonging to the Romanian Orthodox Church (a branch of Eastern Orthodoxy, or Eastern Orthodox Church, together with the Greek Orthodox, Orthodox Church of Georgia and Russian Orthodox Churches, among others). Romanians form the third largest ethno-linguistic group among Eastern Orthodox in the world.[135][136]

According to the 2022 census, 91.5% of ethnic Romanians in Romania identified themselves as Romanian Orthodox (in comparison to 73.6% of Romania's total population, including other ethnic groups), followed by 3.6% as Protestants and 2.5% as Catholics.[137] However, the actual rate of church attendance is significantly lower and many Romanians are only nominally believers. For example, according to a 2006 Eurobarometer poll, only 23% of Romanians attend church once a week or more.[138] A 2006 poll conducted by the Open Society Foundations found that only 33% of Romanians attended church once a month or more.[139]

-

Romano-Gothic Densuș Church, Hunedoara, Transylvania

-

Romano-Gothic Strei Church, Hunedoara, Transylvania

-

St. Nicholas Church, Brașov, Transylvania

-

Nativity of St. John the Baptist Church, Piatra Neamț, Moldavia

-

Metropolitan Cathedral, Iași, Moldavia

-

Putna Monastery, Bukovina

Romanian Catholics are present in Transylvania, Banat, Bukovina, Bucharest, and parts of Moldavia, belonging to both the Roman Catholic Church (297,246 members) and the Romanian Greek Catholic Church (124,563 members). According to the 2011 Romanian census, 2.5% of ethnic Romanians in Romania identified themselves as Catholic (in comparison to 5% of Romania's total population, including other ethnic groups). Around 1.6% of ethnic Romanians in Romania identify themselves as Pentecostal, with the population numbering 276,678 members. Smaller percentages are Protestant, Jews, Muslims, agnostic, atheist, or practice a traditional religion.

-

Roman Catholic Saint Joseph Cathedral, Bucharest, Wallachia

-

Roman Catholic St. Michael's Cathedral, Alba Iulia, Transylvania

-

Greek Catholic Cathedral of the Holy Trinity, Blaj, Transylvania

-

Greek Catholic Assumption of Mary Cathedral, Baia Mare, Transylvania

-

Roman Catholic St. John of Nepomuk Church, Suceava, Bukovina

-

Roman Catholic St. George Cathedral in Timișoara, Banat

There are no official dates for the adoption of religions by the Romanians. Based on linguistic and archaeological findings, historians suggest that the Romanians' ancestors acquired polytheistic religions in the Roman era, later adopting Christianity, most likely by the 4th century AD when decreed by Emperor Constantine the Great as the official religion of the Roman Empire.[140] Like in all other Romance languages, the basic Romanian words related to Christianity are inherited from Latin, such as God (Dumnezeu < Domine Deus), church (biserică < basilica), cross (cruce < crux, -cis), angel (înger < angelus), saint (regional: sfân(t) < sanctus), Christmas (Crăciun < creatio, -onis), Christian (creștin < christianus), Easter (paște < paschae), sin (păcat < peccatum), to baptise (a boteza < batizare), priest (preot < presbiterum), to pray (a ruga < rogare), faith (credință < credentia), and so on.

After the Roman Catholic-Eastern Orthodox Schism of 1054, there existed a Roman Catholic Diocese of Cumania for a short period of time, from 1228 to 1241. However, this seems to be the exception, rather than the rule, as in both Wallachia and Moldavia the state religion was Eastern Orthodox. Until the 17th century, the official language of the liturgy was Old Church Slavonic (a.k.a. Middle Bulgarian). Then, it gradually changed to Romanian.

Symbols

[edit]In addition to the colours of the Romanian flag, each historical province of Romania has its own characteristic symbol:

- Banat: Trajan's Bridge

- Dobruja: Dolphin

- Moldavia (including Bukovina and Bessarabia): Aurochs/Wisent

- Oltenia: Lion

- Transylvania (including Crișana and Maramureș): Black eagle or Turul

- Wallachia: Eagle

The coat of arms of Romania combines these together.

Customs

[edit]Traditional costumes

[edit]-

Romanians from Cluj-Napoca, Cluj County, Transylvania, Romania, in traditional folk costumes, dancing on the occasion of the Mărțișor holiday (2006).

-

Painting of Transylvanian Romanian peasants from Abrud by Ion Theodorescu-Sion

-

Traditional Romanian peasant costumes to the left, followed from left to right by Hungarian, Slavic, and German ones

-

Romanian peasant costume from Bukovina, early 20th century

-

Romanians from Bukovina, early 20th century postcard

-

Painting of a young Wallachian shepherd in the early 20th century by Ipolit Strâmbu

-

Romanian immigrants in New York City, late 19th century

Relationship to other ethnic groups

[edit]The closest ethnic groups to the Romanians are the other Romanic peoples of Southeastern Europe: the Aromanians (Macedo-Romanians), the Megleno-Romanians, and the Istro-Romanians. The Istro-Romanians are the closest ethnic group to the Romanians, and it is believed they left Maramureș, Transylvania about a thousand years ago and settled in Istria, Croatia.[141] Numbering about 500 people still living in the original villages of Istria while the majority left for other countries after World War II (mainly to Italy, United States, Canada, Spain, Germany, France, Sweden, Switzerland, Romania, and Australia), they speak the Istro-Romanian language, the closest living relative of Romanian. On the other hand, the Aromanians and the Megleno-Romanians are Romance peoples who live south of the Danube, mainly in Greece, Albania, North Macedonia and Bulgaria although some of them migrated to Romania in the 20th century. It is believed that they diverged from the Romanians in the 7th to 9th century, and currently speak the Aromanian language and Megleno-Romanian language, both of which are Eastern Romance languages, like Romanian, and are sometimes considered by traditional Romanian linguists to be dialects of Romanian.

Genetics

[edit]

A Bulgarian study from 2013 shows genetic similarity between Thracians (8-6 century BC), medieval Bulgarians (8–10 century AD), and modern Bulgarians, highlighting highest resemblance between them and Romanians, Northern Italians and Northern Greeks.[143] A genetic study published in Scientific Reports in 2019 examined the mtDNA of 25 Thracian remains in Bulgaria from the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC. They were found to harbor a mixture of ancestry from Western Steppe Herders (WSHs) and Early European Farmers (EEFs), supporting the idea that Southeast Europe was the link between Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean.[144]

The prevailing Y-chromosome in Wallachia (Ploiești, Dolj), Moldavia (Piatra Neamț, Buhuși), Dobruja (Constanța), and northern Republic of Moldova is recorded to be Haplogroup I.[145][146] Subclades I1 and I2 can be found in most present-day European populations, with peaks in some Northern European and Southeastern European countries. Haplogroup I occurs at 32% in Romanians.[147] The frequency of I2a1 (I-P37) in the Balkans according to older researches was considered to be the result of "pre-Slavic" paleolithic settlement. Peričić et al. (2005) for instance placed its expansion to have occurred "not earlier than the YD to Holocene transition and not later than the early Neolithic".[148][149] However, the prehistoric autochthonous origin of the haplogroup I2 in the Balkans is now considered as outdated, as already Battaglia et al. (2009) observed highest variance of the haplogroup in Ukraine, and Zupan et al. (2013) noted that it suggests it arrived with Slavic migration from the homeland which was in present-day Ukraine.[150] Although it is dominant among the modern Slavic peoples on the territory of the former Balkan provinces of the Roman Empire, until now it was not found among the samples from the Roman period and is almost absent in contemporary population of Italy.[151] According to Pamjav et al. (2019) and Fóthi et al. (2020), the distribution of such ancestral subclades among contemporary carriers indicates a rapid expansion from Southeastern Poland, and is mainly related to the Slavs and their medieval migration, which led to the largest demographic explosion that occurred in the Balkans.[151][152] According to a 2023 archaeogenetic study, I2a-L621 is absent in the antiquity and appears only since the Early Middle Ages "always associated with Eastern European related ancestry in the autosomal genome, which supports that these lineages were introduced in the Balkans by Eastern European migrants during the Early Medieval period."[153]

A similar result was cited in a study investigating the genetic pool of people from Republic of Moldova, concluded about the representative samples taken for comparison from Romanians from the towns of Piatra-Neamț and Buhuși that "the most common Y haplogroup in this population was I-M423 (40.7%). This is the highest frequency of the I-M423 haplogroup reported so far outside of the northwest Balkans. The next most frequent among Romanian males was haplogroup R-M17* (16.7%), followed by R-M405 (7.4%), E-v13 and R-M412* (both 5.6%)."[154] The I-M423 haplogroup is a subclade of I2a, a haplogroup prosperous in the Starcevo culture and its possible offshoot Cucuteni–Trypillia culture (4800-3000 BCE). The high concentration of I2a1b-L621, the main subclade, is attributed to Bronze Age and Early Iron Age migrations (Dacians, Thracians, Illyrians) and the medieval Slavic migrations.[155]

According to a Y-chromosome analysis of 335 sampled Romanians, 15% of them belong to R1a.[157] Haplogroup R1a, is a human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup which is distributed in a large region in Eurasia, extending from Scandinavia and Central Europe to southern Siberia and South Asia.[158][159] Haplogroup R1a among Romanians is entirely from the Eastern European variety Z282 and may be a result of Baltic, Thracian or Slavic descent. 12% of the Romanians belong to Haplogroup R1b, the Alpino-Italic branch of R1b is at 2% a lower frequency recorded than other Balkan peoples.[160] The eastern branches of R1b represent 7%, they prevail in parts of Eastern and Central Europe as a result of Ancient Greek colonisation – in parts of Sicily as well.[160][161] Other studies analyzing the haplogroup frequency among Romanians came to similar results.[146]

Delving into the regional differences of Mitochondrial DNA of Romanians, a 2014 study emphasised the different position of North and South Romanian populations (i.e. inside and outside of the Carpathian range) in terms of mitochondrial haplotype variability. The population within the Carpathian range was found to have haplogroup H at 59.7% frequency, U at 11.3%, K and HV at 3.23% each, and M, X and A at 1.61% each. The South Romanian population also showed the highest frequency in haplogroup H at 47% (lower than in the sample from the North of Romania), haplogroup U showed a noticeable frequency at 17% (higher than in the sample from North Romania), haplogroups HV and K at 10.61% and 7.58%, respectively, while haplogroups M, X and A were absent. Comparing the results to European and international samples, the study proposes a weak differentiated distribution of mitochondrial haplogroups between inner and outer Carpathian population (rather than north–south boundary) based on higher frequency for the haplogroup J and haplogroup K2a in the Southern Romanian sample - considered as markers of the Neolithic expansion in Europe from the Near East, the absence of K2a and the presence of haplogroup M in Northern Romanian sample - with higher frequency in Western and Southern Asia, and the inclusion of both Romanian populations within the range of the European mitochondrial variability, rather than being closer to the Near Eastern populations. The North Romanian sample was also found to be slightly separated from the other samples included in the study.[162]

A 2017 paper concentrated on the Mitochondrial DNA of Romanians, showed how Romania has been "a major crossroads between Asia and Europe" and thus "experienced continuous migration and invasion episodes"; while stating that previous studies show Romanians "exhibit genetic similarity with other Europeans". The paper also mentions how "signals of Asian maternal lineages were observed in all Romanian historical provinces, indicating gene flow along the migration routes through East Asia and Europe, during different time periods, namely, the Upper Paleolithic period and/or, with a likely greater preponderance, the Middle Ages", at low frequency (2.24%). The study analysed 714 samples, representative to the 41 counties of Romania, and grouped them in 4 categories corresponding to historical Romanian provinces: Wallachia, Moldavia, Transylvania, and Dobruja. The majority was classified within 9 Eurasian mitochondrial haplogroups (H, U, K, T, J, HV, V, W, and X), while also finding sequences that belonged to the most frequent Asian haplogroups (haplogroups A, C, D, I - at 2.24% overall frequency, and M and N) and African haplogroup L (two samples in Wallachia and one in Dobruja). The H, V, and X haplogroups were detected at higher frequencies in Transylvania, while the frequency of U and N was lower, with M being absent, interpreted as an indicator of genetic proximity of Transylvania to Central European populations, in contrast to the other three provinces, which showed resemblance to Balkan populations. The Dobrujan samples showed a larger contribution of genes from Southwestern Asia which the authors attributed to a larger Asian influence historically and/or its smaller sample size compared to that of the other populations included.[163]

A 2023 archaeogenetic study published in Cell, argued that the spread of Slavic language in Southeastern Europe was because of large movements of people with specific Eastern European ancestry, and that more than half of the ancestry of most peoples in the Balkans today originates from the medieval Slavic migrations, with around 67% in Croats, 58% in Serbs, 55% in Romanians, 51% in Bulgarians, 40% in Greek Macedonians, 31% in Albanians, 30% in Peloponnesian Greeks, and 4–20% in Greeks from the Aegean Islands.[164][165]

A 2025 archaeogenetic study calculates Medieval Slavic ancestry among Romanians in different regions between 45-48%.[166][167]

Ethnogenesis

[edit]Three theories account for the ethnogenesis of the Romanian people. One, known as the Daco-Roman continuity theory, posits that they are descendants of Romans and Romanized indigenous peoples (Dacians) living in the Roman Province of Dacia, while the other posits that the Romanians are descendants of Romans and Romanized indigenous populations of the former Roman provinces of Illyricum, Moesia, Thracia, and Macedonia, and the ancestors of Romanians later migrated from these Roman provinces south of the Danube into the area which they inhabit today. The third theory also known as the admigration theory, proposed by Dimitrie Onciul (1856–1923), posits that the formation of the Romanian people occurred in the former "Dacia Traiana" province, and in the central regions of the Balkan Peninsula.[168][169][170] However, the Balkan Vlachs' northward migration ensured that these centers remained in close contact for centuries.[168][171] This theory is a compromise between the immigrationist and the continuity theories.[168]

Demographics

[edit]The largest ethnic group in Romania is ethnic Romanians, followed by Hungarians and Romani people.[172]

Maps

[edit]-

Mid-19th century French map depicting Romanians in Central and Eastern Europe

-

Modern distribution of the Eastern Romance-speaking ethnic groups (including, most notably, the Romanians)

-

Romanians in Central Europe (coloured in blue), 1880

-

Ethnic map of Austria-Hungary and Romania, 1892

-

British map depicting territories inhabited by Eastern Romance peoples before the outbreak of World War I

-

Romanian speakers in Central and Eastern Europe, early 20th century

-

Map of the Kingdom of Romania at its greatest extent (1920–1940)

-

Geographic distribution of ethnic Romanians in the early 21st century

-

Notable regions with inhabited by Eastern Romance speakers at the beginning of the 21st century

-

Map highlighting the three main sub-groups of Daco-Romanians

-

Geographic distribution of Romanians in Romania (coloured in purple) at commune level (2011 census)

-

Geographic distribution of Romanian in Romania (coloured in purple) at county level (2011 census)

See also

[edit]- List of notable Romanians

- List of Romanian inventors and discoverers

- Romance languages

- Slavic influence on Romanian

- Legacy of the Roman Empire

- Romanian diaspora

- Romanians in Germany

- Romanian British

- Romanian French

- Romanians of Italy

- Romanians of Spain

- Romanian Australians

- Romanian Americans

- Romanian Canadians

- Romanians of Serbia

- Romanian language in Serbia

- Romanians of Ukraine

- Romanians of Hungary

- Romanians of Bulgaria

- History of Romania

- Thraco-Roman

- Daco-Roman

- Brodnici

- Morlachs

- Gorals

- Moravian Wallachia

- Culture of Romania

- Art of Romania

- Geography of Romania

- Folklore of Romania

- Music of Romania

- Sport in Romania

- Name of Romania

- Romanian cuisine

- Romanian literature

- Minorities in Romania

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ "6–8 Million Romanians live outside Romania's borders". Ziua Veche. 13 December 2013. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "Population and housing census, 2021 - provisional results". Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ Statistică, Biroul Naţional de (2 August 2013). "// Recensămîntul populației și al locuințelor 2014". statistica.gov.md. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ Includes additional 177,635 Moldovans in Transnistria; as per the 2004 census in Transnistria

- ^ "Romeni in Italia - statistiche e distribuzione per regione" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ "Ausländische Bevölkerung nach Altersgruppen und ausgewählten Staatsangehörigkeiten". Statistisches Bundesamt (in German). Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ "Statistischer Bericht - Mikrozensus - Bevölkerung nach Migrationshintergrund - Erstergebnisse 2022". 20 April 2023. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ "Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund".

- ^ "Población por comunidades y provincias, país de nacimiento, edad (Grupos quinquenales) y sexo" (PDF). Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ "Estadística de residentes extranjeros en España" (PDF). Ministry of Inclusion, Social Security and Migration (in Spanish). p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ "Población extranjera por Nacionalidad, comunidades, Sexo y Año. Datos provisionales 2020". INE. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ "Population of the United Kingdom by country of birth and nationality, July 2020 to June 2021". ons.gov.uk. Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 3 January 2024. Retrieved 5 February 2023..

- ^ "Dataset: Population of the United Kingdom by Country of Birth and Nationality". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ "According to the Secretary of State Romanian, Florin Cârciu: In France alone we have 500,000 Romanians, more than what the French State declares today". Adevarul. 19 May 2022. Archived from the original on 31 January 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023..

- ^ "Câţi români muncesc în străinătate şi unde sunt cei mai mulţi". EWconomica.net. 30 November 2013. Archived from the original on 28 October 2016. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ^ "Anzahl der Ausländer in Österreich nach den zehn wichtigsten Staatsangehörigkeiten zu Jahresbeginn 2024". Statista. Archived from the original on 30 November 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ As per the 2001 Ukrainian National Census (data-ro

- ^ "Belgium: foreign population, by origin 2019". Statista.

- ^ V. M. (18 March 2016). "Migratie in cijfers en in rechten 2018" (PDF). HotNews.ro (in Dutch). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ "Announcement of the demographic and social characteristics of the Resident Population of Greece according to the 2011 Population – Housing Census" (PDF) (Press release). 23 August 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 December 2013.

- ^ "National statistics of Denmark". statistikbanken.dk. 11 August 2025. Retrieved 22 August 2025.

- ^ "Bevolking; generatie, geslacht, leeftijd en herkomstgroepering, 1 januari". Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ "Câţi români au părăsit România pentru a trăi în străinătate". 25 September 2015. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ Vukovich, Gabriella (2018). Mikrocenzus 2016 – 12. Nemzetiségi adatok [2016 microcensus – 12. Ethnic data] (PDF) (in Hungarian). Budapest: Hungarian Central Statistical Office. ISBN 978-963-235-542-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ "Utrikes födda samt födda i Sverige med en eller två utrikes födda föräldrar efter födelseland/ursprungsland, 31 December 2017, totalt". Statistics Sweden / Befolkning efter födelseland, ålder, kön och år. Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "Census 2016 Summary Results – Part 1" (PDF). Central Statistics Office. 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ "Cyprus 2011 census". Cystat.gov.cy. Archived from the original on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ^ "Становништво према националној припадности" (in Serbian). Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 June 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ^ "Permanent and non permanent resident population by canton, sex, citizenship, country of birth and age, 2014–2015". Federal Statistical Office. 26 August 2016. Archived from the original on 21 November 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ "Immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant parents, 1 January 2022". Statistics Norway (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- ^ Mădălin Danciu (31 December 2018). "Foreigners in the Czechia by citizenship". CZSO. Archived from the original on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ "Foreigners by category of residence, sex, and citizenship as at 31 December 2016". Czso.cz. Archived from the original on 12 January 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ Ana Ilie (20 July 2015). "Pentru ce facem moschee la București: În căutarea românilor ortodocși din Turcia". Ziare.com (in Romanian). Archived from the original on 18 March 2022. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ "Population by nationalities in detail 2011 - 2019". Statistiques // Luxembourg. Archived from the original on 10 September 2016.

- ^ Ambasada României în Polonia. "Comunitatea românească din Polonia". Ambasada României în Republica Polonă (in Romanian). Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ Andrei Luca Popescu (21 December 2015). "HARTA românilor plecați în străinătate. Topul țărilor UE în care românii reprezintă cea mai mare comunitate". Gândul (in Romanian). Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Statistics Finland (20 February 2019). "Statistics Finland's PX-Web databases".[permanent dead link]

- ^ "2010 Russia Census". Russian Federation Statistics Office. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ Ambasada României în Regatul Danemarcei (9 March 2019). "Comunitatea româneacă din Islanda". Ambasada României în Regatul Danemarcei (in Romanian). Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ "2011 Bulgarian Census". Censusresults.nsi.bg. Archived from the original on 19 December 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Romania). "Bosnia și Herțegovina − Comunitatea românească" (in Romanian). Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ "Total ancestry categories tallied for people with one or more ancestry categories reported, 2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. 2014. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau, 2009 American Community Survey". Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ^ "Romanian-American Community". Romanian-American Network Inc. Archived from the original on 13 January 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2008.

- ^ "2000 Census". Census.gov. Archived from the original on 23 July 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ a b Romanian Communities Allocation in United States: Study of Romanian-American population (2002), Romanian-American Network, Inc. Retrieved 14 October 2005. Their figure of 1.2 million includes "200,000–225,000 Romanian Jews", 50,000–60,000 Germans from Romania, etc.

- ^ "2011 National Household Survey: Data tables". 12.statcan.gc.ca. 8 May 2013. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ Statistics Canada (8 May 2013). "2011 National Household Survey: Data tables". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ "Population and Housing Census 2020". INEGI. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ "Comunitatea română" [Romanian Community]. brasilia.mae.ro. 29 July 2025. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ^ "AMERICA LATINĂ « DRP – Departamentul pentru Romanii de Pretutindeni". Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012. Departamentul pentru Românii de Pretutindeni America Latina

- ^ "The Week of the Romanian Diaspora in Argentina – The immigration of the Romanians to Argentina". Imperialtransilvania. 6 December 2016. Archived from the original on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "Câți români au părăsit România pentru a trăi în străinătate" (in Romanian). 25 September 2015. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ The People of Australia (PDF). Australian Government, Department of Immigration and Border Protection. 2014. ISBN 978-1-920996-23-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- ^ "Australia and New Zealand". Romanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 1 August 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ^ a b "Romania - International emigrant stock 2019". Archived from the original on 26 September 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ V. C. (11 March 2011). "Câți români sunt în Japonia? Invazia dansatoarelor românce". HotNews.ro (in Romanian). Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ Anca Melinte (25 September 2015). "Câți români au părăsit România pentru a trăi în străinătate". Viața liberă (in Romanian).

- ^ "Romanian ambassador says his country, Jordan maintain excellent partnership". Jordan news agency. 30 November 2022.

- ^ "Românul de milioane din Qatar". Digi24 (in Romanian). 16 May 2015.

- ^ "Ethnic composition, religion and language skills in the Republic of Kazakhstan". www.stat.kz. 2011. Archived from the original (RAR) on 11 May 2011.

- ^ "Socio-economic development of the Republic of Kazakhstan". stat.gov.kz. Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ Pop, Ioan-Aurel (1996). Romanians and Hungarians from the 9th to the 14th century. Romanian Cultural Foundation. ISBN 0-88033-440-1. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

We could say that contemporary Europe is made up of three large groups of peoples, divided on the criteria of their origin and linguistic affiliation. They are the following: the Romanic or neo-Latin peoples (Italians, Spaniards, Portuguese, French, Romanians, etc.), the Germanic peoples (Germans proper, English, Dutch, Danes, Norwegians, Swedes, Icelanders, etc.), and the Slavic peoples (Russians, Ukrainians, Belorussians, Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, Bulgarians, Serbs, Croats, Slovenians, etc.)

- ^ Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 548, 776. ISBN 0-313-30984-1. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

The Romanians are a Latin nation [...] Romance (Latin) nations... Romanians

- ^ Cole, Jeffrey (2011). Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-302-6. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

Romanians are the only Latin people to adopt Orthodoxy

- ^ *"Vlach - History, Language & Culture". britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

Although the origin of Aromanian and Meglenoromanian (and Romanian) from Balkan Latin is beyond question, it is unclear to what extent contemporary Balkan Romance speakers are descended from Roman colonists or from indigenous pre-Roman Balkan populations who shifted to Latin. [...] Nationalist historians deploy one or the other scenario to justify modern territorial claims or claims to indigeneity. Thus, Hungarian (Magyar) claims to Transylvania assume a complete Roman exodus from Dacia, while Romanian claims assume that Romance continued to be spoken by Romanized Dacians. Most scholars who are not nationally affiliated assume the second scenario.

- "Dacia, summary". britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

Dacia, Ancient country, central Europe. Roughly equivalent to modern Romania

- "Dacia, summary". britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ a b Ethnic Groups Worldwide: A Ready Reference Handbook By David Levinson, Published 1998 – Greenwood Publishing Group.

- ^ a b At the time of the 1989 census, Moldova's total population was 4,335,400. The largest nationality in the republic, ethnic Romanians, numbered 2,795,000 persons, accounting for 64.5 percent of the population. Source : U.S. Library of Congress Archived 21 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine: "however it is one interpretation of census data results. The subject of Moldovan vs Romanian ethnicity touches upon the sensitive topic of" Moldova's national identity, page 108 sqq. Archived 6 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rita J. Markel, The Fall of the Roman Empire, p. 17, Twenty-First Century Books, 2007

- ^ Brian W. Jones, The Emperor Domitian, (London: Routledge, 1992), p. 150

- ^ Hind 1984, p. 191: "The emperor Aurelian formed two provinces of Moesia Superior and Inferior. In fact, Dacia Ripensis was formed out of a stretch of the Danube between Moesia Superior and Inferior, while Dacia Mediterranea was the old inland Balkan region of Dardania."

- ^ Jones 1988, p. 231: "When founded as a colony by Trajan, Ratiaria was within Moesia Superior: when Aurelian withdrew from the old Dacia north of the Danube and established a new province of the same name on the south (Dacia Ripensis), Ratiaria became the capital. As such it was the seat of the military governor (dux), and the base of the legion XIII Gemina. It flourished in the fourth and fifth centuries, and according to the historian Priscus was μεγίστη καί πολυάνθρωπος ("very great and with numerous inhabitants") when it was captured by the Huns in the early 440s. It appears to have recovered from this sack, but was finally destroyed by the Avars in 586, though the name survives in the modern Arcar."

- ^ Curta 2006.

- ^ Curta 2001.

- ^ Janković 2004, p. 39–61.

- ^ a b c Kazhdan, Alexander (1991). "Scythia Minor". In Kazhdan, Alexander (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504652-8.

- ^ Rizos, Efthymios (2018). "Scythia Minor". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.

- ^ Wiewiorowski 2008, p. 11.

- ^ Zahariade 2006, p. 236.

- ^ Peoples of Europe. Marshall Cavendish Corporation. 2002. p. 408. ISBN 0-7614-7378-5.

vlachs maramures.

- ^ International Boundary Study Hungary – Romania (Rumania) Boundary (PDF) (Report). Vol. 47. US Office of the Geographer Bureau of Intelligence and Research. 15 April 1965. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- ^ Hammel, E. A. and Kenneth W. Wachter. "The Slavonian Census of 1698. Part I: Structure and Meaning, European Journal of Population". University of California. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- ^ Maria Cvasnîi Cătănescu (1996). Limba română: origini și dezvoltare. Humanitas. p. 64. ISBN 978-973-28-0659-3. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ^ Hitchins 2014, p. 16.

- ^ Bóna, István (2001). "Southern Transylvania under Bulgar Rule". In Köpeczi, Béla; Barta, Gábor; Bóna, István; Makkai, László; Szász, Zoltán; Borus, Judit (eds.). History of Transylvania. Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 0-88033-479-7. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ A. Decei, V. Ciocîltan, "La mention des Roumains (Walah) chez Al-Maqdisi", in Romano-arabica I, Bucharest, 1974, pp. 49–54

- ^ Ibn al Nadim, al-Fihrist. English translation: The Fihrist of al-Nadim. Editor și traducător: B. Dodge, New York, Columbia University Press, 1970, p. 37 with n.82

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 83.

- ^ Annals of Niketas Choniates, Translated by H.J. Magoulias, Wayne State University Press, Detroit, 1984, p.238-371. (https://archive.org/details/o-city-of-byzantium-annals-of-niketas-choniates-ttranslated-by-harry-j-magoulias-1984)

- ^ E. Stănescu, op. cit., pp. 585-588

- ^ V. Mărculeț, Vlachs during the Comnenian period, p. 46.

- ^ John Kinnamos, Epitoma, in Fontes Historiae Daco-Romanae, vol. III, Bucharest, 1975, VI, pp 3.

- ^ Les "Blachoi" de Kinnamos et Choniatès et la présence militaire byzantine au nord du Danube sous les Comnènes. Stanescu, Eugen. (1971) - In: Revue des études sud-est européennes vol. 9 (1971) p. 585-593 http://opac.regesta-imperii.de/lang_en/anzeige.php?pk=337176 Archived 6 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ V. Mărculeț, The Vlachs in the military actions during the Comnen, in Revista de Istorie Militară, 2(60), 2000, p. 46-47 (hereinafter: The Vlachs during the Comnen).

- ^ Kristó, Gyula (2003). Háborúk és hadviselés az Árpádok korában [Wars and Tactics under the Árpáds] (in Hungarian). Szukits Könyvkiadó. ISBN 963-9441-87-2.

- ^ V. Klyuchevsky, The course of the Russian history. v.1: "Myslʹ.1987, ISBN 5-244-00072-1

- ^ "Encyclopædia Britannica: Vlach". Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ Kolarz, Walter (1972). Myths and Realities in Eastern Europe. Kennikat Press. p. 217. ISBN 0-8046-1600-0. Archived from the original on 26 April 2023. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ Bóna 1994, p. 189.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 408.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 407, 414.

- ^ Pop, Ioan-Aurel (1999), p. 44. Romanians and Romania: A Brief History. Boulder. ISBN 978-0-88033-440-2.

- ^ Simon of Kéza (January 1999). Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum [Deeds of the Hungarians]. Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-9116-31-3. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ Madgearu 2005, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Madgearu 2005, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 76.

- ^ Stoica, Vasile (1919). The Roumanian Question: The Roumanians and their Lands. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh Printing Company. p. 18. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ^ "Treaty of Bucharest/Russo-Turkish history [1812]". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 14 February 2023. Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- ^ a b Stoica, Vasile (1919). The Roumanian Question: The Roumanians and their Lands. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh Printing Company. p. 50. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ^ Dr. Ayfer AKTAŞ, Türk Dili, TDK, 9/2007, s. 484–495, Online: turkoloji.cu.edu.tr Archived 9 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "31 august - Ziua Limbii Române". Agerpres (in Romanian). 31 August 2020. Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ Josan, Andreea (31 August 2023). "Depunere de flori, program pentru copii și spectacol muzical: Agenda completă a evenimentelor dedicate Zilei Limbii Române". TV8 (in Romanian). Archived from the original on 1 September 2023. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ^ Romanian language Archived 25 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine on Ethnologue.

- ^ "Explanatory Dictionary of the Romanian Language, 1998; New Explanatory Dictionary of the Romanian Language, 2002" (in Romanian). Dexonline.ro. Archived from the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ Vladimír Baar, Daniel Jakubek, (2017) Divided National Identity in Moldova, Journal of Nationalism, Memory & Language Politics, Volume 11: Issue 1, doi:10.1515/jnmlp-2017-0004.

- ^ Drugaș, Șerban George Paul (2016). "The Wallachians in the Nibelungenlied and their Connection with the Eastern Romance Population in the Early Middle Ages". Hiperboreea. 3 (1): 71–124. doi:10.3406/hiper.2016.910. S2CID 149983312. Archived from the original on 10 August 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ Ioan-Aurel Pop, Italian Authors and the Romanian Identity in the 16th Century, Revue Roumaine d'Histoire, XXXIX, 1-4, p. 39-49, Bucarest, 2000

- ^ "Connubia iunxit cum provincialibus, ut hoc vinculo unam gentem ex duabus faceret, brevi quasi in unum corpus coaluerunt et nunc se Romanos vocant, sed nihil Romani habent praeter linguam et ipsam quidem vehementer depravatam et aliquot barbaricis idiomatibus permixtam." in Magyar Történelmi Tár – 4. sorozat 4. kötet – 1903. - REAL-J Archived 24 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine; also see Endre Veress, Fontes rerum transylvanicarum: Erdélyi történelmi források, Történettudományi Intézet, Magyar Tudományos Akadémia, Budapest, 1914, Vol. IV, S. 204 and also Maria Holban, Călători străini în Țările Române, Editura Științifică, București, 1968, Vol. 1, p. 247 and also in Gábor Almási, I Valacchi visti dagli Italiani e il concetto di Barbaro nel Rinascimento, Storia della Storiografia, 52 (2007): 049-066

- ^ "...si dimandano in lingua loro Romei...se alcuno dimanda se sano parlare in la lingua valacca, dicono a questo in questo modo: Sti Rominest ? Che vol dire: Sai tu Romano,..." and further "però al presente si dimandon Romei, e questo è quanto da essi monacci potessimo esser instruiti" in Claudio Isopescu, Notizie intorno ai Romeni nella letteratura geografica italiana del Cinquecento, in "Bulletin de la Section Historique de l'Académie Roumaine", XIV, 1929, p. 1- 90 and also in Maria Holban, Călători străini în Țările Române, Editura Științifică, București, 1968, Vol. 1, p. 322-323 For the original text also see Magyar Történelmi Tár, 1855, p. 22-23 Archived 19 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Tout ce pays la Wallachie et Moldavie et la plus part de la Transivanie a esté peuplé des colonie romaines du temps de Traian l'empereur...Ceux du pays se disent vrais successeurs des Romains et nomment leur parler romanechte, c'est-à-dire romain ... " cited from "Voyage fait par moy, Pierre Lescalopier l'an 1574 de Venise a Constantinople", fol 48 in Paul Cernovodeanu, Studii si materiale de istorie medievala, IV, 1960, p. 444

- ^ " Valachi, i quali sono i più antichi habitatori ... Anzi essi si chiamano romanesci, e vogliono molti che erano mandati quì quei che erano dannati a cavar metalli..." in Maria Holban, Călători străini despre Țările Române, vol. II, p. 158–161 and also in Gábor Almási, Constructing the Wallach "Other" in the Late Renaissance in Balázs Trencsény, Márton Zászkaliczky (edts), Whose Love of Which Country, Brill, Leiden, Boston 2010, p.127 Archived 5 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine and also in Gábor Almási, I Valacchi visti dagli Italiani e il concetto di Barbaro nel Rinascimento, Storia della Storiografia, 52 (2007): 049-066, p.65

- ^ "Valachi autem hodierni quicunque lingua Valacha loquuntur se ipsos non dicunt Vlahos aut Valachos sed Rumenos et a Romanis ortos gloriantur Romanaque lingua loqui profitentur" in: Johannes Lucii, De Regno Dalmatiae et Croatiae, Amsteldaemi, 1666, pag. 284 Archived 11 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pop, Ioan-Aurel. "On the Significance of Certain Names: Romanian/Wallachian and Romania/Wallachia" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- ^ Rosetti, Alexandru (1986). Editura Științifică și Enciclopedică, București (ed.). Istoria Limbii Române. Vol I (1986). p. 448.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ T. Kamusella, The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe, Springer, 2008, ISBN 978-0-230-58347-4, p. 208; 452.

- ^ In Romanian the ethnonym român, derived from Latin Romanus, had acquired the same meaning as Greek Romaios (in the sense of Orthodox Christian)... Obviously, the Latin Romanus and Greek Romaios shared the same semantic development from an ethnic, or rather, political community to religious denomination. Raymond Detrez on p. 41 in Pre-National Identities in the Balkans in: Entangled Histories of the Balkans - Volume One, pp. 13–65, doi:10.1163/9789004250765_003

- ^ Wolfgang Dahmen, who has questioned the continuity between romanus and român as an ethnic denomination, notes: One might also suppose that the early identification of ROMANUS with "Christian" (as opposed to PAGANUS, which then acquired also the meaning of "non-Roman"), has contributed to the preservation of the former meaning. Dahmen, Wolfgang, "Pro- und antiwestliche Strömungen im rumänischen literarischen Diskurs – ein Überblick," in Gabriella Schubert and Holm Sundhaussen (eds.): Prowestliche und antiwestliche Diskurse in den Balkanländern / Südosteuropa. 43. Internationale Hochschulwoche der Südosteuropa-Gesellschaft in Tutzing 4. - 8.10.2004, München 2008, 59-75. as cited by Raymond Detrez on p. 41 in Pre-National Identities in the Balkans in: Entangled Histories of the Balkans Archived 2 August 2023 at the Wayback Machine - Volume One, pp. 13–65, doi:10.1163/9789004250765_003

- ^ "Definition of the term 'daco-roman'". Dex.ro (in Romanian). Archived from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ "Definition of the term 'dacoromân'". Dex.ro (in Romanian). Archived from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ a b c In an ever more globalized world the incredibly diverse and widespread phenomenon of migration has played a significant role in the ways in which notions such as "home," "membership" or "national belonging" have constantly been disputed and negotiated in both sending and receiving societies. – Rogers Brubaker, Citizenship and Nationhood (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994).

- ^ "2000 U.S. Census, ancestry responses". US Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 10 February 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "Migration Information Source". migrationpolicy.org. Archived from the original on 17 February 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ^ Oršolić, Marijan (17 February 2016). "Život u sjeni konstitutivnih naroda – Rumunji u BiH". Prometej (in Bosnian). Archived from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- ^ Marian, Mircea (11 April 2015). "IRES: Aproape 9 din 10 români se consideră religioși, dar doar 10% țin post". Evenimentul Zilei (in Romanian). Archived from the original on 14 April 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ "Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 10 May 2017. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ "Orthodox Christianity in the 21st Century". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 10 November 2017. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ "Populaţia rezidentă după etnie şi religie (Etnii, Religii, Județe, Medii de rezidență)". Institutul Național de Statistică (in Romanian). Archived from the original on 13 November 2024. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ "National Report: Romania – Autumn 2006" (PDF) (in Romanian). European Commission, Eurobarometer. 2006. p. 25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2007.

- ^ "Barometrul de Opinie Publică" [Barometer of Public Opinion] (PDF). Open Society Foundations. May 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ Jones, Arnold Hugh Martin (1978) [1948]. Constantine and the Conversion of Europe (1962 ed.). University of Toronto Press (reprint 2003) [Macmillan: Teach Yourself History, 1948, Medieval Academy of America: Reprint for Teaching, 1978]. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-8020-6369-4. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ Bogdan Banu. "Istro-Romanians in Croatia". Istro-romanian.net. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "Romanian Y-DNA haplogroups". Google Docs. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ Karachanak et al., 2012. Karachanak, S., V. Carossa, D. Nesheva, A. Olivieri, M. Pala, B. Hooshiar Kashani, V. Grugni, et al. "Bulgarians vs the Other European Populations: A Mitochondrial DNA Perspective." International Journal of Legal Medicine 126 (2012): 497.

- ^ Modi, Alessandra; Nesheva, Desislava; Sarno, Stefania; Vai, Stefania; Karachanak-Yankova, Sena; Luiselli, Donata; Pilli, Elena; Lari, Martina; Vergata, Chiara; Yordanov, Yordan; Dimitrova, Diana; Kalcev, Petar; Staneva, Rada; Antonova, Olga; Hadjidekova, Savina; Galabov, Angel; Toncheva, Draga; Caramelli, David (December 2019). "Ancient human mitochondrial genomes from Bronze Age Bulgaria: new insights into the genetic history of Thracians". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 5412. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.5412M. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-41945-0. PMC 6443937. PMID 30931994.

- ^ Bosch2006, Varzari2006, Varzari 2013, Martinez-Cruz 2012

- ^ a b Martinez-Cruz B, Ioana M, Calafell F, Arauna LR, Sanz P, Ionescu R, Boengiu S, Kalaydjieva L, Pamjav H, Makukh H, Plantinga T, van der Meer JW, Comas D, Netea MG (2012). Kivisild T (ed.). "Y-chromosome analysis in individuals bearing the Basarab name of the first dynasty of Wallachian kings". PLOS ONE. 7 (7) e41803. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...741803M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041803. PMC 3404992. PMID 22848614.

- ^ Rootsi, Siiri (2004). Human Y-chromosomal variation in European populations (PhD Thesis). Tartu University Press. hdl:10062/1252

- ^ Marjanovic D, Fornarino S, Montagna S, Primorac D, Hadziselimovic R, Vidovic S, et al. (November 2005). "The peopling of modern Bosnia-Herzegovina: Y-chromosome haplogroups in the three main ethnic groups". Annals of Human Genetics. 69 (Pt 6): 757–763. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00190.x. PMID 16266413. S2CID 36632274.

- ^ Rębała K, Mikulich AI, Tsybovsky IS, Siváková D, Džupinková Z, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A, Szczerkowska Z (16 March 2007). "Y-STR variation among Slavs: evidence for the Slavic homeland in the middle Dnieper basin". Journal of Human Genetics. 52 (5): 406–414. doi:10.1007/s10038-007-0125-6. PMID 17364156.

- ^ Zupan A, Vrabec K, Glavač D (2013). "The paternal perspective of the Slovenian population and its relationship with other populations". Annals of Human Biology. 40 (6): 515–526. doi:10.3109/03014460.2013.813584. PMID 23879710. S2CID 34621779.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Fóthiwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Pamjav H, Fehér T, Németh E, Koppány Csáji L (2019). Genetika és őstörténet (in Hungarian). Napkút Kiadó. p. 58. ISBN 978-963-263-855-3.

Az I2-CTS10228 (köznevén "dinári-kárpáti") alcsoport legkorábbi közös őse 2200 évvel ezelőttre tehető, így esetében nem arról van szó, hogy a mezolit népesség Kelet-Európában ilyen mértékben fennmaradt volna, hanem arról, hogy egy, a mezolit csoportoktól származó szűk család az európai vaskorban sikeresen integrálódott egy olyan társadalomba, amely hamarosan erőteljes demográfiai expanzióba kezdett. Ez is mutatja, hogy nem feltétlenül népek, mintsem családok sikerével, nemzetségek elterjedésével is számolnunk kell, és ezt a jelenlegi etnikai identitással összefüggésbe hozni lehetetlen. A csoport elterjedése alapján valószínűsíthető, hogy a szláv népek migrációjában vett részt, így válva az R1a-t követően a második legdominánsabb csoporttá a mai Kelet-Európában. Nyugat-Európából viszont teljes mértékben hiányzik, kivéve a kora középkorban szláv nyelvet beszélő keletnémet területeket.

- ^ Olalde, Iñigo; Carrión, Pablo (7 December 2023). "A genetic history of the Balkans from Roman frontier to Slavic migrations". Cell. 186 (25): P5472–5485.E9. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2023.10.018. PMC 10752003. PMID 38065079.